Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been essential for occupational health services (OHS) providers to react rapidly to increased demand and to utilize resources in novel ways. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological well-being of staff is already identified as an area of high risk; therefore, providing timely access to psychological support may be vital, although limited evidence is available on how these risks are best managed.

Aims

To describe implementation and analysis of a psychology-led COVID-19 telephone support line in a National Health Service OHS.

Methods

Data from calls made to the support line were collected over the first 4 weeks of service implementation. Numerical data including frequency of calls and average waiting time were first considered. A content analysis was then conducted on call notes to identify prevalence of themes.

Results

Six hundred and fifty-five calls were received, and 362 notes included sufficient information for use within the content analysis. Frequency of calls peaked within the first week followed by a reduction in the number of calls received per day over time. Most calls included discussion around clarification of guidance (68%) with a smaller subset of calls offering support around anxiety (29%). Prevalence of themes did not appear to change over time.

Conclusions

Clear and timely information is vital to support the well-being of healthcare staff. A psychologically informed telephone support line was a good use of occupational health service resources in the interim while more tailored advice and services could be established.

Keywords: Anxiety, COVID-19, healthcare worker, occupational health services, pandemic

Key learning points.

What is already known about this subject:

COVID-19 is anticipated to have a long-term impact on the mental well-being of healthcare staff.

Occupational health services have a vital role in providing timely and meaningful psychological support to healthcare staff.

Little evidence is available on the most effective mechanisms which can be put in place to reduce the psychological risks for staff working in an acute hospital setting.

What this study adds:

Access to clear, timely information is useful to staff in a healthcare setting, whether this relates to practical and medical considerations or concerns related to well-being.

Demand for support reduces when more tailored advice and services are available but interim support is a good use of resources until more established mechanisms can be put in place.

What impact this may have on practice or policy:

A rapidly implemented psychological support line is feasible and can add value to the initial occupational health service response to a pandemic.

The service can represent a valid use of occupational health service non-medical capacity in providing a meaningful response to staff at a time of significant challenge.

Services should adapt and change over the course of the pandemic based on feedback and demand from staff members.

Introduction

Healthcare workers are at significant risk of adverse mental health outcomes following a pandemic [1]. Evidence from previous pandemics indicates the risk of long-term negative psychological outcomes in healthcare workers including increased levels of stress, depression and anxiety in comparison to non-healthcare workers [2]. The COVID-19 outbreak has already been identified as having a significant impact on mental health [3]. Medical staff report unmanageable workload, increased isolation and experiences of social discrimination; factors which are associated with exhaustion and mood disturbance [4]. Feelings of uncertainty and vulnerability are also escalated in healthcare workers due to increased risk of coronavirus exposure [5]. As well as the risks to physical health, COVID-19 presents a significant risk to the emotional well-being of healthcare staff. Due to the long-term impact COVID-19 is anticipated to have on mental health outcomes, authors emphasize the need for rapid implementation of psychological resources to support staff well-being [6]. Although limited guidance is available on interventions [7], initial evidence indicates digital interventions could be useful in mitigating negative mental health outcomes of COVID-19 [8].

Providers of National Health Service (NHS) occupational health services (OHS) have had to react swiftly to the unprecedented demands of the coronavirus pandemic. The novel and dynamic nature of the situation has created extensive pressures across systems whereby providers have had to take difficult decisions in the face of limited data, including at times suspending ‘business as usual’ to respond to acute organizational needs. As the initial demands may be heavily weighted towards queries about symptoms and medical management, mental health professionals integrated into OHS teams may face the additional dilemma of meaningfully supporting teams whilst usual practice, especially the delivery of face-to-face, structured intervention, may be temporarily untenable.

The OHS consists of an integrated multidisciplinary team providing support for ~14 000 staff. Initially, all OHS enquiries were directed to email as meeting telephone demand was not practicable. Email allowed specificity around delegation of tasks and that details such as pertinent history could be gathered. Template responses could be provided in a timely manner, meaning that all contacts received interim advice whilst more specific processes were being developed. However, in this very challenging and novel situation, it was imperative to re-establish a sustainable and effective telephone-based response as soon as possible. This was considered particularly pertinent where staff may be anxious or distressed and therefore find it more difficult to communicate or interpret email responses effectively. Therefore, the psychology & counselling team lead on the rapid implementation of a telephone support line for individuals without symptoms to access very brief emotional support, containment and signposting to emotional support and other advice.

