Highlights

-

•

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the primary clinical emphasis has shifted to optimizing community health.

-

•

Scarce resources should be allocated to maximize benefit without unfairly affecting any group.

-

•

Healthcare systems should consider adopting a formal, tier-based response to COVID-19 related demand on resources.

-

•

Clinicians should use principles of high-stakes communication to guide care planning during the pandemic.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted dramatic changes in the clinical care environment. These changes substantially affect how patients with gynecologic cancers interact with the health care system, and may require gynecologic cancer professionals to alter their approach to providing medical and surgical care. Additionally, healthcare institutions may call on gynecologic oncologists to represent the interests of their patients during deliberations regarding institutional allocation of scarce healthcare resources. In this article, we provide an overview of ethical considerations underlying gynecologic cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic; discuss how clinical practices may implement crisis standards of care, including allocation of scarce medical resources; and address how COVID-19 has impacted palliative care in gynecologic oncology, with a focus on critical conversations. This article reflects the content of the SGO COVID-19 Webinar entitled “Ethical Considerations and Critical Communication During COVID-19” delivered on April 16, 2020.

2. Ethics

2.1. Ethical principles guiding clinical care during the COVID-19 pandemic

Clinical decision-making for cancer care generally involves optimizing outcomes of individual patients within the context of a patient-physician relationship. Treatment plans are selected based on clinical circumstances and patients' relevant preferences and values. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid shift from prioritizing the outcomes of individual patients to optimizing the health of the community. Consequently, healthcare systems have adjusted clinical operations to minimize spread and morbidity associated with COVID-19, and to preserve their ability to provide acute care in the context of increased demand.

These changes have been disruptive to usual cancer care in at least three ways. First, previously available treatment options may be altered or restricted by institutional or regulatory groups. For example, expeditious primary surgical treatment for a suspected malignancy may not be possible due to restrictions on operating room usage. Second, institutional policies related to morbidity mitigation or resource allocation may appear to devalue an individual patient's preference in deference to the common good, an approach that may conflict with the standard approach to shared decision-making. For example, despite the benefit of bedside support from family and loved ones, strict visitation restrictions may be imposed on hospitalized patients with cancer to prevent transmission of COVID-19 to patients and healthcare staff. Third, access to clinical trials may be significantly limited as institutions divert resources to managing clinical surges.

Restrictions on clinical cancer care may be ethically difficult for healthcare professionals and patients and may cause patients and physicians to feel a loss of control. This, in turn, puts physicians at risk for burnout and patients at risk for demoralization [1,2]. Gynecologic oncologists should understand their role as part of a communal effort by healthcare professionals to protect as many members of the public as possible during the pandemic, while still advocating for gynecologic cancer patients to receive the best available care. Likewise, pandemic-related alterations in cancer care may be explained to patients as maximizing healthcare systems' ability to care for those in need, as well as minimizing morbidity of COVID-19 in high-risk populations, such as persons with cancer. Although patients may be understandably frustrated by prioritization of the communal good, gynecologic oncologists should attempt to preserve the patient-physician relationship by emphasizing a continuing commitment to provide the best care possible under difficult circumstances. Physicians should consider seeking assistance from colleagues or their clinical practice with any particularly difficult patient interaction or clinical decision.

Importantly, although the environment within which gynecologic cancer care is provided has changed, the fundamental obligations of physicians to care for their patients has not. In general, gynecologic oncologists may not decline to care for a patient solely based on the patient's infectious disease status. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of contracting an infectious disease must be balanced against several other considerations. First, healthcare professionals may be a scarce resource in some clinical settings, and physicians should consider how they may best promote the health of their patients and the community. Accordingly, physicians who meet criteria for removal from direct patient care based on symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, should do so expeditiously. Likewise, physicians who are at elevated risk for morbidity from COVID-19 should work with their clinical practices to determine the most appropriate setting in which to provide patient care.

Physicians are professionally obligated to be willing to take on some risks to themselves during patient care; however, this obligation is not unlimited. Clinical practices therefore may not require or expect physicians to provide care without adequate personal protective equipment (PPE). Some physicians, after careful consideration, may choose to provide care to high-risk patients without adequate PPE; however, they are not ethically obligated to do so. This decision is highly individualized, and should balance physicians' desire to provide care with the likelihood of subsequent personal morbidity, risk of subsequent transmission of COVID-19 to close contacts, and implications for physicians' ability to care for future patients. Clinical practices should not exert social or economic pressure on physicians to provide clinical care without adequate PPE [3].

