Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study is to quantify and identify characteristic vibratory motion in typically developing prepubertal children and young adults using high-speed digital imaging.

Method:

The vibrations of the vocal folds were recorded from 27 children (ages 5–9 years) and 35 adults (ages 21–45 years), with high speed at 4,000 frames per second for sustained phonation. Kinematic features of amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, phase asymmetry, spatial symmetry, and glottal gap index were analyzed from the glottal area waveform across mean and standard deviation (i.e., intercycle variability) for each measure.

Results:

Children exhibited lower mean amplitude periodicity compared to men and women and lower time periodicity compared to men. Children and women exhibited greater variability in amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, phase asymmetry, and glottal gap index compared to men. Women had lower mean values of amplitude periodicity and time periodicity compared to men.

Conclusion:

Children differed both spatially but more temporally in vocal fold motion, suggesting the need for the development of children-specific kinematic norms. Results suggest more uncontrolled vibratory motion in children, reflecting changes in the vocal fold layered structure and aero-acoustic source mechanisms.

Keywords: endoscopy, voice, children

Direct measurements of source characteristics of vocal fold vibrations in the pediatric population remain understudied in the field of voice science. The literature thus far on pediatric voice development consists of indirect measurements of vocal fold vibrations, such as acoustics, aerodynamics, and electroglottographic measurements. Though useful for intrasubject comparisons and assessment of either treatment outcome or severity of disease progression (Kent, 1976), the “score” from acoustic, aerodynamic, and electroglottography measures provides only indirect estimates of actual vocal fold motion. Because of the multidimensional glottal morphology with lateral, anteriorposterior, and superior-inferior movements, typically the score from indirect measurements does not provide information of the source characteristics required to ascertain the nature of the vocal disturbance.

Visualization of vocal fold vibratory patterns, using methods of laryngeal imaging, is fundamental to appropriate diagnosis and treatment of pediatric voice disorders. Clinically, stroboscopy is the current gold standard in laryngeal imaging. Routine clinical practice in the pediatric population uses norms from the adult population. The adult model is not suitable for evaluating vocal fold vibratory motion in children because there are substantial differences between the immature layered structure of pediatric vocal folds and the matured layered structure of adult vocal folds. At birth, the vocal folds in children predominantly present a monolayered structure composed of the epithelium; adult vocal folds present a trilayered structure that consists of the epithelium, lamina propria, and the muscle (Hirano, Kurita, & Nakashima, 1983). During the developmental period, the layered structure of the vocal fold approximates the adult trilaminar structure at a differential rate. By age 7 years, the prepubertal size of the pediatric superficial lamina propria approximates that of the adult superficial lamina propria, whereas by age 10 years, the depth of the lamina propria approximates that of the adult (Boseley & Hartnick, 2006); however, its elastin and collagen fiber compositions are not present until age 13 years (Hartnick, Rehbar, & Prasad, 2005). The authors concluded that the classic adult composition of the layered structure of the vocal fold is not adequate to describe the layered structure of the vocal folds of children (Hartnick et al., 2005). As with the differential rate of maturation of the vocal fold layered structure, there are known size differences of the vocal fold length (Hirano et al., 1983), laryngeal cartilages (Kahane, 1978, 1982), and the vocal tract (Vorperian et al., 2011). The impact of the immature and changing morphological differences of the vocal folds on vocal fold kinematics during the developmental process has not been addressed. It is logical to hypothesize that the morphological differences in the vocal folds of children would result in differential vocal fold kinematics.

High-speed imaging, with its increased temporal resolution, quantifies clinically relevant kinematic features (Deliyski & Hillman, 2010; Inwald, Döllinger, Schuster, Eysholdt, & Bohr, 2011). Unlike stroboscopy, high-speed imaging can be used for visual as well as for quantitative assessment of vocal fold motion for phonation samples of less than 2–3 s. Because of children’s variability in attention span and participation (Wolf, Primov-Fever, Amir, & Jedwab, 2005), it is often difficult to obtain the phonation samples of greater than 3–4 s required for stroboscopic recording (Hertegard, 2005), resulting in noninterpretable findings from the failure of a strobe light to track vibratory motion due to instrumental artifacts. High-speed imaging appears to be ideal for visual as well as for quantitative assessment of vibratory motion in the pediatric population (Patel, Dixon, Richmond, & Donohue, 2012; Patel, Donohue, Johnson, & Archer, 2011). Numerous recent studies have quantified vibratory asymmetries with the use of high-speed digital imaging (HSDI) in adults. Mehta, Deliyski, Quatieri, and Hillman (2011) quantified three types of left-right vocal fold asymmetries in amplitude, phase, and axis shift related to the mediolateral distance in adults for normal and pressed phonation and found that the asymmetries were observed in adults without vocal fold pathology. Similarly, Bonilha, Deliyski, and Gerlach (2008) subjectively observed left-right asymmetries ranging from 0 to 20% and quantified in normal phonation in 52 subjects. Similar asymmetries of up to 20% were reported by Wurzbacher et al. (2006) in 10 healthy subjects during glissando. Varying open-close timing characteristics and glottal area perturbation within normal phonation in adults were reported by Ahmad, Yan, and Bless (2012) from high-speed analysis using the Hilbert transform. Qiu, Schutte, Gu, and Yu (2003) quantified vibratory motion on videokymography at 7,812.5 frames per second, which showed slight differences in the amplitude symmetry index but revealed perfect time periodicity and phase asymmetry in a total of three subjects. Using a method of Fourier image analysis, Krenmayr, Wollner, Supper, and Zorowka (2012) reported left-right phase difference of an average of 15° in 11 subjects with normal voice. They also noted anterior-posterior phase differences in normal subjects similar to Bonilha et al. (2008). Piazza et al. (2012) quantified the ratio between the amplitude of the vocal folds, the ratio between two successive periods, and the ratio between the duration of the open and closed phase within a glottal cycle using videokymographic images and revealed that the amplitude and period were both around 1, whereas the ratio of the open/closed quotient was 1.35 for 18 normal subjects, indicating that the duration of the open phase of the glottal cycle is always longer than the closed phase. Similar data quantifying vocal fold periodicity and symmetry are lacking in the pediatric population.

Models of normal vocal fold physiology and age-specific norms in children are crucial for early identification and intervention. Incidence of chronic hoarseness in children is estimated from 2% (Wilson, 1987) to 23.4% (Silverman, 1975), resulting in a long-lasting negative impact on children both psychologically (Connor et al., 2008; Lass, Ruscello, Bradshaw, & Blankenship, 1991) and academically (Ruddy & Sapienza, 2004). Voice disorders often result in disruption of one or more of the following vibratory features: periodicity of motion, amplitude of vibration, vocal fold symmetry, glottal gap, and mucosal wave (Bless, Hirano, & Feder, 1987). However, studies of vibratory motion in children due to either voice disorder or the normal developmental process are lacking. Quantitative measurement of vibratory function is critical for the assessment and the development of empirically based age-specific clinical and multimass biomechanical models (Döllinger et al., 2002; Wurzbacher et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010) to be used for early identification of voice disorders in children. Data from quantitative measurements of vibratory function obtained from high-speed imaging may provide the basis for evaluating vibratory motion in the pediatric population. Therefore, the vibratory features of periodicity, symmetry, and insufficiency were selected for this study because these features are frequently used for visual assessment of vibratory motion in routine clinical practice (Bless et al., 1987; Inwald et al., 2011).