The telephone line was launched and advertised from 24 March 2020; 1 day after a nationwide ‘lockdown’ was announced in the UK. Phone lines were open from 09:00 a.m. until 17:00 p.m., Monday to Friday. Details of how to contact the support line were added to the Trust intranet page and communicated weekly through the trust daily COVID-19 updates sent by email to all staff. Managers were encouraged to print off information to share with staff unable to access email. The OHS department also had an automatic email response to anyone contacting the department containing guidance on how to access the support line. The support line was advertised as suitable for staff who felt affected by the current situation. It was made clear that this service was not suitable for symptomatic staff and that responders were unable to give specific advice on health-related medical concerns. These concerns were instead directed to email where medical and nursing resources were deployed to respond in a more systematic way. A recorded message indicated the scope of the service and re-directed staff with medical concerns to the appropriate route. The support line was able to offer information and guidance, signpost to resources and refer to a further half-hour support call with a mental health practitioner where required.

The service was set up to be psychologically informed and thus all staff working on the telephone support line were given guidance and support by psychological practitioners, including orientation on the scope of the service and up to three psychology-led meetings throughout the day to explore content of calls or any concerns raised. Call handlers consisted of the OHS counselling & psychology team in the first instance, later supported by staff with an interest in mental health from research and nursing backgrounds.

Despite being advertised as an emotional support service, it was apparent from those taking initial calls that many callers sought advice related to trust and government guidelines and medical symptoms. Considering this, a content analysis was carried out to establish how the initial telephone support line was utilized by staff to inform how capacity might be best used as part of the OHS rapid response going forward. The following paper describes the implementation and analysis of a psychology-led COVID-19 telephone support line in an NHS occupational health setting.

Methods

Following each phone call a brief description of the discussion, subsequent decisions, date and time were recorded on a secure OHS database. Numerical data from the support line were analysed including call frequency and average waiting times. Frequency of calls over time was also considered.

A qualitative evaluation was then conducted on call notes using inductive content analysis to identify common themes across the data set. Themes were identified through review of the data rather than being entered into a pre-existing coding frame [9]. More specific subthemes were first identified and then aggregated into broader overarching themes. Subthemes with similar content were merged to prevent overlap of categories. A second coder reviewed themes to assess accuracy.

Each call was coded semantically as being in one of the thematic groups depending upon the content of the call conversation. Where calls included discussion of several queries, the theme was coded depending upon which topic was discussed most. All calls with complete information from 24 March to 14 April 2020 were coded and analysed to ensure that all relevant data were accounted for within analysis. Coding of each call enabled estimates of theme prevalence.

To ensure rigour within analysis, the reliability of thematic coding was assessed via Cohen’s Kappa (κ). Thematic content was reviewed independently by a second coder for 10% of the calls (n = 39). Cohen’s Kappa classification indicates very good agreement in themes identified for calls across coders, κ = 0.896 (95% CI, 0.786–1.000), P < 0.005 [10].

Use of fully anonymized data did not require ethical approval; however, Trust information governance guidelines were followed and thus the project was entered on the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals clinical effectiveness register.

Results

The support line service was available to ~14 000 staff members employed by a large acute NHS Trust. The population accessing the support line are working age and have a wide range of occupations including those in clinical and non-clinical roles. The service was accessible to those currently at home self-isolating, individuals who have been re-deployed and staff working in their usual roles.

Six hundred and fifty-five calls were received within the first 4 weeks of implementing the telephone support service. Data are presented in the form of frequencies as numbers represent number of calls and not individual people.

