Abstract

In the oil and gas industry, pyrite forms one of the most hardened scales in reservoirs, which hinders the flow of fluids. Consequently, this leads to blockage of the downhole tubular, formation damage, and complete shutdown of production and operational processes. Herein, a new green formulation based on borax (K2B4O7) is proposed for pyrite scale removal. The temperature effect, disk rotational speed, and borax concentration have been investigated using a rotating disk apparatus. Also, XPS and SEM–EDX analyses were conducted on the pyrite disk surface before and after the treatment with the green formulation. The new formulation showed the potential ability to dissolve pyrite without generating the toxic hydrogen sulfide (H2S). The dissolution rate of the scale in the new formulation is increased by 16% compared to that in a previous green formulation composed of 20 wt %DTPA+9 wt % K2CO3. Molecular modeling technique using DFT was used to study the solvation energies of Fe2+ and Fe3+. The latter had a higher solvation energy than the former, which confirmed that upon using the borax-based formulation to oxidize Fe2+ to Fe3+. It will aid the dissolution of pyrite scales. The new formulation achieved a corrosion rate that is 25 times lower than that of 15 wt % HCl, which is commercially used in treating scales. Finally, the proposed new formulation does not require the use of corrosion inhibitors; hence, it is expected to result in a more economical scale treatment method.

1. Introduction

A persistent challenge faced by the upstream sector of the oil and gas industry is iron sulfide scales. This is especially true in sour gas wells, which operate at high pressure and high temperature.1,2 Iron sulfide scales hinder the assurance of flow by being deposited in the near-wellbore area of the reservoir. This brings about formation damage, blockage of the downhole tubular, and ultimately leads to disrupting the production and operational processes. There are different forms of iron sulfide scales, some of which include pyrrhotite (Fe7S8), troilite (FeS), greigite (Fe3S4), and pyrite (FeS2). The latter is one of the most challenging due to the high sulfur to iron ratio (2:1);3 a higher sulfur to iron ratio, corresponds to greater acidification.4 Iron sulfide scales are formed when hydrogen sulfide formed from the metabolic activities of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) reacts with ferrous iron produced from the corrosion of steel pipes in the production system.5 The presence of hydrogen sulfide has negative effects on both humans and industrial processes. Hence, the importance on preventing its formation and promoting its removal.6,7

Mechanical and chemical methods are the two popular methods for removing iron sulfide scales. The former includes the use of mechanical mills and jet blasters. However, these methods are costly, time-consuming, often enhance pitting corrosion, and more importantly, they cannot remove the scales deposited in the near-wellbore.1,8 As for the chemical methods, they are more popular as they are simple to use compared to the mechanical method and they can clean the scales deposited in the near-wellbore. Nevertheless, some chemicals such as hydrochloric acid lead to hydrogen sulfide generation, while others such as chelating agents are often slow in reaction and dissolution of the iron sulfide scales.9,10 In our preceding works,11−18 both experimental and computational methods have been implemented to investigate iron sulfide scale removal by using green materials such as chelating agents. However, there are still many challenges particularly concerning pyrite, which is quite difficult to remove. Hence, there is a need to develop a green formulation with effective performance for removing iron sulfide scales from oil and gas wells.

Besides chelating agents, oxidizers can convert pyrite into oxides of iron (FeO and Fe2O3), which are easier to remove than pyrite. This method of using the oxidizing agent has been used earlier in removing iron sulfide sludge in the water-flood injection system in which chlorine dioxide (ClO2) was used as the oxidizer.19 However, it was observed that this reaction involves the formation of elemental sulfur, which aggravates the situation by enhancing corrosion.

In this work, the effectiveness of potassium tetraborate tetrahydrate (borax) in oxidizing and dissolving pyrite scales is investigated under high pressure and high temperature (HPHT) conditions with the aid of a rotating disk apparatus (RDA). Borax is an environmentally friendly chemical. It has been used in liquid laundry and dishwashing product industry for several years, it has low acute toxicity and do not have any genotoxic or carcinogenic potential.20,21 It was reported20 to pose no hazard to human health under conditions of usual handling and usage. Pyrite oxidative dissolution is the primary cause of acid mine drainage (AMD) formation, which has a major effect on the quality of water in mining regions around the world. Numerous studies were conducted to clarify the chemistry of pyrite dissolution22−32 to boost the capability of identifying and forecasting AMD generation.

Borax has been applied in the oilfield industry as a cross-linker for gelled pigs in cleaning pipes.33 It has also been used in conjunction with xanthan gum in hydraulic fracturing.33,34 Moreover, it is used as a safe and more effective material in gold extraction compared to mercury;35 hence, borax is chosen for this study. The RDA has been used extensively in the oil and gas industry for studying reaction kinetics3,36 including pyrite.37 Different parameters, including temperature and composition, were varied to determine the optimal conditions for the application of the oxidizing agent in pyrite scale removal. Furthermore, theoretical calculations38,39 using density functional theory (DFT) were performed to support the experimental work and provide fundamental understanding on the correlation between the oxidation state of iron and its solvation.

