Abstract

Background:

The published literature on education about transgender health within health professions curricula was previously found to be sporadic and fragmented. Recently, more inclusive and holistic approaches have been adopted. We summarize advances in transgender health education.

Methods:

A 5-stage scoping review framework was followed, including a literature search for articles relevant to transgender health care interventions in 5 databases (Education Source, LGBT Source, MedEd Portal, PsycInfo, PubMed) from January 2017 to September 2019. Search results were screened to include original articles reporting outcomes of educational interventions with a transgender health component that included MD/DO students in the United States and Canada. A gray literature search identified continuing medical education (CME) courses from 12 health professional associations with significant transgender-related content.

Results:

Our literature search identified 966 unique publications published in the 2 years since our prior review, of which 10 met inclusion criteria. Novel educational formats included interdisciplinary interventions, post-residency training including CME courses, and online web modules, all of which were effective in improving competencies related to transgender health care. Gray literature search resulted 15 CME courses with learning objectives appropriate to the 7 professional organizations who published them.

Conclusions:

Current transgender health curricula include an expanding variety of educational intervention formats driven by their respective educational context, learning objectives, and placement in the health professional curriculum. Notable limitations include paucity of objective educational intervention outcomes measurements, absence of long-term follow-up data, and varied nature of intervention types. A clear best practice for transgender curricular development has not yet been identified in the literature.

Keywords: Medical education, transgender, gender affirmation

Introduction

Transgender populations, or those whose gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth, experience a variety of preventable health disparities.1 Drivers of these disparities include stigma from health professionals, lack of access to care, and lack of provider knowledge, among others.1-3 To combat this, health professions educators have begun developing curricula to enhance education regarding the health needs of transgender and gender non-binary individuals and reduce the stigma these individuals face when accessing care.2

There is an emerging body of literature on medical interventions to increase knowledge, attitudes, and skills around transgender clinical care.2,4,5 A previous review summarized published medical education interventions on transgender health care topics in US and Canadian medical schools and residency programs until 2017.2 This review (of whom this update shares multiple authors) noted a paucity of interventions that were transgender-specific (8 interventions) in the setting of more common general lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT)-focused educational interventions (26 interventions). A rapid acceleration in the pace of publication on this topic over the last 5 years was also observed.

Despite the trends observed in this prior review, challenges in the literature prevented robust conclusions on best practices in medical intervention on transgender health. The hurdles to robust conclusion and consensus emerged from a variety of qualities within the literature. There was considerable variation in intervention format, with some interventions being optional while others were mandatory, some being didactic lectures while others were case questions or Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE), and all with variable placement in the curriculum and target audience (eg, medical students vs residents). Lack of data on objective learning assessments further limited comparisons and determination of best practices regarding curricular development. Overall, while the topic has garnered increased attention in publications, the variety of interventions and educational outcomes documented had yet to provide clear guidance on best practices.

One limitation of this previous review is the methodology of a literature review for capturing all published guidelines, assessments, interventions, and outcomes for medical education in general. Transgender medical education is no exception, and therefore here we seek to widen the scope of items considered when reviewing this literature. Various professional organizations support the creation of educational resources to better inform medical providers about transgender health care, including the American Psychological Association (APA), American Medical Student Association (AMSA), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), American Urological Association (AUA), Endocrine Society, and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).6-14 Expanding the scope of previous literature reviews is merited given the unique nature of medical education publications on intervention and outcome data, as well as the apparent rarity of transgender medical education research.

Given the continued rapid pace of publication on transgender medical interventions, the timeliness of the topic in general, and the gaps identified in our previous literature review, we provide an update on transgender health education. We set out to identify what current education activities in health professions education curricula exist to teach about the health care needs of transgender people.

