Abstract

Background

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) can have considerable effects on employment outcomes because of its disabling character.

Goals

We aimed to investigate the impact of IBD in the workplace and to better understand the need for accommodations and adaptations.

Study

Between November 2017 and March 2018, IBD patients were recruited from outpatient clinics in Christchurch Hospital, New Zealand. The survey assessed employment, the need for workplace accommodations and the difficulty arranging it, insurance, and disability using the item-reduced Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Index for self-report (IBD-DI-SR). Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and multivariate logistic regression modeling.

Results

One hundred twenty-three patients were included (response rate 64%), 112 of whom reported that they experienced symptoms while working (60% female, 71% Crohn's disease, mean age 41.9 years). Ninety-one percent needed at least 1 workplace accommodation when symptoms were most severe. Almost half of the patients who needed an accommodation had difficulty arranging it. The most needed accommodations were time to go to medical appointments (71%) and easy access to a suitable toilet (71%). Being female, having less effective medication, and being distressed were associated with the need for 2 or more accommodations, difficulty in arranging accommodations, and not asking for needed accommodation.

Conclusions

Many IBD patients need accommodations at work while symptomatic in order to overcome workplace disability, which can be difficult to arrange. Improved resources are needed to inform employees and employers about the disease, the possibilities for workplace accommodations, and practical strategies to request them.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, Ulcerative colitis, Employment, Workplace disability

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic disease that causes varying levels of disability in patients. Because of its chronic relapsing and remitting character, IBD impacts patients throughout their lives [1]. Many patients develop IBD at an early age and therefore it can have considerable effects on employment outcomes [2].

New Zealand has one of the highest rates of IBD in the world and the incidence of IBD is increasing [3]. The New Zealand Burden of Disease report projects that the indirect costs will rise because of a decrease in work productivity in patients with IBD. Work productivity is lower, mainly due to time away from work (absenteeism), reduced performance while at work (presenteeism), and loss of employment due to patients downgrading their employment. There is also the future lost productivity due to the impact on schooling, learning abilities, courses, and similar activities [4]. A systematic review analyzing studies on IBD worldwide showed that a lower number of IBD patients were employed or part of the labor force compared to unmatched healthy individuals [5]. The difference became more evident in IBD patients with symptoms when compared with IBD patients without symptoms or controls.

Much research has been undertaken on the impact of IBD on work outcomes, measuring direct and indirect costs, sick leave, and employment status [5]. Even the impact of medical or surgical interventions on work outcomes in IBD patients has been studied [5, 6, 7]. However, a paucity of research has focused on the work experiences of patients with IBD and the methods for overcoming workplace disability.

In a qualitative study of Restall et al. [8], 45 patients with IBD were asked to describe their work experiences. Participants described the impact of IBD on their workplace participation; functioning was affected by different external aspects including workplace culture, acceptance by employers and colleagues, and having a toilet nearby. Finally, the participants stated that workplace participation would be enabled by the facilitation of required accommodations and adaptations, emphasizing the responsibility of the employer in this regard [8].

The recent study of Chhibba et al. [9] supports these findings and concluded that more than 90% of people with IBD need accommodations, although many have difficulty arranging them (11–35% depending on the type of accommodation) or do not ask for them (5–22% depending on the type of accommodation). They also reported that a higher symptom severity was associated with the need for more than 1 accommodation but also not asking for one if needed [9]. Workplace accommodations can be helpful to patients to manage their jobs and therefore stay at work when suffering from an illness.

No research in New Zealand has studied workplace disability in IBD and how to overcome it. This study is one of a number of collaborative international studies aiming to develop a broad understanding of the impact of IBD on the workplace and how this is overcome in a national and international context [9]. A thorough understanding of workplace disability can provide valuable information to improve the employment and participation of people with IBD. Given that there are unique employment services, financial assistance and insurance systems within each country, it is important to study this in New Zealand. Secondary to studying workplace accommodations, we also aimed to report on insurance, loss of income cover, and qualitative aspects regarding employment not captured in the quantitative answers.