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Fe2+/Fe3+ Solvation

Computational studies using DFT calculations were carried out to provide insights into the change in the oxidation state of iron in pyrite after undergoing oxidation from the new formulation using borax. Experimental results showed that the dissolution rate has improved after Fe2+ has been oxidized to Fe3+. Our earlier work,38 which used molecular dynamics had shown that the interaction between the potassium and sulfur atom was the predominant factor in pyrite dissolution. Herein, we use another computational technique, DFT, to understand pyrite dissolution by studying the solvation of Fe2+and Fe3+ ions.

Both Fe2+and Fe3+ form a perfect octahedral geometry after being optimized with six water ligand molecules (Figure 1) forming six bonds made up of four equatorial and two axial bonds. The binding affinity of each ion to the ligands was calculated using eq 1.

| 1 |

Figure 1.

Optimized structures (in solvent) for (A) Fe2+(H2O)6 and (B) Fe3+(H2O)6 and their corresponding electrostatic potential map of (C) Fe2+(H2O)6 and (D) Fe3+(H2O)6. ax = axial, eq = equatorial.

Fe2+ had a binding affinity of 56.747 while Fe3+ had a binding affinity of −4.532 kcal mol–1. Fe3+ had a much strong binding affinity to water molecules as a negative value denotes good binding while a positive value corresponds to poor binding affinity. This implies that upon oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, iron would easily bond to water molecules, which would improve solvation. Shorter bond lengths (Table 1) with oxygen atoms of the water ligand were observed in Fe3+(H2O)6 compared to Fe2+(H2O)6, which demonstrates the strong binding affinity observed in Fe3+. The shortest bond lengths observed in the axial bonds (2.016 Å) of Fe3+(H2O)6, while for Fe2+(H2O)6, it occurred in two of the equatorial bonds (2.129 Å) and the longest bond (2.152 Å) is observed in the alternating bonds, hence vitiating one another. On the other hand, there is no significant difference between the axial and equatorial bond lengths in Fe3+(H2O)6.

Table 1. Selected Bond Lengths of the Optimized Structures (in Solvent) for Fe2+ (H2O)6 and Fe3+ (H2O) 6.

| bond length (Å) | Fe2+ | Fe3+ |

|---|---|---|

| Fe–O2 | 2.129 | 2.017 |

| Fe–O5 | 2.152 | 2.018 |

| Fe–O8 | 2.129 | 2.017 |

| Fe–O11 | 2.153 | 2.018 |

| Fe–O14 | 2.146 | 2.016 |

| Fe–O17 | 2.146 | 2.016 |

The solvation energy (ΔGsolv) was calculated using eq 2(40)

| 2 |

A high negative value for the ΔGsolv of solution corresponds to an ion that is likely to solvate, while a high positive value means that solvation will not occur. Fe2+(H2O)6 and Fe3+(H2O)6 both had ΔGsolv values of −176.362 and −405.745 kcal/mol, respectively. The latter had a higher negative value, which further validated the earlier observations in both binding affinity and bond length that Fe3+ is more soluble than Fe2+. Hence, the computational investigation provided an insight that oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ would aid in pyrite dissolution, as the latter would be remain solvated than the former. The electrostatic potential (ESP) map (Figure 1) of both compounds further attest to this as the ESP of Fe3+(H2O)6 has a deeper blue color than Fe2+(H2O)6. The acidity of an ion is dependent on its ability to pull electrons toward itself. Fe3+ pulls the electrons more strongly toward itself than Fe2+.42 The electrons in the O–H bonds from water molecules are pulled away from the hydrogens and closer to the oxygen in Fe3+(H2O)6 than Fe2+(H2O)6. This implies that the hydrogen atoms in the ligand water molecules in Fe3+(H2O)6 have a greater positive charge and hence are more attracted to water molecules in the solution than Fe2+(H2O)6. This attraction makes them be readily donated to the surrounding water molecules to form a hydroxonium ion (H3O+) and hence they are more acidic than Fe2+(H2O)6.41−43 This further explained the reason why Fe3+ ions are more acidic than Fe2+.

