I. INTRODUCTION

During the 1918 flu pandemic, ‘American Indians experienced a disease specific mortality rate of four times that of other ethnic groups’, whereas during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic American Indian and Alaska Natives’ mortality rate from H1N1 was four times that of all other racial and ethnic minority populations combined.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, although Native Americans are only 11% of the population in New Mexico, they account for nearly 37% of the COVID-19 infections and 26% of the deaths.2 Racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately impacted during pandemics, not due to any biological difference between races, but rather as a result of social factors.3

In fact, Blumenshine et al. hypothesized in 2008 that racial and ethnic disparities in infection and death during pandemics were due to three factors: disparities in exposure to the virus; disparities in susceptibility to contracting the virus; and disparities in treatment.4 Specifically, racial and ethnic minorities face increased risk of exposure because they work in low wage jobs that do not provide the option to work at home and they cannot afford to miss work even when they are sick. They also experience increased risk of susceptibility to pandemics because of preexisting health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease. Finally, racial and ethnic minorities report lacking access to a regular source of healthcare as well as appropriate treatment during pandemics, causing disparities in treatment.

When the 2009 H1N1 pandemic occurred, a group of researchers empirically showed that Blumenshine’s factors were associated with racial and ethnic minorities increased hospitalization and death from H1N1.5 Racial and ethnic minorities were unable to stay at home, suffered from health conditions that were risk factors for H1N1, and lacked access to healthcare for treatment, which increased their H1N1 infection and death rates as evidenced by health and survey data.6 For instance, health data from Boston and Chicago showed that African Americans and Latinos were overrepresented among hospitalizations for H1N1; whereas in Oklahoma, rates for African Americans were 55% compared to 37% for Native Americans and 26% of whites.7 In California, Latinos were twice as likely to be hospitalized and die from H1N1 compared to whites.8 In Texas, Latinos accounted for only 37% of the population, but represented 52% of H1N1 deaths in the first 6 months of the pandemic. A national survey showed that racial and ethnic minorities were unable to practice social distancing or stay at home during the H1N1 pandemic because they could not work at home and lacked paid sick leave or access to healthcare.9

Unsurprisingly, these racial and ethnic disparities are being replicated in COVID-19 infections and death rates. African Americans make up just 12% of the population in Washtenaw County, Michigan but have suffered a staggering 46% of COVID-19 infections.10 In Chicago, Illinois, African Americans account for 29% of population, but have suffered 70% of COVID-19 related deaths of those whose ethnicity is known.11 In Washington, Latinos represent 13% of the population, but account for 31% of the COVID-19 cases, whereas in Iowa Latinos comprise are 6% of the population but 20% of COVID-19 infections.12 The African American COVID-19 death rates are higher than their percentage of the population in racially segregated cities and states including Milwaukee, Wisconsin (66% of deaths, 41% of population),13 Illinois (43% of deaths, 28% of infections, 15% of population),14 and Louisiana (46% of deaths, 36% of population).15 These racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infections and deaths are a result of historical and current practices of racism that cause disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and treatment.

There are three different levels of racism: institutional, interpersonal, and structural. Institutional racism operates through ‘neutral’ organizational practices and policies that limit racial and ethnic minorities equal access to opportunity. Interpersonal racism operates through individual interactions, where an individual’s conscious and/or unconscious prejudice limits racial and ethnic minorities’ access to resources.16 Structural racism operates at a societal level and refers to the way laws are written or enforced, which advantages the majority, and disadvantages racial and ethnic minorities in access to opportunity and resources.17 In this article, we focus on historical and current practices of structural racism that cause disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, we discuss how structural racism in employment causes disparities in exposure; structural racism in housing causes disparities in susceptibility; and structural racism in healthcare causes disparities in treatment.

This article proceeds as follows: first we examine how gaps in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act have resulted in disparate working conditions that contribute to racial and ethnic minorities’ greater exposure to COVID-19. Next, we review the gaps in Title X of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1992 and the CARES Act that leave racial and ethnic minorities without working water and vulnerable to toxins that cause respiratory illness, a risk factor for COVID-19 infections. These housing conditions make racial and ethnic minorities more susceptible to contracting COVID-19. Then, we discuss how the enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the language of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the CARES Act prevents racial and ethnic minorities from accessing quality healthcare treatment for health conditions and COVID-19. Finally, we suggest legal solutions to address structural racism as well as public health solutions to help mitigate the racialized effects of the disease.

II. COVID-19 Disparities in Exposure: Structural Racism in Employment

A recent New York Times analysis of census data crossed with the federal government’s essential workers guidelines found that ‘one in three jobs held by women has been designated as essential during this pandemic, and nonwhite women are more likely to be doing essential jobs than anyone else’.18 Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that African Americans account for 30% of all licensed practical and vocational nurses, whereas Latinos account for 53% of all agricultural workers, jobs deemed ‘essential’ during the COVID-19 pandemic.19 Consequently, many racial and ethnic minorities are unable to shelter at home and socially distance themselves in part because they are employed in ‘essential jobs’ that require them to interact with others, increasing racial and ethnic minorities’ exposure to COVID-19.

Racial and ethnic minorities’ disparities in exposure to COVID-19 are due in part to structural racism in employment. During the Jim Crow era (1875–1968), employment laws were enacted that provided protections for white workers and disadvantaged racial and ethnic minorities. For example, many laws that expanded collective bargaining rights either explicitly excluded racial and ethnic minorities, or allowed unions to discriminate against racial and ethnic minorities.20 These employment laws benefited whites by providing them access to unions that bargained for paid sick leave. However, it left racial and ethnic minority workers without union representation and paid sick leave, forcing them to go to work even when they were sick and increasing disparities in their exposure to pandemic viruses, like COVID-19. Although the Jim Crow Era ended in 1968, many racial and ethnic minorities still do not have paid sick leave21 and other employment laws still limit racial and ethnic minorities’ access to equal pay, which causes disparities in exposure to COVID-19. The plight of agricultural workers and home healthcare workers are illustrative of this point.

Agricultural workers tend to be immigrants from countries such as Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean who work in 42 of the 50 states, including California, Illinois, Texas, and Washington.22 Almost a third of agricultural workers have incomes below the poverty level and do not have paid sick leave. This is because agricultural workers are not fully covered by the FLSA of 1938.23 The FLSA limited the work week to 40 h and established federal minimum wage and overtime requirements, but exempted from these protections domestic, agricultural, and service workers, who are predominately racial and ethnic minorities.24 In 1966, the minimum wage requirements were applied to ‘most’ agricultural workers, yet the workers still do not receive overtime and are paid 50 cents less than the minimum wage.25 Also, instead of the minimum wage, some workers are still paid based on each piece of food they pick.26 The failure to provide agricultural workers with higher wages and overtime pay is due to structural racism. The initial failure to cover these workers under the FLSA benefited white workers by boosting their wages, while limiting the wages of immigrants. The current lack of protections under the FLSA benefit white farmers by limiting their employee costs, while harming minority workers that cannot afford to miss work even when they are sick. Minority workers forced to work even when they are sick increases the risk of exposure to viruses for all agricultural workers because they work in close quarters.

