Abstract

Background and purpose:

While combination aspirin and clopidogrel reduces recurrent stroke compared to aspirin alone in patients with TIA or minor stroke, the effect on disability is uncertain.

Methods:

The POINT trial randomized patients with TIA or minor stroke (NIHSS≤3) within 12 hours of onset to dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin plus clopidogrel versus aspirin alone. The primary outcome measure was a composite of stroke, MI, or vascular death. We performed a post-hoc exploratory analysis to examine the effect of treatment on overall disability (defined as mRS>1) at 90 days as well as disability ascribed by the local investigator to index or recurrent stroke. We also evaluated predictors of disability.

Results:

At 90 days, 188/1964 (9.6%) of patients enrolled with TIA and 471/2586 (18.2%) of those enrolled with stroke were disabled. Overall disability was similar between patients assigned DAPT versus aspirin alone (14.7% vs. 14.3%, OR 0.97, 95%CI 0.82–1.14, p=0.69). However, there were numerically fewer patients with disability in conjunction with a primary outcome event in the DAPT arm (3.0% vs. 4.0%, OR 0.73, 95%CI 0.53–1.01, p=0.06), and significantly fewer patients in the DAPT arm with disability attributed by the investigators to either the index event or recurrent stroke (5.9% vs. 7.4%, OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.99, p=0.04). Notably, disability attributed to the index event accounted for the majority of this difference (4.5% vs. 6.0%, OR 0.74 95% CI 0.57–0.96, p=0.02). In multivariate analysis, age, subsequent ischemic stroke, serious adverse events, and major bleeding were significantly associated with disability in TIA; for those with stroke, female sex, hypertension or diabetes, NIHSS score, recurrent ischemic stroke, subsequent myocardial infarction, and serious adverse events were associated with disability.

Conclusions:

In addition to reducing recurrent stroke in patients with acute minor stroke and TIA, dual antiplatelet therapy might reduce stroke-related disability.

Clinical Trial Registration:

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00991029.

Keywords: transient ischemic attack, minor stroke, disability

Subject terms: transient ischemic attack, ischemic stroke

Introduction:

Early treatment of transient ischemic attack (TIA) and minor stroke with aspirin reduces both the risk and severity of recurrent stroke.(1) Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel in this population further reduces the risk of recurrent stroke beyond aspirin alone.(2, 3) However, the impact of this treatment on subsequent functional disability and stroke severity has received less attention. Recurrent stroke is a major contributor to disability following TIA and minor stroke, and thus a treatment that reduces this risk would be expected to also reduce the risk of disability. (4, 5) However, many other factors also contribute to disability following TIA and minor stroke, such as bleeding events, medical complications, and, in the case of minor stroke, the initial deficits from the index stroke. We sought to examine factors associated with disability in the POINT trial, including the effect of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Methods:

Data availability

The authors will make the data, detailed methods, and all other study materials available to researchers who wish to reproduce the analysis in this manuscript.

Study design and patients

The Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) Trial was a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial which enrolled patients with minor stroke (National Institute of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (Age, Blood pressure, Clinical features, Duration, Diabetes [ABCD2] score ≥ 4) within 12 hours of symptom onset. A diagnosis of TIA was assigned if there was complete resolution of symptoms and absence of acute infarction on initial imaging completed at the time of randomization, regardless of the results of subsequent imaging. Full details of the trial have been published previously.(3) Briefly, eligible patients were randomized to clopidogrel (given orally as a 600 mg load followed by 75 mg daily) versus placebo, with all patients receiving aspirin. The recommended aspirin dose was 162 mg daily for 5 days followed by 81 mg daily, though the exact dose of aspirin was at the discretion of the treating physician. Patients were followed for 90 days. Patients with a known cardiac source of embolism or with a carotid stenosis for which revascularization was anticipated were excluded. The present analysis included all patients enrolled in POINT, regardless of baseline disability status, which was not collected. The study was approved by the relevant ethics committee at each enrolling site, and all participants provided written informed consent. The POINT trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00991029).

