Abstract

Background:

Fibromyalgia (FM) is characterized by chronic pain and fatigue, among other manifestations, thus advising interventions that do not aggravate these symptoms. The main purpose of this study is to analyse the effect of low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) on induced fatigue, pain, endurance and functional capacity, physical performance and cortical excitability when compared with a physical exercise program in women with FM.

Methods:

A total of 49 women with FM took part in this randomized controlled trial. They were randomly allocated to three groups: physical exercise group (PEG, n = 16), low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen therapy group (HBG, n = 17) and control group (CG, n = 16). Induced fatigue, perceived pain, pressure pain threshold, endurance and functional capacity, physical performance and cortical excitability were assessed. To analyse the effect of the interventions, two assessments, that is, pre and post intervention, were carried out. Analyses of the data were performed using two-way mixed multivariate analysis of variance.

Results:

The perceived pain and induced fatigue significantly improved only in the HBG (p < 0.05) as opposed to PEG and CG. Pressure pain threshold, endurance and functional capacity, and physical performance significantly improved for both interventions (p < 0.05). The cortical excitability (measured with the resting motor threshold) did not improve in any of the treatments (p > 0.05).

Conclusions:

Low-pressure HBOT and physical exercise improve pressure pain threshold, endurance and functional capacity, as well as physical performance. Induced fatigue and perceived pain at rest significantly improved only with low-pressure HBOT.

Trial registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03801109.

Keywords: cortical excitability, fibromyalgia, functional ability, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, pain, physical exercise

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a syndrome of unknown aetiology characterized by chronic, diffuse and generalized pain1 that directly affects the quality of life of those affected.2 Furthermore, FM patients have a decreased cardiorespiratory capacity compared with age-matched sedentary healthy subjects,3 vegetative disorders (mainly asthenia) and alteration of biological rhythms, which alter rest-activity circadian rhythms.4

These factors cause constant fatigue and insufficient muscle tissue repair, with increased pain, in individuals with FM.5 All this predisposes to disability and reduced physical functionality.6–8 In addition, previous studies have shown a decrease of motor cortex (M1) excitability in FM patients,9,10 which may be due to hypoexcitability of the corticospinal tract,10 and in turn, related to motor control dysfunction, causing inappropriate and fatiguing movement patterns.11

As a multisystem disorder with various concomitant symptoms, FM is approached from a multidisciplinary perspective. Pharmacological therapy is usually the main treatment,5 but given its chronicity, non-pharmacological approaches are needed to improve signs and symptoms. Some of the non-pharmacological therapies used include cognitive-behavioural therapy, such as patient education or relaxation techniques12 as well as nutrition education.13 However, the most commonly used non-pharmacological treatment is physical exercise, particularly low-intensity physical exercise,14 which has been shown to reduce perceived pain by improving the general physical condition, resulting in decreased fatigue and increased quality of life.15–17

However, prior investigations have shown poor-quality evidence on the reduction of pain intensity and improvement of physical function in FM.14 Further, the wide-spread pain experienced by people with FM usually hinders physical effort and, therefore, the adherence to this type of intervention may be jeopardized.18 Based on the foregoing, therapies need to be readdressed to include other pain and fatigue treatments not involving physical effort. In this regard, applying a therapy that focuses on improving tissue oxygenation, such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), may improve generalized fatigue,19 which could, in turn, reduce pain.

This therapy has been previously studied in other populations as an effective strategy to reduce fatigue which has been attributed to increased tissue oxygenation.20,21 Five studies that have evaluated the effects of HBOT in FM patients22–26 reported improved quality of life,22–24,26 reduced number of tender points and increased pressure pain threshold,23,26 as well as neuroplasticity induction and neuromuscular efficiency.23,25 However, high-pressure hyperbaric chambers were used in all these cases, between 2 and 2.5 atmospheres absolute (ATA), involving side effects, such as middle ear or sinus/paranasal barotrauma, or prodromal symptoms of central nervous system toxicity (the latter appearing in less than 50% of cases).27–29 For this reason, new protocols using lower pressure (e.g. 1.45 ATA) should be tested.

In addition, until now, the impact of HBOT has only been compared against a placebo treatment26 or with groups that have not performed any type of treatment,23,24 but no study has compared this type of intervention with physical exercise, which, as discussed, is the most commonly used treatment.

The main purpose of this study is to analyse the effect of low-pressure HBOT on induced fatigue, pain and endurance, and functional capacity when compared with those obtained from a physical exercise program in women with FM. Further, we aim to explore the impact of such therapy on physical performance and cortical excitability.

Methods

Participants

A total of 49 women diagnosed with FM participated in this study. They were recruited from several fibromyalgia associations over a 4-month period (September 2017 to January 2018). The inclusion criteria were: women aged 30–70 years and diagnosed by a rheumatologist according to the 2016 American College of Rheumatology [i.e. they should meet the following criteria: generalized pain for at least 3 months and a widespread pain index (WPI) ⩾7 and symptom severity scale (SSS) ⩾ 5 or a WPI of 4–6 and a SSS score ⩾ 9].30 Further, they should have followed pharmacological treatment for more than 3 months without clinical improvements and have the capacity to sign the informed consent form accordingly.

Exclusion criteria were: pregnancy or breastfeeding; presence of other advanced-stage pathologies associated with the locomotor system that make physical activity impossible (arthritis, osteoarthritis, uric acid); tympanic perforations; epilepsy; drugs that lower the convulsive threshold; history of intense headaches; endocranial and hearing implants; non-fibromyalgia-related pathology affecting the nervous system, either central or peripheral; endocranial hypertension; uncontrolled arterial hypertension; heart and/or respiratory failure; cardiac pacemaker; pneumothorax; claustrophobia and/or psychiatric pathologies; neoplasia and surgical interventions in the last 4 months. Further, patients with addiction problems related to alcohol, psychoactive drugs or narcotics were excluded. Moreover, patients should never have received previous treatment with a hyperbaric chamber, and they should not have been enrolled in any physical exercise program 2 months before the study began. All these issues were evaluated with a careful anamnesis and the information was further supervised by medical specialists when necessary. Participants who failed to accomplish the inclusion criteria or met any exclusion criteria was excluded from the study.

