Summary

In randomized clinical trials, the primary outcome, Y, often requires long-term follow-up and/or is costly to measure. For such settings, it is desirable to use a surrogate marker, S, to infer the treatment effect on Y, Δ. Identifying such an S and quantifying the proportion of treatment effect on Y explained by the effect on S are thus of great importance. Most existing methods for quantifying the proportion of treatment effect are model based and may yield biased estimates under model misspecification. Recently proposed nonparametric methods require strong assumptions to ensure that the proportion of treatment effect is in the range [0, 1]. Additionally, optimal use of S to approximate Δ is especially important when S relates to Y nonlinearly. In this paper we identify an optimal transformation of S, gopt(·), such that the proportion of treatment effect explained can be inferred based on gopt(S). In addition, we provide two novel model-free definitions of proportion of treatment effect explained and simple conditions for ensuring that it lies within [0, 1]. We provide nonparametric estimation procedures and establish asymptotic properties of the proposed estimators. Simulation studies demonstrate that the proposed methods perform well in finite samples. We illustrate the proposed procedures using a randomized study of HIV patients.

Keywords: Nonparametric estimation, Proportion of treatment effect explained, Randomized clinical trial, Surrogate marker

1. Introduction

When a new treatment or prevention strategy becomes available, randomized clinical trials are often conducted to compare its efficacy to a placebo or standard care. Such trials, however, are complex and costly to perform (DiMasi et al., 2010). To ensure the efficient and timely arrival of new and affordable interventions, it is thus crucial to explore effective approaches to randomized clinical trial design (Food and Drug Administration, 2004). One key challenge is that the primary outcomes of many clinical trials are often expensive to measure and/or require long-term follow-up of patients. This gives rise to an increasing interest in identifying and validating surrogate markers that can be used instead to infer treatment effect on the primary outcome. Using such surrogate endpoints can be cost effective and can reduce participant burden if the true target clinical endpoint is invasive or difficult to measure.

The potential advantages of using a surrogate endpoint as a substitute for a primary endpoint have led to a considerable number of statistical methods for evaluating the validity of surrogate endpoints. Prentice (1989) proposed a seminal framework for evaluating the validity of a surrogate via hypothesis testing. A surrogate endpoint is considered as valid only if a test for treatment effect on the surrogate endpoint is also a valid test for treatment effect on the primary outcome. Shifting the focus from testing to estimation, Freedman et al. (1992) considered estimating the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate, by assessing the change in the magnitude of the treatment effect estimate when a surrogate is added to a specified regression model. Lin et al. (1997) subsequently proposed a proportion of treatment effect explained measure for failure time endpoints using a time-dependent Cox proportional hazards model. The validity of the proportion of treatment effect explained estimates from these methods relies heavily on the validity of the specified regression models with and without the surrogate marker, yet these two sets of models often do not hold simultaneously (Lin et al., 1997). In addition to the proportion of treatment effect explained, other quantities and criteria for validating a surrogate biomarker have been proposed, though they are also largely model based (Robins & Greenland, 1992; Buyse & Molenberghs, 1998; Ghosh, 2008, 2009; Huang & Gilbert, 2011; Conlon et al., 2017). Wang & Taylor (2002) proposed a more flexible approach to quantifying the proportion of treatment effect explained, by examining what the treatment effect would have been if the surrogate had identical distributions among the treatment groups. Their approach still requires modelling choices. Based on the proportion of treatment effect explained definition of Wang & Taylor (2002), Parast et al. (2016) proposed a fully nonparametric model-free estimation procedure. However, both Wang & Taylor (2002) and Parast et al. (2016) require additional assumptions, for example that the relationship between the surrogate and the primary outcome is monotone, which is needed to ensure that the proportion of treatment effect explained quantity is between 0 and 1. In addition, Parast et al. (2016) requires that the support of the surrogate biomarker distribution is the same in the treatment and control groups. While often reasonable, these assumptions may not hold for some practical settings, and as such the proportion of treatment effect explained estimates from these methods may be biased and beyond the range of [0, 1].

In this paper we propose a novel approach to quantifying the proportion of treatment effect explained by a potential surrogate marker, S, by first identifying an optimal transformation of S, S → gopt(S), such that gopt(S) achieves the lowest mean squared prediction error for the outcome Y. With gopt(·) obtained, we define the proportion of treatment effect explained by quantifying how well gopt(S) can be used to infer the true treatment effect on Y. One could argue that this framework, i.e., directly trying to find a function of the surrogate that approximates the primary outcome, is conceptually more in line with the ultimate goal of surrogate biomarker identification, namely, to eventually replace the primary outcome. We propose two proportion of treatment effect explained definitions based on gopt(S), pte1 and pte2, with pte1 being the ratio between the treatment effect on gopt(S) and the treatment effect on Y, and pte2 quantifying how well the subject-level treatment effect on Y can be approximated by the effect on gopt(S). We show that pte1 corresponds to the quantity considered in Parast et al. (2016) under a specific choice of the reference distribution required by their method, while pte2 has the advantage of always being between 0 and 1.We also provide nonparametric inference procedures for these proportion of treatment effect explained measures and derive their theoretical properties. Simulation results suggest that the proposed estimators perform well compared to existing methods.