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure for the POINT trial was the composite of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic vascular causes. The primary safety outcome measure was major hemorrhage, defined as symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, intraocular bleeding causing vision loss, transfusion of ≥2 units of red cells or an equivalent amount of whole blood, or hospitalization, prolongation of an existing hospitalization, or death due to hemorrhage. Operationally, investigators were instructed to classify both new neurologic deficits and any worsening of pre-existing deficits ascribed to cerebral ischemia as recurrent stroke. For the present post-hoc exploratory analysis the primary outcome measure was disability, defined as a modified Rankin scale (mRS) >1 at 90 days or the last available follow-up if the 90 day mRS was not collected. This was assessed at an in-person clinic visit, or if not available, by telephone interview. Patients with neither a 90 day mRS nor one to be carried forward were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

In patients with disability, investigators were asked at the final study visit to attribute the disability to either the index stroke, subsequent stroke, both, or other cause. As the causal pathway between treatment assignment (aspirin + clopidogrel vs. aspirin alone) and disability would be expected to be mediated primarily by ischemic outcome events, we analyzed the difference between treatment groups in 90-day disability associated with 1) a primary study endpoint (stroke, myocardial infarction, vascular death) and 2) based on investigator attribution of disability to the index or subsequent cerebrovascular event. We also analyzed disability associated with major hemorrhage. For analysis of factors associated with disability, initial univariate analysis compared baseline factors between those disabled at 90 days compared to those without disability, analyzing patients enrolled with stroke and TIA separately. Selection of baseline factors for inclusion paralleled those reported in the primary POINT trial analysis. Multivariable analysis of factors associated with disability was performed using logistic regression. Age, baseline NIHSS, recurrent ischemic stroke, MI, and factors significant at p<0.01 in univariate analysis were included in the model for patients enrolled with stroke; age, recurrent ischemic stroke, MI, and factors significant at p<0.01 in univariate analysis were included in the model for patient enrolled with TIA. A threshold of p<0.01 for inclusion of variable from the univariate analysis was chosen to avoid overfitting of the model given the sample size and number of variables. Additionally, to determine the association between baseline characteristics and disability independent of subsequent recurrent ischemic events, a similar analysis was repeated excluding patients with subsequent ischemic stroke or MI. The analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4.

Results:

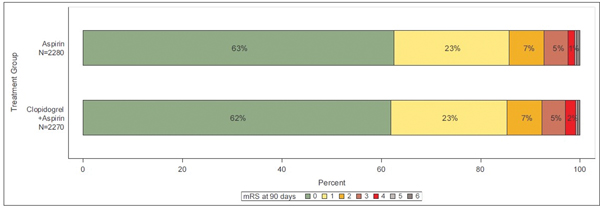

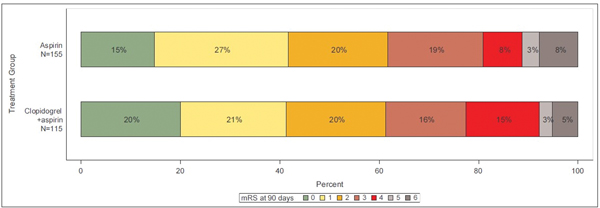

Of the 4,881 patients enrolled in the POINT trial, 331 were excluded due to lack of an available follow-up mRS score, leaving 4550 patients, of which 2586 were enrolled with stroke and 1964 with TIA. Missing mRS scores at 90 days were imputed with the mRS score observed at the outcome event visit for 24 (0.5%) patients. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. At 90 days, 188/1964 (9.6%) of patients enrolled with TIA and 471/2586 (18.2%) of those enrolled with stroke were disabled. Distribution of mRS scores in the overall cohort and in those with a primary outcome endpoint are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Stroke (N=2586) |

