Abstract

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) mitigation and water treatment are two key aspects towards a sustainable environment, and simultaneous achievement of these two goals is extremely attractive. Inspired by the iron ion catalyzed auto-oxidation of aqueous SO2 (i.e., Fe(II)/sulfite process), that generates intermediary sulfate radical able to oxidize organic compounds, we propose a feasible energy-water-environment nexus by using waste SO2 to alleviate water contamination. As a demonstration, electrolysis is used to assist Fe(II)/sulfite (i.e., electro/Fe(II)/sulfite) process to enhance contaminant removals. Results showed 91% of 10 μM ibuprofen (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) contaminant at neutral pH was removed, due to sulfate radical oxidation. Synergy mechanisms of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process were revealed. Moreover, the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process could effectively degrade contaminants in water bodies from fields, indicating its promising practical application. Energetic analysis indicated that electric treatment cost is 8.65 cent/m3, and is affordable by most water treatment plants. Possible procedures to realize the proposed energy-water-environment nexus were also suggested. The strategy proposed in this study adds new value to the waste produced in energy production and will create renewed interest considering its potential use towards environmental treatment.

Keywords: energy-water-environment nexus, fossil fuel, sulfur dioxide, sulfate radical, water treatment

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

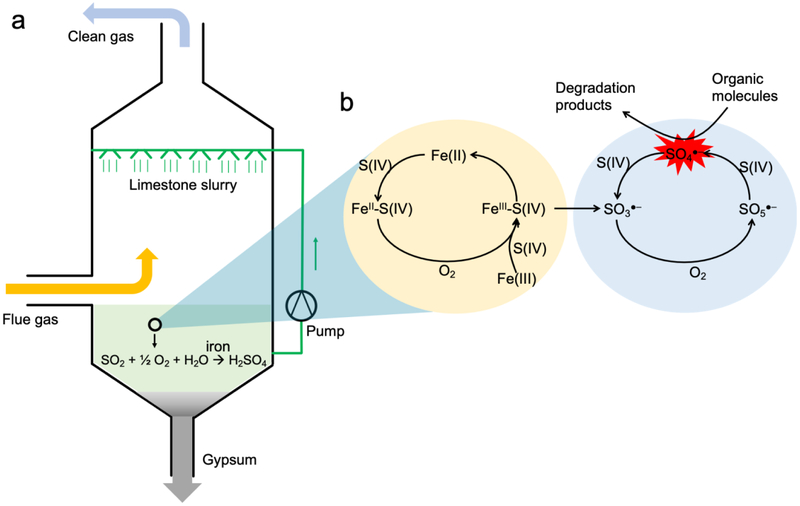

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is regarded as an atmospheric pollutant, which causes acid rain and human respiratory system diseases after short-term exposure [1,2]. Around 100 million tons of SO2 are emitted into the atmosphere annually [3], a large fraction of which is produced by the fossil fuel power plants although clean oil and gas production techniques are being developed [4,5]. It is hence imperative that power plants flue gas must be desulfurized before emission into the atmosphere. The most widely adopted technique to remove SO2 from the emitted flue gas of power plants is called flue gas desulfurization (FGD) process. Conventional FGD process relies on a sprayed limestone slurry to scrub dissolved SO2 in water droplets (Fig. 1a) [6,7]. During the FGD process, trace metals present in solution such as iron ions are catalytically active to convert SO2 into sulfuric acid through “bi-cycle” radical chain reactions (Fig. 1b) [8,9]. Briefly, the first cycle of iron species turnover generates SO3•− (sulfite radical) (Equations 1-4), which then initiates the second cycle of oxysulfur radical evolution to sequentially derive SO5•− (peroxymonosulfate radical) and SO4•− (sulfate radical) in the presence of O2 (Equations 5-7). These oxysulfur radicals, particularly SO4•−, are as highly reactive as hydroxyl radical (HO•), and they can potently degrade the co-existed organic molecules [9]. Inspired by this, we coupled ferrous iron catalyst and aqueous SO2 (i.e., Fe(II)/sulfite process) to treat various organic contaminants, such as azo dyes [10], endocrine disruptor [11], herbicide [12], and pharmaceutical [13]. Owing to the strong bactericidal potential, SO4•− was also used to inactivate water pathogens [14].

Fig. 1.

(a) Conventional FGD process to desulfurize the flue gas of fossil fuel power plants, and (b) “bi-cycle” radical chain reactions of iron catalyzed sulfite auto-oxidation that could degrade organic molecules during FGD process. S(IV) denotes sulfite, including HSO3−/SO32−.

Cycle of Fe(II/III) turnover:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Cycle of oxysulfur radicals evolution:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Two major challenges impede the application of Fe(II)/sulfite process into practical water treatment. First, the Fe(II)/sulfite process generates SO4•− effectively at pH below 5, but the capability rapidly diminishes at near-neutral pH due to iron precipitation [10]. Since most water bodies in the fields are neutral [15,16], the effectiveness of the Fe(II)/sulfite process is compromised. Recently, researchers have used chromium [17], copper [12], manganese [14], and metallic composites [13] as catalysts to replace iron ions for sulfite activation. However, these new types of catalysts suffer from significant toxicity to human beings, low catalytic activity, and high preparation cost, respectively [9]. Therefore, Fe(II)/sulfite process is still a dominant sulfite activation platform. Secondly, it can be seen from Equations 1-7 that the SO4•− generation by the Fe(II)/sulfite process is strongly dependent on solution O2 content. However, the evolution of oxylsulfur radicals in the second cycle of Fe(II)/sulfite process causes rapid depletion of dissolved oxygen within tens of seconds, far exceeding the dissolution rate of atmospheric oxygen [9,10]. The rapid depletion of solution O2 was widely observed in batch reaction of various volumes [14]. The low oxygen content retards the turnover of Fe(II/III) in the first cycle and oxysulfur radical evolution in the second cycle, leading to relatively weak SO4•− generation.

To address the above challenges, we here apply electricity to Fe(II)/sulfite process (i.e., electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process). This is because 1) electrolysis is able to create local acid zone around the anode [18], 2) electrolytically generated nascent oxygen [19] can support the “bi-cycle” reactions, and 3) electrolysis of sulfite solution directly produces the oxysulfur radicals (i.e., SO3•−, SO5•− and SO4•−) [20] for possible organic contaminants degradation. To date, this novel energy-water-environment nexus utilizing fossil fuel combustion waste SO2 for enhanced water treatment has never been reported previously. As a bench-scale demonstration, sulfite represents the captured SO2 from flue gas and ibuprofen (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) is selected as a typical water contaminant [21]. The electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process was used to degrade ibuprofen at neutral pH that is close to natural conditions.

