Abstract

Objectives

From 2016 to 2018 Florida documented 1471 cases of Zika virus, 299 of which were pregnant women (Florida Department of Health, https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-bornediseases/surveillance.html, 2019a). Florida’s response required unprecedented rapid and continuous cross-sector communication, adaptation, and coordination. Zika tested public health systems in new ways, particularly for maternal child health populations. The systems are now being challenged again, as the Coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic spreads throughout Florida. This qualitative journey mapping evaluation of Florida’s response focused on care for pregnant women and families with infants exposed to Zika virus.

Methods

Fifteen focus groups and interviews were conducted with 33 public health and healthcare workers who managed outbreak response, case investigations, and patient care in south Florida. Data were thematically analyzed, and the results were framed by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Healthcare Systems Framework of six building blocks: health service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, financing, and leadership and governance (World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf, 2007, https://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/monitoring/en/, 2010).

Results

Results highlighted coordination of resources, essential services and treatment, data collection, communication among public health and healthcare systems, and dissemination of information. Community education, testing accuracy and turnaround time, financing, and continuity of health services were areas of need, and there was room for improvement in all indicator areas.

Conclusions

The WHO Framework encapsulated important infrastructure and process factors relevant to the Florida Zika response as well as future epidemics. In this context, similarities, differences, and implications for the Coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic response are discussed.

Keywords: Zika virus, Coronavirus, COVID-19, Miami-dade county, Florida, Health systems framework, Pregnancy

Significance

During infectious disease outbreaks, public health systems work in concert with multiple national, state, and local health, communication, and environmental systems to prevent spread and to mitigate morbidity and mortality. Much was learned from the 2015 Zika pandemic. These lessons should be applied to address the much larger COVID-19 pandemic. The WHO Building Blocks of Health Systems provides a framework for planning, action, and evaluation.

Introduction

Zika virus is a vector-borne disease transmitted by mosquito bites from the species Aedeas Aegypti, contact to bodily fluids such as during sex, or congenitally from mother to fetus. Zika exposure during pregnancy can result in fetal loss or a range of birth defects from microcephaly to less apparent sequelae such as hearing loss or speech delay (Rasmussen, et al. 2016; Rice et al. 2018). Zika infection is also known to be associated with Guillain- Barré Syndrome in adults, resulting in long-term neurological symptoms (Mlakar et al. 2016a, b; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018; Krauer et al. 2017). It is estimated that only 20% of individuals infected with Zika experience symptoms. Among symptomatic patients, symptoms such as mild fever, rash, headache, joint pain, conjunctivitis and muscle pain are most common (CDC 2018).