Methods

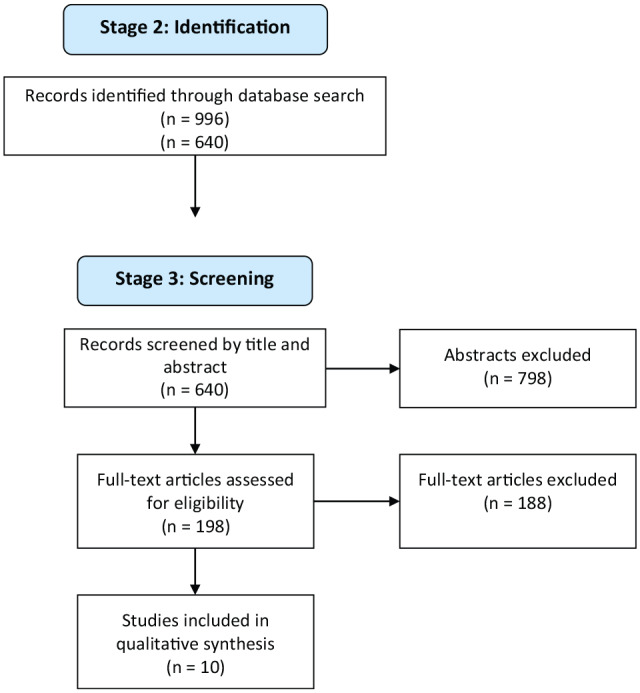

A scoping review using the 5-Stage Arksey and O’Malley framework was performed.15 Stage 1 includes identification of the research question: “What current education activities in health professions education curricula exist to teach about the health care needs of transgender people?” Stage 2 includes identification of relevant studies, which was completed via a search for articles relevant to transgender health care interventions in 5 databases (Education Source, LGBT Source, MedEd Portal, PsycInfo, PubMed) between January 2017 and September 2019. Inclusion criteria were publications that identified transgender-specific content in their educational intervention. Stage 3 includes study selection and screening, which was performed by 4 independent reviewers with inclusion criteria of original articles reporting outcomes of educational interventions with a transgender health component that included MD/DO students in the United States and Canada. Stage 4 includes data charting, which was performed by the same reviewers. Finally, stage 5 involves collating, summarizing, and reporting the results, which is the objective of this article.

To enhance our review, we performed a search of the gray literature to identify additional educational interventions outside of published literature. Web searches were performed for online curricular content on websites of professional societies representative of 12 specialties considered by the research team to be most applicable to transgender health: the APA, AMSA, AAP, ACOG, AUA, Endocrine Society, AAMC, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), the American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS), the American College of Physicians (ACP), GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality (GLMA), and the American Medical Association (AMA). We acknowledge that the health of transgender individuals may be affected by any and all medical organizations, and that other sources may also provide curricular content relevant to transgender health (eg, Fenway’s National LGBT Health Education Center provides high-quality educational information on transgender and LGBT health topics). However, we limited the scope of our gray literature search to curricular content produced by professional societies of specialties for which transgender health is the most urgent and germane. We focused on online interventions as opposed to in-person trainings given their ability to reach a wide audience and availability for readers of this review.

Results

Our literature search identified 966 unique articles, of which 10 contained transgender-specific educational interventions (Figure 1).16-25 We noted a continued acceleration of publication frequency. Previously, 8 total transgender-specific educational interventions were identified prior to December 2017. In the updated search, we identified 4 additional interventions from 2017, 3 from 2018, and 3 from 2019 (up to September) (Table 1). Results of our gray literature search included 15 online continuing medical education (CME) courses from 7 professional organizations, in the form of online articles and videos (Table 2).10-12,26-37

Figure 1.

Results of Arskey and O’Malley framework for scoping reviews, stages 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Articles identified in the scoping review published from 2017-2019.

| Authors | Audience | Intervention type | Placement in curriculum | Mandatory vs elective | Total curricular time | Transgender health topics addressed/outlined in objectives | Assessment outcomes | N for assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braun et al16 | Interdisciplinary students (dental, nursing, medicine, pharmacy) | Weekend course: Networking, Lectures, Discussion panels, OSCE |

NA | Elective | Variable within 10 hours of LGBTQI content | Transgender-specific courses include: “Trans 101: Transgender Medical Care”; “Trans 201: Transgender Medical Care.” |

Significantly improved: Subjective comfort interacting with LGBTQI patients (P < .01); Identification of relevant resources (P < .01); Confidence in conducting an accurate and inclusive medical history with an LGBTQI patient (P < .01). |

273 |

| Calzo et al17 | Interdisciplinary students | Case discussion | NA | Elective | 2.25 hours of transgender-specific case in ~8 total hours of LGBT cases | Decision-making regarding treatment and management options. | Self-rated confidence on a 1-4 scale (4 being very confident): Taking sexual health history from adolescents: from 3.3 pre-intervention to 3.2; Counseling LGBT adolescents: from 3.0 pre-intervention to 2.7; Identifying community resources for LGBT adolescents: from 2.4 pre-intervention to 3.2. |

10 |

| Marshall et al18 | Medical students | Lecture, Mock Patient Interview | Endocrinology block | Mandatory | 3.5 hours | Didactic: Terminology; Medical and surgical interventions; Cause of potential complications hormone therapy; Approach to addressing health care needs of transgender patients; Health disparities faced by transgender patients. Patient encounter: Examples of a primary complaint of a patient with gender dysphoria; Language to inquire about the gender identity of a patient, Appropriately addressing transgender patients; Describe interprofessional resources available to patients with gender dysphoria. |

73% felt more prepared to care for transgender patients than before, 26% felt equally as prepared. | 85 |

| Cherabie et al19 | Medical students, Residents, Licensed Physicians | Lecture, Patient presentation |

NA | Elective | 1 hour | Attitudes, comfort level, knowledge, and beliefs regarding treatment of trans people; Personal accounts of transgender patients regarding their transition. |

Self-reported beliefs, attitudes, comfort, and knowledge measured on 1-5 scale immediately pre- and post-intervention, and at 90 days: Beliefs: 2.68 pre, 2.74 post, 2.81 90 days; Attitudes: 2.62 pre, 4.12 post, 4.00 90 days; Comfort: 2.54 pre, 3.42 post, 3.26 90 days; Knowledge: 2.36 pre, 3.74 post, 3.37 90 days. |

163 |

| Davidge-Pitts et al20 | Endocrinology fellows | Lecture, Case discussion |

Educational conference | Elective | 2 hours | Curricula content of training programs; Fellows’ perception of confidence in key areas of trans health care. |

