Abstract

Introduction:

A practice embarks on a radical reformulation of how care is designed and delivered when it decides to integrate medical and behavioral health care for its patients and success depends on managing complex change in a complex system. We examined the ways change is managed when integrating behavioral health and medical care.

Method:

Observational cross-case comparative study of 19 primary care and community mental health practices. We collected mixed methods data through practice surveys, observation, and semistructured interviews. We analyzed data using a data-driven, emergent approach.

Results:

The change management strategies that leadership employed to manage the changes of integrating behavioral health and medical care included: (a) advocating for a mission and vision focused on integrated care; (b) fostering collaboration, with a focus on population care and a team-based approaches; (c) attending to learning, which includes viewing the change process as continuous, and creating a culture that promoted reflection and continual improvement; (d) using data to manage change, and (e) developing approaches to finance integration.

Discussion:

This paper reports the change management strategies employed by practice leaders making changes to integrate care, as observed by independent investigators. We offer an empirically based set of actionable recommendations that are relevant to a range of leaders (policymakers, medical directors) and practice members who wish to effectively manage the complex changes associated with integrated primary care.

Keywords: organizational change management, delivery of health care, integrated, behavioral medicine, primary health care

A practice embarks on a radical reformulation of how care is designed and delivered when it decides to integrate medical and behavioral health care for its patients. Empirical research highlights the constellation of technical and operational changes involved in care integration. This includes hiring and training new personnel (Davis et al., 2015; W. Gunn & Blount, 2009); reconfiguring office space to facilitate teambuilding (R. Gunn et al., 2015); modifying clinician schedules, practice workflows, documentation, and information sharing processes (Cifuentes et al., 2015); and rethinking how professionals (e.g., medical clinicians, behavioral health providers) work together (Cohen, Davis, et al., 2015) and see themselves professionally (W. Gunn & Blount, 2009). Further, sustainable integration demands that senior executives change how care is financed, often in a fiscal environment in which medical and mental health care is funded from separate streams (Kathol, deGruy, & Rollman, 2014; Melek & Norris, 2008).

There are challenges involved in making the operational and cultural change to an integrated approach to care. This is highlighted by two recent editorials: one focuses on the important role of leadership when shifting to an integrated approach to care, and offers a theoretical framework for how to think about leadership during this change (deGruy, 2015), and the other offers insights into the role change facilitators might play in this practice transformation (Dickinson, 2015). These editorials align with the larger change management literature; the shift to integrated care is a multifaceted organizational change that requires leadership and change management (By, 2005; Cameron & Green, 2004; Cohen et al., 2004; Solberg, 2007; Solberg et al., 2000; Meyer, Brooks, & Goes, 1990), particularly for complex adaptive systems found in the health care. Organizational change management theories focus on different aspects of the change process, including rate of occurrence, how change comes about, and scale of the change (By, 2005), as well as leadership’s unique capacities and responsibilities in enabling change (Uhl-Bien, Marion, & McKelvey, 2007).

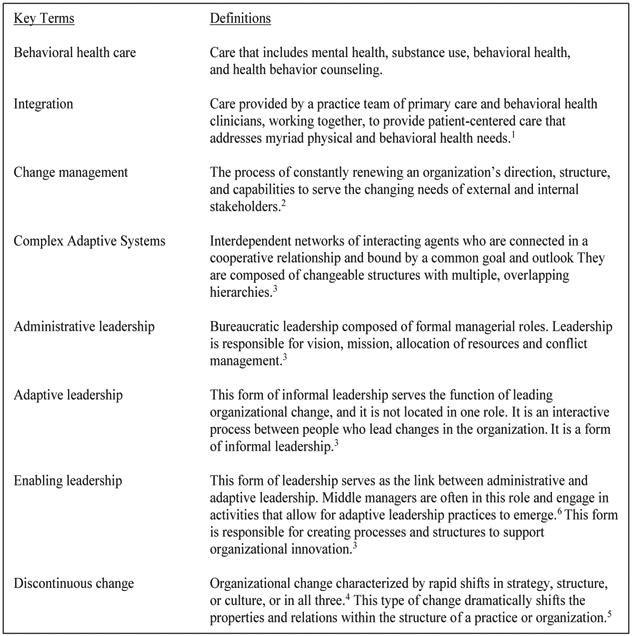

Across different industries, there is a 70% failure rate of change initiatives (Balogun & Hailey, 2004), which makes the empirical study of change management a salient topic for those integrating care. Yet, there is little empirical evidence that identifies the change management strategies employed among “real-world” practices as they integrate care. This paper identifies approaches to change management among a group of 19 practices located in the United States that were at different stages of integrating care in their organizations and attempts to connect these approaches to prevailing theoretical models of organizational change, and expose the actual behaviors of leaders striving to manage change in their organizations. Figure 1 contains a definition of terms used in this manuscript.