Home healthcare workers, who are considered domestic workers, are also left unprotected. Two-thirds of home healthcare workers are women of color.27 Although the Medicaid program28 primarily funds home healthcare workers, the wages of these workers are so low that one in five (20%) homecare workers are living below the federal poverty line, compared to 7% of all US workers, and more than half rely on some form of public assistance including food stamps and Medicaid.29 They also do not have paid sick leave. Even though the Department of Labor (DOL) issued regulations in 2015 that for the first time made the FLSA apply to ‘most’ home healthcare workers,30 many workers still remain unprotected. The DOL under the Trump Administration has issued guidance suggesting that home healthcare workers employed by home healthcare companies, also referred to as nurse or caregiver registries, are independent contractors.31 This is significant because the FLSA does not cover independent contractors. These practices have disadvantaged home healthcare workers by limiting their wages and access to paid sick leave.

The failure to provide home healthcare workers with higher wages and paid sick leave is due to structural racism. The initial failure to cover these workers under the FLSA benefited white workers by boosting their wages, while limiting the wages of racial and ethnic minorities, particularly women of color. Seventy-seven years later, when most home healthcare workers were finally covered by the FLSA, companies began classifying them as independent contractors. This benefits home healthcare companies by lowering employment costs because among other things companies then do not have to pay workers minimum wage or overtime pay. As a result of low wages and lack of paid sick leave, home healthcare workers must continue to work in close proximity to patients that are often vulnerable to COVID-19, increasing home healthcare workers exposures to COVID-19.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many low-wage workers32 have been deemed as ‘essential’ including agricultural workers33 and homecare workers, yet they do not have adequate wages or personal protective gear.34 The federal government is also currently seeking to lower the wages of immigrant agriculture workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, at the same time it is increasing visa approvals to ensure that US farmers have enough immigrant workers for spring planting.35 Additionally, unlike healthcare workers providing care in institutional settings, homecare workers have not been provided with masks. In fact, one worker said ‘she had been making protective masks out of paper towels’ and ‘hand sanitizers out of supplies she bought herself’.36

The CARES Act,37 the largest economic relief bill in US history, has approved $2.2 trillion to help businesses and individuals affected by the pandemic and economic downturn, giving workers health coverage for COVID-19, increased unemployment benefits, and paid sick leave.38 But the CARES Act does not cover most agricultural workers and home healthcare workers. Because roughly 50% of agriculture workers are undocumented immigrants, employment relief or the expanded healthcare protections provided by the CARES Act does not cover them.39 Homecare workers are also not covered by the CARES Act because homecare industry advocates argued that there would be a worker shortage if home health workers were included.40 Thus, the CARES Act is an example of structural racism because it primarily advantages white workers, while disadvantaging racial and ethnic minorities who do not receive the protections of the CARES Act.

As illustrated by the treatment of agricultural and home healthcare workers, structural racism increases racial and ethnic minorities’ exposure to the COVID-19 virus. Neither the employment laws, nor the CARES Act, ensure that racial and ethnic minority workers receive minimum wage and access to paid sick leave. Consequently, these workers, many of whom have been deemed ‘essential workers’, cannot stay at home, increasing their exposure to COIVD-19. Racial and ethnic minorities also experience increased susceptibility to contracting COVID-19 because of poor housing conditions resulting from structural racism.

III. Disparities in Susceptibility to Contracting COVID-19: Structural Racism in Housing

Racial and ethnic minorities are more susceptible to contracting viruses because of residential segregation due to structural racism. The federal government created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1933, which subsidized housing builders as long as none of the homes were sold to African Americans, a practice that was called redlining.41 The FHA also published an underwriting manual that stated that housing loans to African Americans would not be insured by the federal government. The FHA policies, examples of structural racism, advantaged whites seeking to buy homes by creating the suburbs, while relegating African Americans to racially segregated neighborhoods. Racially segregated neighborhoods that are predominately African American usually have less economic investment and fewer resources, such as places to exercise or play, which is associated with higher rates of cardiovascular disease risk for African American women.42 These neighborhoods also have more pollution, noise, and overcrowded housing stock associated with asthma, obesity, and cardiovascular disease,43 which increase the susceptibility of contracting COVID-19.44

In 1992, the federal government enacted Title X of the of the Housing and Community Development Act authorizing the federal government to provide grants to reduce lead paint hazards in nonfederal housing. This is the only federal housing law addressing housing-related health hazards, even though decades of research has shown that racially segregated African American neighborhoods have ‘poorer housing stock and code violations for asbestos, mold and cockroaches’, which has been linked to increased rates of respiratory illness, such as asthma.45Hence, it is unsurprising that housing in racially segregated neighborhoods is more likely to have severe health-related housing violations, increasing racial and ethnic minorities’ exposure to hazards that increase susceptibility to COVID-19.46

Examples of severe health-related housing violations include: “plumbing that does not have hot and cold water; a flushing toilet, and a bathtub or shower; kitchen facilities that do not have a sink with a faucet; a stove or range oven and a refrigerator; and more than 1.5 persons per room (i.e. 4 people living in an apartment with only two total rooms).”47 African American and Latinx households are almost twice as likely to ‘lack complete plumbing than white households, and Native American households are 19 times more likely to lack complete plumbing’.48 Without plumbing, racial and ethnic minorities cannot wash their hands or bodies to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

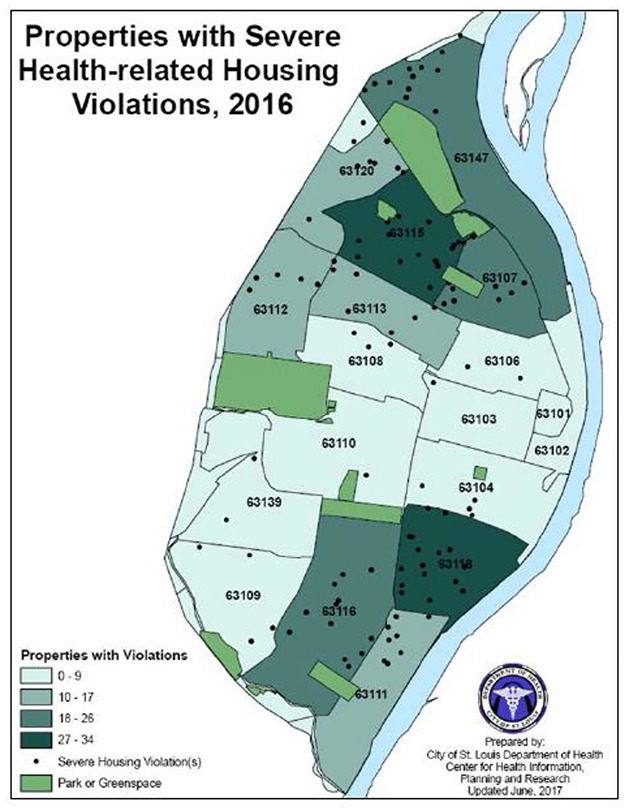

Some specific data linking housing to COVID-19 data is illustrative. In St Louis, Missouri, African Americans account for 69% of COVID-19 infections and only 49% of the population.49In Missouri, the predominately African American area of St Louis city had the most housing units with one or more severe health related housing violations (41.5%), compared to St Louis County, a predominately white area (30%), Missouri (29.6%), and the USA (35.6%). More specifically, as shown in Figure 1, housing properties located in St Louis city zip code 63115 ranked in the highest quartile of violations and had one of the highest percentages of families living in poverty. Not surprisingly, this is the zip code with the most cases of COVID-19 infections in St Louis city.