2.2. General principles for allocation of scarce healthcare resources

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems are under pressure to develop and implement “crisis standards of care” that outline procedures for disaster response, including allocation of resources for which demand is expected to exceed supply [4,5]. Although much attention has been paid to the possibility of a shortage of mechanical ventilators for critically ill patients, examples of scarce resources also include medication for supportive care (e.g., sedatives and vasopressors), intensive care unit beds, operating room time, and healthcare professionals able to manage a potential surge in demand for acute care. Crisis standards of care may also proactively include contingencies for vaccination and treatment modalities still in development.

In general, policies for allocation of scarce resources should seek to maximize the benefit of resource use without unfairly benefiting or disadvantaging any group of patients [4,6]. Estimation of benefit is tightly linked to the prognosis of individuals who receive scarce resources; policies should consider both lives saved as well as morbidity prevented. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scale has been frequently utilized as a standardized assessment of prognosis in critically ill adults; alternate scales should be used for pediatric patients [7,8]. For critical care resources, survival-to-discharge may be the most appropriate metric of benefit. For scarce preventative resources such as powered air purifying respirators (PAPRs) or N95 masks, prevention of COVID-19 related morbidity may be more appropriate.

If the likelihood of benefit is equivalent, consideration may be given to prioritizing sicker patients as having a more urgent need, younger patients as having the potential for more life-years saved, and healthcare professionals as reciprocity for their service to the public and potential to provide patient care after recovery [4,9]. Institutions have an obligation to avoid exacerbating existing inequities in healthcare through resource allocation policies; for example, while a “first-come, first-served” policy may seem equitable, patients without the ability to access healthcare may be unfairly disadvantaged. Additionally, policies should not overtly discriminate through exclusion criteria. For example, advanced age should not itself exclude patients from treatment or critical care. Neither should a history of cancer be a blanket exclusion, because some malignancies (e.g., early stage gynecologic cancers) may have a good long-term prognosis. Likewise, blanket do-not-resuscitate orders for patients with COVID-19 are unethical when they do not consider patients' prognoses or preferences. Health systems should routinely monitor implementation of crisis standards of care to ensure that they are being applied equitably [10].

2.3. Operationalizing crisis standards of care

Operational support for hospitals implementing crisis standards of care may be found through Incident Command System Resources published by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) [11]. The Incident Command System is intended to facilitate institutional response to a crisis by integrating the functional areas of command, planning, operations, logistics, intelligence & investigations, finance, and administration. In general, the Incident Commander has overall responsibility for setting institutional objectives in response to the crisis. The Planning Section develops plans to accomplish the objectives and the Operations Section organizes and directs institutional resources to implement the response plans. The Logistics Section provides resources and services needed to support institutional response, and the Finance/Administration Sections monitor costs and provide oversight. Intelligence and Investigations provide up-to-date information regarding the crisis and the institutional response to inform the activities of the other sections [12].