Significant increase in self-rated comfort regarding: Knowledge of identity and relationship terminology (58.3% to 88.4%, P < .001); Comprehensive gender-oriented history (47.4% vs 77.9%, P < .001); Physical examination (29.2% vs 63.3%, P < .0001); Organ-specific screening recommendations (39.1% vs 76.1%, P < .0001); Psychosocial and legal issues (20.8% vs 51.1%, P < .0001). |

181 |

| Park and Safer24 | Medical students | Clinical rotation (Primary care, Pediatrics, Endocrinology, and Surgery) | Fourth-year medical students | Elective | 1 month | Medical students’ attitudes and level of overall preparedness in providing care for transgender patients. | Self-reported “high” comfort increased from 45% (9/20) to 80% (P = .04); Self-reported “high” knowledge regarding management of transgender patients increased from 0% to 85% (P < .001). |

20 |

| Vance et al21 | Interdisciplinary students (NP, MS4’s), Pediatric interns, Psychiatry interns | Online didactic modules | NA | Elective | 2 hours | Terminology, background; Taking a gender history and psychosocial history; Performing a physical examination and pubertal staging; Formulating an assessment and psychosocial plan; Counseling on pubertal blockers and gender-affirming hormones. |

Overall objective knowledge scores increased from 22% to 56% (P < .001); Self-perceived knowledge scores increased from 1.8 to 3.8 (P < .001, Scale 1-5); Self-efficacy scores increased from 3.5 to 7.0 (P < .001, Scale 1-10). |

28 |

| Click et al22 | Medical students | Mixed: Case presentation, Lecture, Patient interview, Small group discussions, Patient Q/A |

First- and second-year medical students | Mandatory | Half day | Didactic: Basic terminology; Electronic health record; Patient interview; Hormone therapy; Sex differentiation; Action of steroid hormones. Small group discussions: Uncomfortable situations; Planning and practicing a patient interview; Creating safe environment; Overcoming personal bias; Building the health care team. |

Immediately post-intervention, objective knowledge scores improved for: Anatomy-based cancer-screening protocols; Common hormone therapy regimens and their respective side effects. At 2-month follow-up (n = 85), learners: Felt comfortable asking patients about gender identity (78%); Believed it was appropriate to provide hormones to transgender patients (78%); Agreed transgender health belongs in general medical education (77%). |

138 |

| Encandela et al23 | Medical students | Mixed: Lecture, Discussion, Model patient |

22 components: 12 pre-clinical, 8 clinical, 2 electives (1 clinical, 1 pre-clinical) |

16 of 22 mandatory | Variable | 22 separate curriculum interventions, each with own learning objectives. Transgender-Specific Interventions Include: “Male and Female Genito-Urinary Embryology” in pre-clinical years; “Gender Dysphoria in Youth” in Pediatrics/OB/GYN block; “Family Medicine and Transgender Health Elective.” |

Implicit assumptions session: Awareness of communication strategies with transgender patients improved from 2.0 to 3.0 (P < .001, Scale 1-4). |

93 |

| Oller25 | Internal Medicine Residents | Online case modules | First-year residents | Elective | 10-15 minutes | Risks and benefits of cancer-screening; Questions to use with transgender patients when assessing the appropriateness of various cancer-screening strategies; Describe the resources available to aid shared decision making regarding cancer-screening. |

Self-rated confidence on a 1-5 scale (5 = very confident): Counseling a transgender patient about cancer-screening from 2.26 pre-intervention to 3.57; Identifying resources for transgender patients about cancer-screening: from 2.26 pre-intervention to 3.64. |

14 |

Abbreviations: LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender; LGBTQI, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex; OSCE, Objective Structured Clinical Examinations; NP, nurse practitioner.

Table 2.

Articles identified in the gray literature published from 2017-2019.

| Organization | Authors | Article title | Transgender Health Topics Addressed/Outlined in Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology | El-Saghir et al10 | Training Modules: Improving Ob/Gyn Care for Transgender and Non-Binary Individuals (CME) | Gender identity and care of transgender and gender non-conforming patients; Preventive care for transgender and gender non-conforming patients; Gender-affirming treatment and transition-related care; Common gynecologic issues among transgender patients; Health records, billing, insurance, and legal documents. |

| American Urological Association | Garcia et al11 | CME: Update Series (2017) Lesson 5: Genital Gender Affirming Surgery for Transgender Patients | Understand current commonly accepted terminology used in the care of transgender patients; Understand surgery options, staging of surgeries, postoperative complications and their management, and postoperative care pathways; Be familiar with and understand the rationale for commonly accepted care guidelines associated with transgender surgery. |

| Endocrine society | Hembree et al12 | CME—Endocrine Treatment of Gender Dysphoria/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline Educational Activity | List significant changes in the evidence base for Gender Dysphoria/Gender Incongruence since publication of the previous Endocrine Society guideline on this topic; Define significant changes in best practices that are being recommended in the 2017 Gender Dysphoria/Gender Incongruence guideline due to changes in science; Identify gaps in the existing evidence base for Gender Dysphoria/Gender Incongruence which contribute to controversy or disagreement among clinicians about standards for optimal patient care. |

