Abstract

Recent progress in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) technologies suggest that iPSC application in regenerative medicine is a closer reality. Numerous challenges prevent iPSC application in the development of numerous tissues and for the treatment of various diseases. A key concern in therapeutic applications is the safety of the cell products to be transplanted into patients. Here, we present novel method for detecting residual undifferentiated iPSCs amongst directed differentiated cells of all three germ lineages. Marker genes, which are expressed specifically and highly in undifferentiated iPSC, were selected from single cell RNA sequence data to perform robust and sensitive detection of residual undifferentiated cells in differentiated cell products. ESRG (Embryonic Stem Cell Related), CNMD (Chondromodulin), and SFRP2 (Secreted Frizzled Related Protein 2) were well-correlated with the actual amounts of residual undifferentiated cells and could be used to detect residual cells in a highly sensitive manner using qPCR. In addition, such markers could be used to detect residual undifferentiated cells from various differentiated cells, including hepatic cells and pancreatic cells for the endodermal lineage, endothelial cells and mesenchymal cells for the mesodermal lineage, and neural cells for the ectodermal lineage. Our method facilitates robust validation and could enhance the safety of the cell products through the exclusion of undifferentiated iPSC.

Subject terms: Stem-cell biotechnology, Stem-cell biotechnology, Induced pluripotent stem cells, Induced pluripotent stem cells

Introduction

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technologies could pave the way for patients to reap the benefits of regenerative medicine and therapies1–3. Theoretically, iPSC have the potential to differentiate into any type of cells in our body, and protocols have been developed to differentiate iPSCs into specific cell types, including neural cells, cardiomyocytes, chondrocytes, retinal pigment epithelial cells, pancreatic islet cells, and hepatocytes4. Several approaches, in addition to standard 2D culture, have been explored for direct cell differentiation. Organoid technology has emerged as a tool for mimicking miniaturized organs from stem cells, and culturing them into buds using iPSC technologies5–12. We also previously developed a method for the generating multicellular 3D miniaturized liver primordia organoids from pluripotent stem cells13–15.

To apply such iPSC technologies to regenerative medicine and offer their potential benefits to patients, researchers are working to ensure the functionality and safety of iPSC-derived cells following transplantation. For example, the safety of iPSC has been enhanced through various approaches, such as the application of L-Myc as opposed to c-Myc proteins, use of non genome-integrative methods, and the validation of undifferentiated cells16,17. Nevertheless, it is essential to ensure that the undifferentiated cells are excluded from differentiated cells, which could be used in transplantation activities, since cells exhibiting pluripotency have the capacity to generate teratomas18–20.

Several reports have explored strategies of excluding and/or detecting undifferentiated cells in differentiated cells21–23. One method cultures undifferentiated cells among differentiated cells while maintaining an iPSC state, and could detect undifferentiated cells in differentiated cells efficiently22. In addition, growth medium could be modified to exclude residual undifferentiated cells from cardiomyocytes24. Cell sorting with cell surface markers has been reported to purify intermediate cell lineages used to derive dopaminergic neurons25, while LIN28A (Lin-28 Homolog A) could be used to detect residual undifferentiated cells in iPSC-derived differentiated retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells21, which was already applied to patients. Such methods are often optimized for specific differentiation protocols and are not always applicable to the other lineages. Therefore, it is critical to develop more versatile methods to facilitate the detection of residual undifferentiated cells in differentiated cells. Here, we report a method for detecting undifferentiated cells amongst iPSC-derived cells in all three germ layers.

Results

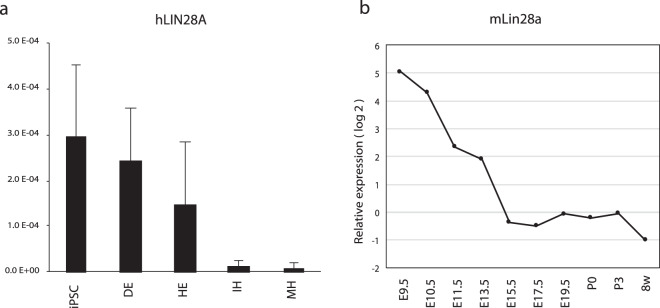

Lin28A is not suitable for detecting undifferentiated iPSC in hepatic differentiation