Figure 1.

Key terms. Note. 1Green and Cifuentes (2015). 2 Moran and Brightman (2005). 3 Uhl-Bien, Marion, and McKelvey (2007). 4 Grundy (1993). 5 Meyer, Brooks, and Goes (1990). 6 Uhl-Bien, Marion, and McKelvey (2007).

Method

Sample

The sample for this study was 19 practices integrating care. Eleven practices were located in Colorado and participated in Advancing Care Together (ACT). ACT was an initiative funded by The Colorado Health Foundation that focused on practices actively working to make the transition to delivering integrated care (Cohen, Balasubramanian, et al., 2015). Eight practices were located across the United States and participated in the Integration Workforces Study (“Workforce” study). Workforce was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the California Mental Health Services Authority Foundation and Maine Health Access Foundation. In Workforce, an expert panel selected practices that were further along in changing their delivery system to integrate care for patients, and were included for their integration expertise (Cohen, Davis, Hall, Gilchrist, & Miller, 2015).

Data Collection

A multidisciplinary research team with expertise in integrated care, primary care, communication, medical sociology, public health, and health psychology conducted this study. A subset of this team had extensive experience collecting and analyzing qualitative data, and collected the data for ACT and Workforce using comparable methods. We observed the ACT practices (2011–2013) and the Workforce practices during 2012–2013. Site visits were 2 to 5 days in length, which was driven by the number of researchers attending the visit and practice size. During site visits, the data collection team observed practices’ operations, including administrative meetings, delivery of clinical care (including visits with patients), and interactions between clinicians and staff. We conducted semistructured interviews (8–12 staff at each practice) with staff and leaders at all levels of the organization (e.g., Chief Executive Officer [CEO], Director of Integration, team manager); the number of interviews conducted was influenced by practice size and staff diversity.

Data Management

Notes taken by the data collection team during site visits were expanded into rich observational fieldnotes within 24–48 hr of the end of the visit. Interviews were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and checked for accuracy. Interview transcripts and fieldnotes were deidentified and entered into Atlas.ti (Version 7.0, Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for data management and analysis.

Analysis

We did not have an a priori theory or model for change management or leadership to inform or motivate our analysis. Instead, we examined data in order to understand what the participants in our study were saying and demonstrating through their behaviors about organizational change and improvement, using Crabtree and Miller’s (1999) analysis process. We started by describing the data for a single practice, reading fieldnotes and interview transcripts together to gain an appreciation of the practice’s approach to change management, and how this approach varied within an organization. This included regular meetings to organize segments of text and tag them with descriptive names. When data for all of the practices were analyzed, we shifted to a cross-practice comparative analysis whereby we examined, more deeply, how change management manifests across organizations, with a particular focus on practices newer to integrating care (typically ACT practices) with those with more experience with integration (typically Integration Workforces Study practice). This comparison surfaced the absence and presence of change management strategies critical to integration. Our final step was to make connections with existing literature, which allowed us to enrich and extend study findings.

The Institutional Review Boards at Oregon Health & Science University and the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston approved this study.

Results

Participating practices varied in ownership, size, location, and staffing (Table 1), as well as experience (range: 1–20 years) and approach to integration (Cohen, Balasubramanian, et al., 2015). We identify five key areas of focus for those leading and managing the change to integration: (a) advocate for a mission and vision focused on integrated care; (b) foster collaboration, with a focus on population care and a team-based approach; (c) attend to learning, viewing the change process as continuous, and creating a culture of change that promoted reflection and continual improvement; (d) use data to manage change; and (e) develop approaches to sustainably finance integration. Table 2 is an exhaustive list of the change management strategies we observed in each of these five areas.

Table 1.