2. Optimal transformation and proportion of treatment effect explained definition

2.1. Setting and notation

Let Y be the primary outcome and S the surrogate marker. The outcome Y may be discrete or continuous, and the biomarker S may be discrete or continuous. Throughout we treat S as continuous, but when S is discrete, either ordinal or categorical, all derivations and theoretical results remain valid with density functions replaced by probability mass functions. Let A be the treatment indicator, with A = 1 denoting the treated group and A = 0 denoting the control group; we assume the treatment is randomly assigned to the patients at baseline. We use the standard causal inference framework to define {Y(a),S(a)} as the potential outcome and surrogate marker under treatment A = a. In practice, (Y(1), S(1)) and (Y(0), S(0)) cannot be observed simultaneously for an individual. We assume that the data for analysis consist of n independent and identically distributed random variables {Di = (Yi, Si, Ai), i = 1, …, n} and P(Ai = 1) = p1 ∈ (0, 1), where and . Without loss of generality, we assume that p1 = 0.5 and discuss the estimation adjustment for p1 ╪ 0.5 in the discussion section. Throughout, the treatment effect on Y is defined as

and without loss of generality we assume that Δ ⩾ 0.

2.2. Optimal function of the surrogate biomarker

Our goal is to find an optimal function of S, gopt(·), such that gopt(S) can be used to approximate the primary outcome and subsequently to quantify the treatment effect on Y, where the same gopt(·) is applied to both treatment arms. Price et al. (2018) also recently proposed the idea of finding the optimal function of a potential surrogate. Their proposed approach identifies the optimal transformation of the surrogate for each treatment group separately; that is, the optimal functions are different depending on the treatment group. Our aim is different in that we aim to identify a single optimal function of S that can be used regardless of the treatment group. We translate our problem of interest into a prediction framework and aim to identify gopt(·) that minimizes the mean squared error loss function

Unfortunately, since (Y(1), S(1)) and (Y(0), S(0)) cannot be observed simultaneously at the individual level and the correlations between (Y(1), S(1)) and (Y(0), S(0)) are not identifiable, we instead aim to minimize the above squared loss under a working independence assumption:

| (1) |

which leads to

Under (1), E[{Y(1)−g(S(1))}{Y(0)−g(S(0))}] can be simplified to E{Y(1)−g(S(1))}E{Y(0)−g(S(0))}. Furthermore, since gopt(·) is only identifiable up to a constant shift, we define the optimal g, denoted by gopt(s), as the following constrained minimizer:

| (2) |

where is the class of measurable functions. Admittedly, it may be unlikely for (1) to hold in practice. However, this assumption is only used to facilitate the derivation gopt(·) and is not required for the interpretation of our proposed proportion of treatment effect explained measure nor for the validity of the associated inference procedures. Even when this assumption is violated, the derived gopt(·) may still be a sensible choice for transforming the surrogate marker. We provide additional comments on the implications of violations of this working assumption in §6.

In the Supplementary Material we show that under (1) the optimal function gopt(·) can be expressed as

where

and Fa(s) are the respective density and cumulative distribution functions of , and

Thus, the optimal transformation is the conditional mean function of Y given S, shifted by a scaled posterior probability function of A = 0 given S. When the treatment has no effect on the conditional expectation of Y on S, i.e., the treatment effect is completely through s, then λ = 0 and gopt(s) reduces to gopt(s) = E(Y | S = s) = m(s).

With gopt(·) identified such that gopt(S) optimally approximates Y, we may infer the treatment effect on Y based on the treatment effect on gopt(S). This highlights a major advantage of such a framework (Price et al., 2018), which enables us to not only perform testing on the treatment effect using S, but also to directly use the treatment effect on gopt(S), defined as

to approximate the target treatment effect Δ = E{Y(1) − Y(0)}, which is the best approximation based on the surrogate marker alone. Price et al. (2018) also proposed this idea to estimate the treatment effect on the primary outcome based on the treatment effect on the transformed surrogate, though their proposed transformation is treatment specific.

2.3. Model-free definitions of the proportion of treatment effect explained

To quantify the proportion of treatment effect explained by S, a natural definition is

Although pte1 is derived from a very different perspective, it directly relates to the proportion of treatment effect explained quantity defined by Wang & Taylor (2002) and Parast et al. (2016),

where is some reference function which was suggested as chosen to be either F0 or F1 in Parast et al. (2016), though is not restricted to be a distribution function. In the Supplementary Material we show that pte1 corresponds to pteL when one chooses , which is a subdistribution function. Thus, our proposed gopt(·) and essentially provide a mechanism for selecting an optimal reference function in the previously proposed definition of pteL.

Our proposed framework has an advantage in that it allows us to relax some assumptions that are required not only by Wang & Taylor (2002) and Parast et al. (2016), but by other surrogate marker work in general. For example, Parast et al. (2016) requires that:

Condition 1. P(S ⩾ s | A = 1) > P(S ⩾ s | A = 0) for all s;

Condition 2. m1(s) > m0(s) for all s;

Condition 3. m1(s) is a nondecreasing function in s;

Condition 4. S(1) and S(0) have the same support.

