Abstract

We sought to identify barriers to hospital reporting of electronic surveillance data to local, state, and federal public health agencies and the impact on areas projected to be overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Using 2018 American Hospital Association data, we identified barriers to surveillance data reporting and combined this with data on the projected impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital capacity at the hospital referral region level.

Our results find the most common barrier was public health agencies lacked the capacity to electronically receive data, with 41.2% of all hospitals reporting it. We also identified 31 hospital referral regions in the top quartile of projected bed capacity needed for COVID-19 patients in which over half of hospitals in the area reported that the relevant public health agency was unable to receive electronic data.

Public health agencies’ inability to receive electronic data is the most prominent hospital-reported barrier to effective syndromic surveillance. This reflects the policy commitment of investing in information technology for hospitals without a concomitant investment in IT infrastructure for state and local public health agencies.

Keywords: electronic health records, public health, syndromic surveillance, pandemic, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

Effective pandemic response requires rapid, accurate information sharing between hospitals and public health agencies. To advance these capabilities, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires hospitals to electronically send health information, including lab results and syndromic surveillance data, to local, state, and federal public health agencies, usually city or state departments of health.1,2 These reporting requirements were intended to allow public health agencies to monitor and react quickly to potential infectious disease and influenza outbreaks. However, hospitals may experience technical or administrative barriers to this reporting, and electronic hospital reporting to public health agencies has been inconsistent.3 The resulting information gaps can exacerbate the public health challenges of identifying, quarantining, and contact-tracing potentially infected individuals and preclude timely response to infected areas.4

These gaps have come into sharp relief during the COVID-19 outbreak. Despite billions of dollars in federal investment in digitizing the US health care system, aggregating information such as test results and potential cases has been done in a patchwork way with data-sharing often occurring via fax or phone.5 Had electronic data-sharing been in place, hospitals could have quickly transmitted COVID-19 testing results and syndromic surveillance data to public health agencies to supplement their testing and provide greater clarity on disease prevalence and incidence.6 A 2016 survey found 79% of public health agencies report having electronic disease reporting systems, and while larger agencies illustrate greater rates of adoption, the representativeness and completeness of data within these systems was not assessed.7 Moreover, an agency’s adoption of electronic disease-reporting systems does not necessarily mean that hospitals are able to electronically submit data to the public health agency. Since public health agencies are generally located at the state or county level, there is likely significant variation across agencies in capacity to electronically receive and aggregate data from hospitals in their locale.8 Additionally, given the large jurisdictions many public health agencies serve, hospitals within the same jurisdiction are likely to vary in their capacity to report this data electronically. As a result, the agency is charged with adopting and maintaining multiple routes of data submission to cater to varying hospital abilities. Little is known regarding how well the process of hospital reporting to public health agencies functions or what the barriers to reporting are.

To address this gap, we offer the first national data on barriers hospitals face in electronic submission of health information, including lab results and syndromic surveillance, to public health agencies. We also examine variation across states and the overlap with areas where COVID-19 has been projected to overwhelm hospital bed capacity most severely.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data

We used newly available data from the 2018 American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey and IT Supplement, fielded from January 2019 to May 2019. The survey is sent annually to the CEO of every hospital in the United Sates, with a request to complete it or delegate completion to the most knowledgeable person in the organization. To achieve a high response rate, all nonrespondents receive multiple mailings and follow-up phone calls, and the response rate for 2018 was 64%. The survey includes data on hospitals use of information technology as well as hospital characteristics such as size, teaching status, location, system membership, and ownership. We analyzed responses to the question “What are some of the challenges your hospital has experienced when trying to submit health information to public health agencies to meet meaningful use requirements?” The question had 6 yes/no response options for hospitals to select from. We calculated the number of barriers reported on average as well as the proportion of hospitals reporting each of the 6 barriers.

We combined this data with hospital referral region (HRR) level data on the projected impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from the Harvard Global Health Institute, which included HRR-level data on the projected number of total COVID-19 infections, infections requiring hospitalization, infections requiring ICU beds, and projected hospital capacity necessary for COVID-19 patients.9 Projected hospital capacity needed is measured as a percentage of total hospital beds available in the HRR. Our final analytic dataset consisted of 3512 hospitals located in 302 HRRs in 50 states.

