SUMMARY

Maternally inherited RNA and protein control much of embryonic development. The impact of such maternal information beyond embryonic development is largely unclear. Here we report that maternal contribution of histone H3.3 assembly complexes can prevent the expression of late-onset anatomical, physiologic, and behavioral abnormalities of C. elegans. We show that mutants lacking hira-1, an evolutionarily conserved H3.3-deposition factor, have severe pleiotropic defects that manifest predominantly at adulthood. These late-onset defects can be maternally rescued, and maternally derived HIRA-1 protein can be detected in hira-1(−/−) progeny. Mitochondrial stress likely contributes to the late-onset defects, since hira-1 mutants display mitochondrial stress and the induction of mitochondrial stress results in at least some of the hira-1 late-onset abnormalities. A screen for mutants that mimic the hira-1 mutant phenotype identified PQN-80—a HIRA complex component, known as UBN1 in humans—and XNP-1—a second H3.3 chaperone, known as ATRX in humans. Furthermore, mutants lacking histone H3.3 have a late-onset defect similar to a defect of hira-1, pqn-80, and xnp-1 mutants. These data demonstrate that H3.3 assembly complexes provide non-DNA-based heritable information that can markedly influence adult phenotype. We speculate that similar maternal effects might explain the missing heritability of late-onset human diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and type 2 diabetes.

INTRODUCTION

Much of embryonic development is controlled by RNA and protein contributed by gametes to the zygote. The impact of this information is exemplified by maternal-effect mutants, which have been identified for a wide range of organisms, including, C. elegans [1], Drosophila [2], Xenopus [3], zebrafish [4], and mice [5]. For the vast majority of these mutants, animals that fail to inherit specific RNA from the oocyte have defects in embryonic development. If and how defects that manifest in adult animals can be maternally rescued is largely unknown. The elucidation of such maternal effects would be important for understanding the basic principles of inheritance and potentially important for understanding late-onset human disease.

Chromatin is assembled by histone chaperones. The HIRA complex and ATRX are two evolutionarily conserved histone chaperones that facilitate the deposition of the histone variant H3.3 onto chromatin in a DNA-replication independent process [6]. The HIRA complex consists of HIRA, UBN1, and CABIN1 [7]. This complex was first identified in S. cerevisiae, in which it represses histone gene transcription [8,9], and has been shown to deposit H3.3 at gene bodies and regulatory elements in animal cells [10]. ATRX functions with DAXX to deposit H3.3 at repetitive elements and telomeres [10]. Mutations in ATRX are the sole cause of ATRX (alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation X-linked) syndrome [11], and mutations in ATRX and H3.3 can drive cancer formation [12–15]. Thus, H3.3-containing chromatin is important for essential cellular processes in eukaryotes, and mutations in components of these complexes drive human disease. Nonetheless, much of what is known about HIRA, ATRX, and H3.3 derives from studies of cell culture, because loss of the HIRA complex, ATRX, or H3.3 results in embryonic lethality in many species [16–20]. We sought to understand the biological role of H3.3 assembly pathways by studying mutants that perturb this complex in C. elegans and discovered an unusual maternal effect: the inheritance of H3.3 assembly components via the maternal germline is sufficient to rescue defects that manifest near adulthood.

RESULTS

Loss of hira-1 results in late-onset defects

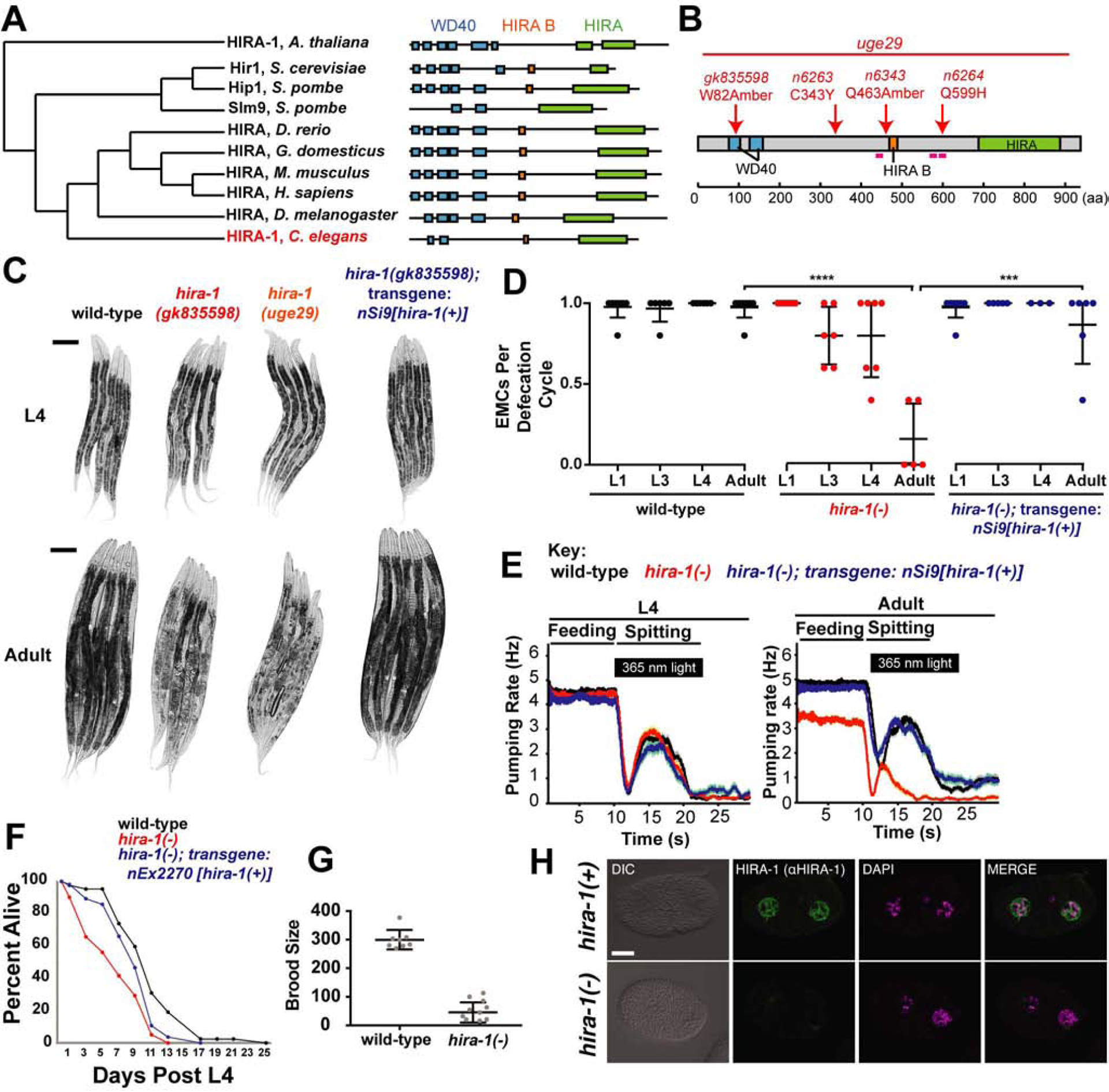

Like most eukaryotic genomes, the C. elegans genome contains a single ortholog of HIRA, the gene hira-1 (Figure 1A). To determine the normal biological role of hira-1, we examined the phenotype of a strain homozygous for a hira-1 early premature termination mutation, allele gk835598 (Figure 1B). Compared to adult wild-type animals, adult gk835598 animals were small and pale (Figures 1C, S1A), defective in the enteric muscle contraction (EMC) that is the final step of the defecation motor program (Figure 1D), defective in pharyngeal pumping (Figure 1E), short-lived (Figure 1F), and reduced in fertility (Figure 1G). The size, pigmentation, and pumping defects were detectable in only adult animals (Figures 1C, S1A, 1E), and the EMC defect was undetectable at the L1 larval stage and minor until adulthood (Figure 1D). Three lines of evidence indicate that these defects were caused by loss of hira-1 function and likely the null phenotype: (i) a strain with a deletion allele (uge29) [21] eliminating hira-1 mimicked the gk835598 strain for all aspects of the hira-1(gk835598) phenotype tested (Figures 1C, S1A); (ii) HIRA-1 protein as detected by immunofluorescence using two different antibodies raised against HIRA-1 was abolished in gk835598 embryos (Figures 1H, S1B); and (iii) introducing a wild-type copy of the hira-1 gene into hira-1(gk835598) mutants rescued all of these defects (Figures 1C, S1A, 1D, 1E, 1F). Taken together, these data indicate that loss of hira-1 results in pleiotropic defects that are minor or undetectable until adulthood and therefore will be referred to as “late-onset.” These data suggest that hira-1 is largely not required for normal embryonic and larval development but rather is specifically required for the normal physiology of adult animals.