TIA (N=1964) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (interquartile range) | 63 (55–73) | 66.5 (57–76) |

| Female sex – no. (%) | 1107 (43%) | 923 (47%) |

| Race | ||

| Asian - no. (%) | 81 (3%) | 54 (3%) |

| Black/African American - no.(%) | 511 (20%) | 367 (19%) |

| White - no. (%) | 1878 (73%) | 1471 (75%) |

| Other - no. (%) | 116 (4%) | 272(4%) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino | 157 (6%) | 108 (5%) |

| History of ischemic heart disease, no. (%) | 235 (9%) | 228 (12%) |

| History of hypertension, no. (%) | 1760 (68%) | 1398 (71%) |

| History of diabetes mellitus, no. (%) | 682 (26%) | 561 (29%) |

| Qualifying TIA baseline ABCD2 score | ||

| ≤ 5 - no. (%) | - | 1452 (74%) |

| 6–7 – no. (%) | - | 509 (26%) |

| Qualifying ischemic stroke baseline NIHSS | ||

| 0–1 - no.(%) | 1214 (47%) | - |

| 2–3 - no.(%) | 1343 (52%) | - |

Figure 1a.

Distribution of modified Rankin scores at 90 days in entire cohort

In the analyzed population, new ischemic stroke occurred in 257 (5.6%) patients, MI in 16 (0.4%), major bleeding in 33 (0.7%) and other serious adverse events in 523 (11.5%). Of the stroke patients who ended up disabled, 39% experienced one of these post-randomization events. For patients enrolled with TIA, 52% of the patients who ended up disabled experienced one of these post-randomization events. Disability rates associated with specific patient characteristics and subsequent vascular events are shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Rate of disability (mRS>1) by patient characteristics and outcome events

| Index event: Stroke N=2,586 | Index event: TIA N=1,964 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not disabled(mRS 0–1) | Disabled(mRS 2–6) | Not disabled(mRS 0–1) | Disabled(mRS 2–6) | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | Subgroup Total | N | % | N | % | Subgroup Total | |

| All | 2115 | 81.8% | 471 | 18.2% | 2,586 | 1776 | 90.4% | 188 | 9.6% | 1,964 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <65 years | 1154 | 84.4% | 213 | 15.6% | 1367 | 818 | 94.0% | 52 | 6.0% | 870 |

| >=65 years | 961 | 78.8% | 258 | 21.2% | 1219 | 958 | 87.6% | 136 | 12.4% | 1094 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 1238 | 83.7% | 241 | 16.3% | 1479 | 954 | 91.6% | 87 | 8.4% | 1041 |

