Abstract

Background:

Osteoarthritis is a long-term condition, and four core treatments are recommended to minimize the interference of pain and symptoms on their daily function. However, older Black Americans have traditionally been at a disadvantage in regard to knowledge of and engagement in chronic disease self-management and self-care. Surprisingly, minimal research has addressed understanding motivational factors key to self-management behaviors. Thus, it is important to understand if older Black Americans’ self-management is supported by current recommendations for the management of symptomatic osteoarthritis and what factors limit or motivate engagement in recommended treatments.

Objective:

Our objectives are to: (1) identify stage of engagement in four core recommended treatments for osteoarthritis, (2) describe the barriers and motivators to these recommended treatments, and (3) construct an understanding of the process of pain self-management motivation.

Design:

A mixed-methods concurrent parallel design.

Setting:

Participants were recruited from communities in northern Louisiana, USA.

Participants:

Black Americans (≥50 years of age) with clinical osteoarthritis and/or provider-diagnosed osteoarthritis were enrolled. One hundred ten participants completed the study, and 18 of these individuals were also interviewed individually.

Methods:

Data were collected using in-person surveys and interviews. Over a period of 11 months, close- and open-ended surveys and in-depth interviews were conducted with participants. Descriptive statistics describe utilization/engagement level as well as barriers and motivators of recommended treatments for non-surgical osteoarthritis. Content and thematic analyses of interviews summarized perspectives on the process and role of motivation in pain self-management.

Results:

Overall, engagement levels in treatments ranged from very low to high. Over 55% of older Black Americans were actively engaged in two of the recommended treatments: land-based exercise and strength training. Major motivators included reduction in pain and stiffness and maintenance of mobility and good health. The majority of participants were not using water-based exercise and self-management education. Primary barriers were lack of access, time, and knowledge of resources.

Conclusions:

In order to maximize the benefits of osteoarthritis pain self-management, older Black Americans must be equipped with the motivation, resources, information and skills, and time to engage in recommended treatment options. Their repertoire of behavioral self-management did not include two key treatments and is inconsistent with what is recommended, predominantly due to barriers that are difficult to overcome. In these cases, motivation alone is not optimal in promoting self-management. Providers, researchers, and community advocates should work collaboratively to expand access to self-management resources, particularly when personal and community motivation are high.

Keywords: Black americans, Chronic pain, Joints, Musculoskeletal pain, Older adults, Osteoarthritis, Self-management

1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders, such as osteoarthritis, account for a large proportion of physical disability and chronic pain worldwide (Global Burden of Disease 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2017). Osteoarthritis is the most common degenerative joint disease and is a long-term condition often characterized by the prototypical symptom of chronic pain. When osteoarthritis pain is not well-managed through professional care and self-management, inescapable consequences include physical disability, loss of quality of and satisfaction with life, and healthcare expenses surpassing costs for heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Thus, chronic musculoskeletal pain poses a serious global health concern across all demographics (Blyth et al., 2019) but is rather disabling in under-served racial minorities in the U.S., such as Black Americans (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Bazargan et al., 2016).

Black-White racial disparities in chronic pain, disability outcomes, and psychosocial health among adults with osteoarthritis are persistent (Vaughn et al., 2019; Vina et al., 2018; Flowers et al., 2019). Despite the overwhelming impact of chronic pain, Black patients are less likely to receive pain screenings (Burgess et al., 2013), receive comprehensive pain services that could mitigate the symptomatic and debilitating effects of osteoarthritis (Dobscha et al., 2009), or participate in self-management programs and coping skills training (Townley et al., 2010; Mingo et al., 2013; Allen et al., 2018). Subsequently, ineffective self-management threatens to exacerbate racial/ethnic disparities and continued poor outcomes in long-term conditions like osteoarthritis. Given the systemic disregard for severe chronic pain and its subsequent inadequate treatment among Black Americans across the adult lifespan and long-term conditions, a recent nursing editorial called for greater attention to pain-related disparities (Vallerand, 2018). Ironically still, most research does not systematically study the factors that might enhance or interfere with older Black Americans’ ability to implement treatment options and integrate these into a consistent self-management plan. Therefore, it is important to identify potentially modifiable cognitive, behavioral, and personal barriers and motivators that impact older Black Americans’ utilization and adherence to treatment recommendations for the self-management of non-surgical osteoarthritis. This gap in the scientific literature poses a challenge in understanding to what extent and why older Black Americans’ current self-management strategies do or do not align with recommended osteoarthritis treatments.

Although conceptually distinct, studies have used evolving terminology to describe similar behaviors and the personal process of (self)managing osteoarthritis and pain: self-care (Albert et al., 2008; Ibrahim et al., 2001; Silverman et al., 2008), self-help care (Newman, 2001), coping (Golightly et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2008), self-treatment (Peat and Thomas, 2009), or treatments (Bill-Harvey et al., 1989). The term ‘self-management’ is used throughout this paper given the study’s conceptualization and explicit exploration into disease (i.e., osteoarthritis) and symptom (i.e., pain) self-management. Self-management is a broad term that describes the range of interventions and processes that an individual actively engages in to manage a chronic disease and its subsequent symptoms and consequences in their daily life (Grey et al., 2015).

2. Background

2.1. Barriers and motivators to recommended core osteoarthritis treatments

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends five core behaviors for the management of osteoarthritis: land-based exercise, water-based/aquatic exercise, strength training, weight management, and self-management programs and education (McAlindon et al., 2014). These behaviors are also recommended by American College of Rheumatology (Hochberg et al., 2012) for symptomatic osteoarthritis across joint locations. There is general agreement across guidelines supporting these core treatments as effective strategies in reducing pain when incorporated into daily self-management routines (McAlindon et al., 2014; Hochberg et al., 2012; Fibel et al., 2015). Yet, many of the recommended self-management behaviors lack validation in Black Americans; therefore, the patterns of utilization and the efficacy of these recommended treatments are unknown. One recent study found that older Black Americans use a common set of pharmacological and self-management strategies to manage osteoarthritis pain, and exercise (land-based/aerobic) and strength training/stretching were the only two consistently used strategies that are supported by treatment guidelines (Booker et al., 2018).

One of the challenges to implementation of recommended treatments is ensuring that older Black Americans have full access to offer appropriate services. Self-management can be supported or limited by a number of existing factors, and there is minimal research from which to glean barriers and motivators to the recommended core treatments of interest to this study. Barriers can be experienced at the personal, system, and provider levels, and can explain a lower utilization of treatment options especially by minority and disadvantaged groups. For example, only 2% of Black Americans at high risk for or with knee osteoarthritis met physical activity guidelines as compared to 13% of Caucasian Americans (Song et al., 2013). This is consistent with reported lower rates of exercise utilization independent of pain intensity in older Black Americans (Grubert et al., 2013). Lower rates of exercise could likely be due to insufficient information about appropriate types, frequency, and amount of exercise (Park, Hirz, et al., 2013). Older Black Americans have even suggested adding time for guided exercises during self-management program classes (Parker et al., 2012), which might mitigate associated barriers related to embarrassment/self-consciousness and fear of re-injury or exacerbating pain (Park, Hirz, et al., 2013).

A major criticism of osteoarthritis research is the underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities in trials testing behavioral interventions (McIlvane et al., 2008; Reid et al., 2008). Compounding this issue is the lack of insight on the barriers and motivators to engaging in recommended treatments or other behavioral interventions. It may be that the barrier-to-motivator ratio is imbalanced, whereby greater or more complex barriers than motivators exist, contributing to the treatment disparities and poor outcomes reported in the literature. This is why additional research on the motivations that drive selection and use of self-care behaviors for osteoarthritis in Black American and Caucasian older adults is justified (Silverman et al., 2008).

2.2. Barriers and motivators to chronic pain self-management

Several studies identify similar barriers and motivators that generally impact older adults’ chronic pain self-management behaviors (Austrian et al., 2005; Kawi, 2013; Park, Hirz, et al., 2013). Example motivators for chronic pain self-management in ethnically diverse older adults are adequate social support, available resources, and having a positive attitude (Park, Hirz, et al., 2013). Older Black Americans’ social network is an integral facet of pain self-management and respected source of emotional and informational support for treatment decisions (Fiargo et al., 2005; Ibrahim et al., 2001; Martin et al., 2012).