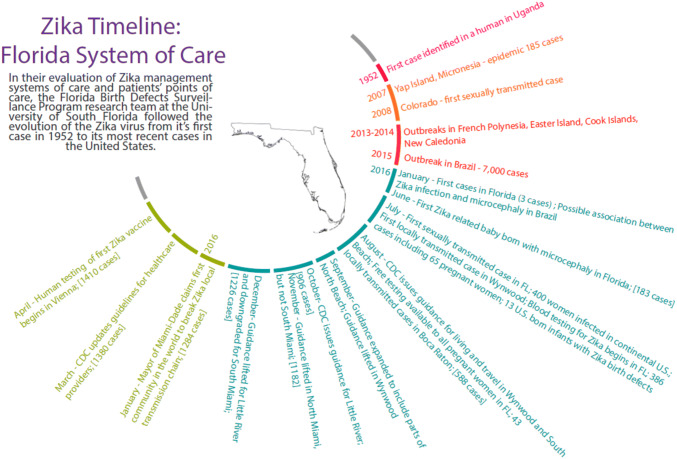

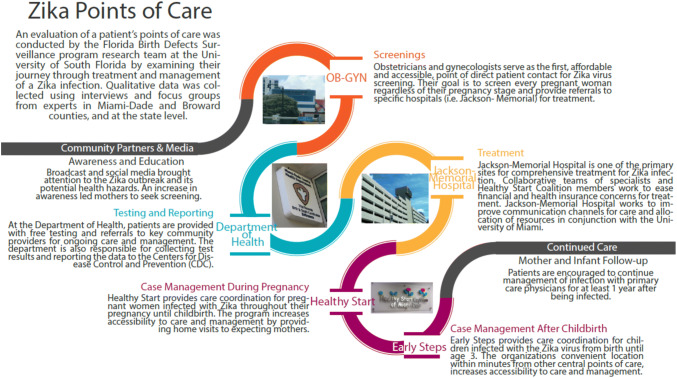

In 2015, the first cases of Zika were identified in the Americas, including the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, and by 2016 the U.S. Virgin Islands and the states of Texas and Florida had identified cases of Zika that were infected through mosquito-borne transmission. During this time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released guidelines for testing symptomatic patients and pregnant women regardless of symptoms, recommendations for avoiding mosquito bites and sexual transmission, and urged pregnant women to postpone travel to areas of active transmission by mosquitos (Petersen et al. 2016; Oster et al. 2016; Staples et al. 2016). On July 29, 2016, Florida announced that the first locally-acquired cases of Zika via mosquito transmission had been identified in Broward and Miami-Dade Counties. Due to local Zika transmission, the CDC declared Miami, Florida the first and only cautionary travel location in the continental U.S. on August 1, 2016 (CDC 2016). A timeline of events is illustrated in Fig. 1. Throughout 2016, Florida had 218 locally-acquired Zika cases via mosquito transmission, more than any other state (CDC 2019). Florida’s efforts to respond to the local Zika outbreak was a collaboration of multiple agencies (examples displayed in Fig. 2) and included state-sponsored testing for any pregnant woman beginning August 3, 2016. The magnitude of the Zika outbreak in Florida and unique scale of public health and healthcare response prompted this evaluation of Florida. Leveraging the six building blocks of the WHO Health Systems Framework (2007, 2010), the purpose of this evaluation was to assess the cross-sector collaboration and adaptations among systems of care in Florida during the Zika outbreak in order provide recommendations for response to future outbreaks. The framework was chosen to guide analysis after data had been collected because of its applicability and adaptability to various contexts.

Fig. 1.

Zika outbreak timeline

Fig. 2.

Zika health sevices points of care

The WHO Health System Framework provides a structure for describing the multifaceted response of Florida’s health system to locally-acquired Zika. This framework embodies the needs of a health care system and has been used to evaluate the strengths and challenges as well as assess the benefit of changes to healthcare systems across the world (Chakravarty et al. 2015; Howard et al. 2014; Roshan et al. 2018; Sayinzoga and Bijlmakers 2016; Acharya et al. 2017; Appiah et al. 2018; Helena 2016; Manyazewal 2017). Though some suggest that there are limitations in using WHO building blocks for analyzing dynamic, complex and inter-linked system impacts (Mounier-Jack et al. 2014), this broad framework was suitable for guiding analysis specific to infectious disease outbreak response, with modifications to evaluate how patients are connected with care and the quality of service at the community level (Sacks et al. 2019).

Each of the WHO’s six building blocks (service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, financing, and leadership/governance) is vital to meeting the needs of a population, with specific considerations during epidemics or other disasters (Sacks et al. 2019; Manyazewal 2017; WHO 2010). The health service delivery component focuses on evaluating access to health care delivered efficiently to those who need it. Health workforce measures whether the available resources of a system adequately respond to health care needs. Health information systems involve the timeliness, accuracy, and use of health facility data, individual level patient data for clinical and system decision-making, and population level data, surveillance, and education. Sufficient access to essential medicines and medical equipment (products, vaccines, technologies) is also evaluated. Lastly, the financial stability of a health care system and whether the leadership/governance has created policies for a suitable health care and adequate public health emergency response is measured (WHO 2010). These building blocks are interconnected such that without any one block, health care systems will fail to provide suitable care for the population. As in the case of Zika in the U.S., the current state of COVID-19 highlights the demand for these principles in a comprehensive system of response. Less than four years later, we are experiencing a pandemic of monumental proportions. As of June 23, 2020 the U.S. has identified 1.9 million cases of novel coronavirus (COVID-19), including 100,217 in Florida with 3173 deaths (Florida Department of Health 2020). It is an unprecedented outbreak leading to response efforts rapidly adjusting to an event that is seemingly changing daily. The CDC reported that older individuals and those with pre-existing medical conditions are at a greater risk of complications and that it may be difficult for an individual to be tested for COVD-19 (CDC 2020a). Significant findings from the evaluation of Florida’s response to the Zika outbreak parallel the challenges that the U.S. response to COVID-19 is currently encountering; establishing government-sponsored laboratory testing, maintaining accurate messaging to the public based on the most current research, and establishing recommendations for those that are most vulnerable. As such, results from this evaluation helped us to understand Florida’s Zika response so that insights could be useful in managing future disasters, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Florida’s response to the Zika public health emergency was evaluated using a descriptive qualitative case study design, which aims to describe an event, case, or phenomena of interest in its authentic context by utilizing reports, observations, and interviews (Yin 2003). A journey mapping (Cruickshank 2009; Johnston and Kong 2011; Zomerdijk and Voss 2010) approach was used; the evaluation team follow Florida’s process maps (FDOH 2019a, b) for serving pregnant women and infants affected by Zika virus, and conducted semi-structured interviews and focus groups with agency staff at each step. The evaluation team consisted of the principal investigator (PI) who has a PhD in public health, two other public health faculty, and bilingual graduate students trained and experienced in community-based qualitative research. The team wa diverse in terms of gender, nationality, race and ethnicity, and training (community health, epidemiology, medicine, and infectious disease).

We used purposive and snowball sampling to recruit participants via email who met the inclusion criteria as a current employee of their respective agency and with an active role in the care of Zika-positive patients or Zika outbreak management in Florida (Table 1). The PI was known to several of the participating agencies, though not specifically with interviewed staff. Prior to conducting interviews or focus groups, participants were informed of the goal of the evaluation, that their participation was voluntary, and gave verbal consent to participate in a single conversation up to 90 min.

Table 1.