The specific purpose of this prospective study is to elucidate the nature of age-related kinematic differences in vocal fold periodicity, symmetry, and glottal gap index between children and adults. It was hypothesized that children will have reduced mean glottal periodicity, glottal symmetry, and glottal gap index compared to adults. Given the unique nature of the layered structures of the vocal folds and the differential aerodynamic and acoustic characteristics in children, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that the resulting vibratory dynamics also might undergo significant changes during childhood based on the body-cover theory (Hirano, 1974) and the source-filter interactions (Fant, 1960). Moreover, examining this hypothesis is critical to understanding the development of vibratory motion and establishment of children-specific norms.

Method

Participants

Adult and children participants were recruited from advertisements and fliers that were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) and placed around the University of Kentucky campus and at the University of Kentucky Children’s Hospital. A total of 49 children (ages 5–9 years) and 37 adults (ages 21–45 years) participated at the University of Kentucky’s Vocal Physiology and Imaging Laboratory after signing appropriate IRB-approved informed consent and assent forms. Participants were included in the study if they met the following criteria: had negative histories of vocal pathology, were not professional voice users, and were perceptually judged to have a normal voice by a certified speech language pathologist specializing in voice disorders. Children experiencing puberty as determined by case history were excluded from the study, as were adults with a history of smoking. None of the children in the study had voice change or overt physical changes associated with puberty. Data from 17 children and one adult could not be obtained because of heightened gag reflex. The researchers excluded five children and one adult from the study because 50 cycles of steady phonation at normal pitch and loudness could not be obtained from them. Hence, data from 27 children and 35 adults were subjected to further analysis (Table 1). The images included in this study were of good quality with good visibility of the glottal area, minimal movement of the glottis for the selected segment, and no oversaturation on the epiglottis.

Table 1.

Participant groups and age summary of mean and standard deviations.

| Variable | Men | Women | Children |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||

| Number | 16 | 19 | 16 | 11 |

| Mean age (yrs) | 29 ± 8 | 28 ± 7 | 6 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 |

High-Speed Digital Imaging

Sustained phonation on the vowel /i/ was recorded at participants’ typical pitch and loudness. The recordings were performed by a digital grayscale KayPENTAX high-speed system, Model 9710, with a sampling rate of 4,000 frames per second and a spatial resolution of 512 × 256 pixels for a maximum duration of 4.094 s. The camera was coupled to a 70° KayPENTAX endoscope with a xenon light source of 300 W. A simultaneously recorded acoustic signal, recorded at 50 kHz, was used to confirm the presence of steady-state phonation and participants’ task performance of typical pitch and loudness. Participants performed three practice trials of sustained phonation on the vowel /i/ at typical pitch and loudness prior to recording with HSDI. After practice, three trials were recorded for each participant. Only one representative sample of typical phonation per participant was analyzed.

Data Segmentation and Parameter Extraction

Image segmentation (Lohscheller, Toy, Rosanowski, Eysholdt, & Döllinger, 2007), extraction, and computation of parameters were performed by using a custom software application (glottal analysis tools, or GAT), which was developed at the Department for Phoniatrics and Pediatric Audiology, Erlangen, Germany. Prior to data segmentation of the high-speed videos, the data from all participants were verified for task performance, based on acoustic analysis of sustained phonation on the vowel /i/. From each high-speed recording, a sequence of steady-state phonation of 50 oscillation cycles (160–460 ms corresponding to 110–310 Hz fundamental frequency) was selected and analyzed. The criterion of a minimum of 50 oscillation cycles of steady-state phonation was defined empirically and has been used successfully in a previous study (Döllinger, Dubrovskiy, & Patel, 2012). As the duration increases, the distance between the tip of the endoscope varies as well, which could further influence the analysis of vocal fold vibratory motion. Hence, the duration of 50 cycles of steady-state phonation was considered a reasonable compromise to the maximum sample size to obtain a reliable/valid data sample. The pitch trace, root-mean-square (RMS) amplitude contour, and wideband spectrogram on TF32 (Milenkovic, 2003) acoustic software analysis program were used to guide the segmentation of steady-state phonation. The acoustic tracings were examined both visually and quantitatively for a 20-Hz shift in a 20-ms window for steady-state phonation (Kent, Kent, Weismer, & Martin, 1989). The mean fundamental frequency was 251 Hz (SD = 31 Hz) for women, 145 Hz (SD = 36 Hz) for men, 295 Hz (SD = 31 Hz) for boys, and 275 Hz (SD = 31 Hz) for girls.

A region-growing approach (Lohscheller et al., 2007) was used for image segmentation. Seed points were manually set into the open glottis (dark gray values), and all pixels below a defined threshold were considered part of the glottal area. The boundary of the detected glottal area represented the vocal fold edges, and the summation of the considered pixels for each frame over time resulted in the glottal area waveform (GAW). For each period, the video frame with the most open state of the glottis was computed (i.e., maximum GAW). In these frames, the positions of the dorsal and ventral endings of the glottis were automatically computed (Lohscheller et al., 2007). Between these frames, the dorsal and ventral positions were linearly interpolated and the glottal midline was computed between these positions (Inwald et al., 2011; Lohscheller et al., 2007). The applied methods for computing the dorsal and ventral endings are based on the principal component analysis (PCA) (Pearson, 1901). The border points of the segmented glottal area (i.e., vocal fold edges) form a point-set in the two-dimensional space; hence, two main directions can describe the spatial orientation. These two main directions can be computed by PCA, with the assumption that the longitudinal extent (first component) is larger than the lateral extent (second component) of the glottis. Within the PCA, the center point of reference plays an important part because it is the origin of the new transformed coordinate system for which the spatial orientation of the point-set are computed. The anterior point is computed using two methods:

Most deep: The anterior point is taken as the deepest point of the segmented glottis contour in the frame.

Dynamics of the second component of PCA: The anterior point is the projection along the first PCA of the midpoint of the center of the line having the largest distance between the left and right glottis contour.

The computation of the glottal midline and the posterior point is achieved by the following three approaches:

Anterior-posterior line: The posterior line is considered to be the highest point of the segmented glottis contour. The connecting line is the glottal midline.

Anterior point–PCA: The direction of the glottal midline is computed as the first PCA component with the anterior point as a reference point for the PCA

Center of glottis–PCA: The direction of the glottal midline is computed as the first PCA component with the center of mass of the glottis contour as reference point for the PCA.