Reported barriers to chronic pain management in older adults are lack of motivation and self-efficacy, and social support; unavailability/inaccessible treatments; decreased faith in the effectiveness of treatments/history of failed treatments; challenging patientphysician interactions; inadequate education from providers; and psychosocial issues (depression, fear of pain or re-/injury, and anxiety) (Kawi, 2013; Park, Hirz, et al., 2013; Booker et al., 2018). Motivation and desire are necessary for change (Ryan, 2009), and more empirical studies are needed to address and understand how motivation translates into action for pain management (Eccles et al., 2012; Park, Hirz, et al., 2013; Silverman et al., 2008). Our study addresses a gap in understanding the experience and role of motivation in readiness to engage in recommended treatment options for osteoarthritis and in systematically identifying barriers and motivators that influence said engagement. Such inquiries will allow us to better help Black older adults perform osteoarthritis pain self-management.

2.3. Theoretical underpinnings

Self-management is an essential approach to manage chronic pain associated with osteoarthritis because it permits individuals to develop a tailored routine that meets their self-care needs. The caveat, however, is that older adults must be aware of motivations and beliefs, empowered, responsible, and willing to take an active role in pain management (Stewart et al., 2014). According to the Motivational Model of Pain Self-Management, motivation is needed to manage, cope, adapt and maintain pain self-management behaviors (Jensen et al., 2003, 2004); thus motivation is a key pre-requisite for readiness to and/or actual engagement in self-management behaviors and health behavior change (Ryan and Sawin, 2009; Jensen et al., 2003). In fact, motivation is one predisposing factor associated with using non-pharmacological pain self-management (Park, Hirz, et al., 2013).

A tenet of the Motivational Model of Pain Self-Management, which draws on the construct of readiness to change from the Transtheoretical Model of Change, is that pain self-management is impacted by many factors including perceived barriers (Jensen et al., 2004). Self-care motivation in older adults may be restricted by physical and cognitive capacity to make decisions and to followthrough with intended or recommended behaviors (Dattalo et al., 2012; Mittler et al., 2013). Shively et al. (2013) indicates that motivation along with information and skills are necessary for self-management of chronic illness. Similarly, Riegel and colleague’s Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness clearly positions motivation as a factor that affects self-care, particularly for treatment initiation and adherence (Riegel et al., 2019). Often symptoms motivate individuals to engage in self-care or self-management as well as utilize healthcare resources (Riegel et al., 2019). For older Black Americans, symptom severity and its subsequent restriction on function were strong drivers of pain self-management (Booker et al., 2018). In contrast, others suggest that motivation is a proximal outcome of self-management rather than a criterion for self-management (Grey et al., 2015). Our study posited that motivation is both a predisposing factor and an outcome resulting in a recursive, mutually reinforcing relationship that stimulates engagement in and maintenance of self-management. Whether situated as an antecedent factor or intermediate outcome, motivation is a core construct in chronic disease self-management, and the lack thereof can serve as a barrier to pain self-management.

2.4. Aims

The Transtheoretical Model of Change, Social Cognitive Theory, Theory of Planned Behavior, and The Information-Motivation- Behavior theory account for 63% of all behavior theories used in arthritis and chronic low back pain self-management programs (Keogh et al., 2015). Still, the number of studies investigating how culture informs readiness to change/engage, motivation, and behavioral pain self-management in various racial sub-groups of older adults remain limited. Drawing from the Transtheoretical Model of Change and the Motivational Model of Pain Self-Management, our study aimed to (1) identify stage of engagement in four core recommended treatments for OA, (2) describe the barriers and motivators to these recommended treatments, and (3) construct an understanding of motivation to manage osteoarthritis and associated chronic pain. This study expands current knowledge by embedding the data collection and analysis within motivation and behavior change frameworks that help inform practice, policy, and future research. We have previously published on the general self-management strategies that are used by older Black Americans (Booker et al., 2018), and this paper provides new data examining the recommended treatments for the self-management of osteoarthritis and the motivations to use or not use these treatments.

3. Methods

3.1. Study design and participants

In a community-based, convenience sample of older Black Americans, this mixed methodology study used descriptive cross- sectional surveys to gather quantitative data (Total N = 110), and open-ended survey questions (Subset N = 96) and individual in-depth interviews (Subset N = 18) to generate qualitative data. Purposive sampling, using pain severity, education, age, and gender as stratifying factors, was used to select interviewees from participants who completed the survey phase of the study.

3.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individuals were eligible to participate if they reported provider-diagnosed osteoarthritis and/or presented with symptomatic osteoarthritis, chronic joint pain for at least three months, were aged 50 years or older, identified as Black American or African American, and were without evidence of major cognitive impairment. To meet the osteoarthritis criterion, individuals had to report current joint symptoms with at least three of the following: pain, stiffness, swelling, and/or crepitus occurring in any major joint site. Exclusion criteria consisted of chronic conditions that would limit reporting (e.g., stroke or dementia) or confound understanding of osteoarthritis pain (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, sickle cell disease). Full details on sample enrollment and study methodology are presented elsewhere (Booker et al., 2018).

3.2. Ethical approval

Prior to data collection, ethical approval was granted by the University of Iowa IRB-02 Social Science/Behavioral program. Consent from participants was given by voluntarily completing the surveys during visit 1. During the consent process for visit 1, participants were offered the opportunity participate in a qualitative interview. By providing consent for visit 1, they provided verbal consent for re-contact to ask if they would like to participate in the qualitative interview. No participant refused to be re-contacted.

3.3. Data collection

Visit 1 consisted of participants completing paper-based, in- person surveys on pain self-management, demographics, and health and chronic pain history. Visit 2 invited 18 participants from visit 1 to complete a single one-on-one qualitative interview.

3.3.1. Engagement in recommended core treatments

Readiness to manage pain arose from Transtheoretical Model of Change which is a comprehensive, biopsychosocial model that conceptualizes the process of intentional behavior change using five stages of change: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (Prochaska and Velicer, 1997). Thus, the Pain Self-Management Engagement Questionnaire (PSMEQ) was designed specifically for this study to evaluate stage of engagement (i.e., pre-contemplation, etc.) and barriers and motivators to engagement in four recommended core treatments for management of non-surgical osteoarthritis: land-based exercise, water-based exercise, strength training, self-management programs and education (e.g., the Arthritis Self-Management Program). Although the core treatments of investigation were developed for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis, we were able to apply these criteria because 87% (N = 96) of our sample reported osteoarthritis in a weight-bearing joint primarily the knee (N 85, 77%).

We also asked about general motivation = with a single question, “On a scale of 0–10, how motivated are you to effectively manage your pain (0 = being not motivated and 10 being highly motivated)?” Content validity of the PSMEQ was =established by two experts with significant experience in geriatric pain and complementary pain treatment. The PSMEQ was designed with a FleschKincaid reading ease of 100.2 (i.e., 0 = is hardest to read and 100= easiest to read; 5th grade reading level; very easy to read).

3.3.2. Barriers and motivators to engagement in recommended core treatments

The PSMEQ also asked two open-ended questions to elicit barriers and motivators for each recommended treatment. Take land-based exercise for example, “What things prevent you from being able to exercise?”, and “What things help/motivate you to exercise?”

3.3.3. Experience of pain self-management motivation

To elucidate participants’ experience and beliefs about motivation for self-management, semi-structured, face-to-face qualitative interviews were conducted in participants’ place of residence/work or other quiet location by the same researcher [SB] to ensure consistency and dependability. A digital recorder captured participants’ verbal narratives and field notes also gathered additional data on observations and researcher thoughts. Interviews were designed to be 60 minutes, but actual time ranged from 37–90 minutes. An interview guide was used to facilitate robust discussions between the researcher and participant. Analyses for this paper were based on the following questions:

What do you to do keep arthritis pain from getting worse?

What things keep you from being able to manage your pain?

What things help you control your pain?

What do you think keeps aging Black Americans from managing their pain better?

What could we do to motivate our people manage their pain better?