| Female | 877 | 79.2% | 230 | 20.8% | 1107 | 822 | 89.1% | 101 | 10.9% | 923 |

| Race | ||||||||||

| Asian | 62 | 76.5% | 19 | 23.5% | 81 | 49 | 90.7% | 5 | 9.3% | 54 |

| Black | 387 | 75.7% | 124 | 24.3% | 511 | 322 | 87.7% | 45 | 12.3% | 367 |

| Other/Unknown | 99 | 85.3% | 17 | 14.7% | 116 | 68 | 94.4% | 4 | 5.6% | 72 |

| White | 1567 | 83.4% | 311 | 16.6% | 1878 | 1337 | 90.9% | 134 | 9.1% | 1471 |

| US, Hispanic | ||||||||||

| No | 1996 | 82.2% | 433 | 17.8% | 2429 | 1680 | 90.5% | 176 | 9.5% | 1856 |

| Yes | 119 | 75.8% | 38 | 24.2% | 157 | 96 | 88.9% | 12 | 11.1% | 108 |

| History of ischemic heart disease | ||||||||||

| No | 1922 | 82.0% | 421 | 18.0% | 2343 | 1578 | 91.1% | 154 | 8.9% | 1732 |

| Yes | 185 | 78.7% | 50 | 21.3% | 235 | 195 | 85.5% | 33 | 14.5% | 228 |

| History of hypertension | ||||||||||

| No | 729 | 89.0% | 90 | 11.0% | 819 | 527 | 95.1% | 27 | 4.9% | 554 |

| Yes | 1380 | 78.4% | 380 | 21.6% | 1760 | 1239 | 88.6% | 159 | 11.4% | 1398 |

| History of diabetes mellitus | ||||||||||

| No | 1596 | 84.1% | 301 | 15.9% | 1897 | 1284 | 91.6% | 118 | 8.4% | 1402 |

| Yes | 513 | 75.2% | 169 | 24.8% | 682 | 491 | 87.5% | 70 | 12.5% | 561 |

| Baseline ABCD2 score | ||||||||||

| 4–5 | 1332 | 91.7% | 120 | 8.3% | 1452 | |||||

| >5 | 441 | 86.6% | 68 | 13.4% | 509 | |||||

| Baseline NIHSS score | ||||||||||

| 0–1 | 1074 | 88.5% | 140 | 11.5% | 1214 | |||||

| 2–3 | 1019 | 75.9% | 324 | 24.1% | 1343 | |||||

| >3 | 22 | 75.9% | 7 | 24.1% | 29 | |||||

| Ischemic stroke (Post-randomization) | ||||||||||

| No | 2049 | 84.8% | 367 | 15.2% | 2416 | 1736 | 92.5% | 141 | 7.5% | 1877 |

| Yes | 66 | 38.8% | 104 | 61.2% | 170 | 40 | 46.0% | 47 | 54.0% | 87 |

| Myocardial infarction (Post-randomization) | ||||||||||

| No | 2112 | 82.0% | 463 | 18.0% | 2575 | 1773 | 90.5% | 186 | 9.5% | 1959 |

| Yes | 3 | 27.3% | 8 | 72.7% | 11 | 3 | 60.0% | 2 | 40.0% | 5 |

| Other SAEs (excluding primary efficacy and safety events) | ||||||||||

| No | 1907 | 83.5% | 378 | 16.5% | 2285 | 1613 | 92.6% | 129 | 7.4% | 1742 |

| Yes | 208 | 69.1% | 93 | 30.9% | 301 | 163 | 73.4% | 59 | 26.6% | 222 |

| Major Hemorrhage (Post-randomization) | ||||||||||

| No | 2106 | 81.9% | 464 | 18.1% | 2570 | 1767 | 90.8% | 180 | 9.2% | 1947 |

| Yes | 9 | 56.3% | 7 | 43.8% | 16 | 9 | 52.9% | 8 | 47.1% | 17 |

| Any post-randomization event event* | ||||||||||

| No | 1837 | 86.4% | 289 | 13.6% | 2126 | 1573 | 94.5% | 91 | 5.5% | 1664 |

| Yes | 278 | 60.4% | 182 | 39.6% | 460 | 203 | 67.7% | 97 | 32.3% | 300 |

Note: For counts of post-randomization events, patients with more than one type of event were only counted once.

Investigator attribution of disability was missing in 252/659 (38%) disabled patients. In the 407 patients for which it was available, disability was ascribed to index stroke in 233 (57%), recurrent stroke in 64 (16%), and other cause in 104 (26%); in 6 (1%) patients both index and recurrent stroke were indicated as related to disabling outcome.

Table 3 shows the effect of treatment assignment on disability. In the overall cohort, there was no significant difference in disability at 90 days between patients assigned clopidogrel + aspirin compared to aspirin alone (14.3% vs. 14.7%, OR 0.97, 95%CI 0.82–1.14, p=0.69). There were numerically fewer patients with disability in conjunction with a primary outcome event in the dual antiplatelet arm (3.0% vs. 4.0%, OR 0.73, 95%CI 0.53–1.01, p=0.06). This difference favoring dual antiplatelet therapy was seen in patients enrolled with minor stroke as the index event (3.4% vs. 5.2%, OR 0.63, 95%CI 0.43–0.93, p=0.02) but not in patients enrolled with TIA (2.4% vs. 2.4%, OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.58–1.84, p=0.92). Additionally, there were significantly fewer patients in the dual antiplatelet arm with disability attributed by the investigator to either the index event or recurrent stroke (5.9% vs. 7.4%, OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.99, p=0.04). Notably, disability attributed to the index event accounted for the majority of this difference (4.5% vs. 6.0%, OR 0.74 95% CI 0.57–0.96, p=0.02). There was no significant difference in disability associated with major hemorrhage between patients assigned dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin alone. Supplememental Table I shows exploratory analysis using an alternative definition of disability (mRS>2); supplemental Tables II and III show an exploratory analysis in younger (age<65) compared to older (age≥65) patients.