LIN28A, formerly referred to as LIN28, has been reported previously to be a marker for residual undifferentiated iPSC in iPSC-derived RPE3. LIN28A expression was examined to validate the potential application of LIN28A in the detection of residual undifferentiated cells during iPSC differentiation toward hepatic lineage cells. While LIN28A expression was high in hepatic endoderm (HE), it remained unaltered in the immature hepatocyte (IH) stage (Figs. 1a and S1). We considered two possible explanations for the observation. One is that LIN28A is expressed in hepatic lineage cells and; therefore, is not suitable for the detection of undifferentiated iPSC in hepatic lineage cells. The other potential explanation is LIN28A is actually the undifferentiated iPSC marker and there were undifferentiated iPSCs in the differentiated cells in the present study. To explore the possibility of the above cases, we evaluated gene expression in the developing mouse liver and observed that hepatic cells expressed some amounts of mouse Lin28a during liver development (Fig. 1b). This result suggests that Lin28a express during hepatocyte differentiation and might not suitable to detect undifferentiated cells in differentiated, but immature hepatic progenitors.

Figure 1.

LIN28A is not suitable for detecting undifferentiated iPSC during hepatic differentiation. (a) Human LIN28A expression during hepatic differentiation from iPSC. DE, definitive endoderm; HE, hepatic endoderm; IH, immature hepatocyte; MH, mature hepatocyte. The relative expression levels were normalized by the amount of 18S rRNA in each sample. (b) Mouse Lin28a expression in hepatic cells during liver development. For samples from embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) to post natal day 3 (P3) total RNA was isolated from nonhematopoietic (CD45 − TER119−) cells. For 8 week (8w) old sample, hepatic cell fraction was isolated by centrifugation.

Subsequently, we evaluated whether undifferentiated iPSCs were present in the differentiated cells in the present study. We utilized “re-seeding method”, by which we re-seeded differentiated cells and cultivated them for ~1 week in iPSC maintenance state to derive undifferentiated cell colonies to facilitate the direct observation of the contamination with undifferentiated cells in the culture22.

To validate this re-seeding method, we spiked-in (mixed) undifferentiated iPSC to the differentiated cells and detected at least 0.0025% of spiked-in undifferentiated cells in our condition (data not shown). Notably, the method is robust and the more cells are seeded in culture, the more the detection limit can be lowered, although it requires at least 1 week to grow undifferentiated cell colonies. No undifferentiated cell colonies were detected from HE cells when cells were seeded at densities of 8 × 104 cells/cm2 and 1.6 × 105 cells in three independent experiments. The results indicate that LIN28A is not suitable for detecting undifferentiated iPSC in hepatic differentiation (Fig. 1 and see below).

Identification of a marker gene for residual undifferentiated iPSC

We have previously reported the use of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) for the reconstruction of hepatocyte-like lineage development from pluripotency under two-dimensional culture14. We explored our scRNAseq data, and we selected genes consistent with following criteria: (1) Specific expression in the iPSC stage to exclude genes expressed during directed hepatic differentiation, (2) high expression in iPSC to facilitate high-level and sensitive detection even at low levels of undifferentiated iPSC contamination, and (3) considerable difference in expression level between iPSC and target cells i.e., hepatic endoderm (HE) cells.