What would help you increase your confidence to manage your osteoarthritis pain?

3.4. Data analysis

3.4.1. Statistical analysis

Recruitment, data collection, and data analysis occurred concurrently, and this procedural order is consistent with convergent, parallel mixed methods design which allows both quantitative and qualitative data to be generated and analyzed simultaneously (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011). Survey data was entered into an Excel spreadsheet, reviewed for coding accuracy, and imported into SPSS (version 25.0). Demographic and survey data were summarized using descriptive statistics: means with standard deviations and frequencies with percentages. Based on the distribution of responses across stages of engagement, the five stages were collapsed into three stages (pre-contemplation, preparation, and action) to allow for a clearer interpretation and to help to stabilize the variance in group size.

3.4.2. Content analysis

Because the open-ended questions on the PSMEQ were optional, response rate for each behavior varied, and 96 participants completed at least one of the open-ended questions describing their personal barriers and motivators. All responses were transcribed into Microsoft Excel (version 2016) for a summative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). After a thorough reading, responses were collated into categories, and each category included between 2 and 6 specific barriers and motivators for each recommended treatment. Frequencies were calculated for each major barrier and motivator reported, and an illustrative quote was chosen to represent a barrier and motivator for each recommended osteoarthritis treatment (see later Table 2). These complementary data are integrated with the qualitative analyses to demonstrate the level of engagement in each recommended treatment.

Table 2.

Barriers and motivators to recommended core treatments.

| Core treatment | Illustrative quotes | Motivator/barrier | Step in increasing motivation |

|---|---|---|---|

| “That’s my biggest problem. They say exercise. Say, when I get through exercisin’, I’m in pain. What am I supposed to do? What are the alternatives? They givin’ you exercise that’s talkin’ about walk. I can’t walk from here to there.” - 50 y/o female | Barrier | Modify negative attitudes | |

| “For arthritis pain; to keep moving and body in good shape.” (yoga, chair volleyball at senior center) - 71 y/o female | Motivator | Become self-disciplined | |

| “I have no access. Love to swim and probably the only Black man I know who skis and dives; would’ve gotten certified [as lifeguard] but reading/writing issues kept from excelling.” - 71 y/o male | Barrier | Keep positive attitude | |

| “It’s very beneficial because I really can move without hurting myself as opposed to doing land aerobics. It is enjoyful as well to move and have that release.” - 54 y/o female | Motivator | Keep positive attitude and become disciplined | |

| “I don’t really take the time.” - 75 y/o female | Barrier | Acknowledge lack of motivation | |

| “The exercise helps with the pain. The exercise helps me to walk and help with my balance.” - 81 y/o female | Motivator | Become disciplined | |

| No access; however, “To know how to manage something is a plus; not knowing will cause you to be in a whole lot of trouble than knowing” - 71 y/o male | Barrier | Communicate with others who care | |

| “It gives the tools that promotes a healthier life. Learn things for pain modification as well as things to help emotionally.” - 54 y/o female | Motivator | Communicate with others who care |

Abbreviation: y/o = year old.

3.4.3. Thematic analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded, and recordings were transcribed verbatim, verified, and coded using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six step framework. Data were managed using HyperRE- SEARCH qualitative software (version 3.7.3). A thematic analysis was applied to identify patterns and to construct an understanding of the process and influence of motivation on older Black American’s experience and performance of chronic pain self-management. After each interview, the researcher also typed the field notes as a method to help identify when thematic saturation was achieved. A systematic process was carried out by two researchers who coded transcripts iteratively during multiple qualitative retreats and consensus meetings to discuss and arbitrate differences in coding and/or interpretation.

3.4.4. Rigor and reflexivity

Care was taken to use participants’ language in order to reduce imposing author bias on the data. Trustworthiness in qualitative research (Lincoln and Guba, 1985) and legitimation in mixed-methods research (Onwuegbuzie and Johnson, 2006) was established through iterative engagement with the data. Credibility was ensured through (1) deliberate and a priori probes to deeply and accurately understand participants’ individual and cultural experiences, (2) triangulation of data sources and member-checking that provided feedback on the cultural relevance and accuracy of interpretation of data, and (3) bracketing and debriefing to identify researcher biases.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic description

Our sample was primarily women (81.8%) in later life (mean age = 68.44 years ± 12.4) and had lived with osteoarthritis for 12.19 (±11.2) years. Men accounted for only 18.2%. Osteoarthritis affected three joints on average. Nearly 61% of participants were not married, but most (> 85%) were educated at the high school or college level. Over 70% were unemployed due to disability or retirement, and a large proportion (64.5%) had just enough income to pay bills and buy necessities.

4.2. Stage of engagement in core recommended treatments

Although motivation for self-management was high (M = 8.30 ± 2.3), their narratives illuminated unique cultural insight into how participants felt about their own motivation level as well as the motivation level of other Black Americans with osteoarthritis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Motivation to manage pain (N = 110).

| On a scale of 0–10, how motivated are you to effectively manage your pain? | |

| Sample average (SD) | 8.30 (2.3) |

| Frequency by motivation level N (%)a | Motivation exemplar |

| No motivation = 0 N = 2 (1.8) |

Perspective of self: “You gotta get motivated. Well, got to get more confident than I am right now, but sitting here talking to you [researcher], you motivate me to get out there and go to walking.” |

| Perspective of the black community: (1) “It’s hard to get ‘em motivated when they don’t want to. They [Black Americans] need support for one thing. They ain’t gonna do it on their own. They need support from each other.”; (2) “Well, the ones that ain’t gon wanna do that ain’t gon’ do it no way.” | |

| Low motivation = 1–3 N = 2 (1.8) |

Perspective of self: “I see a lot more proactive counselling with diabetes, than I do with arthritis. That’s why I sayin’, when they get it, they need to be just as proactive as they are when you get diabetes.” |

| Perspective of the black community: (1) “It’s gotta be some kind of motivation through knowledge, some kind of way you can dispense knowledge to them that can get them to thinking about the importance of it.”; (2) “Cuz if you are uninformed, I mean, that’s just like bein’ unequipped for whatever, a job, or a whatever. I mean, now that’s bad, but some people are, I do know.” | |

| Moderate motivation = 4–6 N = 17 (15.5) |

Perspective of self: “I think my main thing I need is to be motivated, and I love reading. Like I said, I just try to keep a positive attitude about life and your health, and don’t think, just because you’ve got some issues that you gotta sit down. You can work on it and make it better. I’m gonna go in there and start exercising as soon as you leave.” |

| Perspective of the black community: Motivation, that’s a big question. Well, I think probably, like we’ve done, and I am grateful, and I know that every area don’t have that, is that we have a social worker. And so I think it’s not a easy task, but I think it’s something that has to be done, on a continuing basis, and probably won’t win everybody, but we will win some. Managing the pain—the help that’s out there for it.” | |

| High motivation = 5–7 N = 8 (7.3) |

Perspective of self: “Taking care of health motivates me to walk.” |

| Perspective of the black community: “Let ‘em know it can get better. We can find out what we need to use on our body, cream or whatever it is, what’s helpful to us.” | |

| Very high motivation = 8–10 N = 80 (99.1) |

Perspective of self: “To me, I think a lot of it’s got to be self. If you want it. If you wanna manage that pain, it’s got to be up here. I can do this. I’m gonna manage this. It’s about like exercise. It’s ‘bout like losin’ weight. All basically the same thing. You gotta encourage. Plus, I feel like if you had other people in the same situation that help to give you that support, too.” |

| Perspective of the black community: No narrative available. | |

0 = being not motivated to 10 = being highly motivated.

Missing N = 1.