Materials and Methods

Participants

In this cross-sectional, observational study, patients were recruited between November 2017 and March 2018 in Christchurch, New Zealand, from the gastroenterology outpatient clinic in Christchurch Hospital, the gastroenterology ward, the medical day unit, and private clinics. IBD patients who were aged 18 years and older, who were or had been employed, and who could speak English and were able to complete the questionnaire were eligible for this study.

Procedure

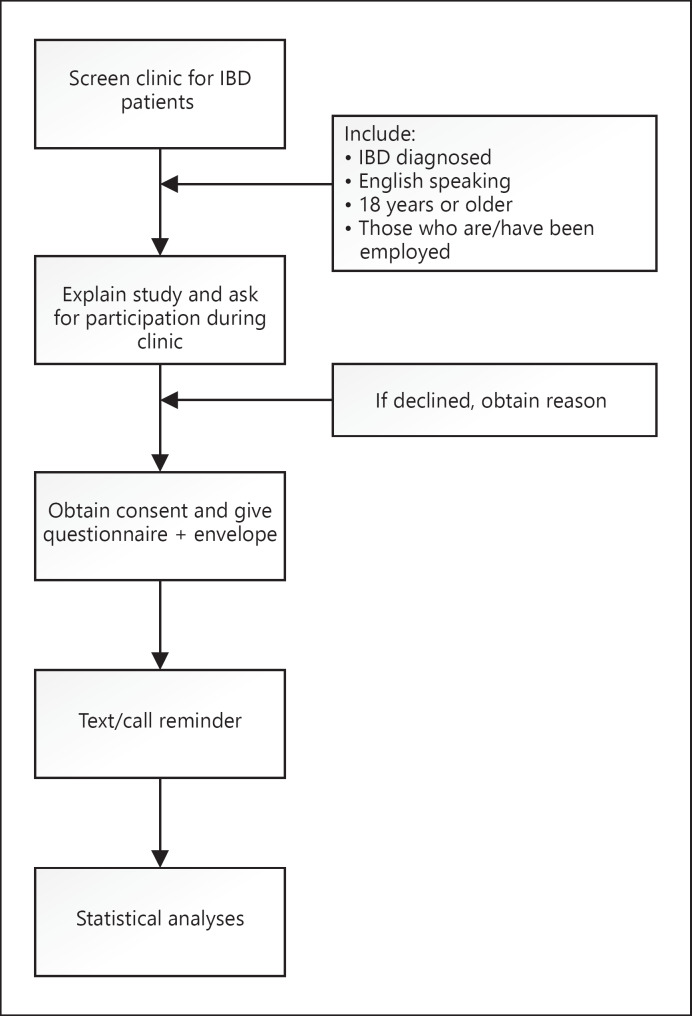

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through this study. Gastroenterology outpatient clinic lists were scanned and patients with IBD were asked after their appointment if they were interested in participating in the research. Consenters received an envelope with the questionnaire, an information sheet, and a consent form. They were requested to send the questionnaire back together with the consent form. For patients who wanted to complete the questionnaire online, there was a link on the questionnaire to the online version using QuestionPro (online survey tool). If patients did not complete the questionnaire within 2 weeks of recruitment, a text message reminder was sent to them. The final method of contact was a phone call after which no further attempts were made to get them to complete it.

Fig. 1.

Flow of participants through this study.

Instruments

Survey Questionnaire

The questionnaire is adapted from a recent Canadian study [9]. Questions were adjusted to the New Zealand healthcare system to optimize the survey. Seven sections were used.

Section A asked about demographic and disease characteristics.

Section B asked about employment, with questions concerning experiences with employment and related activities.

Section C focused on the current work experiences in the workplace in the past month (rated on a 5-point Likert type scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”).

Section D asked about the income coverage for time away from work, with questions concerning insurance or benefits/allowances from the employer or government to cover for days missed at work due to illness.

Section E assessed 7 types of workplace accommodations and adaptations. For each type of accommodation the participants were asked whether they needed it, whether it was available if they needed it, how they tried to arrange the accommodation if needed, and how easy or difficult it was to make this arrangement (rated on a 5-point Likert type scale from “very easy” to “very difficult”).