2.2. Effect of Borax Concentration on Pyrite Dissolution

Three dissolution experiments using an RDA were performed to study the effect of potassium tetraborate (borax) concentration on pyrite dissolution. All experiments were carried out at 1000 psi, 150 °C for 30 min. Samples were taken regularly every 5 min. After that analyzed for iron concentration using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) and the results are shown in Figure 2. The iron dissolution rate increased with the increase in concentration up to 14 wt %. However, a decrease in the rate occurred at a concentration of 20 wt % (Figure 2). The optimum concentration of borax that yields maximum pyrite dissolution was determined as 14 wt %. Then, the optimum concentration of potassium tetraborate was then used in the subsequent experiments to study the influence of temperature, disk rotational speed, and corrosion rate. As seen in Figure 3, the obtained dissolution rate at the studied concentration is reported in (mol cm–2 s–1). The dissolution rate of pyrite using the new borax formulation outperformed its dissolution in formulation of DTPA/K2CO3 reported in ref (3) at the same conditions by 16.6%. The dissolution rates achieved by borax formulation and DTPA/K2CO3 is 7.77 × 10–9 and 6.48 × 10–9 (mol cm–2 s–1), respectively.

Figure 2.

Effect of Borax concentration on pyrite dissolution (P = 1000 psi; T = 150 °C; rpm = 1200).

Figure 3.

Effect of borax concentration on the dissolution rate of pyrite.

2.3. Effect of Temperature on Pyrite Dissolution

The effect of temperature on the iron dissolution rate in the new

formulation has been assessed. Two experiments were conducted at 100

and 150 °C to represent both shallow and deep hydrocarbon wells,

respectively. All experiments were performed at 1200 rpm, 1000 psi

for 30 min. About 3 mL of the sample was collected through an auto

sampler every 5 min then analyzed for iron concentration using ICP-OES.

From the plot of iron concentration versus time (Figure 4), the dissolution rate was

calculated (Figure 5). Iron concentration after 30 min has almost doubled when the temperature

was increased to 150 °C. The dissolution rate of pyrite increased

by four folds when the temperature was raised from 100 to 150 °C.

The activation energy for the dissolution was calculated from the

expression −rA = ke–E/RT. The ratio

of the two dissolution rates  is used to calculate activation energy as

3.41 × 104 J/mol.

is used to calculate activation energy as

3.41 × 104 J/mol.

Figure 4.

Concentration of iron versus time at different temperatures in borax.

Figure 5.

Effect of temperature on the dissolution rate of pyrite in borax solution.

2.4. Effect Disk Rotational Speed on Pyrite Dissolution

The effect of the speed of the rotating disk on the dissolution rate of pyrite was also investigated. The RDA experiments were conducted at two different speeds 600 and 1200 rpm. In studying the rpm effect, other conditions such as pressure, temperature, and time were held constant while the rpm was varied. All tests were conducted at 1000 psi, 150 °C for 30 min. Effluent samples of 3 mL were taken every 5 min then analyzed for iron concentration using ICP-OES. The results showed that the dissolution rate of pyrite in the new formulation is significantly affected by the rpm. Figure 6 shows that the dissolution rate of pyrite increased with an increase in the rotational disk speed, implying that the dissolution is mass transfer limited. The dissolution rate at 600 and 1200 rpm was determined to be 2.12E-09 and 7.77E-09 (mole/cm2/s), respectively.

Figure 6.

Effect of rpm on the dissolution rate of pyrite in borax solution.

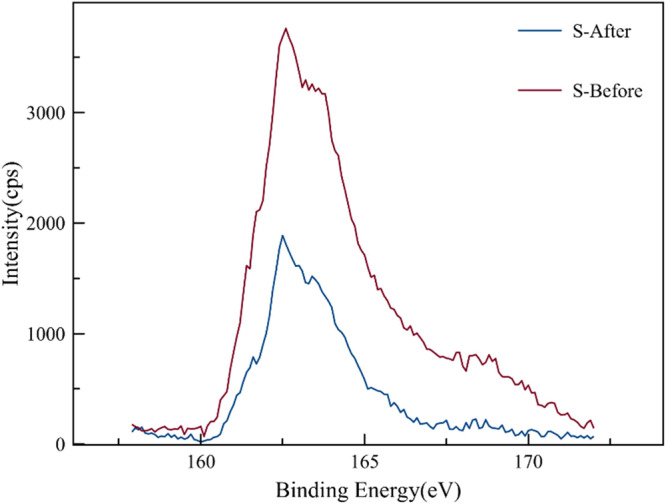

2.5. XPS Results

XPS is a renowned tool for characterizing solid surfaces to determine the binding energies of the elements on the surface of a material. The binding energies of the elemental sulfur in its various forms are expected to be found within a range of 160–178 eV.3Figure 7 depicts the XPS spectra both before (red line) and after (blue line) treatment with borax. Sulfide occurs within 160 to 163 eV and this peak was observed in both spectra. However, the intensity of the peak is reduced after treatment of the material with borax. This confirms the dissolution of pyrite in borax solution since the sulfide peak has reduced intensity. Furthermore, another peak was observed around 164 eV in the blue spectrum, which represents elemental sulfur and was not observed in the red spectrum (untreated sample). This further substantiates the hypothesis that pyrite (FeS2) has dissolves in the borax solution and oxidizes sulfide to elemental sulfur. The proposed reactions that yield elemental sulfur are shown below.

