Abstract

Objective

The aim of this clinical trial was to assess the effect of resin infiltration on the progression of proximal caries lesions.

Subjects and Methods

Forty-one patients, aged between 15 and 33 years, with 2 or more non-cavitated proximal caries lesions were included. In 41 of the adolescent and young adults, 45 pairs of proximal lesions with radiological extension into the inner and outer half of the enamel, or into the outer third of the dentin, were randomly allocated to the test groups (resin infiltration application + fluoridated toothpaste and flossing use) or to the control group (fluoridated toothpaste and flossing use). Standardized geometrically aligned digital bitewing radiographs were obtained using individual biting holders. The radiographic progression of the lesions was assessed after 1 year by digital-subtraction radiography. The McNemar test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

In the test group 1/45 of the lesions (2.2%) and in the control group 9/45 of the lesions (20%) showed progression. The caries progression rate of the control group was significantly higher than that of the test group (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Resin infiltration of proximal caries lesions is effective in reducing progression of the lesion.

Keywords: Resin infiltration, Proximal caries, Digital-subtraction radiography

Highlights of the Study

The use of infiltrating resins is an efficient microinvasive treatment for interproximal caries in adolescents and young adults.

This method enables the treatment of lesions in a single session.

No significant adverse events or side effects were observed in patients 1 year following infiltration.

Introduction

Dental caries lesions can be prevented by the application of fluorides, good oral hygiene, and a proper diet. However, with non-compliant patients and increasing progression of lesions, these methods are safe but often not effective [1]. In terms of a restorative approach, particularly for interproximal caries lesions, access to the lesion area requires the removal of considerable amounts of healthy tissue [2]. For this reason, there is a degree of uncertainty about how to determine the individual treatment options, especially for interproximal caries lesions that radiographically extend into the outer and inner enamel or to the outer third of the dentin [3, 4].

Resin infiltration is a novel technology for arresting caries lesions, providing a new intermediary treatment choice between preventive and restorative therapies. In this treatment, the resin material plugs the porosities within the lesion. The resin fully fills the pores within the tooth and stops the progression of caries [5, 6]. The special resins, optimized for rapid capillary penetration, penetrate to a significant depth [7]. A scientific study found that, compared to non-invasive methods (oral hygiene instructions), with resin infiltrant plus oral hygiene measures progression of proximal caries lesions was less likely to occur in permanent teeth after treatment [8]. A recent meta-analysis showed that preventing the progression of non-cavitated caries lesions by using resin infiltration is promising; thus, resin infiltration is proposed as an encouraging non-invasive approach that can be used as an option in addition to non-operative and operative approaches to treatment [9].

The aim of the present study was to assess the effect of resin infiltration on the progression of interproximal caries lesions. It was hypothesized that progression of caries in resin-infiltrated proximal lesions would be significantly reduced compared to non-infiltrated control lesions.

