Highlights

-

•

Terrific SARS experience and citizens’ distrust to government have remarkable impacts on COVID-19 in Hong Kong.

-

•

Self-discipline of citizens contributes to the low infection rate.

-

•

Districts with pro-democratic councilors are more proactive in community mobilization in anti-pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, civil society, social mobilization, Asia, Hong Kong

Abstract

The globalized world economy has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic since early February 2020. In the midst of this global public health crisis, a prompt review of the counterinsurgencies that have occurred in different jurisdictions is helpful. This article examines the experience of Hong Kong (HKSAR), which successfully limited its number of confirmed cases to approximately 1100 until early June 2020. Considering the limited actions that the government has taken against the pandemic, we emphasize the prominent role of Hong Kong’s civil society through highlighting the strong and spontaneous mobilization of its local communities originating from their experiences during the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the social unrest in 2019, as well as their doubts regarding the pandemic assessments and recommendations of the HKSAR and WHO authorities. This article suggests that the influence of civil society should not be overlooked in the context of pandemic management.

1. Introduction

Conventional wisdom acknowledges the crucial role of the state in sustaining health services and reducing the risk of epidemics (Dionne, 2011, Lieberman, 2007, Bollyky et al., 2019, Wigley and Akkoyunlu-Wigley, 2011). Most governments view regional lockdowns, social distancing and massive screening as rational responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and some state-centric approaches provide a model for the rest of the world (Wang, Ng, & Brook, 2000). However, it is worth studying the roles of public personnel in the COVID-19 situation and the ways in which society responds to this pandemic. In this article, we examine the experience of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) to explain the importance of civil society and social mobilization as decisive elements of the fight against the pandemic.

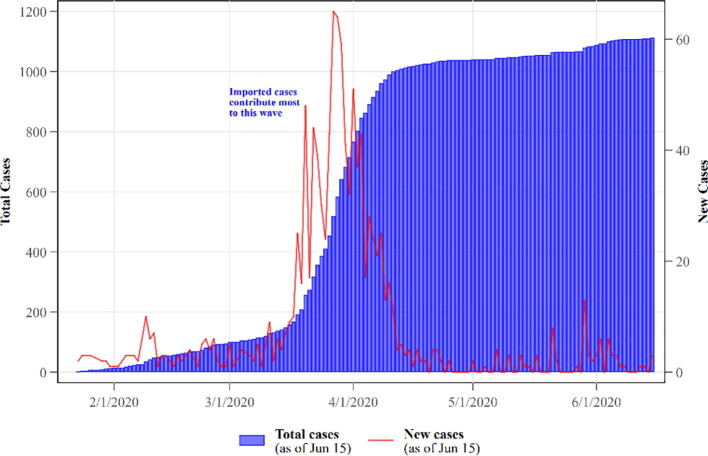

In the time between the outbreak of COVID-19 in mainland China during the month of January to mid-June, there have been approximately 1100 confirmed cases of the virus in Hong Kong, which is densely populated with over 8 million people (Fig. 1 ). In addition to the government’s efforts to limit the spread of the virus,1 the role of civil society is prominent to combat the surge of infection. Paradoxically, the strong and spontaneous mobilization observed in Hong Kong was a consequence of the population’s devastating memories of the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the social unrest in 2019, as well as of their skepticism of the pandemic figures, assessments and recommendations given by the authorities of HKSAR, mainland China, and the World Health Organization (WHO). The lesson that can be learned from Hong Kong is that of an alternative approach to ensuring the effectiveness of pandemic management.

Fig. 1.

Confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Hong Kong (as of June 15, 2020).

