Abstract

Visualizing fine neuronal structures deep inside strong light-scattering brain tissue remains a challenge in neuroscience. Recent nanoscopy techniques have reached the necessary resolution, but often suffer from limited imaging depth, long imaging time, or high light fluence requirements. Here, we present two-photon Super-resolution Patterned Excitation Reconstruction (2P-SuPER) microscopy for three-dimensional imaging of dendritic spine dynamics at a maximum demonstrated imaging depth of 130 μm in living brain tissue with approximately 100 nm spatial resolution. We confirmed 2P-SuPER resolution using fluorescence nanoparticle and quantum dot phantoms and imaged spiny neurons in acute brain slices. We induced hippocampal plasticity and showed that 2P-SuPER can resolve increases in dendritic spine head sizes on CA1 pyramidal neurons following theta-burst stimulation of Schaffer collateral axons. 2P-SuPER further revealed nanoscopic increases in dendritic spine neck widths, a feature of synaptic plasticity that has not been thoroughly investigated due to the combined limit of resolution and penetration depth in existing imaging technologies.

Keywords: super-resolution microscopy, nonlinear optics, neuron, dendritic spine

Graphical Abstract

Existing super-resolution microscopy technologies still cannot achieve high-speed, nanoscopic imaging in deep brain due to strong optical scattering. We developed two-photon Super-resolution Patterned Excitation Reconstruction (2P-SuPER) microscopy, which overcomes these challenges and allows investigating dynamic neuronal processes at new depth.

1. Introduction

Neurons change their morphology and function during development and learning. Investigating these changes in the live brain using optical imaging is complicated by tissue scattering, penetration depth, imaging speed, and the nanoscopic size of critical neuronal and cellular components [1, 2]. Here we report a technique that tackles these challenges and its application to investigating rapid changes in neuronal morphology.

Synapses are the tiny, tight junctions between individual neurons that wire them into circuits. They represent some of the major diffraction-limited neuronal structures. Dendritic spines are membrane protrusions containing the postsynaptic sites of many excitatory synapses in the brain [3]. They change in shape and size in response to neural activity [1, 3–7] and learning [1, 3, 4, 6, 7]. Such changes have been observed at the ultrastructural level using electron microscopy (EM) [8–10], but this technique is incompatible with dynamic imaging and is difficult to combine with functional assays. Nevertheless, several follow up EM studies of functionally interrogated synapses and circuits have been published [8, 11, 12]. An optical imaging tool capable of resolving nanoscopic neuronal components on relevant time scales and at significant depths in scattering tissues could address several controversial topics, including the relationship between synaptic strength and dendritic spine neck parameters (e.g., width, length, and volume). Dendritic spine neck shape is poised to influence voltage and biochemical cascade compartmentalization inside the spine, and the dynamic regulation of these diffraction-limited features has considerable implications for synaptic function.

Recent technological breakthroughs in far-field optical imaging techniques have led to new imaging modalities, collectively referred to as super-resolution light microscopy (SRLM). SRLM has proven valuable in investigating living neuronal circuits and alterations in neuronal morphology [13–19]. Studies using SRLM have revealed new insights into synaptic potentiation [20], electrical compartmentalization in dendritic spines [20, 21], and the role of cytoskeletal dynamics in neuronal plasticity [15, 16, 22].

Despite this significant progress, several drawbacks limit the application of SRLM techniques to nanoscopic neuronal imaging. Certain methods have overcome one of the following limitations, but at the cost of a decrement in another critical property. First, the high average laser fluence required for several super-resolution techniques [13, 16, 18, 19, 21–24] is likely to perturb cellular function and viability [25]. Second, long acquisition time [14, 15, 17–20] prevents accurate imaging of rapid and continuous nanoscopic alterations [4]. Third, due to optical attenuation caused by tissue absorption and scattering, most SRLM technologies cannot maintain nanoscopic resolution beyond superficial depths [14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 22]. To date, no single SRLM technique addresses each of the aforementioned drawbacks simultaneously.

Two-photon laser scanning microscopy (2P-LSM) can extend the depth of imaging in scattering tissue. Several SRLM techniques have combined the principles of 2P-LSM with the enhanced resolution of structured illumination microscopy (SIM). These technologies demonstrate increased resolution (~140 nm) at biologically significant time scales (~1 Hz) [26, 27] at extended penetration depth (110 μm) [26]. However, the reported techniques have lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in scattering media due to optical reconstruction [26] and the use of confocal pinholes in tandem with microlens arrays [27]. Moreover, standard 2P-LSM systems require extensive modification in these SRLM techniques [26, 27].

We previously reported an imaging technique, two-photon scanning patterned illumination microscopy, which employs patterned 2P laser excitation and frequency domain SIM reconstruction to increase optical resolution and imaging depth of SRLM [28]. Although this method simultaneously addressed some of the aforementioned drawbacks, it was limited in dynamic imaging applications due to its modulation implementation, which constrained resolution, contrast, and imaging rate (see Supporting Information). In this report, we introduce two-photon Super-resolution Patterned Excitation Reconstruction (2P-SuPER) microscopy. It uses cascaded electro-optical modulators (EOMs) and integrated adjustable magnification optics to improve spatial resolution, imaging depth, and imaging rate, while adding multicolor imaging capability and reducing excitation fluence. After validating the resolution (approximately 100 nm) and penetration depth (> 130 μm) of 2P-SuPER, we used it to image nanoscopic neuronal architecture in the neocortex and the hippocampus, investigating dendritic spine dynamics associated with plasticity induction.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental setups

We designed 2P-SuPER based on a commercial inverted microscope (IX81, Olympus). The output beam of an 80 MHz Ti:Sapphire laser with 100-fs pulse width (Mai Tai, Newport) first passed through a beam condenser before being routed through two electro-optic modulators (EOMs) (350-160-02-Bk, 350–80 LA-BK-02, Conoptics, Inc.) cascaded in series to sinusoidally modulate the beam (see Supporting Information). Next, the beam was directed to the microscope body after passing through a two-dimensional galvanometer scanning mirror system (QS-7 OPD, Nutfield) and a telescopic beam expander (magnification ratio: 125/30). The NIR excitation light entering the microscope was reflected off a dichroic beam splitter (69218, Edmund Optics) and projected onto the sample through a 1.4-NA 100x oil immersion objective (UPlanSApo, Olympus). Imaging was confined to near the aplanatic point of the objective to minimize spherical aberrations. We used a custom LabVIEW™ program to synchronize the galvanometer scan and the sinusoidal modulation frequency of the EOMs to produce the desired patterned illumination field onto the imaging plane (Figure 1). To collect fluorescence emission, we used an NIR filter (49822, Edmond Optics) and a custom-made filter wheel with blue (FF01–439/154–25, Semrock), green (FF01–550/88–25, Semrock), and red (FF02–641/75, Semrock) band-pass filters before the EMCCD (C9100–13, Hamamatsu). We also used an adjustable magnification lens system (UltraZoom 6000, Navitar) to control the pixel size and imaging plane on the EMCCD. The EMCCD exposure duration matched one patterned illumination. We acquired images corresponding to nine illumination patterns with three angles and three phases [28] for reconstruction.