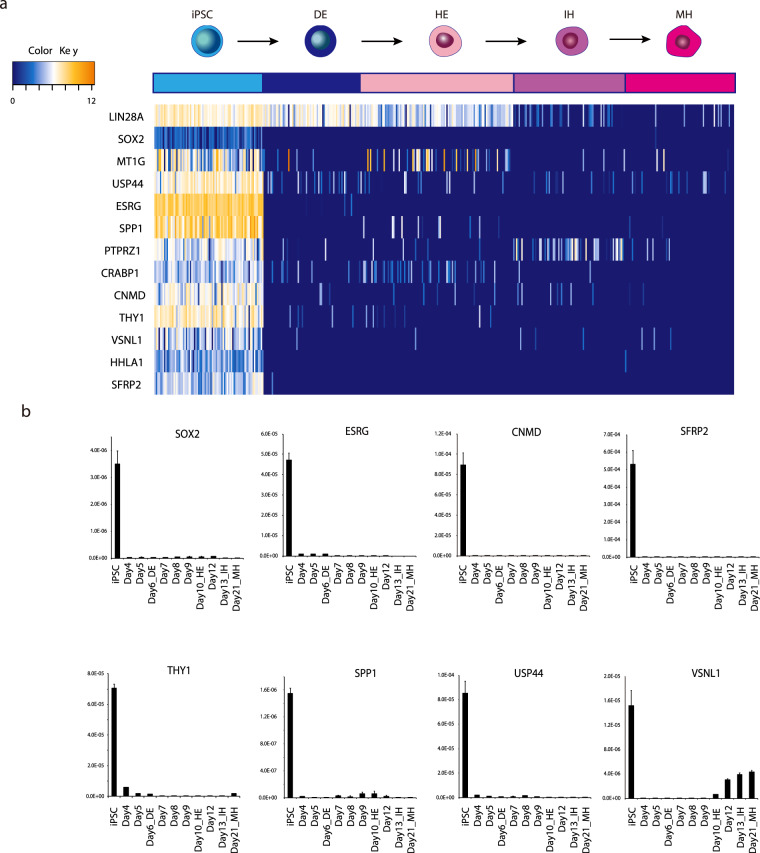

Twelve genes were selected as illustrated in Fig. 2a which expressed highly, specifically, and abundantly in iPSC. Marker gene expression was confirmed using quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), and ESRG (Embryonic Stem Cell Related), SFRP2 (Secreted Frizzled Related Protein 2), CNMD(Chondromodulin, also referred to as LECT1), SOX2 (SRY-Box 2), THY1 (Thy-1 Cell Surface Antigen), USP44 (Ubiquitin Specific Peptidase 44), VSNL1 (Visinin Like 1), and SPP1 (Secreted Phosphoprotein 1) were selected for further analyses (Fig. 2b). Marker genes were also checked using several iPSC lines to exclude clone specific variations. We confirmed that the genes were down-regulated considerably following the stimulation of differentiation in several other iPSC lines (Fig. S2). We estimated the actual RNA count of these markers in one undifferentiated iPSC by droplet digital PCR (Fig. S3). These results show that not only the expression level in undifferentiated iPSC is critical but also the downregulation in differentiated cell is important.

Figure 2.

Identification of candidate genes for detecting undifferentiated iPSC during hepatic differentiation. (a) Single-cell RNA sequence analysis identified novel candidate genes. Upper illustration and color column represents differentiation lineages from undifferentiated iPSC to mature hepatocyte (MH). DE: definitive endoderm, HE: hepatic endoderm, IH: immature hepatocyte. (b) qPCR analysis of marker gene candidates during hepatic differentiation. Down regulation of gene expressions during hepatic differentiation. The relative expression levels were normalized by the amount of 18S rRNA in each sample.

The results indicate that the genes fit the criteria described above as candidate marker genes for detecting residual undifferentiated cells in differentiated cells.

Correlation of marker gene expression with actual residual undifferentiated cells and detection using single-molecule FISH

We explored whether expression levels of the candidate genes are correlated to residual undifferentiated iPSCs. To obtain actual residual undifferentiated iPSCs rather than spiked-in undifferentiated iPSC, we evaluated various iPSC derived cells and found that if we used iPSC which passage number was over 35, doubling time become faster than 20.5 hr, which turn out to related to increase the residual undifferentiated iPSC number. We used this over passaged cells as a model of actual residual undifferentiated iPSCs after differentiation (Fig. S4).