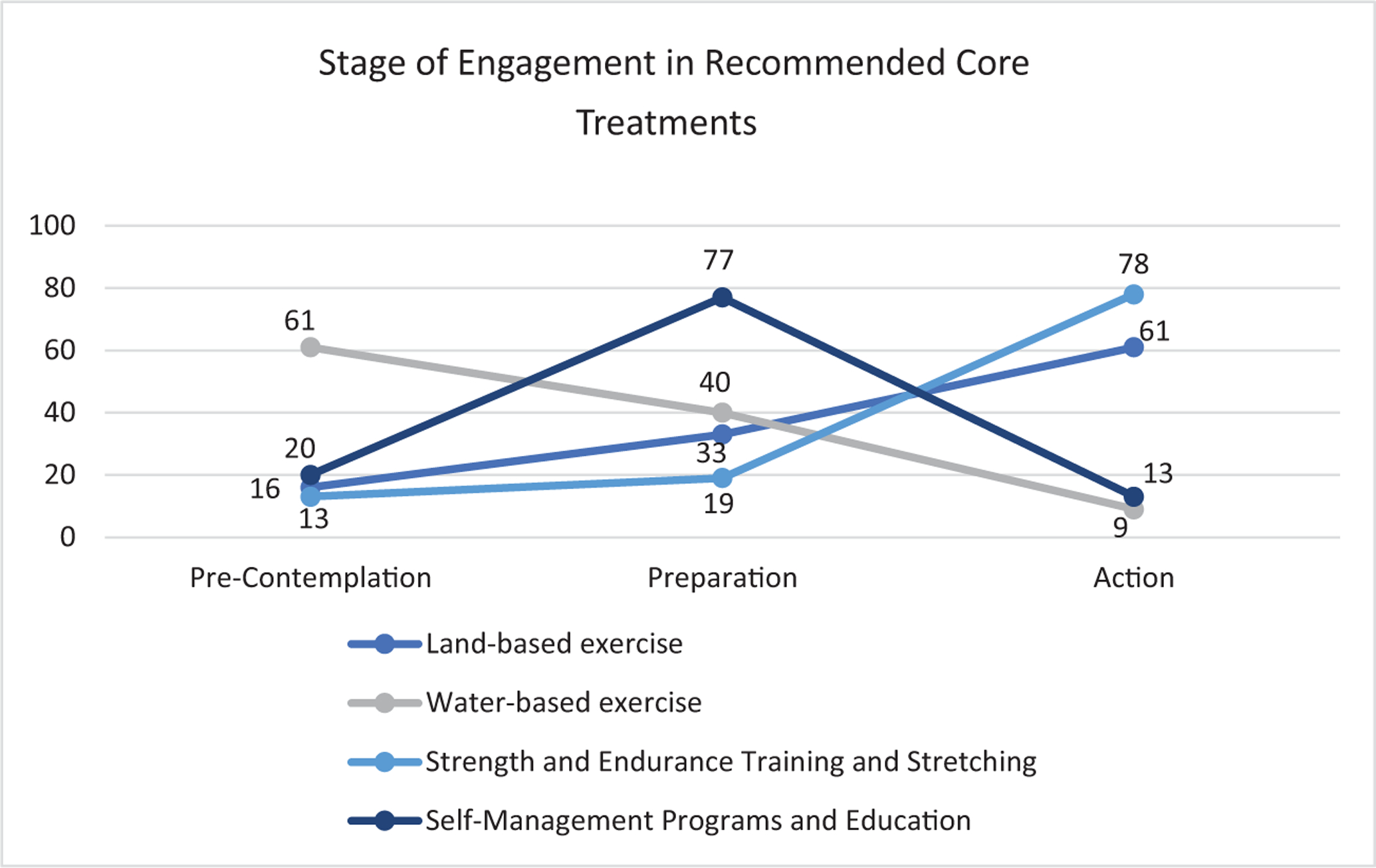

Study participants were engaged at varying levels in recommended treatment options: land-based exercise, water-based exercise, strength training, self-management program and education (Fig. 1). According to the PSMEQ, 55.5% (n = 61) of older Black Americans were actively involved in some type of land-based exercise, primarily walking, but were not engaged in water-based exercise (n = 9, 8.2%). Strength training was frequently included with exercise, and 70.9% (n = 78) did report using strengthening exercises explicitly. Self-management and education had the second lowest engagement rate at 11.8% (n = 13), but the highest preparation rate as many participants reported wanting to participate in self-management and education programs.

Fig. 1.

Stage of engagement in recommended core treatments (N = 110).

4.3. Barriers and motivators for core recommended treatments

Each recommended behavior had a distinctive set of barriers and motivators. Because only the most salient barriers and motivators are presented, frequencies may not equal the response rate. We present exemplar quotes for each treatment in Table 2.

4.3.1. Land-based exercise

Of the 69 (62.7%) providing a response, nearly half (n = 29, 26.4%) reported barriers to engagement in land-based exercise, these being both physical and cognitive barriers. The lead barriers included pain (n = 10), lack of time attributed to work schedule and family responsibilities (n = 6), lack of motivation (n = 6), physical environmental safety (n = 3), and mobility limitations (n = 3). An unsafe physical environment (e.g., uneven surfaces such as pavement and fear of dogs in the neighborhood), combined with existing mobility issues, limited participation in land-based exercise.

“The only thing you can do is go through therapy and stuff like that. Keep your joints mobilized. Cause I went to the rehabilitation department. She [physical therapist] did a little exercise with me and then give me a piece of paper talking about do these every day. If I could do that I wouldn’t need to be there with you. I need somebody to help with these joints and muscles.”

Pain was both a barrier and motivator. Experiencing pain or inducing pain from exercise prevented engagement, while the pain itself motivated participants to do something. One participant who wanted to exercise commented, “ain’t no sense in getting up to hurt.” When pain was an issue, one older woman adapted her exercise by doing chair exercises. The third barrier was lack of motivation to get involved.

“They tell everybody exercise. Yeah, I know that, but I just couldn’t get motivated. One day, one night, I was like, “I just feel like dancing or somethin’.” I went to one of them line-dancing that you can do. …I’ ll do exercise.”

The most influential motivators were opposite conditions of the barriers. For example, the two most common motivators were finding exercise helpful for pain relief (n = 9) and to maintain mobility and good health (n = 8). Other important facilitators included working out with a group (n = 4), having exercise equipment (n = 2), and to help with other chronic conditions (n = 2; e.g., hypertension and diabetes). When participants exercised in group settings, such as the senior center, church and during physical/occupational therapy, this behavior was viewed more positively. “Aerobics is fun and stimulating, in that it is a group activity” as stated by one person.

4.3.2. Water-based exercise

Water-based exercise received the second highest response rate (n = 61, 55.5%) for barriers and motivators. Aquatic exercise was associated with major barriers in older Black Americans, the two greatest barriers being lack of access to a pool (n =22) and inability to swim/dislike of water (n = 18). The inability to swim was translated as a fear of drowning, in which one participant commented that she was afraid of water and that she does not even fill her bathtub too full. There were a few who reported a willingness to learn how to swim because they heard it was helpful. In many of the communities, there was no pool in the area. Some had to drive 30 minutes away if they wanted to attend a water aerobics class. One participant noted that insurance would not pay for a water-aerobics class.

Several participants reported past participation and enjoyed aquatic exercise, but personal and environmental safety (n = 7), lack of motivation and time (n = 7 and n = 4, respectively), and health problems (n =5) prevented engagement. Participants were concerned about their mobility, fall risk, and not being able to get in and out of pool safely. While there were those who simply were not interested or motivated in water-based exercise as a pain-relief strategy, only two participants mentioned pain as a barrier. Interesting enough, there were five participants who said nothing prevented them from engaging in water-based exercise. The remaining barriers cited include lack of information, needing an exercise partner, and personal beliefs. One personal belief that symbolizes a generational and cultural view detering water-exercise is “I don’t want to get a cold” which was shared by an 83-year-old woman. Despite the barriers, several discussed purchasing a walk-in tub with jets, swim spa, or pool.

Given the preponderance of barriers, there were significantly fewer motivators. Having access to a pool (n = 6) and finding water exercise enjoyable (n = 3) were the main motivators. Having a provider recommendation prompted two people to try water- based exercise. Only a few older Black Americans recounted water- exercise as helpful with pain and joint mobility, with one saying, “It’s very beneficial because I really can move without hurting myself as opposed to doing land aerobics.” Another participant made a similar statement, but pointed out the effect of pain, “did before and it helped in the water but as soon as I got out of car, started to feel the pain.” It appears the barriers significantly outweigh the benefits to potential users.