Subjects and Methods

Screening and Baseline Evaluation

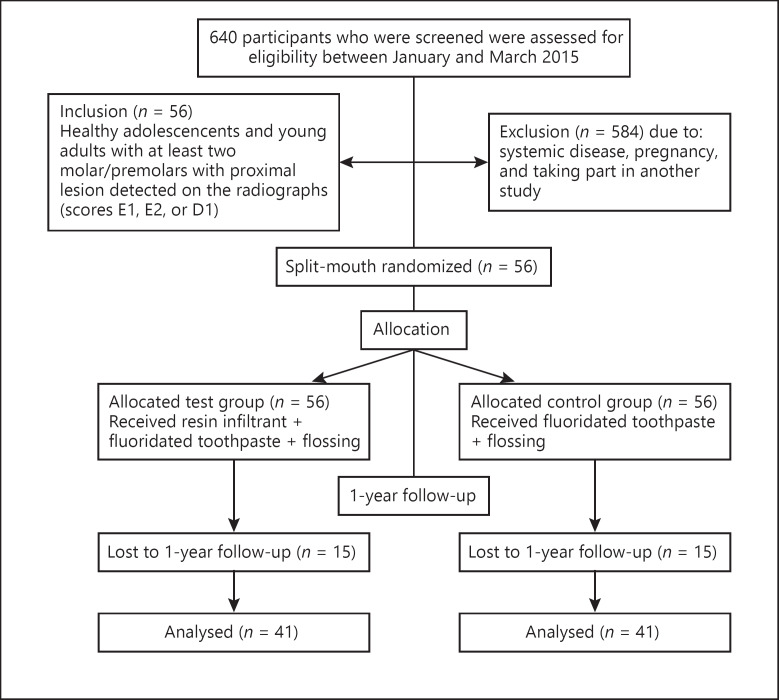

The study design was a split-mouth controlled randomized clinical trial and was registered at www.clinicaltrials.in.th (TCTR identification No. 20190406001). The flow of subjects through the study is outlined in Figure 1. Inclusion criteria were the presence of 2 or more non-cavitated interproximal caries lesions with radiolucencies involving the external and internal half of the enamel up to the outer third of the dentin, age of 15–45 years, and the provision of informed consent. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, systemic disease, and being part of another study.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

From patients admitted to the department of restorative dentistry, eligible interested individuals were examined, and a pair of standardized geometrically aligned digital bitewing radiographs were obtained, using individualized holders (DMG Icon X-ray Holder System, DMG, Hamburg, Germany). The Digoradigital X-ray system (Executive Dental Supply, Burnaby, BC, Canada) was used, operated at 65 KVp and 7 mA, and the exposure time was set at 0.2 s. Lesions were scored by a single experienced examiner under uniform lighting conditions according to the following scores: E0, no radiolucency; E1, radiolucency confined to the outer half of the enamel; E2, radiolucency involving the inner half of the enamel; D1, radiolucency in the outer third of the dentin; D2, radiolucency in the middle third of the dentin, and D3, radiolucency in the inner third of the dentin [10].

Of 640 patients, 56 met the inclusion criteria, gave their informed consent, and were enrolled in the study. However, at the end of the year only 41 patients participated in the evaluation (15 patients refused to participate in the control appointments). Twenty-two premolar and 68 molar teeth were included in the study. For each patient, 1 (38 patients), 2 (2 patients), and 3 pairs (1 patient) of non-cavitated proximal caries lesions (checked with a thin probe without prior tooth separation) with scores E1, E2, and D1 (a total of 45 lesion pairs) were selected [11]. The caries risk of the participants was determined by considering inadequate oral hygiene and fluoride exposure, caries experience (DMFT), gingival health, and dietary habits [12, 13, 14, 15].

Treatment

The allocation of groups was performed using simple randomization. Each patient included in the study had two proximal lesions and was assigned to the control group or to the test group by flipping a coin. If more than two lesions were present, the test and control teeth were selected by the lottery method. The tooth numbers were placed in a jar and mixed thoroughly, after which a researcher chose numbers in a blinded fashion. The first number chosen was in the control group and the second number chosen was in the test group. This lottery method was continued until the selection was completed.

In the test group, the treatment of the lesions was performed by a single trained operator using the resin infiltrant (Icon, DMG). Treatment was conducted using rubber-dam isolation and plastic wedges. The procedure included the following: the plastic strip isolation of adjacent teeth; lesion-surface etching with 15% hydrochloric acid (2 min); rinsing and drying; 95% ethanol and air-drying; resin infiltration with a syringe (3 min); polymerization; infiltrant reapplication (1 min); polymerization.

All patients were advised to use fluoride toothpaste twice a day and to floss once a day. Furthermore, general oral hygiene education and dietary advice were given.

After 1 year, patients were called back for a follow-up examination. Standardized digital bitewing radiographs were obtained using the same individual holders and settings as during the baseline examination. Digital subtraction radiography (DSR) images were then obtained. Radiographs and DSR images were read by an experienced clinical examiner (intra-examiner reliability was assessed), who was blinded with regard to the test and control lesions. First, the radiographic stage of the lesions was assessed. Then, the examiner examined the subtraction radiographs and evaluated whether or not the lesions showed progression. Dark spots in the area of the lesions were interpreted as progression and grayish color (similar to the rest of the tooth) as stable lesions.

To ensure intra-examiner reliability, evaluation of the lesions with DSR was performed twice by the examiner. Inter-measure consistency was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient. The McNemar test was used to analyze differences between the test and the control groups with regard to lesion progression and lesion stages at p < 0.05 [16, 17].

