Abstract

Although extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma (ENA) is a rare condition, its diagnosis should be considered during differential diagnosis of nasal masses. We report a rare case of ENA originating from the left lateral side of nasal tip.

A 43-year-old man with an ENA mass located on the left lateral side of the nasal tip presented to our hospital. The nasal mass caused nasal obstruction and swelling at the nasal tip and was surgically removed. Histopathological examination revealed ENA. The patient is being followed up and remains free of disease.

ENAs are rare and differ from nasopharyngeal angiofibromas regarding clinical and radiological features. Although it is rare, the diagnosis should be considered during differential diagnosis of a patient with one sided nasal mass and/or with refractory epistaxis, regardless of the patient’s age or sex.

Keywords: Angiofibroma, benign tumor, extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma, nose

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) is a histologically benign, non-capsular, and vascular tumor that develops from the nasopharynx and demonstrates a tendency to spread to surrounding tissues in all directions. It is usually seen in adolescent male patients aged between 7 and 19 years and causes local destruction.[1, 2]

Extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas (ENA) are rarely observed, and their clinical and radiological features differ from those of nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. They can be seen in all age groups and women. They are less vascular and can arise from different regions. Symptoms vary by region. They are most commonly seen in the maxillary sinus, followed by the ethmoid sinus and the nasal septum. Symptoms vary according to its localization.[3, 4]

We report a rare case of ENA arising from the nasal dorsum and localized in the nasal tip and the lateral nasal region.

Case Report

A 43-year-old male patient was admitted to our polyclinic complaining of inability to breathe through his left nostril for 7–8 months and swelling on nasal tip of the same side for several months. He had a history of nasal trauma that he experienced 17 years ago. On physical examination, a mass lesion on his left nasal dorsum was palpated under the skin, which caused skin swelling. The mass lesion was seen to arise from the junction between the septum and alar cartilage on the left side, close the internal nasal valve, and continued on the left as a swelling in the nasal dorsum. On physical examination of the head and neck, millimetric lymphadenopathies were palpated in the upper jugular region on the left side.

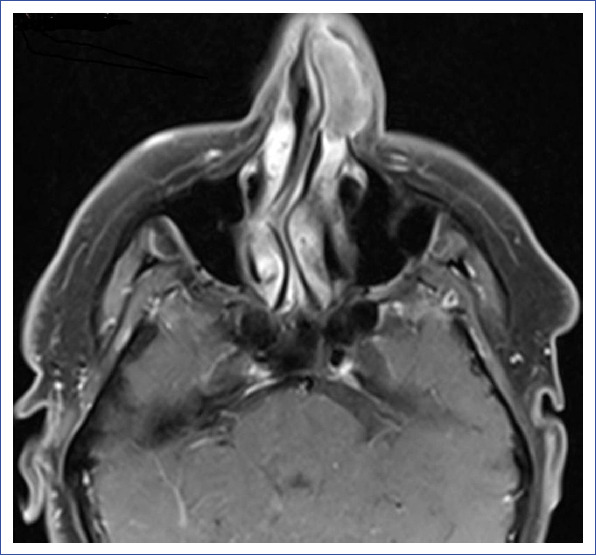

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the paranasal sinuses showed a benign mass lesion measuring 33×10 mm, including the septum alar cartilage, and obliterating the left nasal vestibule and the passage almost completely (Fig. 1, 2).

Figure 1.

At the axial section of the paranasal sinus MR image of the patient, a benign mass lesion, measuring 33×10 mm in size, encircling the septum alar cartilage, and obliterating the left nasal vestibule and passage almost completely is seen.

Figure 2.

Coronal sectional image of the mass lesion obliterating the left nasal cavity obtained during paranasal sinus MR of the patient.

In positron emission tomography imaging obtained upon observation of bilateral nodes with spheric configuration, a mass lesion filling left anterior nasal cavity, involving the septum, and deviating it to the right was observed. The mass lesion on the neck with axial dimensions of 31×19 mm invaded the skin-subcutaneous tissue and bone tissue laterally and demonstrated FDG uptake at the level of malignancy (SUV max: 4.3).

Computed tomography (CT) of the paranasal sinuses revealed a large soft tissue mass lesion originating from the anterior cartilage component of the septum that completely obliterated the left anterionasal passage. This mass lesion surrounded the external nares from superior and extended to the alar loge.

Histopathological examination of fine needle aspiration biopsy specimen yielded a nondiagnostic result. After the incisional biopsy specimen was diagnosed as fibrosis, the mass was surgically excised en bloc under general anesthesia.

During operation, it was observed that the mass extended medially toward the nasal tip and septum, laterally to apertura priformis, and surrounded the lateral crus of the alar cartilage inferiorly. The mass was yellowish and semisolid and was localized under the skin. Histopathological examination showed markedly increased vascular structures with specific CD34 immunohistochemical staining, and the lesion was reported as angiofibroma (Fig. 3). The patient is still being followed up without adverse sequelae.