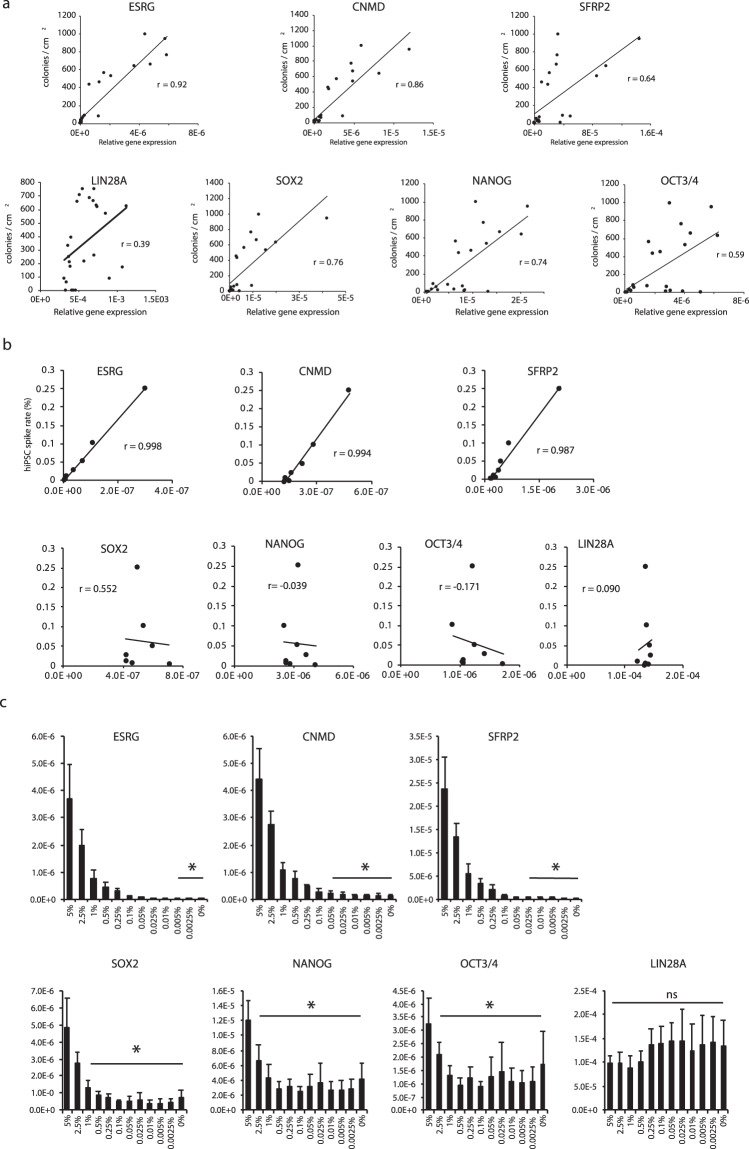

Various samples were evaluated for gene expression and simultaneously cultured in iPSC maintenance state. ESRG, CNMD, SFRP2, SOX2, and NANOG were well-correlated26,27 (r ≥ 0.6) with the numbers of residual undifferentiated iPSCs, whereas OCT4 and LIN28A were not well-correlated with residual iPSC (Fig. 3a). Spike-in experiments were performed to determine the correlation between low number of spiked-in iPSC and gene expression. ESRG, CNMD, SFRP2 were well-correlated (r ≥ 0.9) with the number of spike-in undifferentiated iPSCs, whereas SOX2, OCT4 and LIN28A were not well-correlated with the number of spiked-in iPSC (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Correlation of marker gene expression with practical residual undifferentiated cells. (a) Correlation between gene expression and residual undifferentiated iPSC in HE. X–axes represent relative gene expression by qPCR and Y–axes represent actual residual colony number per cm2 when HE cells were re-seeded at a density of 8 × 104 cells/cm2. (b) Correlation between spiked-in iPSC and gene expression of novel marker genes. X–axes represent relative gene expression by qPCR and Y–axes represent spiked-in undifferentiated iPSC percentage. (c) Detection limits of residual undifferentiated iPSC for novel markers and well-known iPSC marker genes. *p values <0.05. The all relative expression levels were normalized by the amount of 18S rRNA in each sample.

Detection limits were calculated by evaluating whether some spiked-in cells could be distinguished from non spiked-in cells the HE sample. Detection limits for ESRG, CNMD and SFRP2 were 0.005%, 0.025%, and 0.025%, respectively (Fig. 3c), while the detection limits for SOX2, NANOG, and OCT4 were 1%, 5%, and 2.5%, respectively. LIN28A could not discriminate 5% of undifferentiated iPSC in the spiked-in sample from HE cells. Therefore, ESRG and CNMD were considered suitable for sensitive detection of residual undifferentiated cells.