2. Community response: anxiety, distrust and social mobilization

2.1. Anxiety: lesson from SARS 2003

The advent of COVID-19 (also known as SARS-CoV-2) reminded the public of their experience during the SARS outbreak in 2003, which led to 1755 cases and 299 deaths as well as economic depression in Hong Kong. As a result of this experience, the public learned the importance of social distancing, personal hygiene, and the use of surgical masks in the context of SARS-like pandemics (Lau, Griffiths, Choi, & Tsui, 2010). Among their Asian neighbors, Hong Kong citizens were the first to react to the pandemic. Using Apple mobility trend data, Fig. 2 shows that Hong Kong citizens rapidly reduced their frequency of walking out of their homes by over 40% (from 100 to approximately 50) after the first reported case in Hong Kong on Jan 23.2 This trend continued even during the Lunar New Year public holiday occurring days after.3

Fig. 2.

Mobility trends during the COVID-19 period. Source: Apple, 2020.

In addition to social distancing, Hong Kong citizens began using surgical masks at the beginning of the pandemic, even when it was not recommended by the WHO officers. Approximately 74.5% of the adults in Hong Kong used surgical masks in public areas in late January, and 95% of the people used surgical masks in February and March (Cowling, Ali, Ng, Tsang, Li, Fong, & Wu, 2020); this proved to be an effective in limiting the spread of COVID-19 (Cheng et al., 2020, Chan et al., 2020). The experience of devastation of the SARS outbreak in 2003 led to Hong Kong society being self-disciplined and experienced in its fight against COVID-19, which prevented a large-scale community outbreak during the early stages of this pandemic.

2.2. Distrust: legacies of the anti-extradition bill movement

Extant works have suggested the crucial role of the state in the context of a pandemic; however, its effectiveness is dependent on the public’s perception of the legitimacy of the government (Wallner, 2008, Gibson et al., 2005). Initially, the public demand for preventive measures from the government was high, and these measures included a full closure of the border between Hong Kong and Mainland China and a sustainable supply of surgical masks. However, the HKSAR government was reluctant to act proactively and thus exacerbated the tension and distrust that had already been deeply established during the Anti-Extradition Bill movement of 2019.

Fig. 3 shows that over 70% of the public was dissatisfied with the government’s performance in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic before March, which was a crucial period for the containment of the pandemic. Simultaneously, a media-conducted survey suggested that most respondents believed that Hong Kong citizens should be credited for the success achieved regarding the containment of the pandemic instead of the government (Cheung & Wong, 2020).

Fig. 3.

Attitudes regarding the HKSAR government’s performance in addressing coronavirus disease. .

Source: Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. (2020a), 2020a

Indeed, the prominent dissatisfaction of Hong Kong citizens is accompanied by declining trust towards the government. In Fig. 4 , we can observe a dramatic decline in the government trust from June 2019, when the Anti-extradition Bill movement began. In the early stages of the pandemic (January to March), the rate of support for the Chief Executive was also recorded below 20 over 100, and less than 30% of the population trusted the government and were satisfied with the police force (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020d, Ho, 2020). It was argued that this attitude towards the police force has become a major divide between the citizens of Hong Kong and the HKSAR government (Chau & Wan, 2020). These attitudes have led to considerable public doubts about the measures that the government has taken and the policies that it has implemented in response to COVID-19. For instance, the Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance, which prohibits all public gatherings of more than eight people, is perceived as a double standard, as police officers cited the ordinance for crowd control purposes in March4 but the government permitted the reopening of amusement parks and the Hong Kong Book Fair 2020 in June.

Fig. 4.

Attitudes towards and trust of the HKSAR government, the Chief executive, and the police force. .

Source: Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020b, Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020c, Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020d

2.3. Social mobilization: community network and self-help model

The HKSAR government’s reluctance to fully shut down its border and the deeply rooted distrust between society and the government have raised questions regarding the rationale and priorities behind the government’s policy-making process. Some believe that the government has placed national interest and pride over public safety and local interest, which resulted in the following actions and responses from society. A community-based mobilization of mutual assistance was implemented instead of full reliance on governmental actions.

The most salient case is the sharing and distribution of community-based personal protective equipment (PPE), particularly surgical masks and hand sanitizers.