Figure 1.

St Louis Severe Health Related Housing Violations. St Louis Department of Health, St Louis. Community Health Status Assessment, 2017. This image is not covered by the terms of the Creative Commons license of this publication. For permission to reuse, please contact the rights holder.

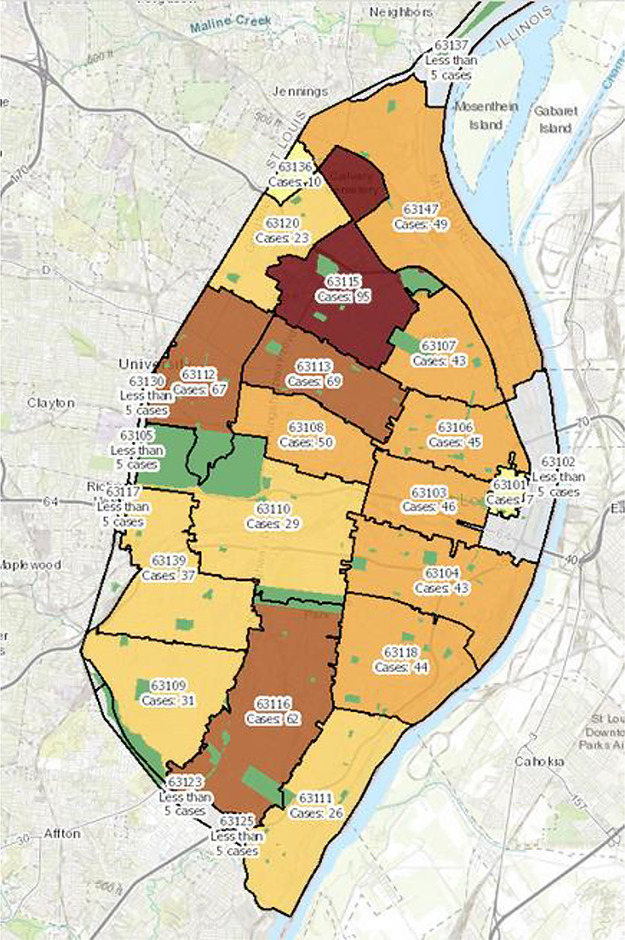

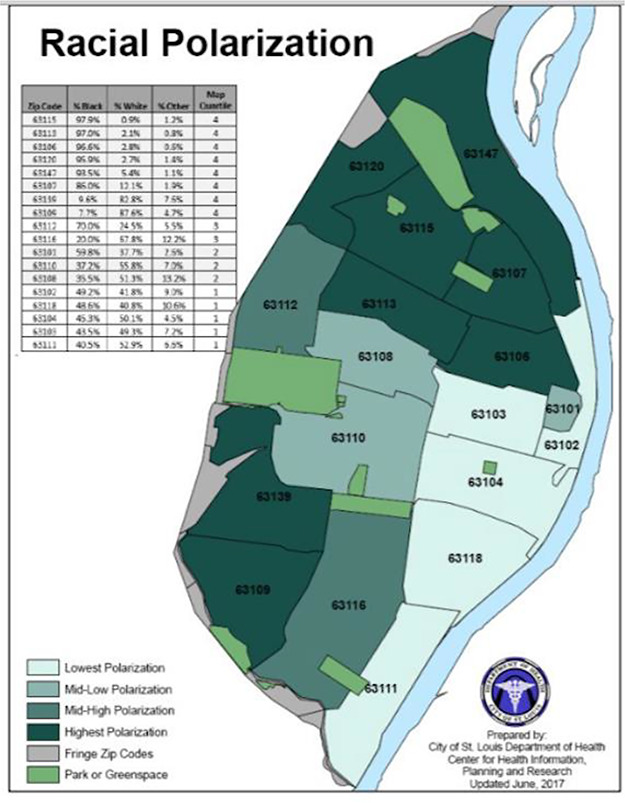

Demonstrated by Figure 2, COVID-19 infection rates in St Louis are highest in predominately African American neighborhoods. As of April 19, 2020, there were 95 cases of COVID-19 in zip code 63115,50 which as mentioned above has the highest rates of severe health-related housing violations. This zip code is also extremely racially segregated. Shown in Figure 3, 98% of the population in zip code 63115 is African American, 1% white, and 1% other.51 This is also true for zip code 63113, with the second highest cases of COVID-19 infection, 69. About 97% of the population is African American, 2% white, and 1% other.

Figure 2.

St Louis COVID-19 Infections as of April 19, 2020. St Louis COVID-19 Infections. St Louis Department of Health, St Louis City Department of Health COVID-19 website, 2019. This image is not covered by the terms of the Creative Commons license of this publication. For permission to reuse, please contact the rights holder.

Figure 3.

St Louis Racial Segregation. St Louis Racial Polarization. St Louis Department of Health, St Louis Community Health Status Assessment, 2017. This image is not covered by the terms of the Creative Commons license of this publication. For permission to reuse, please contact the rights holder.

These problems are not limited to St Louis. In Michigan, African Americans account for 33% of all COVID-19 infections and 41% of the deaths, although they represent only 14% of the population.52 In Detroit, COVID-19 deaths have reached 538 in part because of housing factors. The city has poor air quality and prior to the pandemic, many homes did not have water, inhibiting residents from washing their hands.53 Although the Detroit mayor has worked with the water department to restore water for $25 a month, this is not a viable solution in a city where many of the workers have lost their jobs, so they cannot afford to turn the water back on.54 Without water, they cannot wash their hands or body to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Although the CARES Act created a federal moratorium on evictions for federally assisted housing and federally backed mortgages, it does not address health-related housing violations such as access to clean water, leaving racial and ethnic minorities more susceptible to COVID-19 infection because they are unable to wash their hands.55 Thus, the lack of federal law addressing housing-related health hazards is an example of structural racism. The lack of law advantages landlords who make money renting these apartments, while disadvantaging racial and ethnic minorities who are forced to live in buildings with health violations. Living in housing with severe health-related housing violations, such as access to water, increases racial and ethnic minorities’ susceptibility to COVID-19 because they cannot wash their hands or body to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Racial and ethnic minorities also do not have access to quality healthcare, which increases disparities in treatment for COVID-19.