Results

Baseline

The mean age of participants was 20.7 (±5.65; 15–33) years, with 28/41 (68.3%) females and 13/41 (31.7%) males. The mean DMFT was 3.68 (±1.4). Participants were classified as possessing low, moderate, or high caries risk (12.2% low, 53.7% moderate, and 34.1% high).

After 1 Year

The intra-examiner reliability was 0.942 and the confidence interval was 95% (0.913–0.961). Consequently, the measurements were judged to be reliable. There were no statistically significant differences for the caries stages between the test and control groups (p > 0.05; Table 1). Consequently, progression was recorded in 9 of the 45 lesions (20%) in the control group, and in 1 of the 45 lesions (2.2%) in the test group. The caries progression rate of the control group was significantly higher than that of the test group (p < 0.05; Table 2).

Table 1.

Radiographic caries lesion stages at baseline

| Control | Test | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Stage | E1 | 18 | 40.0 | 8 | 17.8 | 0.062 |

| E2 | 20 | 44.4 | 28 | 62.2 | ||

| D1 | 7 | 15.6 | 9 | 20.0 | ||

Table 2.

The percentage of caries lesions progressing after 1 year

| Control | Test | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Not progressing | 36 | 80.0 | 44 | 97.8 | 0.039 |

| Progressing | 9 | 20.0 | 1 | 2.2 | |

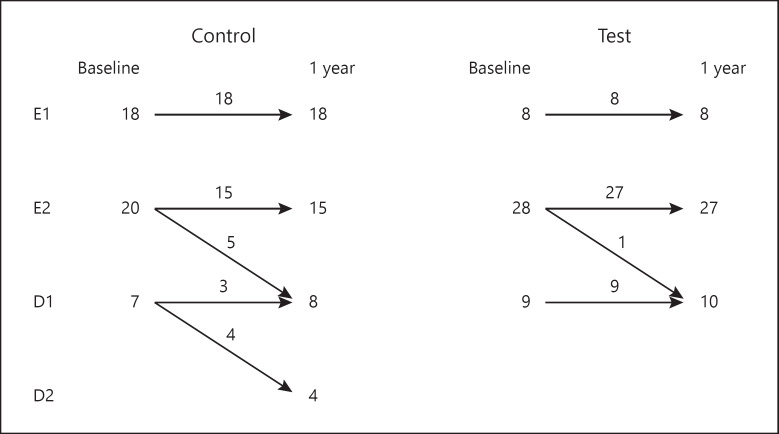

In addition to the described changes of the radiographic stages in the control group, 5 lesions with an E2 radiographic score progressed from E2 to D1 and 4 lesions with a D1 radiographic score progressed from D1 to D2. Besides, in the test group, 1 lesion with an E2 radiographic score progressed from E2 to D1 (Fig. 2). No adverse events were reported by the patients either during or after the resin infiltration procedure.

Fig. 2.

Radiographic assessment of caries progression after 1 year among test and control lesions.

Discussion

The resin infiltrant penetrates into the porous enamel [18, 19]. This material blocks the diffusion pathways of cariogenic acids and consequently prevents lesion development. It establishes a barrier within the caries lesion which can reinforce the enamel structure, avoiding or delaying cavitation and disruption of the surface [18, 20].

The results of the present study showed that resin infiltration is a clinically efficacious method for the treatment of interproximal caries. By using the resin infiltration technique, caries progression was found to be significantly reduced after 1 year in the resin infiltrant-applicated group compared with the control group.

Studies evaluating the efficacy of resin infiltration in proximal caries lesions were conducted in children, adolescents, and young adults [11, 16, 21, 22, 23]. In previous studies involving adolescents/young adults and young adults, the average ages were 21 and 25 years, respectively [11, 16, 23]. Similarly, in our study, the average age was just about 21 years. The caries risk of the patients was medium/high as in previous studies [11, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24].