Figure 1. Loss of hira-1 results in late-onset pleiotropic defects.

(A) Cladogram, adapted from TreeFam [50], of HIRA proteins in species indicated. (B) HIRA-1 domain organization with mutant alleles indicated. Magenta lines indicate peptide sequences used to raise anti-HIRA-1 antibodies. aa, amino acids. (C) Micrographs of five representative animals of the indicated genotypes at the L4 larval and adult stages. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) Fraction of defecation cycles with an enteric muscle contraction (EMC) in animals of the indicated genotypes at the indicated stages. Each data point represents a single animal for which five defecation cycles were scored; N≥3, mean +/− SD. (E) The pharyngeal feeding and light-evoked spitting behaviors of animals of the indicated genotypes and stages. The pharyngeal contraction (i.e., “pumping”) rate as a moving average is shown (N=60 animals). (F) Survival curves for animals of the indicated genotypes N≥41. (G) The number of progeny produced by animals of the indicated genotypes; N≥8, mean +/− SD. (H) Micrographs of wild-type and hira-1(gk835598) mutant 2-cell embryos stained with DAPI (magenta) and anti-HIRA-1 (green) antibody (rabbit 39215). Scale bar, 10 μm. See also Figure S1. hira-1(−) refers to the gk835598 allele

** P≤0.01,*** P≤0.001, **** P≤0.0001 by Student’s t-test

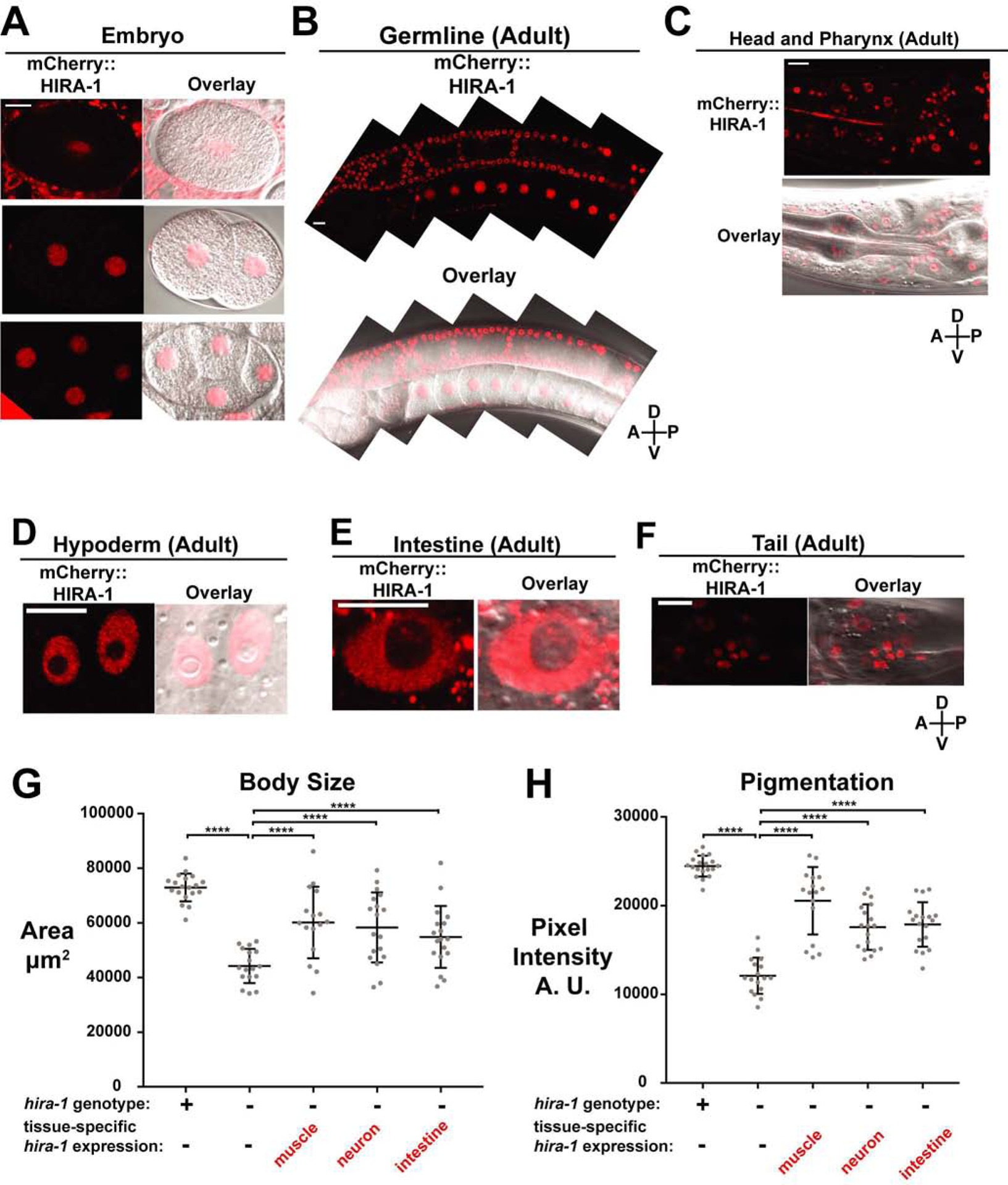

HIRA-1 can act in multiple cell types

To determine the cell types in which HIRA-1 acts to prevent these late-onset pleiotropic defects, we first examined the expression pattern of hira-1. We generated transgenic animals that express mcherry::hira-1 under the hira-1 promoter from a single-copy transgene integrated in the genome. This transgene was able to rescue hira-1 mutant defects (Figure S2A) and was detectable in many, if not all, cells throughout development and in adults (Figures 2A, 2B, 2C, 2D, 2E, 2F). Next we generated transgenic hira-1(−) lines that express hira-1(+) in a tissue-specific manner using promoters that drive expression in intestine, muscle, or neurons (Figure S2B). The small, pale, and pharyngeal pumping defects of hira-1 mutants were partially rescued by driving hira-1(+) expression in intestine, muscle or neurons (Figures S2C, 2G, 2H, S2D) indicating that hira-1 can function in multiple cell types. Given the broad hira-1 expression pattern, we suggest that hira-1 normally promotes a cell non-autonomous process that originates broadly through the animal and in at least intestinal cells, muscle, and neurons. The EMC defect was partially rescued by driving hira-1(+) expression in neurons and intestine but not muscle (Figure S2E), suggesting hira-1 normally functions in intestine and neurons but not muscle to maintain normal defecation behavior.

Figure 2. HIRA-1 is broadly expressed and can function in multiple cell types.

(A-F) Representative fluorescent and fluorescent/DIC overlay micrographs of mCherry::HIRA-1 expressed from a single-copy integrated transgene (nSi48: Phira-1::mCherry::hira-1) in the indicated cells, stages, and regions. Hypoderm nuclei in (D) are from hyp7. mCherry::HIRA-1 shows diffuse nuclear localization but is largely omitted from the nucleolus. (G, H) Wild-type animals, hira-1(−) animals, and hira-1(−) animals expressing transgenes driving hira-1(+) expression in muscle (nEx2902), neurons (nEx2892), or intestine (nEx2897) were scored for (G) body size and (H) pigmentation; mean +/− SD.

See also Figure S2.

Scale bars, 10 μm

hira-1(−) refers to the gk835598 allele

**** P≤0.0001 by Student’s t-test

Because hira-1 can function in intestinal cells, muscle or neurons we examined intestinal cells (which are easy to score) in hira-1 mutant larvae and adults. These mutants had a normal number of intestinal nuclei in both larvae and adults (Figure S2F). However, the morphology of some intestinal nuclei was abnormal in adults (Figure S2G, S2H). These data further suggest that embryonic and larval development are normal in hira-1 mutants and that the late-onset defects are occurring at the cellular level.