Participating agencies

| Participating Agencies: Florida’s Zika Response System of Care |

|---|

| Hospital: Pediatrics, Obstetrics |

| Local Obstetrics Clinic |

| Federally Qualified Health Center |

| Reproductive Health Center (Planned Parenthood) |

| Maternal and Child Health (Healthy Start) |

| Early Steps Pediatric Intervention Program |

| Birth Defects Surveillance Program |

| Vector Borne Diseases Surveillance Program |

| Zika Pregnancy Registry Surveillance Program |

| Department of Health: Epidemiology, Infectious Disease |

| Department of Health: County |

| Mosquito Control |

| University: Infectious Disease Research |

The PI recruited participants by contacting representatives of agencies involved in the response, including agencies listed on Florida Department of Health (FDOH 2019b) process maps and others in the community who work with maternal and child populations. Semi-structured interviews and focus group participants were conducted in-person or by phone. Participants were asked to describe: the system of referrals and services for Zika-affected mothers and infants in the community or state (key partners/agencies, what happens when a pregnant woman or a newborn is identified with Zika infection); how well they feel the system is working; and challenges/gaps, strengths. and recommendations for system improvement. To protect the anonymity of participants, no personal identifiers were collected. The purpose of the evaluation (to understand and evaluate the systems of care response to the Zika epidemic), the interviewer’s role as an outside evaluator (not an employee or representative of the Department of Health), and assurance of confidentiality were reiterated prior to each interview or focus group. Discussions were audio recorded, professionally transcribed verbatim, and reviewed for accuracy. Detailed notes were taken for interviews with one public health agency who requested to not be recorded; a debrief of the notes was audio recorded and transcribed, then coded along with direct audio transcripts. The evaluation team determined that saturation was reached when all identified stakeholders/services sectors were interviewed and themes were repeated (no new themes emerged).

Verbatim transcripts were reviewed with audio files for accuracy. Following an initial read-through of the transcripts, the evaluation team determined that an overarching framework (beyond challenges, strengths, and recommendations) would facilitate coding and interpretation. The WHO framework was most aligned with the themes that emerged from data collected. Therefore, a codebook, which included a hybrid of a priori and emergent codes, was developed and tested on one transcript. Two trained research assistants conducted coding to establish agreement, then coded the remaining transcripts independently. MAXQDA software (VERBI Software 2017) was used to review and categorize the transcripts according to the six building blocks of the modified framework. Transcripts were analyzed for themes matching the WHO Health System Framework for principles. As with previous studies using this framework, the definition of each building block was modified to appropriately evaluate Florida’s system of response to Zika (Mounier-Jack et al. 2014). Results were shared with community stakeholders via webinar and in the form of a final report. Further review of the results identified how challenges/gaps, strengths, and recommendations observed in the evaluation of Florida’s response to Zika can be applied to the COVID-19 outbreak response.

Results

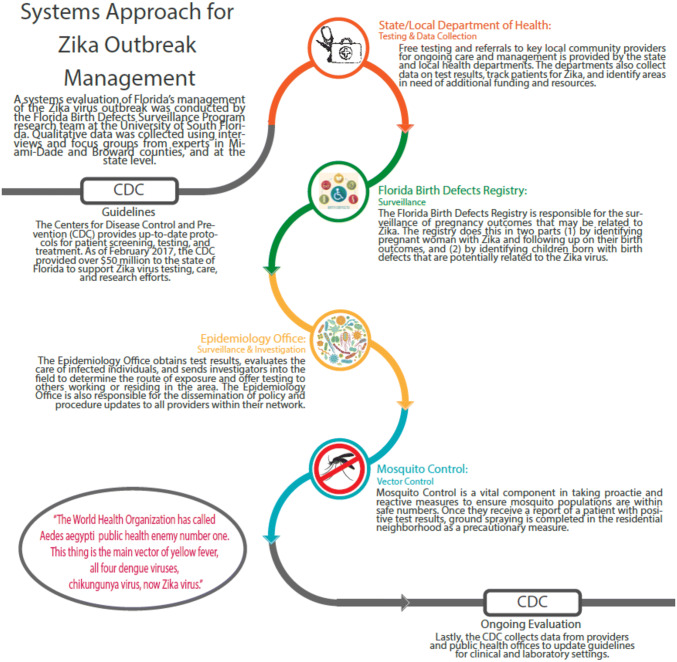

Participants in 15 focus groups and interviews consisted of 33 physicians, nurses, project coordinators, program directors, professors, epidemiologists, researchers, case managers, care coordinators, and professionals from various point of care and outbreak management systems in Florida (Table 1). The building blocks were clearly reflected in participant comments (Table 2) as shown in the system journey map. The evaluation of Florida’s Zika response, in alignment with WHO’s six building blocks for an effective response during an epidemic, is presented below. The results emphasized the cross-sector, multi-level collaboration and communication that occurs during a dynamic and rapidly evolving crisis, such as the Zika epidemic (Fig. 3). System challenges, strengths, and recommendations, as well as insights into the COVID-19 response are also discussed.

Table 2.