Statistical analysis

We first calculated sample statistics on the characteristics of hospitals in our sample, and the mean and standard deviation of the number of barriers to electronic public health reporting. We then calculated the proportion of hospitals reporting each of the 6 different potential barriers. For the most prevalent challenge (lack of public health agency capacity to electronically receive data), we calculated the proportion of hospitals reporting it in each state and HRR. HRRs with more than half of hospitals reporting the public health agency inability to receive electronic data were labeled “capability gap” HRRs. Next, we assessed the projected impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital capacity at the HRR level, measured by number of infections and hospital beds needed. We assumed a 40% population infection rate over 12 months9 and stratified HRRs into quartiles based on hospital bed capacity proportion needed. Top-quartile HRRs were labeled “high need” HRRs. For capability gap/high need HRRs, we aggregated impact measures to quantify total projected COVID-19 infections and average hospital bed capacity needs.

RESULTS

The mean number of barriers to electronically reporting data to public health agencies reported by hospitals in our sample was 1.14, with a standard deviation of 1.20. Most hospitals in our sample were small with fewer than 100 beds (49.5% of hospitals), nonteaching (60.7%), located in urban areas (68.3%), and privately-owned nonprofit (59.1%). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Number of Barriers and Sample Characteristics

| Sample Characteristics | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Public Health Reporting Barriers | ||

| Number of barriers to electronic public health reporting | 1.14 | 1.20 |

| Hospital Characteristics | (N a ) | (%) |

| Size | ||

| Small hospitals (<100 beds) | 1740 | 49.5 |

| Medium hospitals (100–399 beds) | 1380 | 39.3 |

| Large hospitals (400+ beds) | 392 | 11.2 |

| Teaching Status | ||

| Teaching hospitals | 1379 | 39.3 |

| Nonteaching hospitals | 2133 | 60.7 |

| Location | ||

| Rural hospitals | 1114 | 31.7 |

| Urban hospitals | 2398 | 68.3 |

| System Membership | ||

| Members of a health care system | 2405 | 68.5 |

| Non-system hospitals | 1107 | 31.5 |

| Ownership | ||

| Private, nonprofit | 2077 | 59.1 |

| Private, for-profit | 691 | 19.7 |

| Public, nonfederal | 685 | 19.5 |

| Public, federal | 59 | 1.7 |

N=3512

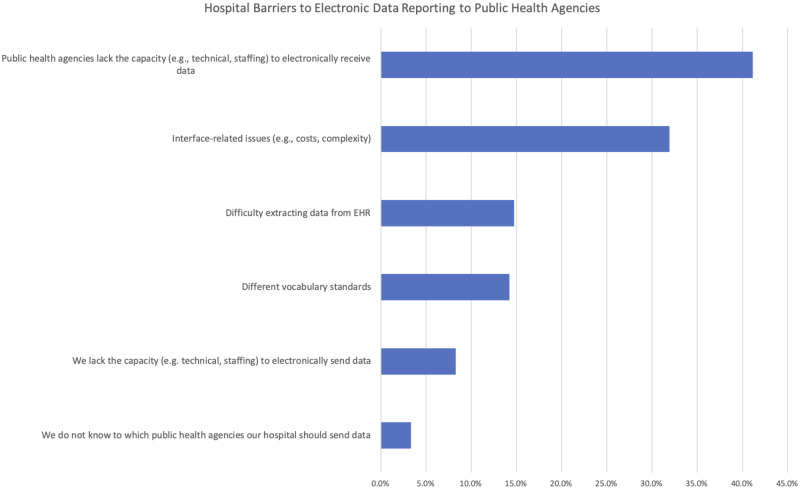

The most prevalent barrier, reported by 41.2% of hospitals, was that public health agencies lacked the capacity to electronically receive data. Interface-related issues (eg, costs, complexity) were the next most common, reported by 31.9% of hospitals. Other barriers included difficulty extracting data from the electronic health record (EHR) (14.7% of hospitals), different vocabulary standards (14.2%), hospitals lack the capacity to electronically send data (8.3%), or hospitals do not know to which public health agencies they should send data (3.3%) (Figure 1). There was significant variation across states in the proportion of hospitals reporting public health agency capacity as a barrier, with Hawaii and Rhode Island (83.3% of hospitals) having the greatest proportion of hospitals reporting it, New Jersey and Virginia at the median (40%), while Delaware (0.0%) had none (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Hospital reported barriers to electronically reporting public health data.