Likewise, resin infiltration was shown to be effective in the prevention of the progression of interface caries in both primary and permanent teeth in other studies [11, 16, 17, 21, 22, 24, 25]. Meyer-Lueckel et al. [11] reported on the 3-year impact of resin infiltration to prevent the progression of proximal non-cavitated caries lesions compared to placebo treatment. Eleven out of 26 control lesions (42%) and 1 out of 26 test lesions (4%) showed progression radiographically. A study conducted by Paris et al. [16] indicated that 10 out of 27 lesions (37%) in the control group and 2 out of 27 lesions (7%) in the test group showed progression after 18 months. Another study evaluated 238 pairs of proximal caries lesions and reported lesion progression recorded in 10 out of 186 test lesions (5%) and in 58 out of 186 control lesions (31%) after 18 months [17]. Ammari et al. [21] observed caries progression in 11.9% (5 out of 42) of the test lesions compared to 33.3% (14 out of 42) of the control lesions. Bagher et al. [22] showed that, from the 25 subjects examined at the 24-month follow-up visit, 10 of the test lesions (40%) showed caries progression while 18 of the control lesions (72%) showed caries progression. A comparative pairwise assessment indicated significantly more progression in control (7) versus infiltration (1) lesions for 32 lesion pairs [24]. Krois et al. [25] indicated that infiltration was more efficacious for arresting early (non-cavitated) proximal lesions than non-invasive treatment after a mean follow-up of 25 months.

In addition, the rate of decay progression for both control (20%) and test groups (2.2%) after 1 year was lower in our study compared to other studies [23, 26]. One of the main reasons could be the higher rates of D1 lesions, given that these are more likely to be cavitated compared with E1 and E2 lesions [27, 28], especially in children with high caries risk [26]. The second reason could be that individualized holders may not be used when the radiograph is taken [26]. In this case, a false positive result may be perceived as caries progression. These reasons may explain the lower rate of caries progression in this and other studies [11, 16, 17, 21].

The results of this study in terms of caries progression were evaluated using DSR, in which to increase the noticeable changes in radiographs, the structured noise is reduced. This technique is very sensitive to any physical noise occurring between the radiographs, and even minor changes lead to large errors in the results [29]. For a successful DSR, reproducible exposure positions and the same contrast and density of the serial radiographs are essential preconditions. Care should be taken to reproduce the same image geometry in follow-up images by using individualized holders to provide a means of accurate comparison of the depth of the lesion. When digital images are made using reproducible geometry, one can be subtracted from the other, resulting in a subtraction image that displays the changes that have occurred between the two examinations [30].

The limitations of this study are the small sample size and short-term clinical follow-up. Another limitation is that patients were not blinded, as a mock treatment was not conducted in the control group.

Conclusion

Based on the data obtained from this study, we suggest that the use of a microinvasive method in the form of the resin infiltration technique is efficacious in arresting carious lesions when compared with non-invasive treatment alone.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the local committee at Erciyes University and informed consent was obtained from each patient. This research was ethically conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Project Unit of Erciyes University (TDH-2015-6060).