Zika response building blocks and quotes

| Building block | Quote |

|---|---|

| Health service delivery, Health Care and Testing | “At [the hospital], the way that it works now is that a woman is seen in the OB clinic, ‘Hello. How are you? You’re pregnant,’ and we have a separate phlebotomist downstairs in the outpatient lab where the pregnant woman doesn’t have to wait for her Zika testing so she finishes her clinical visit. She goes down a floor. She has her blood and urine collected and then she goes.”—Health Care |

| Health service delivery, Health Care | “Right now, under Early Steps, a child has to be Zika positive in order to be eligible for Early Steps or have [a neurological] disability like be born to a mother with Zika positivity and be microcephaly or have intracranial calcification or something else but they have to have one of those two things.”—Health Care |

| Health service delivery, Health Care | “A lot of these women don’t look to seek the care after birth because they think their babies are fine even if there is still a probability that something may happen down the line… they moved back to their country so we can’t really track them down there… other states in the US, or territories like Puerto Rico or Virgin Islands.”—Public Health |

| Health service delivery, Coordination | “… Once the tests are positive, then we try to see whether or not the pregnant woman has a provider on file so we can follow up with the provider…, or if they don’t have a provider, then we just go over what the results – what test came back positive. Try to explain what’s going on with the whole process and then if they don’t [have a health care provider], we tell them about Healthy Start. Then after that, we are the ones that refer the pregnant women…”—Public Health |

| Health Service Delivery, Testing | If they’re lucky that in an epidemic that had lasted more than, I don’t know, six months. To think that’s 18,000 pregnancies that should have been tested.”—Care Coordination |

| Health workforce, Training | “[Community Health Center] is another relatively low-budget access clinic…and they’ve been contacting me directly… if it’s an uninsured patient then we’ll deal with everything there. So, they’ve been probably my second greatest source of referrals from the community.”—Health Care |

| Health workforce, Training | “So we’re hoping some of that state… information money gets used [towards]… Educating providers, both pediatricians and obstetricians, and nurse practitioners.”—Health Care |

| Health workforce, Capacity | “They [CDC] have a local county health department initiative right now that they’re providing to have a CDC contractor go to the local county health department and are involved in whatever aspect of Zika that you’re interested in. We have different groups, and everyone picked outreach so we have funding.”—Surveillance |

| Health workforce, Training | “They’re [obstetricians] usually not fully aware of what the pediatric resources are at their hospital but the CDC recommends early access to pediatric infectious disease, pediatric audiology, pediatric neurology and head imaging of the infant. So, if they’re in a hospital where he or she is unsure if they can do an ultrasound and MRI of the baby before they’re discharged, the goal is to do all of this screening before discharge—because it’s been pretty obvious that if you just give the mom five different clinic appointments they’re just not going to go. It’s too much.”—Health Care |

| Health workforce, Training | “Because the main thing, when our fellows call them on the phone, ‘Please come back,’ they’re like, ‘My baby looks fine.’ Then they’ll say, ‘Well, I went to the pediatrician and the pediatrician also told me he looks fine or she looks fine.’ …we need to start reaching out to the pediatricians and start educating them that even though the baby looks fine and everything looks okay so far, they have to bring them back.”—Health Care |

| Health workforce, Training | “I’ve been going through every single provider’s office in [the County] and the toolkit that we give them has the algorithm for testing, when to test, and then what the test results mean and how to read the test results.”—Public Health |

| Health information systems, Infectious Disease Response | “…every time that they [FDOH Epidemiology Office] receive any patient from the doctors or the clinics or the hospital they know about, then immediately after, we will know about it. They will report it to us so we’d take the right mosquito control measure in the areas where these cases are.”—Mosquito Control |

| Health information systems, Public Education and Outreach | “They provided and continue to provide a kit that we hand to our mothers that has a repellent either lotion or cream. They also have the pamphlet where they get information about training and coverage, putting the long sleeves, using the condom. We also included in the bag, condoms. It’s a great teaching opportunity. We would hand them the bag with all these provisional things that really reiterated the message of protecting themselves while they were expecting in all those areas.”—Care Coordination |

| Health information systems, Public Education and Outreach | “The majority of the supplies that we’ve provided and will remain providing had been from the coalition. The Zika kits, probably 100 and we served well over a thousand women in – I’m sure more—in the last six, seven months so they had been providing us with like I said a household repellent. It has condoms. It’s a diaper bag. It also has the education for the Department of Health… and CDC guidelines, ‘This is what you need to do. You need to cover yourself. Use condoms,’ et cetera.”—Care Coordination |

| Health information systems, Public Education and Outreach | “Honestly, I think the [Healthy Start] coalition has really done a lot of the heavy-lifting like I said, providing resources for us to be available at the clinic…They also order and provided us [with] the resources for the repellents and other items. They also were the liaison between the Department of Health and us because we needed directions.”—Care Coordination |

| Health information systems, Public Education and Outreach | “In addition to that [distributing Zika kits], we had outreach in our health centers with the information sheet… We were giving those out at our health centers, and we were also distributing Zika kits to women that were our patients who came in and said they were going to continue their pregnancy.”—Health Care |

