Iran is struggling to control COVID-19 between difficult public health decisions and persistent international sanctions. Priya Venkatesan reports.

Following the first reports of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections and the first reported death from COVID-19 in China in January, 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected most countries around the world, but some disproportionately more than others. One of the hardest-hit in the early stages of the pandemic was Iran. Two deaths due to COVID-19 were confirmed in Iran in the city of Qom on Feb 19, 2020, and despite an official announcement of the outbreak in the country by the government, Iran struggled to contain the virus, leading to a rapid spread to all 31 provinces by Mar 5, and 3294 deaths by Apr 3, facing “the hardest consequences of COVID-19 among the 22 countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region”, according to Amirhossein Takian (Department of Global Health & Policy, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran).

In the subsequent months, however, the government apparently had the virus under control, and began relaxing lockdown measures from early April. All went quiet from Iran until the beginning of June, 2020, when the media reported a worrying sharp increase in the number of COVID-19 cases that mirrored March's peak levels: 3574 new infections in 24 hours as of Jun 3. WHO reports a total of 171 789 cases of COVID-19 and 8281 deaths in Iran (with more than 200 deaths in the preceding 4 days) as of Jun 8. Iran, seemingly, has been catapulted into a second wave of disease.

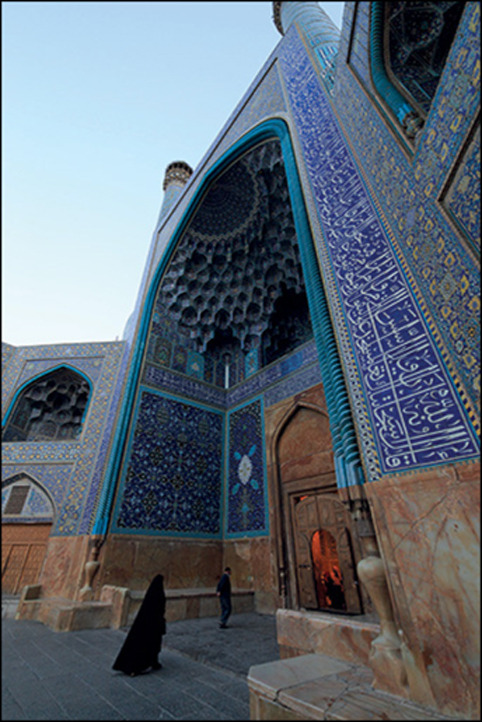

The reasons behind Iran's second wave of infections are myriad, but some experts feel they reflect poor decisions on the part of the country's officials to relax lockdown measures too early. Kamiar Alaei (Institute for International Health and Education, Albany, NY, USA) points out examples of poor policy making in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the high numbers of religious pilgrimages to holy Iranian shrines from other countries in the Middle East that were allowed to continue through February despite the high infection rate, as well as continued travels to and from China. Additionally, Alaei suggests that early reports of cases were dismissed by the government, since “officials didn't want people to be discouraged from participating in upcoming political events [including] the parliamentary election on Feb 20”. It seems that a lack of judgment regarding the pandemic is continuing. In early May, the government reopened Iran's mosques, against medical advice and despite other countries such as Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates keeping their mosques closed. As feared, the number of infections and deaths started to rise steeply a few weeks later, increasing from 2023 new cases and 34 deaths reported on May 25 to 2979 new cases and 81 deaths reported on June 1. Alaei says “Iran didn't learn from its initial poor decisions, which [has] resulted in making the situation worse. The minister of health announced prematurely on May 17 that the government had been able to control COVID-19. This message gave a false assurance to most people, [as] reopening all mosques in Iran would put more people at risk of exposure”.

Another factor that played a role in prompting the premature lifting of Iran's lockdown is the imposed US economic sanctions that have continued throughout the pandemic. Financial resources are extremely restricted in Iran, many people have lost their incomes due to the pandemic, and the government is unable to compensate them. Additionally, Iran cannot import necessary medical goods from any other country because of the sanctions, which adds a further strain to their health-care system—hitting the country with the “double burden of [the] epidemic and US unilateral sanctions”, according to Takian. He, however, takes the view that the country's health system has functioned reasonably well in combating the crisis. Despite infections rising, in an attempt to bolster the weakened economy, authorities have been progressively lifting restrictions throughout Iran, and most shops, mosques, schools, and offices are now open, albeit with distancing measures advised that many people are disregarding.

Other experts agree that US sanctions are certainly a major contributor to the worsening situation in Iran. Mahmoud Reza Pourkarim (KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Health Policy Research Center, Institute of Health, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran) commented “Iran is fighting two battles. [US] economic sanctions have made COVID-19 much more deadly, and US embargos have [impacted] the economies of both Iranian families and Iran's health-sector budget, which is the front line of combat against the current pandemic”.

The second spike in infections is expected to occur in Iran in the next few weeks following a long weekend at the start of June. Perhaps one measure to alleviate the forthcoming additional strain on the nation's resources and health infrastructure could be a temporary lifting of sanctions on medical supplies, in a humanitarian deal to prevent a future disaster for the country. Sadly the intersection of political interests and public health needs has proven to be a major obstacle to the control of COVID-19 in Iran as in other countries.

© 2020 Flickr – Valerian Guillot