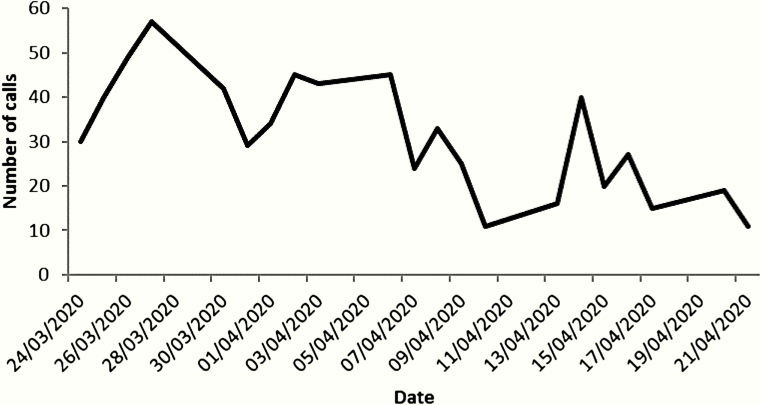

Mean waiting time for callers to be put through to a call handler was 28 s indicating quick response times. Frequency of calls peaked within the first week of service implementation. After this point the number of calls received each day dropped gradually over the next 4 weeks (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total number of calls per day.

The content analysis was carried out on 362 calls (55% of total calls received) where enough data were available for accurate coding. Three key overarching themes were identified including support around anxiety, clarification of guidance and calls which were not COVID-19 related. Key themes have been further reduced to 11 subthemes (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Themes identified resulting from thematic analysis of support line call notes

| Theme | Subtheme | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Support around anxiety | General anxiety/mental health concern | Individuals who are struggling with their mental health due to anxiety around COVID-19 and where previous difficulties have been exacerbated |

| Increased risk of exposure | Worries around increased risk of exposure due to being at work for staff members who do or do not identify as having an underlying health conditions | |

| Vulnerable family member | Individuals who are concerned about putting vulnerable family members at risk by going out to work and potentially bringing the virus back home with them | |

| Absence from work | Staff who are concerned about getting reprimanded or letting others down by not attending work for prolonged periods of time due to shielding or self-isolation | |

| Own symptoms | Worry about severity of own symptoms and the risk of spreading the virus to others including colleagues and patients | |

| Frustration and confusion around guidance | Individuals who feel anxious due to not understanding what the guidance means and how to follow it or feeling frustrated at the rapid changes in guidelines and instability of information provided | |

| Clarification of guidance | Family symptomatic or case contact | What actions to take when a family member is symptomatic or they have been in contact with a symptomatic individual (friend, patient, colleague) |

| Shielding and working when vulnerable | Queries on re-deployment and guidance on working if they have received a shielding letter or identify themselves as at risk due to an underlying health condition | |

| Working when have a vulnerable family member | Requests for guidance on whether working is still appropriate if they are living with a person indicated to be within the high-risk group | |

| Symptomatic | Request for guidance on working when symptomatic and enquiries relating to eligibility for swabbing | |

| Non-COVID-19 related | Requests for information on usual OHS activity including management referrals and immunizations which are not related to COVID-19 |

When looking at the prevalence of themes, the majority of calls were requests for practical information in the form of clarification of guidance (n = 272, 68%; see Table 2). The second most common theme of calls were those which had a supportive nature in allowing staff to discuss their anxieties and concerns (n = 114, 28%). A small percentage of calls were unrelated to COVID-19 (n = 12, 3%).

Table 2.

Frequency of themes identified in the support line call notes

| Themes | Subthemes | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Support around anxiety | General anxiety/mental health concern | 16 (4) |

| Increased risk of exposure | 31 (8) | |

| Vulnerable family member | 20 (5) | |

| Absence from work | 6 (2) | |

| Own symptoms | 28 (7) | |

| Frustration and confusion around guidance | 13 (3) | |

| Total support around anxiety | 114 (29) | |

| Clarification of guidance | Family symptomatic or case contact | 71 (18) |

| Shielding and working when vulnerable | 42 (11) | |

| Working when have a vulnerable family member | 5 (1) | |

| Symptomatic | 154 (39) | |

| Total clarification of guidance | 272 (68) | |

| Non-COVID-19 related | General enquiries | 12 (3) |

Values in bold represent total numbers for overarching themes.

For calls coded as relating to support around anxiety, the largest proportion were from individuals feeling anxious due to the increased risk of exposure associated with their job role (8%). Concerns were expressed by front-line medical workers in regular proximity with the public and/or confirmed COVID-19 patients. However, those working in non-clinical roles also felt conflicted by attending work while the rest of the country was encouraged to self-isolate. Staff members were also concerned about the risk of working when they have a family member at home who they perceive to be vulnerable (5%). This indicates that a notable proportion of individuals who contacted the telephone line for support were those struggling due to concerns that themselves or a loved one were at risk.

