THE RISKS

On December 8, 2019, the first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in Wuhan, China (1). Within 2 months, an estimated 1,716 Chinese healthcare workers were infected by COVID-19. Risk factors included close proximity to the virus, long work hours, poor hand hygiene, and improper or inadequate use of personal protective equipment (2). It is realistic to expect similar rates of infection among healthcare workers in other countries.

Most hospital guidelines recommend a healthcare provider stay home from work only if the provider manifests a fever. Research from Wuhan, China, demonstrated that although fever was a major symptom of COVID-19, only 43.8% of patients had fevers on admission. Other less-specific symptoms included dry cough (67.7%), fatigue (38.1%), myalgia and arthralgia (14.8%), headache (13.6%), and diarrhea (3.7%) (3). This suggests that the screening methods currently used by many hospitals might not have a robust sensitivity, and institutions must quickly broaden screening practices.

THE CULTURE

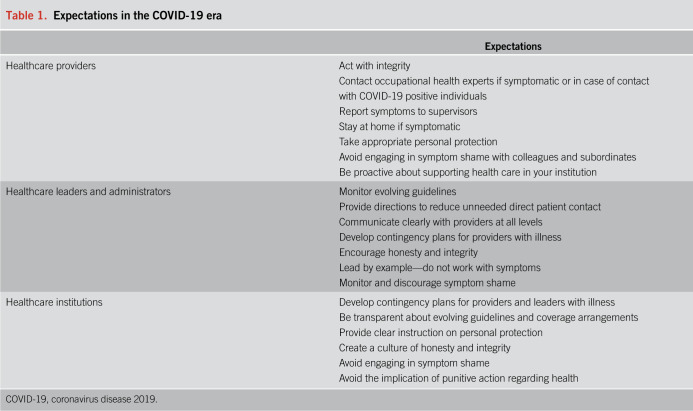

Healthcare providers, similar to firefighters, police officers, and military service personnel, have a culture of valuing duty and self-sacrifice. A survey of >800 physicians found that 83.1% had worked while sick within the past year. Of these, 95.3% recognized that presenteeism put patients at risk, and 98.7% reported that they continued to work to avoid burdening colleagues. Staffing concerns (94.9%), patient concerns (92.5%), and fear of ostracism by colleagues (64.0%) were other major contributors to their decisions (4). Similarly, 150 resident physicians were surveyed, and at least 51% reported working while sick within the previous year (5). Medical house staff, at the bottom of the physician hierarchy, look to senior physicians for guidance but are wary of punitive action against them and lack of transparency from leadership. Consequently, it is not unusual to encounter healthcare providers in offices and hospitals with upper respiratory symptoms. Often, administrators tacitly turn a blind eye to this practice. However, a sick healthcare provider with COVID-19 puts an entire work group at risk (Table 1).

Table 1.

Expectations in the COVID-19 era

THE SHAME

Optimally, healthcare providers with upper respiratory symptoms will recognize that they might have contracted COVID-19 and self-isolate. However, several barriers discourage healthcare providers from accepting and reporting COVID-19 symptoms. One of these barriers is “symptom shame” i.e., emotional discomfort caused by missing work owing to personal illness. Symptom shame can be self-imposed or externally imposed. A prevailing concern during the COVID-19 crisis is that symptom shame will not be vigorously discouraged to reduce the burden of replacing healthcare providers within a system that chronically lacks reserves.

Current estimates suggest that the basic reproductive number (R0) of COVID-19 is twice that of the seasonal influenza (6). Despite concern that COVID 19 is more infectious than the typical upper respiratory viruses, messages sent to healthcare providers have not changed consistently. In the early days of the virus, some providers were chastised for requesting quarantine after exposure to patients suspected to have the virus. When medical institution travel bans were introduced, providers were warned that if they traveled in violation of the ban and became infected, quarantine time might involve vacation days, sick leave, or leave without pay. This punitive policy might have had the unintended consequence of discouraging reporting of travel and virus symptoms. The policy was a manifestation of symptom shaming.

At the other end of the spectrum, some providers might have feigned illness to get time off or to limit exposure to COVID-19. Although uncommon, that practice is as detrimental as symptom shaming. Healthcare providers must be candid with administrators. Since many outpatient appointments have been canceled, patients have been funneled to the emergency department for non-life-threatening symptoms and COVID-19. There is an increasing need for healthy providers.

A CHANGE

The COVID-19 crisis highlights the need for change within the culture of medicine. Where possible, official documents and actions should urge providers to report symptoms and avoid presenteeism. Administrators should create contingency plans for emergencies, maintain a robust pool of reserve providers, and establish transparent coverage plans for sick providers. There must be open communication between individual providers and administrators, which allows for airing of concerns and system adjustments. Providers must be honest with themselves and their employers to protect their patients and colleagues.

The United Kingdom's National Health Service policy at baseline discourages providers with respiratory tract infections from working. Their current guidelines recommend that physicians remain at work after contact with a patient with COVID-19 but self-isolate if they develop symptoms or have a prolonged exposure to a positive household member. The United States should also use symptoms and family member positivity as triggers for COVID-19 testing and absence from work.

Enfranchising healthcare professionals who have low-grade symptoms to miss work will decrease the workforce in the short-term, but longer-term benefits will be profound. Providers who are not seriously ill will be able to return to work quickly. Providers quarantined with low-grade symptoms might be able to work from home and provide health care by telemedicine. Providers with more serious symptoms will avoid spreading the contagion to their coworkers. Healthcare administrators and leaders have an important role to encourage transparency and lead by example. The end goal is to increase sensitivity over specificity. Importantly, this will encourage a culture of honesty and integrity, which should endure even after the pandemic has passed.

The current pandemic is not the time for a healthcare provider to be sent home because they are too sick. Far from this, providers should be empowered to avoid working if they judge themselves to be sick. Healthcare administrators and leaders should ensure the resiliency of the work environment so that providers can elect to work from home with confidence that they will not be subject to symptom shame.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Michael G. Daniel, MD.

Specific author contributions: Wrote the article.

Financial support: None to report.

Potential competing interests: None to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang C, Liu L, Hao X, et al. Evolving epidemiology and impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. medRxiv 2020. 10.1101/2020.03.03.20030593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ran L, Chen X, Wang Y, et al. Risk factors of healthcare workers with corona virus disease 2019: A retrospective cohort study in a designated hospital of Wuhan in China. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382(18):1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szymczak J, Smathers S, Hoegg C, et al. Reasons why physicians and advanced practice clinicians work while sick. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169(9):815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jena A, Meltzer D, Press V, et al. Why physicians work when sick. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(14):1107–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, et al. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26(7). 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]