These conditions are imposed to ensure their proposed proportion of treatment effect explained is between 0 and 1, but can easily fail when the supports of S(0) and S(1) are not the same. To ensure that pte1 is between 0 and 1, we show in the Supplementary Material that we can relax Conditions 1–4 of Parast et al. (2016) and only need to assume:

Condition 5. for all u;

Condition 6. for all u in the common support of gopt(S(1)) and gopt(S(0)), where and for a = 0, 1.

Thus, our method requires neither monotonicity nor the same surrogate support. In the Supplementary Material we show that under Conditions 5 and 6 , indicating that Δ = 0 would imply . Hence, using to infer Δ will not result in a surrogate paradox situation, defined as a situation in which the treatment effect on the surrogate marker is positive and the surrogate marker is positively correlated with the primary outcome, but the treatment effect on the primary outcome is negative.

An alternative approach to define the proportion of treatment effect explained based on gopt(S) is to frame this as the percentage of variation in Y(1)−Y(0) explained by the variation in gopt(S(1))−gopt(S(0)). The second definition for the proportion of treatment effect explained by gopt(·) that we propose is based on assessing how much of the variation in Y(1) − Y(0) is explained by gopt(S(1)) − gopt(S(0)) under our working assumption of (Y(1),S(1)) ⊥ (Y(0),S(0)). Specifically, we define the proportion of treatment effect explained as

where and , for i ╪ j. Here, MSEnull represents the variation of under the null of S being completely uninformative of Y. As with pte1, we expect pte2 to be close to 1 if gopt(S) is a good surrogate, and close to 0 if gopt(S) is a useless surrogate. By the definition of gopt(·), we know that . Therefore, pte2 is guaranteed to be between 0 and 1.

Though pte2 has some advantages over pte1, one important benefit of pte1 is the interpretability of the quantity and the appeal of such an interpretation to clinicians and applied researchers. Both pte1 and pteL can be described as the proportion of the treatment effect on the primary outcome that is captured by the treatment effect on the surrogate marker, or the transformation of the surrogate marker. In addition to being a very intuitive concept, the pte1 formulation also directly allows us to approximate Δ based on for future studies, where the primary outcome Y is not measured.

3. Nonparametric estimation of pte1 and pte2

In this section we propose nonparametric estimation procedures for the optimal transformation function gopt(s), as well as for the resulting proportion of treatment effect explained parameters. Noting that gopt(s) involves , m(s) and λ, we propose to first estimate these quantities nonparametrically via standard kernel smoothing. Specifically, we let

where Kh(·) = K(·/h)/h, K(·) is a symmetric kernel function, the bandwidth h = O(n−ν) with ν ∈ (1/5, 1/2), and . When S is discrete, the above kernel estimators can be simplified by replacing Kh(Si − s) with I (Si = s). Subsequently, we estimate gopt(s) as

Since both and are standard kernel density and conditional mean estimators, it is straightforward to show that is a uniformly consistent estimator of gopt(s) under mild regularity conditions given in the Supplementary Material. In addition, we show in the Supplementary Material that converges in distribution to a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance σ2(s).

With gopt estimated as , we can construct plug-in estimates for as , where

Therefore, we estimate pte1 as , where . Similarly, we may estimate pte2 as ,

In the Supplementary Material we show that and are consistent estimators of pte1 and pte2, respectively. Furthermore, when h = O(n−ν) with and , respectively, converge in distribution to and , where and are defined in the Supplementary Material. The normal approximation holds for when pte2 ∈ (0, 1). In practice, we may estimate and by empirically estimating the influence functions or via resampling similar to those employed in Parast et al. (2016). For resampling, we may generate V = (V1, …, Vn) from independent and identically distributed nonnegative random variables with mean 1 and variance 1 such as the unit exponential distribution. For each set of V, we let ,

Then we may obtain the perturbed counterparts of , , , and as

where ,

In practice, we may generate a large number, say B, of realizations for V, and then obtain B realizations of , , , and . The variance estimation and the confidence interval can be constructed based on the empirical variances and quantiles of these realizations. We expect that resampling-based inference is particularly appealing for , which involves empirical mean square error estimates that tend to have a skewed distribution in finite samples. When the surrogate marker carries little information about the outcome, and may be greater than in finite samples. In such a case, we simply let . When pte2 ≈ 0, the aforementioned normal approximation for the proposed estimator may be poor, although the distribution of can still be approximated well by a multivariate normal distribution. In such a case, the resampling method can still provide a valid but potentially conservative confidence interval for pte2 based on the empirical quantile of .

4. Simulation studies

We first conducted simulation studies to evaluate the finite-sample performance of our methods along with several existing methods, including (i) Parast et al. (2016), denoted as pteL; (ii) Wang & Taylor (2002), denoted as pteW; and (iii) Freedman et al. (1992), denoted as pteF. Across all configurations we let n = 500, 1000, 250 and 500 in each arm respectively, and chose K(·) as a Gaussian kernel with bandwidth , c0 = 0.11, where hopt is found using the method of Scott (1992).Variances were estimated using the proposed resampling method with B = 1000. All results were summarized based on 500 simulated datasets for each configuration.