Practice Characteristics

| Clinic ID | Ownership | Setting | Annual patient visits, n |

Practice characteristics: PC/MH/Both |

PCC FTE | BHC FTE | Ratio (PCC:BHC) |

Funding designation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Private, nonprofit | Urban | 90,480 | Both | 22.5 | 1.0 | 22.5:1 | FQHC/CMHC |

| 2 | Private, nonprofit | Suburban | 10,972 | Both | 6.5 | 3.2 | 2.0:1 | FQHC/CMHC |

| 3 | Private | Urban | 104,520 | PC | 48.2 | 17.4 | 2.8:1 | Government |

| 4 | Private, nonprofit | Suburban | 14,924 | PC | 11.0 | 2.0 | 5.5:1 | FQHC |

| 5 | Hospital system | Urban | 10,400 | PC | 5.8 | 1.6 | 3.6:1 | None |

| 6 | Private, nonprofit | Suburban | 10,693 | PC | 1.2 | 3.8 | .3:1 | FQHC |

| 7 | Clinician | Suburban | 31,720 | PC | 10.0 | .5 | 20.0:1 | None |

| 8 | Private, nonprofit | Urban | 102,960 | PC | 9.9 | 2.9 | 3.4:1 | FQHC |

| 9 | Clinician | Rural | 4,680 | PC | 2.0 | .5 | 4.0:1 | None |

| 10 | Clinician | Suburban | 15,600 | 4.8 | .5 | 9.6:1 | None | |

| 11 | Hospital system | Rural | 27,000 | PC | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0:1 | None |

| 12 | Hospital system | Suburban | 8,372 | PC | 3.2 | .9 | 3.5:1 | FQHC |

| 13 | Clinician | Urban | 47,476 | PC | 13.6 | 1.0 | 13.6:1 | None |

| 14 | Hospital system, HMO, nonprofit | Suburban | 27,748 | PC | 21.9 | .6 | 36.5:1 | None |

| 15 | Government | Urban | 159,096 | Both | 70.0 | 5.6 | 12.5:1 | Government |

| 16 | Hospital system | Suburban | 17,680 | PC | 9.0 | 1.4 | 6.4:1 | FQHC |

| 17 | Private, nonprofit | Rural | 31,200 | MH | 6.0 | 2.0 | 3.0:1 | CMHC |

| 18 | Private, nonprofit | Suburban | 4,732 | MH | .4 | 22.8 | .02:1 | CMHC |

| 19 | Private, nonprofit | Rural | 7,904 | MH | 2.2 | 7.9 | .28:1 | CMHC |

Note. PC = primary care; MH = mental health; PCC = primary care clinician; BHC = behavioral health clinician; FTE = Full time employees; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center; CMHC = Community Mental Health Center.

Table 2.

Empirically-Derived Strategies for Managing Change to an Integrated Care Approach

| Advocating a vision and mission for integrationa |

| Talk about the vision and tell stories about how the practice was guided to take action because of its vision |

| Spread the mission and vision: write it down, hang it up on the walls, tell it to patients, new hires |

| Engage practice members in developing a vision |

| Develop transparency about actions the practice takes and how they align with the vision |

| Identify leaders to implement new care processes and to promote organizational cultural change to align with vision and mission |

| Fostering collaborationa |

| Specify staff needed to support integrated care and clarify rolesb,c |

| Create structured and unstructured meetings for integrated care teams to collaborate on patient care |

| Put integrated care teams in close proximity to each other (same office)b, d |

| Hire adequate staff to meet patient need |

| Develop a schedule to accommodate warm hand-offs which requires BHC flexibility |

| Establish a clear path for patients with longer-term behavioral health need (providing care for higher-needs patients can limit integration)c |

| Use single EHR system and share information among medical and behavioral health cliniciansb,e |

| Have teams model how to work effectively to deliver integrated caref |

| Include professionals on the team that are aligned with the vision of integrated care |

| Attending to staff learning needsf |

| Learn from mistakes and talk about mistakes without repercussion |

| Develop culture where everyone is prepared to revise processes, when needed |

| Provide training in integration by internal experts, external consultants, or have staff participate in external training programs |

| Develop a training manual about integration: this aligns the team and communicates information to new hires |

| Invest in on-boarding new staff, including shadowing of all aspects of integrated care to train new hires |

| Provide ongoing, multidisciplinary developmental opportunities to foster cross-professional learning |

| Develop mentoring opportunities for clinicians to help them integrate care |

| Using data to manage changec,e |

| Upgrade EHR system with improved templates and data reporting tools |

| Use of a single EHR by all integrated care team members |

| Customize templates to allow your team to document clinical information and extract these data into reports |

| Use EHR reports to monitor performance on metrics that are indicators of quality integration |

| Financing integrationg |

| Engage external actors to collaborate on negotiating payment strategies for BHCs |

| Non fee-for-service, alternative payment methods allow BHCs to avoid volume-based payments and distinct “mental health” coding categories |

| Make sure there are incentives in place to encourage primary care clinicians to work with behavioral health |

| Consider the impact behavioral health on the clinical delivery of care |

Note. EHR = electronic health record; BHC = behavioral health clinician.