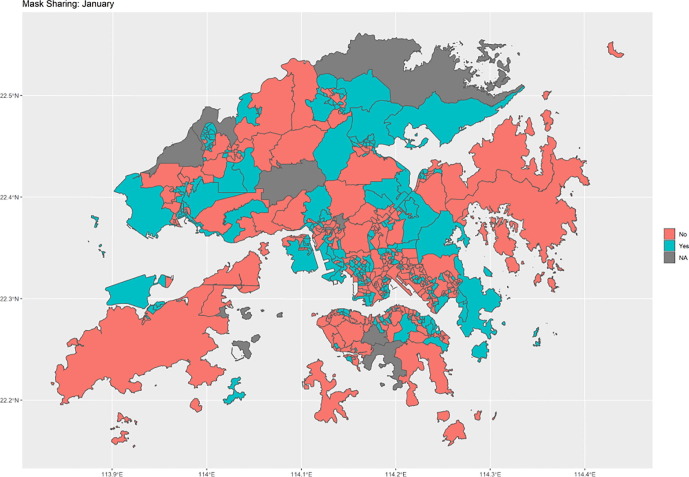

The supply of surgical masks was limited due to the export bans implemented by other countries and the public’s considerable demand as influenced by their experience during the SARS outbreak. While the WHO officers insisted that it was not recommended for healthy individuals to use surgical masks, the Chief Executive refused to respond to the public demand for surgical masks and mandated that government officials and civil servants take off their surgical masks at work. The supply of surgical masks (both purchased and donated) in Hong Kong was sustained by the efforts of the District Councilors, local organizations and shop owners through mask sharing events. Fig. 5, Fig. 6 shows the mask distribution densities of 432 district councilors from January to early February.5 Over 40% of the District Councilors held at least one sharing activity in January, and this number increased to 65% and 82% in early and late February, respectively. These mask distributions were prioritized to serve the disadvantaged and groups with a high level of exposure risk6 , as these groups are the most vulnerable to COVID-19 (Jordan, Adab, & Cheng, 2020).

Fig. 5.

Mask sharing in Hong Kong (January).

Fig. 6.

Mask sharing in Hong Kong (February: first half).

It is argued that the pro-democratic councilors, as a proxy representing a higher level of government distrust, were the first to act. Fig. 7 shows that the density of mask sharing in these pro-democratic districts is considerably higher than that of the pro-Beijing districts before March.7 This implies that the higher the distrust towards the government is in a district, the faster the response of this district was.

Fig. 7.

The density of mask sharing frequency of the pro-democratic and pro-Beijing districts.

In addition to PPE sharing, this distrust of the government also led to more progressive actions against government measures. In late January, the Hospital Authority Employees Alliance (HKEA), a union formed by medical professionals, organized a strike to demand a complete border shutdown after the Chief Executive refused to shut down the high-speed railway to China and restricted incoming travelers from Wubei. Over 60% of the public consistently supported this strike, and the government eventually announced that it would be partially shutting down the high-speed railway to China in early February (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020a). Thus, the strike of HKEA prevented a potential large-scale outbreak caused by travelers from infected regions.

Furthermore, the public distrust and social unrest occurring since the summer of 2019 have reshaped the public communications in Hong Kong. As the public remained doubtful of the official figures and advice from the HKSAR government, China and the WHO,8 citizens accessed social media such as Facebook, YouTube channels, and public or private Telegram groups to exchange the latest COVID-related news, reports and information; this was also a common practice during the Anti-Extradition Bill movement (Lee, Yuen, Tang, & Cheng, 2019). Users of these channels were reminded to check residential pipes and drainage systems, prompted to verify facts, shown how to test unqualified PPE, and taught how to make cloth masks and hand sanitizers at home. A real-time dashboard, which included details regarding the cases, high-risk areas, questionable pharmacies, etc.9 , was established far before the government official dashboard was established. These platforms provided public-friendly access to COVID-19-related information; this was essential in the fight against COVID-19, since unequal access to information due to differences in socioeconomic status would impede the effectiveness of the society’s response to this public health crisis (Lin, Jung, McCloud, & Viswanath, 2014).