IV. COVID-19 Disparities in Treatment: Structural Racism in Healthcare

Disparities in treatment are a result of structural racism during the Jim Crow era, which continues today. In 1946, the federal government enacted the Hill-Burton Act to provide funding for the construction of public healthcare facilities.56 Although the Act mandated that adequate healthcare facilities be made available to all state residents regardless of race, it allowed states to construct racially separate and unequal facilities. The Hill Burton Act used racial and ethnic minorities’ tax money for the construction of healthcare facilities that provided care to whites, but barred racial and ethnic minorities from receiving care. Lacking access to care, African Americans have higher rates of untreated respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease, which are risk factors for COVID-19.57 Even though Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed to equalize access to quality healthcare for all races, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has not applied Title VI to hospital closures linked to race58 or physician treatment decisions based on race.59 Additionally, laws banning immigrants from accessing healthcare benefits under the Patient Protection and ACA and the CARES Act, limit racial and ethnic minorities access to healthcare. As a result, racial and ethnic minorities lack access to treatment for COVID-19 and other health conditions.60

In 2006, Sager and Socolar reported that, as the African American population in a neighborhood increased, the closure and relocation of hospital services increased for every period from 1980 to 2003, except between 1990 and 1997.61 These findings were shown again in 2009, 2011, 2012, and 2014.62 As a result of these closures, African Americans’ access to healthcare is limited. As hospitals closed in predominately African American neighborhoods, physicians connected to the hospitals left the area and the remaining hospitals’ resources were strained, causing the care provided to gradually deteriorate.63 Research shows that hospital closures decreased beds in African American neighborhoods, while increasing beds in white neighborhoods where the hospitals reopened.64 Thus, the failure to regulate hospital closures under Title VI even though they have been linked to race is an example of structural racism. The hospital closures have benefited white communities by increasing access to healthcare, while harming African American communities by limiting access to healthcare.

Racial and ethnic minorities have also long been subject to interpersonal racism and poor treatment by healthcare providers because of structural racism. One study revealed that ‘69 percent of medical students surveyed exhibited implicit preferences for white people’ and ‘other studies have found that physicians tend to rate African American patients more negatively than whites on a number of registers, including intelligence, compliance, and propensity to engage in high-risk health behaviors’.65 African Americans often sense this interpersonal racism against them, which results in delays seeking care, an interruption in continuity of care, nonadherence, mistrust, reduced health status, and avoidance of the healthcare system.66

When African Americans do seek care, they receive poorer quality of care than whites. According to a study conducted by Harvard researchers, African American Medicare patients received poorer basic care than Caucasians who were treated for the same illnesses.67 The study showed that only 32% of African American pneumonia patients with Medicare were given antibiotics within six hours of admission, compared with 53% of other pneumonia patients with Medicare.68 Also, African Americans with pneumonia were less likely to have blood cultures done during the first two days of hospitalization 69 Other studies have shown that lower death rates are associated with prompt administration of antibiotics and collection of blood cultures. 70 Yet, these life-saving therapies are often withheld from elderly African Americans. This is an example of structural racism. Because HHS does not apply Title VI to healthcare providers, physicians are allowed to limit African Americans’ access to quality healthcare based on interpersonal racism. This benefits whites receiving quality care, while harming African Americans left without access to quality healthcare.

Structural racism also prevents other racial and ethnic minorities from accessing healthcare services. Agricultural workers who are primarily immigrants do not have health insurance and are poor, thus they forgo healthcare.71 Additionally, other undocumented immigrants in the USA, most of whom originally hail from Mexico, Central America or Asia, do not have access to healthcare under the ACA.72 Moreover, regardless of whether immigrants are documented or not they often forgo care because of punitive immigration policies,73 such as increased Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) enforcement.74 This is an example of structural racism. The government and employers save money by not providing health insurance, while immigrants are harmed because it limits their access to healthcare. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to quality healthcare have continued during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the CARES Act provides Medicaid coverage for COVID-19 related testing and treatment, it has not addressed racial and ethnic disparities in access to healthcare.75 As discussed above, the healthcare provisions of CARES Act do not cover many essential workers, who are racial and ethnic minorities. Furthermore, racial and ethnic minorities lack access to COVID-19 tests and testing sites. For example, lack of access to healthcare services is having a deadly impact on African Americans in St Louis. In St Louis, as of April 20, 2020, all but three deaths from COVID-19 have been African Americans.76 The zip code with the most cases of COVID-19 viruses in St Louis city (63115) is predominately African American (98%) and currently lacks a public testing site for COVID-19.77 Research shows that by 2010 St Louis only had one hospital in a predominately African American neighborhood, compared to 18 in the 1970s.78 Because of these hospital closures, St Louis only has one hospital in a predominately African neighborhood to treat those infected with COVID-19.79

There have also been numerous reports of African Americans seeking testing and treatment for COVID-19, who have been turned away.80 Unfortunately, some of those turned away have died.81 Throughout this article, we have highlighted how structural racism has caused racial and ethnic disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and treatment of COVID-19. The last section provides suggests for addressing structural racism as well as public health solutions to help mitigate the racialized effects of the disease.

V. Legal and Public Health Solutions

A study in 2008 predicted that racial and ethnic disparities in work place protections, housing, and access to healthcare and other structural factors would make it difficult for minority populations to follow mitigation efforts such as social distancing.82 The 2009 H1N1 pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic have shown that these predictions are true. Without legal protections and public health plans, racial and ethnic minorities are more exposed, susceptible, and more likely to suffer and die during pandemics. The main purpose of this article was to describe how this has actually occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. We must take steps to provide legal protections and public health plans that address the specific needs of racial and ethnic minorities. Below we highlight some areas we believe should be priorities to address structural racism. This is not a comprehensive list. Rather, we identify some tangible approaches that may help ensure the same inequities in the next disaster or outbreak.

A. Addressing Structural Racism: Short and Long Term Legal Solutions

At a minimum, government plays a big role in implementing short-term and long-term solutions to address structural racism by changing the employment, housing, and healthcare laws.

Currently, some states are trying to provide some short-term solutions for low-wage workers by providing extra compensation. For example, California is providing financial support for undocumented immigrants affected by this pandemic, although some governors sought and received Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approval to give homecare workers additional pay.

In particular, the Arkansas governor received approval from CMS to use some CARES Act funding to provide payments to direct care workers.83 Eligible workers, all direct care workers except those working in nursing homes and hospitals,84 will receive a bonus of $125 per week for part-time workers (20–39 h) and $250 per week for full-time workers (40 or more hours).85 If the worker is employed in a facility ‘where someone has tested positive for COVID-19, they will get an additional $125 a week for working one to 19 hours a week, $250 for those working 20 to 39 hours and $500 a week for those working 40 hours or more’.86 The payments will be retroactive to April 5 and will continue until at least May 30.87

The New Hampshire governor has also decided to use some of the CARES Act funding to provide direct care workers and others working in Medicaid-funded residential facilities, with weekly $300 payments for working during the COVID-19 pandemic until the end of June.88 Twelve states and the District of Columbia have already passed laws to increase wages for direct care workers above the set Medicaid rate before the COVID-19 pandemic,89 which they could use to increase the wages of homecare workers. Other states should use the examples set by Arkansas and New Hampshire and seek CMS approval to use CARES Act funding to increase the wages of homecare workers.

Although admirable, these are not the universal solutions. It may be time to consider that all workers deemed as essential should receive a guaranteed basic minimum income and paid sick leave until the end of the pandemic, i.e. the last confirmed death from COVID-19.90 Providing essential workers with a guaranteed basic minimum income and paid sick leave would allow sick workers to stay at home decreasing disparities in exposure to COVID-19 for racial and ethnic minorities who often cannot afford to stay home when they are sick. Additionally, low-wage workers, who are primarily racial and ethnic minorities, should receive savings accounts to help equalize their pay compared to white workers that have benefitted from employment law protections. These benefits should also include survivorship benefits for essential workers without life insurance to ensure that upon their death, their families can still survive.