Table 3:

Effect of treatment assignment on disability (mRS>1) at 90 days

| Outcome | Clopidogrel + aspirin | Aspirin | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | N=2270 | N= 2280 | ||

| Disability in overall population | 324 (14.3%) | 335 (14.7%) | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 0.69 |

| Disability AND primary outcome endpoint (stroke, MI, vascular death) | 67 (3.0%) | 91 (4.0%) | 0.73 (0.53–1.01) | 0.06 |

| Disability AND major hemorrhage | 10 (0.4%) | 5 (0.2%) | 2.01 (0.69–5.90) | 0.19 |

| Disability attributed to recurrent stroke per local investigator | 33 (1.5%) | 37 (1.6%) | 0.89 (0.56–1.44) | 0.64 |

| Disability attributed to index stroke per local investigator | 102 (4.5%) | 137 (6.0%) | 0.74 (0.57–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Disability attributed to either recurrent or index stroke per local investigator | 134 (5.9%) | 169 (7.4%) | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.04 |

| Patients enrolled with index stroke | N=1281 | N=1305 | ||

| Disability in overall population | 221 (17.3%) | 250 (19.2%) | 0.88 (0.72–1.07) | 0.21 |

| Disability AND primary outcome endpoint (stroke, MI, vascular death) | 43 (3.4%) | 68 (5.2%) | 0.63 (0.43–0.93) | 0.02 |

| Disability AND major hemorrhage | 4 (0.3%) | 3 (0.2%) | 1.36 (0.30–6.09) | 0.69 |

| Disability attributed to recurrent stroke per local investigator | 16 (1.3%) | 20 (1.5%) | 0.81 (0.42–1.58) | 0.54 |

| Disability attributed to index stroke per local investigator | 91 (7.1%) | 128 (9.8%) | 0.70 (0.53–0.93) | 0.01 |

| Disability attributed to either recurrent or index stroke per local investigator | 107 (8.4%) | 144 (11.0%) | 0.73 (0.56–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Patients enrolled with TIA | N=989 | N=975 | ||

| Disability in overall population | 103 (10.4%) | 85 (8.7%) | 1.22 (0.90–1.65) | 0.20 |

| Disability AND primary outcome endpoint (stroke, MI, vascular death) | 24 (2.4%) | 23 (2.4%) | 1.03 (0.58–1.84) | 0.92 |

| Disability AND major hemorrhage | 6 (0.6%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2.97 (0.60–14.75) | 0.16 |

| Disability attributed to either recurrent stroke or index event per local investigator | 27 (2.7%) | 25 (2.6%) | 1.07 (0.61–1.85) | 0.82 |

Univariate analysis of factors associated with disability is shown in Table 4, and multivariate analysis in Table 5. Factors significantly associated with disability in TIA patients in multivariate analysis were age, subsequent ischemic stroke, serious adverse events, and major bleeding; for stroke patients, factors were female sex, history of hypertension or diabetes, higher NIHSS score, recurrent ischemic stroke, subsequent myocardial infarction, and serious adverse events.

Table 4:

Univariate analysis of risk factors for disability (mRS>1)

| Characteristic | StrokeOR (95% CI) | p-value | TIAOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | N=2,586 | N=1,964 | ||

| Age ≥ 65 (<65 is reference) | 1.45 (1.19–1.78) | <.001 | 2.23 (1.60–3.12) | <.001 |

| Female (Male is reference) | 1.35 (1.10–1.65) | <.01 | 1.35 (1.00–1.82) | 0.05 |