| American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) | Safa et al26 | Journal CME Article: Current Concepts in Feminizing Gender Surgery | Discuss appropriate treatment guidelines, including preoperative mental health and hormonal treatment before gender-affirmation surgery; Name various surgical options for facial, chest, and genital feminization; Recognize key steps and anatomy during facial feminization, feminizing mammaplasty, and vaginoplasty; Discuss major risks and complications of vaginoplasty. |

| Deschamps-Braly et al27 | ASPS University: Gender Affirming Surgeries 101 (CME) | Understand the multidisciplinary nature of care, including the psychological evaluation and hormonal management of gender non-conforming individuals, including adolescents; Understand the Standards of Care, designed to provide flexible treatment guidelines established by The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH); Understand the historical context of gender confirmation surgery as well as the embryology and anatomy involved in gender surgery; Understand the hormonal and psychological management of gender non-conforming individuals; Understand the concepts of facial feminization and masculinization; Understand the concepts of genital surgery for transwomen and transmen; Understand common plastic surgery procedures (breast augmentation, chest contouring, and body contouring) as they relate to the gender non-conforming individuals; Understand the health policy and patient safety risks that are unique to these procedures and this patient population. |

|

| American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery | Mendelsohn et al28 | Caring for Transgender Patients: Focus on Voice Feminization: Part I and II (CME) | Identify the social and clinical challenges facing the transgender community today; Implement a vocabulary with cultural and social competency and understanding; Define a treatment strategy specific to the needs of transgender women with voice-related dysphoria and/or dysphonia. |

| El-Sayed et al29 | Cultural Competency in Your Otolaryngology Practice | Recognize how cultural sensitivity has an impact on physician-patient interactions; Develop patient rapport by use of body language that is culturally appropriate; Recall patients have the right to proper interpreters when language barriers exist; Recall statistics in health care for the transgender community Identify pronouns and other terms that are inclusive for the transgender community; Establish rapport and gain an understanding of relationships and guardianship of minors with same sex couples; Explain the relationship and consent procedures for minors with same sex couples; Become sensitive to language used with minors with same sex parents; Recognize implications of religious beliefs and their effects on medical and surgical management; Identify opportunities for improvement in communications complicated by religion and gender roles; Define unconscious bias; Identify their own unconscious bias toward culturally diverse patients; Apply this knowledge in clinical scenarios. |

|

| Mori30 | The Transgender Voice: Treatment and Surgical Techniques (CME) | Recognize the unique needs and vocal characteristics of the pretreatment and posttreatment transgender patient; Compare and explain treatment options and outcomes; Analyze the latest research in voice feminization and modification. |

|

| Chaiet et al31 | Transgender Patient Care in the Otolaryngology Practice (CME) | Learn evidence-based approaches to create LGBTQ-friendly practices and provide competent gender-affirming care; Describe the relevant surgical anatomy, necessary equipment, and pitfalls related to pitch altering phonosurgery; Understand the role of speech therapy and outline postoperative care; Understand the indications for laryngochondroplasty and facial feminization/masculinization surgery; Describe the steps of the procedures and necessary equipment and outline postoperative care. |

|

| American College of Physicians | Safer and Tangpricha36 | Care of the Transgender Patient | Terminology and initial evaluation; Medical management; Transgender-specific surgeries; Medicolegal and societal issues; Practice improvement. |

| American Medical Association | Sallans32 | Ethics Talk: Providing Compassionate Care for Transmen | Identify key ethical values or principles at stake, as described in the program; Distinguish among factors of ethical, clinical, legal, social, and cultural significance; Articulate how central themes of clinical and ethical relevance in the program can influence health care practice; Explain at least 1 way in which micro-level clinical ethics questions intersect with broader macro-level policy questions in health care. |

| Boskey et al33 | Ethics: Public Accommodation Laws and Gender Panic in Clinical Settings | Explain a new or unfamiliar viewpoint on a topic of ethical or professional conduct; Evaluate the usefulness of this information for his or her practice, teaching, or conduct; Decide whether and when to apply the new information to his or her practice, teaching, or conduct. |

|

| Canner et al34 | Temporal Trends in Gender-Affirming Surgery Among Transgender Patients in the United States | Identify the temporal trends in gender-affirming surgery; Recognize the association between payer status and the patients seeking these operations. |

|

| Bellinga et al35 | Technical and Clinical Considerations for Facial Feminization Surgery With Rhinoplasty and Related Procedures | Understand the facial surgical modifications that are performed for facial feminization surgery; Describe the surgical techniques involved in feminization of the nose. |

|

| Berli et al37 | What Surgeons Need to Know About Gender Confirmation Surgery When Providing Care for Transgender Individuals A Review |

Identify best practices for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-non-conforming people. |

Abbreviations: CME, continuing medical education; LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning.

Within these additional publications since 2017, there was considerable variation in format. This closely resembles what was described in literature prior to 2017. Formats included didactic lectures, online modules, case questions, and simulated patient encounters to improve on trainees’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills regarding transgender health care. These included interventions aimed both toward undergraduate and graduate medical education training.