References

- 1.Kidd EA, van Amerongen JP. The role of operative treatment. In: Fejerkov O, Kidd E, editors. Dental caries: the disease and its clinical management. Munksgaard. Oxford: Blackwell; 2003. pp. pp.245–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rayapudi J, Usha C. Knowledge, attitude and skills of dental practitioners of Puducherry on minimally invasive dentistry concepts: A questionnaire survey. J Conserv Dent. 2018;21((3)):257–62. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_309_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirsiaghi F, Leung A, Fine P, Blizard R, Louca C. An investigation of general dental practitioners' understanding and perceptions of minimally invasive dentistry. Br Dent J. 2018;225((5)):420–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domejean-Orliaguet S, Tubert-Jeannin S, Riordan PJ, Espelid I, Tveit AB. French dentists' restorative treatment decisions. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2:125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martignon S, Eksrand KR, Ellwood R. Efficacy of sealing proximal early active lesions: an 18-month clinical study evaluated by conventional and subtraction radiography. Caries Res. 2006;40((5)):382–8. doi: 10.1159/000094282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H, Mueller J, Hummel M, Kielbassa AM. Progression of sealed initial bovine enamel lesions under demineralizing conditions in vitro. Caries Res. 2006;40((2)):124–9. doi: 10.1159/000091058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller J, Meyer-Lueckel H, Paris S, Hopfenmuller W, Kielbassa AM. Inhibition of lesion progression by the penetration of resins in vitro: influence of the application procedure. Oper Dent. 2006;1((3)):338–45. doi: 10.2341/05-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domejean S, Ducamp R, Leger S, Holmgren C. Resin infiltration of non-cavitated caries lesions: a systematic review. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:216–21. doi: 10.1159/000371709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatzimarkou S, Koletsi D, Kavvadia K. The effect of resin infiltration on proximal caries lesions in primary and permanent teeth. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Dent. 2018;77:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espelid I, Tveit AB. Cilical and radiographic assessment of approximal carious lesions. Acta Odontol Scand. 1986;44((1)):31–7. doi: 10.3109/00016358609041295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer-Lueckel H, Bitter K, Paris S, Meyer- Lueckel H Bitter K, Paris S: Randomized controlled clinical trial on proximal caries infiltration: Three-year follow-up. Caries Res. 2012;46((6)):544–8. doi: 10.1159/000341807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter HG, Barnes GP. Gingival Bleeding Index. J Periodontol. 1974;45((11)):801–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1974.45.11.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO . Oral health surveys; basic methods. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekstrant KR, Bruun M. Plaque and gingival status as indicators for caries progression on approximal surfaces. Caries Res. 1998;32((1)):41–5. doi: 10.1159/000016428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Axelsson P. Diagnosis and risk prediction of dental caries. Chicago: Quintessence Publisher Co; 2000. pp. pp.151–74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paris S, Hopfenmuller W, Meyer-Luechel H. Resin infiltration of caries lesions: an efficacy randomized trial. J Dent Res. 2010;89((8)):823–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034510369289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer-Lueckel H, Balbach A, Schikowsky C, Bitter K, Paris S. Pragmatic RCT on the efficacy of proximal caries infiltration. J Dent Res. 2016;95((5)):531–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034516629116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paris S, Meyer Lueckel H. Inhibition of caries progression by resin infiltration in situ. Caries Res. 2010;44((1)):47–54. doi: 10.1159/000275917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekstrand KR, Martignon S, Bakhshandeh A, Ricketts DN. The non-operative resin treatment of proximal caries lesions. Dent Update. 2012;39((9)):614–6. doi: 10.12968/denu.2012.39.9.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phark JH. Duartes Jr, Meyer-Lueckel H, Paris S: Caries infiltration with resins: a novel treatment option for interproximal caries. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2009;30:313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ammari MM, Jorge RC, Souza IP, Soviero VM. Efficacy of resin infiltration of proximal caries in primary molars: 1-year follow-up of a split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22((3)):1355–62. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagher SM, Hegazi FM, Finkelman M, Ramesh A, Gowharji N, Swee G, et al. Radio effectiveness of resin Infiltration in arresting insipient proximal enamel lesions in primary molars. Pediatr Dent. 2018;40:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martignon S, Ekstrand KR, Gomez J, Lara JS, Cortes A. Infiltrating sealing proximal caries lesions: a 3-year randomized clinical trial. J Dent Res. 2012;91((3)):288–92. doi: 10.1177/0022034511435328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters MC, Hopkins AR, Jr, Yu Q. Resin infiltration: an effective adjunct strategy for managing high caries risk-A within-person randomized controlled clinical trial. J Dent. 2018;79:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krois J, Göstemeyer G, Reda S, Schwendicke F. Sealing or infiltrating proximal carious lesions. J Dent. 2018;74:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekstrand KR, Bakhshandeh A, Martignon S. Treatment of proximal superficial caries lesions on primary molar teeth with resin infiltration and fluoride varnish versus fluoride varnish only: efficacy after 1 year. Caries Res. 2010;44((1)):41–6. doi: 10.1159/000275573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hintze H, Wenzel A, Danielsen B. Behaviour of approximal carious lesions assessed by clinical examination after tooth separation and radiography: a 2.5-year longitudinal study in young adults. Caries Res. 1999;33((6)):415–22. doi: 10.1159/000016545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mejare I, Stenlund H, Zelenzy-Holmlund C. Caries incidence and lesion progression from adolescence to young adulthood: a prospective 15-year cohort study in Sweden. Caries Res. 2004;38:130–141. doi: 10.1159/000075937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hekmatian E, Sharif S, Khodaeian N. Literature review digital subtraction radiography in dentistry. Dent Res J. 2005;2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.White SC, Pharoah MJ. Oral radiology principles and interpretation. 7th ed. Missouri: Elsevier Mosby; 2014. p. p. 292. [Google Scholar]