Figure 7.

XPS spectra for pyrite before (red line) and after (blue line) treatment with borax.

2.6. Corrosion Test Results

To evaluate the corrosivity of the new formulation, two corrosion experiments were conducted using the RDA. The first involved the new formulation of borax while the second experiment was done with 15 wt % HCl with a 1000 ppm corrosion inhibitor (CI). The commercial CI used is melamine, which is commonly used in the oil industry.44 The tests were conducted at high temperature that represents deep sour gas wells. Both corrosion tests were performed at 150 °C, 1000 psi for 6 h and under static conditions. The results obtained from the corrosion test showed that the new formulation has a corrosion rate of 0.021 mm/y while that of 15 wt % HCl with a CI has a rate of 0.511 mm/y, which is 25 times lower than the commercial formulation (Figure 8). Also, Figure 8 illustrates the coupons of mild steed (MS) before and after treatment with both the new formulation and 15 wt % HCl with the CI. Interestingly, the MS coupon was dissolved after the treatment with HCl formulation, despite the use of a corrosion inhibitor, while in the case of borax formulation MS remained undissolved. It worth mentioning that MS has higher corrosion tendency than high carbon steel (CS), which is usually used in the tubular system in the sour gas wells. Hence, the use of MS here is for comparison purposes only. Therefore, the actual corrosion rate for the new formulation for CS is expected to be lower than the observed values for MS.

Figure 8.

Corrosion rate results for both borax and HCl + 1000 ppm CI formulations.

2.7. Comparison Analysis

The new formulation of 14 wt % borax (14 wt % of borax powder and 84 wt % of DI water)

achieved pyrite dissolution that surpassed our previous formulation of a chelating agent and a converter.3,13,45 The reaction rate of the borax formulation has shown an improvement of 16% compared to the DTPA/K2CO3 formulation. The incremental dissolution of pyrite with the use of the borax formulation is depicted in Figure 9 and a comparison of its dissolution in different green formulations is shown in Figure 10. The results show that the new borax formulation is superior in performance in comparison with other available green formulations.

Figure 9.

Comparison of iron concentration versus time for borax and DTPA/K2CO3 formulations.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the dissolution rate of pyrite using different green formulations.

3. Conclusions

In this study, a new green formulation is developed for the removal of pyrite, FeS2, scales from oil and gas tubings. Both theoretical analysis using DFT computational analysis and experimental work based on dissolution kinetics are performed under typical reservoir conditions. Corrosion tests are conducted to evaluate the impact of the different formulations on the oil and gas tubular system. Also, XPS analysis was used to provide an insight into the chemistry of the reactions on the pyrite surface. Here are the main conclusions of this investigation:

A new green formulation for pyrite scale removal is presented in this study. It is composed of potassium tetraborate tetrahydrate with 14 wt % concentration.

The effect of temperature, rotating disk speed, and borax concentration on the dissolution rate of pyrite using the new borax formulation was studied using a rotating disk apparatus.

The rotating disk apparatus experiments have shown an increase of 16% in the pyrite dissolution rate using the borax formulation in comparison to the DTPA+K2CO3 formulation.3,12

The borax formulation is more cost effective than 20 wt % DTPA+ 9 wt % K2CO3 formulation since it contains no chelating agent.

In addition to the dissolution experiments, corrosion experiments were conducted on mild steel to compare the corrosion rate of the borax formulation with HCl formulation, which is used commercially for scale removal. The borax formulation achieved a corrosion rate that is 25 times lower than the commercial formulation.

DFT studies confirmed that upon oxidation of pyrite from +2 to +3 state, the binding affinity of iron to water molecules has significantly increased, thereby aiding dissolution.

The new green borax formulation has good solubility and a very low corrosion rate for its application in the oil and gas industry.

4. Materials and Methodology

4.1. Experimental Details

4.1.1. Materials

Advanced Technology &

Industrial Co., Ltd. Hong Kong, supplied the chemical potassium tetraborate

tetrahydrate (K2B4O7 4H2O-borax) with 99.5% purity. Pyrite rock samples were purchased from

Geology Superstore Company, Britain. Cores of 1 inch diameter were

drilled from the sample. Finally, a 0.5 inch thickness and 1 inch

diameter disks were prepared with one surface highly polished and

smoothed. Pyrite samples were manually polished using lubricant-loaded

napless polishing cloths and 15, 6, and 1 μm diamond paste.