| Health information systems, Public Education and Outreach | “I feel like the tourists are probably getting the best messaging but trying to reach out to those other groups are a bit harder which is why it’s important to know where they are in your county so that you can try to [be targeting on] messaging whether or not it’s through like Spanish radio or Asian or Creole radio… We have to involve them [the Media] in anything really that’s going out to the public because they have the best way to do the messaging or the best way to get people’s attention.”—Public Health |

| Health information systems, Surveillance | “You have to consider there are two kinds of moving parts to this… They’re the Zika pregnancy registry, which is focused more on identifying pregnant women who have Zika and then following up on their birth outcomes, which is more the prospective approach. Then you have the retrospective approach, identifying children born with birth defects that are potentially related to Zika virus, they’re collecting information on them.”—Birth Defects Surveillance |

| Health information systems, Infectious Disease Response | "Their networks are these 700 providers as well as the APIC System [Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology]. These groups are responsible for communication about all infectious disease including West Nile virus, Ebola, SARS, H1N1, and ZIKA is the same process. They receive their information from the state department and CDC. They send a blast fax to all their providers… This information is distributed to all doctors and their network…about 700 providers. They are at each of the hospitals—Jackson Memorial and UMH [University of Miami Hospital]." -Public Health (debrief) |

| Health information systems, Infectious Disease Response | “In terms of communication about ZIKA, this agency communicates the results they receive from CDC, the MMWR and the Department of Health through their network of providers.”—Public Health (debrief) |

| Access to essential medicines: products, vaccines and technologies | “Let’s say we do have a Zika vaccine. Who are you going to give it to? Everybody? Who’s going to pay for that? If you do have a vaccine and you use it as a true tool in an integrated program, you not only use ‘Where is the virus?’ which you can find out from the mosquitoes if you have good surveillance, and then you alert that neighborhood or that area.. ‘Go to the Public Health. Get a vaccine.”—Infectious Disease Research |

| Access to essential medicines: products, vaccines and technologies | The other thing of course is—that we need resources for—I don’t know how we can cut research when we’re dealing with a disease that for me is worse than HIV. Because with HIV, if mother is HIV positive, we have antiviral drugs. We can say, ‘Okay you can take these antivirals, and the possibility of transmission to your baby it can reduce to almost zero.’ If a mother has a Zika virus, nothing. No antivirals.”—Infectious Disease Research |

| Access to essential medicines: products, vaccines and technologies | “We look at the trap data in those areas and we see the average of mosquitoes caught on a weekly basis increases, but they trap more than—between five and ten, we go back and looked around to see where are these mosquitoes are coming from, but at this point, we are trying to be a little bit more proactive, so we’re still spraying larvicide by ground, by truck on a weekly basis.”—Mosquito Control |

| Health systems financing | “Because in the State of Florida this governor announced that the state will eat the cost of all of this Zika testing for pregnant women and that we could not afford to do any of this without that declaration like we would’ve been [unable to test] last summer if it wasn’t for that declaration.”—Health Care |

| Health systems financing | “But then the question I have for you is who’s going to get it? How are you going to vaccinate the entire population of Florida to prevent five microencephalic babies a year? Who’s going to pay for that?”—Infectious Disease Research |

| Health systems financing | “About half of the $13 million given to us by the Department of Health were for longitudinal neonatal studies so essentially enrolling the mom while she’s still pregnant or shortly after childbirth, for three years of continuity of care for the infant with compensation for travel and time and neurocognitive development, neuro imaging, neurology, ear, nose and throat—so basically above and beyond what the CDC is recommending for three years in both an investigation capacity and recognition that most patients can’t afford all of this.”—Health Care |

| Health systems financing | “And the state just got a big grant to do essentially coordination of services…Yes, $2.3 million for three years and they are supposed to be doing coordination…They want to build like a resource center so that, let’s say, in the practical world, South Miami or Mercy Hospital or Baptist has a case and they would contact this resource center who would direct it to the Zika response team for peds [pediatrics].”—Health Care |

| Health systems financing | “If they want to give us $3 million a year, which is about what we should have in our program, then we could do all these things wonderfully.”—Surveillance |

| Leadership and Governance | “CDC has put together guidelines and recommendations and what conditions are related to Zika…There’s specific codes, again, that are related to those conditions. Like microcephaly, there’s a code for microcephaly”.—Surveillance |

| Leadership and Governance | “Department of Health, speaking on both formally and informally referring pretty much every positive woman to me, sometimes for my care…they would have me explain the testing or at least give my perspective even if they stayed in my community.”—Public Health |

| Leadership and Governance | “I always say, ‘We have to protect Florida.’ Why? Because we have the same situation… of a lot of travelers, tourists.” – Infectious Disease Research |

Fig. 3.

Zika response system map

WHO’s Six Building Blocks

Service Delivery

Service delivery was facilitated by collaboration among local agencies and supported by strong federal, state and local coordination (examples illustrated in Fig. 2). For example, the CDC and agencies in the FDOH leveraged existing disease surveillance systems to manage outbreak investigations and establish a registry of Zika-positive pregnant women. This registry was utilized to share information with health care providers and case managers to confirm that they had been connected with access to care. Additionally, prenatal and pediatric health care providers worked together, and reported cases to FDOH’s Bureau of Epidemiology. Locations with evidence of local transmission from mosquitos were reported to the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services and local districts within the Florida Coordinating Council on Mosquito Control to reduce mosquito breeding.