We consider four data generation scenarios. For settings k = 1, 2, 3, 4, we generate

where E(0) and E(1) follow the unit exponential distribution, and we let , , , , , , , , , , , , ; , , , . All assumptions required by Parast et al. (2016) are satisfied under setting 1, but S(0) and S(1) have rather different supports under setting 2 and the effect of S on Y is nonmonotone under settings 3 and 4. Assumption (1) holds in all four settings.

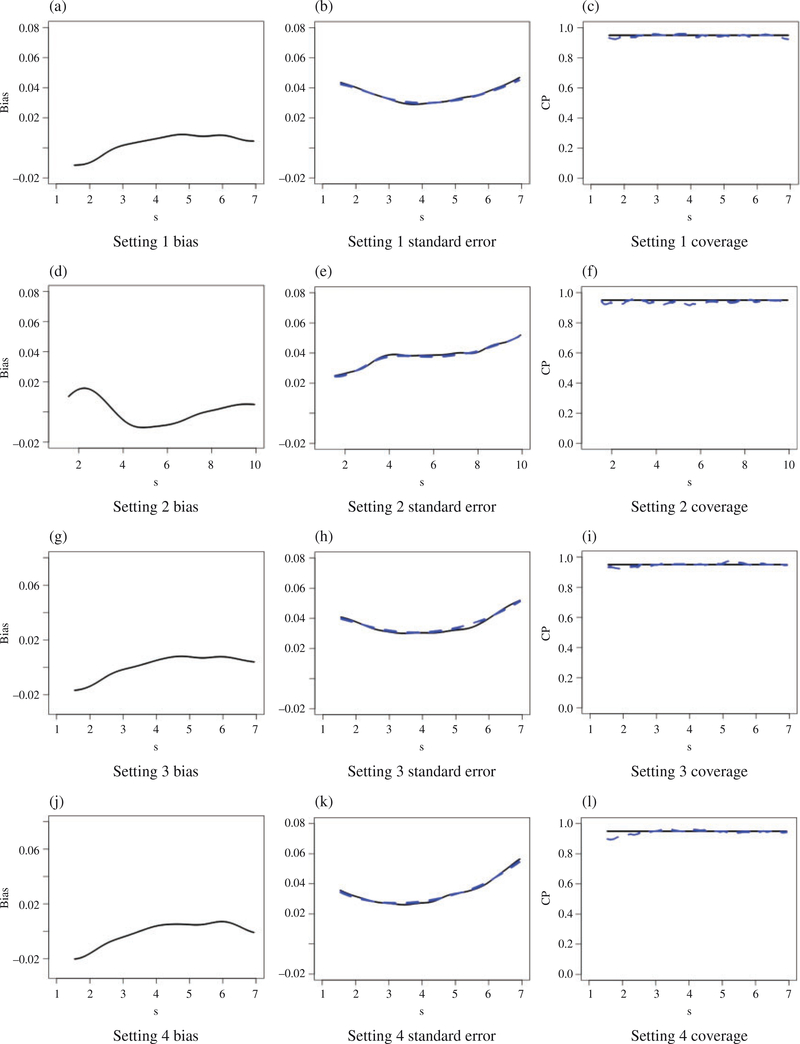

Figure 1 shows the empirical biases, empirical standard errors, the average of the estimated standard errors and the empirical coverage probabilities of the 95% pointwise confidence intervals for gopt(·) when n = 1000. The estimation results of pte1 and pte2 when n = 1000 are shown in Table 1. The results for the estimation of gopt(·), pte1 and pte2 when n = 500 have similar patterns, as shown in the Supplementary Material. Across all settings, the point estimates for gopt(·), pte1 and pte2 present negligible biases, and the estimated standard errors are close to the empirical standard errors. The coverage probabilities of the confidence intervals are also close to their nominal level.

Fig. 1.

The empirical bias, empirical standard error (solid) versus the average of the estimated standard error (dashed), coverage probabilities (dashed) of the 95% (solid) confidence intervals for when n = 1000.

Table 1.

Estimates of pte1, pte2, pteL, pteW and pteF along with their empirical standard errors under settings 1, 2, 3 and 4 with n = 1000. For our proposed proportion of treatment effect explained estimates, we also present the average of the estimate standard errors (shown in subscript) along with the empirical coverage probabilities of the 95% confidence intervals

| n = 1000 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | pteL | pteW | pteF | ||||||||

| True | Est | ESEASE | CP | Est | ESE | Est | ESE | Est | ESE | ||

| 1 | pte1 | 0.614 | 0.616 | 0.0830.078 | 0.938 | 0.470 | 0.136 | 0.198 | 0.067 | 0.193 | 0.064 |

| pte2 | 0.418 | 0.423 | 0.0270.026 | 0.942 | |||||||

| 2 | pte1 | 0.442 | 0.439 | 0.0340.034 | 0.942 | −0.265 | 0.056 | −0.365 | 0.066 | −0.218 | 0.040 |

| pte2 | 0.383 | 0.394 | 0.0270.028 | 0.934 | |||||||

| 3 | pte1 | 0.511 | 0.503 | 0.0800.081 | 0.954 | 0.281 | 0.135 | 0.192 | 0.065 | 0.194 | 0.065 |

| pte2 | 0.362 | 0.367 | 0.0280.026 | 0.934 | |||||||

| 4 | pte1 | 0.318 | 0.316 | 0.0880.084 | 0.936 | −0.033 | 0.142 | 0.184 | 0.068 | 0.194 | 0.071 |

| pte2 | 0.322 | 0.331 | 0.0270.026 | 0.930 | |||||||

Est, estimates; ESE, empirical standard errors; ASE, average of the estimate standard errors; CP, coverage probability.