In this strategy, the waste SO2 from electrical energy generation is instead a useful resource holding unexplored chemical energy that can be used to treat contaminated water. Therefore, the aim of this work is to thoroughly investigate the feasibility of applying chemical energy of SO2 into water treatment. Techno-economic analysis indicates that the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process is energetically viable and relatively low-cost. The possible procedures to realize this process are also proposed to facilitate future research. It is anticipated that, this feasible energy-water-environment nexus could simultaneously achieve SO2 mitigation and sustainable water treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Sodium sulfite (Na2SO3), ferrous sulfate (FeSO4), and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) were purchased from Acros Organics (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Ibuprofen (2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propanoic acid, C13H18O2) used as the target compound was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). Ethanol (reactive toward SO4•−) and tert-butanol (inert toward SO4•−) from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. were used to identify SO4•−, because of their selective oxidation property. Details were also included in Section 3.4. Milli-Q water was used throughout this study unless indicated. All other chemicals were from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

2.2. Ibuprofen degradation experiments

The reactor to carry out experiments is shown in Fig. S1 of supplementary material. Ibuprofen degradation assays were performed under different conditions. Typically, 400 mL solution of 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, and 10 mM Na2SO4 as supporting electrolyte was prepared in a beaker, and immediately adjusted to pH 7 with 0.1 M NaOH or H2SO4. Solution of pH was recorded with a pH meter (Mettler Torledo). During the reaction, the uncontrolled change of solution pH was constantly monitored. 0.1 mM Fe(II) was diluted from a 100 mM FeSO4 stock solution that was prepared in advance and stored in 4 °C refrigerator. Two identical Ti-based mixed metal oxide (Ti/MMO) mesh electrodes (5 cm2) with a fixed distance of 5 cm were placed in parallel in the reactor as anode and cathode, and a 200-mA constant current was applied by an Agilent E3612A DC power supply. The solution was constantly stirred by a PTFE-coated magnetic bar. Parameters including sulfite concentration, current intensity, and solution pH are varied if stated to study their effects on ibuprofen removal. Specifically, the effect of sulfite concentration (0-2.5 mM), current intensity (0-200 mA), and solution pH (4-10) were investigated toward ibuprofen degradation efficiency. For carbonate buffering effect, solutions containing 0.5, 1, or 2 mM Na2CO3 and indicated amounts of Fe(II) and/or sulfite were used. Solutions were rapidly adjusted to pH 7 prior to initiation of assays.

2.3. Analysis methods

At specific times, 1 mL samples were collected from the solution and the reactions were stopped by adding 1 mL of 100 mM ethanol. Before quantification, all samples were filtered through 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes. Concentrations of ibuprofen were then analyzed by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1200 Infinity Series) equipped with an Agilent Eclipse AAA C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm). 0.5 mL/min methanol/1% phosphoric acid (68/32) was used as the mobile phase, and ibuprofen was detected at 228 nm wavelength using Agilent 1260 diode array detector. Sulfite concentrations were quantified using a modified high throughput method [22], with an injection volume of 100 μL. The detection limit of this modified method is 0.05 mM. Solution pHs were recorded during a brief switch off of current supply to exclude the disturbance of electrodes electrolysis. All assays were conducted for triplicates. The ibuprofen pseudo first-order degradation rate constant (k) was obtained by calculating the slope of ln(Ct/C0) versus time curve.

2.4. Quantifications of dissolved Fe(III) via colorimetric assays

Concentration of dissolved Fe(III) (i.e., [Fe(III)]dissolved) was calculated from total dissolved iron concentration (i.e., [total iron]dissolved) minus the dissolved Fe(II) concentration (i.e., [Fe(II)]dissolved) (Equation 8). Total dissolved iron concentration was measured via a colorimetric assay. In details, 1 mL sample after filtration with 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes was added into solutions containing 4 mL of 1,10-o-phenanthroline (17 mM) and 2 mL of potassium hydrogen phthalate (20 mM). 0.5 mL of 10 mM hydroxylamine was used to reduce Fe(III) into Fe(II). After reaction for 15 min, all Fe(II) complexed with 1,10-o-phenanthroline into a pink product with peak wavelength of 510 nm, and was then quantified with a UV-Vis spectrometer. Dissolved Fe(II) concentration was quantified through the same manner, without addition of hydroxylamine.

| (8) |

2.5. Cyclic voltammetry

The cyclic voltammetry of sulfite solution has been performed with many electrodes [20,23,24], and we attempt to further investigate the sulfur species evolution on Ti/MMO electrode in this study. Both 0-10 mM sulfite and 100 mM sodium sulfate electrolyte were prepared in 200 mL solution. To run cyclic voltammetry for the sulfite solution, a Ti/MMO electrode (2 cm2) was used as the working electrode, a Pt electrode (4 cm2) as the counter electrode, and a saturated Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode. Scans were performed from −0.6 V to 1.7 V (vs SHE, standard hydrogen electrode) at a rate of 50 mV/s with SP-300 electrochemical workstation (BioLogic, France). Stable and closed cyclic voltammetry curves, which represent the steady-state electrocatalytic reactions, were obtained typically after two runs. 0.1 mM EDTA solution was used when stated, to exclude the effect of metal catalysis for sulfite oxidation on Ti/MMO anode. All cyclic voltammetry assays were performed at pH 7.

2.6. Electron spin resonance assay

To further probe the produced intermediate of the electro/sulfite reaction, 50 mM 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolidine-N-oxide (DMPO) solution was used to trap the generated radical. Both the electro/sulfite reaction (1 mM sulfite solution and 200 mA current at pH 7) and the control reactions (1 mM sulfite solution or 200 mA current at pH 7) were carried out at room temperature for 1 min. Samples withdrawn by a capillary tube were inserted into the cavity of the electron spin resonance spectrometer (JES-FA200, Japan Electron Optics Laboratory Co. Ltd., Japan) for analysis under the following parameters: center field, 326 mT; sweep width, 30 mT; microwave frequency, 9.147 GHz; microwave power, 3 mW.

2.7. Radical-scavenging assay

Tert-butanol (inert toward SO4•−) and ethanol (reactive toward SO4•−) were used to scavenge relevant radicals in the Fe(II)/sulfite (0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, initial pH 7), electro/sulfite (1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA current, initial pH 7), and electro/Fe(II)/sulfite (0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA current, initial pH 7) processes. 5 mM or 10 mM of tert-butanol and ethanol solutions were individually added into each of the three solutions containing 10 μM ibuprofen, and ibuprofen concentrations were immediately analyzed by HPLC after specific sampling times.

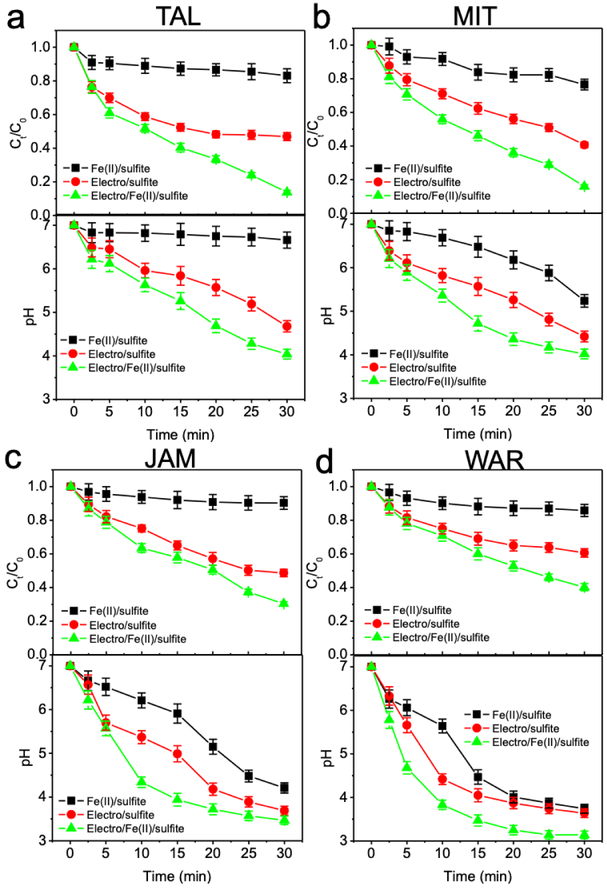

2.8. Removal of ibuprofen from field water matrices

Ibuprofen degradations by Fe(II)/sulfite, electro/sulfite, and electro/Fe(II)/sulfite processes were tested in four water bodies from fields, i.e., two groundwaters extracted from our Tallonal (TAL) and Pozo Mita (MIT) Superfund sites in Puerto Rico, and two surface waters collected from local Jamaica pond (JAM) and Wards pond (WAR) in Boston, Massachusetts. Extracted water matrices were filtered through 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes for three times to remove suspended solid particles, and subsequently stored in a 4 °C cold room. During ibuprofen degradation assays, 10 μM ibuprofen were prepared in 400 mL field water matrices, and then treated by Fe(II)/sulfite (0.2 mM Fe(II), 2 mM sulfite, initial pH 7), electro/sulfite (2 mM sulfite, 200 mA, initial pH 7), and electro/Fe(II)/sulfite (0.2 mM Fe(II), 2 mM sulfite, 200 mA, initial pH 7) processes. The intrinsic conductive ions together with added iron and sulfite supported the electrolysis reactions, without additional use of sulfate electrolyte.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process for water treatment