Advocating a Mission/Vision

ACT practices, many of which were starting the shift to integrating care, had not yet developed a clear mission for integration. At funder-hosted learning collaboratives, practice leaders talked about feeling lonely, unsupported, and having a lack of direction with regard to their integration efforts. Part of the trouble was maintaining the status quo while, at the same time, trying to undo it:

… Part of what’s getting in the way is not really the trouble of integration, but actually having to run a community mental health center at the same time that you’re trying to create an integrated health care organization… . This was my personal dilemma … keeping the day-to-day community mental health organization running, which means continuing to meet your contract obligations, continuing to have crisis care, and doing all the things [our organization] has done for 50 years … while at the same time trying to undo all of that and create something completely different … that’s one piece I would say is definitely part of the shift to integration as a challenge. (Director of Behavioral Health Integration interview, Practice 19)

Administrative (i.e., system leaders) were often absent from these collaboratives. Yet, as we learned from Workforce practices, their vision for the organization’s mission was determinative. For example, Workforce Practice 2 was a system where administrative leaders (e.g., CEO, CFO) identify the “what” for the organization, which was achieving population health, with integration as the means to accomplishing it. Practice leaders, who were responsible for achieving that mission, described the importance of clarity in direction: “It’s all about mission… . People believe in our mission of outreach to populations that don’t have other opportunities for care … it’s really more about that than integration” (CEO interview, Practice 2). The presence of a clear and consistent organization mission necessitating integration was critical. When absent, practice leadership felt unsupported and undirected.

Fostering Collaboration

Part of managing change was helping practice members implement a new integrated practice, which involved fostering new collaborations among team members by specifying the expertise needed to support integrated care and creating times for collaboration when staff with different roles can work together. As one ACT practice reported, all-staff meetings helped with “getting on the same page and into a rhythm and flow” (Primary Care Physician interview, Practice 13). Both ACT and Workforce practices described how successful integration hinged on integrating the cultures of primary care and mental health. One ACT respondent addressed the cultural gap in this way:

… we now know it’s our responsibility to bridge the cultures between mental health and primary care. Developing collaborative guidelines will start the map of communication between the two cultures. We are recognizing the differences between mental health and primary care and are finding a respect to the strengths and weaknesses between the two. (Program Report, Practice 10)

Bridging the cultural differences between professions required helping change their “framework” and “encouraging” practice staff to address conflict when, for example, a physician resisted change by practicing alone, and not appropriately including the behavioral health clinicians (BHCs) in the patient care process. At these moments, having collaborative guidelines, a clear organization mission, and adaptive leadership was crucial to helping foster collaboration and empower practice staff to stand for integrated practice.

Attending to Learning

Mentoring and providing ongoing training opportunities to staff to support technical capacity was another important aspect of change management. Participants highlighted the need to enable training and monitoring of new and existing staff: “I have three new behavioral providers. They’re all full-time. My concern is making sure that the medical providers really get the role of the BHC, and really embrace it and adopt it so that they utilize it to their advantage and the patient’s advantage” (Practice Administration interview, Practice 3).

We also observed the importance of learning from mistakes, which included leadership’s adaptive capacity to solicit and revise processes based on staff input and to have a high tolerance for mistake-making. As stated in an ACT learning collaborative: the “best lessons (solutions) come from failures.” Workforce practice members echoed this, as exemplified in the following description of a staff meeting:

We start off by saying, ‘What’s working well?’ That warms up the group, and I’m writing things down or scribbling on my computer. Then, ‘Okay, what’s not working so well? And they’ll say whatever needs to be improved. Usually, that’s longer than what’s good. People seem to be able to articulate, ‘We need this or we need that.’ And then I say, ‘Okay, tell me what’s really messed up?’… . Then what happens is I take all that and distribute it among our executive staff, and we go through it… . We also use it in our strategic planning… . We’ll say, ‘Out of all these comments, here are five priorities for 2013–2015. (Director of Integration interview, Practice 3)

Also crucial was a tolerance for risk-taking, and change managers created a culture in which experimenting, and mistake-making were tolerated.