A social and community-based network formed by these self-help models has promoted the protection of the public, especially that of disadvantaged groups and high-risk workers. The fast and transparent circulation of information has enabled citizens to overcome the collective challenges that have faced them (Putnam, 1993).

3. Conclusion

An important discussion regarding successful pandemic management centers on governance capacity, including information transparency and timely responses to potential threats. Taiwan and Hong Kong are identified as outstanding cases regarding the containment of the deadly COVID-19 virus due to the low number of confirmed cases and deaths in these places. While Taiwan’s success was identified as a model of high governance capacity, this article presented Hong Kong’s success as a case supported by civic society and social mobilization.

Existing studies have suggested that trust between society and the government is crucial in responding to epidemics (Blair, Morse, & Tsai, 2017), and it is possible that the public gained a higher approval of leadership and a higher sense of national unity during this crisis, as the “rally-round the flag” concept suggested (Mueller, 1970, Baum, 2002). In this article, we demonstrated that public distrust of the government may not necessarily lead to a failure of pandemic control. In contrast, skepticism of ineffective policies and the presence of a strong civic society driven by state society tensions may contribute positively to pandemic management. The case of Hong Kong exhibits a sharp deviation from the mainstream discourse that places a dual emphasis on capacity and accountability in effective crisis management.

However, it should be made clear that our findings should not be interpreted to undermine the important role of the state in pandemic management. We are rather suggesting that the influence of civil society should be taken into serious consideration in the context of public health crisis-related studies (Eimer & Lütz, 2010).

Conflict of interest

We declare there is no conflict of interest among the authors and their funding bodies in the preparation of this manuscripts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kin-Man Wan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Writing - original draft. Lawrence Ka-ki Ho: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Natalie W.M. Wong: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Andy Chiu: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgement

Wan thanks Tak-Huen Chau for the valuable comments and support.

Footnotes

For details regarding the measures taken by the HKSAR government, please refer to Appendix A.

A survey also found that approximately 61.3% respondents avoiding going to crowded places (Cowling et al., 2020), which is highly consistent with the Apple mobility trend data.

Driving data from Apple also exhibits a similar trend as does the walking data. For these similar results using data drawn from the Google community mobility report, please see Appendix B.

This gathering is a monthly event held to commemorate the protesters and commuters who were injured in a confrontation with riot police at a metro station. Over half (55%) of the people of Hong Kong believe that the social distancing rule is a means for political suppression rather than for fighting against the pandemic (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020a).

The graph shows each reported event’s frequency. We developed a novel dataset by collecting data from each district councilors’ Facebook fan page or personal public account. We excluded all institutional-supported resources and events. For the coding rules and data details, please see Appendix C. We only consider the density of mask sharing rather than including all PPE sharing, because the demand for masks was contradictory to the government’s advice; thus, this factor can better to show the how distrust determines people’s behavior, and thus reduces transmission.

For instance, lower socioeconomic status groups, elderly people, patients with chronic illnesses, medical workers, building security guards, and cleaning workers.

The pro-Beijing councilors are much more resourceful than the pro-democratic (Wong, 2015). We also provide more supportive evidence and placebo test in appendix, please refer to Tables A2–A5, and Fig. A10.

Over 55% respondents dissatisfied with WHO works on the COVID-19 (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020a).

Please visit COVID-19 in HK https://wars.vote4.hk/en.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105055.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Apple. (2020). Apple Mobility Trends Reports. https://www.apple.com/covid19/mobility.