Study design

A randomized controlled trial was carried out (within a broader project [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03801109]). The participants were randomly allocated to three different groups using simple randomization with Random Allocation Software31 by an external assistant who was blinded to the study objectives: physical exercise group (PEG) (n = 16), hyperbaric oxygen therapy group (HBG) (n = 17) and control group (CG) (n = 16). To analyse the effect of the interventions, two assessments were carried out: one at baseline, before treatment (T0) and another upon completion (T1). To reduce bias, both the physical therapist who performed the assessments and the statistician were unaware of group allocation.

All participants provided written informed consent, while all procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and the protocols were approved independently by the Ethics Committee of the Universitat de València (H1548771544856).

Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated taking into consideration the three study groups measured twice and expecting a medium effect size (d = 0.5). Further, a type I error of 5% and a type II error of 20% were set. The result of this calculation amounted to 42 volunteers (14 in each group). Ultimately, 49 women were included to prevent loss of power due to possible dropouts. G-Power® version 3.1., was used for sample size estimation (Institute for Experimental Psychology, University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany).

Intervention procedures

As reported, the participants were allocated to three different interventions as further discussed below. The treatments were applied by two physiotherapists with more than 4 years’ experience in these techniques. Participants were not receiving any other rehabilitation or pain treatment intervention as part of the study protocol.

Low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen treatment

The participants of this group received low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen treatment, consisting of a total of 40, 90-minute sessions, with five sessions per week. For the prevention of anxiety and irritability,32 100% oxygen with air breaks at 1.45 ATA, was used. Oxygen purity at 97% was applied with a mask to the participants inside the hyperbaric chamber. In addition, an anti-panic button was available. The hyperbaric chamber used was Revitalair® 430 (Biobarica, Buenos Aires, Argentina). Every day participants recorded their level of pain according to visual analogue scale (VAS) before and after each session. The session ended if patients reported intense headache or earache or severe muscle soreness (i.e. ⩾7.5 on VAS).33

Low-intensity physical exercise

Participants of this group were enrolled in a low-intensity physical exercise program using the following protocol: 16 sessions in all, two sessions a week, 60 min each. Exercises were divided into three parts: a 10-minute warm-up, 40 min training and 10 min cool-down. Training included following a combined endurance and coordination protocol based on a previous study from our group.16 The objectives of physical exercise were: to reduce fatigue, reduce pain, improve endurance and aerobic capacity for which the volume and intensity of work was defined and controlling heart rate (HR) based on the exertion perceived and the number of repetitions.

In order to achieve the objectives, 16 progressive sessions were designed, the first four sessions being devoted to adjusting participants to the exercise in a progressive way. This first phase included walking for 15 min at a comfortable speed, and completion of a set of 10 exercises for 25 min, performing 10 repetitions of each one.

In the first session, as a familiarization phase, participants started by using 1-kg dumbbells and ballast weights to conduct the exercises at a velocity determined by a metronome set at 60 beats per minute. With this load and velocity, participants performed all the exercises and the perceived exertion was subsequently registered. To ensure that the perceived effort was weak or very weak (i.e. 1–2 categories in the Borg CR-10),34 the load was adjusted for the next two sessions. In the fourth session, the load was again modified to ensure a moderate effort (i.e. 3–4 categories in the Borg CR-10) for the rest of the sessions.

In the second phase (5th–16th session) the exercise circuit was performed for 40 min. For each exercise, participants had to perform as many repetitions as possible in 1 min. The number of repetitions and load varied depending on the participant, as they were allowed to adapt the exercise according to their pain and perceived exertion each day; however, repetitions were always in the range of 15–25, which meets the health recommendations of physical exercise according to the 2014 Guide for the prescription of physical exercise of American College of Sport Medicine for endurance training.35

The exercises for combined training were designed to target endurance and coordination. Endurance training focused on the strengthening of upper and lower limbs using dumbbells/weights with a load of 0.5–2 kg for the upper limbs and 1–3 kg for the lower limbs. Soft elastic bands were also used for limb and trunk training, which involve a resistance of 13 N when the band is stretched to double its length (100% deformation).36 Coordination and flexibility exercises included flexing heels up and down, sitting down and getting up from a chair, stepping up and down and throwing a ball into the air and catching it. In this intervention, participants also recorded their level of pain according to VAS before and after each session. The session ended if patients reported severe pain (i.e. ⩾7.5 on VAS).33

Control group

Participants assigned to this group received no kind of therapy and were asked to perform their usual routines, that is, to continue with their usual medication, without increasing or lowering the dose (as in all other groups) and if they did any physical activity, they should also continue with this without increasing or reducing it. The time from the first evaluation to the re-evaluation was also 8 weeks, equivalent to the period used in PEG and HBG. Upon study conclusion, the participants of this group were offered to choose one of the previous treatments (according to their preference).

Assessments

All assessments were conducted twice, once before the intervention and another after the intervention (in the following week).

Induced fatigue

Fatigue following the completion of the 6-minute walking test (6MWT) test was measured using the CR-10 Borg scale, which has been shown to be valid and reliable in women with FM.37 Participants should specify their sensation of fatigue after walking for 6 min.38

Pain

The intensity of perceived pain at rest was measured using a 100-mm VAS, whose reliability and validity has been previously reported for chronic pain.39 The VAS consisted of a continuous line between two endpoints, with 0 being no pain and 100 being maximum tolerable pain.