Using Data to Manage Change

Those managing change recognized that the capacity to document and extract data from the electronic health record (EHR), and to adjust plans based on data was an inherent part of the improvement process. Most Workforce practices were able to leverage data from the EHR to assess patient, provider, and practice-level performance indicators for integrated care delivery. As the Quality Improvement Coordinator at one Workforce practice expressed,

We did a lot with the QI committee, making sure that the resources are in the primary care organizations, and that the information that they’re needing, that we’re documenting properly in the EHR, that all the information is there for them to be able to mine that data… . We’ll choose a weakness or a QI measure that we need to work on. We set goals, and then at our QI committee meetings we look at those goals. We look at the data and determine where we’re at. We celebrate success, or we create a corrective action plan if needed and monitor that, trend it… . We’re constantly monitoring. It’s a fluid process. (Quality Improvement Coordinator, Practice 2)

In contrast, ACT practices encountered issues with adapting EHRs to manage the delivery of integrated care:

Collecting numbers is the next step of movement. [Name] has been looking at UW IMPACT stuff, their flow, teambuilding, and so forth. It’s very concrete with good administrative tools to identify and diagnose patients. She realizes that they have done quite a bit and tracking the treatment outcomes is where there is more to be done. (diary entry, Practice 9)

While ACT leaders recognized the importance of using data to manage the change to integration, they did not yet have the capacity to do this. They looked to more experienced practices for guidance helping to set the course of their future data efforts.

Financing Integration

Managing the change to an integrated practice required establishing a financial model to support integration. In ACT practices, securing grant funding was cited as a necessary step to begin integration efforts; however, participants had concerns regarding how grant funding would sustain integration efforts:

I worry a little bit about what’s going to happen when… . What happens when the money dries up … when the [Name] initiative is gone. Is it really going to pay for itself? Can we really afford to do it? That is probably the biggest concern.” (Primary Care Physician interview, Practice 19)

Another participant highlighted her practice’s use of creative strategies to finance integration, which included sponsoring a golf tournament fundraiser to pay for their BHC (Medical Director interview, Practice 10).

In Workforce practices, we saw advanced financing strategies, such as building relationships with health plans to negotiate payment for integrated services: “Clinic administration has relationships with payers. We’re in what we call shared savings arrangements. So, if we can save money, we split that with the payers. It’s more technical than that, but basically that’s the bottom line” (Practice Administrator interview, Practice 5). Health care systems negotiated with payers; this required being large enough to be noticed, having data about practice performance (see above), and possibly having administrative leaders (CEO, CFO) with a regional reputation. The arrangements established with payers helped pay for the infrastructure and personnel for integrated teams. For example, one CFO discussed payment arrangements with a large insurance company in this way:

A long time ago we set in our strategic plan that we wanted to be big enough to be noticed, or to be able to negotiate… . With the Blue Cross/Blue Shield side, and then a couple of other payers, we have been able to work out a care coordination fee. It is similar to a case rate, but it is an add-on fee for service. So, we bill as a fee for service, the CPT codes… . But then if we are seeing them on the behavioral side of the house, then we get this additional care coordination fee to help offset some of that infrastructure. (CFO interview, Practice 2)

Additionally, a small number of practices had secured federal designations that helped offset costs for delivering integrated care—and in some cases, where there was a Federally Qualified Health Center-Community Mental Health Center hybrid organization, provided clear pathways for patients with more severe behavioral needs.

Discussion

These empirical findings expose the actual behaviors of leaders striving to integrate care and who are responsible for managing change at multiple levels in their journey to integrate care. These observed behaviors underscore the crucial importance of skillful management of change and constitute five achievable areas in which change can be managed in local practices. Interestingly, our findings are generally consistent with prior publications about leadership in general and practice innovations in particular.