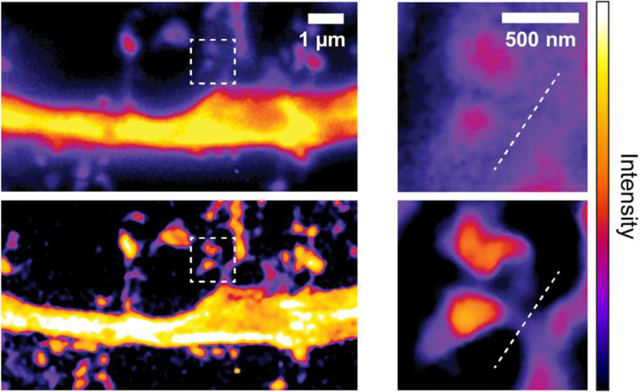

Figure 1.

2P-SuPER microscopy imaging structural correlates of synaptic plasticity. (a) Illustration of 2P-SuPER imaging geometry. A grid patterned illumination field is projected onto the region of interest through a high NA objective. (b) Epifluorescence image of the hippocampal region of the brain slice indicated by the red box in (a). DG: dentate gyrus. The stimulation electrode is placed at the Schaffer collateral pathway between the CA1 and CA3 regions to induce LTP (white circle). Scale bar: 500 μm. (c) Magnified epifluorescence image of basal dendrites in the CA1, within the dashed box indicated in panel (b). We imaged pyramidal neuron dendrites using 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER microscopy in the proximity of the white arrow shown in (c). Scale bar: 100 μm. (d) Comparison of 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER images of a spiny neuron from the CA1 region indicated by the white arrow in (c). Scale bar: 2 μm. (e) Images of dendritic spine necks and heads acquired before stimulation (baseline), immediately after stimulation (0 min), 5 minutes after, and 10 minutes after stimulation. The 2P-SuPER results (middle row) were used to create a diagram of dendritic spine morphological changes induced by electrical stimulation. Bar: 500 nm.

Point detection 2P-microscopy was conducted on a Scientifica upright multiphoton microscope. The output beam of an 80 MHz Ti:Sapphire laser with 70-fs pulse width (Mai Tai eHP DS, Newport) was directed into an two-dimensional galvanometer scanning mirror system (HSA Galvo 8315K, Cambridge Technology) and reflected through a telescopic beam expander before entering the microscope body. The beam was scanned onto the sample through a 1.4-NA 100x oil immersion objective (UPlanSApo, Olympus). Fluorescence emission was collected by a PMT (H10770P, Hamamatsu) after passing through a dichroic beamsplitter (FF670-SDi01–26×38, Semrock) and a bandpass filter (FF02–520/28, Semrock). We used Scanimage 3.8 to control scanning parameters and image acquisition [38].

2.2. Image reconstruction and processing

We achieved super-resolution image reconstruction using custom routines written in Matlab software (R2015a, Mathworks, Inc.). For super-resolution image reconstruction, we first recovered the unattenuated frequency spectrum by Weiner filtering each individual patterned image. The parameters of the Weiner filter, including the system PSF and SNR, were predetermined based on image analysis of illumination patterns imaged from a fluorescein dye solution. We then performed two-dimensional Fourier transformation on each image to convert them to k space. After a 4-fold up-sampling, we gained precise control of the frequency shift (up to 1/4 of the pixel resolution). The precise modulation angle and frequency were determined by analyzing the location of the first-order harmonics as they appeared in the two-dimensional spectrum image. After determining the modulation frequency and angle, we estimated the phase retardation by shifting and matching the theoretical cosine pattern against the original image in the spatial image. The corresponding baseband spectrum and modulated high frequency components were recovered using matrix-based image algebra. The recovered frequency components were then reshaped into a 2D matrix and shifted back to their spatial positions for image reconstruction. Background was subtracted from both 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER images post-reconstruction using a background file acquired at the experimental imaging conditions with the laser shutter closed. After background subtraction, the dynamic range of both the 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER images were equivalently adjusted to optimize the 2P-SuPER image. All quantitative data analysis was conducted from the raw images.

2.3. Fluorescein solution

We used fluorescein (F2456, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in water solution (0.1mg/dL) to visualize the illumination patterns and determine their corresponding frequency domain distributions by preforming Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on the image.

2.4. Quantum dots and fluorescence sphere imaging

We used CdSe/ZnS quantum dots (748099–10MG, Sigma-Aldrich; peak emission wavelength: 600 nm; diameter: ~7.5 nm) to quantify the spatial resolution. Quantum dots were first dispersed in benzene solvent and spin-coated onto a glass cover slide. The solution was allowed to dry before a drop of glycerol was placed over the imaging area to minimize optical scattering at the glass-air interface. We imaged the quantum dots at 780-nm excitation wavelength with an incident fluence of < 10 kW/mm2. To quantify spatial resolution, we measured the FWHM values of 25 randomly selected intensity profiles from all imaged quantum dots under 0.11-Hz and 1-Hz imaging rates. We also measured the minimum resolvable distance between two nearby quantum dots (Figure 2). The nearby quantum dot pair was considered resolved if a 20% intensity decrease between the peak-to-peak intensities could be observed.