For approaches 2 and 3, the posterior point is the intersection of the glottal midline and glottal contour in the dorsal area.

However, because of the possibility of occlusion of the posterior areas of the larynx, and because of the diversity of the glottal area geometry based on left-right dynamic asymmetry, it is not possible to apply one correct method to determine the glottal midline or glottal axis. Hence, we applied all three methods for computations of the dorsal and ventral positions and glottal midline in this data set. The analysis program automatically selected the best method for the most appropriate midline for a particular video. A human observer also verified each video for the accuracy of the automated midline selection by visual observation. The automated selection of the midline based on human visual verification was accurate 100% of the time. To verify the midline selection, the human observer manually selected the various options for the midline—visually judging them to verify the best option for the midline—during the most open phase of the glottal cycle.

For each subject the following five parameters were computed for data analysis: (a) amplitude periodicity, (b) time periodicity, (c) phase asymmetry, (d) spatial symmetry, and (e) glottal gap index. Means as well as the standard deviations (marked by “_SD”) were computed for each parameter. The standard deviations correspond to the regularity or intercycle variability of the vocal fold vibrations. That is, the closer the SD values are to zero, the more periodic the vibration.

Glottal Periodicity

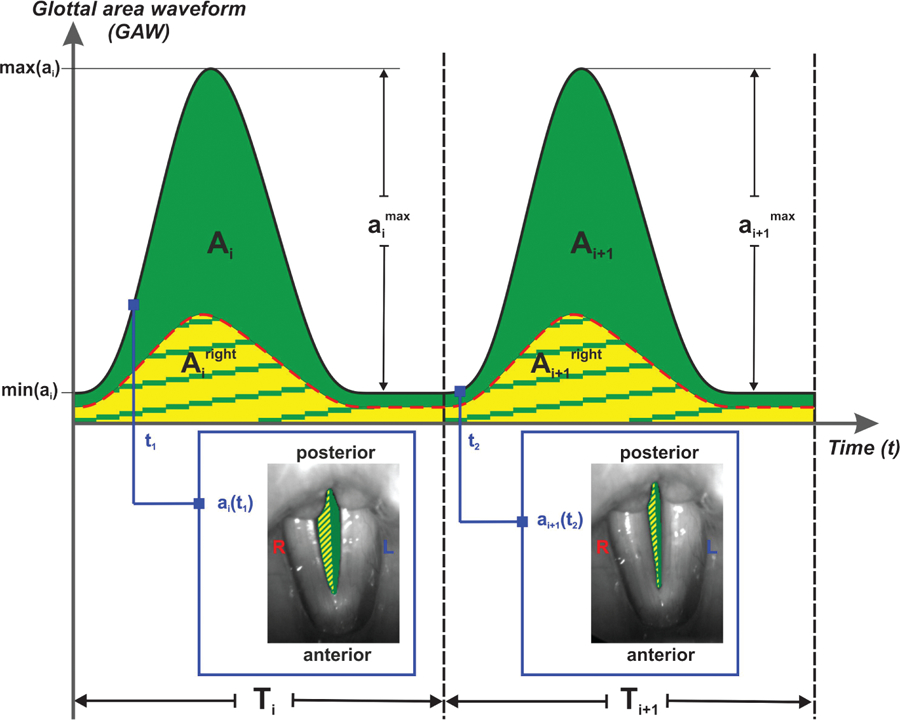

Amplitude periodicity.

Amplitude periodicity (Figure 1) was defined as the average of the quotient between the smaller and larger area amplitudes amax between two successive cycles i and i+ 1:

| (1) |

This is similar to the amplitude periodicity computed by Qiu et al. (2003); however, the formula here was applied to the GAW generated from high-speed imaging rather than from digital kymography, as in Qiu et al. (2003). Values closer to 1 indicate perfect cycle-to-cycle periodicity in the glottal area amplitude, whereas values closer to 0 indicate large cycle-to-cycle changes in the amplitude of the GAW. Amplitude periodicity can be considered similar to the acoustic measurement of shimmer for the glottal area function.

Figure 1.

Visualization of calculation of glottal gap index, time periodicity, amplitude periodicity, and spatial symmetry. Ai refers to integration of glottal area over the duration of a period i, ai(ti) refers to area for frame i in cycle i, and Ti refers to time of cycle i.

Time periodicity.

Time periodicity (Figure 1) was defined as the quotient between the duration of two successive cycles, that is, shorter duration of both cycles divided by the longer duration:

| (2) |

Ti is the time for cycle i. Values closer to 1 indicate that the cycle duration is periodic, whereas values closer to 0 indicate cycle-to-cycle aperiodicity (Qiu et al., 2003). Time periodicity can be viewed comparable to jitter for the glottal area function.

Glottal Symmetry

Phase asymmetry.

Glottal phase asymmetry was computed by subtracting the time of maximum glottal area of the left side from the time of maximum glottal area of the right side per cycle (Qiu et al., 2003). The time difference was normalized using the length of the glottal cycle. To enable group comparisons, the absolute values were considered:

| (3) |

N is the number of considered cycles and i the actual cycle. The value of 0 indicates complete glottal phase asymmetry between the right and the left vocal folds, whereas a value of 1 indicates complete phase symmetry between the left and the right vocal folds with respect to the glottal midline.

Spatial symmetry.

Ai is the overall frames within cycle i, which is the integration of the glottal area over the duration of a period., are the overall frames within cycle i, summarized as the right or left glottal area, that is, right or left of the glottal midline. Spatial symmetry (Figure 1) was computed as follows:

| (4) |

The value of 0 indicates symmetry between the left and the right parts of the glottal area. However, there could still be phase asymmetry, since for spatial symmetry, the GAW is integrated over one entire oscillation cycle and, hence, does not consider the progress of the GAW itself. However, the GAW progress is considered in phase asymmetry, where the time points of maximum left and right glottal area are subtracted from each other. The value of 1 indicates that one vocal fold remains at midline (left or right glottal area is zero).

Glottal Gap Index

Glottal gap index (Figure 1) was computed by dividing the minimum glottal area, min(ai), by the maximum glottal area, max(ai), for period i and then by averaging over all cycles, N, as outlined in Kunduk, Döllinger, McWhorter, and Lohscheller (2010):

| (5) |

Values can range from 0 to 1 (Kunduk et al., 2010). Large values indicate less change in glottal area, whereas small values close to 0 indicate large vibrational changes as well as complete glottal closure.

These parameters were computed for every cycle for the sample size of 50 cycles. Both mean and standard deviation values (within-subject variability) across all cycles were used to quantify vibratory motion, resulting in a total of 10 parameters.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was performed to test for normality of the 10 dependent variables. Based on the type of data distribution, t test (normal distribution) and Mann–Whitney U test (nonnormal distribution) were used to compare two age groups in children (children <8 years and children ≥8 years) and gender in children (boys and girls). Parameter means of time periodicity, phase asymmetry, and spatial symmetry were normally distributed for the two age groups in children.