It is reported that during FGD process, trace iron ions catalyze the auto-oxidation of aqueous SO2 (sulfite), and three intermediary oxysulfur radicals (i.e., SO3•−, SO5•−, and SO4•−) are generated [8,9]. Among them, SO4•− is the most powerful radical and could oxidatively degrade a large variety of organic compounds. Fe(II)/sulfite process was then developed for organic contaminants degradation inspired by this [10]. The most intriguing feature of the Fe(II)/sulfite process for water treatment is that both Fe(II) and Fe(III) are catalytically active toward sulfite oxidation (supplementary material Fig. S2) [9]. Therefore, the persistent turnovers of minimum iron dose can continuously steer sulfite activation to produce immense SO4•− radicals for organic contaminant degradation.

As shown in Fig. 2a, Fe(II)/sulfite process produced moderate oxidation capability at neutral pH. A solution of 0.1 mM Fe(II) and 1 mM sulfite mediated 28% removal of 10 μM ibuprofen after 30 min at pH 7. By comparison, solutions with only Fe(II) or only sulfite did not induce any noticeable removal of ibuprofen. It is expected that, the SO4•− generated from the Fe(II)/sulfite reaction was primarily responsible for ibuprofen removal [10]. But the Fe(II)/sulfite process was majorly hindered by significant precipitative deactivation of Fe(II) at near-neutral pH, which explained the incomplete ibuprofen removal observed in Fig. 2a.

Fig. 2.

(a) Electrolysis enhanced Fe(II)/sulfite process toward ibuprofen removal at neutral pH, and (b) ibuprofen pseudo first-order degradation rate constant (k) linearly increased versus current intensity. Conditions: 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, initial pH 7.

Application of 200 mA electric current to the Fe(II)/sulfite (i.e., electro/Fe(II)/sulfite) process greatly enhanced ibuprofen removal (Fig. 2a). Up to 91% of 10 μM ibuprofen was removed by the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process after 30 min, reflecting a 3.6-fold enhancement of the ibuprofen pseudo first-order degradation rate constant (k) compared with Fe(II)/sulfite process. Moreover, the enhancement of ibuprofen degradation kinetics appeared to be linearly correlated with current intensity in the range of 0-200 mA (Fig. 2b). The mechanism of enhanced ibuprofen degradation is investigated and discussed below.

3.2. Synergy mechanism of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process

3.2.1. Mechanism 1: acid zone around anode supported Fe(II)/sulfite process

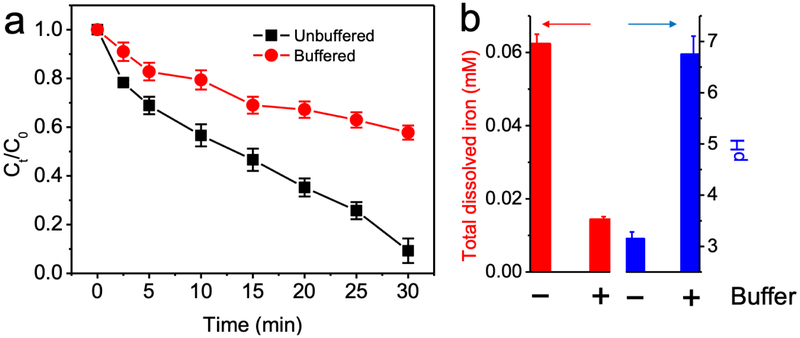

During Fe(II)/sulfite process treatment, iron ion catalyst shows higher catalytic activity at acidic pH. Electrolysis of water solution is able to create an acid zone around the anode, due to the intense generation of protons [18]. As a result, the solution pH around the anode was 3.3 while the bulk solution pH was neutral in our experiment. The local acidification due to anode electrolysis significantly improved iron catalytic activity, and consequently enhanced water treatment efficiency of Fe(II)/sulfite process. To further validate the role of acid zone around the anode, ibuprofen degradation was performed by electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process with 50 mM Tris buffer. Significantly less ibuprofen removal was observed (Fig. 3a), because of weakened acidification effect and minimum dissolved iron catalyst (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

(a) Degradation of ibuprofen by electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process in unbuffered or buffered solution, and (b) total dissolved iron concentration and pH at the end of reaction. Conditions: 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, with or without 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7. Reaction for 30 min.

3.2.2. Mechanism 2: electrolytic oxygenation supported Fe(II)/sulfite process

As shown in Equations 1-7, Fe(II)/sulfite process efficiency is highly dependent on oxygen content, which supports both the turnovers of iron species in the first cycle and evolution of oxysulfur radicals in the second cycle. With sufficient oxygen, repeated turnovers of a minimum dose of iron, regardless of Fe(II) or Fe(III), will continuously drive sulfite auto-oxidation and produce SO4•−. However, the low oxygen content (Fig. 4a), mainly because SO3•− scavenged O2 at an approaching-diffusion rate (Equation 5) [25], could adversely reduce SO4•− radical yield by inhibiting the conversion of Fe(II) into Fe(III) (first cycle) and also retarding SO3•− evolution to SO4•− (second cycle).

Fig. 4.

Changes of (a,b) dissolved oxygen, (c,d) dissolved Fe(III), (e,f) sulfite concentration, and (g,h) ibuprofen concentration in Fe(II)/sulfite, oxygenated Fe(II)/sulfite, and electro/Fe(II)/sulfite processes at pH 4 or pH 7. Conditions: Fe(II)/sulfite – 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4; oxygenated Fe(II)/sulfite – 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 1 L/min oxygenation; electro/Fe(II)/sulfite – 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA.

We first showed that purging gaseous O2 to enhance the oxygen content (Fig. 4a,b) could remarkably accelerate the turnovers of dissolved Fe(II/III) catalyst (represented by conversion of Fe(II) into Fe(III)) (Fig. 4c,d) and oxysulfur radicals evolution (represented by sulfite consumption) (Fig. 4e,f), and thus consequently enhance ibuprofen degradation by Fe(II)/sulfite process particularly at acidic pH (Fig. 4g,h). For instance, k was increased from 0.0961 to 0.2591 min−1 at pH 4, and from 0.0151 to 0.0308 at pH 7, after oxygenation to the Fe(II)/sulfite process (Fig. 4g,h). The diminished catalytic activity of iron at alkaline pH, due to precipitation, caused the low oxidation capability of the Fe(II)/sulfite process, and additional oxygenation did not enhance ibuprofen removal (Fig. 4h).