Pressure pain threshold

We assessed the pressure pain threshold (PPT) in each of the 18 tender points formerly used to diagnose FM. We used an algometer (WAGNER Force Dial TM FDK 20/FDN 100 Series Push Pull Force Gage, Greenwich CT, USA) to assess the PPT (i.e. the smallest stimulus causing the sensation of pain) of the soft tissues located bilaterally at occiput, lower cervical muscles, trapezius, supraspinatus, second ribs, lateral epicondyle, gluteal muscles, greater trochanter and knees. The presence and location of the tender points was first confirmed via palpation and was pen-marked by an experienced physiotherapist. The pressure threshold was then measured by applying the algometer directly to the tender point, with the axis of the shaft at 90° relative to the explored surface. The algometer tip was 1 cm2 and the pressure values were reported in kg/cm2. The subject was instructed to verbally report any feeling of pain or discomfort as soon as this started. The procedure used has excellent intra-observer reliability.40

Since in the preliminary exploratory analyses of data (repeated measures t-Test) no differences between hemibodies were found, the average pressure pain threshold of the two sides was provided for subsequent analyses.

Endurance and functional capacity

The 6MWT was used to assess walking endurance and functional capacity. Participants walked 15 meters along a hallway for a total of 6 min.41 Before starting, patients sat in a chair located near the starting line. Any previous contraindications were checked before the test started, thus recording HR, oxygen level and Borg rate of perceived fatigue in addition to the main variable, namely, the walked distance.

Patients were allowed to take as many standing rests as they liked, but the timer kept going. The instructions given to the patients were: ‘Walk to the turnaround point at each end. I am going to use this counter to keep track of the laps you complete. You may stand and rest, but resume walking as soon as you are able. Remember the aim is to walk as far as possible, but do not run or jog’. The test-retest reliability has been proved as excellent.42

Physical performance

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) was carried out to assess physical performance. The SPPB consists of three subtests: a hierarchical test of balance, a short walk at usual pace and standing up from a chair five times consecutively. Performance of the balance test required holding 3 positions: feet together, semi-tandem and tandem for 10 s each. For the walking test, the participant walked a distance of 4 meters at their usual pace. Finally, in the getting-up and sitting-down in a chair test, the participant would stand and sit 5 times, as quickly as possible, and the total time used was recorded. Each test scores from 0 (worst performance) to 4 (best performance). In addition, a total score is obtained for the entire set, which is the sum of the three tests and ranges from 0 to 12.43

Cortical excitability

Brain excitability was measured by recording the resting motor threshold (RMT), by surface electromyography using Neuro-MEP-Micro integrated in a Neuro-MS/D transcranial magnetic stimulator (Neurosoft®, Ivanovo, Russia). The RMT is defined as the minimum signal strength that must be provided for an evoked motor potential of at least 50 microvolts in 50% of the tests.9,44 To determine the RMT, TMS_MTAT_2.0.1 software was used, which based on an algorithm allowed to set the number of repetitions needed and to select those where at least 50 mV were obtained, in the first dorsal interosseous of the right hand. To obtain this, a single-pulse left hemisphere stimulation was performed using the Neuro-MS/D magnetic stimulator with a figure-of-eight-shaped coil. The coil was placed at the motor cortex M1, at a 45° angle with respect to the midline.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v.24 (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Standard statistical methods were used to obtain the mean and standard deviation (SD). Inferential analyses of the data were performed using two-way mixed multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), with an inter-subject factor called ‘group’ with three categories (PEG, HBG and CG) and a within-subject factor called ‘treatment’ with two categories (T0 and T1). Post hoc analysis was conducted using the Bonferroni correction provided by the statistics package used, and the effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d. We also compared the age and the level of pain experienced between groups using a one-way MANOVA to ensure that the groups were similar at baseline. Type I error was established as <5% (p < 0.05).

Results

Participants

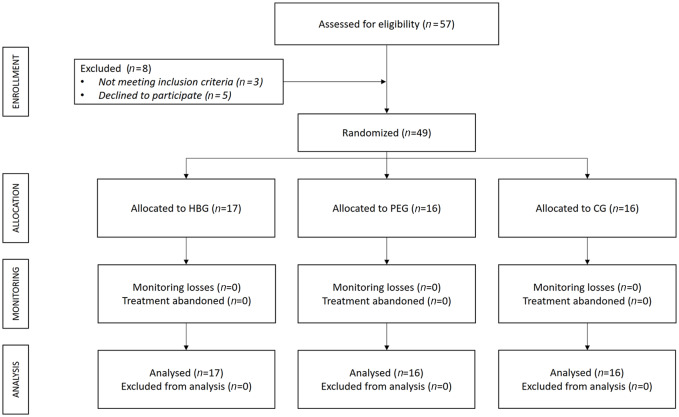

A total of 57 women were assessed for eligibility, three failed to meet inclusion criteria and five declined to participate; accordingly, 49 participants were randomized and all of them completed the study (17 in HBG, 16 in PEG and 16 in CG) (Figure 1). The mean (SD) age for the participants was 53.30 (7.86) years, weight, 68.48 (14.34) kg and height, 1.61 (0.06) m. There were no statistically significant differences in age, weight or height between the three groups (p > 0.05; data not shown). No incidents were reported during the interventions.

Figure 1.

Flowchart according to CONSORT Statement for the Report of randomized trials.

CG, control group; HBG, hyperbaric Group; PEG, physical exercise group.

Effects of the interventions

A significant multivariate effect of the interaction between “group” and “treatment” was obtained [F(32,64) = 2.29, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.53]. The significant differences and effect size among the pre- and post-treatment assessments (i.e. T0 and T1) for each group and each variable are shown in the following tables, as well as the differences between groups in each of the assessments.

The perceived pain, recorded by a VAS, significantly improved approximately 2.5 points in the HBG only, as opposed to what occurred in the PEG and CG (as noted in Table 1). However, results from the PPT assessment revealed that a significant improvement was achieved in the HBG only for the lateral epicondyle and gluteal points, while PEG achieved significant improvements in occiput, lower cervical area, second ribs, great trochanters and knees. CG failed to achieve a significant improvement in any of the pain-related variables (p > 0.05). By contrast, the PPT assessment revealed a significant decrease of pain threshold in occiput, trapezius and supraspinatus.