The ideas of a guaranteed basic minimum income and paid sick leave are not new. In 1976, Alaska implemented a guaranteed basic income called the Alaska Permanent Fund and has been sending dividends to every Alaskan resident since 1982. 91 Thus, for almost 20 years Alaska has provided guaranteed support for residents, helping to address poverty, with no change in full-time employment. In 2010, 2011, and 2012, researchers studying racial and ethnic disparities in hospitalization and death rates from H1N1 noted that the best way to decrease disparities in exposure to H1N1 was to provide low-wage workers with paid sick leave.92 Specifically, they noted that the USA needs comprehensive ‘paid sick-leave legislation that enables low-income and private-sector workers to adhere to social-distancing recommendations even when they lack paid sick leave’. These short-term policies can be added to the next round of COVID-19 relief legislation. In terms of long-term solutions to address structural racism in employment and disparities in exposure to viruses, the FLSA should apply to all domestic, agricultural, and service workers, even if they are deemed as independent contractors. Moreover, these workers should have paid sick leave and a guaranteed basic income that ensures that workers are above the poverty level.

To address structural racism in housing and disparities in susceptibility, the federal government needs to enact legislation to address health-related housing violations. In 2020, there is no reason why all those residing in the USA should not have access to clean running water; plumbing with hot and cold water; a flushing toilet, and a bathtub or shower; and kitchen facilities that includes a sink with a faucet, a stove or range oven, and a refrigerator. In the short-term, the state and local governments need to proactively use existing law to address health related housing violations, such as access to water. In the long term, state and federal governments need to enact laws and provide grants to ensure that all housing has access to clean running water; plumbing with hot and cold water; a flushing toilet, and a bathtub or shower; and kitchen facilities that includes a sink with a faucet, a stove or range oven, and a refrigerator. In addition, the next round of COVID-19 relief legislation should include language that mandates access to clean water (bottled or tap) for residents in the areas most affected by COVID-19, which will decrease disparities in susceptibility to the virus by stopping the spread.

In order to address disparities in treatment and structural racism that limits racial and ethnic minorities’ access to healthcare, the federal government must provide low cost or free expanded healthcare options for undocumented immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities who live in states that did not expand Medicaid. As a short-term solution, in the next round of COIVD-19 relief, all essential workers should be granted access to healthcare for treatment of COVID-19 and any other health ailments without fear of ICE enforcement. Moreover, as a long-term solution, the federal government needs to fully enforce Title VI by holding hospitals and healthcare providers responsible for racism, which increases racial and ethnic disparities in treatment.

B. Public Health Mitigation of Health Inequities

The inequities we are seeing in this pandemic are predictable, and the US has failed to plan properly to protect racial and ethnic minority populations. Health researchers have long predicted that existing inequities would worsen a pandemic.93 Had their recommendations and similar advice by other researchers in past pandemics been taken, perhaps the inequities we described above due to COVID-19 would not have been so vast. For example, detailed race/ethnicity reporting related to virus hospitalization and deaths and ‘targeted, culturally appropriate risk communication, using trusted spokespersons and channels’ that engages ‘both national and local organizations that represent minority populations …to get the message to at-risk groups’ 94 could help with COVID-19 spread.

Although, jurisdictions are just beginning to collect racialized data concerning COVID-19 infections and deaths, there needs to be a better developed public health action plan on how to use the data that is being collected to address disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and treatment. Additionally, healthcare providers need to be educated to ensure ‘that they recognize higher-risk individuals and aggressively deliver adequate care to them’.95 Ruha Benjamin notes ‘a “lack of trust” on the part of Black patients is not the problem with the healthcare system; rather “it is a lack of trustworthiness” by the healthcare system and medical industry’.96

In this piece, we highlight some structural problems causing the increased death and illness of minority populations of COVD-19. At a minimum, for health justice for these communities, minority groups, and minority-led organizations need to be engaged about how to develop fair allocation policies for testing, PPE, ventilators, clinical trial enrollment, future treatment, and vaccine access.

African Americans and other minority populations are bearing the brunt of COVID-19. As such, they should have access to treatments and vaccines that will hopefully be developed for COVID-19 and policies that take into account should be developed in this regard. This will help rebuild trust and understanding. It may be important to focus on ‘local and state health departments, federally qualified health centers, and other healthcare providers …partner …with community-based organizations that serve at-risk populations’.97 This would help those without healthcare coverage, including undocumented immigrants, to seek care. Each of the suggestions noted above were made in some form by Quinn et al. in 2011 during the H1N1 pandemic. We do not attempt an all-encompassing list here but we urge engagement with the past literature from pandemics and racial equity, many articles that are linked here. The COVID-19 pandemic is proving to be a more serious public health threat than H1NI, so it is time to adopt these changes to current public health plans.98

These are not easy solutions, but they are vital to prevent further unnecessary COVID-19 infection and deaths by racial and ethnic minorities. They require government investment and commitment. However, it is only through such support that we can end the cycle of racial and ethnic inequity that this nation faces, not only during this pandemic, but in future disasters and pandemics. We have outlined some legal and policy measures that should be addressed. However, to achieve true health justice for all, interventions to address the root causes of inequity, including all community conditions through one’s life course are necessary.

Footnotes

Dennis Andrulis, et al., H1N1 Influenza Pandemic and Racially and Ethnically Diverse Communities in the United States: Assessing the Evidence of and Charting Opportunities for Advancing Health Equity, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health p. 13 (Sept. 2012).

Kate Stafford, et al., Racial toll of virus grows even starker as more data emerges, Associated Press, https://apnews.com/8a3430dd37e7c44290c7621f5af96d6b (accessed Apr. 18, 2020) Stafford, et al., supra note 3.

Seema Mohapatra & Lindsay F. Wiley, Feminist Perspectives in Health Law, 47 J. L., Med. Ethics, 47 S2, 103 (2019); Rachel Rebouche and Scott Burris, “The Social Determinants of Health”, in Oxford Handbook of U.S. Health Law 1097–1112 (I. Glenn Cohen et al., eds., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017: 1097–1112); Dorothy Roberts, Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, And Big Business Re-Create Race In The Twenty-First Century 23–25 (2011) (Roberts is critical of “the delusion that race is a biological inheritance rather than a political relationship”).

Philip Blumenshine et al., Pandemic Influenza Planning in the United States from a Health Disparities Perspective, 14(5) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, no. 5709–15, (May 2008): 709–15, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071301.;Robert J. Blendon, et al., Public Response to Community Mitigation Measures for Pandemic Influenza, 14 (5) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, no. 5778–86, (May 2008): 778–86, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071437.; Sandra Crouse Quinn et al., Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Healthcare in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic, Am. J. Public Health 101, no. 2285–93 (Feb. 2011), 285–93, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029.

Sandra Crouse Quinn et al., Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Healthcare in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic, Am. J. Public Health 101, no. 2285–93 (Feb. 2011), 285–93, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029.

Id.