Electrolysis was then manifested as a mechanism to generate nascent O2, instead of purging gaseous oxygen, to accelerate the “bi-cycle” of Fe(II)/sulfite process (Fig. 4). This is because, the O2 generated from water electrolysis tends to be hydrated and more actively engaged in aqueous reactions compared with purged gaseous oxygen [19]. As a result, electrolysis of 400 mL solution with 200 mA current, corresponding to 0.7 mL O2/min generation under utmost faradaic efficiency, recovered the dissolved oxygen contents of Fe(II)/sulfite reaction solution similarly to those produced by purging 1 L/min gaseous O2 (Fig. 4a,b). Moreover, the oxidation capability of Fe(II)/sulfite reaction was observed to be positively correlated with the oxygenation rate (supplementary material Fig. S3). As a result, increasing the current intensity led to more nascent O2 generation, and consequently mediated stronger oxidation capability of the Fe(II)/sulfite process (Fig. 2b). We hence conclude that electrolytic oxygenation played a vital role to enhance the oxidation capability of the Fe(II)/sulfite process.

3.2.3. Mechanism 3: electro/sulfite reaction generated sulfate radical

It was also observed that, electrolysis of the sulfite solution under 200 mA current without Fe(II) catalyst (i.e., electro/sulfite process) mediated a significant fraction of ibuprofen removal (34% removal within 30 min), compared to almost no removal of ibuprofen by either electrolysis or sulfite treatment alone (Fig. 2a). Reactive intermediates generated in the electro/sulfite reaction were likely responsible for ibuprofen removal. Below we investigate the mechanism of radical generation by electro/sulfite reaction.

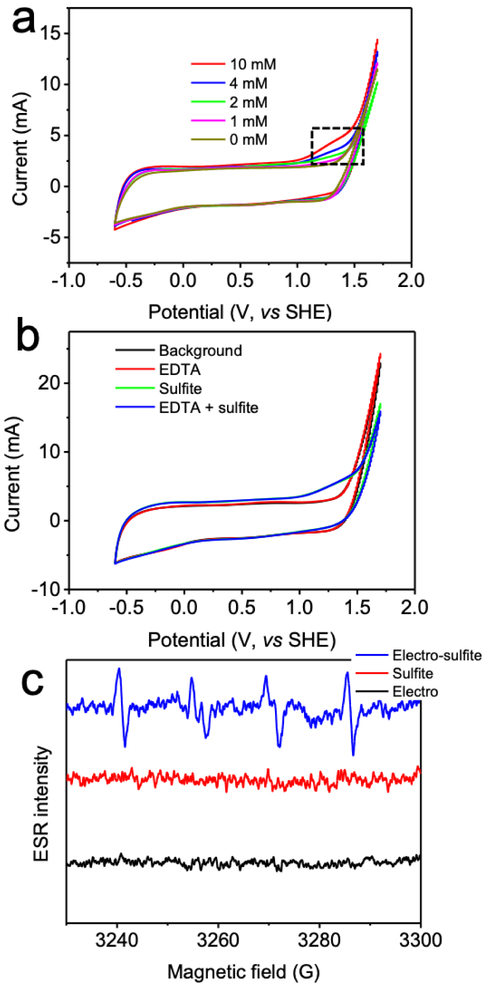

Previous reports indicated that sulfite could be oxidized on both active (e.g. graphite, glassy carbon) [20,26] and inert anodes (e.g. noble metal, metal oxide) [24,27], in which direct electron transfer is the predominant mechanism. Cyclic voltammetry was at first performed to detect electron transfer from sulfite to Ti/MMO anode (Fig. 5a). A peak of onset potential at 1.1 V (vs SHE) in the anodic scan of the sulfite solution climbed above the background current, corresponding to sulfite oxidation. The peak height of the signal increased while increasing the concentration of sulfite, which was consistent with the literature [23].

Fig. 5.

Electro/sulfite reaction mechanism investigated through (a,b) cyclic voltammetry, and (c) electron spin resonance assay. Conditions: (a) 0-10 mM sulfite, 100 mM Na2SO4, pH 7, 50 mV/s scan rate; (b) 10 mM sulfite, 0.1 mM EDTA, 100 mM Na2SO4, pH 7, 50 mV/s scan rate; (c) 50 mM DMPO, 1 mM sulfite, 200 mA current, 10 mM Na2SO4, pH 7. DMPO/SC3•− adduct (aH• = 16.0 G, aN = 14.7 G) showed up in electro-sulfite reaction. Note: DMPO, 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolidine-N-oxide.

It was further revealed that, unlike transition metal mediated sulfite auto-oxidation which requires intermediary metal-sulfite complex [9], anodic sulfite oxidation is free from participation of metal species in Ti/MMO electrode since EDTA complexation did not inhibit the electron transfer from sulfite to anode (Fig. 5b). Anodic sulfite oxidation is a pure single-electron transfer process from the adsorbed sulfite molecules to the immediate conductive surface of the Ti/MMO electrode, consistent with the mechanism of sulfite oxidation on other electrodes [20].

Sulfite oxidation on the anode is accomplished via two successive single-electron transfers involving the formation of SO3•− radical [20]. Herein, we attempted to further validate the radical-electron mechanism by directly capturing the intermediary SO3•− of the electro/sulfite reaction using electron spin resonance (Fig. 5c). A pronounced signal corresponding to DMPO/SO3•− adduct (aH• = 16.0 G, aN = 14.7 G) [28,29] was observed in electro/sulfite reaction, whereas electrolysis or sulfite alone did not produce any such signal. The presence of SO3•− radical, as a result of sulfite oxidation by anode under high redox potential, corroborated the mechanism of a single-electron transfer from sulfite to anode. Following the discharge of adsorbed sulfite on the anode surface, the generated SO3•− could evolve into SO4•− via Equations 9-11 (ads denotes adsorbed). Ibuprofen degradation by SO4•− generated from sulfite oxidation on Pt anode was also observed (supplementary material Fig. S4), following the same mechanism. Since these transient oxysulfur radicals are relatively short-lived, the electro/sulfite reaction is hence an in situ sulfite discharge process followed by radical chain reactions (Equations 9-11) on anode surface (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Illustration of the synergy mechanism of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process for organic contaminant degradation. S(IV) denotes sulfite, including HSO3−/SO32−.

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

3.3. Effect of pH and sulfite dose

3.3.1. Effect of pH

Fe(II)/sulfite process efficiently removed ibuprofen at acidic pH, and its capability rapidly declined at higher pH (Fig. 7a). At pH 4, k was 0.0961 min−1, and it decreased to 0.0151 min−1 at pH 7. At pH higher than 7, negligible ibuprofen removal was observed. This is because iron ion starts to precipitate at pH 5 and catalytic activity quickly decays as a consequence.

Fig. 7.

Effect of (a-c) pH and (d-f) sulfite concentration over ibuprofen pseudo first-order degradation rate constant (k) by the Fe(II)/sulfite, electro-sulfite, and electro-Fe(II)/sulfite processes. Conditions: Fe(II)/sulfite process – 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, initial pH 7; electro/sulfite process – 10 μM ibuprofen, 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, initial pH 7; electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process – 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, initial pH 7. Solution pH and sulfite concentration varied as indicated.