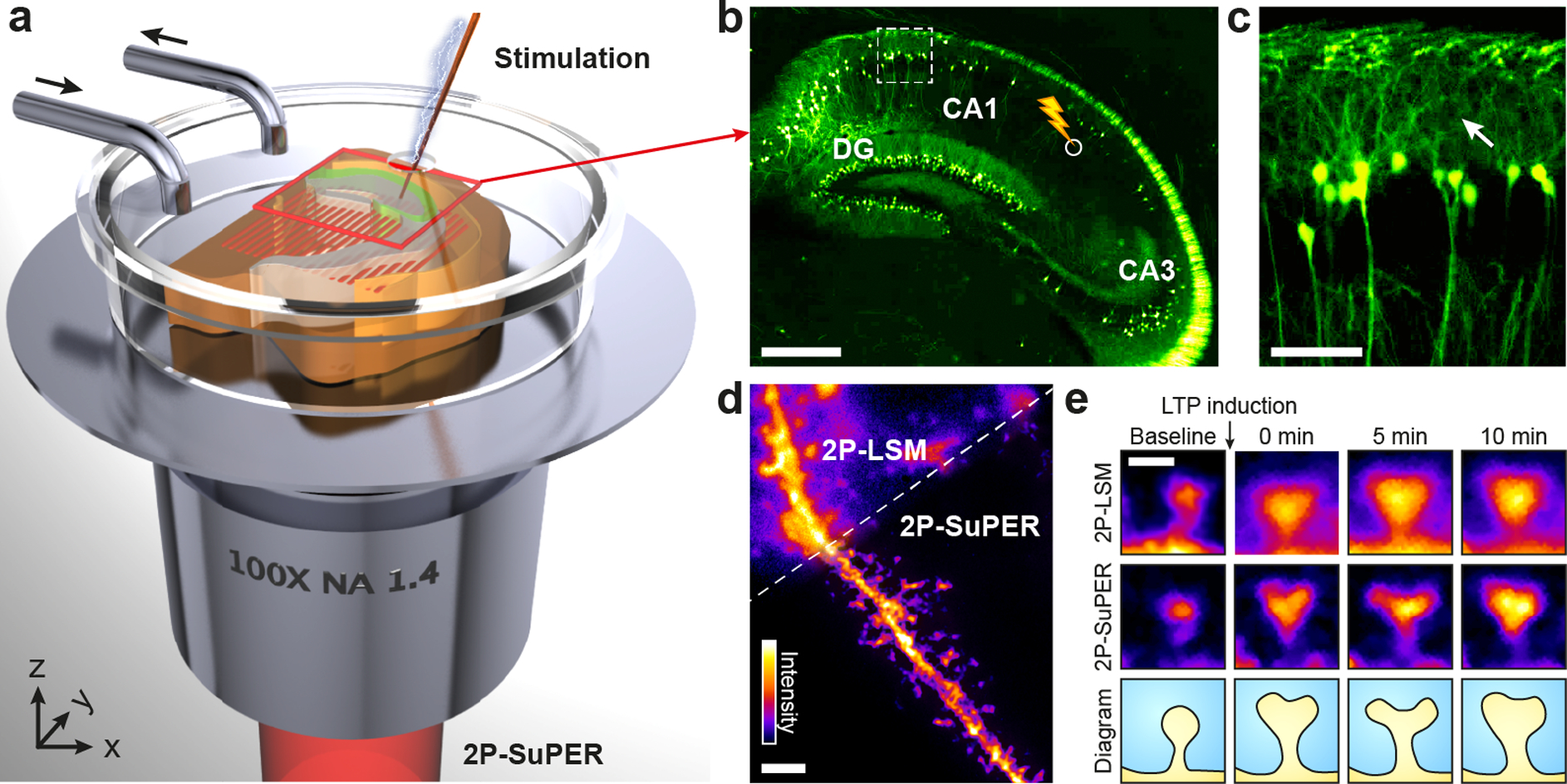

Figure 2.

Demonstration of improved spatial resolution and multicolor imaging capability of 2P-SuPER. (a) Comparison of 2P-LSM (grayscale, above dashed line) and 2P-SuPER microscopy (colored, below dashed line) imaging of red quantum dots (emission peak 600 nm, excited by a 780 nm laser beam). Scale bar: 2 μm; (b) Magnified region of the 2P-LSM image, indicated by the dashed box in panel a. Scale bar: 200 nm; (c) Same as panel b, but for 2P-SuPER; (d) Intensity profile of nearby quantum dots, shown by the dashed lines in panels b and c, imaged using 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER microscopy; (e) Quantified spatial resolution of 2P-SuPER microscopy at two imaging speeds of 100 nm green fluorescent nanospheres. Boxes reflect the mean FWHM measurements of intensity profiles across the center of fluorescent points; error bars reflect s.e.m; (f) Comparison of multicolor 2P-LSM (top, above dashed line) and multicolor 2P-SuPER microscopy (bottom, below dashed line) imaging of green and red fluorescent nanospheres (respective emission peaks of 485 nm and 585 nm, excited by a 830 nm laser beam). Scale bar: 1 μm; (g) Magnified region of the 2P-SuPER image indicated by the dashed box in panel f. Scale bar: 500 nm; (h) Intensity profiles of three multicolor nanospheres, shown by the dashed line in panel g, imaged using 2P-SuPER microscopy. FWHM measurements of the intensity profiles in panel h demonstrate the increased resolution of 2P-SuPER for both color nanospheres.

We used 190-nm green (Fluoresbrite Plain YG 0.2 Micron Microspheres, Polyscience, Inc.) and 210-nm red (FluorophorexTM Polystyrene Nanospheres Cat. No. 2203, Phosphorex, Inc.) fluorescent spheres for multicolor imaging. We mixed the spheres in equal concentrations and spin-coated onto a class cover slide. The excitation wavelength was 830 nm.

2.5. Animal procedures

Thy1-eGFP male and female mice were used in the experiments (Thy1-eGFP, stock # 007788, Jackson Laboratory). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Northwestern University and conformed to the guidelines on the Use of Animals from the National Institutes of Health.

2.6. Acute brain slice imaging

For cortical and hippocampal imaging, acute brain slices (300 μm-thick) were prepared from postnatal day 23–40 Thy1-eGFP male and female mice. Mice were deeply anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and sacrificed. Brains were placed into ice-cold, continuously carbogenated (95% O2/ 5% CO2), artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 127 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, and 25 Glucose (osmolality ~310 mOsm/L). Brains were blocked and sectioned on a Leica VT1000s (Leica Instruments, Nussloch, Germany) in a coronal or transverse orientation. Acquired slices were placed in a continuously carbogenated ACSF solution at 34°C for ~20–30 minutes. After recovery, slices were kept at room temperature until use. During imaging, individual brain slices were placed in a flow chamber with a coverslip window and circulating carbogenated ACSF solution.