4.3.3. Strength training

This behavior had the lowest response rate with only 35 (38.1%) reporting either a barrier or motivator. Several conveyed that there were no barriers (n = 4). Barriers consisted of not devoting time (n = 3), pain (n = 3), no motivation (n = 2)and health problems (n = 1). On the other hand, there were more motivators described which included relief of pain (n = 9), to strengthen joints and improve flexibility for safe mobility (n =7), exercising either as a group or individually (n = 6), having exercise equipment (n =3), and for relaxation (n = 3). By strengthening joints, participants believed their stiffness was reduced and balance was improved: “It strengthens my bones and the surrounding muscles and keeps my joints strong, avoiding falls and mishaps with walking.” Of course, having exercise equipment at home, such as simple stretch bands or using soup cans as weights, was a motivator. Lastly, some found strength training and stretching as relaxing and as a preparatory step to exercise.

4.3.4. Self-Management programs and education

Only 7 (6.4%) Black Americans initiated self-directed self-management education and even fewer reported attending a self-management program (n = 2). When asked more directly if they had ever participated in an educational program or workshop on osteoarthritis self-management or chronic pain self-management, this elicited a slightly higher response with 13 (11.8%) responding yes. Open-ended responses on the importance of self-management education revealed that older Black Americans believed that such programs could teach them pain management and coping skills and felt strongly that culturally-customizing self-management education was important.

Response rates (n = 61, 55.5%) and barriers for participation in a chronic pain or arthritis self-management program mirrored similarities to water-based exercise. A lack of access to a self-management program was the predominant barrier (n = 8). This access was either physical or cognitive, meaning that a program was not available in the area or that participants were not knowledgeable of any programs or of this as a recommendation for osteoarthritis. Additional barriers related to lack of time (n = 6), information (n = 6), transportation (n = 5), and motivation (n =2), health problems (n = 3), the belief that such a program would not be helpful (n = 4), and cost (n = 1). In fact, one older gentleman acknowledged that he didn’t understand how a self-management class could be helpful because he “didn’t have much time left” (years to live); he believed that since he’s lived this long with osteoarthritis pain that there was no need to try and learn. It is this kind of passive behavior for self-management that results in low motivation. Another commented that the program facilitators/instructors “probably can’t teach me nothing… I would teach them.”

In contrast, the top motivator included a desire to learn pain management skills (n = 12). Example skills included learning about pain, medications, types of exercises, best strategies for pain relief, natural remedies, and coping skills (or how to control the mind). Having participated in health-related classes and programs in the past was also motivating factor (n = 5): “It [self-management program] gives the tools that promotes a healthier life. Learn things for pain modification as well as things to help emotionally”. One woman noted an interesting feature of a program she had taken, which was the ability to take various devices home and trial them to see if they help with pain. To further motivate participation, the program would need to be inexpensive and accessible (i.e., have transportation or be located in the community or home-based).

4.4. The experience of pain self-management motivation

As demonstrated above, various factors influence older Black Americans’ motivation and ability to utilize recommended osteoarthritis treatments. Motivation to actively participate in self-management often includes actions to reduce and limit the progression of osteoarthritis pain and its impact on physical function. Analysis illuminated two themes: doing nothing and Increasing motivation

4.4.1. Doing nothing

It was interesting and disheartening to hear that “…as American Black folks, they just really say they don’t give a damn because there ain’t nothing they can do”. While all reported at least one self-management strategy, there was minimal intention in using recommended treatments to slow the advancement of osteoarthritis, either because they didn’t know what to do or were not motivated. Participants were reflective and asked themselves, “How did I get here?” You know what I mean? Those thoughts run through my mind. “How did I get here?”… How did I allow myself to get to this point?” Their hindsight revealed a need to be more physically active through exercise, better eating habits, and greater self-education; “Just like I heard this man say, ‘If I knew I was gonna live as long as I have lived, I’d of took better care of myself than what I did.’ [Laughter]”. Consider one man’s perspective

“Anything you can do bout that—you can’t do nothin’ about that. See, if a person is not going to look out for their own arse [ass] when they in pain, ain’t nothin’ you can do about that. You just might as well just step back and say, “Hey, did you do what you know you supposed to do?” “No.” “Guess what, this should be a bulletin for you.” Okay, and you ain’t no different than nobody else. Okay? It’s your arse. [Laughter] Now, you ain’t gonna do nothin’ about it, it’s on you. It ain’t on nobody else.”

An older woman articulated,

“I think, number one, I think it’s the knowledge, no motivation, and number three, just really disbelief. … Disbelief in that, since the father had it, the cousin had it, and everybody in the family had it, now it’s my turn. And you’re right, because I do see people who seem like this is a banner that they’re waving. I got this, or I finally got it. …There’s nothing I can do about it. That’s the worst kinda thought. I just do believe that a person could have, because technology and medicine and everything is so changed. …I think, for us, it’s hard getting out of our comfort zone, because other people say it’s not gonna bother you.”

In retrospect, participants realized they should have been or should be more proactive and active in managing their osteoarthritis pain. Such reflection was a mechanism for increasing motivation.

