There has been significant media attention and a New York City Health Alert [1] surrounding “Pediatric Multi-System Inflammatory Syndrome Potentially Associated with COVID-19.” As of May 18, 2020, there were 145 suspected cases of this syndrome in New York City [2]. While this disease has been outlined as having components shock and similarities to Kawasaki disease, associated neurologic manifestations have not been described (https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/COVID-19-Paediatric-multisystem-%20inflammatory%20syndrome-20200501.pd). We have encountered several children with this condition and highlight two with major neurological complications.

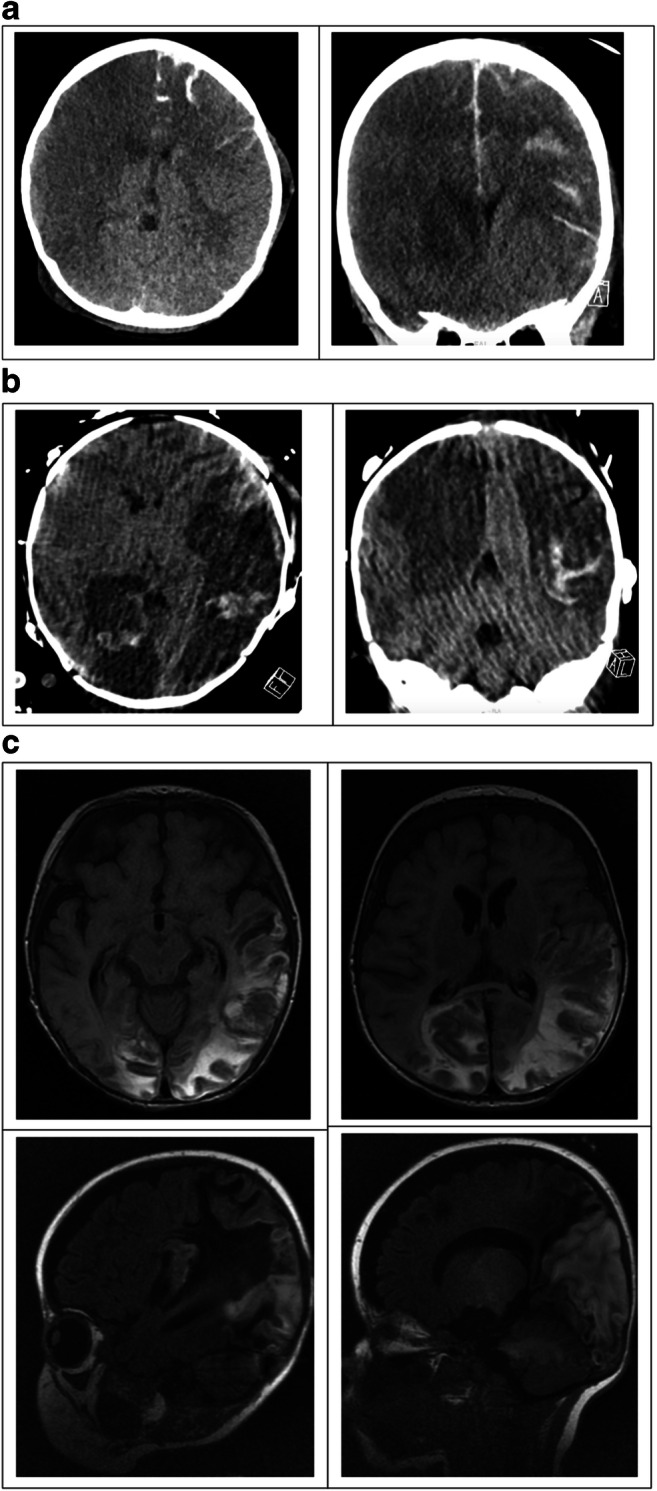

A 5-year-old boy with no significant past medical history presented with several days of fever, cough, and abdominal pain. He progressed to cardiogenic shock and transfer to our institution, where he tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies and had high IL-6 levels. He developed cardiopulmonary failure requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). After 5 days of ECMO, he was found to have a fixed and dilated right pupil. His heparin was emergently reversed, he was decannulated, and emergent CT head revealed a right middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarction, cerebral edema, and diffuse contralateral subarachnoid hemorrhage (Fig. 1a). Following the CT scan, his left pupil became fixed and dilated. The reversal of his paralytic revealed absent brainstem reflexes and movement. Brain death was confirmed 3 days later following normalization of his electrolytes.

Fig. 1.

a Axial (left) and coronal (right) CT head imaging demonstrating right hemispheric infarction and diffuse left hemispheric subarachnoid hemorrhage. b Axial (left) and coronal (right) CT head imaging demonstrating bilateral MCA and PCA territory infarctions, bilateral hemispheric transformation. c Axial T2 flair (above) and sagittal T1 MR imaging demonstrating bilateral occipito-parietal evolving hemorrhagic infarctions, bilateral subdural collections

The second patient is a 2-month-old boy with a history of tracheomalacia requiring tracheostomy. He presented with respiratory failure, pneumomediastinum, and bilateral pneumothoraces. He developed refractory respiratory failure and was emergently placed on ECMO, on which he remained for 8 days. Despite the clinical picture and high IL-6 values, he tested negative for COVID-19 antibodies. Continuous electroencephalogram (cEEG) found the child to be in non-convulsive status epilepticus, which was controlled on four anti-seizure medications. Daily screening head ultrasounds were performed per ECMO protocol. On day 1 of ECMO, a head ultrasound demonstrated multifocal echogenicity suspicious for hemorrhage. A follow-up CT revealed bilateral MCA and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) territory infarctions with the hemorrhagic transformation (Fig. 1b). The patient continued to have poor seizure control, requiring several weeks of intermittent EEG placement and anti-epileptic medication titration, including phenobarbital and midazolam continuous infusions. Interval MRI revealing evolving hemorrhagic infarctions in bilateral occipito-parietal lobes, left temporal and left frontal lobes, and stable bilateral subdural collections, believed to be cardioembolic in etiology (Fig. 1c). His ventilator support is currently being weaned.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved worldwide, coagulopathy leading to cerebral infarction as a result of viral infection has been reported. A “sepsis-induced coagulopathy” has been proposed [3], as the virus binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on brain endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Little has been elucidated regarding the mechanism of end-organ damage in the inflammatory syndrome we are now seeing in children. Both of these children required ECMO, which is associated with high embolic stroke risk. The second child, however, experienced two strokes very early in his ECMO course, perhaps pointing to a different etiology. These cases highlight a need for further investigation into the hypercoagulable manifestations of this syndrome. While we continue to learn more, efforts to facilitate the identification of children with neurologic complications may allow targeted medical and surgical interventions to improve outcomes.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors report no direct conflict of interest in the current publication.

Disclaimer

This manuscript is a unique submission and is not being considered for publication, in part or in full, with any other source in any medium. This research has not previously been presented.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Daskalakis DCDC (2020) Pediatric Multi-System Inflammatory Syndrome Potentially ... Retrieved May 20, 2020, from https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/han/alert/2020/covid-19-pediatric-multi-system-inflammatory-syndrome.pdf?ftag=MSF0951a18

- 2.Russo M (2020) Up to 147 NYC Kids Sickened by Severe New COVID Syndrome; 15 Cases Confirmed in NJ. Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/cdc-confirms-link-of-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-to-covid-19-145-potential-cases-in-nyc/2421547/

- 3.Hess DC, Eldahshan W, Rutkowski E (2020) COVID-19-related stroke [published online ahead of print, 2020]. Transl Stroke Res 1–4. doi:10.1007/s12975-020-00818-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]