Imaging was targeted at eGFP-positive spiny pyramidal neurons in superficial layers of retrosplenial, perirhinal/ectorhinal cortices and hippocampal CA1 pyramidal region. To measure dendritic spine parameters on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in acute brain slices, we varied imaging depth from 35 μm to 135 μm (Figure 3) and used 830–850-nm excitation wavelengths. Average beam power was kept between 3 and 15 mW at the objective back aperture, translating into maximum fluence of under 310 kW/mm2 at the sample due to power loss across the objective. During image acquisition, the beam was scanned over the entire field of view of the 512 × 512 detector at a frame rate varying from 1 to 9 fps. A total of 9 frames were collected at the phases and angles previously described to reconstruct a super-resolution image, corresponding to 2P-SuPER imaging rates of 0.11 Hz to 1 Hz. At least five measurements were taken at each depth from the narrowest observed dendritic spine necks.

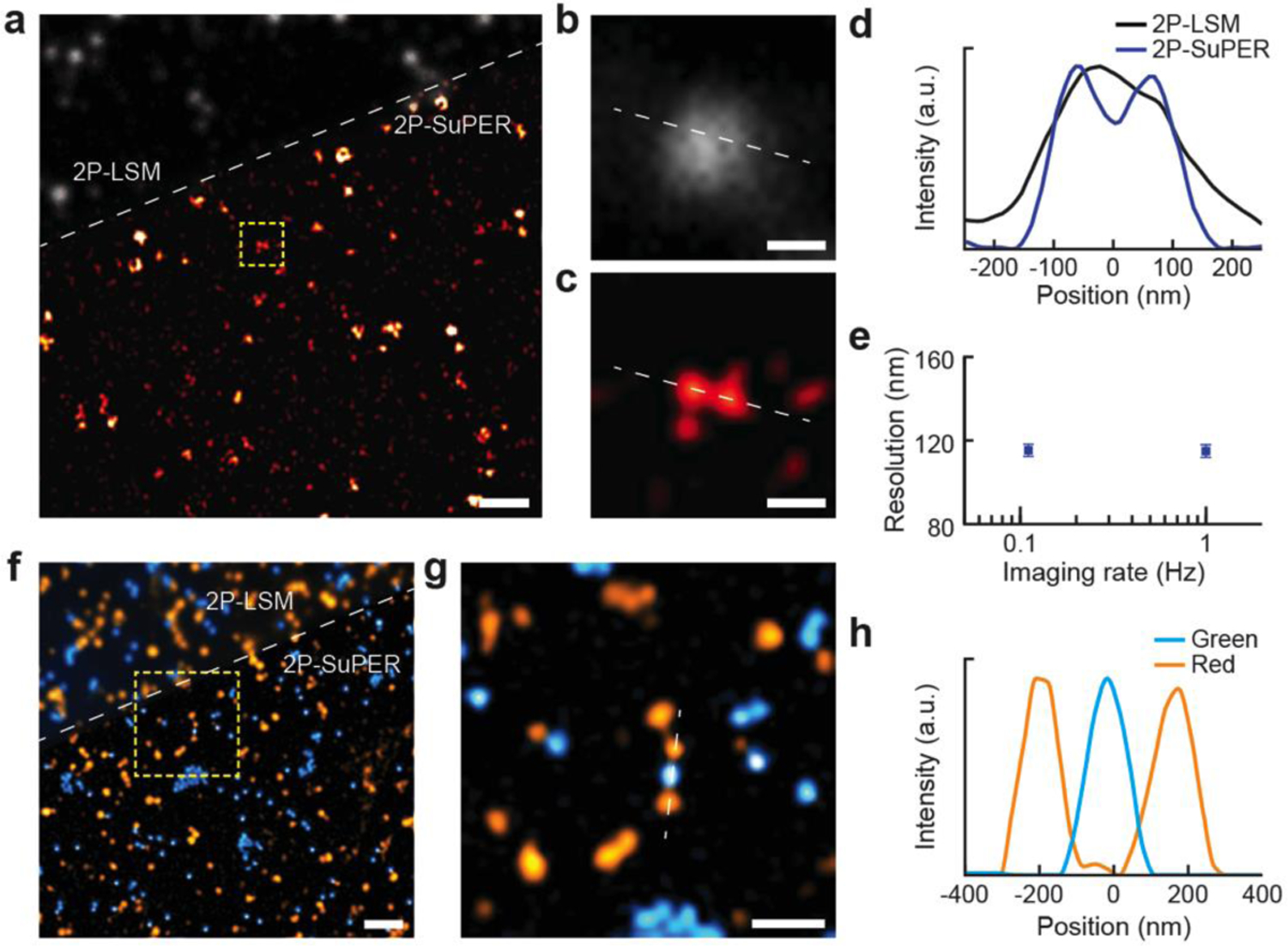

Figure 3.

Comparison of 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER imaging of dendrites at different depths. (a) A volumetric rendering of dendrites located 35 μm and 135 μm from the surface in a 300 μm-thick acute brain slice, imaged using 2P-LSM (left) and 2P-SuPER microscopy (right); (b) Projection images of the three-dimensional volumes shown at 35 μm, as indicated by the top red arrow in panel a, imaged by 2P-LSM (top) and 2P-SuPER microscopy (bottom). Scale bar, 1 μm; (c) Magnified views of the imaged regions highlighted by the dashed boxes in panel b. Scale bar: 500 nm; (d) Sum intensity projection of the three-dimensional volumes at 135 μm, as indicated by the bottom red arrow in panel a, imaged by 2P-LSM (top) and 2P-SuPER (bottom). Scale bar: 1 μm; (e) Magnified views of the imaged regions highlighted by the dashed boxes in panel d. Scale bar: 500 nm; (f) Intensity profiles of dendritic spine necks 35 μm from the surface of the brain slice acquired by 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER, as indicated by the dashed lines in panel c; (g) Same as panel f, but 135 μm from the surface of the brain slice; (h) Average lateral resolution of 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER microscopy, quantified by measuring the neck width of dendritic spines located at different depths in the acute brain slice. Error bars reflect s.e.m; (i) Comparison of dendritic spine neck width measurements using 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER microscopy, all measurements are boxed in 30 nm bins; (j) Same as panel i, but for dendritic spine neck length; (k) Same as panel i, but for dendritic spine head width.