Section F asked about how the participants had been feeling during the past 30 days. The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale 6-item short form (K6) is a widely used and validated 6-item measure of psychological distress. The K6 includes items assessing symptoms of depression and anxiety over the past 30 days [10].

Section G focused on insurance coverage and the difficulty arranging it.

Section H focused on IBD and health, using the item-reduced Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Index for self-report (IBD-DI-SR) [11]. The IBD-DI is a validated instrument that explores the severity of disability and limitations in different domains [12]. This index is validated for self-report and it was reduced to 8 items. The response for each item on the questionnaire is either dichotomous (“yes” vs. “no”) or ordinal on a 1–5 Likert scale (with 1 being “no difficulty” and 5 being “extreme difficulty”). The overall disability score ranges from −26 (maximum disability) to +6 (no disability) [13].

Open-ended questions allowed patients to give other suggestions for improving the health services and work supports available for persons with IBD and to formulate questions a participant would like to ask an employment law expert in New Zealand.

Statistical Analysis

The power calculation was based on the ability to have a CI of 90%, and therefore a minimum of 120 patients needed to be included. All statistical analyses were undertaken using SPSS v24.0 and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data entry was performed by 2 researchers and cross-checked to eliminate data entry errors.

The statistical analyses involved descriptive statistics to present the demographic characteristics of the survey respondents. Multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess relationships between demographic and disability variables and the variables describing workplace accommodations. OR were used to describe the association between these variables. Three models were used among the respondents who were having IBD symptoms while working, during the period that they were suffering most. Model 1 investigated the correlation of characteristics with the need for at least 2 of 7 accommodations. Model 2 assessed the characteristics associated with difficulty arranging an accommodation. Model 3 evaluated the characteristics that were correlated with not asking for an accommodation. Patients included in multiple regression models 2 and 3 needed at least 1 type of workplace accommodation. Working from home and self-employment were compared to working at an employer's place. Age was categorized into 60 years or older, versus younger. The IBD-SR scores were displayed as a continuous variable. The K6 is divided into “no current emotional distress” with scores under 6 and “distressed” with scores of 6 and higher. Highest education was categorized into the following 4 groups: no education, secondary/high school, tertiary/university, and trade. The most paid and unpaid sick days in 12 months were described with a median because they were not normally distributed.

Results

Patient Characteristics

One hundred ninety-seven patients were approached for this study, and 125 of them completed it (response rate 64.0%). Two patients were excluded due to returning the questionnaire too late or not having work experience; finally, 123 persons were included (59% female, 68% CD, average age 42.5 years [SD 13.5 years]). Of the 123 included patients, 112 reported that they experienced symptoms while working. Those patients were included in a subanalysis, described in Table 1. Looking at the severity of symptoms when they were having the most problems while employed, most patients had severe (38%) or very severe symptoms (30%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants with symptoms while working at paid employment

| Females | 67 (60) |

| CD/UC ratio | 79 (71)/33 (29) |

| Age, years | 41.9±13 |

| New Zealander or European | 111 (99) |

| Workplace when symptoms were most severe (n = 110) | |

| Away from home | 91 (83) |

| Home/self-employed | 19 (17) |

The total number of partipants is 112. Values are presented as means ± SD or numbers (%).