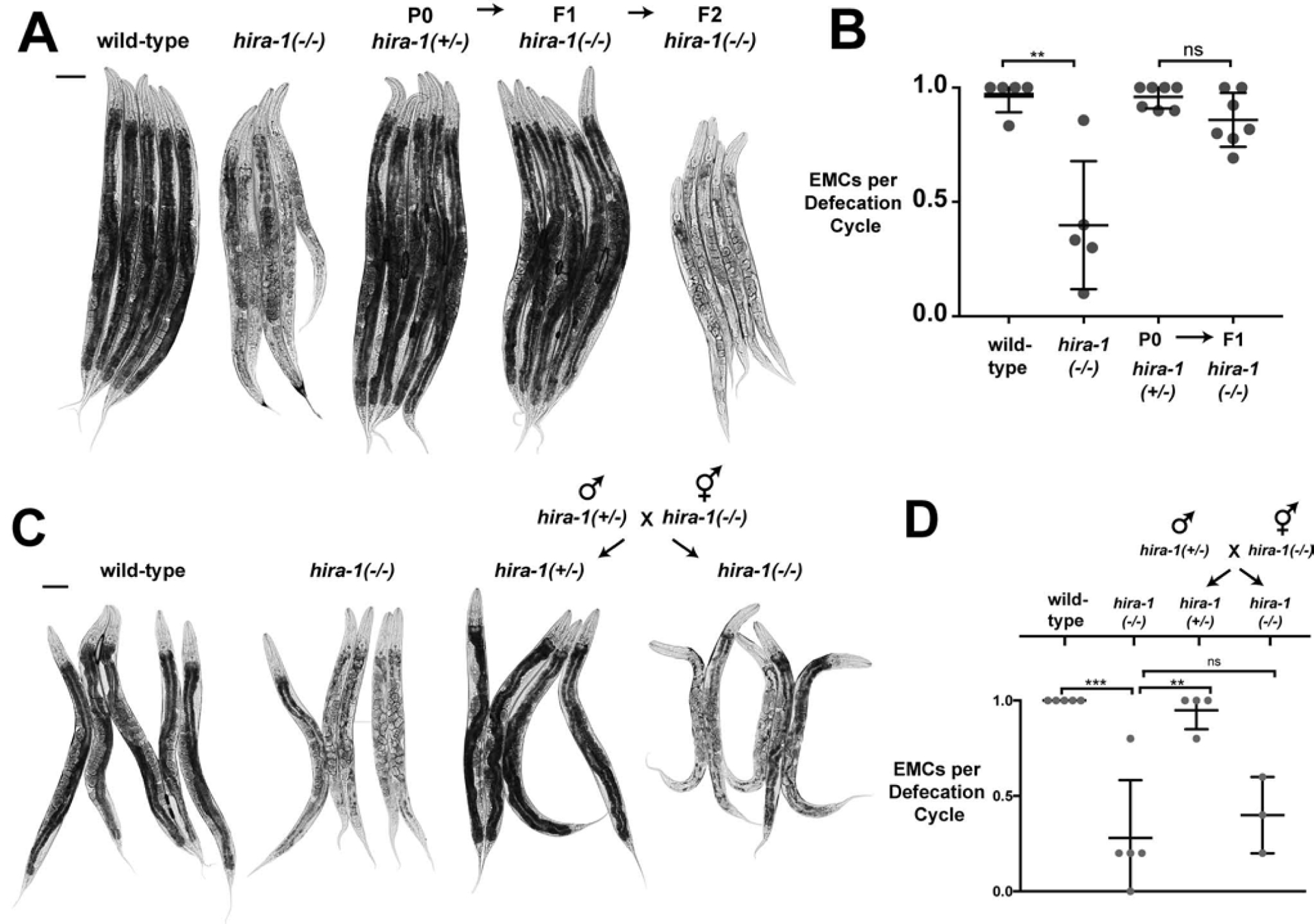

Maternally contributed HIRA-1 rescues late-onset defects

During backcrosses with hira-1 mutants we observed that the late-onset pleiotropies were parentally rescued. To confirm and quantify this finding, we examined hira-1(−/−) animals generated by hira-1(+/−) hermaphrodite parents; these hira-1(−/−) animals were indistinguishable from wild-type animals with respect to the small, pale, and defecation defects (Figures 3A, S3A, S3B, 3B), indicating that the late-onset defects of hira-1 mutants were parentally rescued. To determine if hira-1 mutant defects were paternally or maternally rescued (or both), we analyzed hira-1(−/−) progeny generated by hira-1(−/−) hermaphrodites crossed with hira-1(+/−) fathers (Figure 3C). These animals still had the small, pale, and defecation defects (Figures 3C, S3C, S3D, 3D), indicating that hira-1 mutant defects were not paternally rescued. Furthermore, hira-1(+/−) progeny generated from hira-1(−/−) mothers and hira-1(+/−) fathers did not have the small, pale, or defecation defects (Figures 3C, S3C, S3D, 3D), indicating that hira-1 mutant defects were zygotically rescued. The brood-size defect of hira-1 mutants was not parentally rescued (Figure S3E). Consistent with the maternal rescue of hira-1 mutants, mCherry::HIRA-1 protein was detectable in embryos and adults that did not carry this transgene in their genomes but were generated by mothers heterozygous for the transgene (Figure S3F, S3G, S3H). To detect maternally derived HIRA-1 in adults, we needed to increase the intensity of the laser and exposure to levels that saturate the signal of the non-maternally derived control. Thus, the maternally derived HIRA-1 protein in adults was barely detectable and far lower than that seen at earlier stages. In addition, we detected HIRA-1 protein in mature oocytes and embryos prior to zygotic activation (Figure 1H, 2A, 2B). These data indicate that HIRA-1 (mRNA or protein) can be inherited via the maternal germline, and that inherited HIRA-1 can rescue late-onset defects of hira-1 mutants.

Figure 3. The late-onset defects of hira-1 mutants are maternally rescued.

(A) Micrographs of five representative adult animals of the indicated genotypes and generations. hira-1(+/−) signifies hira-1(gk835598) / qC1. qC1 is a balancer chromosome (carrying hira-1(+)) that suppresses recombination on the left arm of chromosome III and was used to maintain the hira-1(gk835598) mutation in heterozygotes [51]. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Fraction of EMCs per defecation cycle of adult animals of the indicated genotypes and generations; N=5, mean +/−SD. (C) Micrographs of representative adult control animals (wild-type and hira-1(−)) and adult progeny of the indicated genotype from the indicated cross. Scale bar, 100 μm. Males from the indicated cross carry an X-linked gfp (ccIs4810: lmn-1::gfp) to identify cross progeny hermaphrodites. hira-1(+/−) signifies hira-1(gk835598) / qC1. (D) Fraction of EMCs per defecation cycle of adult animals of the indicated genotypes as in (C). Males from the indicated cross carry an X-linked gfp (ccIs4810: lmn-1::gfp) to identify cross progeny hermaphordites. hira-1(+/−) signifies hira-1(gk835598) / qC1.; N≥3, mean +/− SD. See also Figure S3.