Table 1.

Effect of the interventions on pain and pressure pain threshold.

| PEG |

HBG |

CG |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Effect size (d) | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Effect size (d) | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Effect size (d) | |

| VAS (cm) | 6.13 (2.22) | 5.38 (2.16) | 7.35 (1.66) | 4.88 (2.32) | 1.06 | 5.63 (1.75) | 5.5 (2.25) | ||

| Occiput (kg.cm –2 ) | 1.75 (0.94) | 2.18 (1.05) | –0.64 | 1.56 (0.74) | 1.66 (0.69) | 1.82 (0.38) | 1.37 (0.45) | 0.68 | |

| Lower Cervical muscles (kg.cm –2 ) | 1.05 (0.89) | 1.63 (0.91) | –0.98 | 1.20 (0.63) | 1.27 (0.64) | 1.36 (0.42) | 1.12 (0.55) | ||

| Trapezius (kg.cm –2 ) | 1.82 (0.95) | 1.92 (0.68) | 1.70 (0.63) | 1.86 (0.75) | 1.89 (0.71) | 1.55 (0.97) | 0.56 | ||

| Supraspinatus (kg.cm –2 ) | 2.29 (1.24) | 2.6 (1.45) | 1.89 (0.60) | 2.13 (0.78) | 2.21 (0.93) | 1.74 (0.70) | 0.57 | ||

| Second ribs (kg.cm –2 ) | 1.38 (1.11) | 1.79 (0.91) | –0.84 | 1.61 (0.56) | 1.8 (0.58) | 1.55 (0.41) | 1.33 (0.67) | ||

| Lateral epicondyle (kg.cm –2 ) | 1.35 (0.74) | 1.57 (0.55) | 1.38 (0.33) | 1.75 (0.48) | −0.69 | 1.48 (0.33) | 1.24 (0.48) | ||

| Gluteal muscles (kg.cm –2 ) | 2.55 (2.18) | 2.72 (2.14) | 1.85 (0.84) | 2.28 (0.76) | –0.61 | 2.00 (0.53) | 1.68 (0.73) | ||

| Greater trochanters (kg.cm –2 ) | 2.09 (1.25) | 2.51 (1.50) | –0.57 | 1.84 (0.44) | 2.12 (0.81) | 1.91 (0.80) | 1.88 (0.76) | ||

| Knees (kg.cm –2 ) | 1.43 (0.81) | 1.97 (1.03) | –0.72 | 1.74 (0.64) | 2.02 (0.85) | 1.62 (0.62) | 1.44 (0.76) | ||

Data are expressed as mean (SD).

CG, control group; d, Cohen’s d effect size reported only when the differences were significant; HBG, Hyperbaric therapy group; PEG, Physical exercise group.

Bold type means statistically significant differences between pre- and post-treatment measurements (p < 0.05).

Regarding the variables related to endurance and functional capacity, our results (Table 2) showed that a significant improvement of induced fatigue was achieved only in the HBG. Oxygen saturation and HR were not significantly influenced by any of the treatments received. Further, the distance achieved significantly improved with both low-pressure HBOT and physical exercise programs, although the size effect of the hyperbaric treatment was larger. The resting motor threshold slightly decreased in the PEG but achieved no significant threshold (the p value was 0.054). CG failed to achieve any significant improvement (p > 0.05) in any of the endurance or functional capacity variables. In fact, HR was significantly poorer in this group.

Table 2.

Effect of interventions on endurance and functional capacity and resting motor threshold.

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Effect size (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Fatigue | PEG | 6.81 (2.64) | 7.00 (2.48) | ||

| HBG | 7.94 (1.78) | 6.76 (2.14) | 0.53 | ||

| CG | 6.84 (2.05) | 6.75 (2.62) | |||

| 6-minute walking test | Oxygen saturation | PEG | 97.25 (0.93) | 97.75 (1.18) | |

| HBG | 98.29 (0.92) | 98.06 (0.83) | |||

| CG | 97.63 (1.36) | 97.69 (1.08) | |||

| Heart rate | PEG | 111.38 (21.01) | 113.56 (23.37) | ||

| HBG | 109.00 (17.64) | 113.12 (19.7) | |||

| CG | 115.44 (15.14) | 127.75 (20.65) | –0.61 | ||

| Distance | PEG | 481.00 (71.23) | 513.00 (64.84) | –0.75 | |

| HBG | 508.76 (62.71) | 558.29 (68.83) | –1.16 | ||

| CG | 493.19 (68.48) | 497.31 (76.29) | |||

| RMT | PEG | 42.56 (9.38) | 40.31 (5.68) | 0.50 (p = 0.054) | |

| HBG | 39.76 (7.67) | 38.35 (6.04) | |||

| CG | 45.25 (8.42) | 45.19 (7.87) |

Data are expressed as mean (SD).

CG, control group; d, Cohen’s d effect size reported only when the differences were significant; HBG, hyperbaric therapy group; PEG, physical exercise group; RMT, resting motor threshold.

Bold type means statistically significant differences between pre- and post-treatment measurements (p < 0.05).

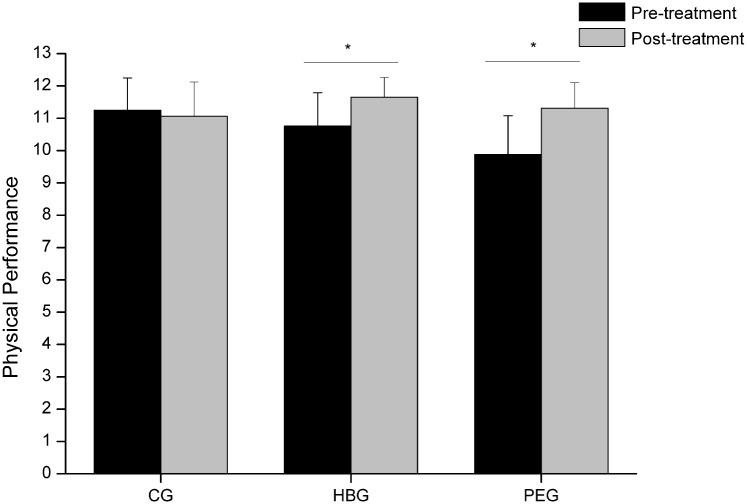

Finally, the SPPB score, related to physical performance, increased significantly in both treatments while remaining unchanged for CG (Figure 2). The difference in PEG was substantial mean (SE) of 1.4 (0.23) points, while moderate in HBG, specifically 0.89 (0.23) points in accordance with the classification of the differences reported by Perera et al.45

Figure 2.