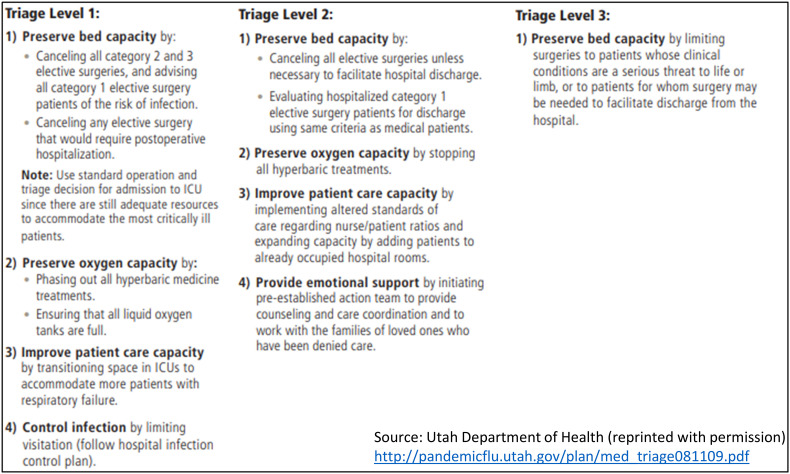

Hospitals may also find it useful to implement a formal, tiered response to demand on resources prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Implementation of crisis standards of care, including protocols for scarce resource allocation, may be guided by the current institutional triage level. The Utah Department of Health adapted a tiered approach to the management of hospital resources created during the 2009 influenza pandemic to the current COVID-19 pandemic: During Triage Level 1, early in the pandemic, emergency departments experience increasing numbers, and hospitals begin to consider maximizing bed capacities. During Triage Level 2, emergency departments are overwhelmed and despite hospitals' surge to maximum bed capacity, there are more patients requiring admission or critical care resources than the hospital has available. Hospital staff absenteeism is 20–30%. In Triage Level 3, hospitals have already made accommodations to board multiple patients per room, implemented protocols for allocation of scarce resources, and altered staffing assignments to account for upwards of 30% absenteeism [13]. Examples of hospital administrative responses to each Triage Level are depicted in Fig. 1 , though institutional response to demands on resources will undoubtedly vary by local resources, disease burden, and evolving understanding of the clinical needs of patients with COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Examples of tiered institutional response to demand on resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Health care systems should ensure that protocols allow for uniform application and do not force physicians to make bedside decisions about resource allocation on a case-by-case basis. Institutional multidisciplinary triage teams should be responsible for case review, assignment of a priority score, and consensus decision-making regarding allocation of scarce resources, such as ventilators. Triage teams should have a diverse membership, including physicians, nurses, administrators, and ethicists within the hospital community. These teams should not be involved in direct clinical care and should be blinded to patient characteristics associated with implicit bias (e.g., race or insurance status). Many institutions have implemented priority scores that are a composite of prognostic factors, “tiebreaker” characteristics, and other relevant factors [4,14]. Even if not directly involved in resource allocation decisions, treating physicians (including oncologists) may be best placed to communicate triage decisions to patients, given their existing therapeutic relationships.

The ideal interval for re-evaluating the clinical status of patients receiving critical care for COVID-19 for the purposes of re-allocating scarce resources is unknown. While institutional policies should aim to capture clinically meaningful changes in prognosis, re-calculation of priority scores too frequently may needlessly stress the triage system, healthcare professionals, patients, and their families. Re-allocation of scarce critical care resources, including ventilators, may be exceptionally difficult, but is ethically justifiable if the likelihood of benefit from continued use is low [4].

Gynecologic oncologists have an ethical obligation to ensure that their patients' prognoses are accurately represented in priority scores. While patients with active malignancy may by default be assigned a lower priority score based on a presumption of poor life expectancy, some patients with gynecologic cancers may in fact have life expectancy measured in years. Furthermore, some patients' disease (e.g., early stage endometrial cancer) may not be life-limiting. Likewise, patients with gynecologic malignancies, including patients in survivorship, should not be excluded from research related to COVID-19 without sound scientific justification. Gynecologic oncologists should continue to advocate for representation of these patients in clinical trials.

3. Palliative care and critical communication

Palliative care is specialized medical care for patients with serious illness focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness, with the goal of improving quality of life for both patient and family [15]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, gynecologic oncologists should provide timely, high quality, individualized palliative care to patients to help them navigate their cancer diagnosis and the risk of another potentially life-limiting illness, COVID-19 [16,17]. Communication scenarios & skills particularly critical to COVID-19-related conversations include delivering bad news, and advance care planning. Importantly, the following principles apply both to in-person and virtual (i.e. telehealth) conversations, though the latter modality may pose communication challenges for both patient and physician.

3.1. Conveying bad news and responding to emotion

Gynecologic oncologists commonly deliver bad news to patients, including initial cancer diagnoses or evidence of disease progression while on therapy. During the COVID-19 pandemic, examples of bad news might also include postponement of surgery or inability to provide in-person clinic visits. In the extreme, gynecologic oncologists may be asked to communicate that potentially life-sustaining resources (e.g., ventilators) are not available within crisis standards of care. General frameworks for sharing bad news are comprehensively covered elsewhere [16,18].

Schwartz & Pines suggest that “we are dealing with two contagions – [COVID-19] itself and the emotions it generates.” [19] Responding to emotion is critical when discussing bad news. The serious illness communication nonprofit VitalTalk recommends use of NURSE statements—Naming, Understanding, Respecting, Supporting and Exploring—to express empathy for the expected emotional responses to bad news [20]. A simple Naming statement for responding to emotion is “This is hard,” acknowledging the fact that dealing with bad news related to cancer care during a global pandemic is challenging. Additional examples of NURSE statements and videos demonstrating their use can be found on the VitalTalk website [18].