Health Workforce

Patient referrals were noted to be advantageous within the community-embedded, competent health workforce (case managers, perinatal home visitors, health care, and social services providers). Experts (e.g., Zika care team at the hospital) made themselves available to their colleagues for consultation. Interagency communication was essential in reducing duplicative patient outreach and disseminating new guidance and program protocols. Those in the workforce at the forefront of Zika response were trained, knowledgeable, and in many cases bilingual or trilingual to meet the needs of Spanish- and Creole-speaking families in the Miami-Dade area.

Health Information System

The health information system relied on Bureau of Epidemiology outbreak response staff who provided updates to health care providers as new guidance was continuously modified by the CDC (Fig. 3). Further, disease investigations systems already being used by the Bureau of Epidemiology and data collection in place at the Florida Birth Defects Registry at the time of the outbreak quickly created surveillance and adapted protocols and provided updates on the numbers of identified cases. Public information systems also encompass health education to the community at large, which relies on partnerships among experts, public health agencies, social services and the media.

Essential Services

Access to some essential services such as testing, care and follow-up was facilitated by state agencies. State-funded laboratory testing was made available to pregnant women, health care providers, and case managers. Home visiting, social services, care coordination, and healthcare providers were able to support women and families, regardless of income. Early intervention services eligibility criteria was expanded for infants affected by the virus. There were hopes that a vaccine for Zika virus could be developed, though this did not come to fruition.

Funding

Funding at the state level provided for testing pregnant women, additional outbreak management staff and case managers, an educational campaign by the FDOH, and longitudinal research at a major hospital in Miami-Dade County. Financial barriers to care were also leveraged by engaging existing safety net programs, such as Healthy Start Coalitions and health departments.

Leadership and Governance

All of these efforts were supported financially and administratively through Leadership and governance, which acted quickly at the federal, state, and local levels in partnership to provide information and support, public education, Zika prevention supply kits, disease surveillance, specialized health care and testing.

Challenges, Strengths, and Recommendations

Among the reported gaps was a lack of investment in a vaccine and numerous concerns regarding the accuracy and timing of laboratory testing. Participants noted questions, concerns, and ethical dilemmas related to pregnant women receiving false positive results, determining when to get tested, and the issue of confirmatory testing taking several weeks as the pregnancy progressed, thereby limiting options for follow-up care decisions. Other reported gaps included reliance on symptomatic Zika-positive patients seeking health care and for health care providers to order appropriate laboratory testing to identify index cases in areas where local transmission might not have been identified. Another challenge was the high cost for testing male or non-pregnant patients (particularly as the virus is also sexually transmitted). Additionally, it was suggested that timing of laboratory results should be shortened and that a system of care for Zika-positive patients should be created that is similar to HIV-positive patients. Other barriers included difficulty in identifying the source or location of exposure in some patients, and a lack of public awareness of the range of congenital abnormalities caused by Zika exposure. In fact, the parents of many infants identified with Zika at birth did not return for follow-up care, even though it was known that health effects were likely to appear later in infancy or childhood.

The CDC was a cornerstone of Zika response by frequently updating guidance as research developed and quickly communicated those changes in a clear and systematic manner. This pipeline of reliable communication from the federal level to individual health care providers and patients was noted to be essential. It facilitated state and local decision-making to prioritize resources and efforts during the Zika response and should be utilized during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Further recommendations were to increase mosquito control efforts to reduce the risk of exposure; this includes continuing to encourage public support of actively minimizing the presence of standing water to reduce mosquito breeding sites. It was also suggested that mosquito breeding grounds be better understood to reduce the risk of disease.

Insights into COVID-19 Response

Lessons learned from Zika include the importance of coordination across sectors and levels, resilience at the local level, an effective testing strategy, policy and funding to support all levels of prevention and treatment, and effective risk communication. While cross-level coordination and communication, united messaging, and testing strategies seem to have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, local response in Florida was strong. Many agencies continue to provide uninterrupted services through telehealth and community-based efforts, from COVID-19 prevention messaging, to social services, and local food distribution centers to offset the impacts of school closures and widespread unemployment. The state and local health departments and community agencies have a history of working together. Additionally, local and state jurisdictions put policies in place—some faster than others—to prevent the spread of the virus. Agencies still look to the CDC and WHO for guidance.

As mentioned by Mounier-Jack et al. (2014), the coordination of activities by the health workforce can improve the health outcomes of the population. Cross-sector collaboration in Florida was evident when response efforts resulted in timely laboratory testing, surveillance, and dissemination of guidance, and coordinate patient care, as noted by evaluation participants. These strengths of Florida’s Zika response should be echoed in the COVD-19 response. Florida has seen exponentially more COVID-19 confirmed cases than of combined locally-acquired and travel-acquired Zika cases in 2016. Both Zika and COVID-19 spread rapidly across international borders. On March 16, 2020 the CDC issued a warning for all global travel, illustrating that this large scale pandemic requires equally greater response (CDC 2020b). Specifically, this evaluation emphasized the value of collaboration, coordination, and communication across federal, state, and local levels as well as among agencies within each level. Unfortunately, collaboration across levels has been stilted throughout COVID-19; policy and messaging have not been consistent across states, or even within states.