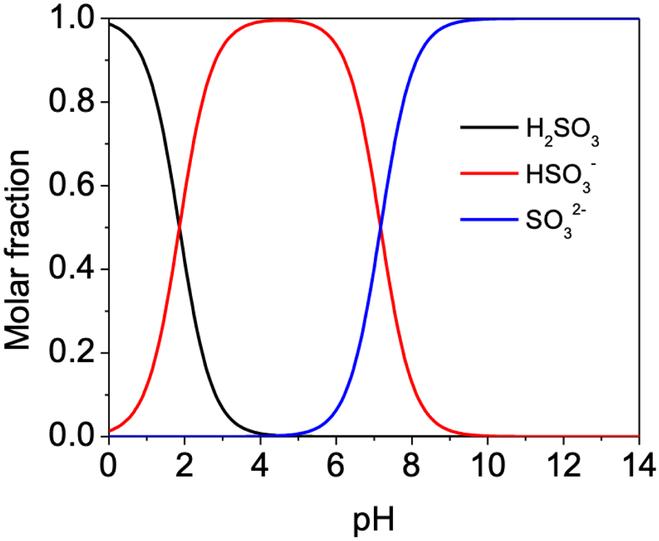

The effect of pH over the ibuprofen degradation by electro/sulfite process was also investigated. The degradation efficiency of ibuprofen by electro/sulfite process was more evident at alkaline pH (Fig. 7b). For instance, k was improved from 0.0144 min−1 at pH 7 to 0.0837 min−1 at pH 10 in the electro/sulfite process. Sulfite (pKa = 7) species variation [30] subjected to solution pH presumably accounted for this, since SO32− formed at alkaline pH (SO32− → SO3•− + e−, E0 = 0.63 V vs SHE) [30] was easier to be oxidized than its counterpart in acidic pH (HSO3− → H+ + SO3•− + e−, E0 = 0.84 V vs SHE) [25]. Notably, the profile of k value against pH slightly differed from that of sulfite species variation against pH. For instance, the fraction of SO32− was plateaued above pH 9 (Fig. 8), but k continued to exponentially increase until pH 10 (Fig. 7b), consistent with the steady-state concentration of SO4•− calculated from benzoic acid quantification assays (supplementary material Fig. S5). An acidic electrolyte layer in the vicinity of anode due to proton release, which lowered the pH around anode than in bulk solution [23], likely accounted for this shift in pH effect.

Fig. 8.

Sulfite species distribution against pH in the range of 0-14.

Collectively, the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process for water treatment was composed of the electrolytically oxygenated Fe(II)/sulfite process and the electro/sulfite process. As a result, the simultaneous roles of electrolytic oxygenation (that remarkably enhanced Fe(II)/sulfite oxidation capability at acidic pH) (Fig. 7a) and anodic sulfite oxidation (that significantly mediated ibuprofen degradation at alkaline pH) (Fig. 7b) together led to an upward parabola pattern in pH effect over ibuprofen degradation by the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process (Fig. 7c).

3.3.2. Effect of sulfite dose

The role of sulfite concentration was also explored, as sulfite is the precursor of derived SO4•− radical. In the Fe(II)/sulfite process, increase of sulfite concentration initially improved the oxidation capability; however, higher concentration (over-dose) of sulfite reduced SO4•− generation due to self-scavenging (Fig. 7d) [31]. A typical molar ratio of 1:10 (Fe(II):sulfite) usually led to optimal substrate oxidations [10].

In contrast, ibuprofen oxidation rate by the electro/sulfite process linearly increased against sulfite concentration, and self-scavenging was not observed within the tested range (i.e., 0-2 mM sulfite) (Fig. 7e). Unlike homogeneous Fe(II)/sulfite reaction, only adsorbed sulfite molecules participated in the electron transfer during electro/sulfite process [23] followed by oxysulfur radical evolution to derive SO4•−. Consequently, higher sulfite concentration in bulk solution linearly increased sulfite occupancy of active sites on the anode surface, and mediated higher SO4•− generation efficiency via above steps.

During water treatment by electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process in neutral solution, the locally induced acidic zone and electrolytic oxygenation near the anode that both favorably promoted the Fe(II)/sulfite process, played a dominant role in the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process, and consequently mediated a volcano pattern of k versus sulfite dose (Fig. 7f).

3.4. Dominant role of sulfate radical

The group of oxysulfur radicals (i.e., SO3•−, SO5•−, and SO4•−) have been found to react with organic substrates under different conditions. In details, SO3•− accounts for substrate removal in anaerobic assays, in which SO5•− and SO4•− do not exist [32]. Under aerobic conditions, SO3•− is completely transformed into SO5•− and SO4•− (Equations 5-7), which then tend to oxidize distinct species of substrates. SO5•− shows high reactivity towards anilines [33], whereas SO4•− has much broader selectivity including phenols, alcohols, and azo dyes [9]. Therefore, SO4•− most likely accounted for ibuprofen removal with the three aerobic processes (i.e., Fe(II)/sulfite, electro/sulfite, and electro/Fe(II)/sulfite) in this study.

A well-established differential method was adopted to identify SO4•−. In short, ethanol scavenges SO4•− at a relatively high reaction rate [31], while tert-butanol is quite inert toward SO4•− [34]. Utilizing this method, tert-butanol at up to 10 mM (1000-fold of ibuprofen concentration) did not affect the oxidation of ibuprofen, while the addition of ethanol significantly inhibited ibuprofen removal in the three processes (Fig. 9). In particular, with 10 mM ethanol, almost complete inhibition of ibuprofen oxidations was observed in three processes. As expected, SO4•− was the predominant radical responsible for the oxidation of ibuprofen in all three processes.

Fig. 9.

Identification of sulfate radical in (a) Fe(II)/sulfite process, (b) electro/sulfite process, and (c) electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process through radical-scavenging assays. Conditions: (a) 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, initial pH 7; (b) 10 μM ibuprofen, 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, initial pH 7; (c) 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.1 mM Fe(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, initial pH 7.

Furthermore, the attacking mode of SO4•− has been investigated previously [35]. In details, SO4•− abstracts an electron from the organic compound, and forms stable sulfate anion (i.e., SO42−). The oxidation products of the organic substrate are at first an addition product between the aromatic ring and sulfate group, followed by its hydrolysis into hydroxylated aromatic ring. The intermediate organic radicals will continuously propagate until stable products are formed. To investigate the degradation mechanism, degradation products of ibuprofen by the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process were scanned (Q1 MS mode) in the range of 50 to 300 Da using HPLC-MS (supplementary material Text S2), and several fingerprint products of ibuprofen transformation by SO4•− were identified (supplementary material Fig. S6 and S7). Specifically, SO4•− at first oxidized either the butyl group leading to byproduct 2 (4-(1-carboxyethyl)benzoic acid), or carboxyl group leading to byproduct 3 (4-isobutylacetophenone). Both byproducts 2 and 3 could be oxidized by SO4•− into byproduct 4 (4-acetylbenzoic acid), followed by further oxidative transformations. The proposed ibuprofen degradation pathway was consistent with previous reports [36-38], validating the contribution of SO4•− during the transformation.

3.5. Treatment of other water contaminants

Besides ibuprofen, several other water contaminants were tested (supplementary material Fig. S8). Particularly, 4-chloroaniline and N,N-dimethylaniline are precursors for industrial dyes or insecticides [39]; paracetamol is a drug for fever or headache [40]; and Orange II, Rhodamine B, and Reactive Brilliant Red are common dyes of textile industry [41]. They are considered recalcitrant contaminants since microbial activities are ineffective towards their degradations. Their quantification methods were included in Table S1 of supplementary material. It was shown that electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process could remove 70-97% of these compounds at a concentration of 10 μM at pH 4, significantly higher than Fe(II)/sulfite or electro/sulfite process (supplementary material Fig. S8). The removal efficiencies were slightly lower at pH 7, ranging from 52-82% by electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process (supplementary material Fig. S8). The structure and molecular weight are shown in Table S2 of supplementary material. The slightly lower removal efficiencies of 4-chloroaniline and Reactive Brilliant Red are possibly ascribed to the low electron density of aromatic rings due to the presence of heteroatoms such as nitrogen and chloride. Nevertheless, it is believed that, electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process could non-selectively degrade a wide variety of water contaminants, showing potential applications into practical water treatment.