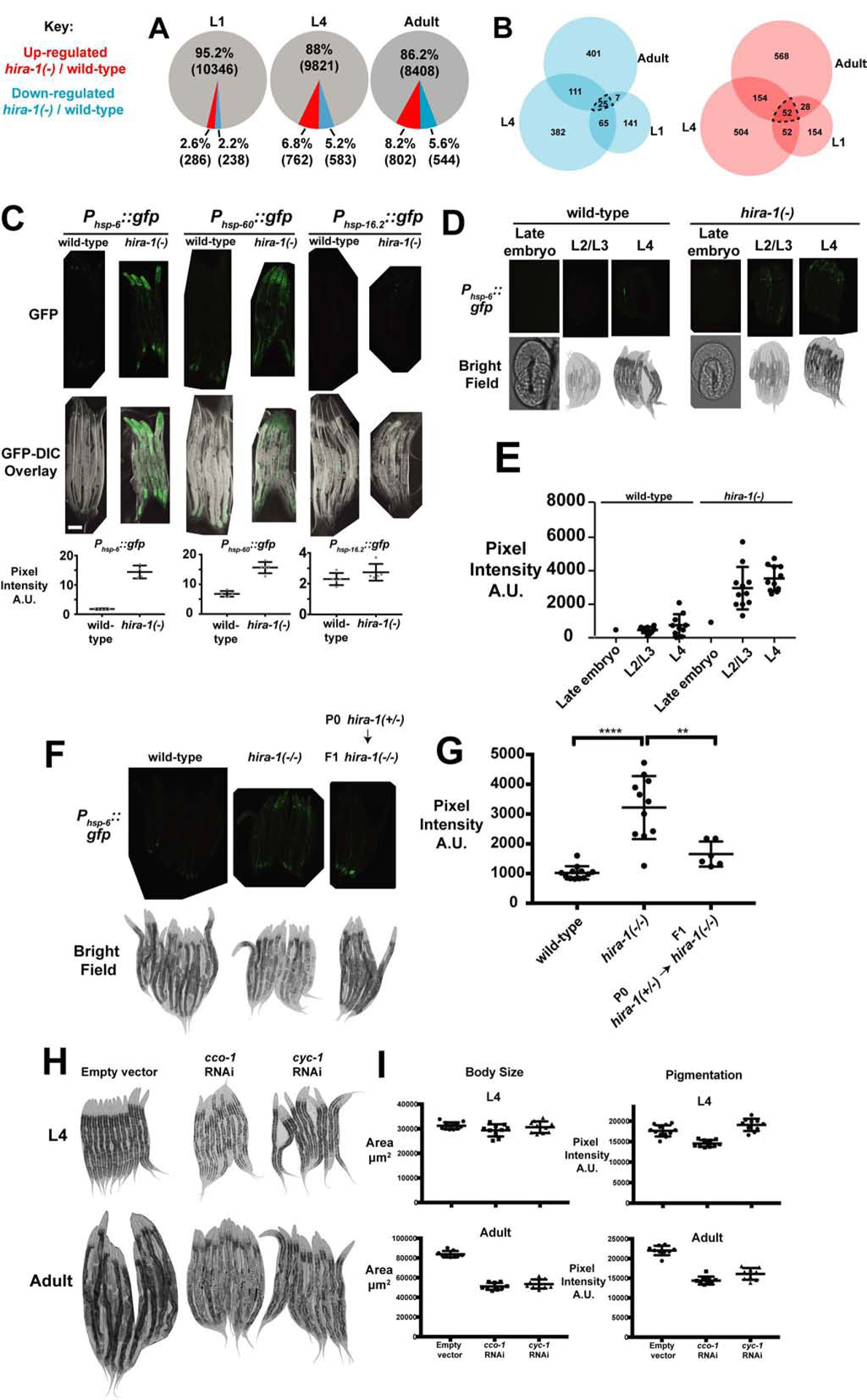

Loss of hira-1 results in chronic mitochondrial stress

To better understand the molecular defects of hira-1 mutants, we performed RNA-seq of wild-type and hira-1 mutants at three developmental stages: L1, L4, and adult. While hira-1 mutant abnormalities predominantly manifested at the onset of adulthood, we were able to detect significant gene expression changes in hira-1 mutants prior to the onset of adulthood (stages L1 and L4, Figure 4A, Table S1), suggesting that the chronic misexpression of genes over time might result in the late-onset defects. We focused on chronically misexpressed genes, namely genes that were misexpressed in the same direction in all three stages (77 genes, Figures 4B dotted line, S4A, S4B). Using WormExp [22] we compared the chronically misexpressed genes with 2,293 previously published C. elegans gene expression profiles from studies of a broad range of biological contexts. Six of the top 15 hits from this analysis were from animals undergoing mitochondrial insults (Figure S4C). That hira-1 mutants have a gene-expression profile similar to those of animals undergoing mitochondrial insults suggested that hira-1 mutants are experiencing mitochondrial stress. Supporting this hypothesis, we observed that hira-1 mutants showed activation of two different reporters of mitochondrial stress (Phsp-6::gfp and Phsp-60::gfp) but no activation of a reporter for the cytosolic heat-shock response (Phsp-16.2::gfp) (Figure 4C). The mitochondrial stress response was activated throughout development (Figure 4D, 4E). Like the late-onset defects of hira-1 mutants, activation of the mitochondrial stress response was maternally rescued (Figure 4F, 4G). Thus, loss of hira-1 results in chronic activation of the mitochondrial stress response. Others have reported that mitochondrial stress can result in animals that have late-onset small and pale defects [23–25], like hira-1 mutants. Similarly, we found that RNAi targeting cco-1 and cyc-1 (two different mitochondrial components) led to late-onset small and pale defects (Figure 4H, 4I). We conclude that mitochondrial stress likely drives at least some aspects of the late-onset defects of hira-1 mutants.

Figure 4. Loss of hira-1 Results in Chronic Activation of the Mitochondrial Stress Response.

(A) Genes that change expression in hira-1(−) compared to wild-type animals. Red, genes up-regulated (at least 2-fold, P<0.01); blue, genes down-regulated (at least 2-fold, P<0.01); and grey, all other genes. (B) Venn diagrams representing overlap between genes down-regulated at the indicated stages (blue) and overlap between genes up-regulated in the indicated stages (red). (C) Top row, fluorescent micrographs of five representative adults of the indicated genotypes expressing the indicated stress reporters. Middle row, GFP-DIC overlay micrographs of the animals imaged above. Bottom row, quantification of the GFP signal from animals above; N≥4, mean +/− SD. (D) Phsp-6::gfp fluorescence (top) and bright-field (bottom) micrographs of embryos or animals of the indicated genotypes at the indicated stages. (E) Quantification of the GFP signal from embryos and animals in (D); mean +/− SD. (F) Phsp-6::gfp fluorescence (top) and bright-field (bottom) micrographs of adults of the indicated genotypes and generation. (G) Quantification of GFP signal from animals in (F); mean +/− SD. (H) Micrographs of 9–12 representative wild-type animals of the indicated stages undergoing RNAi to the indicated genes or no RNAi (empty vector). (I) Quantification of the body size and pigmentation of the animals imaged in (H); mean +/− SD. See also Figure S4 and Table S1.

hira-1(−) refers to the gk835598 allele

** P≤0.01, **** P≤0.0001 by Student’s t-test

Loss of hira-1 results in up-regulation of histone gene expression

We noted that 25% (13/52) of the chronically up-regulated genes in hira-1 mutants encode histones (Figure S4A); that of the 39 histone genes with expression levels we were able to detect, 35 were up-regulated in at least one developmental stage (Figure S4D); and that on average histone gene expression in hira-1 adults was 11-fold higher than in wild-type animals (with a median of 26-fold higher) (Figure S4D). The number of histones we were able to detect was limited by the high sequence identity shared by histone genes, which leads to difficulty in unambiguously mapping reads to individual histone genes. Our RNA-seq analysis was done on polyA-selected RNA. Mangone et al. (2010) [26] identified polyadenylation of transcripts of most histone genes in C. elegans. 35 of the 39 histone genes we detected as expressed were found to be polyadenylated in this paper. We conclude that loss of hira-1 results in a striking up-regulation of histone gene expression. In yeast, the Hir complex assembles nucleosomes at histone gene promoters to repress histone gene expression outside of S-phase [8,9,27]. We propose that in C. elegans HIRA-1 plays a similar role in repressing histone gene expression. Alternatively, it is possible that a failure to assemble nucleosomes in hira-1 mutants causes cells to compensate and up-regulate histone gene expression.

A screen for mutants similar to hira-1 mutants identified components of H3.3 chromatin assembly complexes