| Race | <.001 | 0.20 | ||

| Asian vs White | 1.54 (0.91–2.62) | 1.02 (0.40–2.60) | ||

| Black vs White | 1.61 (1.28–2.04) | 1.39 (0.97–2.00) | ||

| Other vs White | 0.87 (0.51–1.47) | 0.59 (0.21–1.63) | ||

| US, Hispanic or Latino | 1.47 (1.01–2.15) | 0.05 | 1.19 (0.64–2.22) | 0.58 |

| History of ischemic heart disease | 1.23 (0.89–1.72) | 0.21 | 1.73 (1.16–2.60) | <.01 |

| History of hypertension | 2.23 (1.74–2.85) | <.001 | 2.50 (1.64–3.81) | <.001 |

| History of diabetes | 1.75 (1.41–2.16) | <.001 | 1.55 (1.13–2.12) | <.01 |

| Baseline ABCD2 score >5 vs ≤5(TIA only) | -- | -- | 1.71 (1.25–2.35) | <.001 |

| Baseline NIHSS score 2–3 vs. 0–1 (Stroke only) | 2.44 (1.97–3.03) | <.001 | -- | -- |

| Ischemic stroke (post-randomization) | 8.80 (6.34–12.2) | <.001 | 14.5 (9.18–22.8) | <.001 |

| MI (post-randomization) | 12.2 (3.21–46.0) | <.001 | 6.36 (1.06–38.3) | 0.04 |

| SAE (post-randomization) | 2.26 (1.72–2.95) | <.001 | 4.53 (3.20–6.41) | <.001 |

| Major bleeding (post-randomization) | 3.53 (1.31–9.53) | 0.01 | 8.72 (3.32–22.9) | <.001 |

| Any post-randomization event (Ischemic stroke, MI, major bleeding, or SAE) | 4.16 (3.33–5.21) | <.001 | 8.26 (5.99–11.4) | <.001 |

Table 5:

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with disability

| Index event | Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIA | Age, per year | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <.001 |

| History of ischemic heart disease | 1.15 (0.72–1.84) | 0.55 | |

| History of hypertension | 1.48 (0.93–2.35) | 0.09 | |

| History of diabetes | 1.24 (0.84–1.83) | 0.29 | |

| Baseline ABCD2 score >5 vs ≤5 | 1.21 (0.82–1.77) | 0.33 | |

| Ischemic stroke (post-randomization) | 14.5 (8.70–24.2) | <.001 | |

| MI (post-randomization) | 1.74 (0.08–38.8) | 0.72 | |

| SAE (post-randomization) | 3.62 (2.45–5.34) | <.001 | |

| Major bleeding (post-randomization) | 5.70 (1.97–16.5) | <.01 | |

| EXCLUDING PATIENTS WITH SUBSEQUENT ISCHEMIC STROKE/MI: | |||

| Age, per year | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | <.001 | |

| History of ischemic heart disease | 1.36 (0.84–2.21) | 0.21 | |

| History of hypertension | 1.37 (0.84–2.23) | 0.21 | |

| History of diabetes | 1.24 (0.80–1.92) | 0.33 | |

| Baseline ABCD2 score >5 vs ≤5 | 1.05 (0.69–1.61) | 0.82 | |

| SAE (post-randomization) | 4.53 (3.01–6.82) | <.001 | |

| Major bleeding (post-randomization) | 5.54 (1.88–16.3) | <.01 | |

| Stroke | Age, per year | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.40 |

