Questions

-

1Which one of the following is the most likely diagnosis in the case seen in Figure 16-1 ?

-

aMiliary tuberculosis.

-

bSquamous cell carcinoma.

-

cMelanoma.

-

dSilicosis.

-

eBronchopneumonia.

-

a

-

2Referring to Figure 16-2 , the combination of hilar adenopathy and multifocal ill-defined opacities is most consistent with which one of the following?

-

aWegener's granulomatosis.

-

bSarcoidosis.

-

cHypersensitivity pneumonitis.

-

dLangerhans’ cell histiocytosis.

-

eChoriocarcinoma.

-

a

-

3The presence of an air bronchogram throughout a large, irregular opacity is inconsistent with which one of the following diagnoses?

-

aSilicosis.

-

bBronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma.

-

cLymphoma.

-

dWegener's granulomatosis.

-

eSarcoidosis.

-

a

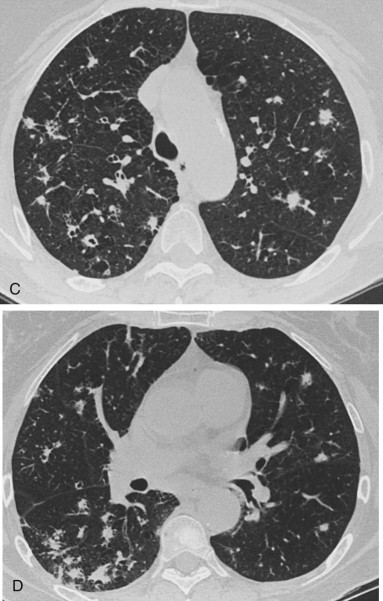

Figure 16-1.

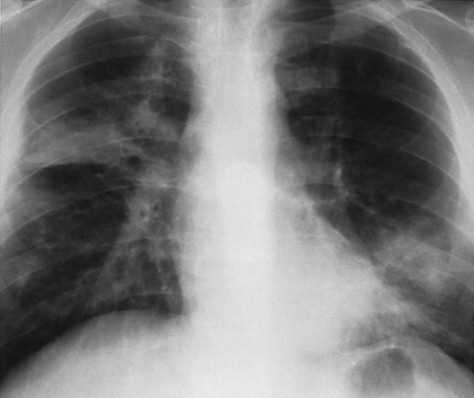

Figure 16-2.

Discussion

Multifocal ill-defined opacities result from a great variety of diffuse pulmonary diseases (Chart 16-1). This pattern is sometimes referred to as a patchy alveolar pattern, but it should be contrasted with the bilaterally symmetric, diffuse coalescing opacities described as the classic appearance of air-space disease in Chapter 15. Many of the entities that cause multifocal ill-defined opacities do result in air-space filling,460 but they also may involve the bronchovascular and septal interstitium. Acute diseases may present as patchy, scattered opacities and progress to complete diffuse air-space consolidation. Some of the additional signs of air-space disease are also encountered in this pattern, including air bronchograms, air alveolograms, and a tendency to be labile. Because many of the entities considered in the differential are in fact primarily interstitial diseases, complete examination of the film may reveal an underlying fine nodular or reticular pattern. Distinction of this multifocal pattern from the fine nodular pattern may also become somewhat of a problem because the definition of the opacities is one of the primary distinguishing characteristics of the two patterns. The description for miliary nodules usually requires that the opacities be sharply defined, in contrast to the less-defined opacities currently under consideration. Also, most entities considered in this differential more typically produce opacities in the range of 1 to 2 or even 3 cm in diameter, in contrast to the fine nodular pattern in which the opacities tend to be less than 5 mm in diameter. Additionally, this pattern may result from diseases that cause multiple, larger nodules and masses. Some tumors may be locally invasive and appear ill-defined because of their growth pattern, whereas others may develop complications such as hemorrhage. Because the differential for multifocal ill-defined opacities is lengthy, its identification obligates the radiologist to review available serial films, carefully evaluate the clinical background of the patient, and recommend additional procedures. When the disease is minimal or the pattern cannot be characterized from the plain film, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) (Figs 16-3, A-C ) may define the pattern, reveal the distribution of the disease, and sometimes suggest a specific diagnosis.

Chart 16-1. Multifocal Ill-Defined Opacities.

-

IInflammatory

-

ABronchopneumonia160 (Staphylococcus, 239 Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, Legionella, 634 Klebsiella, Hemophilus influenzae, 553 Escherichia coli, other gram-negative bacteria, Nocardia 35,190,64035190640)

-

BFungal pneumonia (histoplasmosis,127 blastomycosis,580 candidiases,78 actinomycosis,32,12132121 coccidioidomycosis, aspergillosis,63,74463744 cryptococcosis306,639306639 mucormycosis,41 sporotrichosis119)

-

CTuberculosis53,262,504,80153262504801

-

DSarcoidosis592

-

ELangerhans’ cell histiocytosis1,4981498 (also known as eosinophilic granuloma)

-

FEosinophilic pneumonitis113,234,452113234452 (idiopathic drug reaction626 and secondary to parasites458)

-

GViral125,495,752125495752 and mycoplasma pneumonias219,338219338

-

HRocky Mountain spotted fever437,458,475437458475

-

IPneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (also known as PCP)669

-

JParagonimiasis541

-

KQ fever499

-

LAtypical mycobacteria in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)474

-

MSevere acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)534

-

A

-

IIVascular

-

AThromboemboli314

-

BSeptic emboli290

-

CVasculitis (Wegener's granulomatosis3,227,4273227427 and variants, including lymphomatoid granulomatosis451,453,581451453581 and systemic lupus erythematosis569)

-

DInfectious vasculitis (mucormycosis, aspergillosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever)

-

EGoodpasture's syndrome324,569,665324569665

-

FScleroderma21

-

A

-

IIINeoplastic

-

ABronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma8,57,503,589857503589