Table 1 also summarizes the results of other proportion of treatment effect explained estimators. Across all settings, the Wang & Taylor (2002) and Freedman et al. (1992) methods misspecify the underlying model. As a result, pteW and pteF estimates differ substantially from the nonparametric estimates from pte1, pte2 and pteL. In setting 2, pteW, pteF and pteL all fail with their estimates being negative. This is because the assumptions in these papers are not satisfied. For example, the supports of the treatment and control groups are different. However, the proposed proportion of treatment effect explained definitions and corresponding estimates do not have such a problem here. For setting 3, where we have introduced a mild deviation from the monotone increasing assumption, similar conclusions to setting 1 can be drawn. For setting 4, we observe that, except for our proposed proportion of treatment effect explained estimates, all existing methods yield proportion of treatment effect explained estimates close to zero. This is due to the fact that E(Y | S = s) is quite nonmonotone in this case, and our proposed estimates evaluate the proportion of treatment effect explained for gopt(S) rather than S. These results highlight the robustness of our proposed method and the corresponding nonparametric estimation procedure.

We performed further sensitivity analyses for the proposed procedures when the working assumption (1) fails to hold. We consider two general settings: (I) Y(1) ⊥ Y(0) | (S(1), S(0)), but S(1) and S(0) are correlated; (II) (S(0), S(1), Y(0), Y(1)) have varying degrees of correlation and Y(1) ⊥ Y(0) | (S(1), S(0)) may not hold. Under setting I with the conditional independence structure it is still feasible to derive , although goracle has a complex form and is the solution to an integral equation, as shown in the Supplementary Material. In setting I two cases are considered, corresponding to a unimodal goracle and a monotone goracle, respectively. Specifically, in the first case, Ia, we generated

We then generated Y(1) and Y(0) from

resulting in a unimodal goracle. In setting Ib,

resulting in a monotone goracle. In setting II, we generated

resulting in nine different correlation combinations. Under setting II with the more general correlation structure, goracle is no longer tractable and hence we only examine the validity of the proposed nonparametric estimation procedures under the violation of (1).

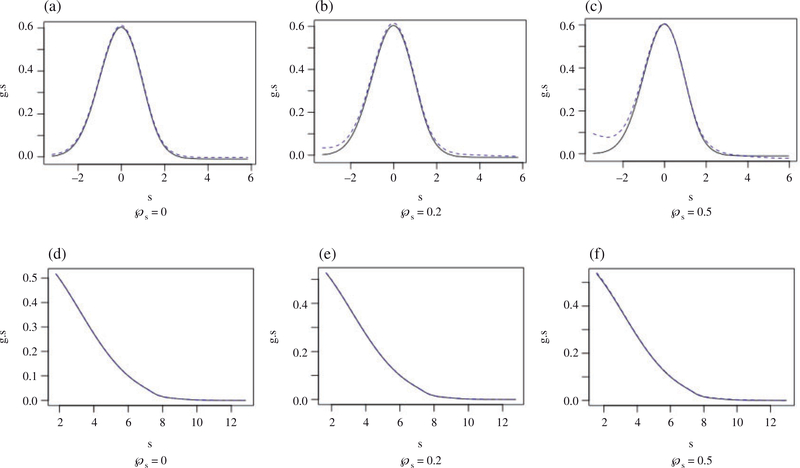

For setting I, we compare the true goracle to our proposed gopt and the proportion of treatment effect explained obtained under the two transformations. As shown in Fig. 2, goracle and gopt mostly coincide with each other except for the extreme tail parts for setting Ia when goracle is unimodal. For setting Ib, where goracle is monotone, the two functions are nearly identical to each other. Thus, gopt remains a good approximation to goracle even when the independence assumption is violated. In Table 2 we present the proportion of treatment effect explained estimates obtained using goracle and using gopt. The two sets of estimates are close to each other, suggesting that the proportion of treatment effect explained estimates are not very sensitive to these departures from the working independence assumption.

Fig. 2.

The solid line denotes the proposed optimal gopt(s) and the dotted line denotes the true optimal goracle(s) by solving the integration function considering from setting Ia, panels (a), (b) and (c), where goracle is unimodal, and Ib, panels (d), (e) and (f), where goracle is monotone.

Table 2.