Staff also accessed the support line to discuss anxiety relating to the severity of their symptoms and concerns upon whether they are likely to spread the virus to others (7%). There was some confusion around processes of isolation and fear of social stigma upon return to work. Similarly, staff members expressed worry that they would be seen as not contributing to the team effort or seen as letting their patients and colleagues down by missing work (2%). Concerns around missing work also included fear of being reprimanded. Some calls featured discussion of more general mental health difficulties as staff members struggled to cope with changes triggered by the pandemic (4%). Others discussed how long-term mental health difficulties, such as anxiety and depression, had been exacerbated by COVID-19. The support line also received calls from staff members who were frustrated and/or confused by the changing guidance delivered by the trust (3%). Individuals expressed distress at not feeling able to understand guidance while others discussed their frustration at how rapidly it was changing.

The most prevalent theme of calls received on the telephone support line was requests for information on what to do when symptomatic (39%). This included queries related to fitness for work, how to access testing and anticipated response time to emails by the OHS medical team. A smaller proportion of calls featured specific requests for guidance on steps to take when the individual was asymptomatic but had been in contact with someone else displaying symptoms (18%). A number of calls included requests for practical advice on steps which should be taken when they (11%) or when a family member (1%) is viewed as having a high-risk health condition. Staff members were unsure about whether it was appropriate to shield, apply for re-deployment or continue working as usual.

A small number of calls were not related to COVID-19 but instead involved questions about OHS services (3%). This included individuals enquiring about management referrals, immunization clinics and physiotherapy services. Although these calls were not related to guidance or anxiety around COVID-19, they were all necessitated by suspension of usual practice due to the current pandemic.

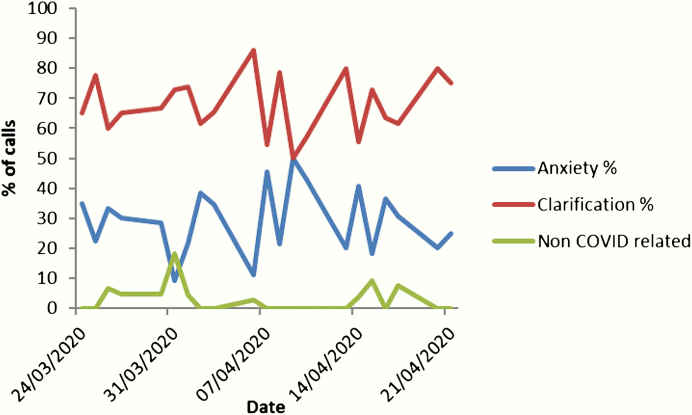

The prevalence of key themes does not appear to differ over time (see Figure 2). Although peaks and troughs in frequency can be seen, calls relating to clarification of guidance are consistently more prevalent than other themes.

Figure 2.

Percentage prevalence of themes over time.

Discussion

Analysis found that many staff accessed the support line with a peak of frequency in the first week. Most calls involved discussion around clarification of guidance whereby staff requested information on symptoms, case contacts and working when they or a family member are vulnerable. A significant subset of calls involved support around anxiety as staff members utilized the support line to discuss general anxieties as well as concerns for themselves, family members, missing work and frustration around guidance.

The paper is novel in being one of the first to evaluate service provision during the COVID-19 pandemic within the UK. In addition, it considers the rapid deployment of non-medical capacity within an established multi disciplinary OHS team services. A strength of the use of thematic analysis is the provision of a flexible tool, allowing rich and detailed understanding of preliminary data [9]. Despite this, there remains an unavoidable level of bias from researchers when coding data which means that interpretation is limited beyond description of themes identified. A further limitation is that the population who were able to access this service was limited to staff members working in the North East of England as part of Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals. As the description of this service is based on calls from a specific group of staff, some caution should be taken in generalizing findings to healthcare workers across different localities.