-

BLymphoma (Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's)23,33,6142333614

-

CMetastasis (vascular tumors, malignant hemangiomas, choriocarcinoma,447 adenocarcinoma671)

-

DKaposi's sarcoma in patients with AIDS282,528,691282528691

-

EWaldenström's macroglobulinemia589

-

FAngioblastic lymphadenopathy386

-

GMycosis fungoides354,472354472

-

HAmyloid tumors329,734329734

-

IPosttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder157

-

A

-

IVIdiopathic

-

ALymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP)194

-

BDesquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP)90,415,51890415518

-

CIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (rare cause of this pattern)235,521235521

-

DNonspecific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP)464

-

EAcute interstitial pneumonitis (AIP)11,46411464

-

FCryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP; also known as bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia [BOOP])115,132,433,523115132433523

-

A

-

VEnvironmental

-

AHypersensitivity pneumonitis (allergic alveolitis)115,393,558,715,720115393558715720

-

BSilicosis

-

A

-

VIOther

-

ADrug reactions73,551,562,63573551562635

-

BRadiation reactions550,629550629

-

CMetastatic pulmonary calcification (secondary to hypercalcemia)305

-

A

Figure 16-3.

A, Patterns are difficult to characterize in patients with minimal diffuse disease. This coned view of the right lung shows poorly defined, increased opacity that resembles minimal air-space opacity. B, HRCT section of the upper lobes in this patient with sarcoidosis demonstrates multifocal areas of poorly defined, ground-glass opacity with associated reticular opacities. C, HRCT section through the lung bases confirms relative sparing of the lower lobes, which is a common distribution for sarcoidosis.

Inflammatory Diseases

Bacterial Bronchopneumonia

The characteristic pattern of a bronchopneumonia is that of lobular consolidations (see Fig 16-1). Because this type of infection spreads via the tracheobronchial tree, it almost always produces a multilobular pattern. These lobular opacities317 tend to be ill-defined because the fluid and inflammatory exudate that produce the opacities spread through the interstitial planes in addition to spilling into the alveolar spaces.314 In some cases, the lobular pattern may have sharply defined borders where the exudate abuts an interlobular septum. The size of the radiologic opacities depends on the number of contiguous lobules involved. Intervening, normal lobules lead to a very heterogeneous appearance, which Heitzman described as a “patchwork quilt.” If this pattern of multifocal opacities progresses, the consolidations will begin to coalesce and form a pattern of multilobar air-space consolidation (Fig 16-4 ) that may become indistinguishable from the diffuse confluent pattern commonly associated with alveolar edema.

Figure 16-4.

Bilateral, multifocal areas of consolidation caused by bronchopneumonia often progress with large areas of multilobar involvement. This patient has bilateral, lower-lobe consolidations with multiple smaller foci of pneumonia in the upper lobes. As the infection spreads this appearance of multilobar pneumonia may become more uniform and even resemble pulmonary edema.

Knowing the pathogenesis of bronchopneumonia is important for understanding this pattern. In bronchopneumonia, the primary sites of injury are the terminal and respiratory bronchioles. The disease starts as an acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis. The large bronchi undergo epithelial destruction and infiltration of their walls by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Epithelial destruction results in ulcerations that are covered with a fibrinopurulent membrane and that contain large quantities of multiplying organisms. With the more aggressive organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas, a necrotic bronchitis and bronchiolitis lead to thrombosis of lobular branches of the small pulmonary arteries. When this becomes extensive, the multifocal opacities may begin to cavitate (see Chapter 24). As the inflammatory reaction spreads through the walls of the bronchioles to involve the alveolar walls, there is an exudation of fluid and inflammatory cells into the acinus. This results in the pattern of multifocal lobular consolidations described in the preceding paragraph. Thus, bronchopneumonia (lobular pneumonia) is in fact a combination of interstitial and alveolar disease. The injury starts in the airways, involves the bronchovascular bundle, and finally spills into the alveoli, which in later stages may contain edema fluid, blood, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, hyaline membranes, and organisms.

The radiologic pattern of bronchopneumonia is determined by the virulence of the organism and the host's defenses. A mild bronchopneumonia in a noncompromised host may lead only to peribronchial inflammatory infiltration with the radiologic appearance of peribronchial thickening and increased markings. Itoh et al.355 demonstrated that this peribronchial infiltrate may account for the radiologic appearance of diffuse, small (i.e., 5-mm), fluffy, or ill-defined nodules that are very similar to the pattern of acinar consolidation. As indicated earlier, these nodules differ from the expected appearance of miliary nodules mainly in their lack of definition, or fluffy borders. In most cases of bronchopneumonia, this small nodular pattern is transient and rapidly replaced by the more characteristic lobular pattern, with opacities measuring 1 to 2 cm in diameter. As noted in Chapter 15, patients with bronchopneumonia occasionally have only one lobe predominantly involved, but there are almost always other areas of involvement. This is a common pattern for hospital-acquired pneumonias.160 An unusually virulent organism or failure of the patient's immune response leads to rapid enlargement of the multifocal opacities and finally to diffuse air-space consolidations. This has been observed in patients infected by common organisms553 and those infected with unusual organisms, including those with Legionnaires’ disease and Pittsburgh-agent pneumonia.406,564406564

Viral Pneumonia

The spread of viral infections in the respiratory tract has many similarities to bacterial bronchopneumonia. Most viruses produce their effect in the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, leading to tracheitis, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis.389 There is also necrosis of much of the bronchial mucus gland epithelium. The bronchial and bronchiolar walls become very edematous, congested, and infiltrated with lymphocytes. The bronchial infiltrate may extend into the surrounding peribronchial tissues, which become swollen. This infiltrate spreads into the septal tissues of the lung, leading to a diffuse, interstitial, mononuclear, cellular infiltrate. The changes in the airways may extend to the alveolar ducts, but most severe changes occur proximal to the terminal bronchioles. The adjacent alveolar cells, both type-1 and type-2, become swollen and detached. These surfaces then become covered with hyaline membranes. In fulminant cases, there are additional changes in the alveoli. The alveoli are filled with a mixture of blood, edema, fibrin, and macrophages. In the most severely affected areas, there is focal necrosis of the alveolar walls and thrombosis of the alveolar capillaries, leading to necrosis and hemorrhage.