ESRG and CNMD are robust residual undifferentiated iPSC markers for lineages derived from three germ layers

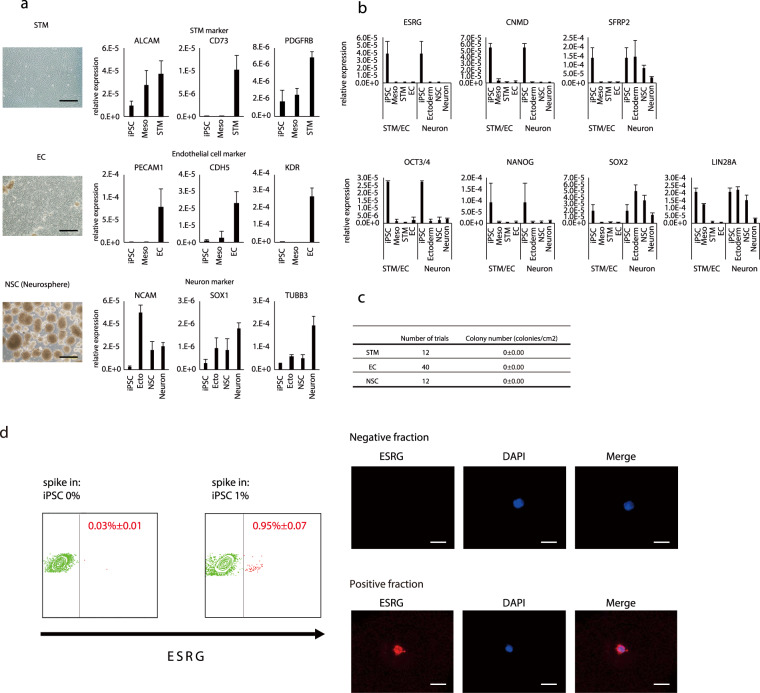

We wondered whether the marker genes could be applied in the detection of residual undifferentiated iPSC in iPSC derived lineage from other germ layers. Hepatic cells belong to the endodermal cell lineage. We also examined pancreatic cells, as endodermal lineage cells. Marker gene expression was downregulated markedly following differentiation and no residual undifferentiated cells were detected by cultivation (data not shown). Subsequently, we evaluated iPSC derived septum transversum mesenchyme (STM)/mesenchymal cells (MC) and endothelial cells (EC) as mesoderm derived lineages15. The marker genes were down-regulated in STM/MC and EC (Fig. 4a). Residual undifferentiated iPSC were not detected by the cultivation method. The results suggest that the markers were also useful for mesoderm evaluation.

Figure 4.

Novel markers were suitable for detecting residual cells from three germ lineages. (a) Mesoderm and ectoderm lineage cells were successfully differentiated based on gene expressions. Representative image of differentiated cells and marker gene expressions of each lineage. bar: 500 um. (b) Marker genes were down-regulated in the course of differentiation in each lineage and (c) residual iPSC in each lineage. The relative expression levels were normalized by the amount of 18S rRNA in each sample. (d) smFISH detection of undifferentiated cells by ESRG gene expression with flow cytometry. Positive fraction specifically included stained, ESRG-positive cell. bar: 10 um.

Neuronal cell lineage was also evaluated as an ectoderm derived lineage. The marker genes, ESRG and CNMD, but not SFRP2, were down regulated in neural crest cells and neural stem cells (Fig. 4a–c), while LIN28A was not down-regulated during differentiation within the culture period. Residual undifferentiated iPSC were not detected using the cultivation method. The results suggest that the marker genes were also suitable for ectoderm derived lineages. To consolidate the above observations, we employed another method to derive three germ layer derived cells using a commercially available differentiation kit (Fig. S5). Three germ lineage cells were derived and the qPCR analysis and the cultivation evaluation were performed. According to the results, ESRG and CNMD are highly sensitive and robust markers for detecting residual undifferentiated cells in human iPSC-derived cell products differentiated into each of the three germ cell lineages. We also explored another method for detecting ESRG expression to expand the range of markers that could be applied. We applied the single-molecule FISH (smFISH) method followed by flow cytometry analysis. According to the results, smFISH was also applicable for the detection of ESRG + cells in the differentiated cells (Fig. 4d).

Discussion

The application of human iPSC in regenerative medicine could benefit patients suffering from various diseases greatly. Researchers and doctors are attempting to deliver novel therapies as rapidly as possible, while carefully assessing the safety of such novel therapies. Here, we describe a novel method for validating residual undifferentiated iPSC in differentiated cells. We evaluated LIN28A as a marker for residual undifferentiated cells and found it unsuitable for detecting residual cells in hepatocytic differentiation, in addition to in the early stages of neuronal differentiation.