Sandra Crouse Quinn et al. Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Healthcare in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic, Am. J. Public Health 101, no. 2285–93 (Feb. 2011), 285–93, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029.

Monica Schoch-Spana, et al., Stigma, Health Disparities, and the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic: How to Protect Latino Farmworkers in Future Health Emergencies, Biosecur. Bioterror. 8(3): 243–253 (2010).

Sandra Crouse Quinn et al., Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Healthcare in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic, Am. J. Public Health 101, no. 2285–93 (Feb. 2011), 285–93, available at: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029; Supriya Kumar, et al., The Impact of Workplace Policies and Other Social Factors on Self-Reported Influenza-Like Illness Incidence During the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic, 102 (1) Am. J. Pub. Health (Jan. 2012): 132–140.

Kate Stafford, et al., Racial toll of virus grows even starker as more data emerges, Associated Press, https://apnews.com/8a3430dd37e7c44290c7621f5af96d6b (accessed Apr. 18, 2020).

Elliot Ramos & Maria Ines Zamudio, In Chicago, 70% of Cases COVID-19 Deaths Are Black, Chicago NPR—WBEZ, https://www.wbez.org/stories/in-chicago-70-of-covid-19-deaths-are-black/dd3f295f-445e-4e38-b37f-a1503782b507 (accessed Apr. 5, 2020).

Miriam Jordan and Richard Oppel Jr, For Latinos and Covid-19, Doctors Are Seeing an ‘Alarming’ Disparity, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/us/coronavirus-latinos-disparity.html (accessed May 9, 2020).

Teran Powell, Milwaukee’s Covid-19 spread highlights the disparities between white and blacks, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/14/milwaukees-covid-19-spread-highlights-the-disparities-between-white-and-black (accessed Apr. 14, 2020).

Jerry Nowicki, COVID-19 shows racial health disparities in Illinois, The Southern Illinoisan, https://thesouthern.com/news/local/state-and-regional/covid-19-shows-racial-health-disparities-in-illinois/article_14a890fc-9d2b-5b09-8198-5ed14774fbd8.html (accessed Apr. 11, 2020).

CDC, Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Diseases: Weekly States-Specific Data Updates by Select Demographic and Geographic Characteristics, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid_weekly/ (accessed Apr. 14, 2020), CDC, supra note 2.

Ruqaiijah Yearby, Internalized Oppression: The Impact of Gender and Racial Bias in Employment on the Health Status of Women of Color, 49 Seton Hall Law Rev. 1037–1066 (2019).

Ruqaiijah Yearby, Structural Racism and Health Disparities: Moving Beyond the Social Determinants of Health to Achieve Racial Equity, J. Law med. Ethics (forthcoming 2020).

Campbell Robertson & Robert Gebeloff, How Millions of Women Became the Most Essential Workers in America, N.Y. Times, Apr. 18, 2020, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/18/us/coronavirus-women-essential-workers.html (accessed Apr. 18, 2020).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html (accessed May 14, 2020).

Danyelle Solomon, et al., Systematic Inequality and Economic Opportunity, The Center for American Progress (Aug. 2019), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2019/08/07/472910/systematic-inequality-economic-opportunity/ (accessed May 14, 2020).

Supriya Kumar, et al., The Impact of Workplace Policies and Other Social Factors on Self-Reported Influenza-Like Illness Incidence During the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic, 102 (1) Am. J. Pub. Health (Jan. 2012): 132–140.

Monica Schoch-Spana, et al., Stigma, Health Disparities, and the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic: How to Protect Latino Farmworkers in Future Health Emergencies, Biosecur. Bioterror. 8(3): 243–253 (2010).

Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, 29 U.S.C. §§201–19 (2020).

Id.

Autumn Canny, Lost in a Loophole: The Fair Labor Standards Act’s Exemption of Agricultural Workers for Overtime Compensation Protections, 10 Drake J. Agric. L. 355- (2005).

U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, Agricultural Employers Under the Fair Labor Standards ACT: Fact Sheet #12, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/12-flsa-agriculture (accessed May 14, 2020).

PHI, US Home Care Workers: Key Facts supra note 60 at 3 (2018).

Medicaid is a joint federal and state partnership, which the states administer. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396, 1396a(a)(1)–(2), (5) (2006 & West Supp. 2018).

PHI, US Home Care Workers: Key Facts supra note 60 at 5–6 (2018).

80 F.R. 55029–30 (Sept. 14, 2015).

Wage and Hour Division, U.S. Department of Labor, Field Assistance Bulletin No. 2018–4 (Jul. 13, 2018); Labor and Employment Group of Ballard Spahr, LLP, Labor Classification in the Home Healthcare Industry: A sign of What’s to Come? (Jul. 16, 2018)

Service sector jobs, such as cashiers, waitstaff and care aides, are the poorest workers and least likely to be able to avoid viral exposure. Beatrice Jin and Andrew McGill, “Who Is Most at Risk in the Coronavirus Crisis: 24 Million of the Lowest-Income Workers.” Politico, https://politico.com/interactives/2020/coronavirus-impact-on-low-income-jobs-by-occupation-chart/ (accessed, Mar. 21, 2020), 24 million workers are low-wage workers (get paid less than $11.50 per hour). Id.

Alejandra Borunda, Farm Workers risk Coronavirus Infection to Help the US Fed, National Geographic (Apr. 10, 2020).

Christoher Ingraham, Why many ‘essential’ workers get paid so little according to experts, Washington post (Apr. 6, 20202).

Franco Ordonez, White House Seeks to Lower Farmworker Pay to Help Agricultural Industry, NPR, https://www.npr.org/2020/04/10/832076074/white-house-seeks-to-lower-farmworker-pay-to-help-agriculture-industry (accessed Apr. 10, 2020).

Andrew Donlan, ‘I Deserve to Be Respected’: Home Care Workers Make Emotional Plea for Better Treatment, Home Healthcare News (Apr. 15, 2020).

Pub. Law. No. 116–138. Tit. III (2)(b) § 3211 (b) 236 (2020) 4.

Erica Warner et al., Senate Approves $2.2 Trillion Corona Virus Bill Aimed At Slowing Economic Free Fall, Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/03/25/trump-senate-coronavirus-economic-stimulus-2-trillion/ (Mar. 25, 2020).

Alejandra Borunda, Farm workers risk Coronavirus Infection to Help the US Fed, National Geographic (Apr. 10, 2020). Borunda, supra note 54.

Andrew Donlan, ‘I Deserve to Be Respected’: Home Care Workers Make Emotional Plea for Better Treatment, Home Healthcare News (Apr. 15, 2020). supra note 74. Some homecare companies have voluntarily implemented paid sick leave, and bonus pay, but not all. Id. Thus, homecare workers, who live in poverty, do not have health insurance, and work in close contact with those most likely to contract COVID-19 without protective gear, are exempted from additional pay and paid sick leave. Id

Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law (2017).

Lee Mobley, et al., Environment, Obesity, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Low-Income Women, 30 Am. J. Prev. Med. 327, 327 (2006).