For fixed brain slice experiments, the brain from a postnatal day 27 Thy1-eGFP male mouse (Jackson Laboratory) was sectioned. To create fixed tissue samples, the mouse was given cardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After fixation, the brain was sliced in 300 μm-thick sections on a Leica VT1000s in a coronal orientation. We used the same imaging parameters as for acute brain slices, described above.

2.7. Imaging LTP-evoked changes in dendritic spines

For hippocampal electrical stimulation, we inserted the tip of a concentric bipolar microelectrode (CBAPB75, FHC, Inc.) approximately 10 μm below the surface of the brain tissue at the Schaffer collateral (SC) pathway between the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 region (Figure 4). A custom LabVIEW program was used to control a multifunction I/O device (National Instruments, PCI-6115) to send a TTL signal to a constant current stimulator (AutoMate Scientific, DS3). LTP was elicited by high-frequency theta-burst stimulation, consisting of five stimuli trains with an intertrain interval of 10 seconds. Each train consisted of 10 bursts at 5 Hz, with each burst containing four pulses (80 μs pulses at 700 μA amplitude) at 100 Hz. Images were collected directly before stimulation (baseline), directly after imaging (t=0 min), 5 minutes after stimulation (t=5 min), and 10 minutes after stimulation (t=10 min). Spine neck lengths, widths, and head volumes from images generated by 2P-SuPER microscopy were determined using ImageJ software. Neck lengths were traced from the parent dendrite base to the spine head. The FWHM of the intensity profiles, taken at the narrowest regions of the spine neck, were used to approximate neck radius. We determined the volume of the neck and head using previously described methods [13].