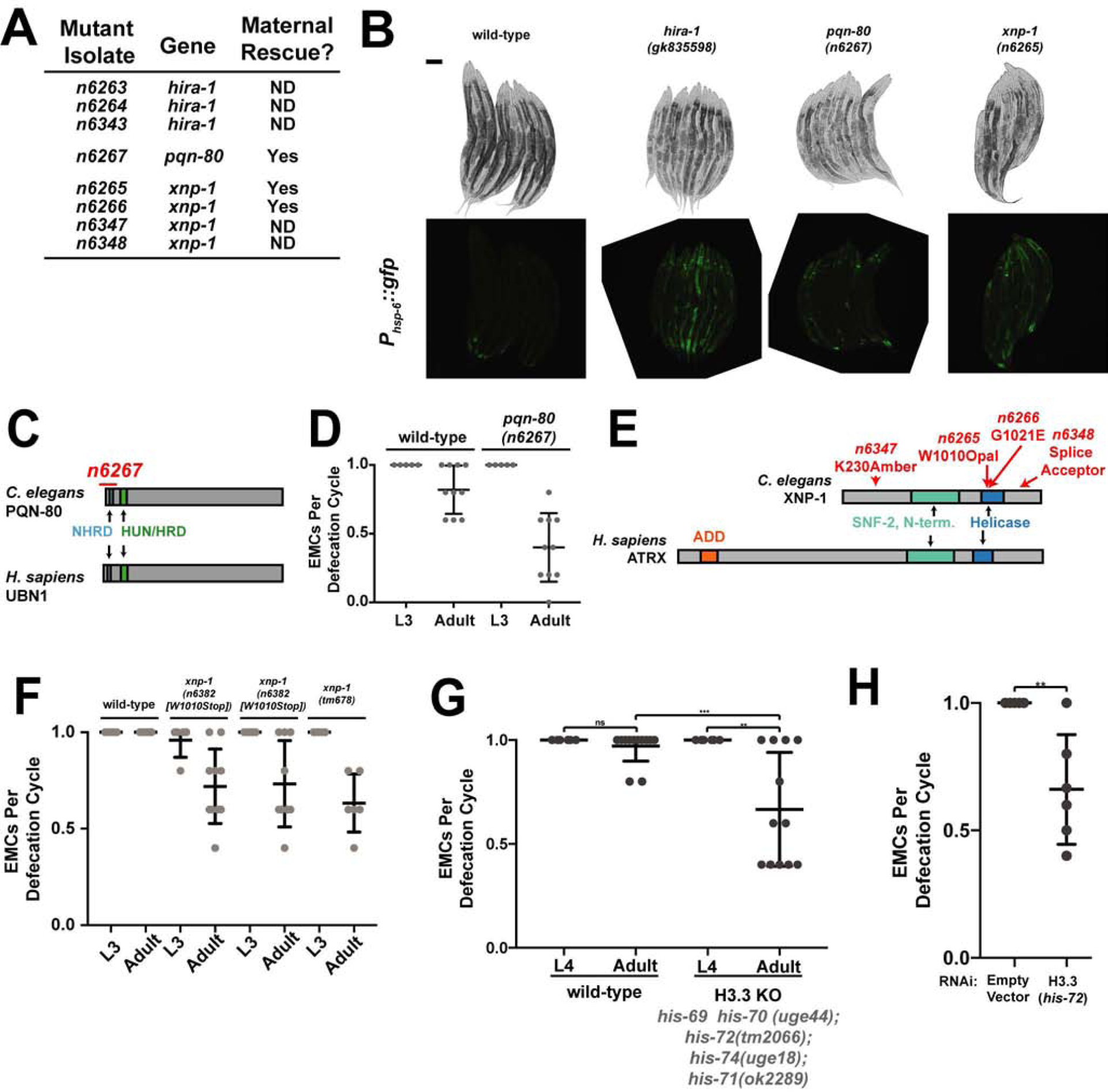

To better understand why hira-1 function is needed for diverse late-stage characteristics, we sought other genes that function similarly to hira-1. We performed an EMS mutagenesis screen for mutants that like hira-1 mutants are small, pale, and misexpress Phsp-6::gfp (a mitochondrial stress reporter activated in hira-1 mutants) (Figures S5A; 4C). We reasoned that by using these three aspects of the hira-1 phenotype to screen, we would specifically enrich for mutants similar to hira-1 mutants. We screened in the F3 generation, because these mutant defects are maternally rescued. We identified three new alleles of hira-1 (Figures 5A, 1B, S5B), validating the screen and confirming our phenotypic analyses. We also identified a deletion allele of pqn-80 (Figures 5A, 5B, 5C). Interpro [28] analysis of the PQN-80 sequence identified a HUN/HRD domain (Figures S5C, 5C). The HUN/HRD domain is defined by a core member of the HIRA complex known as UBN1 in humans and HPC2 in yeast [29]. We propose that PQN-80 is the C. elegans ortholog of UBN1 and HPC2. Our screen also identified four alleles of the ATRX homolog gene xnp-1 (Figures 5A, 5B, S5B, 5E). pqn-80 and xnp-1 mutants had maternally rescued small and pale defects similar to those of hira-1 mutants (Figure 5A, 5B, S5B). Additionally, like hira-1 mutants, pqn-80 and xnp-1 mutants had late-onset defects in defecation (Figure 5D, 5F). In short, pqn-80 and xnp-1 mutants are nearly identical in phenotype to hira-1 mutants. In Drosophila, Hira and Xnp can be recruited to the same genomic sites [30]. Given the similarities of phenotypes of hira-1 and xnp-1 mutants, we propose that the misregulation of common targets leads to similar phenotypic defects.

Figure 5. A screen for mutants that mimic hira-1 mutants identified components of H3.3 chromatin assembly complexes.

(A) Some of the mutant isolates identified in the screen. ND, not determined. (B) Bright-field (top) and Phsp-6::gfp fluorescence (bottom) micrographs of 8–10 representative animals of the indicated genotypes. (C) Domain organization of C. elegans PQN-80 and human UBN-1, showing the n6267 deletion allele of pqn-80 identified from the screen (red). (D) Fraction of defecation cycles with an enteric muscle contraction in animals of the indicated genotypes at the indicated developmental stages. These strains contain Phsp-6::gfp. N≥5, mean +/− SD. (E) Domain organizations of C. elegans XNP-1 and human ATRX showing alleles of xnp-1 identified in the screen (red). ADD is an H3-binding module to which binding is promoted by H3 lysine 9 trimethylation [52]. (F, G) Fraction of defecation cycles with an enteric muscle contraction was scored in animals of the indicated genotypes at the indicated developmental stages; N≥5, mean +/− SD. (H) Fraction of defecation cycles with an enteric muscle contraction in wild-type adult animals exposed to dsRNA targeting the indicated gene; N≥5, mean +/− SD. See also Figure S5. Scale bars, 100 μm

The HIRA complex and ATRX have well-established roles as H3.3 chaperones. We next asked if animals lacking H3.3 share abnormalities with hira-1, pqn-80 and xnp-1 mutants. C. elegans has five H3.3-like genes [31]. A quintuple mutant lacking all five H3.3 genes [21] did not have defects in body size or pigmentation (Figure S5D) but did have a late-onset defect in defecation (Figure 5G). A similar defect was produced by RNAi against the H3.3 gene his-72 (Figure 5H). We also observed activation of a mitochondrial stress reporter after RNAi against his-72 (S5E). The difference between the defects observed in the H3.3 assembly factor mutants and the H3.3 mutant might be explained by the ability of H3 to compensate for loss of H3.3, a phenomenon observed for Drosophila [32].

Our data establish that mutants lacking components of H3.3 assembly complexes have maternally rescued late-onset defects at least some of which are likely caused by mitochondrial stress.

DISCUSSION

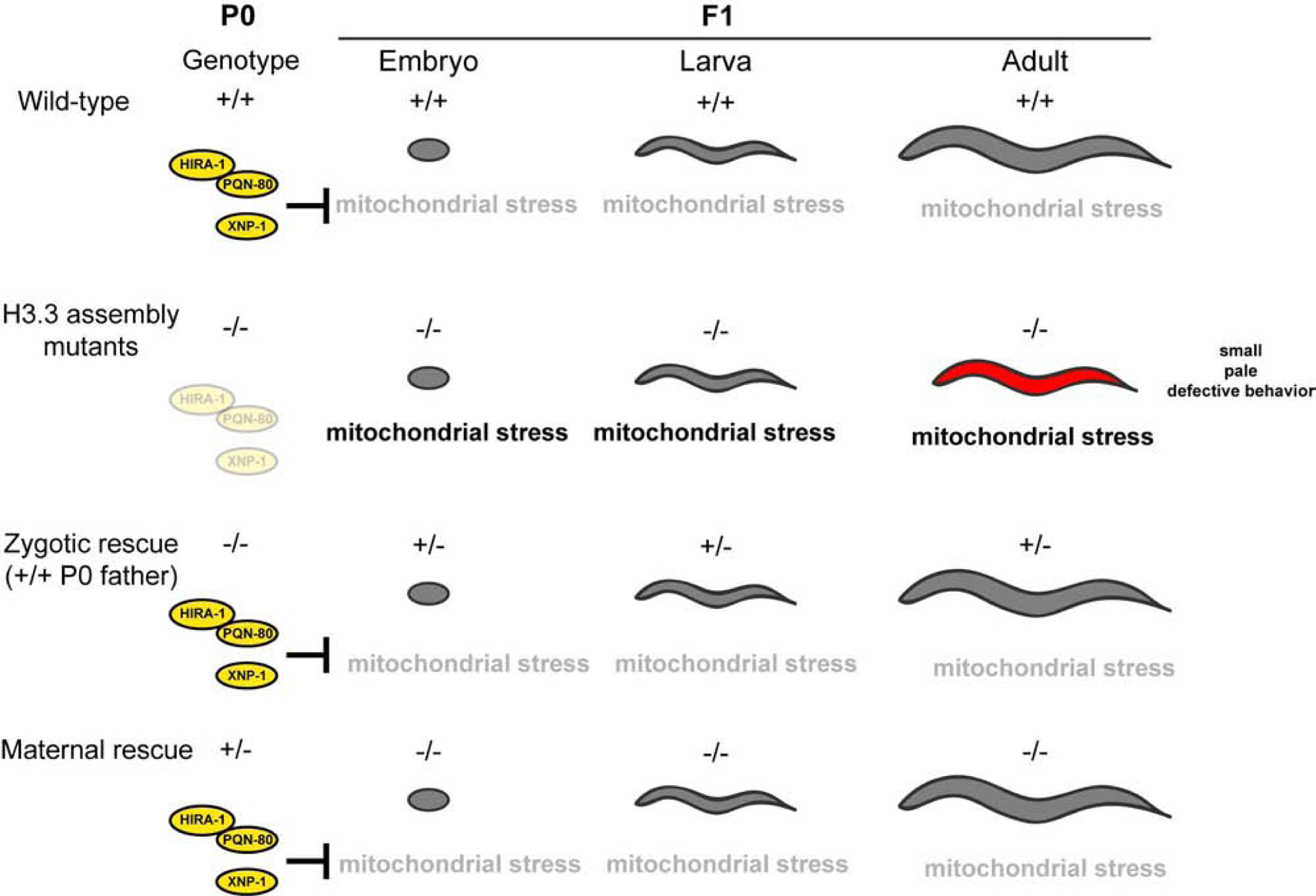

Whereas most maternal-effect mutants have defects in embryonic development [1–5], mutants in hira-1, pqn-80, and xnp-1 have maternally rescued defects that manifest near the onset of adulthood. Embryonic and larval development are largely normal in these H3.3 assembly mutants, but near the onset of adulthood there appears to be a failure of multiple cell types. We propose that chronic mitochondrial stress drives much of this cellular dysfunction and that the inheritance of H3.3 assembly factors via the maternal germline is sufficient to provide lifelong protection from mitochondrial stress (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Maternal H3.3 assembly complexes are sufficient to prevent late- onset defects.