3.6. Treatment of field water bodies

Our final goal is to apply electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process to treat natural contaminated waters. However, water bodies in the fields often contain strong buffering agent that might compromise the water treatment efficiency of most technologies. Carbonate is the most common buffering agent in field water bodies, in the range of 0.2 – 2 mM [42,43]. It was observed that electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process could efficiently resist carbonate buffering effect (supplementary material Fig. S9), and removed up to 76% ibuprofen in solution containing 2 mM carbonate (supplementary material Fig. S9l). Moreover, treatment of water matrices of various carbonate contents by electro/sulfite process, led to over 80% removal of 10 μM ibuprofen after three consecutive additions of sulfite (supplementary material Fig. S10 and S11), highlighting a promising use of electro/sulfite process to treat water if iron is prohibited.

Ibuprofen removals from water samples collected from the fields were then tested by the Fe(II)/sulfite, electro/sulfite, and electro/Fe(II)/sulfite processes, respectively. Specifically, two groundwater samples with high carbonate alkalinity were extracted from Superfund sites of karst topography in Puerto Rico, and two typical surface waters containing high organic carbon contents were sampled from local Boston ponds (Table 1). Considering the complex conditions of natural groundwater matrices, we doubled the concentrations of Fe(II) and sulfite. Intrinsic ions in the field water bodies, together with the added Fe(II) and sulfite, supported the conductivity of the electrolysis. As a result, over 80% of ibuprofen was removed by the electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process in samples collected from two groundwater wells (referred to as TAL and MIT), compared to lower ibuprofen removal by both Fe(II)/sulfite and electro/sulfite processes (Fig. 10a,b). On the other hand, removals of ibuprofen in the surface water samples (referred to as JAM and WAR) by electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process were slightly lower (Fig. 10c,d), presumably due to the high content of organic carbon present in these samples (Table 1). Organic carbon owns similar reactivity with ibuprofen towards SO4•−, and such competition would spare a large fraction of SO4•− for organic content oxidation. Besides, the high carbonate alkalinity (Table 1) might also compromise ibuprofen oxidation by affecting solution pH.

Table 1.

Characterizations of used field water matrices for ibuprofen removal assays.

| TAL | MIT | JAM | WAR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.70 | 7.51 | 7.34 | 7.81 |

| DO (mg/L) | 7.94 | 7.86 | 8.14 | 7.94 |

| ORP (mV, vs Ag/AgCl) | 315 | 281 | 347 | 329 |

| TOC (mg/L) | 79.8 | 73.37 | 307 | 448 |

| Alkalinity (mg/L) a | 150 | 123 | 48 | 81 |

Note: TAL, Tallonal Superfund site; MIT, Pozo Mita Superfund site; JAM, Jamaica pond; WAR, Wards pond. DO, dissolved oxygen; ORP, oxidation/reduction potential; TOC, total organic carbon.

water alkalinity was presented in the form of CaCO3 (ref. 66).

Fig. 10.

Degradation of ibuprofen in field groundwater matrices extracted from (a) TAL and (b) MIT Superfund sites of Puerto Rico, and in natural surface water matrices collected from local (c) JAM and (d) WAR ponds of Boston, Massachusetts. Conditions: Fe(II)/sulfite process – 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.2 mM Fe(II), 2 mM sulfite, initial pH 7; electro/sulfite process – 10 μM ibuprofen, 2 mM sulfite, 200 mA, initial pH 7; electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process – 10 μM ibuprofen, 0.2 mM Fe(II), 2 mM sulfite, 200 mA, initial pH 7. Note: TAL, Tallonal Superfund site; MIT, Pozo Mita Superfund site; JAM, Jamaica pond; WAR, Wards pond.

3.7. Feasibility and energetic analysis

Feasibility and energetic analysis of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process are performed to gain more insights. Various sophisticated water treatment techniques have been developed to meet different demands. For example, wet oxidation under high air pressure is an energy-intensive process and is used to treat concentrated biomass and organic matters [44,45]. Membrane filtration (such as reverse osmosis and ultrafiltration) is installed at the terminal of a centralized water treatment facility to obtain ultrapure water, and this unit faces the problem of costly membranes [46]. More platforms are discussed in Table S3 of supplementary material. Advanced oxidation process (AOP) using various oxidative radicals such as SO4•− is a quite common water pretreatment process [47]. AOP is usually utilized to remove recalcitrant contaminants so as to alleviate the burden of following units. The herein developed electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process belongs to AOP family, which is used to preliminarily eliminate most hazards. In practice, this process can be performed by simply adding iron ions and collected sulfite under electric current.

The energetic analysis is then conducted to evaluate the energy cost of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process. Over the course of reactions, applied electric current was 200 mA, and cell voltage was around 5 V, and experiments endured for 30 min. Therefore, the energy used to treat 400 mL solution was determined to be 0.5 W·h by Equation 12. Given that the average industrial electricity price is 6.92 cent/(KW·h) in US [48], the electric treatment cost is 8.65 cent/m3 as estimated by Equation 13, where P is the price of electricity and E is the energy cost to treat 1 m3 water.

| (12) |

| (13) |

The cost of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process is significantly lower than many other water treatment processes. For example, Fenton reaction (Fe(II)/H2O2) generating hydroxyl radical (HO•) is a classical AOP in water treatment industry [49,50]. However, several aspects increase the treatment cost of Fenton reaction. At first, Fe(II) is much more catalytically active than Fe(lll) to transform H2O2 into HO• [49]. This requires continuous addition of Fe(II) ions during practical water treatment. Besides the increased reagent cost, the treatment of iron hydroxide sludge is another concern [51]. Secondly, the price of liquid H2O2 is $750/ton (50%) [52], and the overall cost could be higher by considering its storage and transportation. It is reported that the cost for Fenton process treatment is around $0.6/m3 (after translation of euro into US dollar) [53], and the cost could rise up to $10-30/m3 when the targets are high-strength wastewater [54,55]. In sharp contrast, utilization of sulfite for water treatment is a net gain in terms of cost, because sulfite is otherwise a waste. Besides Fenton process, the cost of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process is also significantly lower than many other well-established water purification facilities. For instance, a standard ultrafiltration system costs around $0.28/m3 in a large plant [56], and costs of ion exchange and reduction/coagulation for heavy metal removal are $0.29/m3 and $0.38/m3, respectively [57]. The electricity energy cost of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process (8.65 cent/m3) is significantly lower than these processes. Collectively, our proposed electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process for water treatment is not only sustainable but also rather low-cost.

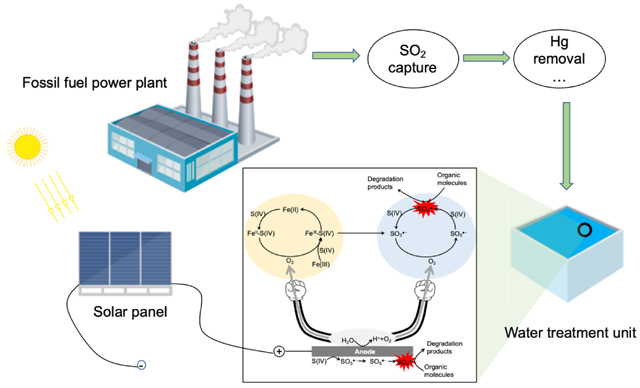

4. Possible procedures to realize the proposed energy-water-environment nexus

The electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process has been demonstrated to effectively treat water contaminants, with sulfite to represent the pure and aqueous form of SO2. Other concerns to be considered are the capture and purification process of SO2, and the electricity source to power this process. Here we propose sequential procedures to realize this energy-water-environment nexus (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Schematic illustration of procedures to realize the proposed energy-water-environment nexus.