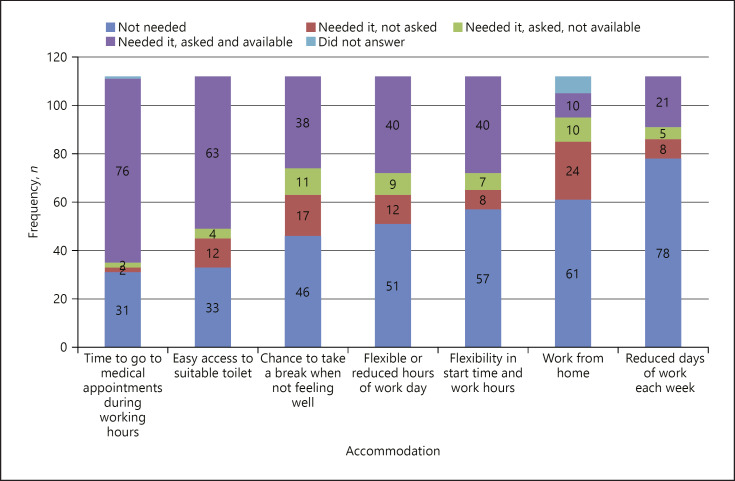

Workplace Accommodation

Figure 2 shows the different accommodations and adaptations needed by patients and how these were managed. Overall, 102 of 112 patients needed at least 1 accommodation (91%). The accommodations needed most were time to go to medical appointments during working hours (71%) and easy access to a suitable toilet (71%). They were followed by a chance to take a break when not feeling well (59%) and flexible or reduced hours of work each day (55%). Fewer people needed flexibility in start time and work hours (49%), work from home (39%), and reduced days of work each week (29%). A proportion of the patients responded that they needed an accommodation but did not ask for it (2–21%). Fewer asked for an accommodation but were told that it was not available (2–10%). Only considering patients who needed the accommodation, this increased to 3–22%. An adaptation was available for the majority of the patients who asked for it (9–68%). Table 2 shows the reasons for reluctance in asking for this needed accommodation.

Fig. 2.

Needs for workplace accommodation and how the needs were managed (n = 112).

Table 2.

Reasons for not asking for needed accommodation

| Accommodation | Work from home (n = 24) | Easy access to a toilet (n = 11) | Medical appointment during work (n = 2) | Flexible/reduced hours per day (n = 11) | Flexible/reduced days per week (n = 7) | Flexible start time or hours (n = 5) | Break when not feeling well (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Seems) not possiblea | 17 | 8 | − | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Work not supportive, or afraid to ask | 1 | 1 | − | 2 | 2 | − | 3 |

| Did not realize I was that sick or that this could help me | 1 | − | − | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Not comfortable asking/embarrassed | 4 | 1 | − | − | − | − | 3 |

| Did not disclose that I had IBD | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Could not afford it | − | − | − | 2 | 3 | − | − |

| Fixed it eventually another wayb | − | − | 2 | 2 | − | 2 | 4 |

Because people estimated that they were not able to carry out their job at home because of the type of work.

Fixed it eventually themselves, e.g., by taking sick leave instead of asking for flexibility or just continuing without taking that needed break.

We asked those who needed an accommodation how this was arranged (Table 3). Most participants took care of it themselves (32–79%) or arranged it informally with their supervisor (10–55%). A few people wrote a request to their employer or arranged it with outside help. Almost half of the patients who needed at least 1 accommodation had difficulty arranging it (48%; 49/102).

Table 3.

Way of arranging accommodations and difficulty arranging them

| Accommodation | N | Took care of it myself | Informal arrangement with supervisor | Written request to employer | Arranged with outside help | Missing | Easy/normal to arrange | Difficult to arrange | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work from home | 44 | 14 (32) | 13 (30) | 1 (2) | 0 | 16 (36) | 13 | 15 | 16 |

| Easy access to a suitable toilet | 79 | 60 (79) | 8 (10) | 0 | 0 | 11 (14) | 58 | 12 | 9 |

| Medical appointments during working hours | 80 | 33 (41) | 44 (55) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 70 | 10 | 0 |

| Flexible or reduced work hours each day | 61 | 20 (33) | 31 (51) | 7 (12) | 0 | 3 (5) | 38 | 19 | 4 |

| Reduced days of work each week | 34 | 14 (44) | 16 (50) | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 | 20 | 13 | 1 |

| Flexibility in start time and work hours | 55 | 20 (36) | 30 (55) | 1 (2) | 0 | 4 (7) | 38 | 14 | 3 |

| A break when not feeling well | 66 | 32 (48) | 26 (39) | 0 | 0 | 8 (12) | 38 | 23 | 5 |

Values are presented as numbers or numbers (%).