In the larger body of change management literature, the move to deliver integrated care is a “discontinuous change” that includes modifications in strategy, structure, and culture (By, 2005; Meyer et al., 1990) and dramatically transforms the properties and relations within the structure of a practice (Grol, Bosch, Hulscher, Eccles, & Wensing, 2007; Solberg et al., 2000). We identified five empirically informed areas to be addressed when transforming to an integrated health care organization that map well to existing theories of organizational change, as well as practical recommendations for managing change in these area. The areas included the ability to advocate a shared organizational mission (Beer, 2003; Berwick, 1989; By, 2005; Garside, 1998); foster collaboration among team members, and create formal structures to facilitate understanding of how integrated teams work together (Grol et al., 2007; Solberg et al., 2000); attend to learning, which included viewing the change process as never-ending and creating a culture that was committed to organizational reflection by soliciting input and data from all staff on the gaps between the change initiative and the implementation process (Batalden & Davidoff, 2007; Berwick, 1989; Detert, Schroeder, & Mauriel, 2000; Garside, 1998); and a high-tolerance for mistake-making and risk-taking (Berwick, 1989; Detert et al., 2000) while providing mentorship and training to develop individuals’ technical capacity.

In practices with more experience integrating care, we found that the change to integrate care required multilevel leadership (Batalden & Davidoff, 2007; Beer, 2003; Garside, 1998; Solberg, 2007). We also found that enabling and adapting leadership behaviors were not tied to a specific role or person, but emerged across people in these organizations. Administrative, adaptive, and enabling leadership correspond quite closely with to the three types of leadership described in complexity leadership theory (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). We heard about the importance of administrative leadership, which entailed being responsible for creating a vision and mission for integration. Administrative leadership also involved acquiring resources and creating a sustainable plan for financing integrated care. We observed both the presence and absence of adaptive and enabling leadership. Adaptive leadership involved leaders at all levels taking responsibility for translating the organizational mission and vision into action by fostering collaboration (e.g., creating schedules that allowed interaction), attending to staff learning needs (e.g., encouraging mistakes and learning from them, maintaining a low threshold for revising processes as needed), and for using data to manage change. Enabling leadership involved the use of resources to create the structures and process that make integration possible (e.g., specifying and hiring needed staff, creating physical space conducive to collaboration, ensuring that the EHR and all other forms of professional communication are accessible, creating training materials and providing professional educational, developmental and mentoring opportunities related to integration).

This study has several limitations. First, in qualitative work, it is important that the beliefs and preconceptions of one individual do not unduly influence what is observed and reported. We addressed the potential of research bias through triangulation in the data collection and analysis process. We had multiple researchers from different backgrounds collect and analyze data. This ensured the views of those we observed and interviewed, rather than our own views, directly informed this work. Second, it is not practical to observe practices through the lengthy transformation to delivering integrated care, which those we interviewed remarked was a never-ending process. We do not claim to have captured all of the key areas of change management; we are sure that there are others. However, the combination of ACT practices that were in the early phases of change to integration and the Workforce practices that were in a later phase of change mitigated this challenge by offering insights into leadership and change management at different points in the change process. Third, while we interviewed key stakeholders (CEOs, CFOs, and CCOs) across the practices, we did not spend time observing these leaders. This has two important implications. While we were able to observe the effects of executive leadership in other areas of the organization, we did not see their leading in action. Second, our findings lack detail into some of the important work executives do, such as negotiating with payers to secure resources for integration. How executives establish financing for integration was outside the purview of this study, but would be an interesting focus for future research.

Conclusion

We identify five domains of change management, link these to empirically grounded recommendations, and map them to contemporary theories of organizational change. These practical recommendations will help people on the ground to continue the work of leading and managing the change to integration, despite countervailing tensions in the external environment. By offering a framework for understanding the elements of complex change, local practice-level solutions can achieve a higher uniformity, and begin to add up to a coherent, comprehensive rationale to create definitive solutions to our fragmented primary care system.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by grants from the Colorado Health Foundation (Grant CHF-3848), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant 8846.01-S01), the California Mental Health Services Authority Foundation (Grant AWD-131237), and Maine Health Access Foundation (Grant 2012FI-0009). The authors are thankful to the participating practices.

Contributor Information

Khaya D. Clark, Oregon Health & Science University.

Melinda Davis, Oregon Health & Science University and Oregon, Rural Practice-Based Research Network, Portland, Oregon.

Benjamin F. Miller, University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Larry A. Green, University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Frank V. de Gruy, III, University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Deborah J. Cohen, Oregon Health & Science University.