Of the published interventions, 8 were targeted toward medical students to teach general topics in transgender health, 1 was targeted toward internal medicine residents, and 1 was targeted toward Endocrinology fellows. None of the articles detailed specific health concerns of non-binary patients, which was also true of our previous review.

Notable outcomes included increased presence of integrated and longitudinal curricula, interdisciplinary educational interventions including learners from other health professions alongside MD/DO learners, post-graduate interventions targeted at licensed physicians, and online courses. These are explored in depth below.

Longitudinal interventions in undergraduate medical education

Of those studies geared toward undergraduate medical students, a number reported outcomes of transgender health curricula comprising multiple educational interventions, spaced over various time periods ranging from a single day to several years.

Click et al22 reported outcomes of a half-day required educational intervention for pre-clinical students, which included a case presentation, live patient interview, small group break-out sessions, and patient Q&A sessions. Immediately post-intervention and also 2 months post-intervention, the students demonstrated improvements in multiple-choice test knowledge items such as appropriate hormone regimens and corresponding effects, an anatomy-based cancer-screening protocol. The students also self-rated increased comfort with transgender patients.

Encandela et al23 detailed 3 interventions interspersed throughout the entire medical school curriculum, including a lecture on “male” and “female” genitourinary embryology in pre-clinical period, a lecture and interactive discussion on gender dysphoria in adolescents as part of the Pediatrics clinical rotation, and an optional clinical elective titled “Family Medicine and Transgender Health Elective.” Marshall et al18 further demonstrated that transgender health care topics can be integrated into existing curriculum as they are applicable to existing curricular concepts. In a 3.5-hour intervention consisting of didactics and a mock patient interview, they introduced hormone therapy topics into existing endocrinology pre-clinical curriculum, and demonstrated increased self-rated preparedness to care for transgender patients among 85 learners.

Boston University also has a longitudinal transgender health curriculum, in which biologic evidence for gender identity is introduced in the first year, while basics of hormone therapy are taught in the second-year endocrinology/reproductive pre-clinical block, and exposure to transgender patients is encouraged during clinical years.24

Park and Safer24 demonstrated an added benefit to an elective clinical rotation on top of the existing Boston University curriculum. They reported improved self-rated knowledge, attitudes, and skills in 20 fourth-year medical students immediately after completion of a transgender-focused elective clinical rotation encompassing adult primary care, pediatrics, endocrinology, and surgery. This benefit was above the pre-intervention baseline, which reflected retained competencies gained during Boston University’s aforementioned longitudinal transgender health curriculum.

Graduate medical education interventions

Two graduate medical education interventions were noted. Oller25 exposed first-year Internal Medicine residents to an elective 10- to 15-minute online module detailing cancer-screening protocols for transgender patients as part of a 2-week ambulatory oncology block. The 14 interns who completed the modules demonstrated increased confidence in managing these concerns.

A single study reported outcomes of an educational intervention geared toward those in fellowship training.20 In this study, 198 Endocrinology fellows were exposed to a 2-hour intervention comprising 1-hour of lecture and 1-hour of case-based learning, after which they reported increased knowledge and comfort in managing endocrine concerns of transgender patients.

Interdisciplinary interventions

A few interventions targeted interdisciplinary learners by incorporating nursing, dental, nurse practitioner, and physician assistant students. Inclusion of various health profession students has been used to introduce concepts that pertain to all patient-facing practitioners, including proper ways of addressing transgender patients, cultural humility, access barriers, health disparities, and acknowledgment of community resources for transgender patients. For example, Braun et al16 targeted a 273-student mixed health professions audience in their 10-hour elective course, demonstrating improvements in self-reported confidence and comfort, and increased awareness of information resources. Calzo et al17 reported outcomes of a small cohort of interprofessional learners following 2.25-hours of trans-specific case discussion content in an 8-hour module detailing LGBT health. The case is comprised of 4 segments, which included discussions of gender identity and gender dysphoria, proper ways to address and interact with transgender patients, and treatment options for adolescents interested in gender affirmation. Although they found slightly decreased self-rated confidence in counseling LGBT adolescents (2.7 from 3.0 pre-intervention on a 1-4 scale) and taking a sexual history from them (3.2 from 3.3), they attributed these to increased recognition of the intricacies of these conversations, as qualitative conversations with participants reflected increased awareness of the role of various medical professions in caring for LGBT adolescents. Self-rated confidence identifying community resources for LGBT adolescents increased.

Interdisciplinary interventions have also been used to teach knowledge and skills relevant to multiple professional identities. For example, Vance et al21 included NP students in a web-based educational intervention that taught interviewing and cultural sensitivity skills, as well as medical knowledge–based skills such as formulating an assessment and psychosocial plan and counseling on pubertal blockers and gender-affirming hormones. They demonstrated improved knowledge and self-efficacy after this intervention, as measured by a post-intervention multiple-choice survey that assessed objective knowledge and self-assessed confidence 1 week after the intervention.

Web-based continuing medical education

One trend not noted in the previous review was an increased prevalence of transgender health care interventions geared toward licensed physicians. Education of currently practicing physicians ensures that those who have completed formal training are still able to provide appropriate care to transgender patients. In addition, it provides expertise for those who continue to educate future generations of learners. Continuation of transgender medical education past completion of residency is endorsed by the ACP and echoed by other medical organizations.38-42

Interventions geared toward practicing physicians were either published educational interventions or CME courses provided by professional societies and medical education research units. To enhance access, several professional organizations have developed online web-based CME courses.