This polished disk surface was the only surface that was subjected

to the chemical formulation while all other sample surfaces were isolated

using harsh environment Teflon tubes. These tubes shrink with temperature

and insulate surfaces as shown in Figure 11. The specific surface area of the disk

was calculated using the formula reported in46 , where the A0 is the initial surface area of the pyrite disk (cm2), AC is the cross-sectional area (cm2), and Ø is the disk porosity.

, where the A0 is the initial surface area of the pyrite disk (cm2), AC is the cross-sectional area (cm2), and Ø is the disk porosity.

Figure 11.

Pyrite disk with all surfaces covered with Teflon tubing except the surface subjected to the reaction.

4.1.2. Material Characterization

The purity of the pyrite rock samples was determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectroscopy. Also, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was used to explain the chemical changes on the pyrite surface both before and after being treated with borax.

4.1.3. Reaction Rate Measurement Using a Rotating Disk Apparatus (RDA)

The pyrite disk sample was soaked into 0.1 N HCl for 30 min then rinsed used deionized water to ensure the reproducibility of the results by dissolution of fine particles at the surface as recommended in the literature.47 The schematic of the RDA used in this study is illustrated in Figure 12. The main components of the equipment are a reactor, reservoir fluid tank, poster pump, vacuum pump, pressure vessel, automatic sampling system, network of connecting valves, computer with monitoring, and control system. The reaction between the solid surface and the chemical formulation takes place in the reactor.

Figure 12.

Rotating disk apparatus (a) equipment and (b) schematic flowchart. a-labels:1-Manual valve; 2-Pneumatic valve; 3-Vent; 4-Stirrer; 5-Pressure vessel; 6-Pump booster; 7-Vacuum pump; 8-Auto sampler; 9-Reactor; and 10-Reservoir(Formulation tank).

4.1.4. Steel Corrosion Test

Two corrosion tests were conducted using borax and HCl formulations. Borax (14 wt %) was used as it is the optimal concentration that yielded the maximum solubility of the pyrite sample. HCl was used in this work for comparison as a standard. The former is widely used in the oil and gas industry for the removal of iron sulfide scales. The corrosion experiments were performed using coupons from mild steel. It is worth mentioning that MS has higher corrosion tendency than high carbon steel (CS), which is usually used in the tubular system in the sour gas well. Hence, the use of MS here is for comparison purposes only. Therefore, the actual corrosion rate for the new formulation for CS is expected to be lower than the observed values for MS. The composition of mild steel coupons is depicted in Table 2.48 The tests were carried out using an RDA as illustrated in Figure 2. The experiments were performed at 150 °C and 1000 psi, which is the typical temperature and pressure in deep sour gas wells. In these experiments, 14 wt. % K2B4O7-4H2O and 15 wt. % HCl, containing 1000 ppm of a corrosion inhibitor (CI), were employed. Both corrosion experiments were carried out for 6 h.

Table 2. Elemental Composition of MS.

| element | wt % |

|---|---|

| C | 0.128 |

| Si | 0.25 |

| Mn | 0.7 |

| S | 0.03 |

| P | 0.04 |

| Cu | 0.15 |

| Fe | bal. |

The corrosion rate was calculated from the weight loss method using eq 3.49,50

| 3 |

whereCrate = corrosion rate (millimeter per year); W = weight loss (milligrams), D = density of metal (g /cm3), A = sample surface area in (cm2), and T = exposure time of the metal sample (h).

4.2. Computational Details

To get a better understanding of the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe 3+ and why the latter has a better dissolution, solvation studies of both ions were carried out with the aid of density functional theory (DFT). DFT is a renowned and useful tool,51−53 which helps to provide atomistic insight into understanding chemical processes and has been used earlier for studying pyrite scale removal by chelating agents.11,12,15,16 All calculations were done using Gaussian 0954 at the B3LYP (Becke-3 Lee, Yang and Parr) and def-2-TZVP (default-2 triple-zeta valence polarization) level of theory and basis set, respectively. The former is well known for optimizing geometries55 and predicting energetics of molecules at a reasonable time with respect to the computational cost,56 while the latter known as the Ahlrich’s basis set and ensures that only the valence orbitals are split and polarization functions are included to ensure accuracy.57 Both Fe2+ and Fe3+ were bonded to six water ligands in the octahedral geometry to form hexa-aqua-iron complexes. That is, each of the six water molecules are attached to the central metal ion through a coordinate bond. This coordinate bond is from one of the lone pairs on the oxygen in each water molecule. Hence, the name hexa (six) and aqua (water) iron complex. The calculations were carried out in both vacuum and solvent phases to enable the calculation of the solvation energies. The latter was done using the polarizable continuum model-self-consistent reaction field (PCM-SCRF) model.58 The quintet and sextet states were used for Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions as they are the most stable spin states for the two ions, respectively.59 All calculations had no imaginary frequencies for the vibrational analysis, which confirmed that a true global minimum had been reached and the thermodynamic results are reliable. The solvation and binding energies were calculated from the optimized structures of the calculations.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant # NPRP9-084-2-041 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The findings achieved herein are solely the responsibility of the authors. Qatar University and the Gas Processing Center are acknowledged for their support. Analysis of iron concentrations were done in the Central Laboratories Unit, Qatar University. The authors also would like to thank AkzoNobel for providing the chelating agent used in this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Chen T.; Wang Q.; Chang F.; Aljeaban N.. Recent Development and Remaining Challenges of Iron Sulfide Scale Mitigation in Sour Gas Wells. International Petroleum Technology Conference 2019, 10.2523/IPTC-19315-MS. [DOI]