Loss of H3.3 assembly factors results in pleiotropic defects that manifest near the onset of adulthood. These defects are likely caused by chronic mitochondrial stress. Inheriting these factors through the maternal germline is sufficient to rescue these late-onset defects.

H3.3 assembly mutants display a prolonged maternal effect

The defects of H3.3 assembly mutants in body size, pigmentation, pharyngeal pumping and defecation are minor or undetectable until adulthood, suggesting that the cells that control these processes develop and function normally in the embryo and larvae. Consistent with this view, we observed that intestinal cells (in which hira-1 can act to rescue the late-onset defects) did not display any obvious developmental abnormalities in embryos or larvae but did become morphologically abnormal in adults. We propose that the late-onset defects of H3.3 assembly mutants are not caused by embryonic or larval developmental defects but rather by late-onset cellular dysfunction. We note that maternal effects that impact stages after embryonic development have been described for C. elegans [33,34], snail [35], zebrafish [36], and mouse [37] indicating the impact of maternal effects on later life stages can occur in a range of organisms.

What is the mechanism behind the long-lasting maternal effect?

Mechanistically, how might maternally contributed HIRA-1 prevent mitochondrial stress throughout embryonic development and into adulthood? We were able to detect maternally derived HIRA-1 in adult animals. Although the level in adults appeared to be far lower than that in embryos, it is conceivable that the maternally derived protein that persists into adults is sufficient to rescue the late-onset defects. We prefer an alternative hypothesis -- maternally derived HIRA-1 establishes in embryos a chromatin state that can persist into adult animals. H3.3 and its assembly factors are maternally contributed in Drosophila [16], Xenopus [38], and mice [17,39,40]. HIRA and ATRX have been shown to deposit H3.3 onto chromatin in embryonic stem cells [41–43] and during early embryonic development in Drosophila [16], Xenopus [38], and mice [17,44,45]. After somatic nulcei are implanted into enucleated eggs of Xenopus, H3.3 is required for maintaining an epigenetic memory of gene expression that can persist through 24 mitotic divisions [46]. We speculate that epigenetic states established by the deposition of H3.3 in the early embryo impact gene expression throughout much of the lifespan of many organisms and that this altered gene expression can impact phenotype later in life.

Parental effects on late-onset disease might be underappreciated

Although a parental effect can impact lifespan in C. elegans [47] and a paternal effect can impact cancer formation in adult mice [48], relative to maternal effects that affect early embryonic development, parental effects that impact phenotypes that manifest at adulthood appear to be rare. Much of the heritability of many late-onset diseases -- including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and cancer -- cannot be explained by changes in DNA sequence. We speculate that parental effects might be underappreciated in our understanding of the genetics of these and other human diseases in which the phenotypic impact of non-inherited alleles is often ignored [49].

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, H. Robert Horvitz (horvitz@mit.edu).

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact without restriction.

Data and Code Availability

RNA-seq data are available at the GEO: GSE144686

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

C. elegans strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. Strains were maintained at 20°C on Nematode Growth Medium plates containing 3 g/L NaCl, 2.5 g/L peptone and 17 g/L agar supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM KPO4 and 5 mg/L cholesterol with E. coli OP50 as a source of food [53]. hira-1(−) indicates hira-1(gk835598). All measurements were taken from hermaphrodite animals.

METHOD DETAILS

Microscopy

Bright field, Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) and epifluorescence images were obtained using Axio Imager.Z2 (Zeiss) and LSM 800 (Zeiss) microscopes. Images were processed using FIJI (NIH) and Photoshop (Adobe).

Plasmid and transgenic strain construction

Transgene nSi48: Phira-1::mcherrydpiRNAhira-1 ::hira-1::hira-1 3’UTR

In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara) was used to fuse the following PCR products: Phira-1 (1003 bp directly 5’ of hira-1 ATG), mcherrydpiRNA (lacks piRNA target sites to avoid transgene silencing in the germline [54]), hira-1 gene (includes introns and 3’ UTR, 4928 bp), pCJF350 MosSci plasmid targeting ttTi5605 (insertion site on chromosome II). This construct was injected at 10 ng/μl and integrated into chromosome II using MosSci [55].

Transgene nEx2902: Pmyo-3::mcherry::F2A::hira-1 cDNA::tbb-2 3’UTR

In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara) was used to fuse the following PCR products: Pmyo-3 [56], mcherry (from pCFJ104, www.wormbuilder.org), hira-1 cDNA, tbb-2 3’ UTR (from pCFJ420, www.wormbuilder.org). This construct was injected at 20 ng/μl concentration with co-injection marker pCFJ420 (10 ng/μl, www.wormbuilder.org).

Transgene nEx2892: Prab-3::mcherry::F2A::hira-1 cDNA::tbb-2 3’UTR

In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara) was used to fuse the following PCR products: Prab-3 [57], mcherry (from pCFJ104, www.wormbuilder.org), hira-1 cDNA, tbb-2 3’ UTR (from pCFJ420, www.wormbuilder.org). This construct was injected at 20 ng/μl concentration.

Transgene nEx2897: Pvha-6::mcherry::F2A::hira-1 cDNA::tbb-2 3’UTR

In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara) was used to fuse the following PCR products: Pvha-6 [58], mcherry (from pCFJ104, www.wormbuilder.org), hira-1 cDNA, tbb-2 3’ UTR (from pCFJ420, www.wormbuilder.org). This construct was injected at 20 ng/μl concentration with co-injection marker pCFJ420: Peft-3::h2b::gfp (10 ng/μl, www.wormbuilder.org).

Transgene nSi28: Pmyo-3::3xFLAG::hira-1::tbb-2 3’UTR

In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara) was used to fuse the following PCR products: Pmyo-3 [56], 3x FLAG, hira-1 gene (includes introns), tbb-2 3’ UTR (from pCFJ420, www.wormbuilder.org), pCJF350 MosSci plasmid targeting ttTi5605 (insertion site on chromosome II). This construct was injected at 10 ng/μl and integrated into chromosome II using MosSci [55].

Transgene nSi23: Prab-3::3xFLAGhira-1::tbb-2 3’UTR

In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara) was used to fuse the following PCR products: Prab-3 [57], 3xFLAG, hira-1 gene (includes introns), tbb-2 3’ UTR (from pCFJ420, www.wormbuilder.org), pCJF350 MosSci plasmid targeting ttTi5605 (insertion site on chromosome II). This construct was injected at 10 ng/μl and integrated into chromosome II using MosSci [55].

Transgene nSi21: Pges-1::3xFLAG::hira-1::tbb-2 3’UTR

In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara) was used to fuse the following PCR products: Pges-1 [59], 3x FLAG, hira-1 gene (includes introns), tbb-2 3’ UTR (from pCFJ420, www.wormbuilder.org), pCJF350 MosSci plasmid targeting oxTi185 (insertion site on chromosome I). This construct was injected at 10 ng/μl and integrated into chromosome II using MosSci [55].

Defecation

The enteric muscle contraction (EMC) that executes the expulsion step of the defecation motor program was observed using a dissecting microscope. The fraction of EMCs per five cycles per worm was measured.

Genetic screen and mutation identification

SJ4100 L4 larvae were mutagenized as described previously [53]. F3 animals were chosen based on three defects exhibited by hira-1 mutants: small, pale, and misexpression of Phsp-6::gfp. Mutants were backcrossed, mutations were mapped using SNP mapping [60], and genomic DNA from mutant isolates was analyzed by whole-genome sequencing.