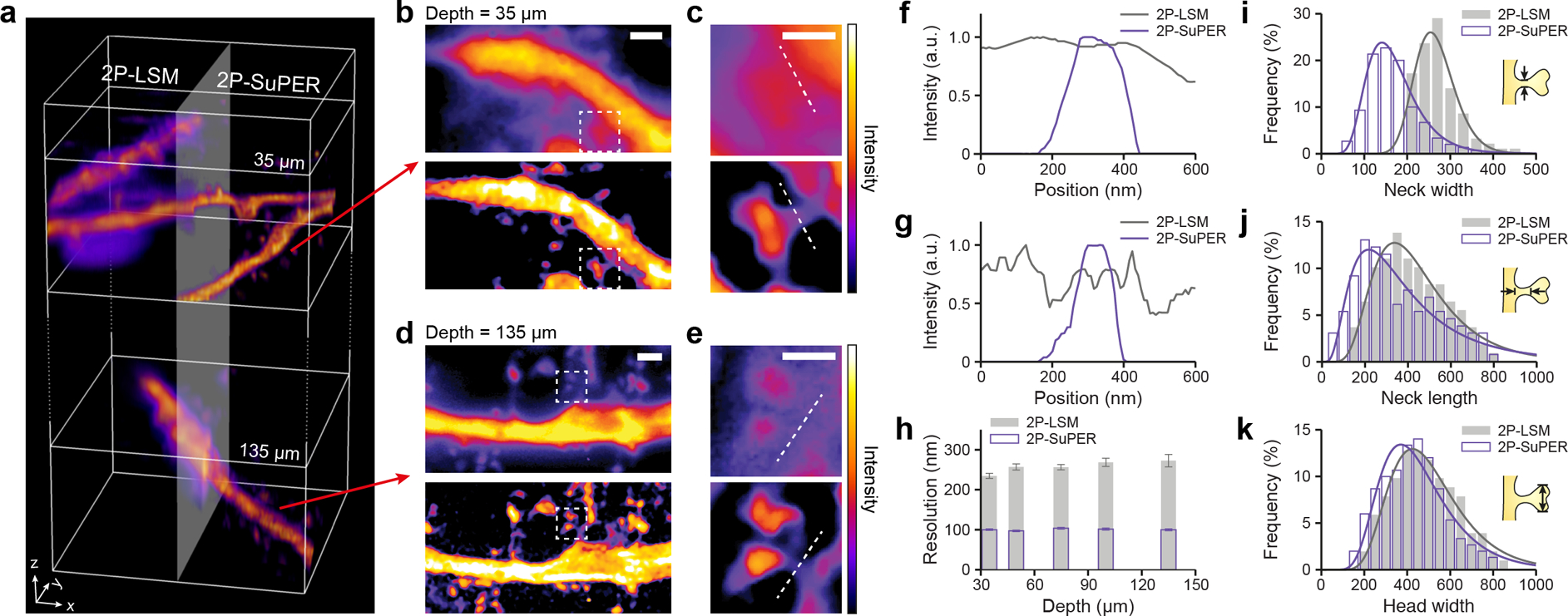

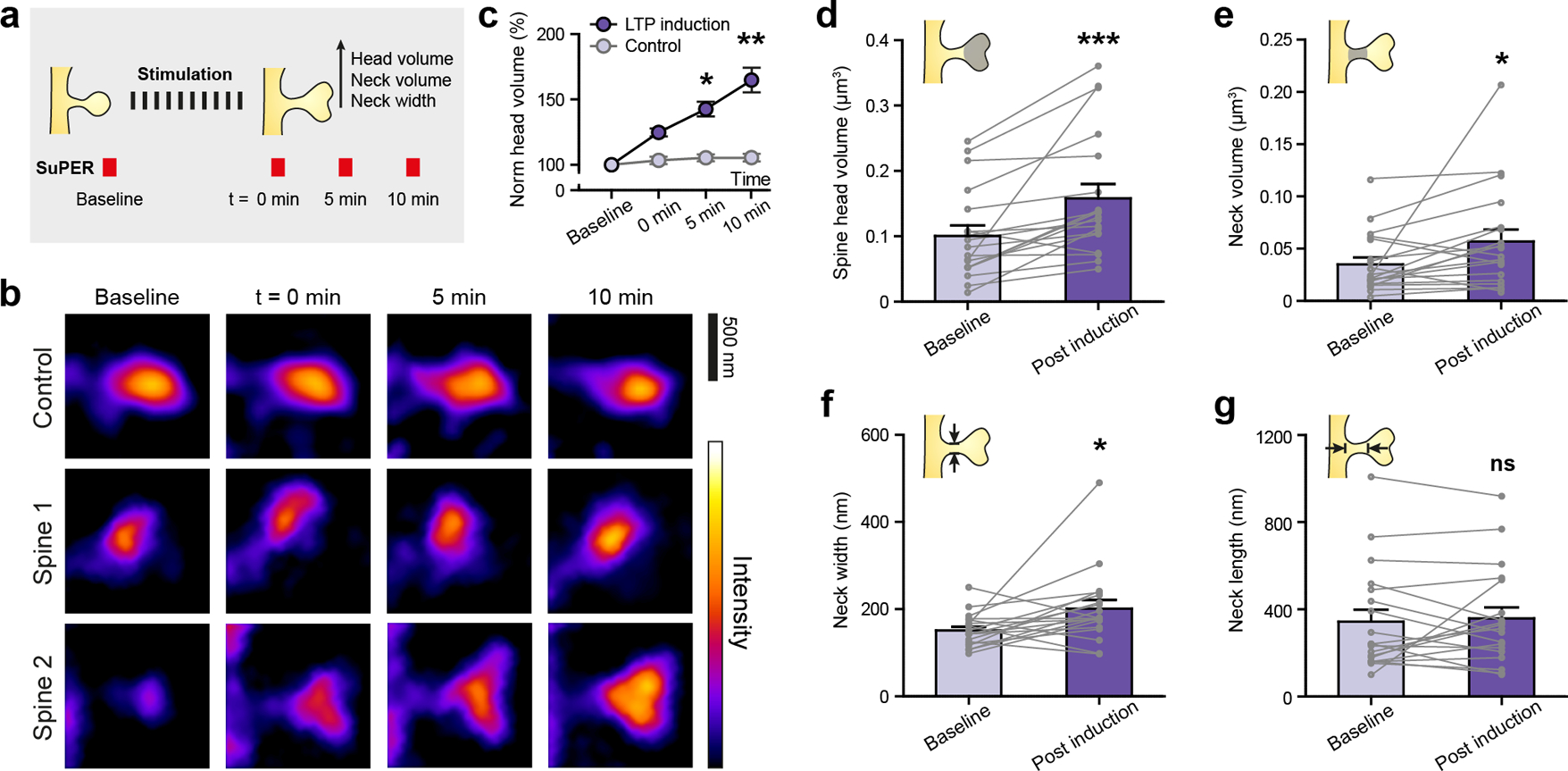

Figure 4.

2P-SuPER microscopy time-lapse imaging of LTP-associated changes in dendritic spines of CA1 neurons. (a) LTP induction protocol and 2P-SuPER imaging timeline. Time-lapse images were acquired before, immediately after, 5 minutes, and 10 minutes after stimulation, as indicated in panel b; (b) Time-lapse images of a control dendritic spine (top) and two dendritic spines (middle and bottom) which received LTP induction protocol; (c) Average percent change in dendritic head volume over time (baseline, 0 min, 5 min, and 10 min). Circles reflect mean value; error bars reflect s.e.m; (d) Average dendritic spine head volume change 10 minutes after stimulation (post-induction). Circles reflect individual spines; lines between circles indicate change of each spine from Baseline to Post induction; error bars reflect s.e.m. (e) Same as panel d, but for neck volume; (f) Same as panel d, but for neck width; (g) Same as panel d, but for neck length.

2.8. Data Analysis

Error bars in all figures reflect the standard error of the mean (s.e.m). We used GraphPad software for all statistical comparisons. All tests were two-sided with a 0.05 level of significance. We used the asterisk symbol to represent P value significance as follow: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. 2P-SuPER microscopy image acquisition

We combined temporal modulation of the 2P excitation beam with carefully controlled raster scanning to pattern illumination. We routed the excitation beam through two cascaded electro-optic modulators (EOMs) to achieve near 100% modulation depth and scanned it onto the imaging plane by a two-dimensional galvanometer (Figure 1a). We varied the delays between the driving voltages of the EOMs and the galvanometer to create nine illumination patterns with three phases (0, 2π/3, and 4π/3) and three equally spaced angles (50°, 170°, and 290°) [28]. We detected the induced fluorescence emission using a high quantum efficiency (> 90%) electron-multiplied charge coupled device (EMCCD). We set the EMCCD exposure time to integrate over each patterned illumination scan. For multicolor imaging, we added an electrically controlled filter wheel in the detection path. To regulate pixel size, we added an adjustable magnification optical assembly before the EMCCD (see Supporting Information). We used epifluorescence microscopy (illumination wavelength: 460 nm) to select imaging regions and guide bipolar electrode placement in eGFP-expressing acute brain slices (Figure 1b). We imaged basal dendrites of cortical and hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons with 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER microscopy, comparing image resolution (Figures 1c & 1d). In addition, we conducted time-lapse imaging of dendritic spine alterations in response to stimulating excitatory inputs to CA1 pyramidal neurons with a bipolar electrode (Figure 1e).

3.2. Spatial resolution of 2P-SuPER

We experimentally quantified the resolution of 2P-SuPER microscopy by imaging fluorescent quantum dots (748099–10MG, Sigma-Aldrich) with emission peak at 600 nm, spin-coated on a cover glass slide (Figures 2a–2e). Full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) measurements of intensity profiles across the center of imaged single quantum dots gave an average value of 97.5±1.6 nm for 2P-SuPER microscopy (92% of 2P-SuPER theoretical resolution). By comparison, the average 2P-LSM resolution was 264.8±7.1 nm (83% of Abbe’s theoretical resolution) using the same objective lens (Figure 2e). To evaluate whether the resolution of 2P-SuPER is independent of scan speed, we imaged 100-nm green nanospheres (Fluoresbrite Plain YG 0.1 Micron Microspheres, Polyscience, Inc.), which provided more photons than QDs when using higher scanning speeds. Increasing the imaging rate by an order of magnitude did not decrease resolution (Figure 2e), but faster imaging narrowed the reconstructed region due to the backlash of galvanometer scanning at high speeds (see Supporting Information). Next we demonstrated the multicolor imaging capability of 2P-SuPER microscopy using 200-nm green (Fluoresbrite Plain YG 0.2 Micron Microspheres, Polyscience, Inc.) and red (FluorophorexTM Polystyrene Nanospheres Cat. No. 2203, Phosphorex, Inc.) fluorescent nanospheres (Figure 2f). As shown in Figures 2g & 2h, 2P-SuPER achieved higher resolutions in multicolor imaging as compared with 2P-LSM and distinguished individual red and green spheres.