Figure 3.

Histopathological examination demonstrating marked hypervascularity in the dense fibrous stroma with specific CD34 immunohistochemical staining (Magnification 100×).

Discussion

JNA is a histologically benign, non-capsular, and vascular-originated tumor developed from the nasopharynx, with a tendency to spread to surrounding tissues in all directions. It is usually seen in adolescent male patients aged between 7 and 19 years and causes local destruction.[1, 2] It accounts for 0.5% of head and neck cancers. It mainly originates from structures surrounding the superoinferior part of the sphenopalatine foramen and progresses slowly and insidiously. Its etiology is not fully known. Its strong correlation with age and gender indicates a potential hormonal disturbance of the pituitary–androgen–estrogen system, but there is still no evidence to prove this hypothesis.[3] Progressive nasal obstruction and recurrent epistaxis are the most common symptoms.[5]

Angiofibromas have been reported as sporadic tumors with extranasopharyngeal location. Nomura et al. and Huang et al. reported cases of angiofibromas originating from inferior and middle conchas, respectively.[1, 2] Szymanska et al.[3] reported a total of 10 cases with ENA. These cases originated from the oral cavity (n=1), infratemporal fossa (n=1), and nasal septum (n=7).

ENAs are rarely observed tumors, and their clinical and radiological features differ from those of nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. They can be observed in all age groups and women. They are less vascular and can originate from different regions. Their symptoms vary by region. They are most frequently observed in the maxillary sinus, followed by the ethmoid sinus and nasal septum.[3, 4] The present case was a 43-year-old male patient, and the mass lesion was located in the nasal dorsum, which was very rarely reported for this tumor location.

Histopathologically, in typical JNA, numerous large, irregular vessels of single-layer endothelial cells embedded in the fibrous stroma are observed. The vascular component is very numerous and can cause excessive bleeding after surgery and biopsy.[3, 6] At the same time, this vascular content is characterized by intense contrast enhancement on CT and MRI. Histopathologically, ENA belongs to a more heterogeneous group. The vascular component is not always dominant. Therefore, intense contrast enhancement may not occur. Because of their different localizations, radiological findings also vary.[7] There was no evidence of excessive bleeding during fine needle aspiration biopsy and incisional biopsy in this patient.

Surgery is the first treatment alternative in ENAs, as is the case in JNAs. The surgical approach is determined according to the location and size of the tumor. Radiotherapy can be used for lesions that cannot be removed. No recurrent cases have been reported in the literature.

In this article, we presented a rare case of ENA involving the nasal tip and lateral nasal region. Although the age of the patient, the location of the mass lesion, and the result of the incisional biopsy material removed us from the diagnosis of angiofibroma, histopathological examination of the mass was reported as angiofibroma. Although nasal tip and lateral nasal region are very rare locations for this tumor, angiofibromas should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of the tumors of this region.

As a result, ENA is a clinically and radiologically distinct entity from JNA in that it can be seen in every age group and in women, originates from different regions, it is relatively less vascular, and it may present with different symptoms depending on the region from which it originates. Although it is seen rarely, in cases with unilateral nasal masses and in cases with treatment-refractory epistaxis, it should be kept in mind during differential diagnosis regardless of the age and sex of the patient.

Disclosures

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the case report and the accompanying images.

Authorship contributions: Concept – B.T., Ö.U., M.A., Ş.T.B., B.U.C.; Design – B.T., Ö.U., M.A., Ş.T.B., B.U.C.; Supervision – M.A., B.U.C.; Materials – B.T., Ş.T.B.; Data collection &/or processing – B.T., Ö.U., M.A., Ş.T.B.; Analysis and/or interpretation – Ö.U., M.A., B.U.C.; Literature search – B.T., Ö.U.; Writing – B.T., M.A.; Critical review – M.A., B.U.C.

References

- 1.Nomura K, Shimomura A, Awataguchi T, Murakami K, Kobayashi T. A case of angiofibroma originating from the inferior nasal turbinate. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2006;33:191–3. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang RY, Damrose EJ, Blackwell KE, Cohen AN, Calcaterra TC. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;56:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szymanska A, Szymanski M, Morshed K, Czekajska-Chehab E, Szczerbo-Trojanowska M. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma: clinical and radiological presentation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:655–60. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correia FG, Simões JC, Mendes-Neto JA, Seixas-Alves MT, Gregório LC, Kosugi EM. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the nasal septum-uncommon presentation of a rare disease. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:646. doi: 10.5935/1808-8694.20130118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akbas Y, Anadolu Y. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the head and neck in women. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:413–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(03)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Rodriguez L, Rudman K, Cogbill CH, Loehrl T, Poetker DM. Nasal septal angiofibroma, a subclass of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33:473–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerra S, Nazir T, Khan N, Qadri MS, Dar NH. A case of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the ethmoid sinus: a distinct clinical entity at an unusual site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012;91:E15–7. doi: 10.1177/014556131209100217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]