As in bronchopneumonia, the radiologic pattern of a viral pneumonia depends on both the virulence of the organism and the host defenses.69,706970 The mildest cases of viral infection of the airways are confined to the upper airways and manifest no radiologic abnormality. The earliest radiologic abnormalities are the signs of bronchitis and bronchiolitis, which may include peribronchial thickening and signs of air trapping. When the infection spreads into the septal tissues, a reticular pattern with interlobular septal lines, as described in Chapter 18, may result. The more serious cases lead to hemorrhagic edema and areas of air-space consolidation. These opacities may be small and appear as a fine nodular pattern similar to that described in Chapter 17, but the nodules tend to be less well defined than the classic miliary pattern. As the process spreads, areas of lobular consolidation develop, as in bacterial bronchopneumonia. In the most severe cases, these areas of lobular consolidation may coalesce into an extensive diffuse consolidation resembling pulmonary edema or diffuse bacterial bronchopneumonia.

Influenza viral pneumonia should be suspected in patients with typical influenza symptoms of fever, dry cough, headache, myalgia, and prostration. As the infection spreads to the lower respiratory tract, the patient notices an increased production of sputum that may be associated with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, or both. Physical examination reveals rales that may be accompanied by either diminished or harsh breath sounds. Because of the bronchial involvement, wheezes are occasionally noted. The radiologic patterns evolve from a minimal reticular pattern to small, ill-defined nodules to lobular consolidations and finally diffuse confluent opacities. Influenza pneumonia accounts for most influenza mortalities. The most severe cases may be further complicated by adult respiratory distress syndrome or superimposed bacterial pneumonia. At this time, laboratory examination of the sputum and blood becomes paramount to rule out a superimposed bacterial bronchopneumonia. The organisms most likely to present a superimposed bacterial infection are pneumococci, staphylococci, streptococci, and Haemophilus influenzae. In this clinical setting, the development of a superimposed cavitary lesion virtually confirms a superimposed bacterial infection. Other viruses that may cause pneumonia in patients with normal immunity include hanta viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, and adenoviruses.389

The more fulminating cases of viral pneumonia are rarely encountered in normal patients, but are seen in patients with suppressed immune systems including those receiving high-dose, steroid therapy; patients receiving chemotherapy; patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS); organ transplant patients; pregnant women; and the elderly. Herpes simplex, varicella, rubeola, cytomegaloviruses, and adenoviruses occur mainly in immunocompromised patients.389

Varicella pneumonia characteristically occurs from 2 to 5 days after the onset of the typical rash. It is most commonly noted in infants, pregnant women, and adults with altered immunity. Approximately 10% of adult patients may have some degree of pulmonary involvement. In contrast to the situation in bacterial pneumonias, sputum examination shows a predominance of mononuclear cells and giant cells in which type-A intranuclear inclusion bodies may be seen on Giemsa stain. As in the consideration of other viral pneumonias, the possibility of superimposed bacterial infection is best excluded by laboratory examination of sputum and blood. Because the viruses of herpes zoster and varicella are identical, patients with an atypical herpetic syndrome consisting of a rash related to a dermatome and dermatomic distribution of pain are also at an increased risk for development of this type of pneumonia.

Rubeola (measles) pneumonia may be more difficult to diagnose by clinical criteria because the pneumonia occasionally precedes the development of the rash. As with other viral pneumonias, the clinical findings are nonspecific and consist of fever, cough, dyspnea, and minimal sputum production. Increasing sputum production requires exclusion of a superimposed bacterial pneumonia. Timing is important for evaluating a pneumonia associated with measles. The development of primary viral pneumonia in rubeola is synchronous with the first appearance of a rash, whereas secondary bacterial pneumonias are most likely to occur from 1 to 7 days after the onset of the rash. Bacterial infection is strongly suggested in the patient with a typical measles rash whose condition improves over a period of days before pneumonia develops. A third type of pneumonia associated with measles pneumonia is histologically referred to as giant cell pneumonia. This may follow overt measles in otherwise normal, healthy children, but children with altered immunology may develop subacute or chronic, but often fatal, pneumonias. Pathologically, giant cell pneumonia is characterized by an interstitial mononuclear infiltrate with giant cells containing intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions.

Cytomegalic inclusion virus2 has few distinguishing clinical features, has a radiologic presentation suggestive of bronchopneumonia, and is frequently fatal in patients who are immunosuppressed. Histologically, the lung reveals a diffuse mononuclear interstitial pneumonia accompanied by considerable edema in the alveolar walls that may even spill into the alveolar spaces. In addition, the alveolar cells have characteristic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic occlusions. The radiologic opacities are the result of cellular infiltrates in the interstitium, as well as intra-alveolar hemorrhage and edema. Other viruses, including the Coxsackieviruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and respiratory syncytial viruses, may result in disseminated multifocal opacities. When the course of the viral infection is mild, confirmation is rarely obtained during the acute phase of the disease, but may be made by viral culture or acute and convalescent serologic studies.

Granulomatous Infections

Of the granulomatous infections most likely to produce ill-defined multifocal opacities of varying sizes, histoplasmosis127 is probably the best known (Fig 16-5 ). This form of histoplasmosis is usually seen after a massive exposure to Histoplasma capsulatum. Because the organism is a soil contaminant found primarily in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, the disease should be suspected when this pattern is seen in acutely ill patients from these endemic areas. A history of prolonged exposure to contaminated soil is frequently obtained and helps confirm the diagnosis. A marked rise in serologic titers is also confirmatory. The radiologic course is characterized by gradual healing of the process, involving contraction of the opacities; resolution of a large number of opacities; and the development of a pattern of scattered, more circumscribed nodules. This may precede the characteristic “snowstorm” appearance of multiple calcifications that develops as a late stage of histoplasmosis.