Physical performance score in the studied groups before and after the interventions.

Bars represent the mean and error bars, the standard deviation.

CG, control group; HBG, hyperbaric therapy group; PEG, physical exercise group.

Discussion

Our study has investigated the impact of low-pressure HBOT on induced fatigue, pain, endurance, functional capacity, physical performance and cortical excitability and compared the achieved results with those obtained following a low-intensity physical exercise protocol and with a control group. Low-pressure HBOT is shown to significantly reduce induced fatigue and to achieve significant improvements in perceived pain at rest and pressure pain threshold, although only in the lateral epicondyle and gluteal areas. Further, this therapy improved the endurance and functional capacity, and physical performance. On the contrary, the physical exercise program did not improve the perceived pain or induced fatigue, although significant improvements were obtained in the pressure pain thresholds of some of the tender points (i.e. occiput, low-cervical, second ribs, greater trochanters and knees) and this approach also improved the endurance and functional capacity and physical performance in a similar way, as did the low-pressure HBOT intervention.

Low-pressure HBOT significantly improved the feeling of fatigue after the completion of the 6MWT test (by 1.18 points). This may be due to an increased oxygen supply to the musculoskeletal system, which activates cellular activity (i.e. increases adenosine triphosphate synthesis) and promotes the metabolism of fatigue-related substances.46 Specifically, fatigue-associated metabolic factors produced during the process of contraction are hydrogen ions, lactate, inorganic phosphate, reactive oxygen species, heat shock protein and orosomucoid (reviewed in Wan et al.47), which may be better removed after applying an oxygen therapy. Indeed, it has been reported that HBOT reduces fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome,20 which has been attributed to its ability to lower reactive oxygen species and acid lactic levels, and in muscle fatigue after exercise.21 However, this decreased fatigue was not found in PEG. These negative results are in line with those achieved in the study conducted by Giannotti et al. and Fontaine et al. who similarly failed to obtain significant improvements in the fatigue felt following the exercise intervention.48,49 These findings support the effectiveness of HBOT, and not low-intensity physical exercise, to address fatigue in women with FM.

In addition, low pressure HBOT has achieved a significant decrease of 2.47 points in perceived pain. This could be due to the action of oxygen, which stimulates the growth of blood vessels and promotes tissue recovery, thus decreasing tissue hypoxia that causes pain.50–53 It may also cause a change in the brain pain-processing activity, due to changes in blood flow in the posterior and prefrontal regions of the brain.23 In addition, HBOT stimulates nitric oxide synthesis, which helps to alleviate hyperalgesia and NO-dependent release of endogenous opioids which has been proposed to be the primary HBOT mechanism of antinociception.54 This decrease in pain is in line with Yildiz’s study,26 which used a similar treatment protocol, although with greater pressure than that applied in our study and which obtained significant improvements for pain scores in as much as 3.31 points. This confirms that, although the pressure applied in our study is lower than that used to date, which could avoid the aforementioned complications, it is sufficient to significantly reduce pain, with a result that exceeds 1 cm considered the minimum clinically relevant change.55,56 However, the physical exercise program failed to improve the perceived pain (mean difference of 0.75 cm). The fact that no significant improvements have been found in the scores obtained in the VAS, as opposed to other studies,16,48,57,58 may be due to poor physical exercise habits in these subjects, failing to adjust to the pace of the proposed physical exercise, which could cause excessive effort and thus a continued feeling of pain. However, the results of the pressure pain threshold at specific tender points showed a significantly greater impact of physical exercise compared with those obtained with hyperbaric treatment. While the perception of generalized pain takes into account the resulting pain, regardless of the trigger factor, when assessing the pain threshold at these tender points, the painful reaction to a mechanical stimulus, such as pressure, is specifically assessed. This response is influenced by muscle condition, which may have improved to a greater extent with the physical exercise program, as revealed by the size effect of the physical performance improvement, this being greater than that achieved with low-pressure HBOT, as discussed below. Low-pressure HBOT has improved the pain threshold at only two of the tender points, namely, the lateral epicondyle and the gluteal muscle, increasing the value by 0.37 and 0.43 kg/cm2, respectively. Nevertheless, the values obtained, although above the standard error of measurement, do not achieve the minimal detectable change (i.e. 0.54 kg/cm2)59 Studies by Efrati et al.23 Yildiz et al.26 reported that HBOT improved the pressure pain threshold, inducing an increase of between 1.07–1.14 kg/cm2 and 0.62 kg/cm2 respectively, although in both cases greater pressure was used. On the other hand, participants who followed a physical exercise program obtained significant improvements in the tender points of the occipital area, lower neck, second intercostal space, major trochanter and knees. These results are consistent with previous studies that have shown a beneficial effect of physical exercise on the pain threshold.60–62 As discussed above, improved muscle condition may help to improve the pain threshold under mechanical stimulation.63–65 In fact, poor fitness in women with FM is related to increased sensitivity to pain.66