Figure 2.

Variation across states in proportion of hospitals reporting public health agencies unable to electronically receive data.

Note: Map plots the proportion of hospitals in each state reporting that their local public health agency lacks the capacity to electronically receive health information.

We identified 31 HRRs that illustrated both high hospital bed capacity needs and capability gaps with respect to the public health agencies’ ability to accept electronic reporting data, with more than 50% of hospitals reporting public health agencies lacked the capacity to receive data electronically and were also in the top quartile of HRRs in needed bed capacity for COVID-19 patients. The average share of needed beds in these HRRs is 269% of capacity; with 12 557 747 infections projected in these HRRs (12.7% of all projected infections).

DISCUSSION

More than 4 in 10 US hospitals report that public health agencies are unable to receive electronic data. This finding may reflect the fact that substantial federal funding has been devoted to hospital information technology adoption, including the ability to send data electronically, without a concomitant investment in the ability of public health agencies to receive and act upon this data.

We also found variation in hospital-reported barriers to public health reporting across states: 1 state had no hospitals reporting public health agency inability to receive electronic data while several states had the majority of hospitals reporting that barrier. Differential funding-level priorities for public health agencies at the state and local level may explain some of this geographic variation. In-state variation in hospital response—potentially with respect to the same public health agency—may be attributable to state-level public health agencies that are able to only receive selected data elements or only from certain EHR systems—barriers which may manifest differently to different hospitals in the same jurisdiction. All of these sources of variation may leave states without a full surveillance picture from hospitals. Hospitals may also report to both local and state agencies with differing capabilities. The impact of this mismatch is evident in the COVID-19 crisis: many areas reporting barriers to public health receipt of electronic data are also projected to be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, indicating that it is not just low-density or rural areas that lack critical IT infrastructure for electronic disease surveillance.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. We observe barriers at the hospital level and do not have data from public health agencies. Our data is also cross-sectional and represents the state of electronic public health reporting at a given time, and improvements may have been made since 2018. Finally, our data do not ask which specific data elements public health agencies are unable to receive, though they do ask specifically about data used for meaningful use such as syndromic surveillance.

CONCLUSION

COVID-19 has shown that lack of data can hinder pandemic management efforts. Test results and syndromic data should flow seamlessly from hospitals to public health agencies. Policymakers should prioritize investment in public health IT infrastructure along with broader health system information technology for both long-term COVID-19 monitoring as well as future pandemic preparedness.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the concept, design, and drafting of the study. AJH and NCA acquired study data and performed analysis. JAM provided supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

References

- 1. Moore K, Black J, Rowe S, Franklin L.. Syndromic surveillance for influenza in two hospital emergency departments. Relationships between ICD-10 codes and notified cases, before and during a pandemic. BMC Public Health 2011; 11(1): 338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blumenthal D, Tavenner M.. The “Meaningful Use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 501–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lamb E, Satre J, Hurd-Kundeti G, et al. Update on progress in electronic reporting of laboratory results to public health agencies - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64 (12): 328–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sharfstein JM, Becker SJ, Mello MM. Diagnostic Testing for the Novel Coronavirus. JAMA 2020; 323 (15): 1437–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tahir D. Virus hunters rely on faxes, paper records as more states reopen. Secondary Virus hunters rely on faxes, paper records as more states reopen 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/10/coronavirus-health-records-245483 Accessed May 10, 2020.

- 6. Farr C. These ‘disease hunters’ developed a novel technique for tracking pandemics after 9/11, but lost funding right before COVID-19. Secondary These ‘disease hunters’ developed a novel technique for tracking pandemics after 9/11, but lost funding right before COVID-19 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/04/syndromic-surveillance-useful-to-track-pandemics-like-covid-19.html Accessed May 10, 2020.

- 7. Newman S. 2016. National Profile of Local Health Departments. Secondary 2016 National Profile of Local Health Departments 2016. https://www.naccho.org/blog/articles/2016-national-profile-of-local-health-departments.

- 8. Miri A, O’Neill DP.. Accelerating Data Infrastructure for COVID-19 Surveillance and Management Health Affairs Blog; 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200413.644614/full/

- 9. Tsai T, Jacobson B, Jha A.. American Hospital Capacity and Projected Need for COVID-19 Patient Care Health Affairs Blog; 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200317.457910/full/