Abstract

As a global crisis, COVID-19 has underscored the challenge of disseminating evidence-based public health recommendations amidst a rapidly evolving, often uncensored information ecosystem—one fueled in part by an unprecedented degree of connected afforded through social media. In this piece, we explore an underdiscussed intersection between the visual arts and public health, focusing on the use of validated infographics and other forms of visual communication to rapidly disseminate accurate public health information during the COVID-19 pandemic. We illustrate our arguments through our own experience in creating a validated infographic for patients, now disseminated through social media and other outlets across the world in nearly 20 translations. Visual communication offers a creative and practical medium to bridge critical health literacy gaps, empower diverse patient communities through evidence-based information and facilitate public health advocacy during this pandemic and the ‘new normal’ that lies ahead.

Keywords: COVID-19, health literacy, patient education, social media, visual aid

Public health information in the time of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic is rapidly becoming the greatest public health crisis of the new millennium. While frontline clinicians and innovative researchers continue to work tirelessly, effective management of this pandemic requires engagement of the public if we are to curb further rises in cases and safely enter a ‘new normal.’ However, despite the unprecedented connectedness that we are afforded in 2020, disseminating useful, accurate public health information has emerged as a major challenge—one exacerbated by the exponential growth of unverified COVID-19-related information on social media platforms.1 Critical health literacy gaps further threaten the equity of information access among racial minorities and other vulnerable communities, which are already being disproportionately affected by the pandemic (e.g. 36% of African Americans aged 16–64 in the lowest literacy bracket).2–4 In this piece, we propose that simple, validated pictorial presentations of data, or infographics—situated at a unique intersection of the arts and public health—can be effective tools to deliver medical information during this pandemic.

A picture is worth a thousand words

Visual aids and graphics are a powerful medium and have a long history in the broader field of education research, which suggests that the combination of words and simple images into a unified model enhances learning and information retention.5 During the current COVID-19 pandemic, visuals have emerged as a particularly powerful vehicle of information dissemination. Perhaps, the best-known example is the ‘#flattenthecurve’ graphic, a widely circulated image showing the anticipated effects of social distancing efforts. However, there remains a need for simple illustrated resources that consolidate key public health messages and validated clinical evidence into compact visual aids—especially those that can be seamlessly disseminated through social media outlets to reach diverse patient communities.

A validated COVID-19 infographic

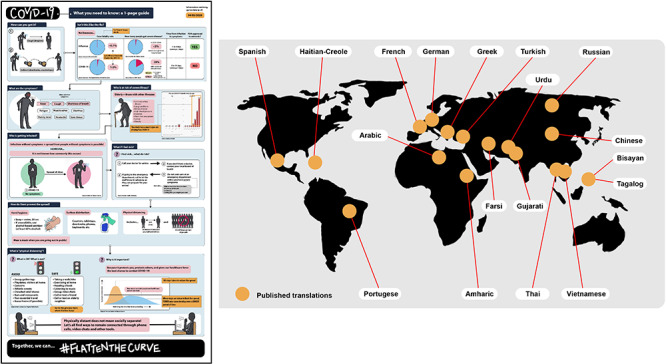

We addressed this need by creating a single-page infographic designed to educate the public about essential COVID-19-related content (Fig. 1). Evidence-based information, ranging from mechanisms of transmission and risk factors to comparative epidemiological statistics between influenza and COVID-19, was compiled and reviewed. We distilled this information into a simple infographic with the goals of (i) informing a layperson reader and (ii) guiding providers through a typical conversation about COVID-19 with a loved one, curious patient or the larger public. In order to cater toward a diverse range of health literacy levels, overly complex medical terminology was avoided (i.e. replacing ‘shock’ with ‘severely low blood pressure’), and each graph was annotated with simple interpretations of the data in accessible language to guide interpretation and circumvent potential ‘numerical overload.’ The final piece underwent rigorous peer review by a team of physicians, including experts in infectious disease, public health and medical education.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 Infographic. Our validated, one-page infographic curates essential COVID-19 information for patients and the lay public into a simple and accessible visual layout. Non-English versions have been created in nearly 20 languages, as captured by the map, to reach diverse patient communities.