| Female vs Male | 1.37 (1.10–1.71) | <.01 | |

| Asian vs White | 1.51 (0.85–2.68) | 0.16 | |

| Black vs White | 1.16 (0.89–1.51) | 0.28 | |

| Other Race vs White | 0.79 (0.45–1.39) | 0.41 | |

| History of hypertension | 1.87 (1.42–2.44) | <.001 | |

| History of diabetes | 1.40 (1.10–1.78) | <.01 | |

| Baseline NIHSS score 2–3 vs 0–1 | 2.46 (1.95–3.10) | <.001 | |

| Ischemic stroke (post-randomization) | 8.49 (5.97–12.1) | <.001 | |

| MI (post-randomization) | 5.07 (1.06–24.2) | 0.04 | |

| SAE (post-randomization) | 2.24 (1.66–3.02) | <.001 | |

| Major bleeding (post-randomization) | 2.12 (0.67–6.75) | 0.20 | |

| EXCLUDING PATIENTS WITH SUBSEQUENT ISCHEMIC STROKE/MI: | |||

| Age, per year | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.43 | |

| Female vs Male | 1.33 (1.05–1.68) | 0.02 | |

| Asian vs White | 1.42 (0.78–2.57) | 0.25 | |

| Black vs White | 1.09 (0.82–1.45) | 0.56 | |

| Other Race vs White | 0.79 (0.44–1.44) | 0.45 | |

| History of hypertension | 1.83 (1.37–2.44) | <.001 | |

| History of diabetes | 1.43 (1.11–1.85) | <.01 | |

| Baseline NIHSS score 2–3 vs 0–1 | 2.65 (2.06–3.41) | <.001 | |

| SAE (post-randomization) | 2.31 (1.69–3.15) | <.001 | |

| Major bleeding (post-randomization) | 1.16 (0.24–5.56) | 0.85 | |

MI=myocardial infarction; NIHSS=National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SAE=serious adverse event

Discussion:

Our results indicate that subsequent events, including new or recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, bleeding, and medical complications, are important contributors to disability following TIA and minor stroke. These results are largely consistent with prior data from the SOCRATES trial and the CATCH study, both of which included patients with acute minor stroke or TIA. (4, 5) For instance, in SOCRATES 19% of patients enrolled with minor stroke were disabled at 90 days; of these disabled patients, 39% had a post-randomization event. In POINT, 18% of those with minor stroke were disabled, with an identical 39% having a post-randomization event. For patient enrolled with TIA in SOCRATES, 5% were disabled, 65% of whom had a post-randomization event; in POINT 10% were disabled, 52% of whom had a post-randomization event. Notably, the SOCRATES study included patients with NIHSS scores up to 5 (compared to 3 in POINT), which might have been expected to result in a higher rate of disability; however, patients with baseline disability (mRS > 0) were excluded from the SOCRATES analysis.(6) This fact may also account for the higher rate of disability in TIA patients in POINT compared to SOCRATES. The CATCH study, an observational study of 499 patients with minor stroke and TIA, found that 15% of subjects were disabled at 90 days, 26% of whom had a recurrent neurologic event. (5) In CATCH, minor stroke and TIA patients were pooled together, only subsequent neurologic events were captured, and patients with pre-existing disability were excluded; these factors may account for the differences seen compared to the data from POINT and SOCRATES.

We found that dual antiplatelet therapy was associated with a reduction in disability attributed to the index or recurrent stroke by the local investigator. This reduction was largely driven by a reduction in disability ascribed to the index stroke, and was seen only in patients enrolled with minor stroke and not in those with TIA. This finding suggests the possibility of an additional benefit to dual antiplatelet therapy not captured in the primary outcome event (recurrent stroke, MI, vascular death) used in POINT. Despite the POINT protocol clearly indicating that clinically apparent neurologic deterioration felt to be due to ischemia should be classified as recurrent stroke, it is possible this was not universally recognized by local investigators, particularly in patients with deficits from the index event, which could have led to a failure to completely capture new cerebral ischemic events in the main outcome measure. Alternatively, neurologic progression in the acute period from the index stroke might not have been apparent on bedside neurologic examination, but might have been recognized as a significant functional limitation when the patient attempted to return to more usual activities. Prior work has indeed suggested that mild cognitive and functional deficits are not completely captured by the standard bedside neurologic examination or NIH stroke scale.(7)

Aside from recurrent events, other factors were also independently associated with disability. Perhaps the most notable is the NIHSS score, which was strongly associated with disability in the patients enrolled with minor stroke even within the very narrow range of scores (i.e. NIHSS 0–3) eligible for enrollment in POINT. Of patients with NIHSS scores of 2–3, 24% were disabled at 90 days, compared to 11.5% of those with scores of 0–1. In patients enrolled with minor stroke, but not those with TIA, women appeared to have a greater likelhood of being disabled than men. Previous data from the Framingham study also showed greater post-stroke disability in women, and this was seen in the CATCH study as well. (5, 8) However, it should be noted that we did not exclude patients with pre-morbid disability from our analysis, and prior research has demonstrated that women are more likely to have pre-morbid handicap which may account for differences in observed functional outcomes following stroke.(9) Indeed, no association between sex and disability was seen in an analysis of the SOCRATES trial which did exclude patients with pre-morbid disability. (4)