In an attempt to systematically manage the unprecedented demand of enquiries related to COVID-19, the implementation of a psychology-led telephone support line represented an efficient use of staff capacity in the early stages of the situation. The service could provide responsive communication and support to staff who may have been emotionally affected by COVID-19. As a best attempt at rapid response, the system had face validity to the OHS and wider trust team and informal positive feedback was received from managers. This could be considered to provide a valuable ‘interim’ service whilst other approaches were planned and implemented. Calls peaked during the first week of implementation and tapered off in the following weeks. Reduction in calls could be due to development of other resources including the NHS national line implemented on the 8 April 2020 and release of comprehensive guidelines for specific groups including advice from the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists, the British Heart Foundation and other medical charities. Increased capacity for OHS responsiveness to email queries over time also likely reduced staff member use of the support line. Further exploration of mechanisms is required before the reduction in demand could be interpreted fully; however, areas of interest include the development of improved guidance, the implementation of other services and resources, staff developing skills and confidence in novel situations and successful resolution of outstanding queries.

The results of the thematic analysis of calls did however indicate that despite attempts to be clear that the main role of the support line was for emotional support, the majority of calls were still related to symptoms, guidance and clarification of advice. In response to this, the psychology team developed a quick reference guide to help call handlers signpost staff to guidance resources, whilst reinforcing the importance of avoiding inadvertent ‘clinical decision-making’ during the calls. This pattern aligns with reports from Chen et al. [11] who implemented a telephone support line with the possibility of further psychological interventions. They report that staff early in the pandemic were resistant to this and were seeking more practical support (e.g. protective equipment, skills training, food, places to sleep). Although initial intentions for the emotional support line were not fully realized, staff utilized increased access to information and resources, which could be anticipated to have a positive effect where no other resource was available. This emphasizes the need for rapidly implemented systems to continually evaluate and be responsive to staff needs.

Many enquiries related to clarification of guidance or advice that had already been provided. Brooks et al. [12] suggest that perceived ‘poor’ information from authorities can be experienced as a stressor leading to confusion about the most appropriate action to take. Whilst understandable, Mishel [13] identified that perceived uncertainty related to illness can influence psychological distress, and additional information seeking due to distress may place additional demand on services. When conceptualized as an additional stressor influencing emotional distress, the implementation of psychologically informed informational interventions may be increasingly pertinent. Indeed, an area of interest for preventative interventions going forward is the management of informational interventions and how these may mitigate or contribute to distress.

Although calls related to guidance, symptoms and transactional concerns made up a large proportion of calls; 30% of calls were still directly related to self-identified emotional distress in healthcare workers in the very early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in the UK. This suggests that emotional distress, attributable in part to the COVID-19 outbreak, appeared comparatively rapidly in healthcare staff. Having a psychologically informed service meant that call handlers felt able to offer additional information and refer distressed callers on to emotional support, which may not have been possible had the line not been set up in this way.

Further evaluation of the experiences of those accessing more formal emotional support following this contact is a key next step in evaluating the effectiveness of the OHS rapid response. The results of this can also be used to inform psychological interventions to manage emotional distress in NHS staff as the situation progresses.

In summary, the rapid implementation of a psychology-led emotional support line within an OHS provided a useful learning experience to inform responses to the COVID-19 outbreak and may influence responses to future incidents. Our findings and initial informal feedback suggest that access to clear, timely information is useful to staff in a healthcare setting, whether this relates to practical and medical considerations or concerns related to well-being. Frustration can be experienced by staff when responses are subject to delay or where guidelines feel unclear and rapid interventions should evolve and change based on feedback and demand. We identified that demand reduces when more tailored advice and services are available but that interim support can be a valid use of OHS non-medical capacity in providing a rapid response to staff at a time of significant challenge.

Acknowledgements

We thank the psychology and counselling team within Newcastle OHS including Rachel Saint, Norna Wilkins, Sandra Beswick and Martin Brewster. Thanks also to the support line team for their support in implementing the service.

Funding

No funding received.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;52:102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheng SK, Wong CW. Psychological intervention with sufferers from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): lessons learnt from empirical findings. Clin Psychol Psychother 2005;12:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH et al. . Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16:1732–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsamakis K, Rizos E, J Manolis A et al. . COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on mental health of healthcare professionals. Exp Ther Med 2020;19:3451–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y et al. . Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shah K, Kamrai D, Mekala H, Mann B, Desai K, Patel RS. Focus on mental health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: applying learnings from the past outbreaks. Cureus 2020;12:e7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH et al. . Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London and New York: Chapman and Hall, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y et al. . Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e15–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE et al. . The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020;395:912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mishel MH. Uncertainty in illness. Image J Nurs Sch 1988;20:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]