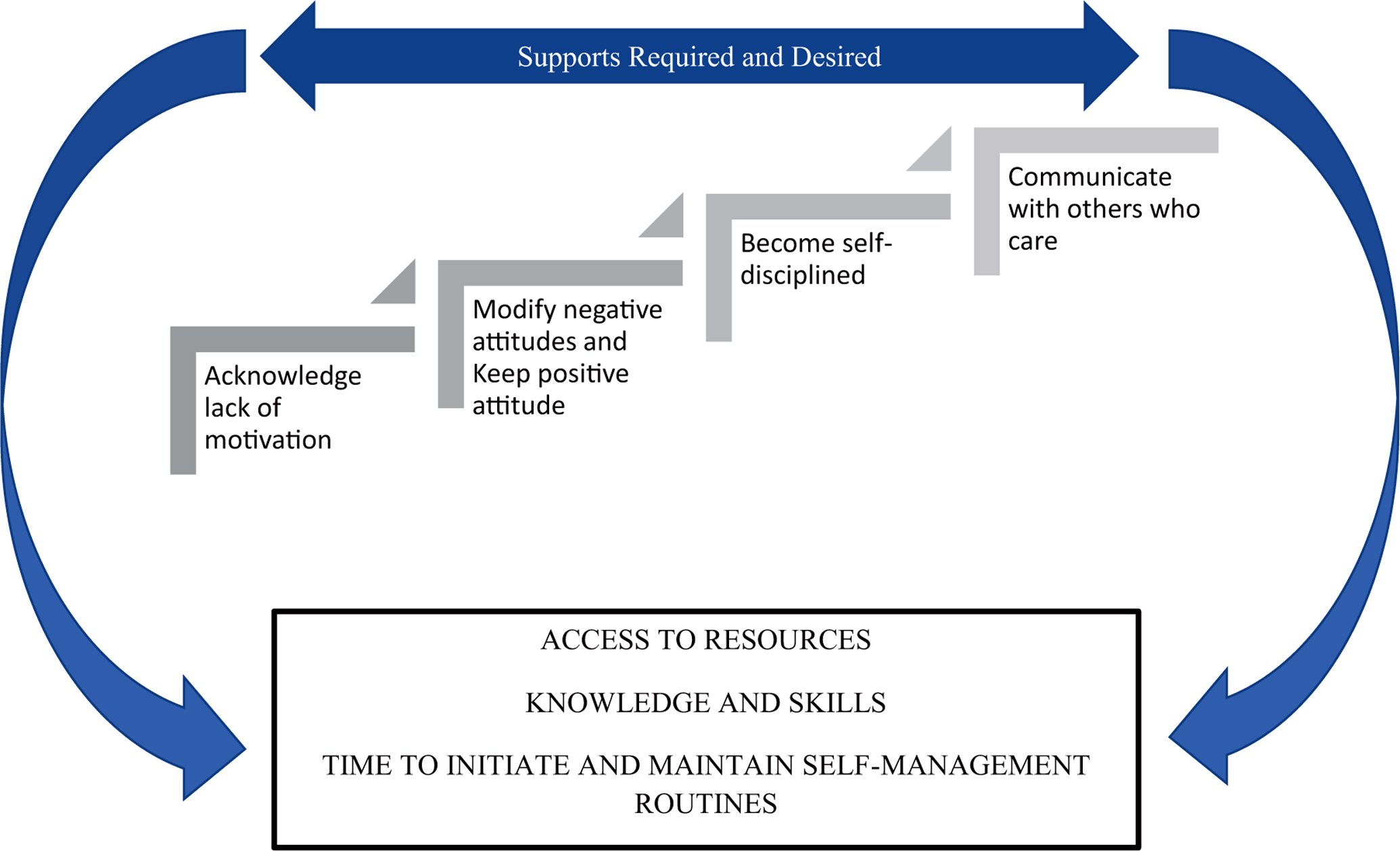

4.4.2. Increasing motivation

Motivation for self-management was hindered by doing nothing, but interestingly, Black Americans revealed the key ingredients for increasing motivation, and this resulted in a ‘lay formula’ (Fig. 2). Eighteen participants were asked, “What could we do to motivate our people [Blacks/African Americans] to better manage their pain?” This was a complex and convoluted question for many, and participants spoke of four distinct, almost systematic, steps to do this: acknowledge their lack of motivation (N = 5), modify negative attitudes and keep a positive attitude (N = 8), become disciplined (N = 5), and talk to someone who cares (N = 5).

Fig. 2.

Four steps to increasing personal motivation for pain self-management.

Acknowledge lack of motivation.

First, older adults noted a need to acknowledge their lack of motivation and recognize the role of self-motivation. As one lady puts it, “It’s got to be self. To me, I think a lot of it’s got to be self. If you wanna manage that pain, it’s got to be up here [mind]. I can do this. I’m gonna manage this.”

Modify negative attitudes.

Mitigating these laissez fare beliefs and negative conceptions about pain management was the third major motivational process. “What I realized, I should have been watching what I eat. I should have been exercising more. I should have been reading and educating myself on things I need to do. Then, I finally said, ‘That’s behind me now.’ …That’s when I started concentrating on… Now I wanna do more. Do something better…because I don’t wanna ever get that way again.” Transitioning from a pity perspective to a power perspective was indicated by Black Americans’ need to change their outlook.

“Like I said, I just try to keep a positive attitude about life and your health, and don’t think, just because you’ve got some issues that you gotta sit down. You can work on it and make it better. …E- specially in my older years, I think about still just making lifestyle changes. Just because I’m old, that don’t mean I can’t change the way I do certain things.”

Become disciplined.

Becoming self-motivated and engaging in health behavior change was not easy and required some to be sporadic in changing their physical activity patterns:

Interviewer: Yeah. It does take a lot of discipline though

Interviewee: Yeah, but that’s the hardest part

Interviewer: Yeah, it is

Interviewee: When I had that surgery, when the guy was talking to me about my knees, I said, “I don’t have a problem losing weight. The problem I have is I always gain it back. ”

It was similar acts of becoming disciplined, whether with exercise or taking medications, that older Black Americans lacked.

Talk to someone who cares.

Older Black Americans appreciated talking to someone who cares about their condition and experiences. On multiple occasions they mentioned that talking to the researcher actually motivated them. It was likely the act of having someone listen to their issues and make simple, unpretentious recommendations that facilitated their view. This revealed a need for greater social support in managing any chronic condition including osteoarthritis pain (Booker et al., 2019). Characteristics, such as caring, empathetic, and genuineness, are key qualities that older Black Americans look for in researchers and providers. Overall, increasing motivation was a multifaceted issue involving improved access to treatment and education, recognizing and reducing ineffective behaviors, modifying negative or inaccurate health beliefs/attitude, and having social support.

5. Discussion

This is a novel study that explored how older Black Americans’ motivation for self-management aligned with recommended osteoarthritis treatments. The blended quantitative and qualitative findings expand our knowledge on engagement patterns in osteoarthritis self-management, as well as the personal, social, and system factors that help explain engagement in core recommended treatments. This is an essential step to resolving disparities in pain care, but also in tailoring care to meet the individual needs of patients. What was clear from Black participants was their need to “get motivated.” The Expectancy Theory of Motivation proposes that an individual voluntarily chooses to enact a specific behavior because they are motivated by the expected result, typically a desirable outcome (Vroom, 1964). Our findings suggested that motivation is not only driven by the result for pain relief but by the resources available. Because symptoms of osteoarthritis can be dynamic, individuals’ motivation and ability to engage in self-management may fluctuate and individuals may move back and forth between stages of engagement and progress through the stages at varying rates.

5.1. Overcoming barriers and getting motivated

Although Black Americans rated a high motivation to manage pain, further qualitative probing revealed that lack of motivation was a major deterrent in their ability and willingness to be more involved in their personal self-management. In addition, a balance is needed between prescribing what is recommended and what is available and preferred to older Black Americans, and this is where elucidating the barriers and motivators provided critical information. As discussed, a specific set of barriers and facilitators emerged for each recommended behavior. Not surprisingly, however, either having pain or seeking pain relief was both a leading barrier and motivator to engagement in most of the recommended behaviors. It is clear that participants responded to behaviors in which they felt more confident and that more active individuals reported fewer barriers and more facilitators as compared to those less active. Of course, participants also used treatments that they were aware of, given that it is impossible to use a treatment if a person has inadequate exposure to and access or support for use.

Inability to afford fitness/health club memberships and living in unsafe neighborhoods are additional unique socioeconomic disparities that limit Black Americans participation in exercise and community-based self-management programs (Ard et al., 2005; Mingo et al., 2013). Depression and lack of motivation are additional barriers to participation in physical activity and exercise for chronic pain self-management in ethnically diverse older adults (Park, Hirz, et al., 2013). While depression was not cited in our study, lack of motivation or no interest were reported. Consistent with literature, similar barriers to physical activity and exercise were noted for Black American and Caucasian older adults and were identified as pain, falls, injuries, and health issues (Kosma and Cardinal, 2016). Participants from our study and the Kosma et al. study resided in southern states, which lends greater credibility and generalizability of our results to other older Black Americans in the southern US.

A study by Fisken et al. (2016) revealed that pain relief was perceived as a benefit and motivator for use of aquatic exercise by New Zealander older adults. Even though some in our study acknowledged the benefit of aquatic exercise in relieving pain, the lack of access and inability to swim were overwhelming constraints. Consistent with our findings, fewer Black participants had participated in aquatic exercise when compared to Caucasians (Park et al., 2014). Perhaps if older Black Americans had access and resources to overcome the fear and misconception that ability to swim is a pre-requisite for water-based exercise, they would be better equipped to understand the benefit and feasibility of this type of therapy.

In our sample less than 1% engaged in a pain self-management program or self-directed education, comparable to Silverman’s et al. findings of less than 2% engagement (2008). Despite this, our data reveal that a large majority are interested in attending such a program at some point. Others may not even understand the benefits of participating in a chronic pain self-management program (Townley et al., 2010), and could underlie Black Americans are significantly less likely than Caucasians to believe that a self-management program will be helpful (Mingo et al., 2013). These beliefs when combined with contextual barriers may help explain a lower motivation to participate in a self-management program. Furthermore, failing to tailor programs to Black Americans’ needs and culture can adversely impact interest, participation, and outcomes (McIlvane et al., 2008). Unlike the other three core treatments, self-management programs and education are not recommended on a daily or weekly basis, which could also affect utilization rates and unique qualitative differences. However, when self-management programs are attended by ethnically diverse elders, completion rate is high and ranges from 61% to 91% (Parker et al., 2011; Reid et al., 2014; Sperber et al., 2013).

Looking to future research, it has been proposed that locus of pain control should be further explored in relation to motivation to self-manage pain (Hadjistavropoulos and Shymkiw, 2007). Meanwhile, using the four steps to increase motivation as identified by our participants may serve as a more culturally-realistic framework for theory-guided and evidence-informed intervention design and delivery, but it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss theory development and use. Future research also lends itself to better characterizing motivation factors as intrinsic versus extrinsic within a more sociocultural context.