- Okocha C.; Kaiser A.; Wylde J.; Petrozziello L.; Haeussler M.; Kayser C.; Chen T.; Qiwei W.; Chang F.; Klapper M.. Review of Iron Sulfide Scale: The Facts & Developments and Relation to Oil and Gas Production. SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition 2018, 10.2118/192207-MS. [DOI]

- Ahmed M.; Saad M. A.; Hussein I. A.; Onawole A. T.; Mahmoud M. Pyrite Scale Removal Using Green Formulations for Oil and Gas Applications: Reaction Kinetics. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 4499–4505. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b00444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bini C.; Maleci L.; Wahsha M.. Mine Waste: Assessment of Environmental Contamination and Restoration. In Assessment, Restoration and Reclamation of Mining Influenced Soils; Jaume B.; Claudio B.; Mariya A. Ed.; Academic Press, 2017; pp 89–134. [Google Scholar]

- Onawole A. T.; Hussein I. A.; Saad M. A.; Nimir H. I.; Ahmer M. E. M. Computational Screening of Potential Inhibitors of Desulfobacter Postgatei for Pyrite Scale Prevention in Oil and Gas Wells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2018, 3, 327957. 10.1101/327957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.; Fan C.; Sun J.; Shang C. Oxidation of Iron Sulfide and Surface-Bound Iron to Regenerate Granular Ferric Hydroxide for in-Situ Hydrogen Sulfide Control by Persulfate, Chlorine and Peroxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 336, 587–594. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.12.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Kim D. Enhanced Adsorptive Removal of Hydrogen Sulfide from Gas Stream with Zinc-Iron Hydroxide at Room Temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 363, 43–48. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.01.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree M.; Eslinger D.; Fletcher P.; Miller M.; Johnson A.; King G. Fighting Scale Removal and Prevention. Oilf. Rev. 1999, 11, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano G.; Granado A.; Rincon A.; Hussein I.. A Compositional Simulation Evaluation of the Santa Rosa, Colorado EF Reservoir, Eastern Venezuela .In Proceedings of SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition 1988, 10.2118/18279-MS. [DOI]

- Jones C.; Downward B.; Edmunds S.; Curtis T.; Smith F.. THPS: A Review of the First 25 Years, Lessons Learned, Value Created and Visions for the Future. Pap. 1505, Corros. 2012 NACE Conf. Expo 2012, 1–14.

- Onawole A. T.; Hussein I. A.; Sultan A.; Abdel-Azeim S.; Mahmoud M.; Saad M. A. Molecular and Electronic Structure Elucidation of Fe 2+ /Fe 3+ Complexed Chelators Used in Iron Sulphide Scale Removal in Oil and Gas Wells. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 97, 2021–2027. 10.1002/cjce.23463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M.; Onawole A.; Hussien I.; Saad M.; Mahmoud M.; Nimir H.. Effect of PH on Dissolution of Iron Sulfide Scales Using THPS. SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry 2019, 10.2118/193573-MS. [DOI]

- Mahmoud M.; Hussein I. A.; Sultan A.; Saad M. A.; Buijs W.; Vlugt T. J. H. Development of Efficient Formulation for the Removal of Iron Sulphide Scale in Sour Production Wells. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 96, 2526–2533. 10.1002/cjce.23241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal M. S.; Hussein I.; Mahmoud M.; Sultan A. S.; Saad M. A. S. Oilfield Scale Formation and Chemical Removal: A Review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 171, 127–139. 10.1016/j.petrol.2018.07.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs W.; Hussein I. A.; Mahmoud M.; Onawole A. T.; Saad M. A.; Berdiyorov G. R. Molecular Modeling Study toward Development of H2S-Free Removal of Iron Sulfide Scale from Oil and Gas Wells. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 10095–10104. 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b01928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onawole A. T.; Hussein I. A.; Saad M. A.; Mahmoud M.; Ahmed M. E. M.; Nimir H. I. Effect of PH on Acidic and Basic Chelating Agents Used in the Removal of Iron Sulfide Scales: A Computational Study. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 178, 649–654. 10.1016/j.petrol.2019.03.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud M. A. N.; Badr Salem B. G.; Hussein I. A.. Method for Removing Iron Sulfide Scale from Oil Well Equipment. U.S. Patent 10,323,173, June 18, 2019.