Several important limitations of this analysis should be noted. First, baseline mRS was not recorded, nor were patients excluded from enrollment on the basis of pre-existing disability. Given randomization, this should not have impacted the comparison of the relative effect of treatment assignment on disability, though it may have affected the observed absolute rates of disability and raises the possibility of confounding in the analysis of the association between other factors and disability. Second, investigator attribution of disability to index or recurrent stroke, as opposed to other causes, was missing in a significant number of subjects and in those in which it was collected may be imperfect. Specifically related to this is the difficulty in distinguishing between disability due to the index event as opposed to recurrent cerebrovascular events. Third, our analysis did not analyze the differential impact of treatment assignment on the risk of disability related to major hemorrhage. However, the rate of major hemorrhage in POINT was very low so it is unlikely this would have had a major effect on our findings.

In conclusion, our data suggest that the benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy, particularly in patients with acute minor stroke, might extend beyond that captured in the primary outcome endpoint of the POINT trial. Thrombus formation and lysis at the site of a vascular occlusion is a dynamic process; combination antiplatelet therapy might shift this balance towards clot dissolution, or might maintain patency of collateral pathways, thus altering progression of the initial ischemic event. This effect may be separate from preventing true de novo recurrent events, and difficult to recognize clinically since ischemia progression may appear as a natural evolution of the initial ischemic injury. Future studies of antithrombotic therapy to improve outcome after minor stroke and TIA might explore using more sensitive measures of disability and targeting patients at highest risk of early progression of ischemia.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1b.

Distribution of modified Rankin scores at 90 days in those with a primary outcome event

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: This trial was supported by grants from the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health (NIH/NINDS U01 NS062835, U01 NS056975, U01 NS059041). The sponsor had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, or presentation of the study. Sanofi provided drug and placebo for 75% of patients in the trial.

Disclosures:

SC Johnston has received grant support from Sanofi and AstraZeneca, non-financial support from Sanofi, and his institution has received research support from AstraZeneca.

References:

- 1.Rothwell PM, Algra A, Chen Z, Diener HC, Norrving B, Mehta Z. Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;388:365–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, Barsan W, Conwit RA, Elm JJ, et al. Clopidogrel and Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke and High-Risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cucchiara B GD, Kasner SE, Knutsson M, Denison H, Ladenvall P, Amarenco P, Johnston SC. Disability after minor stroke and TIA: a secondary analysis of the SOCRATES trial. Neurology. 2019;93:e708-e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coutts SB, Modi J, Patel SK, Aram H, Demchuk AM, Goyal M, et al. What Causes Disability After Transient Ischemic Attack and Minor Stroke? Results From the CT And MRI in the Triage of TIA and minor Cerebrovascular Events to Identify High Risk Patients (CATCH) Study. Stroke. 2012;43:3018–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, Easton JD, Evans SR, et al. Ticagrelor versus Aspirin in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kauranen T, Laari S, Turunen K, Mustanoja S, Baumann P, Poutiainen E. The cognitive burden of stroke emerges even with an intact NIH Stroke Scale Score: a cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:295–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrea RE, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, Kelly-Hayes M, Kase CS, Wolf PA. Gender Differences in Stroke Incidence and Poststroke Disability in the Framingham Heart Study. Stroke. 2009;40:1032–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renoux C, Coulombe J, Li L, Ganesh A, Silver L, Rothwell PM, et al. Confounding by Pre-Morbid Functional Status in Studies of Apparent Sex Differences in Severity and Outcome of Stroke. Stroke. 2017;48:2731–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the data, detailed methods, and all other study materials available to researchers who wish to reproduce the analysis in this manuscript.