R.E. Walker et al., Disparities and Access to Healthy Food in the United States: A Review of Food Deserts Literature, Health Place 16, no. 5 (2010): 876–884, at 881; N.I. Larson, et al., Neighborhood Environments: Disparities in Access to Healthy Foods in the U.S., Am. J. Prev. Med. 36, no. 1 (2009): 74–81, at 74 (2009); L.B. Lewis et al., African Americans’ Access to Healthy Food Options in South Los Angeles Restaurants, Am. J. Public Health 95, no. 4 (2005): 668–73, at 672 I.G. Ellen et al., Neighborhood Effects on Health: Exploring the Links and Assessing the Evidence, J. Urban Aff. 23, no. 3–4 (2001): 391–408, at 393; A.V. Diez Roux, Investigating Neighborhood and Area Effects on Health, Am. J. Public Health 91, no. 11 (2001): 1783–9, at 1786.

Philip Blumenshine et al., Pandemic Influenza Planning in the United States from a Health Disparities Perspective, 14(5) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, no. 5709–15, (May 2008): 709–15, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071301

Eugene Scott, 4 Reasons Coronavirus Is Hitting Black Communities so Hard., Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/044/10/4-reasons-coronavirus-is-hitting-black-communities-so-hard/ (accessed Apr. 10, 2020); Emily Benfer, Health Justice: A Framework (and Call to Action) for the Elimination of Health Inequity and Social Injustice, 65 Am. U. L. Rev. 275, 275 (2015).; National Center for Healthy Housing, Timeline, https://nchh.org/sample-shortcodes/sample-timeline/ (accessed May 14, 2020).

St. Louis Partnership for a Health Community, et al., Community Health Status Assessment 38 (Dec. 11, 2017) supra note 14.

Id.

Dig Deep & U.S. Water Alliance, Closing The Water Access Gap In the United States: A National Plan 4 (2019), http://closethewatergap.org/ (page 4 of report).

City of St. Louis Department of Health, COVID-19 Cases by Demographic Groups, https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/covid-19/data/demographics.cfm (accessed Apr. 19, 2020); St. Louis Partnership for a Health Community, et al., Community Health Status Assessment 8 (Dec. 11, 2017).

City of St. Louis Department of Health, COVID-19 Cases by Zip Code, https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/covid-19/data/zip.cfm.supra (accessed Apr. 19, 2020), note 14.

St. Louis Partnership for a Health Community, et al., Community Health Status Assessment 9 (Dec. 11, 2017) supra note 14.

COVID-19 has already killed more Detroiters than homicides have in the past two years, Fox 2 Detroit, https://www.fox2detroit.com/news/covid-19-has-already-killed-more-detroiters-than-homicides-have-in-the-past-two-years-combined (accessed Apr. 16, 2020).

Id.

Id.

Pub. Law. No. 116–138. Tit. III (2)(b) § 3211 (b) 236 (2020) 4.

See Hospital Survey and Construction Act, 42 U.S.C. § 291e(f) (2020).

Ruqaiijah Yearby, Racial Disparities in Health Status and Access to Healthcare: The Continuation of Inequality in the United States Due to Structural Racism, 77 Am. J. L Econ. Soc. 1113, 1129–38 (2018).

See Ruqaiijah Yearby, When is a Change Going Come?: Separate and Unequal Treatment in Healthcare Fifty Years After Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 67 SMU L. Rev. 287, 324–329 (2014); Brietta R. Clark, Hospital Flight From Minority Communities: How Our Existing Civil Rights Framework Fosters Racial Inequality in Healthcare, 9 DePaul J. Healthcare L. 1023, 1033–35 (2005);

42 US § 2000d-1 (2018). Physicians receiving payments under Medicare Part B are exempted from compliance with Title VI because these payments are not defined as federal financial assistance. David Barton Smith, Healthcare Divided: Race and Healing A Nation 161–164 (1999). Thus, physicians can continue to discriminate based on race. Id.

Ruqaiijah Yearby, Breaking the Cycle of “Unequal Treatment” with Healthcare Reform: Acknowledging and Addressing the Continuation of Racial Bias, 44 Conn. L. Rev. 1281, 1288 (2012). See also David Williams and C. Collins, Racial Residential Segregation: A Fundamental Cause of Racial Disparities in Health, Public Health Rep. 116 (5), 404–416 (2001) (noting that racial residential segregation is a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health.) African Americas are disproportionately likely to undergo surgery in low-quality hospitals, which is linked to higher mortality rates for African Americans compared to Whites. Justin Dimick, et al., Black Patients More Likely Than Whites to Undergo Surgery at Low-Quality Hospitals in Segregated Regions, 32 Health Aff. 1046, 1050–1051 (2013). Research has also shown that residential segregation is associated with an increase in lung cancer mortality rates for African Americans. Awori Hayanga, Residential Segregation and Lung Cancer Mortality in The United States, 148 JAMA Surg. 37, 37 (2013). Moreover, residential segregation has been associated with increased hospital closures. See David Barton Smith, Healthcare Divided: Race and Healing a Nation 200 (1999). supra note 35 (citing David G. Whiteis, Hospital and Community Characteristics in Closures of Urban Hospitals, 1980–87, 107 Pub. Health Rep. 409–416 (1992)).

Alan Sager & Deborah Socolar, Closing Hospitals in New York State Won’t Save Money but Will Harm Access to Care 27–31 (2006), http://dcc2.bumc.bu.edu/hs/Sager Hospital Closings Short Report 20Nov06.pdf.

Michelle Ko, et al., Residential Segregation and the Survival of US Urban Public Hospitals, 7 Med. C. Res. Rev. 243 (2014); Renee Hsia, et al., System-Level Health Disparities In California Emergency Departments: Minorities And Medicaid Patients Are At Higher Risk Of Losing Their Emergency Departments, 59 Ann. Emerg. Med. 359 (2012); Renee Hsia and Yu-Chu Shen, Rising Closures Of Hospital Trauma Centers Disproportionately Burden Vulnerable Populations, 30 Health Affairs 1912 (2011); and Yu-Chu Shen, et al., Understanding The Risk Factors Of Trauma Center Closures: Do Financial Pressure And Community Characteristics Matter?, 47 Med. Care 968 (2009).

See Brietta R. Clark, Hospital Flight From Minority Communities: How Our Existing Civil Rights Framework Fosters Racial Inequality in Healthcare, 9 DePaul J. Healthcare L. 1023, 1033–35 (2005) (“Hospital closures set into motion a chain of events that threaten minority communities’ immediate and long-term access to primary care, emergency and nonemergency hospital care...”).

Id.

Kimani Paul-Emile, Patients’ Racial Preferences and the Medical Culture of Accommodation, 60 UCLA L. Rev. 462, 493 (2012)).

Janice Sabin, et al., Physicians’ Implicit and Explicit Attitudes About Race by MD Race, Ethnicity, and Gender, 20 J. Healthcare Poor Underserved 896, 907 (2009).

John Z. Ayanian et al., Quality of Care by Race and Gender for Congestive Heart Failure and Pneumonia, 37 Med. Care 1260, 1260–61, 1265 (1999).

Id. at 1265.

Id.