(1). Capture of SO2 from flue gas. SO2 can be captured and concentrated from the flue gas by alkaline solutions such as ammonia [58-60]. At this stage, most particulate matters are removed. Captured SO2 then enters the next step.

(2). Purification of captured SO2. Among all the hazards in flue gas, mercury poses the greatest ecological/health concern due to its toxicity. Well-established mercury removal techniques such as Thief process [61] or other processes [62,63] can be adopted. Other control processes are necessary if additional hazards are identified. At this stage, the captured SO2 is relatively clean and safe for water treatment.

(3). Solar panels to power electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process. Harnessing solar energy with a high efficiency has been well studied for the past few decades [64,65], and could be used to supply the power of electric equipment.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we manifested a novel energy-water-environment nexus, which is using waste SO2 from electricity energy production to alleviate water contamination. As a demonstration, an electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process was used to degrade ibuprofen contaminant using both synthetic water and field water matrices. The excellent water treatment efficiency of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process is due to following synergetic mechanisms: 1) anode-induced acid zone facilitates Fe(II)/sulfite process; 2) electrolytic oxygenation supports the “bi-cycle” of sulfite evolutions; and 3) sulfite oxidation on anode generates oxysulfur radicals for contaminant degradation. The strong potential of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process was further demonstrated by non-selective degradation of various recalcitrant contaminants and effectiveness in highly carbonated media. Feasibility and energetic analysis were performed to indicate the advantages of this process. It is believed that the tens of millions of tons SO2 “waste” holds numerous chemical energy for primary water treatment. Implications of this energy-water-environment nexus are significant: SO2 mitigation and sustainable water treatment are simultaneously achieved.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Achieved simultaneous sulfur dioxide mitigation and water contaminant treatment

Synergy mechanism of electro/Fe(II)/sulfite process was investigated

Feasibility and energetic analysis indicated it is a viable process

Procedures to realize the energy-water-environment nexus were proposed

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institute of Health (Grant No. P42ES017198). The authors thank Yunfei Xue, Feng Wu, Tao Luo, Zhenhua Wang, Dongqi Wang, and Fernando Pantoja-Agreda for assistance with experiments including electron spin resonance, test of different substrates, HPLC-MS analysis, and groundwater extraction. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sources.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Wang Z, Wang J, Lan C, He I, Ko V, Ryan D, Wigston A. A study on the impact of SO2 on CO2 injectivity for CO2 storage in a Canadian saline aquifer. Appl Energy 2016;184:329–36. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lv Y, Yu X, Tu ST, Yan J, Dahlquist E. Experimental studies on simultaneous removal of CO2 and SO2 in a polypropylene hollow fiber membrane contactor. Appl Energy 2012;97:283–8. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Klimont Z, Smith SJ, Cofala J. The last decade of global anthropogenic sulfur dioxide: 2000–2011 emissions. Environ Res Lett 2013;8(1):014003. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rui Z, Cui K, Wang X, Chun J, Li Y, Zhang Z, Lu J, Chen G, Zhou X., Patil, S. A comprehensive investigation on performance of oil and gas development in Nigeria: Technical and non-technical analyses. Energy 2018;158:666–80. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jiang J, Rui Z, Hazlett R, Lu J. An integrated technical-economic model for evaluation CO2 enhanced oil recovery development. Appl Energy 2019;247:191–211. [Google Scholar]