A single educational intervention’s outcomes were published, detailing a 1-hour didactic lecture for emergency department providers, including advanced practitioners.19 Notably, this intervention was led by members of the transgender community. An immediate post-intervention survey of subjects noted that providers were more likely to (1) have increased consideration for transgender patients (49%), (2) increase screening for gender dysphoria among their patient base (22%), (3) continue their education around transgender medicine topics (16%), and (4) provide more treatment options for transgender patients (13%). These effects were largely stable at 90 days as well. To our knowledge, this was the first educational intervention reporting intent to change practice patterns after completion.

Fifteen interventions geared toward practicing physicians took the form of online continuing education materials, which could be completed for CME credit. These were provided by 7 of the 12 investigated professional societies: AMA, ACP, the Endocrine Society, AAO-HNS, ASPS, ACOG, and AUA.

The AMA offers 5 CME activities, including 1 video and 4 articles. The video, “Ethics Talk: Providing Compassionate Care for Transmen,” introduces key ethical values involved with the care of transgender patients, and describes their ethical, clinical, legal, social, and cultural significance to practice patterns and policy-level issues. The 4 articles offered include 2 that are public health-focused: “Public Accommodation Laws and Gender Panic in Clinical Settings” and “Temporal Trends in Gender-Affirming Surgery Among Transgender Patients in the United States.”33,34 The other 2 focus on surgical aspects of transgender patient care: “Technical and Clinical Considerations for Facial Feminization Surgery With Rhinoplasty and Related Procedures,” and “What Surgeons Need to Know About Gender Confirmation Surgery When Providing Care for Transgender Individuals: A Review.”35,37

The ACP offers the Annals of Internal Medicine article, “Care of the Transgender Patient” for 1.5 CME credits.36 This article discusses terminology, components of an initial evaluation with transgender patients, medical management, transgender-specific surgeries, medicolegal and societal issues, and practice improvement.

The Endocrine Society’s “Endocrine Treatment of Gender Dysphoria/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline Educational Activity” is a series of 5 short modules for 1 CME credit, which aims to update physician knowledge of best practices with new evidence regarding hormonal treatment of transgender patients, and identify continued gaps in knowledge.12

The AAO-HNS provides 4 CME activities through their AcademyU service. “Cultural Competency in Your Otolaryngology Practice” teaches epidemiological statistics relevant to the transgender community as well as correct pronoun use.29 “The Transgender Voice: Treatment and Surgical Techniques” and “Caring for Transgender Patients: Focus on Voice Feminization” describe vocal feminization treatment options including vocal therapy and phonosurgery.28,30 “Transgender Patient Care in the Otolaryngology Practice” focuses on vocal feminization, facial feminization, and general care for transgender patients.31

The ASPS features “ASPS University: Gender Affirming Surgeries 101,” which is a video resource that teaches psychological evaluation requirements and hormonal management of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals prior to surgery; WPATH Standards of Care; the historical context of gender affirmation surgery; the embryology and anatomy involved in gender surgery; concepts of gender-affirming facial, genital, chest/breast, and body surgery; and health policy and patient safety risks that are unique to these procedures and this patient population.27 They also offer the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery article “Current Concepts in Feminizing Gender Surgery” as a 0.5 CME credit article that discusses appropriate treatment guidelines, including preoperative mental health and hormonal requirements; various surgical options for facial, chest, and genital feminization; key steps and anatomy during facial feminization, feminizing mammaplasty, and vaginoplasty; and major risks and complications of vaginoplasty.26

The ACOG’s “Improving Ob/Gyn Care for Transgender and Non-Binary Individuals” consists of 5 short online video modules, providing an overview of transgender terminology, preventive care for transgender patients, gender-affirming care, common gynecologic issues among transgender patients, and legal and insurance-related issues.10

The AUA’s “Genital Gender Affirming Surgery for Transgender Patients” is a 1-credit CME course that provides an overview of affirming transgender terminology, surgical options, postoperative management, and accepted care guidelines.11

Discussion

Here, the current state of transgender medical education was reviewed to produce a more comprehensive picture of these growing number of intervention types and modalities. The expansion of search criteria to include gray documents as well as publicly available medical education resources allows better identification of emerging trends and addresses some limitations of prior reviews. Identified trends include the increased representation of interdisciplinary, longitudinal, and post-residency educational interventions. However, a number of previously identified deficits in the literature remain.2

There is still no consensus regarding which formats or temporal placement of educational interventions are best suited to promote transgender health care learning. To the contrary, the continued emergence of multiple intervention modality types may suggest that while consensus on the importance of the topic may be emerging, the pedagogical approaches to teaching it remain varied. Several of these new formats are in line with increasingly prevalent calls for “all-clinician” education around transgender health topics, meant to ensure that not just newly graduated or highly motivated physicians achieve competence.43 The emergence of interdisciplinary interventions and online CME web modules from professional membership organizations signify the increasing priority of transgender health education for providers after training.