Closing the gap: leveraging the power of social media

In the first week following its release on social media, the infographic reached more than 120 000 people, with nearly 600 readers sharing it among USA and international medical schools, residency and fellowship programs, local municipal governments and even networks of professional comic and graphic artists. To better reach vulnerable communities at risk of limited access to information, the infographic was shared specifically with physician leaders and organizations focused on eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. While virtual validation and increased social media visibility cannot be directly extrapolated to public health impact, they do underscore the synergy between social media and effective infographics in promoting rapid transmission of information across interdisciplinary sectors and bridging disparities in access to health information.

Importantly, there appears to be a global appetite for simple infographics such as the one we piloted. We received direct requests from readers in multiple countries for non-English language versions, as well as offers from international healthcare professionals and students to assist with these translations. We formed an organized coalition of providers, translators, peer reviewers and dedicated illustrators to assist with the production of versions in nearly 20 languages. Each of our translators, many of them dedicated providers and advocates for diverse communities domestically and abroad—has disseminated our infographic with a breadth and speed made possible through the networks of social media and the digitally portable nature of a simple visual. Our Haitian-Creole version has been disseminated to patient communities in Haiti, and our Spanish version was utilized in a Spanish-language news broadcast targeting the working-class, Spanish-speaking communities of Los Angeles and San Diego. Such experiences fuel our hope that this developing multilingual library—made possible through the unprecedented connectedness afforded by social media—will serve to further close linguistic barriers that alienate patient communities amidst the English-dominated flow of COVID-19-related literature released each day.

We have combined medical expertise and creative communication to create a validated, accessible and simple public education tool about COVID-19. As our understanding of this disease continues to evolve, it will be important to clearly identify the areas of uncertainty in order to mitigate the propagation of misinformation and to reflect new evidence in revisions published in all available languages. In the weeks and months to come, we hope to translate the insights from audience feedback and serial revisions into experience-based recommendations on the design, communication and continual improvement of online visual resources in times of public health crises.

Conclusions: a new role for creative communication

As Dr. Danielle Ofri expressed in the inaugural article for this section of the journal, ‘[a]rts and humanities have the potential to serve as a bridge to connect the population and the individual’.6 The humanities offer a creative medium in the field of public health, which calls for the unconventional integration of seemingly disparate factors of disease—from the microbiology of epidemics to the complex sociopolitical fabric that shapes health on a population level. The visual arts offer an untapped trove of tools to not only reimagine critical issues, such as patient education and global dissemination of public health information, but also engage in important questions about responsible stewardship of graphic data amidst a modern social media landscape that is increasingly uncensored, rapid and visual.

COVID-19 has not only caused great human suffering but also shed light on a rapidly evolving information ecosystem that demands creative solutions for equitable, accessible public health communication. Amidst this chaos has emerged a unique role for providers—one combining the identities of physician, translator and information liaison, as well as advocate within the broader public health arena. With this new responsibility comes a fresh canvas to engage the power of visual language as a valuable and versatile currency to facilitate public health advocacy, close critical health literacy gaps and inspire socially responsible action among all patient communities.

Acknowledgements

RH, SN and DJM have no additional contributors, prior presentations of this work or conflicts of interests or disclosures to report.

Ryoko Hamaguchi, Medical Student

Saman Nematollahi, Fellow

Daniel J. Minter, Resident Physician

Funding

This work was supported by no additional funding sources.

Conflict of interest

RH, SN and DJM have no conflicts of interests to report.

References

- 1. Merchant RM, Lurie N. Social media and emergency preparedness in response to novel coronavirus. JAMA Published online March 23 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Center for Education Statistics PIAAC Results. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/piaac/current_results.asp26 March 2020, date last accessed.

- 3. National Center for Education Statistics PIAAC Proficiency Levels for Literacy. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/piaac/litproficiencylevel.asp26 March 2020, date last accessed.

- 4. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(15):458–64. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark RC, Mayer RE. Chapter 32: using rich media wisely In: Dempsey JV, Reiser RA (eds). Trends and Issues in Instructional Design and Technology, 3rd edn. London, United Kingdom: Pearson Education, Inc., 2012, 309–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ofri D. Public health and the muse. J Public Health 2008;30(2):205–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]