Group differences between the three groups (men, women, and children) were compared using a Kruskal–Wallis test with Bonferroni correction with a significance level of p ≤ .005 (=.05/10), since all 10 parameters revealed a nonnormal distribution. Post hoc comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test only for parameters that were statistically significant between the three groups. Significance level for post hoc tests was p = .05. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software Version 21.

Results

None of the variables or their standard deviations varied significantly between the two age groups in children (children <8 years and children ≥8 years) and between boys and girls; therefore, the two age groups and boys and girls were combined into one group called “children” when comparing children with adults for further analysis. There was a statistically significant effect of participant groups for the means of the dependent variables amplitude periodicity, p < .001, and time periodicity, p < .001. Statistical significance was not obtained for phase asymmetry, p = .015; spatial symmetry, p = .054; and glottal gap index, p = .02 between the three considered groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

The mean of the dependent variables across three groups: women, men, and children (ages 5–9 years).

| Dependent variable | Women n = 19 |

Men n = 16 |

Children n = 27 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Amplitude Periodicity_Mean* | .977 | .009 | .985 | .003 | .967 | .019 |

| Time Periodicity_Mean* | .954 | .024 | .973 | .011 | .945 | .027 |

| Phase Asymmetry_Mean | .033 | .023 | .048 | .041 | .077 | .057 |

| Spatial Symmetry_Mean | .158 | .091 | .154 | .102 | .258 | .180 |

| Glottal Gap Index_Mean | .054 | .072 | .006 | .015 | .051 | .057 |

Note. Significant group differences are indicated by an asterisk.

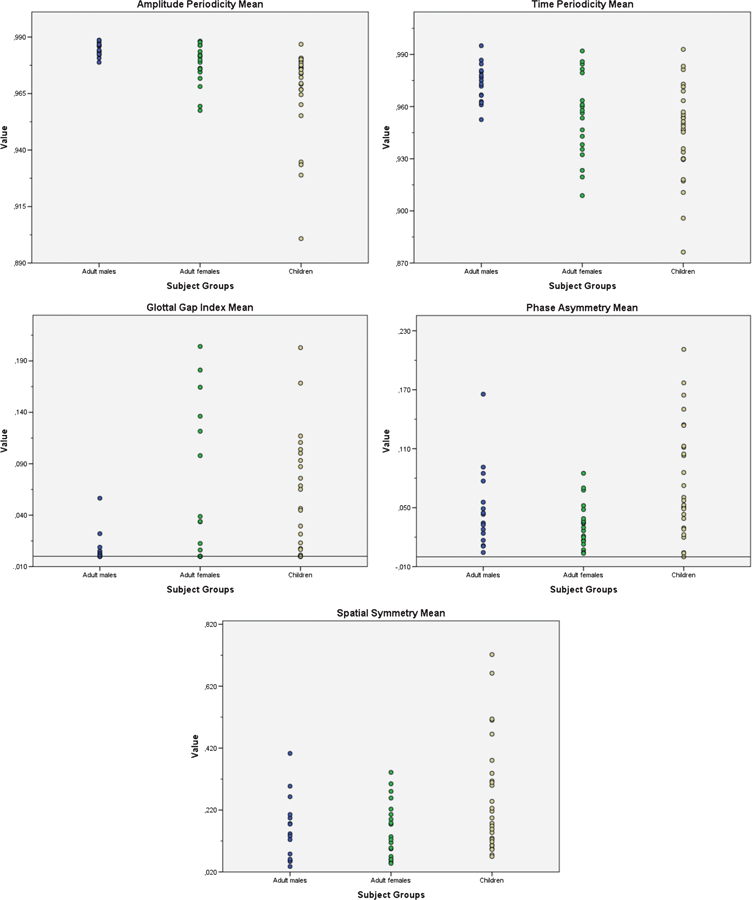

Pairwise comparison with the Mann–Whitney U test revealed that children had significantly lower mean amplitude periodicity (M = .967, SD = .019) compared to men, U = 18.5 (M = .985, SD = .003), and women, U = 154 (M = .977, SD = .009) (Tables 2 and 4). Typically developing children had significantly lower mean time periodicity, U = 68 (M = .945, SD = .027), compared to men (M = .973, SD = .011). Children did not differ significantly in time periodicity, U = 208.5, compared to women (M = .954, SD = .024) (Figure 2). Men had statistically larger values of amplitude periodicity, U = 64, and time periodicity, U = 76, compared to women (Table 2).

Table 4.

Results from post hoc analysis comparing the three groups of children (n = 27), women (n = 19), and men (n = 16).

| Parameter | Women vs. men | Women vs. children | Men vs. children |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post hoc: Mann–Whitney U ( p < .05) | |||

| AmplitudePeriodicity_Mean | 0.004 | 0.022 | .000 |

| AmplitudePeriodicity_Std | 0.003 | 0.067 | .000 |

| TimePeriodicity_Mean | 0.012 | 0.284 | .000 |

| TimePeriodicity_Std | 0.007 | 0.144 | .000 |

| GlottalGap Index_Mean | — | — | — |

| GlottalGapIndex_Std | 0.027 | 0.182 | .001 |

| PhaseAsymmetry_Mean | — | — | — |

| PhaseAsymmetry_Std | 0.003 | 0.101 | .000 |

| SpatialSymmetry_Mean | — | — | — |

| SpatialSymmetry_Std | — | — | — |

Note. Significant results of the pairwise comparisons are depicted in boldface.

Figure 2.

Dot plots of mean values of amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, glottal gap index, phase asymmetry, and spatial symmetry across men, women, and children. Mean values per subject were computed across 50 cycles.