- Mahmoud M. A. N.; Badr Salem B. G.; Hussein I. A.. Method for Removing Iron Sulfide Scale. U.S. Patent 9,783,728 B2, October 10, 2019.

- Romaine J.; Strawser T. G.; Knippers M. L. Application of Chlorine Dioxide as an Oilfield Facilities Treatment Fluid. SPE Prod. Facil. 2007, 11, 18–21. 10.2118/29017-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Team H. S.Human and Environmental Risk Assessment on Ingredients of Household Cleaning Products Substance : Boric Acid (CAS No 10043-35-3) December 2005 (Environment) March 2005 (Human Health). 2005, No. 10043.

- Çelikezen F. Ç.; Turkez H.; Togar B.; Izgi M. S. DNA Damaging and Biochemical Effects of Potassium Tetraborate. J. Excli. 2014, 13, 446–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer P. C.; Werner S. Oxygenation of Ferrous Iron. Water Poll. Cont. Res. Ser. 1970, 14010. [Google Scholar]

- Iron F. Aqueous Oxidation of Pyrite by Molecular Oxygen. Chem. Rev. 1982, 82, 461–497. 10.1021/cr00051a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Polanco C.; Ghahreman A. Fe ( III )/ Fe ( II ) Reduction-Oxidation Mechanism and Kinetics Studies on Pyrite Surfaces. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 774, 66–75. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2016.04.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart B. W.; Capo Æ. R. C. Comparison of Dissolution under Oxic Acid Drainage Conditions for Eight Sedimentary and Hydrothermal Pyrite Samples Comparison of Dissolution under Oxic Acid Drainage Conditions for Eight Sedimentary and Hydrothermal Pyrite Samples. Environ. Geol. 2008, 56, 171–182. 10.1007/s00254-007-1149-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mckibben M.; Barnh H. L. Oxidation of Pyrite in Low Temperature Acidic Solutions : Rate Laws and Surface Textures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1986, 50, 1509–1520. 10.1016/0016-7037(86)90325-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moses C.; Herman J. S. L Pyrite Oxidation at Chumneutral PH. J. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 471–482. 10.1016/0016-7037(91)90005-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnissel-gissinger P.; Alnot M.; Poincare H. Surface Oxidation of Pyrite as a Function of PH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 2839–2845. 10.1021/es980213c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M. A.; Rimstidt J. D. The kinetics and electrochemical rate-determining step of aqueous pyrite oxidation. J. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1994, 58, 5443–5454. 10.1016/0016-7037(94)90241-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonen M.; Elsetinow A.; Strongin D.; Brook S.; Ny S. B. Effect of Temperature and Illumination on Pyrite Oxidation between PH 2 and 6. Geochem. Trans. 2000, 1, 1467–4866. 10.1186/1467-4866-1-23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paschka M. G.; Dzombak D. A. Use of Dissolved Sulfur Species to Measure Pyrite Dissolution in Water at PH 3 and 6. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2004, 21, 411–420. 10.1089/1092875041358502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson L. J.; Crundwell F. K. The Anodic Dissolution of Pyrite (FeS2) in Hydrochloric Acid Solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 143, 42–53. 10.1016/j.hydromet.2014.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purinton R. J., JrAqueous Crosslinked Gelled Pigs for Cleaning Pipelines,US Patent Number: 4,543,131 September 24 1985.

- Fischer C. C.; Navarrete R. C.; Constien V. G.; Coffey M. D.; Asadi M.. Novel Application of Synergistic Guar/Non-Acetylated Xanthan Gum Mixtures in Hydraulic Fracturing. International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry 2001, 10.2118/65037-MS. [DOI]

- Appel P. W. U.; Na-Oy L. The Borax Method of Gold Extraction for Small-Scale Miners. J. Heal. Pollut. 2015, 2, 5–10. 10.5696/2156-9614-2.3.5.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nigo R. Y.; Chew Y. M. J.; Houghton N. E.; Paterson W. R.; Wilson D. I. Experimental Studies of Freezing Fouling of Model Food Fat Solutions Using a Novel Spinning Disc Apparatus. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 6131–6145. 10.1021/ef900668f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galukhin A.; Gerasimov A.; Nikolaev I.; Nosov R.; Osin Y. Pyrolysis of Kerogen of Bazhenov Shale: Kinetics and Influence of Inherent Pyrite. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 6777–6781. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b00610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onawole A. T.; Hussein I. A.; Ahmed M. E. M.; Saad M. A.; Aparicio S. Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics of the Dissolution of Oilfield Pyrite Scale Using Borax. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 302, 1–10. 10.1021/jp960480+.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onawole A.; Hussein I.; Saad M.; Ahmed M.; Aparicio S.. Application of DFT in Iron Sulfide Scale Removal from Oil and Gas Wells. In Third EAGE WIPIC Workshop: Reservoir Management in Carbonates 2019 2019, 1–5, 10.3997/2214-4609.201903111. [DOI]