3.2. Advance care planning

The objective of advance care planning (ACP) continues to be assisting patients in receiving goal-concordant care. Patients with cancer should not be pressured into forgoing aggressive treatment for COVID-19 infection; rather, gynecologic oncologists should help patients to formulate an advance care plan that reflects their choices while they are able to communicate those wishes. Fostering prognostic awareness is critical to these conversations, both related to COVID-19 infection and the underlying cancer. A patient may prefer to allow intubation for COVID-19 if she knows that her cancer is likely cured; a patient whose cancer-specific prognosis is measured in months may have different preferences. ACP must be informed by available data regarding clinical outcomes for patients with cancer who become symptomatic with COVID-19. For example, patients with cancer currently appear to be at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 [21], and may subsequently be more likely to incur severe morbidity including ICU admission, requirement for ventilator support, or death [22]. Further, risk of severe morbidity appears highest when the last cancer treatment was within the past 14 days [23]. Oncologists should ensure that prognostic data used in ACP is up to date, and appropriately qualified.

Gynecologic oncologists should strive to include ACP routinely in clinical encounters; the need for ACP is even more urgent under pandemic conditions. Conversation-starting questions may include, “What do I value about my life? If I will die if I am not put in a medical coma and placed on a ventilator, do I want that life support? Do I want tubes feeding me so I can stay on the ventilator for weeks?” [24] The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine as well as the non-profit Center to Advance Palliative Care have created COVID-19-specific resources, including recommendations and example scripts for discussing ACP [[25], [26], [27]].

Patients should also be encouraged to designate a surrogate healthcare decision-maker, in the event they lose the ability to make decisions for themselves. This information should be available in the medical record. Some institutions may allow patients to designate a surrogate decision-maker remotely through the electronic medical record, allowing this important issue to be addressed during telehealth visits.

3.3. Shared decision-making

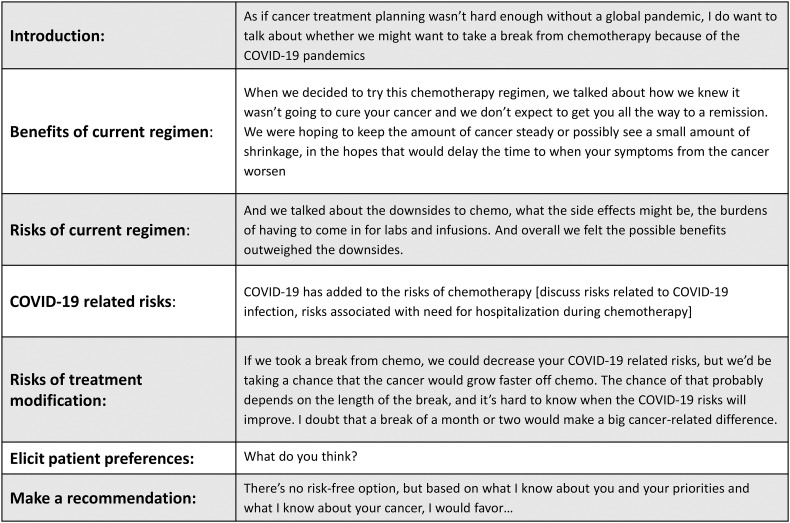

Under some circumstances, oncologists and patients may consider altering cancer treatment plans due to the COVID-19 pandemic [28]. Whenever possible, discussion of treatment modifications should take place within the framework of shared decision-making. Physicians should outline the rationale for standard cancer care (e.g., surgery or chemotherapy), explain how the COVID-19 pandemic may affect the ability of the healthcare system to deliver usual care, and the relative risks and benefits of the proposed alteration to the treatment plan. This conversation should finish with the physician making a recommendation. In some circumstances, patients may have the ability to decide whether to take on additional risk related to COVID-19 in order to continue cancer-directed therapy (e.g., maintenance use of an immunosuppressive medication). In other circumstances, both the patient and physician may have to adapt to usual care being unavailable (e.g., closure of operating rooms during hospital surge conditions). Fig. 2 outlines an example script of an approach to a conversation about possibly pausing disease-directed therapy because of COVID-19 for a patient with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer on chemotherapy, with moderate disease burden but relatively low symptom burden. Physicians should remain sensitive to the feelings of helplessness that may arise during these conversations, and attempt to empower patients as much as possible regarding their own care.

Fig. 2.

Example script for discussion of COVID-19 related treatment modification.

4. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted significant changes in the delivery of gynecologic cancer care. Gynecologic oncologists should be aware of the ethical underpinnings of these changes, and the general structure of crisis standards of care, including how scarce healthcare resources may be allocated. There is a continuing obligation to advocate for patients with gynecologic malignancies to receive the best care possible; treating physicians should ensure that patients are accurately represented in priority scores for scarce resources, and maximize the benefits of cancer-directed therapy while minimizing the risk of COVID-19 related morbidity. Gynecologic oncologists must also be aware of the ongoing need to provide palliative care during the pandemic, particularly through critical conversations, including the delivery of bad news, advance care planning, and shared treatment decision-making.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Spillman reports that for this manuscript, my role is the Chair of the SGO Professional Ethics Committee, the moderator of the SGO webinar on the topic and the senior author of the manuscript. My conflict disclosure is that I am also the Vice-Chair of the American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, but this manuscript does not represent policies of the AMA. The AMA CEJA position is a volunteer medical association leadership position.

All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Dr. Shalowitz reports serving as the current Chair of the Committee on Ethics for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the positions of ACOG.

Footnotes

On behalf of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. This SGO Clinical Practice Statement has been reviewed and approved by the SGO Clinical Practice Committee, Publication Committee and the Board of Directors. This SGO Clinical Practice Statement was not peer reviewed by Gynecologic Oncology.

References

- 1.Robinson S., Kissane D.W., Brooker J., Burney S. A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: a decade of research. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49(3):595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-gynecologists, Ethics. 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for-ob-gyns-ethics

- 4.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(21) doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crisis Standards of Care. National Academies Press; 2012. doi:10.17226/13351

- 6.White D.B., Lo B. A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the Covid-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5046. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent J.L., De Mendonça A., Cantraine F. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Crit. Care Med. 1998;26(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laventhal N., Basak R., Dell M.L. The ethics of creating a resource allocation strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1243. Published online May 4, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ethics Subcommittee of the Advisory Committee to the Director, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ethical Considerations for Decision Making Regarding Allocation of Mechanical Ventilators during a Severe Influenza Pandemic or Other Public Health Emergency. 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/od/science/integrity/phethics/docs/Vent_Document_Final_Version.pdf (Accessed May 24, 2020)

- 10.Society of Gynecologic Oncology Promoting Health Equity in the COVID-19 Era. 2020. https://www.sgo.org/clinical-practice/management/covid-19-resources-for-health-care-practitioners/promoting-health-equity-in-the-covid-19-era/ (Accessed May 31, 2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Federal Emergency Management Agency Incident Command System Resources. 2018. https://www.fema.gov/incident-command-system-resources (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 12.Federal Emergency Management Agency Incident Command System Review Document. 2018. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/is/icsresource/assets/ics.review.document.pdf (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 13.Utah Department of Health Utah Pandemic Influenza Hospital and ICU Triage Guidelines. 2009. http://pandemicflu.utah.gov/plan/med_triage081109.pdf (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 14.University of Pittsburgh Department of Critical Care Medicine A Model Hospital Policy for Allocating Scarce Critical Care Resources. 2020. https://www.ccm.pitt.edu/?q=content/model-hospital-policy-allocating-scarce-critical-care-resources-available-online-now (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 15.Center to Advance Palliative Care capc.org (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 16.Littell R.D., Kumar A., Einstein M.H., Karam A., Bevis K. Advanced communication: a critical component of high quality gynecologic cancer care: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology evidence based review and guide. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019;155(1):161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quill T.E., Abernethy A.P. Generalist plus specialist palliative care - creating a more sustainable model. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368(13):1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.VitalTalk www.vitaltalk.org (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 19.Schwartz T., Pines E. Coping with fatigue, fear, and panic during a crisis. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020;3 https://hbr.org/2020/03/coping-with-fatigue-fear-and-panic-during-a-crisis [Google Scholar]

- 20.VitalTalk Responding to Emotion: Respecting. https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/responding-to-emotion-respecting/ (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 21.Yu J., Ouyang W., Chua M.L.K., Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. Published online 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. Published online 2020. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Dreger K. The New York Times; April 4, 2020. What You Should Know Before You Need a Ventilator.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/04/opinion/coronavirus-ventilators.html [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Published online 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.4894 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Center to Advance Palliative Care CAPC COVID-19 Response Resources. 2020. https://www.capc.org/toolkits/covid-19-response-resources/ (Accessed 5/24/2020)

- 27.American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Resources to Address Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. http://aahpm.org/education/covid-19-resources (Accessed 5/24/2020.

- 28.Schrag D, Hershman DL, Basch E. Oncology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Published online 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6236 [DOI] [PubMed]