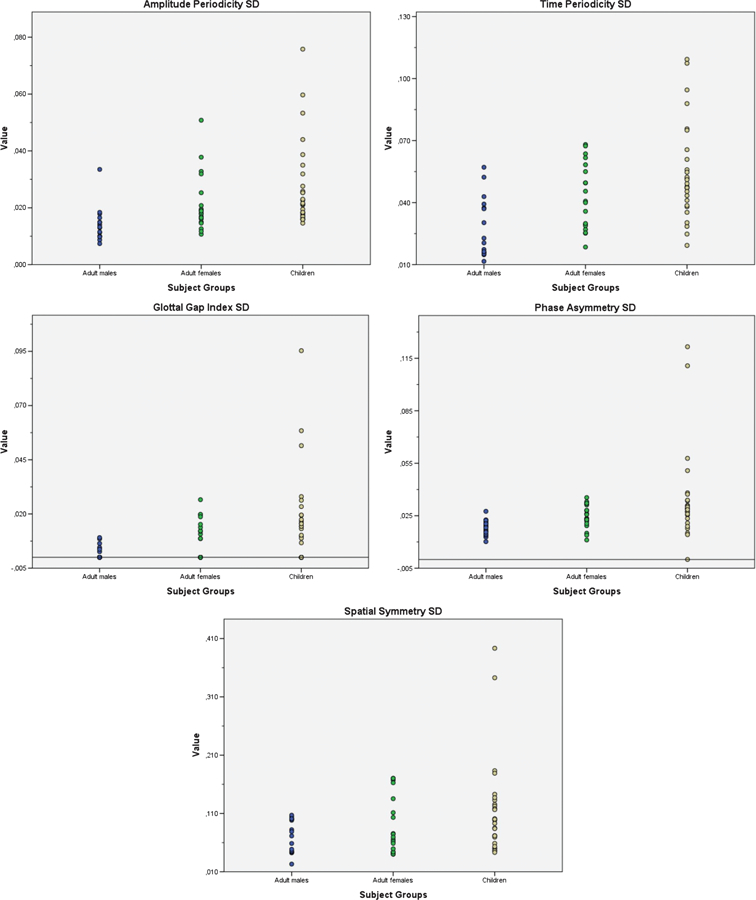

To investigate the variability within the data set and to assess the potential differences between the three participant groups (men, women, and children), the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed for the standard deviations of means for the dependent variables of amplitude periodicity_SD, time periodicity_SD, phase asymmetry_SD, spatial symmetry_SD, and glottal gap index_SD. There was a significant effect of participant groups for the standard deviations of the dependent variables of amplitude periodicity_SD ( p < .001), time periodicity_SD ( p < .001), phase asymmetry_SD ( p < .001), and glottal gap index_SD ( p = .003). The variation of spatial symmetry, p = .098, was not statistically significant across the three groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dot plots of standard deviation values of amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, glottal gap index, phase asymmetry, and spatial symmetry across men, women, and children. Standard deviation values per subject were computed across 50 cycles.

Post hoc analysis with Mann–Whitney U test revealed that children exhibited significantly greater variability in amplitude periodicity_SD, U = 44; time periodicity_SD, U = 66; phase asymmetry_SD, U = 68; and glottal gap index_SD, U = 91, compared to adult males (Tables 3 and 4). Similarly, post hoc analysis with Mann–Whitney U test revealed that women exhibited significantly greater variability in amplitude periodicity_SD, U = 61.5; time periodicity_SD, U = 70; phase asymmetry_SD, U = 61.5; and glottal gap index_SD, U = 91, compared to men (Tables 3 and 4). However, women did not differ from children on amplitude periodicity_SD, U = 174.5; time periodicity_SD, U = 191; phase asymmetry_SD, U = 183; and glottal gap index_SD, U = 198.

Table 3.

The standard deviation (SD) of the dependent variables across three groups: women, men, and children (ages 5–9 years).

| Dependent variable | Women n = 19 |

Men n = 16 |

Children n = 27 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Amplitude Periodicity_SD* | .021 | .010 | .014 | .006 | .027 | .015 |

| Time Periodicity_SD* | .043 | .016 | .028 | .015 | .055 | .024 |

| Phase Asymmetry_SD* | .024 | .007 | .018 | .004 | .035 | .026 |

| Spatial Symmetry_SD | .089 | .049 | .072 | .028 | .115 | .083 |

| Glottal Gap Index_SD* | .009 | .009 | .002 | .003 | .017 | .021 |

Note. Significant group differences are indicated by an asterisk.

Discussion

The present study used quantitative assessment of vibratory motion to reveal unique kinematic characteristics of glottal periodicity, glottal symmetry, and glottal gap index in typically developing prepubertal children compared to adults. First, findings from this direct physiological study of vocal fold vibrations in typically developing children suggest that reduction in vocal fold periodicity and high cycle-to-cycle variability in periodicity, phase symmetry, and glottal gap index are general kinematic phenomena associated with prepubertal vocal fold motion. Hence, for clinical assessment of vibratory function, the presence of reduced periodicity and increased cycle-to-cycle variability in children should be evaluated with caution, as these may not indicate vocal fold abnormality in the absence of true vocal fold abnormalities. Future large-scale studies that investigate the normative ranges for age cohorts are required. Spatial symmetry in children was similar to that of adults.

Kinematic Differences in Vibratory Motion Between Typically Developing Children and Adults

The study revealed that the vocal fold motion in children was characterized by reduced amplitude periodicity compared to men and women (Figure 2). Even though the children in this study exhibited lower mean amplitude periodicity when compared with women and men, the variability in amplitude periodicity was similar to women. Children only demonstrated greater variability in amplitude periodicity when compared to men (Figure 3). This finding of greater variability in amplitude periodicity in children is in part supported by our previous study, where in vivo measurement of vibratory amplitude in one man, woman, and child, performed using a two-point laser endoscope, also revealed large peak-to-peak amplitude changes (Patel et al., 2011). Vibratory amplitude in the child was smaller with increased peak-to-peak variability in amplitude (.29 ± .06 mm) compared to the man (.88 ± .03 mm) and the woman (.80 ± .04 mm) (Patel et al., 2011). The current findings, though not from actual physical measurements of vibratory amplitude in millimeters, are from a large number of subjects compared to a single subject from the previous study. The semiautomated image processing method used in this article, though robust, requires human interface to place and adjust the seed points to track the vocal fold margins and for image segmentation, which could conceivably influence the estimation of vocal fold amplitude periodicity. Further, the presence of mucus, light shadows, and endoscopic angles could potentially result in measurement artifacts in estimating vocal fold amplitude periodicity. A study comparing the accuracy of the current automated image processing technique with manual segmentation using 372 high-speed recordings, captured at 4,000 frames per second, revealed high accuracy and robustness (Lohscheller et al., 2007) of the image processing technique used in this study. The automated image processing technique used in this study demonstrated high accuracy of È3 pixels for posterior and anterior portions of the vocal folds and an accuracy of 1.5 pixels for the midmembranous portion of the vocal folds compared to manual analysis (Lohscheller et al., 2007). A quantization error of 1 pixel was reported to lead to a relative error of 6.7% concerning the amplitudes of vocal fold vibrations for an assumed mean glottal width of 15 pixels. However, smaller quantization errors are expected in the current study as the images were captured at 512 × 256 pixels compared to the 256 × 256 pixels in the Lohscheller et al. (2007) study. The images used in the Lohscheller et al. (2007) study were acquired from adult subjects. Further, smaller quantization errors are expected in this study, especially for the pediatric population as the glottal width would be smaller than 15 pixels in children. The presence of amplitude aperiodicity and increased variability in amplitude periodicity were observed on visual verification of the high-speed images in children but were not subjected to empirically blinded investigation in this study. Future studies need to investigate empirically the correlation of aperiodicities quantified through methods of image processing with visual-perceptual evaluation of aperiodicites in the pediatric population.