Figure 16-5.

Histoplasmosis is caused by a fungus and is well known to produce a radiologic appearance similar to that of lobular pneumonia.

Blastomycosis187,580187580 and coccidioidomycosis483 are the two other fungal infections likely to result in this pattern. These fungi are also soil contaminants with a well-defined geographic distribution. Coccidioidomycosis is primarily confined to the desert southwest of the United States, although the fungus may be found as a contaminant of materials such as cotton or wool transported from this area. The geographic distribution of blastomycosis is less distinct than that of either histoplasmosis or coccidioidomycosis, but it is generally confined to the eastern United States, with numerous cases reported from Tennessee and North Carolina.

Opportunistic fungal diseases,128 such as candidiasis,223 cryptococcosis, aspergillosis,222,744222744 and mucormycosis, may produce this pattern but are rarely encountered in patients who are immunologically normal (Figs 16-6, A and B ). Aspergillosis668 and mucormycosis41 are part of a small group of pulmonary infections that tend to invade the pulmonary arteries. These invasive fungal infections produce multifocal areas of consolidation as a result of pulmonary hemorrhage and infarction. Invasive aspergillosis is a well known cause of masses with ill-defined borders that may have the appearance of a halo on HRCT. Because of the infarction, these opacities also frequently cavitate and are often filled with a mass of necrotic tissue that causes the appearance of an air crescent sign on both plain film and computed tomography (CT).668,744668744

Figure 16-6.

A, Invasive aspergillosis with the pattern of lobular pneumonia is rare in the patient who is immunocompetent but occurs as a frequent manifestation of aspergillosis in patients who are immunologically suppressed. B, Lobular consolidations seen in A were preceded by a fine nodular pattern.

(From Blum J, Reed JC, Pizzo SV, et al. Miliary aspergillosis associated with alcoholism. Am J Roentgenol. 1978;131:707-709. Used with permission.)

Tuberculosis504 less commonly produces multifocal ill-defined opacities, but should be strongly considered in the case of an apical cavity followed by the development of this pattern. In such an instance, the opacities most probably are the result of bronchogenic dissemination of the organisms.

Large, poorly defined, masslike opacites may form by coalescence of small nodules.323 Usually the diagnosis is confirmed by sputum stains for acid-fast bacilli or by cultures.

Nocardia35,190,280,64035190280640 is another opportunistic organism that may produce multiple ill-defined opacities. It is probably better known for producing discrete nodules that cavitate, but these nodules are frequently preceded by the less well-defined opacities. As with aspergillosis and mucormycosis, nocardiosis is rarely encountered in the patient who is immunologically normal, but should be strongly suspected in immunocompromised patients. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by either transbronchial or open biopsy.

Sarcoidosis

Many authors have emphasized that patients with histologically documented sarcoidosis314,589,592314589592 may have a radiologic pattern of bilateral nodular or even masslike foci (Figs 16-7, A and B ). These opacites are often ill-defined borders, sometimes becoming confluent and showing air bronchograms (see Fig 16-2). The clinical manifestation of sarcoidosis is in striking contrast to that of the other inflammatory conditions. Patients with sarcoidosis are afebrile and often virtually asymptomatic, although they may complain of mild dyspnea. This marked disparity of the radiologic and clinical findings virtually eliminates all of the entities considered so far in this chapter. When the pattern of multifocal ill-defined opacities is combined with bilaterally symmetric hilar adenopathy and the typical clinical presentation of the disease, the diagnosis becomes nearly certain. In this diffuse pulmonary disease, confirmation of the diagnosis is easily obtained by transbronchial biopsy. The pathologic explanations for this presentation of sarcoidosis have stimulated considerable discussion in the radiologic literature. Some authors describe this pattern as nodular sarcoidosis, whereas others consider it an alveolar sarcoidosis. The radiologic features supporting the appearance of alveolar sarcoidosis are primarily those of confluent opacities with ill-defined borders that may contain air bronchograms. It should be pointed out that sarcoidosis rarely causes bilaterally symmetric confluent opacities with a bilateral perihilar (butterfly) distribution, as seen in acute alveolar edema, pulmonary hemorrhage, or alveolar proteinosis. Consequently, sarcoidosis is not a serious consideration in the differential of the pattern considered in Chapter 15. Heitzman314 reported histologic evidence that patients with this “alveolar pattern” may have massive accumulations of interstitial granulomas, which by compression of air spaces could mimic an alveolar filling process. This is essentially a form of compressive atelectasis. The histologic observation of a massive accumulation of interstitial granulomas can be easily confirmed by examination of a number of cases with this radiologic pattern. Therefore, this mechanism almost certainly accounts for some cases with this pattern.

Figure 16-7.

A, Multifocal opacites often resemble nodules and masses. B, The presence of air bronchograms and less well-defined borders on CT make metastatic nodules a less likely diagnosis. This is multinodular manifestation of sarcoidosis.