- [6].De Blasio C, Mäkilä E, Westerlund T. Use of carbonate rocks for flue gas desulfurization: Reactive dissolution of limestone particles. Appl Energy 2012;90(1):175–81. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Heidel B, Hilber M, Scheffknecht G. Impact of additives for enhanced sulfur dioxide removal on re-emissions of mercury in wet flue gas desulfurization. Appl Energy 2014;114:485–91. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee YJ, Rochelle GT. Oxidative degradation of organic acid conjugated with sulfite oxidation in flue gas desulfurization: Products, kinetics, and mechanism. Environ Sci Technol 1987;21(3):266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhou D, Chen L, Li J, Wu F. Transition metal catalyzed sulfite auto-oxidation systems for oxidative decontamination in waters: a state-of-the-art minireview. Chem Eng J 2018;346:726–38. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen L, Peng X, Liu J, Li J, Wu F. Decolorization of Orange II in aqueous solution by an Fe(II)/sulfite system: replacement of persulfate. Ind Eng Chem Res 2012;51(42):13632–8. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yu Y, Li S, Peng X, Yang S, Zhu Y, Chen L, Wu F, Mailhot G. Efficient oxidation of bisphenol A with oxysulfur radicals generated by iron-catalyzed autoxidation of sulfite at circumneutral pH under UV irradiation. Environ Chem Lett 2016;14(4):527–32. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen L, Huang X, Tang M, Zhou D, Wu F. Rapid dephosphorylation of glyphosate by Cu-catalyzed sulfite oxidation involving sulfate and hydroxyl radicals. Environ Chem Lett 2018; 16(4): 1507–11. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen L, Luo T, Yang S, Xu J, Liu Z, Wu F. Efficient metoprolol degradation by heterogeneous copper ferrite/sulfite reaction. Environ Chem Lett 2018; 16(2):599–603. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chen L, Tang M, Chen C, Chen M, Luo K, Xu J, Zhou D, Wu F. Efficient bacterial inactivation by transition metal catalyzed auto-oxidation of sulfite. Environ Sci Technol 2017;51(21): 12663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bakalowicz M Water chemistry of some karst environments in Norway. Nor Geogr Tidsskr 1984;38(3-4):209–14. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ashraf MA, Maah MJ, Yusoff I. Water quality characterization of varsity lake, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Chem 2010;7(S1):S245–S254. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yuan Y, Yang S, Zhou D, Wu F. A simple Cr(VI)–S(IV)–O2 system for rapid and simultaneous reduction of Cr(VI) and oxidative degradation of organic pollutants. J Hazard Mater 2016;307:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Qiang Z, Chang JH, Huang CP. Electrochemical generation of hydrogen peroxide from dissolved oxygen in acidic solutions. Water Res 2002;36(1):85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yu F, Zhou M, Zhou L, Peng R. A Novel Electro-Fenton Process with H2O2 Generation in a Rotating Disk Reactor for Organic Pollutant Degradation. Environ Sci Technol Lett 2014; 1(7), 320–4. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lu J, Dreisinger DB, Cooper WC. Anodic oxidation of sulphite ions on graphite anodes in alkaline solution. J Appl Electrochem 1999;29(10): 1161–70. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Buser HR, Poiger T, Müller MD. Occurrence and environmental behavior of the chiral pharmaceutical drug ibuprofen in surface waters and in wastewater. Environ Sci Technol 1999;33(15):2529–35. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yuan SH, Chen MJ, Mao XH, Alshawabkeh AN. A three-electrode column for Pd-catalytic oxidation of TCE in groundwater with automatic pH-regulation and resistance to reduced sulfur compound foiling. Water Res 2013;47:269–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zelinsky AG, Pirogov BY. Electrochemical oxidation of sulfite and sulfur dioxide at a renewable graphite electrode. Electrochim Acta 2017;231:371–8. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brevett CAS, Jonson DC. Anodic oxidations of sulfite, thiosulfate, and dithionite at doped PbO2-film electrodes. J Electrochem Soc 1992;139:1314–9. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Huie RE, Neta P. The chemical behavior of SO3•− and SO5•− radicals in aqueous solutions. J Phys Chem 1984, 88, 5665–9. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Quijada C, Vázquez JL. Electrochemical reactivity of aqueous SO2 on glassy carbon electrodes in acidic media. Electrochim Acta 2005;50:5449–57. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tolmachev YV, Scherson DA. The electrochemical oxidation of sulfite on gold: UV–vis reflectance spectroscopy at rotating disk electrode. Electrochim Acta 2004;49:1315–9. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ranguelova K, Bonini MG, Mason RP. (Bi)sulfite oxidation by copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase: sulfite-derived, radical-initiated protein radical formation. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118(7):970–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mottley C, Mason RP. Sulfate anion free radical formation by the peroxidation of (bi)sulfite and its reaction with hydroxyl radical scavengers. Arch Biochem Biophys 1988;267(2):681–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Neta P, Huie RE. Free-radical chemistry of sulfite. Environ Health Perspect 1985;64:209–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Deister U; Warneck P Photooxidation of sulfite (SO32−) in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem 1990;94(5):2191–8. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhou D, Yuan Y, Yang S, Gao H, Chen L. Roles of oxysulfur radicals in the oxidation of Acid Orange 7 in the Fe(III)—sulfite system. J Sulfur Chem 2015;36(4):373–84. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Neta P; Huie RE One-electron redox reactions involving sulfite ions and aromatic amines. J Phys Chem 1985;89(9):1783–7. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Eibenberger H, Steenken S, O'Neill P, Schulte-Frohlinde D. Pulse radiolysis and electron spin resonance studies concerning the reaction of SO4•− with alcohols and ethers in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem 1978;82(6):749–50. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Anipsitakis GP, Dionysiou DD, Gonzalez MA. Cobalt-mediated activation of peroxymonosulfate and sulfate radical attack on phenolic compounds. Implications of chloride ions. Environ Sci Technol 2006;40(3):1000–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kwon M, Kim S, Yoon Y, Jung Y, Hwang TM, Lee J, Kang JW. Comparative evaluation of ibuprofen removal by UV/H2O2 and UV/S2O82− processes for wastewater treatment. Chem Eng J 2015;269:379–90. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sabri N, Hanna K, Yargeau V. Chemical oxidation of ibuprofen in the presence of iron species at near neutral pH. Sci Total Environ 2012;427:382–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Caviglioli G, Valeria P, Brunella P, Sergio C, Attilia A, Gaetano B. Identification of degradation products of ibuprofen arising from oxidative and thermal treatments. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2002;30(3):499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Grirrane A, Corma A, Garcia H. Gold-catalyzed synthesis of aromatic azo compounds from anilines and nitroaromatics. Science 2008;322(5908):1661–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kramer MS, Naimark LE, Roberts-Bräuer R, McDougall A, Leduc DG. Risks and benefits of paracetamol antipyresis in young children with fever of presumed viral origin. Lancet 1991;337(8741):591–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Le Marechal AM, Križanec B, Vajnhandl S, Valh JV. Textile finishing industry as an important source of organic pollutants. In Organic pollutants ten years after the Stockholm convention-environmental and analytical update 2012. InTech. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Glaze WH, Kang JW, Chapin DH. The Chemistry of Water Treatment Processes Involving Ozone, Hydrogen Peroxide and Ultraviolet Radiation. Ozone Sci Eng 1987;9:335–52. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kumar A, Bisht BS, Joshi VD, Singh AK, Talwar A. Physical, chemical and bacteriological study of water from rivers of Uttarakhand. J Hum Ecol 2010;32:169–73. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mishra VS, Mahajani VV, Joshi JB. Wet air oxidation. Ind Eng Chem Res 1995;34(1):2–48. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Levee J, Pintar A. Catalytic wet-air oxidation processes: a review. Catal Today 2007;124(3-4): 172–84. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zularisam AW, Ismail AF, Salim R. Behaviours of natural organic matter in membrane filtration for surface water treatment—a review. Desalination 2006; 194(1-3):211–31. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Oiler I, Malato S, Sánchez-Pérez J. Combination of advanced oxidation processes and biological treatments for wastewater decontamination—a review. Sci Total Environ 2011;409(20):4141–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].US industrial electricity price. https://www.rockymountainpower.net/about/rar/ipc.html, 2019. [accessed on March 15, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Neyens E, Baeyens J. A review of classic Fenton’s peroxidation as an advanced oxidation technique. J Hazard Mater 2003;98(1-3):33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Babuponnusami A, Muthukumar K. A review on Fenton and improvements to the Fenton process for wastewater treatment. J Environ Chem Eng 2014;2(1):557–72. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hsueh CL, Huang YH, Wang CC, Chen CY. Degradation of azo dyes using low iron concentration of Fenton and Fenton-like system. Chemosphere 2005;58(10):1409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hydrogen peroxide price. https://www.kemcore.com/hydrogen-peroxide-50.html; 2019. [accessed 15 April 2019].

- [53].Carra I, Ortega-Gómez E, Santos-Juanes L, López JLC, Pérez JAS. Cost analysis of different hydrogen peroxide supply strategies in the solar photo-Fenton process. Chem Eng J 2013;224:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Silva TF, Fonseca A, Saraiva I, Boaventura RA, Vilar VJ. Scale-up and cost analysis of a photo-Fenton system for sanitary landfill leachate treatment. Chem Eng J 2016;283:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- [55].dos Santos Napoleão DA, Cezar FS, Filho HJH, Siqueira AF. Economic analysis of Fenton process in the slurry treatment. IOSR-JESTFT 2017;11(8):12–6. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Tran QK, Schwabe KA, Jassby D. Wastewater reuse for agriculture: development of a regional water reuse decision-support model (RWRM) for cost-effective irrigation sources. Environ Sci Technol 2016;50(17):9390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].McGuire MJ, Blute NK, Qin G, Kavounas P, Froelich D, Fong L. Hexavalent chromium removal using anion exchange and reduction with coagulation and filtration. Water Res Found Proj #3167., 2007, p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gao X, Ding H, Du Z, Wu Z, Fang M, Luo Z, Cen K. Gas–liquid absorption reaction between (NH4)2SO3 solution and SO2 for ammonia-based wet flue gas desulfurization. Appl Energy 2010;87(8):2647–51. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Qi G, Wang S. Thermodynamic modeling of NH3-CO2-SO2-K2SO4-H2O system for combined CO2 and SO2 capture using aqueous NH3. Appl Energy 2017; 191:549–58. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Li K, Yu H, Qi G, Feron P, Tade M, Yu J, Wang S. Rate-based modelling of combined SO2 removal and NH3 recycling integrated with an aqueous NH3-based CO2 capture process. Appl Energy 2015;148:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- [61].O’Dowd WJ, Pennline HW, Freeman MC, Granite EJ, Hargis RA, Lacher CJ, Karash A. A technique to control mercury from flue gas: the Thief process. Fuel Process Technol 2006;87(12):1071–84. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Heidel B, Rogge T, Scheffknecht G. Controlled desorption of mercury in wet FGD waste water treatment. Appl Energy 2016;162:1211–7. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Heidel B, Hilber M, Scheffknecht G. Impact of additives for enhanced sulfur dioxide removal on re-emissions of mercury in wet flue gas desulfurization. Appl Energy 2014;114:485–91. [Google Scholar]

- [64].O'Shaughnessy E, Cutler D, Ardani K, Margolis R. Solar plus: A review of the end-user economics of solar PV integration with storage and load control in residential buildings. Appl Energy 2018;228:2165–75. [Google Scholar]

- [65].O'Shaughnessy E, Cutler D, Ardani K, Margolis R. Solar plus: Optimization of distributed solar PV through battery storage and dispatchable load in residential buildings. Appl Energy 2018;213:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Neal C Alkalinity measurements within natural waters: towards a standardised approach. Sci Total Environ 2001;265:99–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.