Pharyngeal pumping

Two distinct pharyngeal behaviors were measured: feeding pumps, which occur when animals are left undisturbed in the presence of food (t=0 to t=10 ), and spitting pumps, which occur as a response to noxious 365 nm light [61].

Antibody production

Two anti-HIRA-1 antibodies were generated by Pocono Rabbit Farm and Laboratory (32915 and 32916). The three peptide sequences KSMEDNSKENESKNSEK, PALRPMEPKSLKTQEGT, and EAPEQQPKLSQHVVDRK (Figure 1B indicates location of peptides) were injected. Antisera were collected from two rabbits, and antibodies were affinity purified.

RNA-Seq

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). mRNA was purified by polyA-tail enrichment, fragmented, and reverse transcribed into cDNA (Illumina TruSeq). cDNA samples were then end repaired, adaptor-ligated using the SPRI-works Fragment Library System I (Beckman Coulter Genomics) and indexed during amplification. Libraries were quantified using the Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical) and qPCR before being loaded for paired-end sequencing using the Illumina NextSeq sequencer. RNA-seq data were aligned and summarized using bowtie version 1.0.1 [62], RSEM version 1.2.15 [63], samtools/0.1.19 [64] and a UCSC known genes annotation file from the ce10 assembly. Differential expression analysis was done with R version 2.15.3 using DESeq_1.10.1 [65]. For the genes and fold changes reported in Figures 4 and S4, our cutoff was an average of at least 5 FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) per gene, applied to each genotype independently. The p-value cutoffs reported for the fold changes in Figures 4 and S4 were calculated using DESeq and take into account multiple testing.

Quantification of body size and pigmentation

Micrographs of whole worms were analyzed using FIJI. The perimeter was traced around each individual worm. The area within the perimeter was calculated and used to define the body size of each worm. The pixel intensity was also determined for the area inside the perimeter traced for each worm. For the calculation of pixel intensities, the pixel intensities of original micrographs were inverted. For example, the wild-type strain has darker pigmentation and when inverted has a higher value for pixel intensity. The background (selected from an arbitrary area of the micrograph that did not contain worms) from each image was subtracted from each measurement of pixel intensity.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For all quantification error bars represent standard deviation (SD). Student’s t tests were used to determine statistical significance. Graphs and indicated statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 7 software.

Supplementary Material

Table S2. C. elegans strains used in this study. Related to STAR methods. The C. elegans strains used in this study.

Table S1. Gene expression changes in hira-1 mutants. Related to Figure 4. Genes that change expression in hira-1(-) compared to wild-type animals at the indicated stages. UP, indicates genes up-regulated (at least 2-fold, P<0.01); DOWN, indicates genes down-regulated (at least 2-fold, P<0.01). The log2 fold change and p-values are listed for each gene. The genes in this table correspond to the red and blue areas of the pie-charts and Venn diagrams in Figure 4.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HIRA-1 (32915) | This paper | N/A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HIRA-1 (39216) | This paper | N/A |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli: OP50 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | RRID:WB-STRAIN:OP50–1 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| TRIzol Reagent | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#: 15596018 |

| Chemical: Ethyl methanesulfonate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: M0880 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| In-Fusion HD Cloning System | TaKaRa | Cat#: 639637 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: Phira-1::mcherrydpiRNA::hira-1::hira-1 3’UTR | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: Pmyo-3::mcherry::F2A::hira-1 cDNA::tbb-2 3’UTR | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: Prab-3::mcherry::F2A::hira-1 cDNA::tbb-2 3’UTR | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: Pvha-6::mcherry::F2A::hira-1 cDNA::tbb-2 3’UTR | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: Pmyo-3::3xFLAG::hira-1::tbb-2 3’UTR | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: Prab-3::3xFLAGhira-1::tbb-2 3’UTR | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: Pges-1::3xFLAG::hira-1::tbb-2 3’UTR | This paper | N/A |

| Deposited Data | ||

| RNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE144686 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans | This paper | Table S2 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Image J | NIH image | SCR_003070 |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 |

| Zen | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/downloads/zen.html |

Highlights.

Loss of H3.3 assembly factors results in late-onset defects.

Mitochondrial stress likely contributes to these late-onset defects.