Improvements were also obtained in endurance and functional capacity measured with the 6MWT test, where the HBG increased for the distance covered, with an average of 49.53 meters which exceeded the minimal clinically important difference, ranging from 14 to 35 m according to the review by Bohannon et al.67 These improvements could be due to enhanced tissue oxygenation produced by HBOT, which would accelerate the recovery of exercise-induced muscle damage.50 Indeed, O2 plays an essential role in cell metabolism and its availability is a main determinant of maximal O2 uptake68 which can be predicted by the 6MWT.69,70 Similarly to HBG, PEG improved in endurance and functional capacity, increasing the distance covered by 32 meters. These improvements are due to the fact that PEG training directly affected the physical capacity of each participant, as it mainly consisted of aerobic training, combined with soft load and coordination exercises. These results are consistent with those reported by several authors showing improvements in endurance and functional capacity after physical exercise training in people with fibromyalgia.48,57,58,71 Following the 6MWT test, no significant changes were observed in either HR or O2 saturation in either of the two experimental groups. By contrast, the CG revealed a significant HR increase of 12.31 pulsations after 8 weeks, which might be associated with the aggravated symptomatology in this group. In this regard, it has been proposed that there is a relationship between symptomatology and cardiorespiratory capacity,3 whereby the greater the symptomatology, the poorer the cardiorespiratory capacity.

Although SPPB was first designed for the elderly, it provides an appropriate level of challenge for many adults with chronic pain.72 For this reason, it has been used to evaluate physical performance, thus being able to objectify improvements for both HBG and PEG. Participants who underwent hyperbaric chamber treatment managed to significantly increase (0.89 points) the total score for this test, which implies an improvement in physical condition. This improvement may again be due to increased tissue perfusion,53 especially in muscles, which would lead to increased tissue regeneration,51,52 increased oxygenation of damaged muscle structures and decreased swelling.50 This could lead to reduced pain and fatigue, which in turn could lead to better physical performance. No previous study using HBOT has evaluated physical performance, so the effects achieved in our study should not be compared with previous studies. With respect to women in PEG, they obtained an even greater improvement than those in HBG, according to the classification proposed by Perera, et al.45 PEG scores increased to 1.43 compared with 0.89 points in HBG, which could be due to the training program addressed in this study. A combined endurance and coordination protocol using work stations which consisted of 1 min exercise and 1 min rest, implying increased cardiac output, with changes in the pace and therefore constant cardiac training could generate adjustment to exertion73 and therefore present enhanced physical performance after the intervention.

Finally, cortical excitability has not improved with low pressure HBOT. This may be because low pressure HBOT does not directly affect M1, also known as Brodmann area 4, since, as explained by Efratti et al., the areas with most activity in the frontal lobe after HBOT measured by single photon emission computed tomography are: 25, 10, 47, 45, 11, 9, 8 and 38.23 The PEG likewise failed to achieve a significant improvement, although there was a trend (p = 0.054). As previously described, RMT in fibromyalgia patients is high. It has been proposed that this is due to the fact that the cortical excitability is altered and greater intensity is needed to achieve movement, which could be related to several underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of fibromyalgia9 including internal cortical dysfunction in the motor cortex,10 as well as poor patterns of movement or of cortical motor control.11 Slight, but not significant improvement in PEG may be due to the fact that it is the only treatment that directly affects movement control and may therefore influence the motor cortex after physical training as reported by other studies.74,75 In fact, McDonnell’s group concluded that only low-intensity exercise can effect changes in the motor cortex as in our study,76 which could explain the absence of significant results in other studies that used high-intensity aerobic exercise.77,78 Further studies with a larger sample size are needed to ensure that the absence of significant differences are not due to a type II error.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental study comparing a treatment that requires physical exertion (i.e. physical exercise) against passive treatment (i.e. low pressure HBOT). Both treatments have been shown to be effective in terms of pain threshold, endurance, functional capacity and physical performance, with further improvements in HBG in the feeling of fatigue and perceived pain. By contrast, CG showed no improvements in any of the variables studied (p > 0.05), and the PPT even dropped at three of the analysed tender points (i.e. occipital area, trapezius and supraspinatus) in addition to an increase in HR. Therefore, either treatment could be appropriate to improve the health condition in this population as symptomatology improved. However, given that the physical exercise does not decrease the subjective pain or the feeling of fatigue, unlike what happens with low pressure HBOT, this might lead to lower adherence to the physical exercise intervention.

Limitations

The main limitation of the current study is the small sample size. Although our sample size calculation showed that our selected sample size was even larger than that required to obtain significant results, future studies should corroborate these findings with a larger sample size. Another limitation is that a follow-up measurement was not provided, which would have been of great interest to assess the durability of the treatment effects in chronic cases (i.e. the FM syndrome). Lastly, since FM syndrome mostly affects women, we included only women, and thus the gender effect has not been studied.

Conclusion

The results suggest that both low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen therapy and an 8-week program of low-impact physical exercise improve pain pressure threshold in some muscles at rest, endurance and functional capacity measured as the amount of distance walked, as well as physical performance in daily life activities. Induced fatigue and perceived pain at rest significantly improved only with low-pressure hyperbaric treatment. Thus, low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen treatment may be the treatment of choice in women with FM reporting high levels of pain and fatigue.

Acknowledgments

We thank the AVAFI association and all the participants taking part in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Ruth Izquierdo-Alventosa  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2752-6999

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2752-6999

Pilar Serra-Añó  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0743-3445

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0743-3445

Contributor Information

Ruth Izquierdo-Alventosa, UBIC research group, Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Physiotherapy, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain; FIVAN Foundation, Valencia, Spain.

Marta Inglés, Freshage Research Group, Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Physiotherapy, University of Valencia, CIBERFES-ISCIII, INCLIVA, Valencia, Spain.

Sara Cortés-Amador, UBIC research group, Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Physiotherapy, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain.

Lucia Gimeno-Mallench, Freshage Research Group, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Valencia, CIBERFES-ISCIII, INCLIVA, Valencia, Spain.

Núria Sempere-Rubio, UBIC research group, Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Physiotherapy, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain.

Javier Chirivella, FIVAN Foundation, Valencia, Spain.