5.2. Implications for nursing nationally and internationally

The Relieving Pain in America report (commissioned by the Affordable Care Act’s National Pain Care Policy Act of 2010) and national organizations have emphasized the importance of research and improving quality and equity in osteoarthritis and pain care through access to evidence-based arthritis interventions and promotion of self-management in diverse populations (IOM 2011 ; Lubar et al., 2010). This can be accomplished by “optimize[ing] the use of and access to currently available treatments that are known to be effective” (Gereau et al., 2014, p. 1205). From a stage-theory perspective, interventions to facilitate change will be most effective if they are tailored to the stage an individual has reached within this process (Eccles et al., 2012). Thus, our findings offer a timely opportunity to focus community-based efforts to expand arthritis education outreach to build older Black Americans self-management capacity, understand their experiences and their needs, and design and test the effectiveness of complementary and alternative strategies in all older adults, but especially ethnic minority older adults. Henceforth, the extent to which ensuring Black American older adults’ preferences for education are incorporated into self-management interventions coupled with contextualizing the realistic nuances of care that disadvantaged populations face daily will be critical to the success of symptom science.

While this study focused on a specific U.S. sub-population, it is likely that other rapidly aging countries with ethnic minority older adults experience similar but also unique barriers and motivators to chronic pain self-management. Our findings can be transferred to international audiences and adapted to the sociodemographic context of an area. The role of nurses globally focuses on education, advocacy, and self-management support. Expanding the diversity of research participants and their documented experience of pain is a key to reducing disparities and inequities worldwide and to advancing the clinical and political agendas that support self-management.

5.3. Strengths and limitations

We report notable strengths, primarily the collection of data using multiple methods and perspectives to offset potential recall and response biases. The findings from our study support those of previous studies exploring the barriers and motivators to arthritis and chronic pain self-management, but the use of theory enhanced our study design and understanding and interpretation of the data. Also, data are from community-dwelling adults rather than hospital or clinic patients, which increases diversity of representation in terms of health status and the realities of everyday people with osteoarthritis.

Because of the non-experimental study design, there are several limitations including sampling approach (convenience sample from a localized geographic region) and data collection (self-report measures). Self-selection bias, where highly interested and motivated participants were more likely to participate in this research, must be considered; as a result, “in stages of change terminology, pre-contemplators are under-sampled” (Lee et al., 1997, p. 378). Findings are limited to non-institutionalized older Black Americans residing in a discrete geographic location (north- central/northwestern Louisiana). Participants were from either a rural or urban area, and stage of engagement was not significantly different between geographic settings which strengthens external validity. Lastly, a few of the optional open-ended survey questions had low response rates, but we were nonetheless able to explicate some important barriers and motivators from the responses provided.

6. Conclusion

Reducing the effect of chronic pain is a high priority throughout the U.S. Though self-management is promoted as the primary method of managing osteoarthritis, we discovered that engagement in core osteoarthritis treatment options is inconsistent with what is recommended, predominantly due to barriers that are difficult to overcome. In these cases, motivation alone is not optimal in promoting self-management. Rather, researchers and providers are urged to work to eliminate barriers and maximize motivators according to a motivational process congruent with Black Americans’ views and culture. Additional research is needed to disentangle the complex construct of motivation, particularly its structure and dynamics in influencing self-management.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about the topic?

Self-management is essential for effective and long-term management of osteoarthritis.

Core treatments recommended for the management of osteoarthritis are land-based exercise, water-based/aquatic exercise, strength training, and self-management programs and education.

Older Black Americans are more likely to engage in self-management behaviors that are tried and true, inexpensive, culturally-recognizable, and easy to use.

What this paper adds

Black American older adults reported a high motivation to manage pain on surveys, but qualitative data also discovered a significant lack of motivation and subsequent action.

Over 55% of older Black Americans were actively engaged in land-based exercise and strength training but significantly fewer in water-based exercise or self-management programs and education.

A range of barriers and motivators were discovered in relation to each recommended treatment, including lack of motivation and pain itself.

Motivation alone is not optimal in promoting self-management without the resources, skills, and social support.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research [T32NR011147-06A1].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary materials Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103510.

References

- Allen KD, Arbeeva L, Cené CW, Coffman CJ, Grimm KF, Haley E, Keefe FJ, Nagle CT, Oddone EZ, Somers TJ, Watkins Y, Campbell LC, 2018. Pain coping skills training for african americans with osteoarthritis study: baseline participant characteristics and comparison to prior studies. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord 19 (1), 337. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert SM, Musa D, Kwoh CK, Hanlon JT, Silverman M, 2008. Self-care and professionally guided care in osteoarthritis: racial differences in a population-based sample. J. Aging Health 20 (2), 198–216. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ard JD, Durant RW, Edwards LC, Svetkey LP, 2005. Perceptions of african-american culture and implications for clinical trial design. Ethn. Dis 15, 292–299. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austrian JS, Kerns RD, Reid MC, 2005. Perceived barriers to trying self-management approaches for chronic pain in older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 53 (5), 856–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, Yazdanshenas H, Gordon D, Orum G, 2016. Pain in community- dwelling elderly black americans. J. Aging Health 28 (3), 403–425. doi: 10.1177/0898264315592600 . 10.1177/0898264315592600https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315592600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315592600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill-Harvey D, Rippey RM, Abeles M, Pfeiffer CA, 1989. Methods used by urban, low-income minorities to care for their arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2 (2), 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH, Hoy DG, March LM, 2019. The global burden of musculoskeletal pain—Where to from here? Am. J. Public Health 109 (1), 35–40. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ, Cousin L, Buck HG, et al. , 2019. “Puttin’ On”: Expectations Versus Family Responses, the Lived Experience of Older African Americans With Chronic Pain. J. Fam. Nurs 25 (4), 533–556. doi: 10.1177/1074840719884560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker S, Herr K, Tripp-Reimer T, 2018. Patterns and Perceptions of Self-Management for Osteoarthritis Pain in African American Older Adults. Pain Med December 12 [Online ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V, 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol 3, 77–101. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0008 [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Gravely AA, Nelson DB, van Ryn M, Bair MJ, Kerns RD, Higgins DM, Partin MR, 2013. A national study of racial differences in pain screening rates in the va health care system. Clin. J. Pain 29 (2), 118–123. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31826a86ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed. SAGE Publishing, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0010 [Google Scholar]

- Dattalo M, Giovanetti ER, Scharfstein D, Boult C, Wegener S, Wolff JL, Boyd C, 2012. Who participates in chronic disease self-management (CDSM) programs? differences between participants and nonparticipants in a population of multimorbid older adults. Med. Care 50 (12), 1071–1075. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobscha SK, Soleck GD, Dickinson KC, et al. , 2009. Associations between race and ethnicity and treatment for chronic pain in the VA. J. Pain 10 (10), 1078–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, MacLennan G, Bonetti D, Glidewell L, Pitts NB, Johnston M, 2012. Explaining clinical behaviors using multiple theoretical models. Implement. Sci 7, 99. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiargo MK, Williams-Russo P, Allegrante JP, 2005. Expectation and outlook: the impact of patient preference on arthritis care among african americans. J. Am- bulat. Care Manag 28 (1), 41–48. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibel KH, Hillstrom HJ, Halpern BC, 2015. State-of-the-Art management of knee osteoarthritis. World J. Clin. Cases 3 (2), 89–101. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisken A, Keogh JWL, Waters DL, Hing WA, 2016. Perceived benefits, motives, and barriers to aqua-based exercise among older adults with and without osteoarthritis. J. Appl. Gerontol 34 (3), 377–396. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers PPE, Schwartz TA, Arbeeva L, Golightly YM, Pathak A, Cooke J, Gupta JJ, Callahan LF, Goode AP, Corsi M, Huffman KM, Allen KD, 2019. Racial differences in performance-based function and potential explanatory factors among individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis. Care Res. (Hoboken) doi: 10.1002/acr.24018, Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2017. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 390, 1211–1259. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereau RW 4th, Sluka KA, Maixner W, Savage SR, Price TJ, Murinson BB, Sullivan MD, Fillingim RB, 2014. A pain research agenda for the 21st century. J. Pain 15 (12), 1203–1214. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golightly YM, Allen KD, Stechuchak KM, Coffman CJ, Keefe FJ, 2015. Associations of coping behaviors with diary based pain variables among caucasian and black american patients with osteoarthritis. Int. J. Behav. Med 22 (1), 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Schulman-Green, Knafl K, Reynolds NR, 2015. A revised self- and family management framework. Nurs. Outlook 63 (2), 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubert E, Baker TA, McGreever K, Shaw BA, 2013. The role of pain in understanding racial/ethnic differences in the frequency of physical activity among older adults. J. Aging Health 25 (3), 405–421. doi: 10.1177/0898264312469404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H, Shymkiw J, 2007. Predicting readiness to self-manage pain. Clin. J. Pain 23 (3), 259–266. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, Toupin April K, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, Towheed T, Welch V, Wells G, Tugwell P, et al. American College of Rheumatology, 2012. American College of Rheumatology 2012 Recommendations for the Use of Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Therapies in Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 64 (4), 465–474. doi: 10.1002/acr.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE, 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res 15 (9), 1277–1288. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK, 2001. Variation in perceptions of treatments and self-care practices in elderly with osteoarthritis: a comparison between black american and white patients. Arthrit. Rheum 45 (4), 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, 2011. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0026 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Nielson WR, Kerns RD, 2003. Toward the development of a motivational model of pain self-management. J. Pain 4 (9), 477–492. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Nielson WR, Turner JA, Romano JM, Hill ML, 2004. Changes in readiness to self-manage pain are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment and pain coping. Pain 111 (1–2), 84–95. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AC, Kwoh CK, Groeneveld PW, Mor M, Geng M, Ibrahim SA, 2008. Investigating racial differences in coping with chronic osteoarthritis pain. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol 23, 339–347. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawi J, 2013. Self-management and support in chronic pain subgroups: integrative review. J. Nurse Practit 9 (2), 110–115. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0030 [Google Scholar]