3.3. Imaging dendrites in acute brain slices in 3D

To demonstrate the application of 2P-SuPER to imaging genetically encoded fluorescent proteins, we prepared and imaged 300 μm-thick acute cortical brain sections from Thy1-eGFP mice (Jackson Laboratory, #007788, line M) at 400-nm axial step size. We used an 830-nm wavelength for excitation and limited the average laser power to 3–15 mW at the back aperture of the objective lens, corresponding to laser fluence of 68–310 kW/mm2 at the imaging plane using the current objective. Imaging was performed 35–135 μm below the surface of the slice at imaging rates between 0.6 Hz and 1 Hz. Volumetric rendering and sum intensity Z-projections of the acquired dataset are shown in Figure 3a–e, confirming approximately 100-nm spatial resolution at depths up to 135 μm. Using an array detector is necessary in 2P-SuPER in order to achieve Fourier domain reconstruction [28]. In addition, the array detector’s quantum efficiency (QE) is over two-fold greater than high QE photomultiplier tubes, allowing for more sensitive signal detection at the cost of reduced contrast of 2P-LSM in scattering tissue.

Next, we compared 2P-LSM and 2P-SuPER images of dendritic spine parameters at different depths in the slice (Figure 3f–3h). While the majority of dendritic spine heads can be imaged using 2P-LSM, some dendritic spine necks are beyond the best diffraction-limited resolution. We measured the width of 5–7 dendritic spine necks at varying depths, from 35 μm to 135 μm. The smallest observed neck width ranges from 95 nm to 115 nm (Figure 3h). We measured dendritic spine neck width and length, as well as dendritic spine head width using both techniques on the same system (Figure 3i–3k). Demonstrating the advantage of 2P-SuPER, the smaller neck width distributions differ between the two imaging modalities, while the larger structures, such as dendritic spine neck lengths and head widths are increasingly more comparable. We compared the influence of background scattering between 2P-LSM images acquired using point detector and array detector and found that 2P-SuPER can achieve comparable contrast-to-background ratio to a point-detection 2P-LSM using lower illumination power (see Supporting Information).

3.4. Imaging structural plasticity in dendritic spines

After demonstrating static imaging of nanoscopic neuronal structures, we used 2P-SuPER to monitor dendritic spines following electrical stimulation known to induce long-term plasticity (LTP) in CA1 pyramidal neurons [29–32]. 2P-SuPER resolved smaller dendritic neck widths, compared to 2P-LSM, justifying its use in imaging plasticity-associated structural changes in dendritic spine necks, which serve to compartmentalize voltage and synaptic signaling biochemical cascades. To this end, monitoring structural dynamics requires sufficient imaging speeds, available in 2P-SuPER.

Transverse hippocampal brain sections were prepared from mice of both sexes, aged 23–40 days. Plasticity was induced using theta-burst stimulation protocols at the Schaffer collateral inputs to CA1, as described previously [33]. We used 2P-SuPER microscopy to acquire images of CA pyramidal cell proximal dendrites in the baseline condition, as well as immediately after, 5 minutes after, and 10 minutes following the stimulation protocol (Figure 4a). We maintained an imaging rate of 0.1 Hz for better SNR. For each dendrite, we acquired six super-resolution images at 400-nm axial steps and calculated the sum-intensity-projection along the z-axis of the image stack. We used 2P-SuPER to quantify LTP-induced nanoscopic changes in dendritic spine head and neck parameters.

Figure 4b shows time-lapse images of dendritic spines before and after LTP induction using 2P-SuPER microscopy. No changes were observed in dendritic spines, imaged over time in the absence of stimulation. Performing within mouse control experiments, we confirmed that the growth of dendritic spine head volume required the stimulation protocol (Figure 4c) (n=6 dendritic spine heads). To better understand the structural dynamics associated with CA1 LTP, we quantified the average length, width, and volume changes [13] of dendritic spine necks and heads (n=18 dendritic spines). We found that the stimulation increased both dendritic spine head and neck averaged volumes, by approximately 54±15% and 57±30%, respectively (Figures 4d & 4e). Although neck width consistently increased after stimulation (Fig. 4f), neck length rarely increased significantly (Figure 4g). Indeed, plasticity induction frequently led to an apparent contraction of dendritic neck length (10 out of 18 measured necks decreased in length, Figure 4g). Therefore, the evident neck volume growth associated with plasticity induction is driven primarily by the increases in dendritic spine neck width.

4. Conclusion

2P-SuPER attempts to tackle the collective challenges in optical imaging to simultaneously achieve nanoscopic resolution, reasonable penetration depth, sufficient imaging rate, and multicolor imaging. The imaging rate was limited primarily by the scanning speed of the galvanometer mirrors, suggesting potential for further increase. In this work, we used an EMCCD detector to maximize the number of detected photons due to its high QE compared to more commonly employed PMTs. Using an array detector instead of a point detector in 2P-LSM may have stronger background signal due to optical scattering; however, our studies showed that Fourier reconstruction can improve the contrast-to-background ratio to a level similar to that in point-detection. 2P-SuPER relied on two cascaded EOMs to modulate the excitation light amplitude and achieve patterned illumination on the sample. They can be added to existing commercial 2P-LSM systems without extensively modifying the hardware, making 2P-SuPER readily accessible to the broad biological imaging community.

In our study, we focused on monitoring dendritic spines, the sites of many excitatory synapses in the brain [6]. While imaging dendritic spine heads in living neurons is relatively simple using canonical 2P imaging due to their fairly large size [2, 12, 34, 35]; dendritic spine necks tend to be narrow (~ 0.1–0.2 μm) [2] and difficult to resolve. Spine neck width and length control synaptic potential, current flow, and molecular diffusion [5] from the spine head to parent dendrite [5, 6, 36]. A recent study characterized a new form of dendritic spine plasticity defined by a rapid shortening of dendritic spine neck and a concomitant increase in synaptic strength [36]. In that study, dendritic spine head changes were not predictive of synaptic strength. This work appears to contrast reports of the correlation between dendritic spine head volume and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor-mediated currents [7] observed by several groups [10, 37–39]. Our data weigh in on this debate, showing that nanoscopic changes in dendritic spine neck width occur in response to electrical theta-burst stimulation, in parallel to increases in dendritic spine head size. Such nanoscopic alterations of spine neck morphology could affect compartmentalization, protein diffusion, and synaptic connection strength [8, 15, 36, 40, 41]. Super-resolution technologies that support deep-tissue imaging of neurons embedded within complex circuits should ultimately help unify these observations by providing precise measurements of dendritic neck and spine volume dynamics in response to neural activity or specific experiences.