Pilar Serra-Añó, Department of Physiotherapy, UBIC research group, Faculty of Physiotherapy, University of Valencia, Gascó Oliag Street, 5, Valencia, 46010, Spain.

References

- 1. Vierck CJ. Mechanisms underlying development of spatially distributed chronic pain (fibromyalgia). Pain 2006; 124: 242–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sempere-Rubio N, Aguilar-Rodríguez M, Inglés M, et al. Physical condition factors that predict a better quality of life in women with Fibromyalgia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corrales BS, Orea DG. Relación entre capacidad cardiorrespiratoria y fibromialgia en mujeres. Reumatol Clin 2008; 4: 8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Revuelta Evrard E, Segura Escobar E, Paulino Tevar J. Depression, anxiety and fibromyalgia. Rev la Soc Esp del Dolor 2010; 17: 326–332. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chaves HD. Revisión Bibliogárica. Actualización en fibromialgia. Med Leg Costa Rica 2013; 30: 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Carbonell-Baeza A, Segura-Jiménez V, et al. Physical fitness reference standards in fibromyalgia: the al-Ándalus project. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016; 27: 1477–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA, Sjöström M, et al. Pain and functional capacity in female fibromyalgia patients. Pain Med 2011; 12: 1667–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dailey DL, Frey Law LA, Vance CGT, et al. Perceived function and physical performance are associated with pain and fatigue in women with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther 2016; 18: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mhalla A, de Andrade DC, Baudic S, et al. Alteration of cortical excitability in patients with fibromyalgia. Pain 2010; 149: 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salerno A, Thomas E, Olive P, et al. Motor cortical dysfunction disclosed by single and double magnetic stimulation in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Neurophysiol 2000; 111: 994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pierrynowski MR, Tiidus PM, Galea V. Women with fibromyalgia walk with an altered muscle synergy. Gait Posture 2005; 22: 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fernández BR, Campayo JG, Casanueva B, et al. Tratamientos no farmacológicos en fibromialgia : una revisión actual. Rev Psicopatología y Psicol Clínica 2009; 14: 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Silva AR, Bernardo A, Costa J, et al. Dietary interventions in fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Ann Med 2019; 51(Suppl. 1): 2–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, et al. Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 6: CD012700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ambrose KR, Golightly YM. Physical exercise as non-pharmacological treatment of chronic pain: why and when. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015; 29: 120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Espí-lópez GV, Inglés M, Ruescas-Nicolau MA, et al. Effect of low-impact aerobic exercise combined with music therapy on patients with fibromyalgia. A pilot study. Complement Ther Med 2016; 28: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Serra-Añó P, Pellicer-Chenoll M, García-Massó X, et al. Effects of resistance training on strength, pain and shoulder functionality in paraplegics. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 827–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Del Rosso A, Maddali-Bongi S. Mind body therapies in rehabilitation of patients with rheumatic diseases. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2016; 22: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilson HD, Wilson JR, Fuchs PN. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment decreases inflammation and mechanical hypersensitivity in an animal model of inflammatory pain. Brain Res 2006; 1098: 126–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akarsu S, Tekin L, Ay H, et al. The efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the management of chronic fatigue syndrome. Undersea Hyperb Med 2013; 40: 197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shimoda M, Enomoto M, Horie M, et al. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on muscle fatigue after manual intermitent plantar flexion exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2015; 29: 1648–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Atzeni F, Casale R, Alciati A, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment of fibromyalgia: a prospective observational clinical study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019; 37(Suppl. 116): 63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Efrati S, Golan H, Bechor Y, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy can diminish fibromyalgia syndrome – prospective clinical trial. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0127012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. García EA, Delgado MJC, Mukodsi CM, et al. Eficacia del tratamiento con cámara hiperbárica en pacientes con diagnóstico de fibromialgia. Rev Cuba Reumatol 2012; 16: 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Casale R, Boccia G, Symeonidou Z, et al. Neuromuscular efficiency in fibromyalgia is improved by hyperbaric oxygen therapy: looking inside muscles by means of surface electromyography. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019; 37(Suppl. 116): 75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yildiz Ş, Kiralp MZ, Akin A, et al. A new treatment modality for fibromyalgia syndrome: hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Int Med Res 2004; 32: 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mortensen CR. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Curr Anaesth Crit Care 2008; 19: 333–337. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shirley PJ, Ross JAS. Hyperbaric medicine part I: theory and practice. Curr Anaesth Crit Care 2001; 12: 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heyboer M, III, Sharma D, Santiago W, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: side effects defined and quantified. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2017; 6: 210–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. 2016 revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016; 46: 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saghaei M. Random allocation software for parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2004; 4: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jokinen-Gordon H, Barry RC, Watson B, et al. A retrospective analysis of adverse events in hyperbaric oxygen therapy (2012-2015): lessons learned from 1.5 million treatments. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017; 30: 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boonstra AM, Preuper HRS, Balk GA, et al. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the visual analogue scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain 2014; 155: 2545–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borg G. Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales, 1st ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1998, p.120. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pescatello L. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 9th ed. In: Pescatello LS, Arena R, Riebe D, Thompson PD. (eds) The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, Vol. 58 Baltimore, PA: ASCM Group Publisher: Kerry O’Rourke, 2014, p.328. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simoneau GG, Bereda SM, Sobush DC, et al. Biomechanics of elastic resistance in therapeutic exercise programs. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2001; 31: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Soriano-Maldonado A, Ruiz JR, Álvarez-Gallardo IC, et al. Validity and reliability of rating perceived exertion in women with fibromyalgia: exertion-pain discrimination. J Sports Sci 2015; 33: 1515–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gibbons WJ, Fruchter N, Sloan S, et al. Reference values for a multiple repetition 6-minute walk test in healthy adults older than 20 years. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2001; 21: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain 1983; 16: 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Farasyn A, Meeusen R. Pressure pain thresholds in healthy subjects: influence of physical activity, history of lower back pain factors and the use of endermology as a placebo-like treatment. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2003; 7: 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 41. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166: 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pankoff BA, Overend TJ, Lucy SD, et al. Reliability of the six-minute walk test in people with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res 2000; 13: 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994; 49: M85–M94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hashemirad F, Zoghi M, Fitzgerald PB, et al. Reliability of motor evoked potentials induced by tran- scranial magnetic stimulation: the effects of initial motor evoked potentials removal. Basic Clin Neurosci 2017; 8: 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, et al. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ishii Y, Deie M, Adachi N, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjuvant for athletes. Sport Med 2005; 35: 739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wan JJ, Qin Z, Wang PY, et al. Muscle fatigue: general understanding and treatment. Exp Mol Med 2017; 49: e384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Giannotti E, Koutsikos K, Pigatto M, et al. Medium-/long-term effects of a specific exercise protocol combined with patient education on spine mobility, chronic fatigue, pain, aerobic fitness and level of disability in fibromyalgia. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 474029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fontaine KR, Conn L, Clauw DJ. Effects of lifestyle physical activity on perceived symptoms and physical function in adults with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12: R55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oyaizu T, Enomoto M, Yamamoto N, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen reduces inflammation, oxygenates injured muscle, and regenerates skeletal muscle via macrophage and satellite cell activation. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leach RM, Rees PJ, Wilmahurst P. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. BMJ 1998; 317: 1140–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Juan L, Peng L, Mengjun W, et al. Impact of hyperbaric oxygen on the healing of bone tissues around implants. Implant Dent 2018; 27: 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kalns J, Lane J, Delgado A, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen exposure temporarily reduces Mac-1 mediated functions of human neutrophils. Immunol Lett 2002; 83: 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. El-Shewy KM, Kunbaz A, Gad MM, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen and aerobic exercise in the long-term treatment of fibromyalgia: a narrative review. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 109: 629–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hägg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A; Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2003; 12: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Syrotuik J. Comparative study of self-rating pain scales in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Curr Med Res Opin 1999; 15: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bircan Ç, Karasel SA, Akgün B, et al. Effects of muscle strengthening versus aerobic exercise program in fibromyalgia. Rheumatol Int 2008; 28: 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Larsson A, Palstam A, Löfgren M, et al. Resistance exercise improves muscle strength, health status and pain intensity in fibromyalgia — a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Koo TK, Guo JY, Brown CM. Test-retest reliability, repeatability, and sensitivity of an automated deformation-controlled indentation on pressure pain threshold measurement. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2013; 36: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Carbonell-Baeza A, Romero A, Aparicio VA, et al. Preliminary findings of a 4-month Tai Chi intervention on tenderness, functional capacity, symptomatology, and quality of life in men with fibromyalgia. Am J Mens Health 2011; 5: 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA, Ortega FB, et al. Does a 3-month multidisciplinary intervention improve pain, body composition and physical fitness in women with fibromyalgia? Br J Sports Med 2011; 45: 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Latorre PÁ, Santos MA, Heredia-Jiménez JM, et al. Effect of a 24-week physical training programme (in water and on land) on pain, functional capacity, body composition and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013; 31(Suppl. 79): S72–S80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Skrypnik D, Bogdański P, Mądry E, et al. Effects of endurance and endurance strength training on body composition and physical capacity in women with abdominal obesity. Obes Facts 2015; 8: 175–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kampshoff CS, Chinapaw MJM, Brug J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of high intensity and low-to-moderate intensity exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors: results of the resistance and endurance exercise after chemotherapy (REACT) study. BMC Med 2015; 13: 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bellafronte NT, Serafini RKK, Chiarello PG. Relationship between total physical activity and physical activity domains with body composition and energy expenditure among Brazilian adults. Am J Hum Biol 2019; 31: e23317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Neumann L, Lerner E, Glazer Y, et al. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between body mass index and clinical characteristics, tenderness measures, quality of life, and physical functioning in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol 2008; 27: 1543–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bohannon RW, Crouch R. Minimal clinically important difference for change in 6-minute walk test distance of adults with pathology: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract 2017; 23: 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Richardson RS. What governs skeletal muscle V.O2max? New evidence. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000; 32: 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Latorre-Román P, Santos-Campos M, Heredia-Jimenez J, et al. Analysis of the performance of women with fibromyalgia in the six-minute walk test and its relation with health and quality of life. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2014; 54: 511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. King S, Wessel J, Bhambhani Y, et al. Validity and reliability of the 6 minute walk in persons with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 1999; 26: 2233–2237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Clarke-Jenssen AC, Mengshoel AM, Strumse YS, et al. Effect of a fibromyalgia rehabilitation programme in warm versus cold climate: a randomized controlled study. J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Russek LN. Chronic Pain. In: O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, Fulk G. (eds) Physical rehabilitation, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Fadavis, 2019, pp. 1081–133. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sanz-de la, Garza M, Giraldeau G, Marin J, et al. Influence of gender on right ventricle adaptation to endurance exercise: an ultrasound two-dimensional speckle-tracking stress study. Eur J Appl Physiol 2017; 117: 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mang CS, Brown KE, Neva JL, et al. Promoting motor cortical plasticity with acute aerobic exercise: a role for cerebellar circuits. Neural Plast 2016; 2016: 6797928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pearce AJ, Thickbroom GW, Byrnes ML, et al. Functional reorganisation of the corticomotor projection to the hand in skilled racquet players. Exp Brain Res 2000; 130: 238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. McDonnell MN, Buckley JD, Opie GM, et al. A single bout of aerobic exercise promotes motor cortical neuroplasticity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013; 114: 1174–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stavrinos EL, Coxon JP. High-intensity interval exercise promotes motor cortex disinhibition and early motor skill consolidation. J Cogn Neurosci 2017; 29: 593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mooney RA, Coxon JP, Cirillo J, et al. Acute aerobic exercise modulates primary motor cortex inhibition. Exp Brain Res 2016; 234: 3669–3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]