Estimates of pte1, pte2 derived using goracle versus the proposed gopt from settings Ia and Ib when Y(1) ⊥ Y(0) | (S(1), S(0)) and S(1) and S(0) are multivariate normal with correlation

| Ia | Ib | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| goracle(·) | gopt(·) | goracle(·) | gopt(·) | ||

| 0 | pte1 | 0.935 | 0.935 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| pte2 | 0.682 | 0.683 | 0.504 | 0.504 | |

| 0.2 | pte1 | 0.926 | 0.929 | 0.995 | 0.994 |

| pte2 | 0.677 | 0.679 | 0.504 | 0.504 | |

| 0.5 | pte1 | 0.939 | 0.949 | 0.992 | 0.992 |

| pte2 | 0.670 | 0.670 | 0.503 | 0.503 | |

Simulation results for setting II are summarized in Table 3, where we compare the point estimates of pte1 and pte2 to their corresponding limiting values based on gopt and examine the validity of the standard error estimates. Across the nine combinations of and , and have negligible bias and the average estimated standard errors are close to the empirical standard errors. These results confirm that the proposed inference procedure is valid regardless of whether the working independence assumption holds.

Table 3.

Estimates of pte1 and pte2 compared with the population values along with their empirical standard errors under nine variations of setting II with varying values of and for n = 500. Also shown are the average of the estimated standard errors along with the empirical coverage probabilities of the 95% confidence intervals

| Truth | Est | ESE | ASE | CP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pte1 | 0.887 | 0.885 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.942 | ||

| pte2 | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.916 | ||

| pte1 | 0.887 | 0.885 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.944 | ||

| pte2 | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.904 | ||

| pte1 | 0.882 | 0.879 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.946 | ||

| pte2 | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.900 | ||

| pte1 | 0.887 | 0.885 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.946 | ||

| pte2 | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.916 | ||

| pte1 | 0.887 | 0.884 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.936 | ||

| pte2 | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.914 | ||

| pte1 | 0.877 | 0.874 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.934 | ||

| pte2 | 0.951 | 0.953 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.902 | ||

| pte1 | 0.882 | 0.879 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.924 | ||

| pte2 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.916 | ||

| pte1 | 0.877 | 0.874 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.920 | ||

| pte2 | 0.952 | 0.952 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.914 | ||

| pte1 | 0.868 | 0.866 | 0.018 | 0.017 | 0.930 | ||

| pte2 | 0.941 | 0.942 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.906 |

Est, estimates; ESE, empirical standard errors; ASE, average of the estimate standard errors; CP, coverage probability.

5. Application

5.1. Setting

We applied the proposed procedure to evaluate the surrogacy of CD4 counts in predicting the treatment effect on plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations using the AIDS Clinical Trials Group, ACTG, 320 Study (Hammer et al., 1997), as the suppression of plasma RNA has been accepted and is widely used as a surrogate for progression to AIDS/death in the literature. The ACTG 320 study was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial that compared the three-drug regimen of indinavir, zidovudine or stavudine, and lamivudine with the two-drug regimen of zidovudine or stavudine, and lamivudine in HIV-infected patients with at least three months of prior zidovudine therapy. A total of 1156 patients were randomly assigned to one of the two regimens. Outcomes of interest for this study included time to a new AIDS-defining event, changes in CD4 counts and RNA concentrations. While HIV-1 viral quantification is essential for treatment monitoring, measuring RNA concentration is relatively expensive, especially for resource-limited countries (Calmy et al., 2007). We investigate whether CD4 counts can effectively serve as a surrogate marker for RNA outcomes. Specifically, we aim to evaluate the proportion of the treatment effect on RNA viral load explained by the treatment effect on S = CD424−0, defined as the change in CD4 counts from baseline to week 24. The ranges of S in the two treatment arms are [−100, 733.5] in the combination therapy and [−136.5, 277] in the triple therapy arm. We considered two RNA outcomes: the reduction in log10RNA from baseline to week 24, denoted by , and the binary outcome of attaining RNA below 500 at week 24, denoted by . The analysis focused on 830 patients, 418 in triple therapy and 412 in combination therapy, who had complete information on CD4 and RNA measurements.