We identified several marker genes suitable for hepatic differentiation, including ESRG, CNMD, and SFRP2. These marker genes satisfied several requirements as marker for residual undifferentiated iPSC. These genes highly and specifically expressed in the iPSC stage. They down-regulate immediately after differentiation and considerable difference in expression level between iPSC and target cells i.e., HE. These characteristics enables high-level and sensitive detection even at low levels of undifferentiated iPSC contamination, In addition, ESRG and CNMD were suitable for other cells derived from other germ layers. Therefore, the method is rapid and robust for the detection of residual undifferentiated iPSC in cells derived from three germ layers. The markers identified in the present study include well-known iPSC genes such as ESRG; however, not all “iPSC genes” are suitable for detecting residual undifferentiated cells. In fact, although SOX2 or NANOG are the well-known iPSC genes that are expressed exclusively in iPSC, detection limits of the two genes for residual iPSC were relatively high compared to the genes identified in the present study. LIN28A have been reported to be a residual cell marker, however we observed low relation to the gene expression and the actual residual cell number. Several other methods for detection and elimination of undifferentiated iPSC were also reported including utilizing microRNA-302, cytotoxic viral vectors, rBC2LCN lectin, drug, antibody, or methionine removal. The detection limits of these method might be differ between target products and also, adaptation of these method to the on going research may require additional evaluation of product and optimization of established differentiation protocol23,24,28–30. Nevertheless, it is important to validate whether the detection method employed is suitable for their cell products.

Currently, numerous studies are exploring the potential application of iPSC technologies in in regenerative medicine, so that actual application could be witnessed in the near future. Although there are no full-proof strategies for ensuring the safety of technologies, it remains critical to evaluate technologies and products adopted in cell therapies. There are at least two bottlenecks in any method used to detect contamination of undifferentiated iPSC when large numbers of cells are being evaluated. If the large numbers of cells were analyzed over detection limits, the signal of residual iPSC would be suppressed by the signals from other differentiated cells. In addition, there are limitations with regard to the amount of products that could be input in a validation assay, such as the amount of cDNA that could be subjected to a qPCR. To overcome such limitations to some extent, cells to be evaluated should be split into multiple wells and run qPCRs in dozens of wells. It is also critical to develop a method much more sensitive than qPCR to address such limitations. Nevertheless, our method provides simple, highly-sensitive and robust method for validating, and, in turn, enhancing the safety of cell product by facilitating the exclusion of contaminants such as undifferentiated iPSC. We have previously developed a method for generating multicellular 3D miniaturized liver primordia organoids (iPSC-liver bud: iPSC-LB) from pluripotent stem cells13,14. In addition, we recently reported the generation of an iPSC-liver buds entirely from iPSC (all iPSC-LB)15, including iPSC-HE, iPSC-EC and iPSC-STM/MC. The method presented here could be applied in the validation of the safety of all-iPSC LBs in clinical settings.

Methods

Human iPSC and their culture

Human iPSC lines, TkDA3-4 was kindly provided by University of Tokyo (Dr. Koji Eto and Dr. Hiromitsu Nakauchi), and 1231A3, 1383D2, 1383D6, Ff-I01, and Ff-I01s04 were provided by Kyoto University (Dr. Shinya Yamanaka, Dr. Keisuke Okita, and Dr. Masato Nakagawa). All iPSC lines were maintained on Laminin 511-E8 fragment (iMatrix-511™, kindly provided by Nippi,Inc.)-coated dishes in StemFit® AK02N (Ajinomoto Co., Inc.). A detailed procedure for differentiating hepatocytes has been described previously15. Briefly, the cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 2% B27, 50 ng/ml Wnt-3a, and 100 ng/ml activin A for six days to derive the DE. KnockOut DMEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 20% KnockOut serum replacement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% DMSO, 0.1 mM 2-ME, 0.5% L-glutamine, and 1% NEAAs was used to derive the HE and IHs. HBM (Lonza Bioscience) supplemented with the Single QuotesTM kit without EGF (HCM without EGF), 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), dexamethasone, and OSM was used to derive MHs.

The use of human iPSC was approved by the ethical committee at Yokohama City University and the University of Tokyo.