One feature of the alveolar form of sarcoidosis that is not readily explained by the foregoing observation is the very labile character of the infiltrations. Frequently, the opacities accumulate and disappear dramatically, either spontaneously or in response to steroid treatment. It seems unlikely that a massive accumulation of well-organized granulomas could resolve in a matter of days or even a few weeks. Another explanation for this radiologic pattern of fluffy opacities with ill-defined borders and air bronchograms is based on the frequent presence of peribronchial granulomas that cause bronchial obstructions. Peribronchial granulomas are frequently observed on bronchoscopy and HRCT.441 Distal to these bronchial obstructions there is, in fact, alveolar filling, not by sarcoid granulomas but by macrophages and proteinaceous material. Histologically, this pattern is basically an obstructive pneumonia. The clinical variability of alveolar sarcoidosis is probably accounted for by these two major histologic explanations. For instance, the confluent, heavy accumulation of sarcoid granulomas with resultant compressive atelectasis would not be expected to resolve in a short time, whereas the smaller accumulations of granulomas in the peribronchial spaces with distal obstruction could account for cases that follow a much more labile course and respond dramatically to steroid therapy. It should be emphasized that obstructive pneumonia in sarcoidosis is secondary to the obstruction of small, distal bronchi and bronchioles. It is very rare for sarcoid granulomas to obstruct large bronchi and produce lobar atelectasis.

Langerhans’ Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma) is another inflammatory condition of undetermined cause that may produce a pattern of multifocal ill-defined nodular opacities.1 The nodular phase of the disease is generally believed to represent the earlier radiologic findings, which may precede the development of a reticular pattern and even end with a honeycomb lung. There is typically an upper-lobe predominance in both the nodular and reticular phases of the disease. HRCT may confirm this upper-lobe distribution and is very sensitive for the detection of small, peripheral cystic spaces55,416,51155416511 (Figs 16-8, A-D ). Like sarcoidosis, eosinophilic granuloma is an afebrile illness with much milder symptoms than all of the infectious diseases hitherto considered. Although the cause is unknown, there is a strong association with cigarette smoking.1 Pathologically, the lesions consist of a granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and Langerhans’ cells. The earlier nodular lesions are more histologically characteristic than the late honeycomb changes, which basically consist of fibrous replacement of the earlier inflammatory infiltrates. This late appearance may be very similar to that of sarcoidosis. The radiologic identification of associated hilar or paratracheal adenopathy favors the diagnosis of sarcoidosis over Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. The diagnosis should be confirmed by biopsy.

Figure 16-8.

A, Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis is a cause of multifocal, poorly defined opacities with a tendency toward an upper-lobe predominance, as illustrated by this case. B, HRCT section through the upper chest reveals multiple, poorly defined nodular opacities with interspersed, coarse reticular opacities. C, Another section shows numerous medial subpleural cystic spaces that are commonly seen in combination with the multifocal opacities. D, A more basilar CT section shows a smaller number of opacities confirming the upper-lobe predominance that is characteristic of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis.

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), also known as bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP),115,132,523115132523 is assumed to be a subacute or chronic inflammatory process involving the small airways and alveoli. The radiologic presentation resembles that of bronchopneumonia with multifocal, patchy air-space consolidations (Figs 16-9, A and B ). Patients with the disease are often treated with antibiotics on the basis of a presumed diagnosis of pneumonia, but the process fails to clear. Corticosteroid therapy has been reported to produce clearing of the radiologic abnormalities. However, there is a high relapse rate following steroid withdrawal. The histologic description of bronchiolitis obliterans is similar to that expected with Swyer-James syndrome, but bronchiolitis obliterans is not a significant part of the histologic appearance of COP and the term BOOP is no longer a preferred description. COP has extensive alveolar exudate and fibrosis that may resemble or overlap the changes of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). According to Müller et al.,521 COP can be distinguished from UIP. COP has multifocal air-space opacities with normal lung volume, whereas UIP has irregular linear and nodular opacities with reduced lung volume.523

Figure 16-9.

A, COP produces multifocal ill-defined opacities that resemble bronchopneumonia. B, CT reveals multifocal air-space consolidations with a halo of ground-glass opacity that are peripheral with a lower-lobe predominance.

Eosinophilic Pneumonias

Pneumonias associated with eosinophilia,113,234,452113234452 either peripheral eosinophilia or eosinophilic infiltrates of the lung, constitute a category of diseases that may be regarded as either inflammatory or collagen vascular. Radiologically, these infiltrates appear as patchy areas of air-space consolidation that tend to be in the periphery of the lung115 (Fig 16-10 ). When these infiltrates become extensive, the radiologic picture has been compared with a photonegative picture of pulmonary edema because of the striking peripheral distribution of the opacities. These opacities have very ill-defined borders, tend to be coalescent, and frequently have air bronchogram effects.

Figure 16-10.

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia typically produces multifocal ill-defined opacities that tend to be in the periphery of the lung. This is often described as the photonegative of pulmonary edema. Note peripheral opacities with a clear area between opacities and the central pulmonary arteries.

There are two important groups of eosinophilic pneumonias. The first group consists of the idiopathic varieties of eosinophilic pneumonia that are generally divided into those associated with peripheral eosinophilia (referred to as Löffler's syndrome) and those that comprise primarily eosinophilic infiltrates in the lungs without peripheral eosinophilia (referred to as chronic eosinophilic pneumonia). Besides tending to be peripheral, the infiltrates have the additional characteristic of being recurrent and are frequently described as fleeting. The second group of pulmonary infiltrates associated with eosinophilia includes those with a known causal agent.458 A variety of parasitic conditions are associated with pulmonary infiltration and are likewise well known for the association of eosinophilia. These include ascariasis, Strongyloides infection, hookworm disease (ancylostomiasis), Dirofilaria immitis, and Toxocara canis infections (visceral larva migrans), schistosomiasis, paragonimiasis, and, occasionally, amebiasis.