Table 4 shows the multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the association between the respondents' characteristics and work experience. A detailed version is available in online supplementary Table 1 (see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000506702 for all online suppl. material). Model 1 shows the characteristics correlated with the need for at least 2 of 7 accommodations during the period that they were having the most symptoms while working. Female sex was associated with the need for 2 or more accommodations (OR = 3.63; 90% CI 1.24–10.58). Model 2 assesses the characteristics of the participants associated with difficulty arranging at least 1 accommodation. The predictive characteristics were: having less effective medication (overall p = 0.03; OR = 3.72; 90% CI 1.41–9.78) and being more distressed at the time of the study (OR = 4.41; 90% CI 1.68–11.57). Model 3 summarizes the respondent characteristics that correlated with not asking for at least 1 needed accommodation. The logistic regression showed that being more distressed at the time of the study was associated with not asking for a needed accommodation (OR = 5.47; 90% CI 2.20–13.60).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression models regarding workplace accommodations

| Variable | Model 1: requiring 2 or more accommodations (n = 112) |

Model 2: difficulty arranging for accommodationa (n = 102) | Model 3: not asking for needed accommodationa(n = 102) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % required | n for models 2 and 3 | % required | % required | |

| Sex | |||||

| Maleb | 45 | 71.1 | 36 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Female | 67 | 91.0e | 66 | 47.0 | 42.4 |

| IBD type | |||||

| CDb | 79 | 87.9 | 71 | 49.3 | 46.5 |

| UC | 33 | 81.0 | 31 | 45.2 | 41.9 |

| Age | |||||

| <60 yearsb | 98 | 83.7 | 90 | 47.8 | 45.6 |

| ≥60 years | 14 | 78.6 | 12 | 50.0 | 41.7 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/living as marriedb | 66 | 81.8 | 43 | 44.1 | 35.6 |

| Other | 46 | 84.8 | 59 | 53.5 | 58.1d |

| Hospitalized | |||||

| Nob | 27 | 74.1 | 26 | 38.5 | 46.2 |

| Yes | 85 | 85.9 | 76 | 51.3 | 44.70 |

| Surgery | |||||

| Nob | 66 | 81.8 | 61 | 47.5 | 45.9 |

| Yes | 46 | 84.8 | 41 | 48.8 | 43.9 |

| Effectiveness of medication | Overalle | ||||

| None | 8 | 100 | 8 | 62.5 | 62.5 |

| Somewhat | 45 | 84.4 | 41 | 65.9e | 56.1d |

| Highb | 56 | 78.6 | 50 | 30.0 | 34.0 |

| Side effects | |||||

| Nob | 80 | 82.5 | 73 | 42.5 | 38.4 |

| Yes | 29 | 82.8 | 26 | 61.5 | 65.4d |

| Highest education | Overalld | ||||

| Noneb | 7 | 71.4 | 7 | 42.9 | 28.6 |

| 2nd | 33 | 78.8 | 32 | 43.8 | 40.6 |

| 3rd | 51 | 94.1 | 48 | 56.3 | 52.1 |

| Trade | 17 | 64.7 | 12 | 33.3 | 41.7 |

| Active job | |||||

| <50% activeb | 54 | 85.2 | 49 | 49.0 | 40.8 |

| >50% active | 50 | 80.0 | 45 | 46.7 | 51.1 |

| Symptom severity | |||||

| Mild/moderateb | 36 | 77.8 | 34 | 35.3 | 35.3 |

| Severe/very severe | 76 | 85.5 | 68 | 54.4 | 50.0 |

| Workplace | |||||

| Away from homeb | 91 | 86.6 | 87 | 51.7 | 48.3 |

| Home/self-employed | 19 | 68.4 | 13 | 23.1 | 15.4d |

| K6 score (distress) | |||||

| <6b | 67 | 83.6 | 60 | 31.7 | 26.7 |

| ≥6 | 44 | 81.8 | 41 | 70.7e | 70.7e |

| IBD-DI-SRc | N/A | Not significant | N/A | 0.89 | 0.89 (0.82–0.96)d |

| (0.82–0.97)d | |||||

Models 2 and 3 had IBD-DI-SR as a continuous variable which was significant in bivariate analyses but not in multivariate analyses in both models.

Reference category.

Treated as a continuous variable so no percentages are reported.

Significant in the bivariate model.