Id.; see also Manreet Kanwar et al., Misdiagnosis of Community-Acquired Pneumonia and Inappropriate Utilization of Antibiotics: Side Effects of the 4-h Antibiotic Administration Rule, 131 Chest 1865, 1865 (2007) (discussing the association between timely antibiotic therapy and improved health outcomes in patients with community-acquired pneumonia); Mark L. Metersky et al., Predicting Bacteremia in Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia, 169 Am. J. Respir. Critic. Care Med. 342, 342 (2004) (“[P]erformance of blood cultures on Medicare patients hospitalized with pneumonia has been associated with a lower mortality rate.”).

Monica Schoch-Spana, et al., Stigma, Health Disparities, and the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic: How to Protect Latino Farmworkers in Future Health Emergencies, Biosecur. Bioterror. 8(3): 243–253 (2010).

See Medha D. Makhlouf, Health Justice for Immigrants, 4 U. PA. J.L. Pub. Aff.235 (2019).

Wendy E. Parmet, Trump’s immigration policies will make the coronavirus pandemic worse, STAT, https://www.statnews.com/2020/03/04/immigration-policies-weaken-ability-to-fight-coronavirus/ (accessed Mar. 4, 2020).

Wendy E. Parmet, In the Age Of Coronavirus, Restrictive Immigration Policies Pose a Serious Public Health Threat, Health Aff., https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200418.472211/full/ (accessed Apr. 18, 2020). Monica Schoch-Spana, et al., Stigma, Health Disparities, and the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic: How to Protect Latino Farmworkers in Future Health Emergencies, Biosecur. Bioterror. 8(3): 243–253 (2010).

Pub. Law. No. 116–138. Tit. III (2)(b) § 3211 (b) 236 (2020) 4.

Paulina Cachero, All but 3 people who died from COIVD-19 in St. Louis, Missouri, were black, Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/all-but-three-people-who-died-from-covid-19-in-st-louis-were-black-2020-4 (accessed Apr. 12, 2020).

City of St. Louis Department of Health, COVID-19 Public testing Locations, https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/covid-19/data/test-locations.cfm (accessed Apr. 19, 2020).

Alan Sager & Deborah Socolar, Closing Hospitals in New York State Won’t Save Money but Will Harm Access to Care 30 (2006), http://dcc2.bumc.bu.edu/hs/Sager Hospital Closings Short Report 20Nov06.pdf.

Id. at 30–31.

Jasmin Barmore, 5-year-old with rare complication becomes first Michigan child to die of COVID-19, The Detroit News (Apr. 20, 2020).

Shamar Walters & David K. Li, New York City Teacher Dies From Covid-19 After She Was Denied Tests, Family Says, NBC News (Apr. 29, 2020), Detroit Man With Virus Symptoms Dies After 3 Ers Turn Him Away, Family Says: “He Was Begging For His Life”, CBS New, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-detroit-man-dead-turned-away-from-er/ (accessed Apr. 22, 2020).

Robert J. Blendon, et al., Public Response to Community Mitigation Measures for Pandemic Influenza, 14 (5) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, no. 5778–86, (May 2008): 778–86, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071437.

Elisha Morrison, CMS approves some healthcare worker bonuses, Benton Courier, https://www.bentoncourier.com/covid-19/cms-approves-some-healthcare-worker-bonuses/article_3946adc8-800c-11ea-944a-1b151690787e.html (accessed Apr. 16, 2020).

KATV, Governor announces bonus pay for some health workers: COVID-19 death toll rises to 34, https://katv.com/news/local/governor-announces-bonus-pay-for-health-workers-at-long-term-care-facilities (accessed Apr. 15, 2020). “Eligible workers include: Registered Nurses; Licensed practical nurses; Certified nurse aides; Personal care aides assisting with activities of daily living under the supervision of a nurse or therapist; Home health aides assisting with activities of daily living under the supervision of a nurse or therapist; Nursing assistive personnel; Direct care workers providing services under home and community-based waiver; Intermediate Care Facility direct care staff including those that work for a state-run Human Development Center; Assisted Living direct care staff members; Hospice service direct care workers; and Respiratory therapists.” Id.

Elisha Morrison, CMS approves some healthcare worker bonuses, Benton Courier, https://www.bentoncourier.com/covid-19/cms-approves-some-healthcare-worker-bonuses/article_3946adc8-800c-11ea-944a-1b151690787e.htmlMorrison, supra note 81 (accessed Apr. 16, 2020).

Id.

The governor will extend the payments an additional 30 days if COVID-19 cases on May 30 exceed 1000. Id.

Mia Summerson, NH moves to boost pay for long-term care workers, Sentinel Source, https://www.sentinelsource.com/news/local/nh-moves-to-boost-pay-for-long-term-care-workers/article_78db684f-a0a6-5eaf-bf0d-29caae8811b4.html (accessed Apr. 14, 2020).

The states include: Arizona, California, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Washington. Ruqaiijah Yearby, et al., State Wage Pass Through Laws for Direct Care Workers (Dec. 16, 2019), unpublished manuscript tracking state laws that increase wages for direct care workers providing care to elderly Medicaid patients as of December 1, 2019.

Kimberly Amandeo, Universal Basic Income, Pros and Cons With Examples, The Balance, https://www.thebalance.com/universal-basic-income-4160668 (accessed Dec. 13, 2019).

Michael Coren, When you give Alaskans a universal basic income, the still keep working, Quartz, https://qz.com/1205591/a-universal-basic-income-experiment-in-alaska-shows-employment-didnt-drop/ (accessed Feb. 13, 2018).

Sandra Crouse Quinn et al., Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Healthcare in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic, Am. J. Public Health 101, no. 2 (Feb. 2011), 285–93, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029;

Philip Blumenshine et al., Pandemic Influenza Planning in the United States from a Health Disparities Perspective, 14(5) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, no. 5709–15, (May 2008): 709–15, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071301.

Id.

Id.

Ruha Benjamin, Assessing Risk, Automating Racism, 366 (6464) Science 366, no. 6464421–22 (Oct. 25, 2019): 421–22.). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz3873.

Supriya Kumar, et al., The Impact of Workplace Policies and Other Social Factors on Self-Reported Influenza-Like Illness Incidence During the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic, 102 (1) Am. J. Public Health (Jan. 2012): 132–140; Sandra Crouse Quinn et al., Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Healthcare in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic, Am. J. Public Health 101, no. 2 (Feb. 2011), 285–93, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029. Monica Schoch-Spana, et al., Stigma, Health Disparities, and the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic: How to Protect Latino Farmworkers in Future Health Emergencies, Biosecur. Bioterror. 8(3): 243–253 (2010).

Legal scholars Emily Benfer and Lindsay Wiley have suggested a whole host of useful health justice strategies to “protect workers, freeze evictions and utility shut-offs, and prioritize programs that secure safe and healthy housing conditions and nutritional supports” to mitigate the harms for the particular harms of COVID-19 focusing on housing and workers. Emily Benfer & Lindsay Wiley, Health Justice Strategies To Combat COVID-19: Protecting Vulnerable Communities During A Pandemic, Health Aff., https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200319.757883/full/ (accessed Mar. 19, 2020). They note that “state and local leaders have an unprecedented opportunity to use a combination of routine and emergency powers to protect the health of low-income people who do not have the ability to shelter in place without severe consequences and who are exposed to unhealthy conditions in their homes at a much higher rate than higher income peers.” Id.