Interdisciplinary interventions hold the potential to encourage effective team communication and ensure that transgender patients are affirmed with every encounter, not just those with physicians. Ensuring that transgender patients feel affirmed and safe in health care environments depends to a large degree on the knowledge/attitudes/skills of nurses and advanced practice professionals, who in many situations have more consistent patient contact than physicians who may have been targeted in previous interventions.

Online courses, including CMEs, could be used to educate large cohorts of learners, encouraging “all-clinician” competency, especially for those without special interest in transgender health or access to concentrated cohorts of transgender patients.43 Continuing medical education courses also provide senior physicians, who would not directly benefit from interventions targeted toward trainees, with opportunities to improve on transgender health competencies. This may also have a “trickle down” effect to learners in the clinical learning environment.

The trend of longitudinal educational interventions regarding transgender health may provide key benefits as well. One advantage is spaced repetition to encourage memory integration and long-term learning. Presence of transgender health topics in a variety of educational settings may also help to “normalize” the topic and increase its perception as relevant to all providers.

Best practices for what format, when, and how often to optimally engage learners about transgender health cannot be determined given the absence of comparative studies. In addition, a larger base of evidence regarding the efficacy of various educational interventions in terms of how they translate to increased knowledge and culturally appropriate care for patients is needed. All of the interventions identified in our search demonstrated favorable outcomes regarding some or multiple domains of trainees’ knowledge, attitudes, and/or skills regarding transgender health care. However, despite this continued trend, there is too much variety among intervention modalities and learner audience type (ie, undergraduate, graduate, post-graduate) to define best practices. Rather, we believe the literature should be used on a case-by-case basis to determine intervention format feasibility and appropriateness for interested constituents until best practices have been determined.

We acknowledge that the modality of educational interventions chosen by each particular study is subject not just to its authors’ teaching philosophy but also to the curricular restraints to which the authors are subject. We also acknowledge that development of interventions similar to those discussed in this review will be subject to similar curricular constraints, and that even if the “ideal” format of a transgender health educational intervention could be ascertained, its implementation might not necessarily be feasible. For example, OSCE-type interventions are likely best for practicing clinical skills, but their implementation presents considerable logistic challenges.

A major shortcoming of the current literature is the lack of long-term follow-up data. The new studies added to this review were notable in that none addressed this previous shortcoming. One study by Braun et al16 demonstrated persistently improved knowledge, attitudes, and skills 90 days after a single educational intervention. However, only self-rated metrics were recorded, which do not necessarily reflect competency. Generally, the lack of follow-up data is concerning, as prior studies have demonstrated poor retention of educational content at 3-month follow-up.44 Future literature should seek to address these gaps, and it is important that they be added to this body of literature.

There were a number of recent trends in transgender health care that were not represented in our review. These include the increased emphasis on the health concerns of non-binary people, the effect of intersectional identities on transgender health, and the active engagement of the transgender community in endeavors influencing their own health. No educational interventions were identified that addressed either non-binary health specifically or intersectional identities. Only 1 study, by Cherabie et al, prominently featured transgender people as educators. Educational interventions would likely be enriched by attention to the gender diverse identities, intersectional identities, and lived transgender experience which are largely missing in the literature.

This review does not reflect the full breadth of educational interventions currently being implemented given the limitations of our search strategy. Many interventions remain unpublished, possibly due to time and resource constraints of the educationalists who innovate this type of curricular content. There are many interventions that are not captured in our search, in part because they are not captured in either published literature or medical education resources. We also did not examine the educational content on transgender health at in-person CME-providing conferences.

Conclusions

Medical education interventions around transgender health care are a recognized priority to alleviate health inequities faced by transgender individuals. The publication of educational interventions promoting knowledge, attitudes, and skills relevant to transgender health care continue to be published at an expanding rate. The variety of intervention types preclude identification of best practices for pedagogical interventions. Additional publications on this topic reveal a possible new trend toward post-training learner audiences. Limitations of current literature, including lack of objective outcomes data and especially long-term follow-up data, continue to be a major set-back in reaching consensus around key elements of pedagogical interventions for transgender medical education. However, the recent innovation and expansion in the types of educational offerings regarding the health of transgender and non-binary people will likely provide more answers and lead to best practices in the future.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: ITN, REG, and SDM designed the study; ITN, GB, SND, and LGG collected and analyzed the data; ITN, GB, SND, LGG, and SDM drafted the manuscript; all authors reviewed and provided critical feedback to the final manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Richard E Greene  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8618-7723

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8618-7723

Shane D Morrison  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3868-3532

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3868-3532

References

- 1. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG, Jr, Greene RE, Radix AE, Morrison SD. Transgender health care: improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:22-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greene MZ, France K, Kreider EF, et al. Comparing medical, dental, and nursing students’ preparedness to address lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer health. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sawning S, Steinbock S, Croley R, Combs R, Shaw A, Ganzel T. A first step in addressing medical education curriculum gaps in lesbian-, gay-, bisexual-, and transgender-related content: the University of Louisville Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Certificate Program. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2017;30:108-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol. 2015;70:832-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anton BS. Proceedings of the American Psychological Association for the legislative year 2008: minutes of the annual meeting of the Council of Representatives. Am Psychologist. 2009;64:372-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. American Medical Student Association. AMSA Constitution & Bylaws and Internal Affairs Preamble, Purposes and Principles; 2019. http://www.amsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2003-AMSA-PPP.pdf