It is speculated that amplitude periodicity may be primarily influenced by aerodynamic factors, such as lung volume, airflow, lung pressures, and viscoelastic properties of the immature body-cover relationship (Hirano, 1974). The vocal fold tissue characteristics of fewer elastin fibers and greater density of fibroblasts in children (Hirano et al., 1983) could also make it more difficult to maintain cycle-to-cycle periodicity during vocal fold vibration (Titze, 1989), resulting in different motion with glottal opening and closing. Reduced viscoelasticity of the vocal folds coupled with 50% to 100% greater lung pressures (Stathopoulos & Sapienza, 1993) distributed over small vocal folds may directly result in increased cycle-to-cycle variability in amplitude in children. Additionally, varying airflow (Stathopoulos & Sapienza, 1993), varying acoustic sound pressure level (Stathopoulos & Sapienza, 1997; Sussman & Sapienza, 1994), and greater lung volume excursions relative to the vital capacity (Hoit, Hixon, Watson, & Morgan, 1990) could also account for high variability in amplitude periodicity in children.

Children in this study also had reduced time periodicity (or increased time aperiodicity) compared to men. Similar to amplitude periodicity, the methodological caveats related to image segmentation, tracking of vocal fold margins, endoscopic angle distortions, and sampling rate could result in artifacts in estimating time periodicity. It remains to be determined whether normalizing the recording frequency between children, men, and women would result in similar findings. Time periodicity is thought to be primarily influenced by factors related to variations in fundamental frequency. Cycle-to-cycle changes in fundamental frequency could be affected by increased aerodynamic pressure when the effective vocal fold vibrating mass is smaller or if there is greater amplitude-to-length ratio (Titze, 1994). A study of five vocally normal children revealed comparable amplitude-to-length ratio in children compared to adults (Patel, Donohue, Lau, & Unnikrishnan, 2013). Hence, it can be inferred that the reduced time periodicity in children could be due to increased aerodynamic pressure in the presence of greater amplitude-to-length ratio in children. Reduced time periodicity (or increased aperiodicity) in children is direct kinematic evidence of increased jitter in children (Cheyne, Nuss, & Hillman, 1999), suggesting less control over cycle-to-cycle motion. However, the jitter in Cheyne et al. (1999) is derived from electroglottography, an indirect method of estimation of GAW (Hillman, Montgomery, & Zeitels, 1997). Contrary to the electroglottography, high-speed imaging provides direct estimation of the GAW. Changes in time periodicity may also be due to the variation in the motor control of the intrinsic muscle (Hirano & Ohala, 1969) and the immature vocal fold ligament and the cellular structures (Sato, Hirano, & Nakashima, 2001). The vocal fold ligament is not fully developed in the prepubertal ages (Kahane, 1982), which would reduce periodicity, thereby affecting the spatiotemporal features.

The results of direct measurement of reduced time and amplitude periodicity from this study should not be confused with increased perception of roughness, as a qualified speech language pathologist perceptually rated all participants in this study to have normal voice quality. Further studies on simultaneously recorded high-speed imaging and acoustic, aerodynamic, and/or electroglottographic signals are needed in the pediatric population to understand the nature and source of the aperiodicities observed in modal voice. In this study, statistical difference was not obtained in younger children as a function of age groups or gender becaue of the small sample size. It remains to be determined whether the results of time and amplitude periodicity hold true for larger sample sizes, including tests for gender differences as a function of age.

Children in this study had similar mean spatial symmetry, phase symmetry, and glottal gap index compared to adult participants, suggesting that the prepubertal children are similar to the target developmental model of the adult for vibratory characteristics of symmetry and gap index but not for periodicity. It remains to be determined whether the features of symmetry and glottal gap when derived in metric units from the GAW with the use of laser endoscopy coupled with high-speed imaging differ between children and adults, compared to the current results, which were derived in pixels rather than in metric units.

Vibratory motion in children was also characterized by greater variability in amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, phase asymmetry, and glottal gap index compared to men. Increased cycle-to-cycle fluctuations in phase asymmetry compared to men indicate the presence of left-right asymmetries, which were confirmed in spatiotemporal analysis using phonovibrogram analysis in children (Döllinger et al., 2012). Unlike the phonovibrogram analysis, the glottal waveform analysis provides quantitative information of the glottal area, which is typically observed for visual analysis of stroboscopic imaging in the clinic. Data from a recent study by Patel et al. (2012) indicate that a posterior glottal gap was the predominant configuration found in 85% of girls (n = 28) and 68% of boys (n = 28) compared to 75% of women and 54% of men. The present finding of greater variation in glottal gap index further adds to the findings of the previous study that children not only have posterior glottal gap (Patel et al., 2012) but also show variability in glottal gap index during phonation. The lack of statistical difference between children and adults for mean values of glottal gap index in this study could be due to the small sample size of a total of 27 children compared to 56 children in the Patel et al. (2012) study.

Statistical significance was not obtained between children and women for most of the kinematic features, except for amplitude periodicity. This could suggest that vocal fold vibrations in terms of reduced time periodicity and large variability in glottal periodicity, glottal gap index, and phase asymmetry in children are similar to those of women. However, it is apparent from Figures 2 and 3 that even though both children and women exhibit large variability compared to men, it appears that children are also more variable compared to women across all kinematic features. The lack of statistical significance between women and children could be due to the stringent alpha level and the small sample size. The findings here suggest that vibratory motion in children is closer if not similar to that of vocal fold motion in women. The study also provides first kinematic evidence that certain vibratory characteristics, such as spatial symmetry, are fully established during the prepubertal years, whereas some vibratory features, such as amplitude and time periodicity, are not similar to the target developmental end point of adults. Much remains to be studied in terms of the nature of the trend profile of growth versus sexual dimorphism of vocal development using a large number of subjects within each age group (e.g., ages 5, 6, and 7 years) for understanding the rate of growth and the process of change in the development of voice and voice disorders in children. One limitation of the study that needs to be addressed in future research is to track the developmental trajectory of change in vibratory periodicity, phase asymmetry, and glottal gap by empirically investigating age cohorts within each age (e.g., ages 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 years) during the prepubertal years. A positive result of future research that investigates age cohorts could explain the gender differences as a function of age during the prepubertal period. In the current study, a priori hypothesis of gender and age groups (young vs. older children) was not conducted because of reduced statistical power from the limited number of participants. Further, the lack of statistical significance between boys and girls and between children less than and greater than age 8 years validates combining the children in one group for this initial study.