Detection of residual undifferentiated iPSC

To detect and quantify the residual undifferentiated cells in differentiated cells, we employed a method described by Tano et al.22. Briefly, cells were dissociated with trypsin-EDTA and seeded with StemFitAK02 medium on lamin511-E8-coated dishes in the presence of Rock inhibitor Y-27632 at a density of 8 × 104 cells/cm2. The medium was changed every day with StemFitAK02 medium without Rock inhibitor. After cultivation for seven days, the cells were immunostained with SOX2 antibody and SOX2 + colonies were counted. One colony was considered derived from one residual undifferentiated cell.

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cell membranes were permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS (PBST) for 10 min and blocked with 5% FBS in PBST. Primary antibodies against SOX2 and TRA-1-60 were applied (Cell Signaling Technologies) followed by staining with secondary antibody.

Microscopy and colony counting

Whole-well images after SOX2 and Tra-1-60 immunostaining were obtained using a fluorescence microscope (BZ-X710, KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan). Colonies were counted manually and described in numbers per square cm.

Undifferentiated iPSC spike-in

Undifferentiated iPSC were spiked-in, i.e., mixed into HE cells at proportions ranging from 0.0025% to 5% as indicated in the figures.

Human iPSC-EC, STM and NSC differentiation

Endothelial cells and mesenchymal cells were derived as described previously15. iPSC-NSC were derived as described previously31. Gene expression was evaluated using qPCR and flow cytometry. Following antibodies were used for flow cytometric analysis: PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD140b (PDGFRB; 558821, BD Biosciences); APC-conjugated anti-human CD166 (ALCAM; 130-119-809, Miltenyi Biotec); anti- human CD105, human CD73, and human CD90 (MSC phenotyping kit; 130-095-198, Miltenyi Biotec); FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD31 (557508, BD Biosciences); PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD144 (561714, BD Biosciences).

Human iPSC- trilineage differentiation

Alternative three-germ layer derived cells were differentiated using a commercially available kit, STEMdiff Trilineage Differentiation Kit (Stem Cell Technologies). Cells were derived according to manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was evaluated using qPCR. Immunostaining was performed using a FOXA2 (07-633, Millipore) and a SOX17 (AF1924, R&D) for the endoderm, T (AF2085, R&D) and NCAM (362502, BioLegend) for the mesoderm, PAX6 (ab5790, abcam), and a NESTIN (MAB5326, Millipore) for the ectoderm.

Gene expression analysis

For gene expression analysis of developing the mouse hepatocyte, published microarray data were reanalyzed (GSE46631)13. Published single cell RNA sequence data (GSE81252 and GSE96981) were reanalyzed using R studio (https://www.rstudio.com/)14. qRT-PCR analyses were performed according to standard procedures using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and the Universal ProbeLibrary (Roche). smFISH procedures were performed using branched DNA probes as described previously32.

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)

The cDNA was prepared as described above. The ddPCR reaction mixtures were composed as follows: 1 × ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP) (Bio-Rad), 1 μM forward and reverse primers, and 250 nM UPL probe (Roche), and 12.5 ng of cDNA. The Droplets were generated using a QX200 droplet generator (Bio-Rad) and PCR reaction was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of a thermal profile comprising 15 s at 95 °C and 60 s at 60 °C, and followed by 10 min at 98 °C and kept at 15 °C. After the PCR, the samples were analyzed using a QX200 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad) and QuantaSoft (Bio-Rad). The fluorescence amplitude thresholds were manually determined for each gene by comparing the distribution of the signals of negative controls (distilled water). The number of copies of target per cell (estimated as 10 pg of RNA/cell33) was calculated as concentration (cps/20 μL)/(12.5 ng/20 μL)/1000 × 10.

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± SD of independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using the Student’s t-test for differences in gene expression and statistical significance of the differences in the amounts of albumin produced were assessed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by AMED Research Center Network for Realization of Regenerative Medicine (HT), Project for Developing Innovation Systems from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan(HT), Grants-in-Aid 19H03718, 18K19589 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (KS) and AMED Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREATE), 17944438 (KS), Grants-in-Aid 17K10517 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (YU).

Author contributions

K.S. and H.T. conceived and designed the study and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. K.S., S.T., T.K., K.I., R.Y., Y.H., E.K., J.G.C., B.T., Y.U., S.O. performed the experiments and analyzed the data with the technical guidance and expertise of K.S., Y.U. and H.T. provided financial and intellectual support.