- Keogh A, Tully MA, Matthews J, Hurley DA, 2015. A review of behavior change theories and techniques used in group based self-management programmes for chronic low back pain and arthritis. Man. Ther 20 (6), 727–735. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosma M, Cardinal BJ, 2016. Theory-based physical activity beliefs by race and activity levels among older adults. Ethn. Health 21 (2), 181–195. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RE, McGinnis KA, Sallis JF, Castro CM, Chen AH, Hickman SA, 1997. Active vs. passive methods of recruiting ethnic minority women to a health promotion program. Ann. Behav. Med 19 (4), 378–384. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG, 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry SAGE Publishing, Inc, Beverly Hills, CA. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0035 [Google Scholar]

- Lubar D, White PH, Callahan LF, Chang RW, Helmick CG, Lappin DR, Waterman MB, 2010. A national public health agenda for osteoarthritis 2010. Semin. Arthritis Rheum 39 (5), 323–326. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KR, Schoster B, Woodard J, Callahan LF, 2012. What community resources do older community-dwelling adults use to manage their osteoarthritis? a formative examination. J. Appl. Gerontol 31 (5), 661–684. doi: 10.1177/0733464810397613 . 10.1177/0733464810397613https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464810397613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464810397613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. , 2014. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarth. Cartil 22, 363–388. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlvane JM, Baker TA, Mingo CA, Haley WE, 2008b. Are behavioral interventions for arthritis effective with minorities? addressing racial and ethnic diversity in disability and rehabilitation. Arth. Rheum 59 (10), 1512–1518. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingo CA, McIlvane JM, Jefferson M, Edwards LJ, Haley WE, 2013. Preferences for arthritis interventions: identifying similarities and differences among black americans and whites with osteoarthritis. Arth. Care Res 65 (2), 203–211. doi: 10.1002/acr.21781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler JN, Martsolf GR, Telenko SJ, Scanlon DP, 2013. Making sense of “consumer engagement” initiatives to improve health and health care: a conceptual framework to guide policy and practice. Milbank Q 91 (1), 37–77. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AM, 2001. Self-help care in older african americans with arthritis. Geriatr. Nurs 22 (3), 135–138. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Johnson RB, 2006. The validity issue in mixed research. Res Schools 13 (1), 48–63. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0043 [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Hirz CE, Manotas K, Hooyman N, 2013. Nonpharmacological pain management by ethnically diverse older adults with chronic pain: barriers and facilitators. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 56, 487–508. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2013.808725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lavin R, Couturier B, 2014. Choice of nonpharmacological pain therapies by ethnically diverse older adults. Pain Manag 4 (6), 389–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SJ, Chen EK, Pillemer K, Filiberto D, Laureano E, Schwartz-Leeper J, Robbins L, Reid MC, et al. , 2012. Participatory Adaptation of an Evidence- Based, Arthritis Self-Management Program: Making Changes to Improve Program Fit. Fam. Community Health 35 (3), 236–245. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318250bd5f . 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318250bd5fhttps://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0b013e318250bd5f. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0b013e318250bd5f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SJ, Vasquez R, Chen EK, et al. , 2011. A comparison of the arthritis foundation self-help program across three race/ethnicity groups. Ethn. Dis 21, 444–450. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0047 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peat G, Thomas E, 2009. When knee pain becomes severe: a nested case-control analysis in community-dwelling older adults. J. Pain 10 (8), 798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, 1997. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot 12 (1), 38–48. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MC, Chen EK, Parker SJ, Henderson CR Jr., Pillemer K, 2014. Measuring the value of program adaptation: a comparative effectiveness study of the standard and a culturally adapted version of the arthritis self-help program. HSS J. Musculosk. J. Hosp. Spec. Surg 10 (1), 59–67. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MC, Papaleontiou M, Ong A, Breckman R, Wethington E, Pillemer K, 2008. Self-management behaviors to reduce pain and improve function among older adults in community settings: a review of the evidence. Pain Med 9 (4), 409–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Jaarsma T, Lee CS, Strömberg A, 2019. Integrating symptoms into the middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci 42 (3), 206–215. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, 2009. Integrated theory of health behavior change: background and intervention development. Clin. Nurse Spec 23 (3), 161–172. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181a42373 . 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181a42373https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181a42373. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181a42373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, Sawin KJ, 2009. The individual and family self-management theory: background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs. Outlook 57 (4), 217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shively MJ, Gardetto NJ, Kodiath MF, Kelly A, Smith TL, Stepnowsky C, Larson CB, 2013. Effect of patient activation on self-management in patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 28 (1), 20–34. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman M, Nutini J, Musa D, King J, Albert S, 2008. Daily temporal self-care responses to osteoarthritis symptoms by older black americans and whites. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol 23, 319–337. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Hochberg MC, Chang RW, Hootman JM, Manheim LM, Lee J, Dunlop DD Osteoarthritis Initiative Investigators, 2013. Racial and ethnic differences in physical activity guidelines attainment among people at high risk of or having knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 65 (2), 195–202. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber NR, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, Lindquist JH, Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, Allen KD, 2013. Differences in osteoarthritis self-management support intervention outcomes according to race and health literacy. Health Educ. Res 28 (3), 502–511. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C, Schofield P, Elliot AM, Torrance N, Leveille S, 2014. What do we mean by “older adults’ persistent pain self-management”?: a concept analysis. Pain Med 15, 214–224. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townley S, Papaleontiou M, Amanfo L, Henderson C, Pillemer K, Beissner K, Reid MC, 2010. Preparing to implement a self-management program for back pain in new york city senior centers: what do prospective consumers think? Pain Med 11, 405–415. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand AH, 2018. Pain-related disparities: are they something nurses should care about? Pain Manage. Nurs 9 (1), 1–2. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn IA, Terry EL, Bartley EJ, Schaefer N, Fillingim RB, 2019. Racial-ethnic differences in osteoarthritis pain and disability: a meta-analysis. J. Pain 20 (6), 629–644. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0020-7489(19)30317-7/sbref0062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vina ER, Ran D, Ashbeck EL, Kwoh CK, 2018. Natural history of pain and disability among african-americans and whites with or at risk for knee osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. Osteoarthr. Cartil 26 (4), 471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.01.020 . 10.1016/j.joca.2018.01.020https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.01.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vroom VH, 1964. Work and Motivation Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.