5.2. Optimal function of S and proportion of treatment effect explained estimates

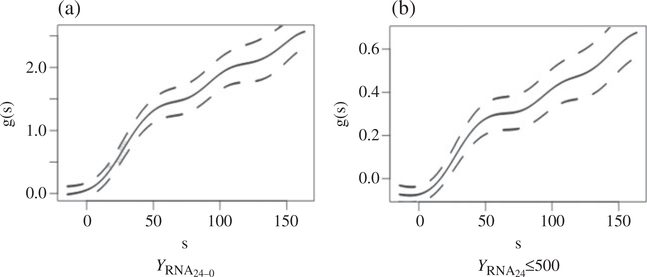

We first applied the proposed methods to examine gopt(·) of the surrogate CD424−0 for predicting the treatment response as quantified by the RNA viral load. The estimated gopt(·) for and along with their pointwise confidence intervals are shown in Figs. 3(a) and (b). For both outcomes, the transformation function appears to be slightly nonlinear with a slightly larger magnitude of slope for smaller values of CD424−0. The treatment effect on the RNA outcomes and on the surrogate outcomes are all highly significant. For , the treatment effect is estimated as , SE = 0.083, while the treatment effect on the predicted outcome based on gopt(S) is estimated as , SE = 0.076. This leads to pte1 estimated as 56.8% with 95% confidence interval [49.9%, 63.6%], and pte2 estimated as 65.6% with 95% confidence interval [61.3%, 69.9%]. The estimated pte1 is higher than the estimated pteL of Parast et al. (2016), which was 41.5% with 95% confidence interval [32.3%, 50.7%]. This could be due in part to the slightly non-overlapping distribution of S within the two treatment groups, as shown in the Supplementary Material, which is a required assumption for pteL to be valid. We observe similar patterns for the binary outcome . The estimated pte1 and pte2 were 50.5% with 95% confidence interval [43.2%, 57.8%] and 56.0% with 95% confidence interval [50.9%, 61.1%], respectively. The pte1 estimate is again substantially higher than the pteL estimate of 31.3% with 95% confidence interval [21.7%, 40.9%].

Fig. 3.

Point estimates for the transformation function gopt(·) (solid lines) along with their pointwise 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines) for (a) , the decrease in log10RNA from baseline to week 24, and (b) , the binary outcome of attaining RNA below 500 at week 24.

5.3. Transportability investigation

The overall goal of this work, and surrogate marker research in general, is to identify an S, or function of S as in this paper, that can be used to replace the primary outcome to test for a treatment effect. To actually achieve this goal, certain assumptions would be necessary to ensure that S or the function of S is appropriate for a future study, which we will refer to as transportability. Transportability, the assumptions required for transportability, and how to assess whether those assumptions hold are interesting problems and warrant further work. Here, the interesting structure of the ACTG 320 trial recruitment allows us to empirically explore, just within this application, this concept of transportability.

Since the recruitment for this study was stratified on CD40, we partition the trial into two sub-studies, denoted by and , with different CD40 distributions, to investigate the transportability of the CD4 surrogacy and treatment effect across different study populations. We may treat as a current study and as a separate future study, and investigate the transportability of the proportion of treatment effect explained between these two studies. We consider three different partitioning mechanisms: (i) a completely random partition; (ii) randomly assigning patients with CD40 < 200 into group with probability expit(0.5 − 0.1CD40/smax), and otherwise, but those with CD40 200 always remaining in group ; (iii) randomly assigning patients with CD40 < 100 into group with probability expit(0.5 − 0.2CD40/smax), and otherwise, but those with CD40 100 always remaining in group , where smax is the observed maximum value of CD40. We repeated the partitioning process 40 times for each mechanism and averaged all estimates over the 40 partitions. The average number of patients in group was approximately 415, 454 and 586 for settings i, ii and iii, respectively. The patient populations of and were similar in setting i, with median CD40 of approximately 72.4 in and 70.4 in . In setting ii, the median CD40 was 81.4 in and 59.8 in . The difference between the two studies is more pronounced in setting iii, with the median CD40 being 109.4 in and 30.8 in . For each dataset, we first obtained estimates of and the proportion of treatment effect explained within and within separately. To examine the cross-study transportability, we also assessed the treatment effects on and in group , where and are the estimated gopt(·) using data in and in , respectively.

We report the average treatment effects and proportion of treatment effect explained estimates in Table 2 of the Supplementary Material. In setting I, the two groups are drawn from the same patient population. As expected, the estimates of Δ and as well as the proportion of treatment effect explained estimates from study are comparable to those from study . In addition, the predicted treatment effect based on and based on for those in are also close to each other, indicating that if were an earlier study, one could use data in to estimate gopt as and predict treatment response based on in . In setting II, the two groups have slightly different populations, with group representing patients with lower baseline CD4 counts. We see that the three pte1 estimates are close, potentially indicating that it would still be appropriate to use the estimate of derived using to make inference about Δ in study . In setting III, the baseline CD4 counts in study are substantially lower than in study . The three pte1 estimates differ more than the previous settings, but not substantially. Thus, making inference about Δ in study based on , though not ideal, may be relatively reasonable. These results demonstrate that the transportability of the proposed method may work well for studies with moderately different distributions of baseline CD4, but would require caution when the distributions are quite different.

6. Discussion

Throughout, we assumed that p1 = 0.5 both in the population loss function and in the observed data. In practice, even if the observed trial has a randomization ratio different from 1:1, the proposed loss function is still an appropriate choice as it reflects a future population with p1 = 0.5. In that case, the population gopt(·) remains the same and our proposed estimators can be easily modified to include inverse probability of treatment assignment weights to yield consistent estimators of gopt(·), pte1 and pte2. More generally, if there is a preconceived p1 ╪ 0.5, one may modify both the objective function and the estimators with weights to allow for different treatment assignment probabilities.

Our proposed plug-in estimators for the proportion of treatment effect explained use the same data to estimate both gopt and the proportion of treatment effect explained given g, and hence may suffer from overfitting bias. In our numerical studies, the bias appears negligible compared to the standard error. When the sample size is small, it may be necessary to correct for the overfitting bias, which can be achieved via cross validation by estimating gopt and the proportion of treatment effect explained given g using separate data. In the HIV example, we performed sensitivity analyses considering the cross-study transportability issue, where gopt may be estimated from a previous study and used to derive the treatment effect on the transformed surrogate outcome in a subsequent study. In our opinion, transportability is unavoidable in studying surrogate markers. We choose to assume the transportability of gopt and the proportion of treatment effect explained instead of, for example, the complete joint distribution of outcome and surrogate marker to enhance the robustness of the approach. While these assumptions may still be violated in practice, the results based on the aforementioned simulations and numerical experiments are promising.