Competing interests

R.Y. is employed by Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd. Other authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Keisuke Sekine, Email: ksekine@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Hideki Taniguchi, Email: rtanigu@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-66845-6.

References

- 1.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:183–193. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter MK, Frey-Vasconcells J, Rao MS. Developing safe therapies from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:606–613. doi: 10.1038/nbt0709-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandai M, et al. Autologous Induced Stem-Cell–Derived Retinal Cells for Macular Degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:1038–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabar V, Studer L. Pluripotent stem cells in regenerative medicine: challenges and recent progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:82–92. doi: 10.1038/nrg3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasai Y. Cytosystems dynamics in self-organization of tissue architecture. Nature. 2013;493:318–326. doi: 10.1038/nature11859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasai Y. Next-generation regenerative medicine: Organogenesis from stem cells in 3D culture. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bredenoord AL, Clevers H, Knoblich JA. Human tissues in a dish: The research and ethical implications of organoid technology. Science (80−) 2017;355:eaaf9414. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi J. Stem cells and regenerative medicine for neural repair. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2018;52:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancaster MA, et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature. 2013;501:373–379. doi: 10.1038/nature12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eiraku M, et al. Self-organizing optic-cup morphogenesis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;472:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature09941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spence JR, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011;470:105–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takasato M, et al. Directing human embryonic stem cell differentiation towards a renal lineage generates a self-organizing kidney. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:118–26. doi: 10.1038/ncb2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takebe T, et al. Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature. 2013;499:481–484. doi: 10.1038/nature12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camp JG, et al. Multilineage communication regulates human liver bud development from pluripotency. Nature. 2017;546:533–538. doi: 10.1038/nature22796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takebe T, et al. Massive and Reproducible Production of Liver Buds Entirely from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2017;21:2661–2670. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okita K, et al. A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakagawa M, et al. A novel efficient feeder-free culture system for the derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:3594. doi: 10.1038/srep03594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham JJ, Ulbright TM, Pera MF, Looijenga LHJ. Lessons from human teratomas to guide development of safe stem cell therapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:849–857. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hentze H, et al. Teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells: Evaluation of essential parameters for future safety studies. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takayama K, et al. Generation of safe and therapeutically effective human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells for regenerative medicine. Hepatol. Commun. 2017;1:1058–1069. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroda, T. et al. Highly sensitive in vitro methods for detection of residual undifferentiated cells in retinal pigment epithelial cells derived from human iPS cells. Plos One7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Tano K, et al. A novel in vitro method for detecting undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells as impurities in cell therapy products using a highly efficient culture system. Plos One. 2014;9:e110496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tateno H, et al. Elimination of Tumorigenic Human Pluripotent Stem Cells by a Recombinant Lectin-Toxin Fusion Protein. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sougawa N, et al. Immunologic targeting of CD30 eliminates tumourigenic human pluripotent stem cells, allowing safer clinical application of hiPSC-based cell therapy. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:3726. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21923-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kikuchi T, et al. Human iPS cell-derived dopaminergic neurons function in a primate Parkinson’s disease model. Nature. 2017;548:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nature23664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber J. C, L. D. Statistics and Research in Physical Education. in 59–64, 222 (Mosby Distributed by Kimpton, 1970).

- 27.Mason RO, Lind DA, M. W. Statistics. An. Introduction. (1983).

- 28.Tateno, H. et al. Oriented immobilization of rBC2LCN lectin for highly sensitive detection of human pluripotent stem cells using cell culture supernatants. J. Biosci. Bioeng., 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.08.003 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Parr, C. J. C. et al. MicroRNA-302 switch to identify and eliminate undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep., 10.1038/srep32532 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Kono, K. et al. Development of selective cytotoxic viral vectors for concentration of undifferentiated cells in cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep., 10.1038/s41598-018-36848-5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Imaizumi K, et al. Controlling the Regional Identity of hPSC-Derived Neurons to Uncover Neuronal Subtype Specificity of Neurological Disease Phenotypes. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:1010–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Battich N, Stoeger T, Pelkmans L. Image-based transcriptomics in thousands of single human cells at single-molecule resolution. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsköld, D. et al. Full-length mRNA-Seq from single-cell levels of RNA and individual circulating tumor cells. Nat. Biotechnol., 10.1038/nbt.2282 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.