The late-onset defects of H3.3 assembly mutants can be maternally rescued.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Doi, N. Burton, C. Pender, C. Engert, V. Dwivedi, N. Bhatla, S. Luo, and other members of the Horvitz laboratory for discussions; F. Steiner for sharing strains; and the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440) for strains. K.B. was supported by the Life Sciences Research Foundation (sponsored by Sanofi). H.R.H. is the David H. Koch Professor of Biology at MIT and an Investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported by NIH grant R01GM024663.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowerman B (1998). Maternal Control of Pattern Formation in Early Caenorhabditis elegans Embryos. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol 39, 73–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luschnig S, Moussian B, Krauss J, Desjeux I, Perkovic J, and Nüsslein-Volhard C (2004). An F1 genetic screen for maternal-effect mutations affecting embryonic pattern formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 167, 325–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Droin A (1992). The developmental mutants of Xenopus. Int. J. Dev. Biol 36, 455–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dosch R (2015). Next generation mothers: Maternal control of germline development in zebrafish. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 50, 54–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condic ML (2016). The Role of Maternal-Effect Genes in Mammalian Development: Are Mammalian Embryos Really an Exception? Stem Cell Rev. Rep 12, 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond CM, Strømme CB, Huang H, Patel DJ, and Groth A (2017). Histone chaperone networks shaping chromatin function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18, 141–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricketts MD, and Marmorstein R (2017). A molecular prospective for HIRA complex assembly and H3.3-specific histone chaperone function. J. Mol. Biol 429, 1924–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu H, Kim UJ, Schuster T, and Grunstein M (1992). Identification of a new set of cell cycle-regulatory genes that regulate S-phase transcription of histone genes in Saccharomyces cerrevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol 12, 5249–5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osley MA, and Lycan D (1987). Trans-acting regulatory mutations that alter transcription of Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone genes. Mol. Cell. Biol 7, 4204–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grover P, Asa JS, and Campos EI (2018). H3–H4 Histone Chaperone Pathways. Annu. Rev. Genet 52, 109–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons RJ, and Higgs DR (2000). Molecular–clinical spectrum of the ATR-X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet 97, 204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyer MA, Qadeer ZA, Valle-Garcia D, and Bernstein E (2017). ATRX and DAXX: Mechanisms and mutations. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu X-Y, Jones DTW, Pfaff E, Jacob K, Sturm D, Fontebasso AM, Quang D-AK, Tönjes M, et al. (2012). Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature 482, 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J, Qu C, Ding L, Huether R, Parker M, et al. (2012). Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Nat. Genet 44, 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behjati S, Tarpey PS, Presneau N, Scheipl S, Pillay N, Van Loo P, Wedge DC, Cooke SL, Gundem G, Davies H, et al. (2013). Distinct H3F3A and H3F3B driver mutations define chondroblastoma and giant cell tumor of bone. Nat. Genet 45, 1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loppin B, Bonnefoy E, Anselme C, Laurençon A, Karr TL, and Couble P (2005). The histone H3.3 chaperone HIRA is essential for chromatin assembly in the male pronucleus. Nature 437, 1386–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin CJ, Koh F, Wong P, Conti M, and Ramalho-Santos M (2014). Hira-mediated H3.3 incorporation is required for DNA replication and ribosomal RNA transcription in the mouse zygote. Dev. Cell 30, 268–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang MY, Guo QH, Du XZ, Zhou L, Luo Q, Zeng QH, Wang JL, Zhao H Bin, and Wang YF (2014). HIRA is essential for the development of gibel carp. Fish Physiol. Biochem 40, 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrick D, Sharpe JA, Arkell R, Dobbie L, Smith AJH, Wood WG, Higgs DR, and Gibbons RJ (2006). Loss of Atrx affects trophoblast development and the pattern of X-inactivation in extraembryonic tissues. PLOS Genet 2, e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang MCW, Jacobs SA, Mattiske DM, Soh YM, Graham AN, Tran A, Lim SL, Hudson DF, Kalitsis P, O’Bryan MK, et al. (2015). Contribution of the two genes encoding histone variant H3.3 to viability and fertility in mice. PLOS Genet 11, e1004964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaney K, Mailler J, Wenda JM, Gabus C, and Steiner FA (2018). Differential expression of histone H3.3 genes and their role in modulating temperature stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 209, 551 LP–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wentao Y, Dierking K, and Schulenburg H (2016). WormExp: a web-based application for a Caenorhabditis elegans-specific gene expression enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics 32, 943–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillin A, Hsu A-L, Arantes-Oliveira N, Lehrer-Graiwer J, Hsin H, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, and Kenyon C (2002). Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science 298, 2398–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang W, and Hekimi S (2010). Two modes of mitochondrial dysfunction lead independently to lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 9, 433–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rea SL, Ventura N, and Johnson TE (2007). Relationship between mitochondrial electron transport chain dysfunction, development, and life extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 5, 2312–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangone M, Manoharan AP, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Han T, Mackowiak SD, Mis E, Zegar C, Gutwein MR, Khivansara V, et al. (2010). The Landscape of C. elegans 3′UTRs. Science 329, 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fillingham J, Kainth P, Lambert J-P, van Bakel H, Tsui K, Peña-Castillo L, Nislow C, Figeys D, Hughes TR, Greenblatt J, et al. (2009). Two-Color Cell Array Screen Reveals Interdependent Roles for Histone Chaperones and a Chromatin Boundary Regulator in Histone Gene Repression. Mol. Cell 35, 340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell AL, Sangrador-Vegas A, Luciani A, Madeira F, Nuka G, Salazar GA, Chang H-Y, Richardson LJ, Qureshi MA, Fraser MI, et al. (2018). InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D351–D360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ricketts MD, Frederick B, Hoff H, Tang Y, Schultz DC, Rai TS, Vizioli MG, Adams PD, and Marmorstein R (2015). Ubinuclein-1 confers histone H3.3-specific-binding by the HIRA histone chaperone complex. Nat. Commun 6, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneiderman JI, Orsi GA, Hughes KT, Loppin B, and Ahmad K (2012). Nucleosome-depleted chromatin gaps recruit assembly factors for the H3.3 histone variant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 19721–19726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ooi SL, Priess JR, and Henikoff S (2006). Histone H3.3 variant dynamics in the germline of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2, e97–e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakai A, Schwartz BE, Goldstein S, and Ahmad K (2009). Transcriptional and developmental functions of the H3.3 histone variant in Drosophila. Curr. Biol 19, 1816–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson EL, and Horvitz HR (1989). The multivulva phenotype of certain Caenorhabditis elegans mutants results from defects in two functionally redundant pathways. Genetics 123, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lakowski B, and Hekimi S (1996). Determination of Life-Span in Caenorhabditis elegans by Four Clock Genes. Science 272, 1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boycott AE, Diver C, Garstang SL, and Turner FM (1931). II. The inheritance of sinistrality in Limnæa peregra (Mollusca, Pulmonata). Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Contain. Pap. Biol. Character 219, 51–131. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moravec CE, Samuel J, Weng W, Wood IC, and Sirotkin HI (2016). Maternal Rest/Nrsf Regulates Zebrafish Behavior through snap25a/b. J. Neurosci 36, 9407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasson JA, Simon AK, Myrick DA, Wolf G, Driscoll S, Pfaff SL, Macfarlan TS, and Katz DJ (2016). Maternally provided LSD1/KDM1A enables the maternal-to-zygotic transition and prevents defects that manifest postnatally. eLife 5, e08848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szenker E, Lacoste N, and Almouzni G (2012). A Developmental Requirement for HIRA-Dependent H3.3 Deposition Revealed at Gastrulation in Xenopus. Cell Rep 1, 730–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong Q, Banaszynski LA, Geng F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Zhang H, O’Neill CL, Yan P, Liu Z, Shido K, et al. (2018). Histone variant H3.3-mediated chromatin remodeling is essential for paternal genome activation in mouse preimplantation embryos. J. Biol. Chem 293, 3829–3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue A, and Zhang Y (2014). Nucleosome assembly is required for nuclear pore complex assembly in mouse zygotes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 21, 609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elsässer SJ, Noh K-M, Diaz N, Allis CD, and Banaszynski LA (2015). Histone H3.3 is required for endogenous retroviral element silencing in embryonic stem cells. Nature 522, 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banaszynski LA, Wen D, Dewell S, Whitcomb SJ, Lin M, Diaz N, Elsässer SJ, Chapgier A, Goldberg AD, Canaani E, et al. (2013). Hira-dependent histone H3.3 deposition facilitates PRC2 recruitment at developmental loci in ES cells. Cell 155, 107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh KM, Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Stadler S, Dewell S, Law M, Guo X, Li X, et al. (2010). Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell 140, 678–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akiyama T, Suzuki O, Matsuda J, and Aoki F (2011). Dynamic replacement of histone H3 variants reprograms epigenetic marks in early mouse embryos. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002279–e1002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santenard A, Ziegler-Birling C, Koch M, Tora L, Bannister AJ, and Torres-Padilla M-E (2010). Heterochromatin formation in the mouse embryo requires critical residues of the histone variant H3.3. Nat. Cell Biol 12, 853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ng RK, and Gurdon JB (2007). Epigenetic memory of an active gene state depends on histone H3.3 incorporation into chromatin in the absence of transcription. Nat. Cell Biol 10, 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greer EL, Maures TJ, Ucar D, Hauswirth AG, Mancini E, Lim JP, Benayoun BA, Shi Y, and Brunet A (2011). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 479, 365–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lesch BJ, Tothova Z, Morgan EA, Liao Z, Bronson RT, Ebert BL, and Page DC (2019). Intergenerational epigenetic inheritance of cancer susceptibility in mammals. eLife 8, e39380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong A, Thorleifsson G, Frigge ML, Vilhjalmsson BJ, Young AI, Thorgeirsson TE, Benonisdottir S, Oddsson A, Halldorsson BV, Masson G, et al. (2018). The nature of nurture: Effects of parental genotypes. Science 359, 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Coghlan A, Ruan J, Coin LJ, Hériché J-K, Osmotherly L, Li R, Liu T, Zhang Z, Bolund L, et al. (2006). TreeFam: a curated database of phylogenetic trees of animal gene families. Nucleic Acids Res 34, D572—D580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edgley M, Baillie D, Riddle D, and Rose A (2006). Genetic Balancers. WormBook [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Iwase S, Xiang B, Ghosh S, Ren T, Lewis PW, Cochrane JC, Allis CD, Picketts DJ, Patel DJ, Li H, et al. (2011). ATRX ADD domain links an atypical histone methylation recognition mechanism to human mental-retardation syndrome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 18, 769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brenner S (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang D, Tu S, Stubna M, Wu WS, Huang WC, Weng Z, and Lee HC (2018). The piRNA targeting rules and the resistance to piRNA silencing in endogenous genes. Science 359, 587–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frøkjaer-Jensen C, Davis MW, Hopkins CE, Newman BJ, Thummel JM, Olesen S-P, Grunnet M, and Jorgensen EM (2008). Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Genet 40, 1375–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okkema PG, Harrison SW, Plunger V, Aryana A, and Fire A (1993). Sequence requirements for myosin gene expression and regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 135, 385–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahoney TR, Liu Q, Itoh T, Luo S, Hadwiger G, Vincent R, Wang Z-W, Fukuda M, and Nonet ML (2006). Regulation of synaptic transmission by RAB-3 and RAB-27 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2617–2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allman E, Johnson D, and Nehrke K (2009). Loss of the apical V-ATPase a-subunit VHA-6 prevents acidification of the intestinal lumen during a rhythmic behavior in C. elegans. AJP Cell Physiol. 297, C1071–C1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kennedy BP, Aamodt EJ, Allen FL, Chung MA, Heschl MFP, and McGhee JD (1993). The Gut Esterase Gene (ges-1) From the Nematodes Caenorhabditis elegans and Caenorhabditis briggsae. J. Mol. Biol 229, 890–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis MW, Hammarlund M, Harrach T, Hullett P, Olsen S, and Jorgensen EM (2005). Rapid single nucleotide polymorphism mapping in C. elegans. BMC Genomics 6, 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhatla N, Droste R, Sando SR, Huang A, and Horvitz HR (2015). Distinct neural circuits control rhythm inhibition and spitting by the myogenic pharynx of C. elegans. Curr. Biol 25, 2075–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, and Salzberg SL (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25–R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li B, and Dewey CN (2011). RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, and Subgroup, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl 25, 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anders S, and Huber W (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106–R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S2. C. elegans strains used in this study. Related to STAR methods. The C. elegans strains used in this study.

Table S1. Gene expression changes in hira-1 mutants. Related to Figure 4. Genes that change expression in hira-1(-) compared to wild-type animals at the indicated stages. UP, indicates genes up-regulated (at least 2-fold, P<0.01); DOWN, indicates genes down-regulated (at least 2-fold, P<0.01). The log2 fold change and p-values are listed for each gene. The genes in this table correspond to the red and blue areas of the pie-charts and Venn diagrams in Figure 4.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data are available at the GEO: GSE144686