In principle, the proposed gopt can still be used even if the treatment effect is measured by a relative risk contrast. We have E(Y(0)) = E{gopt(S(0))}, and

which guarantees the validity of the surrogate marker after transformation, i.e., . In general, if the contrast g(μ1, μ0) used to measure the treatment effect is monotone increasing in μ1 for any fixed μ0, we can guarantee that g{E(Y(1)), E(Y(0))} >= g[E{gopt(S(1))}, E{gopt(S(0))}]. The pte1 can also be generalized as

However, if the treatment effect is not measured by a contrast between μ1 and μ0, such as hazard ratio, the current proposal is not directly applicable.

The proposed proportion of treatment effect explained measures and the associated inference procedures are robust against the violation of the working independence assumption (1), which is mainly used to derive the specific form of gopt(·). We employ this independence assumption because the correlation structure of the counterfactuals is not identifiable, and minimizing is often not analytically or numerically tractable, even if the correlation structure is given. As demonstrated in the Supplementary Material, even under a simple multivariate normal setting, goracle involves solving complex integral equations and depends on the level of correlation, which is not identifiable. However, the correspondence between pte1 and pteL proposed in Parast et al. (2016) does not at all require (1) to hold. As confirmed in the simulation studies, even if (1) fails, the estimation procedures based on , and are valid for making inference about the population values of gopt(s), pte1 and pte2 with gopt(s) defined as (2). In addition, the simulation results suggest that our proposed gopt(·) and proportion of treatment effect explained estimates are not very sensitive to the violation of this assumption. Lastly, even if this working independence assumption is severely violated, gopt(·) can still be viewed as an optimal transformation for the surrogate marker to recover the difference in the primary outcome between two independent patients assigned to treatment and control arms, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The data from the ACTG 320 study used in this paper are publicly available upon request from the AIDS Clinical Trial Group.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available at Biometrika online includes proofs and additional simulations. R code for implementing the proposed procedures is available at https://celehs.github.io/OptimalSurrogate/.

Contributor Information

XUAN WANG, School of Mathematical Sciences, Zhejiang University, 866Yuhangtang Rd., Hangzhou 310027, Zhejiang, China.

LAYLA PARAST, Statistics Group, RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, Santa Monica, California 90401, U.S.A..

LU TIAN, Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 150 Governor’s Lane, Stanford, California 94305, U.S.A..

TIANXI CAI, Department of Biostatistics, Harvard University, 655 Huntington Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, U.S.A..

References

- Buyse M & Molenberghs G (1998). Criteria for the validation of surrogate endpoints in randomized experiments. Biometrics 54, 1014–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmy A, Ford N, Hirschel B, Reynolds SJ, Lynen L, Goemaere E, de la Vega FG, Perrin L & Rodriguez W (2007). HIV viral load monitoring in resource-limited regions: optional or necessary? Clin. Inf. Dis. 44, 128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon A, Taylor J & Elliott M (2017). Surrogacy assessment using principal stratification and a Gaussian copula model. Statist. Meth. Med. Res. 26, 88–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMasi JA, Feldman L, Seckler A & Wilson A (2010).Trends in risks associated with new drug development: success rates for investigational drugs. Clin. Pharm. Therapeut. 87, 272–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration (2004). Challenge and opportunity on the critical path to new medical products. http://www.fda.gov/oc/initiatives/criticalpath/whitepaper.html.

- Freedman LS, Graubard BI & Schatzkin A (1992). Statistical validation of intermediate endpoints for chronic diseases. Statist. Med. 11, 167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D (2008). Semiparametric inference for surrogate endpoints with bivariate censored data. Biometrics 64, 149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D (2009). On assessing surrogacy in a single trial setting using a semicompeting risks paradigm. Biometrics 65, 521–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, Grimes JM, Demeter LM, Currier JS, Eron JR JJ, Feinberg JE, Balfour HH Jr, Deyton LR et al. (1997). A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. New Engl. J. Med. 337, 725–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y & Gilbert PB (2011). Comparing biomarkers as principal surrogate endpoints. Biometrics 67, 1442–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Fleming T & De Gruttola V (1997). Estimating the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Statist. Med. 16, 1515–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parast L, McDermott MM & Tian L (2016). Robust estimation of the proportion of treatment effect explained by surrogate marker information. Statist. Med. 35, 1637–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice RL (1989). Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: definition and operational criteria. Statist. Med. 8, 431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price BL, Gilbert PB & van der Laan MJ (2018). Estimation of the optimal surrogate based on a randomized trial. Biometrics 74, 1271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM & Greenland S (1992). Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology 3, 143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D (1992). Multivariate Density Estimation. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y & Taylor JM (2002). A measure of the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Biometrics 58, 803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.