References

- Balogun J, & Hailey H (2004). Exploring strategic change. London, UK: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Batalden PB, & Davidoff F (2007). What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Quality & Safety in Health Care, 16, 2–3. 10.1136/qshc.2006.022046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer M (2003). Why total quality management programs do not persist: The role of management quality and implications for leading a TQM transformation. Decision Sciences, 34, 623–642. 10.1111/j.1540-5414.2003.02640.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM (1989). Continuous improvement as an ideal in health care. The New England Journal of Medicine, 320, 53–56. 10.1056/NEJM198901053200110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- By R (2005). Organisational change management: A critical review. Journal of Change Management, 5, 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron E, & Green M (2004). Making sense of change management: A complete guide to models, tools & techniques of organizational change. London, UK: Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL (1999). Doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes M, Davis M, Fernald D, Gunn R, Dickinson P, Cohen DJ (2015). Electronic health record challenges, workarounds, and solutions observed in practices integrating behavioral health and primary care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28(Suppl.), s63–s72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Davis M, Hall J, Gunn R, Stange KC, … Miller BF (2015). Understanding care integration from the ground up: Five organizing constructs that shape integrated practices. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28, S7–S20. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Davis M, Balasubramanian BA, Gunn R, Hall J, deGruy FV III, … Miller BF (2015). Integrating behavioral health and primary care: Consulting, coordinating and collaborating among professionals. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28 (Suppl. 1), S21–S31. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, McDaniel RR Jr., Crabtree BF, Ruhe MC, Weyer SM, Tallia A, … Stange KC (2004). A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. Journal of Healthcare Management, 49, 155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Balasubramanian B, Waller E, Miller B, Green L, & Cohen D (2013). Integrating behavioral and physical health care in the real world: Early lessons from Advancing Care Together. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 26, 588–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MM, Balasubramanian BA, Cifuentes M, Hall J, Gunn R, Fernald D, … Cohen DJ (2015). Clinician staffing, scheduling, and engagement strategies among primary care practices delivering integrated care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28, S32–S40. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deGruy FV III. (2015). Integrated care: Tools, maps, and leadership. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28, S107–S110. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detert J, Schroeder R, & Mauriel J (2000). A framework for linking organizational culture and improvement initiatives in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 25, 850–863. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson WP (2015). Strategies to support the integration of behavioral health and primary care: What have we learned thus far? Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28, S102–S106. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garside P (1998). Organisational context for quality: Lessons from the fields of organisational development and change management. Quality in Health Care, 7, S8–S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LA, Cifuentes M (2015). Advancing care together by integrating primary care and behavioral health. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28(Suppl.), s1–s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol RP, Bosch MC, Hulscher ME, Eccles MP, & Wensing M (2007). Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Quarterly, 85, 93–138. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00478.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy T (1993). Managing strategic change. London, UK: Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn R, Davis MM, Hall J, Heintzman J, Muench J, Smeds B, … Cohen DJ (2015). Designing clinical space for the delivery of integrated behavioral health and primary care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28, S52–S62. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn WB Jr., & Blount A (2009). Primary care mental health: A new frontier for psychology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 235–252. 10.1002/jclp.20499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Cohen D, Davis M, Gunn R, Blount A, Pollack D, Miller W, Smith C, Valentine N, & Miller B (2015). Preparing the workforce for behavioral health and primary care integration. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28(Suppl.), S41–S51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathol RG, Degruy F, & Rollman BL (2014). Value-based financially sustainable behavioral health components in patient-centered medical homes. Annals of Family Medicine, 12, 172–175. 10.1370/afm.1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JW, Brightman BK (2001). Leading organizational change. Career Development International, 6, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Melek S, & Norris D (2008). Chronic conditions and comorbid psychological disorders. Retrieved from us.milliman.com/…/research/…/chronic-conditions-and-comorbid-psychological-disorders/ [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Brooks G, & Goes J (1990). Environmental jolts and industry revolutions: Organizational responses to discontinuous change. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg LI (2007). Improving medical practice: A conceptual framework. Annals of Family Medicine, 5, 251–256. 10.1370/afm.666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg LI, Brekke ML, Fazio CJ, Fowles J, Jacobsen DN, Kottke TE, … Rolnick SJ (2000). Lessons from experienced guideline implementers: Attend to many factors and use multiple strategies. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 26, 171–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl-Bien M, Marion R, & McKelvey B (2007). Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 298–318. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace N, Cohen D, Gunn R, Beck A, Melek S, Bechtold D, & Green L (2015). Start-up and ongoing practice expenses of behavioral health and primary care integration interventions in the Advancing Care Together (ACT) program. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 28(Suppl.), S86–S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]