While major discoveries in neuroscience have been made using imaging of cell cultures and superficial layers of acute slices or the whole brain, extending imaging depth will provide the field with new opportunities to better understand the dynamics of diffraction limited organelles and structures. With deeper imaging and multicolor capacity, new super-resolution techniques that can attain high imaging rates will open the door to functional imaging of neuronal activity at nanoscopic levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

HFZ acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (DBI-1353952 and CBET-1055379); National Institutes of Health (R01EY026078, R24EY022883, and DP3DK108248); and the Chicago Biomedical Consortium Catalyst Award. YK acknowledges support from the William and Bernice E. Bumpus Foundation Innovation Award; Beckman Young Investigator Award; Whitehall Foundation Grant; NARSAD Young Investigator Grant. We thank Dr. Kevin Jia and Mrs. Julie Ives from Olympus for experimental assistance and Lindsey Butler for genotyping. We thank contributions from summer high school students Hyun Jung (Jennifer) Ryu and Eric Ren, who helped with developing several electronic components in the optical setup and conducting two-color phantom sample imaging. We thank Dr. Nicholas Bannon for helping with point detection 2P-LSM experiments.

References

- [1].Neuhofer D, Henstridge CM, Dudok B, Sepers M, Lassalle O, Katona I, and Manzoni OJ, Front Cell Neurosci 9, 261–275 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nishiyama J and Yasuda R, Neuron 87, 63–75 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Colgan LA and Yasuda R, Annu Rev Physiol 76, 365–385 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fischer M, Kaech S, Knutti D, and Matus A, Neuron 20, 847–854 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bloodgood BL, Brenda L, and Sabatini BL, Science 80, 310(2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nimchinsky EA, Sabatini BL, and Svoboda K, Annu Rev Physiol 64, 313–53 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GCR, and Kasai H, Nature 429, 761–766 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Arellano JI, Benavides-Piccione R, Defelipe J, and Yuste R, Front Neurosci 1, 131–143 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Harris KM and Weinberg RJ, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, a005587(2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bosch M, Castro J, Saneyoshi T, Matsuno H, Sur M, and Hayashi Y, Neuron 82, 444–459 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cardona, Saalfeld S, Preibisch S, Schmid B, Cheng A, Pulokas J, Tomancak P, and Hartenstein V, PLoS Biol 8, :e1000502(2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kuwajima M, Spacek J, and M Harris K, Neuroscience 251, 75–89 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Takasaki KT, Ding JB, and Sabatini BL, Biophys J 104, 770–777 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dani, Huang B, Bergan J, Dulac C, and Zhuang X, Neuron 68, 843–856 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Izeddin, Specht CG, Lelek M, Darzacq X, Triller A, Zimmer C, and Dahan M, PLoS One 6, e15611(2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Urban NT, Willig KI, Hell SW, and Nägerl UV, Biophys J 101, 1277–1284 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Testa, Urban NT, Jakobs S, Eggeling C, Willig KI, and Hell SW, Neuron 75, 992–1000 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tønnesen J, Nadrigny F, Willig KI, Wedlich-Söldner R, and Nägerl UV, Biophys J 101, 2545–52 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bethge P, Chéreau R, Avignone E, Marsicano G, and Nägerl UV, Biophys J 104, 778–785 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tønnesen J, Katona G, Rózsa B, Nägerl UV, Nat Neurosci 17, 678–85 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Takasaki K and Sabatini BL, Front Neuroanat 8, 29(2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Willig KI, Steffens H, Gregor C, Herholt A, Rossner MJ, and Hell SW, Biophys J 106, L01–L03 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nägerl UV, Willig KI, Hein B, Hell SW, and Bonhoeffer T, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 18982–18987 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Giepmans NG, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, and Tsien RY, Science 80, 217–224 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bush PG, Wokosin DL, and Hall AC, Front Biosci 12, 2646–2657 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Winter PW, York AG, Dalle Nogare D, Ingaramo M, Christensen R, Chitnis A, Patterson GH, and Shroff H, Optica 1, 181–191 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ingaramo M, York AG, Wawrzusin P, Milberg O, Hong A, Weigert R, Shroff H, and Patterson GH, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 5254–5259 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Urban BE, Yi J, Chen S, Dong B, Zhu Y, DeVries SH, Backman V, and Zhang HF, Phys. Rev. E 91, 42703(2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Capocchi G, Zampolini M, and Larson J, Brain research 59, 332–336 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Staubli U, and Lynch G, Brain research 435, 227–234 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Larson J, Wong D, and Lynch G, Brain research 368, 347–350 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nguyen PV and Kandel ER, Learning & Memory 4, 230–243 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Espinoza JA, Bohmwald K, Cespedes PF, Gomez RS, Riquelme SA, Cortes CM, Valenzuela JA, Sandoval RA, Pancetti FC, Bueno SM, and Riedel CA, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9112–9117 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].N Bourne J and Harris KM, Curr Opin Neurobiol 22, 372–82 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ballesteros-Yáñez, Benavides-Piccione R, Elston GN, Yuste R, and DeFelipe J, Neuroscience 138, 403–409 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Araya R, Vogels TP, and Yuste R, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, E2895–E2904 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Steiner P, Higley MJ, Xu W, Czervionke BL, Malenka RC, and Sabatini BL, Neuron 60, 788–802 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sturgill JF, Steiner P, Czervionke BL, and Sabatini BL, J Neurosci 29, 12845–12854 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Knott GW, Holtmaat A, Wilbrecht L, Welker E, and Svoboda K, Nat Neurosci 9, 1117–24 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jaskolski F and Henley J, Neuroscience 158, 19–24 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yuste R and Bonhoeffer T, Annu Rev Neurosci 24, 1071–1089 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Pologruto, Sabatini B, and K. Svoboda, Biomed Eng (NY) 2, 1–9 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lu J, Min W, Conchello JA, Xie XS, and Lichtman JW JW, Nano Lett 9, 3883–3889 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yeh H and Chen SY, In SPIE BiOS 858826–858826 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yeh H and Chen SY, Appl Opt 54, 2309–2317 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Débarre, Botcherby EJ, Booth MJ, and Wilson T, Opt Express 16, 9290–9305 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].York G, Parekh SH, Dalle Nogare D, Fischer RS, Temprine K, Mione M, Chitnis AB, Combs CA, and Shroff H, Nat Methods 9, 749–754 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Orieux, Sepulveda E, Loriette V, Dubertret B, and Olivo-Marin JC, IEEE Trans Image Process 21, 601–614 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.