Correlation of the clinical, laboratory, and radiologic findings often makes a precise diagnosis of parasitic disease a straightforward matter. For example, T. canis infection results from infestation by the larva of the dog or cat roundworm and has a worldwide distribution. The disease is most commonly encountered in children. The symptoms are nonspecific, but there is usually the physical finding of hepatosplenomegaly. There is also marked leukocytosis. In addition, liver biopsy usually reveals eosinophilic granulomas containing the larvae. The diagnosis of ascariasis is similarly made by laboratory identification of the organism. Larvae may be detected in either sputum or gastric aspirates, whereas the adult forms of ova may be found in stool. The disease is usually associated with a marked leukocytosis and eosinophilia. As mentioned earlier, the roentgenographic appearance is that of nonspecific, multifocal areas of homogeneous consolidation that are frequently transient and therefore virtually identical to the opacities described as Löffler's syndrome. Strongyloidiasis, like ascariasis, produces mild clinical symptoms at the same time that the roentgenogram demonstrates peripheral ill-defined areas of homogeneous consolidation. The diagnosis is made by finding larva in the sputum or in the stool. Exceptions to this clinical course occur in the compromised host. A fatal form of strongyloidiasis has been reported in patients who are immunologically compromised, particularly by corticosteroid drugs.

Amebiasis458 is rather different from the parasitic diseases described previously in both its clinical and radiologic presentations. Patients with amebiasis frequently have symptoms of amebic dysentery and complain of right-sided abdominal pain, which is related to the high incidence of liver involvement. There is often elevation of the right hemidiaphragm because of liver involvement and, as in other cases of subphrenic abscess, there is frequently right-sided pleural effusion. Furthermore, the areas of homogeneous consolidation are not evenly distributed throughout the periphery of the lung, as in other cases of eosinophilic infiltration, but tend to be in the bases of the lungs, particularly in the right lower lobe and right middle lobe. Because the roentgenologic opacities correspond to areas of abscess formation, these opacities occasionally cavitate.

Vascular Diseases

Septic emboli290 occur when a bolus of infectious organisms are released into the blood and spread to the peripheral pulmonary vessels. The first radiologic signs of septic emboli are small ill-defined peripheral opacities. As the infection spreads, the size of the opacities increases, leading to multifocal peripheral opacities. Septic embolization also has a high probability of cavitation, which makes it different from many of the other causes of this pattern. Clinical correlation is essential in the diagnosis of septic embolization. There should be a history of a significant febrile illness. Some infectious processes are especially known to be associated with septic embolism. These include sepsis, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, carbuncles, and right-sided endocarditis. Patients with right-sided endocarditis frequently have a history of intravenous drug abuse.

Wegener's granulomatosis and its variants are probably the best-known sources of pulmonary vasculitis.191,427,451,453191427451453 Clinical correlation is extremely important, because the classic form of Wegener's is associated with severe paranasal sinus and kidney involvement. A history of multifocal ill-defined opacities on the chest plain film, hemoptysis, and hematuria strongly suggests Wegener's granulomatosis or a variant. These entities frequently require careful histologic evaluation to differentiate them from other lesions that have been referred to as the pulmonary renal syndromes, including Goodpasture's syndrome and idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. Many opacities appearing on the plain film in Wegener's granulomatosis are areas of edema, hemorrhage, or even lung tissue necrosis. Ischemic necrosis results in cavitary opacities in approximately 25% of patients with Wegener's granulomatosis.212 These opacities are therefore more likely to be the result of the vasculitis with ischemia than to be true granulomas. Perivascular granulomas, in fact, may be very small and may contribute minimally to the radiologic opacities. Because of their similar radiologic presentations, there is a tendency for radiologists to combine the variants of Wegener's granulomatosis (limited Wegener's, bronchocentric granulomatosis, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis). Although this is generally appropriate, the entity of lymphomatoid granulomatosis may have a different prognosis, as suggested by Liebow.451,453451453 A group of patients who were initially diagnosed as having lymphomatoid granulomatosis and subsequently developed lymphoma. It should be emphasized that associated hilar adenopathy is atypical and unusual in patients with Wegener's granulomatosis. Minimal adenopathy has been shown in a small number of cases and probably represents reactive hyperplasia.3 The presence of lymphadenopathy should probably be regarded as a warning to question the diagnosis and to suspect the possible development of lymphoma in patients with lymphomatoid granulomatosis.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a lesser known cause of pulmonary vasculitis that may lead to the appearance of multiple areas of air-space consolidation and even an appearance similar to that of pulmonary edema.437,475437475 This rickettsial infection also results in a diffuse vasculitis. It is best diagnosed by the clinical findings of a rash and central nervous system findings. A history of tick bite and an increase in antibody titers strongly support the diagnosis.

Neoplasms

Neoplasms are not generally regarded as a common cause of multifocal ill-defined opacities in the lung. However, there are a few neoplasms that do produce this pattern and are somewhat characteristic in their radiologic appearance when compared with other pulmonary tumors.

Bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma326,589,740326589740 (Fig 16-11 ) is the primary lung tumor most likely to produce the radiographic appearance of multifocal ill-defined opacities, which often have air bronchograms.804 The biologic behavior of this tumor is significantly different from that of most other primary lung tumors because it tends to spread along the alveolar walls while leaving them intact. At the same time, the tumor spreads along the walls, there is a tendency for it to produce significant amounts of mucus, which may contribute to the ill-defined opacities. The preservation of the underlying lung architecture permits the tumor to spread around open bronchi and gives rise to air bronchograms. This radiologic pattern of multifocal ill-defined opacities resembles bronchopneumonia and requires careful clinical correlation. The CT patterns of bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma are usually a mixture of ground-glass opacities and air-space consolidations with air bronchograms.

Figure 16-11.

Bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma fills the air spaces with mucus and tumor cells. Bronchogenic dissemination accounts for the appearance of multifocal air-space opacities that may progress to cause diffuse consolidation.