Remained significant in the multivariate model.

As shown in online supplementary Table 2, eighteen percent of the patients had difficulty arranging life insurance because of their condition. This was almost the same for arranging income protection insurance (17%). A government benefit because of the disability affecting their ability to work was claimed by 14% of the respondents, with almost half receiving it (47%) [14].

Half of the respondents who were currently employed agreed that in the past month the stresses of their job were much harder to handle because of their disease (Table 5). Almost half (49%) were distracted from taking pleasure in work because of their IBD. A third (33%) of the patients did not feel energetic enough to complete all of their work.

Table 5.

Work experiences of persons in the past month

| Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Uncertain | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree | Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Because of, or despite, my inflammatory bowel disease … | ||||||

| The stresses of my job were much harder to handle | 32 (29) | 16 (14) | 7 (6) | 45 (40) | 11 (10) | 1 (1) |

| I was able to finish hard tasks in my work | 7 (6) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 29 (26) | 69 (62) | 1 (1) |

| I was distracted from taking pleasure in work | 35 (31) | 20 (18) | 3 (3) | 45 (40) | 8 (7) | 1 (1) |

| I felt hopeless about finishing certain work tasks | 60 (54) | 18 (16) | 5 (5) | 22 (20) | 6 (5) | 1 (1) |

| I was able to focus on achieving my goals at work | 9 (8) | 6 (5) | 6 (5) | 41 (37) | 49 (44) | 1 (1) |

| I felt energetic enough to complete all of my work | 13 (12) | 23 (21) | 2 (2) | 47 (42) | 26 (23) | 1 (1) |

The total number of participants was 112. Values are presented as numbers (%).

Fifty-eight persons answered at least 1 of 3 open-ended question. These answers are shown in online supplementary Table 3. Common themes throughout the answers included access (or lack thereof) to health services, their mental state, and access to toilet facilities.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a broad understanding of the impact of IBD on the workplace and how this is overcome in New Zealand. This study shows that 91% of the respondents needed at least 1 accommodation during the time of their worst symptoms and 83% needed at least 2 of the 7 adaptations listed. Almost half of the patients who needed an accommodation had difficulty arranging it. The accommodation needed most was time to go to medical appointments during working hours and easy access to a suitable toilet. Most persons took care of it themselves, or arranged it informally with their supervisor. These results are consistent with the collaborative international study in Canada [9].

Model 1 of the logistic regression showed a significant association between female sex and the need for 2 or more accommodations. While it is possible that this difference could be the extra family-related responsibilities of many females relative to males fueling the higher need for adaptations, it is important to note that a recent published meta-analysis investigating the relationship between gender and work-family conflict found little difference between men and women managing the work-family interface [15]. No reasons for these gender differences should be assumed without further research.

Less effective medication and being more distressed at the time of the study predicted difficulty arranging an accommodation. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, recall bias may have led to inaccurate recollection of previous events. The emotional distress questionnaire gives information about the current situation, not about the distress at the time when symptoms were most impactful. However, it is plausible that there is a direct association between having trouble arranging accommodations in the past and being distressed in the present because people with adverse past experiences (including troubles in the workplace) are more likely to be distressed at the present time. However, the question of whether present distress is associated with difficulties arranging present accommodations is not answered by this study. Meanwhile, the association between less effective medication and difficulty arranging an accommodation is more difficult to explain given that symptom severity is not associated with the ability to arrange an accommodation.

Model 3 showed that being more distressed at the time of the study was associated with not asking for a needed accommodation. Of note was that reasons for reluctance to ask may worsen emotional distress, for example if the workplace is not supportive, when asking for an adaptation is embarrassing or if the person cannot afford to work fewer hours. Hence, it is plausible that the factors driving reluctance to ask for accommodations are the same factors driving emotional distress. Similar factors could also be driving the corresponding relationship in Model 2.