Kinematic Differences in Vibratory Motion Between Vocally Normal Men and Women

Women showed reduced amplitude periodicity and time periodicity compared to men (Figure 2). Studies have reported left-right amplitude asymmetry in vocally normal adults both on quantitative analysis (Mehta et al., 2011) as well as on visual perceptual analysis (Bonilha & Deliyski, 2008) of high-speed video analysis. However, the visual and quantitative analyses in Bonilha and Deliyski (2008) and Mehta et al. (2011) were performed on digital kymographs (midmembranous section of the vocal folds) extracted from the high-speed videos recorded at 2,000 frames per second. Digital kymographs, though useful, only provide information of a selected horizontal segment along the length of the vocal fold. The current findings are from the GAW that tracks the entire glottal area compared to the midmembranous portion from the digital kymographs in Bonilha and Deliyski (2008) and Mehta et al. (2011). Moreover, the high-speed videos in this study were recorded at 4,000 frames per second for improved temporal resolution and, therefore, accuracy (i.e., more frames per vibration cycle) of measurement. The findings of gender differences in amplitude periodicity between adult participants represent the first quantitative measures of gender differences in vibratory motion.

Similar to children, women also showed increased variations in amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, phase asymmetry, and glottal gap index compared to men. Recent studies in adults have shown left-right glottal asymmetry of up to 20% in normal phonation (Bonilha et al., 2008; Wurzbacher et al., 2006); however, these studies did not report gender differences in phase asymmetry. The study by Bonilha et al. (2008) quantified left-right phase asymmetries by grouping male and female subjects using digital kymography, whereas the study by Wurzbacher et al. (2006) computed glottal asymmetries from only female subjects using a model-based classification approach and analyses from high-speed imaging.

Methodological Considerations

Accuracy and validity of objective clinical HSDI analysis depends on the spatial resolution and temporal resolution of the camera. The spatial resolution of the sensor in the clinical HSDI system used here (KayPENTAX high-speed system Model 9710 with 512 × 256 pixel resolution) is lower than that of the standard video camera (approximately 700 × 500 pixels) resolution (Wittenberg, Friedl, Völlinger, & Heppner, 2005) and likely does not cover all the necessary spatial details. Consequently, this may lead to a decreased sensitivity of the computed parameters. Such sensitivity issues may also account for the temporal resolution (4,000 frames per second) of current HSDI cameras. Finally, the frequently applied HSDI systems vary in recording rates (i.e., 2000–20000 Hz) (Echternach, Döllinger, Sundberg, Traser, & Richter, 2013) and spatial resolutions (e.g., 256 × 256 pixels, 120 × 256 pixels, 512 × 256 pixels, 1024 × 1024 pixels). This unstandardized data recording complicates the comparison of absolute computed values between different studies. These issues regarding comparability of absolute parameter values based on technical reasons was also reported for acoustic data recording and analysis (Švec & Granqvist, 2010).

Clinical Implications

This study provides preliminary evidence of reduced amplitude periodicity and time periodicity and greater variability in periodicity (amplitude and time), phase asymmetry, and glottal gap, as characteristic of normal vocal fold motion in children. These aperiodicities should not be confused with abnormal vocal fold motion. These features could serve as preliminary normative references for interpretation of vibratory motion in children. The advantages of high-speed imaging are that it captures vocal fold vibrations at a fast rate compared to stroboscopy and can be used to capture vocal fold motion in severely dysphonic children without artifacts (Patel, Dailey, & Bless, 2008). Further, the recordings obtained from high-speed imaging can be quantified. Quantification of vibratory features as proposed in this article may be critical in the future to reduce the observer-related variability in findings, thereby improving the reliability and validity of clinical assessments. Even though high-speed imaging has a lower resolution compared to acoustic analysis, the information obtained from high-speed imaging is fundamentally different from the information obtained from acoustic analysis. High-speed imaging provides direct information regarding vocal fold motion, whereas acoustic analysis is only able to provide indirect inferences regarding vocal fold motion.

Summary and Conclusions

Vocal fold vibratory motion in children is not equivalent to adult vibratory patterns scaled differently. The findings from this study emphasize the need to establish norms for the pediatric population for clinical assessment of vocal fold vibrations. Overall, the findings from this study suggest that the vocal fold vibrations in children are characterized by large glottal cycle aperiodicity both in amplitude and in time. Vocal fold motion in terms of spatial symmetry, phase asymmetry, and glottal gap in children are similar to those of adult participants; however, the vibratory motion in children is characterized by increased variability in glottal periodicity, phase asymmetry, and glottal gap. The vibratory characteristics investigated were similar between children and women, the only difference being amplitude periodicity. Greater differences were observed between vocal fold vibrations in children compared to men. Children exhibit greater amplitude aperiodicity and time aperiodicity and greater variability in amplitude periodicity, time periodicity, glottal insufficiency, and phase asymmetry compared to men. Results from this study provide preliminary norms for the pediatric population. The present study reveals a variable glottal source function in children. The interaction between a variable glottal source with increased glottal gap and the source/filter needs to be further investigated in terms of glottal vibratory features of open quotient, speed quotient, and closed quotient.

The present study has clear limitations of limited sample size and single token of normal phonation that need to be addressed in future studies. The kinematic features of this study are based on values from modal phonation in vocally normal subjects. It needs to be determined how variations in pitch and in loudness in vocally normal children and adults affect these kinematic features. The high-speed recordings alone are inherently limited, providing only two-dimensional information of vocal fold motion. The vertical component of vocal fold vibration is virtually not visible more so in children compared to adult vocal fold motion, where, during the closing phase, it is possible to view the infraglottic margin of the vocal folds, especially in men. With further studies, there may be a place for quantitative assessment of vibratory motion in routine clinical practice in the near future. Quantification of these features may result in reduced observer-related variability in findings, thereby improving the reliability and validity of clinical assessment of voice disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R03DC11360 and by the American Speech-Language and Hearing Foundation’s New Investigator Research Grant, awarded to the first author. The third author’s contribution was made possible by Deutsche Krebshilfe Grant 109204 and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft FOR894/1–2.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have declared that no competing interests existed at the time of publication.