Lymphoma23,432,589,592,61423432589592614 is another tumor that may involve multiple areas of the lung and produce the radiologic appearance of ill-defined opacities sometimes accompanied by air bronchograms (Figs 16-12, A and B ). When lymphoma involves the lung parenchyma, either primarily or secondarily, it spreads via the perivascular and peribronchial tissues and even by way of the interlobular septa. Histologically, its spread is considered to be an interstitial process. However, it is also well known that lymphomatous involvement of the lung may present with consolidative opacities that have ill-defined borders, and air bronchograms.443 This type of lymphoma has occasionally been described as alveolar lymphoma. There are at least three feasible explanations for this radiographic appearance of lymphoma: (1) the massive accumulation of tumor cells may destroy the alveolar walls and break into the alveolar spaces, (2) there may essentially be a compressive atelectasis or collapse of the alveolar spaces by the massive accumulation of lymphoma cells in the interstitium, and (3) because of the peribronchial infiltration, there may be an obstructive pneumonitis with secondary filling of the distal air spaces by fluid and inflammatory cells rather than lymphoma cells. Other lymphoid disorders of the lung194 including pseudolymphoma, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia,533,589533589 and angioblastic lymphadenopathy386 may result in a similar pattern.

Figure 16-12.

A, Pulmonary lymphoma is a cause of poorly marginated masses that may resemble consolidations. This case shows a large opacity in the left lower lobe, a peripheral subpleural opacity, and an opacity above the left hilum. There is also a subtle, diffuse fine reticular pattern. B, CT section of the same case of lymphoma shows multiple ill-defined opacities. There is an air bronchogram through the most anterior opacity, which has the appearance of a consolidation. There is also diffuse thickening of the interlobular septae. These findings are all the result of lymphomatous masses and infiltration.

The occurrence of metastases as multifocal opacities with ill-defined borders is uncommon and likely results from the superimposition of a large number of masses and nodules or invasive growth of masses into the surrounding lung. Poorly marginated metastases may also result from surrounding opacities including atelectasis or bleeding that obscures the margin of the masses. It has been suggested that choriocarcinoma may result in bleeding around the periphery of the tumor, giving the radiologic appearance of ill-defined opacities. However, Libshitz et al.447 presented more than 100 cases showing that this occurrence is exceptional.

Environmental Diseases

The environmental diseases most frequently associated with the pattern of multifocal ill-defined opacities include acute allergic alveolitis or hypersensitivity pneumonitis, silicosis, and coal worker's pneumoconiosis.393,555,715,720393555715720

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an allergic reaction at the alveolar capillary wall level to mold and other organic irritants. Initially it is an acute reaction consisting of edema with an inflammatory infiltrate in the interstitium. This inflammatory infiltrate may gradually be replaced by a granulomatous reaction with some histologic similarities to sarcoid granulomas. The multiple confluent opacities with air bronchograms tend to represent the acute phase of the disease, and a nodular or even a reticular pattern may be seen in the later stages. Confirmation of the diagnosis is best obtained by establishing a history of exposure followed by skin testing, serologic studies, and correlation with HRCT. Exposure histories are varied and include molds and fungi from sources such as moldly hay in farmer's lung, bird fancier's disease, bagassosis from mold in sugar cane, mushroom worker's lung, and hot tube lung. Hot tube lung may differ from the other causes of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in that it is a reaction to Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)304 rather than to molds.

Silicosis is another inhalational disease that frequently results in multiple opacities. The border characteristics of these opacities are quite different from those considered in the remainder of this discussion. These borders tend to be more irregular rather than truly ill-defined. The irregularities are the result of strands of fibrotic reaction around the conglomerate masses. In addition, the opacities tend to be much more homogeneous because they represent large masses of fibrotic reaction. There should be no normal, intervening alveoli to give a soft, heterogeneous appearance. Furthermore, there should be no evidence of air bronchograms. (Answer to question 3 is a.) These opacities tend to be in the periphery of the lung; however, they are frequently not pleural-based, rather, they appear to parallel the chest wall. The opacites are usually bilateral but may be asymmetric. As they enlarge, they are often masslike and described as progressive massive fibrosis (Fig 16-13 ). A history of exposure in mining or sandblasting is usually confirmatory. Coal worker's pneumoconiosis is radiologically indistinguishable from silicosis. Comparison with old films is essential to ensure stability and eliminate the possibility of a new, superimposed processes, such as tuberculosis or neoplasm.

Figure 16-13.

Predominantly upper-lobe opacities in this case of silicosis are similar to those in other cases in this chapter. Associated coarse reticular opacities are the result of interstitial scars. Progressive fibrosis causes the larger opacities to have irregular rather than ill-defined borders. This is often described as progressive massive fibrosis.

Aids-Related Diseases

Although PCP is the most common pulmonary infection in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), it tends to produce a pattern of more uniform reticular or confluent opacities. The appearance of scattered or patchy opacities requires consideration of a greater variety of infections and neoplasms including bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial pneumonias; lymphoma; and Kaposi's sarcoma.683

Bacterial pneumonias produce the same patterns in patients with HIV infection and in the general population.139 They occur during the early stages of HIV, while immune impairment is mild, with CD4 cell counts between 200 and 500 cells/µl.478 Streptococcus pneumoniae and H. influenzae are the most common organisms, but more virulent organisms such as Staphylococcus should be suspected when the pneumonias are complicated by cavitation.

Tuberculosis in patients who have early HIV infection (CD4 counts between 200 and 500 cells/µl) produces the same patterns seen in patients with normal immunity.299,676299676 Postprimary tuberculosis most often causes apical disease with cavitation. Bronchogenic dissemination of organisms from an apical cavity may lead to multifocal opacities that resemble bacterial bronchopneumonia. Following development of AIDS after the CD4 count is fewer than 200 cells/µl, patients are at increased risk for miliary tuberculosis653 with a fine nodular pattern, as seen in Chapter 17. Additionally, in patients with more severe immune impairment, tuberculosis is likely to cause combinations of segmental, lobar, or multifocal air-space opacities with hilar or mediastinal adenopathy resembling primary infection.271 Fungal infections are less frequent, but candida, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis have all been reported to produce patterns similar to tuberculosis in patients with AIDS.123,128,702123128702

MAC infection most frequently causes a diffuse, bilateral, reticulonodular pattern in patients with AIDS.474 In contrast, the patients with normal immunity who are at greatest risk for Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI) infection are patients with chronic pulmonary disease. In this latter group of patients, MAI may be radiographically indistinguishable from tuberculosis. The reticular pattern of MAI should be more coarse and disorganized than PCP; however, when PCP becomes chronic, it may cause a similar appearance. When MAI causes air-space opacities, it differs from PCP. The air-space opacities of MAI are either segmental or multifocal, and the multifocal opacities are more likely to resemble poorly marginated masses. PCP causes more uniformly diffuse air-space disease. Cases with air-space opacities are also often associated with pleural effusions or adenopathy, which may also be seen in tuberculosis but which are not expected in PCP. Disseminated MAI is a terminal infection that occurs after the CD4 count has declined below 50 cells/µl.