In New Zealand, there are different types of financial support for people who are unable to work due to an injury or sickness. When it is trauma related, New Zealand residents are eligible to receive means-related income from the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC). Successful claimants can get 80% of their income covered by the ACC. Residents with a chronic illness, on the other hand, can try to apply for a government benefit based on income, but this is less than the amount from the ACC and is not indexed to the person's income. People can get loss of income insurance privately but this is less common. These different ways of support, depending on the origin of the disability, can have socioeconomic consequences [16]. Besides this, the number of sick days available for a New Zealand employee depends on the company terms. This underlines the importance of being able to stay at work by making use of accommodations and adaptations.

We asked respondents open-ended questions including other suggestions for improving health services and work support available for persons with IBD. One respondent underlined the importance of overcoming workplace disability and contributing to the society: “Getting out of the depression and hopelessness I felt for the first year or so of being very unwell with IBD has been very much down to the positive effects of contributing to society through work − albeit unpaid at the moment. So I actually recommend that even though an IBD sufferer might feel that they cannot work and cannot see any future for their good health − I have found work to almost be a cure for my IBD.”

A limitation mentioned in earlier research is ignorance of the reasons for reluctance in asking for needed accommodations and adaptations [9]. Table 2 shows that some patients are not comfortable asking for an adaptation or are even embarrassed. Furthermore, respondents mentioned that their work is not supportive or that they were afraid to even ask. This demonstrates the relevance of improved resources to inform employees and employers about the disease, possibilities for workplace accommodations, and practical strategies to request them [17, 18].

Limitations and Future Research

Our study has several limitations. We recruited patients from the outpatient and private clinic, medical day unit and ward. Patients attending the outpatient clinic are mostly patients who come for a routine follow-up appointment but also people who have increasing symptoms or problems with their IBD. Therefore, this population could possibly be sicker than the broader New Zealand IBD population.

The response rate was moderate but not excellent, perhaps due to the somewhat lengthy nature of the questionnaire. However, the sample size was adequate regarding our power calculation, but some models from the multiple regression model contained smaller groups which may have led to underpowering.

As noted in Table 3 there were missing values for the question concerning how patients arranged an accommodation. Nevertheless, a clear trend was shown towards managing it themselves or with a little help from their supervisors. Also, there were missing values for the question that asked about the difficulty of arranging an accommodation for patients who stated that they needed an accommodation but did not ask for it. Interpreting these missing answers looking at the corresponding open answers did not change model 2. An explanation for the missing values could be that if the respondent did not ask for a needed accommodation, it is in some situations hard to say something about the difficulty of arranging it.

There is no answer available for patients with stomas to the question about the number of liquid or very soft stools in the IBD-DI-SR, as described in earlier research. The scoring system needs to be updated to allow investigation of the association between disability and the needs for accommodations for patients who have a stoma [11].

Patients who were unemployed or did not have work experience yet because of IBD were not included in this study. During recruitment, those patients stated that while graduated they were not confident enough about their IBD to apply for a job and start working. In future research it is important to focus on young patients who are about to enter the workforce as well. Though briefly alluded to in this study, the role of colleagues in supporting a person with IBD is also a relevant subject which should be investigated in further research, as was pointed out by participants (online suppl. Table 3).

Conclusion

In summary, many symptomatic IBD patients need accommodations to overcome workplace disability and this can be difficult to arrange. Patients who are female, have less effective medication and are distressed are in greater need of support. Improved resources are needed to inform employees and employers about the disease, the possibilities for workplace accommodations, and practical strategies to request them.

Statement of Ethics

The subjects gave their written informed consent. Ethical approval was received by the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (reference 17/CEN/5/196). Locality approval was also granted by the Canterbury District Health Board (RO#17164) and Te Komiti Whakarite.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Bernstein is supported in part by the Bingham Chair in Gastroenterology. He serves on advisory boards for Abbvie Canada, Janssen Canada, Shire Canada, Takeda Canada, Pfizer, and Ferring Canada and has consulted to Mylan Pharmaceuticals and 4-D Pharma. He has received educational grants from Abbvie Canada, Pfizer Canada, Shire Canada, Takeda Canada, and Janssen Canada and is on the speaker's panel for Ferring Canada and Shire Canada. For the remaining authors no conflict of interests exists.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this study.