References

- Ahmad K, Yan Y, & Bless DM (2012). Vocal fold vibratory characteristics in normal female speakers from high-speed digital imaging. Journal of Voice, 26(2), 239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bless DM, Hirano M, & Feder RJ (1987). Videostroboscopic evaluation of the larynx. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, 66(7), 289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha HS, & Deliyski DD (2008). Period and glottal width irregularities in vocally normal speakers. Journal of Voice, 22(6), 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha HS, Deliyski DD, & Gerlach TT (2008). Phase asymmetries in normophonic speakers: Visual judgments and objective findings. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(4), 367–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boseley ME, & Hartnick CJ (2006). Development of the human true vocal fold: Depth of cell layers and quantifying cell types within the lamina propria. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 115(10), 784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheyne HA, Nuss RC, & Hillman RE (1999). Electroglottography in the pediatric population. Archives of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, 125(10), 1105–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor NP, Cohen SB, Theis SM, Thibeault SL, Heatley DG, & Bless DM (2008). Attitudes of children with dysphonia. Journal of Voice, 22(2), 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliyski DD, & Hillman RE (2010). State of the art laryngeal imaging: Research and clinical implications. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 18(3), 147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döllinger M, Dubrovskiy D, & Patel R (2012). Spatiotemporal analysis of vocal fold vibrations between children and adults. The Laryngoscope, 122(11), 2511–2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döllinger M, Hoppe U, Hettlich F, Lohscheller J, Schuberth S, & Eysholdt U (2002). Vibration parameter extraction from endoscopic image series of the vocal folds. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 49(8), 773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echternach M, Döllinger M, Sundberg J, Traser L, & Richter B (2013). Vocal fold vibrations at high soprano fundamental frequencies. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 133(2), EL82–EL87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fant G (Ed.). (1960). Acoustic theory of speech production. The Hague, the Netherlands: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Hartnick CJ, Rehbar R, & Prasad V (2005). Development and maturation of the pediatric human vocal fold lamina propria. The Laryngoscope, 115(1), 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertegard S (2005). What have we learned about laryngeal physiology from high-speed digital videoendoscopy? Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 13(3), 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman R, Montgomery W, & Zeitels SM (1997). Current diagnostic and office practice: Appropriate use of objective measures of vocal function in the multidisciplinary management of voice disorders. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 5, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano M (1974). Morphological structure of the vocal cord as a vibrator and its variations. Folia Phoniatrica (Basel), 26(2), 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano M, Kurita S, & Nakashima T (1983). Growth, development, and aging of human vocal fold. San Diego, CA: College Hill Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano M, & Ohala J (1969). Use of hooked-wire electrodes for electromyography of intrinsic laryngeal muscles. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 12(2), 362–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoit JD, Hixon TJ, Watson PJ, & Morgan WJ (1990). Speech breathing in children and adolescents. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 33(1), 51–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inwald EC, Döllinger M, Schuster M, Eysholdt U, & Bohr C (2011). Multiparametric analysis of vocal fold vibrations in healthy and disordered voices in high-speed imaging. Journal of Voice, 25(5), 576–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahane JC (1978). A morphological study of the human prepubertal and pubertal larynx. Americal Journal of Anatomy, 151(1), 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahane JC (1982). Growth of the human prepubertal and pubertal larynx. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 25(3), 446–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent RD (1976). Anatomical and neuromuscular maturation of the speech mechanism: Evidence from acoustic studies. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 19(3), 421–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent RD, Kent JF, Weismer G, & Martin RE (1989). Relationships between speech intelligibility and the slope of second-formant transitions in dysarthric subjects. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 3(4), 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Krenmayr A, Wollner T, Supper N, & Zorowka P (2012). Visualizing phase relations of the vocal folds by means of high-speed videoendoscopy. Journal of Voice, 26(4), 471–479. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunduk M, Döllinger M, McWhorter AJ, & Lohscheller J (2010). Assessment of the variability of vocal fold dynamics within and between recordings with high-speed imaging and by phonovibrogram. The Laryngoscope, 120(5), 981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass NJ, Ruscello DM, Bradshaw KH, & Blankenship BL (1991). Adolescents’ perceptions of normal and voice-disordered children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 24(4), 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohscheller J, Toy H, Rosanowski F, Eysholdt U, & Döllinger M (2007). Clinically evaluated procedure for the reconstruction of vocal fold vibrations from endoscopic digital high-speed videos. Medical Image Analysis, 11(4), 400–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta DD, Deliyski DD, Quatieri TF, & Hillman RE (2011). Automated measurement of vocal fold vibratory asymmetry from high-speed videoendoscopy recordings. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 54(1), 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic P (2003). Time-Frequency Analysis for 32-Bit Windows [Computer software]. University of Wisconsin–Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Patel R, Dailey S, & Bless D (2008). Comparison of high-speed digital imaging with stroboscopy for laryngeal imaging of glottal disorders. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 117(6), 413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RR, Dixon A, Richmond A, & Donohue KD (2012). Pediatric high speed digital imaging of vocal fold vibration: A normative pilot study of glottal closure and phase closure characteristics. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 76, 954–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RR, Donohue KD, Johnson WC, & Archer SM (2011). Laser projection imaging for measurement of pediatric voice. The Laryngoscope, 121(11), 2411–2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RR, Donohue KD, Lau D, & Unnikrishnan H (2013). In vivo measurement of pediatric vocal fold motion using structured light laser projection. Journal of Voice, 27(4), 463–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson K (1901). On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Philosophical Magazine, 6(2), 559–572. [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C, Mangili S, Del Bon F, Gritti F, Manfredi C, Nicolai P, & Peretti G (2012). Quantitative analysis of videokymography in normal and pathological vocal folds: A preliminary study. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 269(1), 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Q, Schutte HK, Gu L, & Yu Q (2003). An automatic method to quantify the vibration properties of human vocal folds via videokymography. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 55(3), 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy BH, & Sapienza CM (2004). Treating voice disorders in the school-based setting: Working within the framework of IDEA. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 35(4), 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Hirano M, & Nakashima T (2001). Fine structure of the human newborn and infant vocal fold mucosae. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 110(5, Pt. 1), 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman EM (1975). Incidence of chronic hoarseness among school-age children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 40(2), 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos ET, & Sapienza C (1993). Respiratory and laryngeal measures of children during vocal intensity variation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 94(5), 2531–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos ET, & Sapienza CM (1997). Developmental changes in laryngeal and respiratory function with variations in sound pressure level. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40(3), 595–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman JE, & Sapienza C (1994). Articulatory, developmental, and gender effects on measures of fundamental frequency and jitter. Journal of Voice, 8(2), 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Švec JG, & Granqvist S (2010). Guidelines for selecting microphones for human voice production research. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(4), 356–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titze IR (1989). Physiologic and acoustic differences between male and female voices. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 85(4), 1699–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titze IR (1994). Principles of voice production. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Vorperian HK, Wang S, Schimek EM, Durtschi RB, Kent RD, Gentry LR, & Chung MK (2011). Developmental sexual dimorphism of the oral and pharyngeal portions of the vocal tract: An imaging study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54(4), 995–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK (1987). Voice problems in children (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg T, Friedl S, Völlinger H, & Heppner W (2005). High speed cameras for voice diagnosis—status quo and new perspectives. Sprache, Stimme, Gehör, 29(1), 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M, Primov-Fever A, Amir O, & Jedwab D (2005). The feasibility of rigid stroboscopy in children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 69(8), 1077–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurzbacher T, Döllinger M, Schwarz R, Hoppe U, Eysholdt U, & Lohscheller J (2008). Spatiotemporal classification of vocal fold dynamics by a multimass model comprising time-dependent parameters. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 123(4), 2324–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurzbacher T, Schwarz R, Döllinger M, Hoppe U, Eysholdt U, & Lohscheller J (2006). Model-based classification of nonstationary vocal fold vibrations. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 120(2), 1012–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Lohscheller J, Berry DA, Becker S, Eysholdt U, Voigt D, & Döllinger M (2010). Biomechanical modeling of the three-dimensional aspects of human vocal fold dynamics. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 127(2), 1014–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]