Community resilience is enhanced by strong social ties and networks. Leveraging these communication and partner networks facilitated rapid implementation under complex dynamic conditions. Certainly messaging impacts risk perceptions; as one public health professional explained in the case of Zika, “I think a lot of people realize ‘mosquito, mosquito, mosquito’ but they’re not necessarily thinking of these others – or they’re thinking, ‘I’m not pregnant. Why does it matter to me?’” This point was also made by another practitioner, “Lessons have been learned in terms of HIV or hepatitis that if the messaging is not targeted to people who are married, who have higher income, they don’t believe they’re at risk, it’s a missed opportunity.” Various policies of quarantine and community-wide isolation are being enforced across the U.S. and the state as a measure to prevent the spread of COVD-19, emphasizing the crucial roles of state and at the local level leadership in creating, communicating, and enforcing policy, and the federal level for creating and disseminating research-based guidance. During COVID-19, CDC was not supported as the cornerstone of information and we have not seen the “pipeline of reliable communication from the federal level to individual health care providers and patients” observed in the Zika response, which is crucial for facilitating state and local decision making. Public risk perceptions have also been inconsistent, as the impacts of COVID-19 on vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women, infants/children, and others with underlying health conditions is still largely unknown. Similar to Zika, the perceptions of risk are low as majority of cases are asymptomatic; COVID19 has also been largely communicated as a risk only to elderly populations. To add to the complexity of the situation, COVID-19 prevention messaging has been subsumed within political messaging, conflating the two in the minds of some segments of the population.

In relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, conducting effective and efficient large-scale testing has been one of the main challenges of the response to this current outbreak (Shah et al. 2020). Florida’s policy to offer state-sponsored laboratory testing for pregnant women shortly after the first locally-acquired Zika case was applauded. While Zika testing fell short in terms of meeting the need for testing among other populations, this focus on pregnant women raised awareness, improved access to services, and facilitated disease surveillance. Further, the evaluation found that direct access to health care providers and case managers who were knowledgeable about Zika benefited patients. This access was made possible through a well-established referral network and communication among community and maternal child health services providers to reduce the burden on the patient.

COVID-19 affects the entire population, and amplifies risks and impacts on vulnerable populations. While rapid and accurate testing is still not readily available, case management and home visiting services (now offered virtually) and health care without cost barriers have the potential to similarly improve the COVID-19 response for women, children and families. Our health information systems for Zika relied on contact tracing and adaptation of protocols based on the number of cases. The number of cases of COVID-19 in Florida grew from 1 to over 100,000 in the span of just four months (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center 2020). The need for health care is rising and the long term health effects are still largely unknown. Continued clinical research and epidemiologic surveillance will inform further public health response. Continuous and rapid adaptations to new information rely on a well-informed policy makers and leaders.

At the time of the evaluation, a tropical disease researcher noted that research for a Zika vaccine could be available in the future. A vaccine for Zika was never made available to the public, which was seen as a limitation of the response. Currently there is a global effort to develop vaccines for SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, however this will take time and significant investment (Chen et al. 2020). Some recommendations during the evaluation of Florida’s response to the local Zika outbreak was to reduce turnaround time for laboratory testing, encourage public education, and public support for prevention efforts. These efforts have clear benefits to helping any response to a biological disaster. Encouraging public education efforts and providing useful prevention tasks that use public participation has the potential to benefit given the more encompassing effect of COVID-19. Additionally, funding for research, equipment, testing, and economic relief have been provided for COVID-19 response, though as in the case of Zika, the mechanisms for releasing adequate funds efficiently and quickly to all who need it remain a challenge.

Conclusions

Florida’s response to an outbreak of locally-acquired Zika showed strengths in making laboratory testing, health care, case management, an educational campaign, and frequently new guidance rapidly available. However, length of time for test results, lack of vaccine development, testing requirements for non-pregnant women, lack of public knowledge about sexual transmission, and many birth abnormalities associated with Zika were seen as setbacks. Recommendations included encouraging public support for prevention measures, increased knowledge about transmission, availability of testing and reduced turnaround time for laboratory results to reach patients. Unfortunately, although local and state agencies are now more experienced in these processes, the rapid exponential spread of the COVID-19 virus and confusion at the federal level have stymied improvements in these areas.