Author Contributions

E.P.: significant involvement in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and drafting. C.D.: significant involvement in data collection, drafting, and approval of the final version of this paper for publication. C.F.: significant involvement in the study design, data analysis, and approval of the final version of this paper for publication. R.B.G.: significant involvement in the study design, data collection, and approval of the final version of this paper for publication. T.E.: significant involvement in data collection and approval of the final version of this paper for publication. N.K.H.B.: significant involvement in the study design, drafting, and approval of the final version of this paper for publication. C.N.B.: significant involvement in the study design and approval of the final version of this paper for publication. A.M.M.: significant involvement in the study design, data collection, data analysis, drafting, and approval of the final version of this paper for publication.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

References

- 1.El-Matary W, Dufault B, Moroz SP, Schellenberg J, Bernstein CN. Education, Employment, Income, and Marital Status Among Adults Diagnosed With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases During Childhood or Adolescence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Apr;15((4)):518–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.09.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zand A, van Deen WK, Inserra EK, Hall L, Kane E, Centeno A, et al. Presenteeism in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Hidden Problem with Significant Economic Impact. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Jul;21((7)):1623–30. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su HY, Gupta V, Day AS, Gearry RB. Rising Incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canterbury, New Zealand. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Sep;22((9)):2238–44. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahui S, Snively S, Ternent M. Crohn's, Colitis New Zealand S Reducing the Growing Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in New Zealand. Crohn's & Colitis New Zealand; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Büsch K, da Silva SA, Holton M, Rabacow FM, Khalili H, Ludvigsson JF. Sick leave and disability pension in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Crohn's Colitis. 2014 Nov;8((11)):1362–77. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binion DG, Louis E, Oldenburg B, Mulani P, Bensimon AG, Yang M, et al. Effect of adalimumab on work productivity and indirect costs in moderate to severe Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;25((9)):492–6. doi: 10.1155/2011/938194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neovius M, Arkema EV, Blomqvist P, Ekbom A, Smedby KE. Patients with ulcerative colitis miss more days of work than the general population, even following colectomy. Gastroenterology. 2013 Mar;144((3)):536–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Restall GJ, Simms AM, Walker JR, Graff LA, Sexton KA, Rogala L, et al. Understanding Work Experiences of People with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jul;22((7)):1688–97. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chhibba T, Walker JR, Sexton K, Restall G, Ivekovic M, Shafer LA, et al. Workplace Accommodation for Persons With IBD: What Is Needed and What Is Accessed. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Oct;15((10)):1589–95 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Feb;60((2)):184–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulides E, Kim C, Frampton C, Gearry RB, Eglinton T, Leong RW, et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index for self-report and development of an item-reduced version. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;34((1)):92–102. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gower-Rousseau C, Sarter H, Savoye G, Tavernier N, Fumery M, Sandborn WJ, et al. International Programme to Develop New Indexes for Crohn's Disease (IPNIC) group. International Programme to Develop New Indexes for Crohn's Disease (IPNIC) group Validation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Index in a population-based cohort. Gut. 2017 Apr;66((4)):588–96. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leong RW, Huang T, Ko Y, Jeon A, Chang J, Kohler F, et al. Prospective validation study of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health score in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. J Crohn's Colitis. 2014 Oct;8((10)):1237–45. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New Zealand Government Benefits and payments [Internet] 2019. Available from: https://www.workandincome.govt.nz/

- 15.Shockley KM, Shen W, DeNunzio MM, Arvan ML, Knudsen EA. Disentangling the relationship between gender and work-family conflict: an integration of theoretical perspectives using meta-analytic methods. J Appl Psychol. 2017 Dec;102((12)):1601–35. doi: 10.1037/apl0000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.New Zealand Government ACC [Internet] 2019. Available from: https://www.acc.co.nz/

- 17.Gay M, et al. Crohn's, Colitis and Employment - from Career Aspirations to Reality. Hertfordshire: Crohn's and Colitis UK; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulides E, Gearry RB, de Boer NK, Mulder CJ, Bernstein CN, McCombie AM. Accommodations and Adaptations to Overcome Workplace Disability in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Systematic Review. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2019 Feb;3((3)):138–44. doi: 10.1159/000495293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data