- Baum M.A. The constituent foundations of the rally-round-the-flag phenomenon. International Studies Quarterly. 2002;46(2):263–298. [Google Scholar]

- Blair R.A., Morse B.S., Tsai L.L. Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in Liberia. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;172:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollyky T.J., Templin T., Cohen M., Schoder D., Dieleman J.L., Wigley S. The relationships between democratic experience, adult health, and cause-specific mortality in 170 countries between 1980 and 2016: An observational analysis. The Lancet. 2019;393(10181):1628–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30235-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.W., Yuan S., Zhang A.J., Poon V.K.M., Chan C.C.S., Lee A.C.Y.…Tang K. Surgical mask partition reduces the risk of non-contact transmission in a golden Syrian hamster model for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau, T. H., & Wan, K. M. (2020). Pour (tear) gas on fire? Violent confrontations and anti-government backlash in Hong Kong. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3557130.

- Cheng V.C., Wong S.C., Chuang V.W., So S.Y., Chen J.H., Sridhar S.…Yuen K.Y. The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, T., & Wong, N. (2020). Most Hongkongers unhappy with official Covid-19 response, Post poll shows. Retrieved June 09, 2020, from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3077761/coronavirus-post-poll-shows-hong-kong-residents-unhappy.

- Cowling B.J., Ali S.T., Ng T.W., Tsang T.K., Li J.C., Fong M.W.…Wu J.T. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: An observational study. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e297–288. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne K.Y. The role of executive time horizons in state response to AIDS in Africa. Comparative Political Studies. 2011;44(1):55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Eimer T., Lütz S. Developmental states, civil society, and public health: Patent regulation for HIV/AIDS pharmaceuticals in India and Brazil. Regulation & Governance. 2010;4(2):135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J.L., Caldeira G.A., Spence L.K. Why do people accept public policies they oppose? Testing legitimacy theory with a survey-based experiment. Political Research Quarterly. 2005;58(2):187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ho L.K.K. Legitimization & De-legitimization of Police. In British Colonial & Chinese SAR Hong Kong. Journal of Inter-Regional Studies: Regional and Global Perspectives. 2020;3:2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. (2020a). “Community health module” research report (Chinese only). https://www.pori.hk/research-reports.

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. (2020b). Popularity of Chief Executive. https://www.pori.hk/pop-poll/chief-executive/a003/rating.

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. (2020c). People’s trust in the HKSAR government. https://www.pori.hk/pop-poll/hksarg/k001.

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. (2020d). People’s satisfaction with the disciplinary force- Hong Kong Police Force. https://www.pori.hk/pop-poll/disciplinary-force/x001/satisfaction.

- Jordan, R. E., Adab, P., & Cheng, K. K. (2020). Covid-19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lau J.T., Griffiths S., Choi K.C., Tsui H.Y.n. Avoidance behaviors and negative psychological responses in the general populatiostage of the H1N1 pandemic in Hong Kong. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10(1):139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee F.L., Yuen S., Tang G., Cheng E.W. Hong Kong’s summer of uprising. China Review. 2019;19(4):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman E.S. Ethnic politics, risk, and policy-making: A cross-national statistical analysis of government responses to HIV/AIDS. Comparative Political Studies. 2007;40(12):1407–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Jung M., McCloud R.F., Viswanath K. Media use and communication inequalities in a public health emergency: A case study of 2009–2010 pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1. Public Health Reports. 2014;129(6_Suppl4):49–60. doi: 10.1177/00333549141296S408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J.E. Presidential popularity from Truman to Johnson. American Political Science Review. 1970;64(1):18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1993. Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Wallner J. Legitimacy and public policy: Seeing beyond effectiveness, efficiency, and performance. Policy Studies Journal. 2008;36(3):421–443. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.J., Ng C.Y., Brook R.H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1341–1342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigley S., Akkoyunlu-Wigley A. The impact of regime type on health: Does redistribution explain everything? World Politics. 2011;63(4):647–677. doi: 10.1017/s0043887111000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.H.W. Springer; Singapore: 2015. Electoral politics in post-1997 Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.