The purpose of this evaluation was to provide feedback of Florida’s response to the Zika outbreak to stakeholders. Parallels can be seen between the two pandemics in terms of a rapidly evolving situation, a need for testing and disease surveillance, concerns about health care, and a desire for a vaccine. The reports gathered from responders to the Zika outbreak in this evaluation led to informative lessons learned that can be applied to support the current response to COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by an award from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (CDCNBDDD), Cooperative Agreement CDC-RFA-DD10-100104CONT13. The content presented in this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- WHO

World Health Organization

- FDOH

Florida Department of Health

- COVID-19

Novel Coronavirus

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Appiah B, Amponsah IK, Poudyal A, Mensah MLK. Identifying strengths and weaknesses of the integration of biomedical and herbal medicine units in Ghana using the WHO Health Systems Framework: A qualitative study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2334-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya B, Ekstrand M, Rimal P, Ali MK, Swar S, Srinivasan K, et al. Collaborative care for mental health in low- and middle-income countries: A WHO health systems framework assessment of three programs. Psychiatric Services. 2017;68(9):870–872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). CDC issues travel guidance related to Miami neighborhood with active Zika spread. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0801-zika-travel-guidance.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Zika virus health effects & risks. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/zika/healtheffects/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). 2016 Case Counts in the US. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/zika/reporting/2016-case-counts.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/high-risk-complications.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Travelers’ Health – Global COVID-19 Pandemic Notice. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/warning/coronavirus-global.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (n.d.). Zika Symptoms page. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/zika/symptoms/symptoms.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (n.d.). Zika Testing page. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/zika/symptoms/diagnosis.html and https://www.cdc.gov/zika/hc-providers/testing-for-zika-virus.html.

- Chakravarty N, Sadhu G, Bhattacharjee S, Nallala S. Mapping private-public-partnership in health organizations: India experience. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health. 2015;5(2):128. doi: 10.4103/2230-8598.153811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Strych U, Hotez PJ, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine pipeline: An overview. Current Tropical Medicine Reports. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40475-020-00201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunkilton DD. Staff and client perspectives on the journey mapping online evaluation tool in a drug court program. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2009;32(2):119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Health. (2019a). Mosquito-Borne Disease Surveillance. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-borne-diseases/surveillance.html.

- Florida Department of Health. (2019b). Zika Process Maps. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://fcaap.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/FDOH-Zika-Process-Maps-.pdf.

- Florida Department of Health. (2020). Florida’s COVID-19 Data and Surveillance Dashboard. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/96dd742462124fa0b38ddedb9b25e429.

- Helena R. Cross-border healthcare directive: Assessing stakeholder’s perspectives in Poland and Portugal. Science Direct. Health Policy. 2016;120:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard N, Woodward A, Patel D, Shafi A, Oddy L, ter Veen A, et al. Perspectives on reproductive healthcare delivered through a basic package of health services in Afghanistan: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. (2020). COVID-19 United States Cases by County. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map.

- Johnston R, Kong X. The customer experience: A road-map for improvement. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal. 2011;21(1):5–24. doi: 10.1108/09604521111100225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krauer F, Riesen M, Reveiz L, Oladapo OT, Martínez-Vega R, Porgo TV, et al. Zika virus infection as a cause of congenital brain abnormalities and Guillain-Barré syndrome: Systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 2017;14(1):e1002203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manyazewal T. Using the World Health Organization health system building blocks through survey of healthcare professionals to determine the performance of public healthcare facilities. Archives of Public Health. 2017;75(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13690-017-0221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popovic M, et al. Zika virus associated with microcephaly. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:951–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popović M, Poljšak-Prijatelj M, Mraz J, et al. Zika virus associated with microcephaly. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(10):951–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier-Jack S, Griffiths UK, Closser S, Burchett H, Marchal B. Measuring the health systems impact of disease control programmes: A critical reflection on the WHO building blocks framework. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):278–285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster AM, Brooks JT, Stryker J, Kachur RE, Mead P, Pesik NT, Petersen LR. Interim guidelines for prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65(5):120–121. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6505e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman D, Fischer M, Ellington SR, Callaghan SM, Jamieson DJ. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65(2):30–33. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6502e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. Zika virus and birth defects—reviewing the evidence for causality. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:1981–1987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Galang RR, Roth NM, et al. Vital signs: Zika-associated birth defects and neurodevelopmental abnormalities possibly associated with congenital Zika virus infection—U.S. territories and freely associated states, 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67:858–867. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6731e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshan R, Hamid S, Mashhadi SF. Non-communicable diseases in Pakistan; a health system perspective. Pakistan Armed Forces Medical Journal. 2018;68(2):394. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks E, Morrow M, Story WT, Shelley KD, Shanklin D, Rahimtoola M, et al. Beyond the building blocks: Integrating community roles into health systems frameworks to achieve health for all. BMJ Global Health. 2019;3(Suppl 3):e001384. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayinzoga F, Bijlmakers L. Drivers of improved health sector performance in Rwanda: A qualitative view from within. BMC Health Services Research. 2016;16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Challener D, Tande AJ, Mahmood M, O’Horo JC, Berbani E, Crane SJ. Drive-through testing: A unique, efficient method of collecting large volume of specimens during the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples JE, Dziuban EJ, Fischer M, Cragan J, Rasmussen SA, Cannon MJ, et al. Interim guidelines for the evaluation and testing of infants with possible Congenital Zika Virus infection. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65(3):63–67. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6503e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software. (2017). MAX QDA (Version 2018) [Computer software]. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.maxqda.com.

- World Health Organization. (2007). Everybody’s business - strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2010). Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: A handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from https://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/monitoring/en/.

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zomerdijk LG, Voss CA. Service design for experience-centric services. Journal of Service Research. 2010;13(1):67–82. doi: 10.1177/1094670509351960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]