- Sutton C. C. R.; Franks G. V.; Da Silva G. First Principles PKa Calculations on Carboxylic Acids Using the SMD Solvation Model: Effect of Thermodynamic Cycle, Model Chemistry, and Explicit Solvent Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 11999–12006. 10.1021/jp305876r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J.Complex Metal Ions - the Acidity of the Hexaaqua Ions. 2003, pp 1–9.

- Jafri J. A.; Logan J.; Newton M. D. Ab Initio Study of Inner Solvent Shell Reorganization in the Fe 2+ -Fe 3+ Aqueous Electron Exchange Reaction. Isr. J. Chem. 1980, 19, 340–350. 10.1002/ijch.198000043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheers N.; Andlid T.; Alminger M.; Sandberg A.-S. Determination of Fe2+ and Fe3+ in Aqueous Solutions Containing Food Chelators by Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry. Electroanalysis 2010, 22, 1090–1096. 10.1002/elan.200900533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma C.; Haque J.; Ebenso E. E.; Quraishi M. A. Results in Physics Melamine Derivatives as Effective Corrosion Inhibitors for Mild Steel in Acidic Solution : Chemical , Electrochemical, Surface and DFT Studies. Results Phys. 2018, 9, 100–112. 10.1016/j.rinp.2018.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud M.; Ba Geri S.; Hussein I.. Method for Removing Iron Sulfide Scale from Oil Well Equipment. US Patent No. 10,323,173. Jun 18, 2019.

- Sayed M. A.; Nasrabadi H. Reaction of Emulsified Acids With Dolomite. Jcpt 2013, 52, 164–175. 10.2118/151815-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredd C. N.The Influence of Transport and Reaction of Wormhole Formation in Carbonate Porous Media: A Study of Alternative Stimulation Fluids. ProQuest Diss. Theses 1997, 209–209, 10.1006/jcis.1998.5535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Haddad M. A. M.; Bahgat Radwan A.; Sliem M. H.; Hassan W. M. I.; Abdullah A. M. Highly Efficient Eco-Friendly Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in 5 M HCl at Elevated Temperatures: Experimental & Molecular Dynamics Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–15. 10.1038/s41598-019-40149-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. A.Principles and Prevention of Corrosion. 2nd Ed; Prentice Hall, 1996, pp 1–527. [Google Scholar]

- Odewunmi N. A.; Umoren S. A.; Gasem Z. M.; Ganiyu S. A.; Muhammad Q. L-Citrulline: An Active Corrosion Inhibitor Component of Watermelon Rind Extract for Mild Steel in HCl Medium. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 51, 177–185. 10.1016/j.jtice.2015.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onawole A. T.; Popoola S. A.; Saleh T. A.; Al-Saadi A. A. Silver-Loaded Graphene as an Effective SERS Substrate for Clotrimazole Detection: DFT and Spectroscopic Studies. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 201, 354–361. 10.1016/j.saa.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães L.; de Abreu H. A.; Duarte H. A. Fe(II) Hydrolysis in Aqueous Solution: A DFT Study. Chem. Phys. 2007, 333, 10–17. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2006.12.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Abreu H. A.; Guimarães L.; Duarte H. A. Density-Functional Theory Study of Iron(III) Hydrolysis in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 7713–7718. 10.1021/jp060714h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T.; Kobayashi R.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01. Gaussian, Inc.Wallingford, CT, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. Molecular Modeling Basics, 1st ed.; Boca Raton, CRC Press: 2010; pp 1–189. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi A. E.; Comba P.; McGrady J.; Lienke A.; Rohwer H. Electronic Structure of Bispidine Iron(IV) Oxo Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 6420–6426. 10.1021/ic700429x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühl M.; Reimann C.; Pantazis D. A.; Bredow T.; Neese F. Geometries of Third-Row Transition-Metal Complexes from Density-Functional Theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 1449–1459. 10.1021/ct800172j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milman V.; Winkler B.; White J. A.; Pickard C. J.; Payne M. C.; Akhmatskaya E. V.; Nobes R. H. Phase Stability of Inorganic Crystals : A Pseudopotential Plane-Wave Study. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2000, 895–910. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]