- 9. Rafferty J. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Saghir A, Kalra AJ, de Haan G, et al. Training Modules: Improving Ob/Gyn Care for Transgender and Non-Binary Individuals. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Transgender Healthcare Curriculum; 2018. https://mmheadlines.org/2018/08/training-modules-improving-ob-gyn-care-for-transgender-and-non-binary-individuals/ [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garcia MM, Christopher NA, Ralpha DJ, Thomas P. Update Series (2017) Lesson 5: Genital Gender Affirming Surgery for Transgender Patients. Yerevan, Armenia: AUA University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Rosenthal SM, Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoria/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline Educational Activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2017;102:3869-3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Association of American Medical Colleges. Implementing Curricular and Institutional Climate Changes to Improve Health Care for Individuals Who Are LGBT, Gender Nonconforming, or Born with DSD. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Association of American Medical Colleges. Assessing Trainee Competence in LGBT Patient Care. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19-32. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braun HM, Ramirez D, Zahner GJ, Gillis-Buck EM, Sheriff H, Ferrone M. The LGBTQI health forum: an innovative interprofessional initiative to support curriculum reform. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1306419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Calzo JP, Melchiono M, Richmond TK, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent health: an interprofessional case discussion. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marshall A, Pickle S, Lawlis S. Transgender medicine curriculum: integration into an organ system-based preclinical program. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cherabie J, Nilsen K, Houssayni S. Transgender health medical education intervention and its effects on beliefs, attitudes, comfort, and knowledge. Kansas J Med. 2018;11:106-109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davidge-Pitts CJ, Nippoldt TB, Natt N. Endocrinology fellows’ perception of their confidence and skill level in providing transgender healthcare. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:1038-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vance SR, Jr, Lasofsky B, Ozer E, Buckelew SM. Teaching paediatric transgender care. Clin Teach. 2018;15:214-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Click IA, Mann AK, Buda M, et al. Transgender health education for medical students. Clin Teach. 2020;17:190-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Encandela J, Zelin NS, Solotke M, Schwartz ML. Principles and practices for developing an integrated medical school curricular sequence about sexual and gender minority health. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:319-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Park JA, Safer JD. Clinical exposure to transgender medicine improves students’ preparedness above levels seen with didactic teaching alone: a key addition to the Boston university model for teaching transgender healthcare. Transgender Health. 2018;3:10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oller D. Cancer screening for transgender patients: an online case-based module. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Safa B, Lin WC, Salim AM, Deschamps-Braly JC, Poh MM. Current concepts in masculinizing gender surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:857e-871e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deschamps-Braly J, Garcia M, Green J, et al. ASPS University: Gender Affirming Surgeries 101. Arlington Heights, IL: American Society of Plastic Surgeons; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mendelsohn A, Thomas JP, Vastine W. Caring for Transgender Patients: Focus on Voice Feminization: Part I and II (CME). Alexandria, VA: American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. El-Sayed A, Cabrera-Muffly C, Flanary VA, et al. Cultural Competency in Your Otolaryngology Practice. Alexandria, VA: American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mori M. The Transgender Voice: Treatment and Surgical Techniques (CME). Alexandria, VA: American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology-head and Neck Surgery; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chaiet SR, Perez K, Sturn AK. Transgender Patient Care in the Otolaryngology Practice (CME). Alexandria, VA: American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sallans R. Ethics Talk: Providing Compassionate Care for Transmen. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boskey E, Taghinia A, Ganor O. Public accommodation laws and gender panic in clinical settings. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20:E1067-E1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Canner JK, Harfouch O, Kodadek LM, et al. Temporal trends in gender-affirming surgery among transgender patients in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:609-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bellinga RJ, Capitan L, Simon D, Tenorio T. Technical and clinical considerations for facial feminization surgery with rhinoplasty and related procedures. JAMA Fac Plastic Surg. 2017;19:175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Care of the transgender patient. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:775-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Berli JU, Knudson G, Fraser L, et al. What surgeons need to know about gender confirmation surgery when providing care for transgender individuals: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:394-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Graham R, Blum R, Bockting W, et al. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lombardi E. Transgender health: a review and guidance for future research—proceedings from the Summer Institute at the Center for Research on Health and Sexual Orientation, University of Pittsburgh. Int J Transgend. 2010;12:211-229. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coker TR, Austin SB, Schuster MA. Health and healthcare for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: reducing disparities through research, education, and practice. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:213-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hart D. Toward better care for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients. Minn Med. 2013;96:42-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Khalili J, Leung LB, Diamant AL. Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-competent physicians. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1114-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ard KL, Keuroghlian AS. Training in sexual and gender minority health—expanding education to reach all clinicians. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2388-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kidd JD, Bockting W, Cabaniss DL, Blumenshine P. Special-“T” training: extended follow-up results from a residency-wide professionalism workshop on transgender health. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40:802-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]