Lymphoma may produce multiple poorly marginated masses or multiple nodules. Lymphoma in patients with HIV is usually β-cell non-Hodgkin's124 and differs from patients with normal immunity in that AIDS-related lymphomas are more often extranodal.432,684432684 Lymphoma is probably the most likely diagnosis of lobulated pulmonary masses in patients with AIDS. These masses often show a very aggressive growth pattern and may double in size within 4 to 6 weeks.

Kaposi's sarcoma (Fig 16-14 ) is the most common AIDS-related neoplasm,124 but it has decreased in frequency for unexplained reasons. It is a highly vascular tumor that involves any mucocutaneous surface and produces characteristic red plaques. It is most commonly a skin lesion, but it also involves the trachea, bronchi, and lungs. The radiographic appearance of pulmonary opacities may result from atelectasis, hemorrhage, or hemorrhagic masses. Multiple nodules or masses are the most common pattern. More confluent, patchy air-space opacities may resemble PCP. Associated adenopathy or pleural effusions are reported to occur in 90% of patients with Kaposi's sarcoma and may help distinguish Kaposi's sarcoma from PCP, but their occurrence would not permit exclusion of mycobacterial infections. Sequential thallium and gallium scanning has been advocated as a technique for distinguishing PCP, Kaposi's sarcoma, and lymphoma. PCP is thallium negative but gallium positive on 3-hour delayed images. Lymphomas are thallium and gallium positive, and Kaposi's sarcoma is thallium positive but gallium negative.436 Bronchoscopy may establish the diagnosis of Kaposi's sarcoma. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy has also been advocated for diagnosis of focal and multifocal lesions.283,668283668 Lymphoma is an aggressive and often fatal neoplasm in contrast to Kaposi's sarcoma, which is an indolent, slow-growing tumor that is rarely fatal.

Figure 16-14.

Kaposi's sarcoma produces bronchial and pulmonary vascular tumors that are prone to hemorrhage. When these tumors bleed, they may appear more like air-space consolidations than masses.

Top 5 Diagnoses: Multifocal Ill-Defined Opacities

-

1

Bronchopneumonia

-

2

Sarcoidosis

-

3

Bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma

-

4

Granulomatous pneumonias

-

5

Septic emboli

Summary

Small multifocal ill-defined opacities are distinguished from miliary nodules by evaluation of their borders. Miliary nodules should be sharply defined.

Multifocal ill-defined opacities most commonly result from processes that involve both the interstitium and the air-spaces. Careful evaluation of the roentgenogram frequently reveals the classic signs for both components of the disease.

Bronchopneumonias typically present with this pattern.

Histoplasmosis is one of the most common fungi to produce the pattern.

Unusual pulmonary infections, including aspergillosis, mucormycosis cryptococcosis, and nocardiosis, may lead to the pattern in the patient who is immunologically compromised.

Sarcoidosis may lead to this pattern when there are extensive accumulations of granulomas or when small granulomas occlude bronchioles with a resultant obstructive pneumonia.

Eosinophilic pneumonias should be suspected when the opacities are peripherally located and recurrent or fleeting.

Multifocal opacities that develop after pulmonary embolism are usually explained by hemorrhage and edema. True infarction is most accurately diagnosed when serial films demonstrate development of either linear or nodular scars.

The large opacities seen in Wegener's granulomatosis frequently represent areas of necrosis or of hemorrhage and edema resulting from ischemia. Remember, Wegener's granulomatosis is a disease of the vessels.

Bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma is the only primary lung tumor that is expected to produce the pattern. Lymphoma and other lymphoid lesions of the lung (pseudolymphoma) may also lead to this pattern.

Kaposi's sarcoma in patients with AIDS is an increasingly important cause of this pattern. These patients usually have advanced cutaneous Kaposi's sarcoma. The pulmonary involvement must be distinguished from lymphoma and opportunistic infection. For unexplained reasons, the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma is declining.

Metastases rarely lead to this pattern. Choriocarcinoma has been reported to lead to ill-defined opacities, but this appears to be very rare.

Silicosis may lead to large, bilateral, irregular upper-lobe masses (conglomerate masses). They are fibrotic and should therefore not produce air bronchograms. Peripherally, their margins often parallel the lateral pleura.

Drug reactions frequently lead to this pattern. They are best diagnosed by clinical correlation. Biopsy is frequently required in the patient who is immunologically compromised to rule out opportunistic infection.

Answer Guide

Legends for introductory figures

Figure 16-1 Multifocal ill-defined opacities are a common pattern for bronchogenic spread of infection. This is an example of Klebsiella bronchopneumonia. The opacities represent lobular consolidations. The intervening lucencies are normal, aerated lobules.

Figure 16-2 The multifocal ill-defined opacities in this case are very nonspecific, but the observation of enlargement of the nodes in the aortic pulmonary window (left arrows) and paratracheal lymph nodes (right arrows) combines two patterns and thus narrows the differential. Either sarcoidosis or lymphoma could account for this combination. The fact that the patient is relatively asymptomatic supports the correct diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Answers

1. e 2. b 3. a