Dear Editor,

We read with great interest the recent study by Azzi et al.1 who reported that saliva was a reliable tool to detect severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and further confirmed by Iwasaki et al.2 that saliva was a noninvasive alternative to nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs. To have a better evaluation of the clinical usefulness and viral RNA shedding pattern in saliva specimens, in this letter, we further evaluated the clinical performance of saliva in comparison with paired respiratory tract specimens in a larger cohort of patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), and analyzed the temporal change in viral loads and its correlation with severity of illness in saliva.

An outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 that began in Wuhan, Hubei Province of China, has rapidly developed into a global pandemic. As of June 19, 2020, a total of 8385,440 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases and 450,686 deaths have been reported worldwide. Early, rapid and accurate diagnosis is of vital importance in forestalling the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

At present, the “gold” standard to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection is by real-time reverse-transcription–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) in respiratory tract specimens, mainly nasopharyngeal (NP) and oropharyngeal (OP) swabs. However, the collection of these specimens is a relatively invasive procedure, which causes severe discomfort. In particular, the close contact involved in swab collection might put healthcare workers at higher risk for viral transmission.

Saliva specimens, in contrast, can be easily self-collected by patients. Findings of previous studies have demonstrated successful detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in saliva, proving it as an appealing noninvasive alternative to NP or OP swabs for the diagnosis and viral load monitoring of SARS-CoV-2.1, 2, 3 However, the clinical usefulness of saliva specimens for diagnosing COVID-19 has yet to be thoroughly evaluated due to the small sample size. Besides, the viral load dynamics in saliva samples and the relationship between viral load and disease severity are also unknown. Here, we compared the detection sensitivity of paired respiratory tract and saliva specimens in diagnosing COVID-19, and described the temporal profile of viral loads in patients with mild and severe COVID-19 in saliva.

In total, 944 patients from 12 independent cohorts were included (Table S1). To determine the diagnostic performance of real-time RT-PCR in saliva, the RT-PCR results from respiratory tract samples were used as reference. Among them, 442 cases were confirmed with SARS-CoV-2 infection by real-time RT-PCR in respiratory tract specimens (Table 1 ). Of these, 382 patients were SARS-CoV-2 positive in both saliva and respiratory tract specimens, and 60 patients tested positive only in respiratory tract samples. In 502 patients whose respiratory tract specimens tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, 15 saliva specimens had viral RNA detectable. When compared to the respiratory tract samples, the sensitivity and specificity of saliva were 86.4% (95% CI 82.8%−89.4%) and 97.0% (95% CI 95.0%−98.3%), respectively. Analysis of the concordance revealed a 92.1% observed virus detection accuracy and a firm agreement of diagnosis between the respiratory tract and saliva sample (Kohen's kappa coefficient 0.840, 95% CI 0.805–0.874).

Table 1.

The comparison for the real-time RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 between respiratory tract and saliva sample.

| Saliva | Respiratory tract sample |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 382 | 15 | 397 |

| Negative | 60 | 487 | 547 |

| Total | 442 | 502 | 944 |

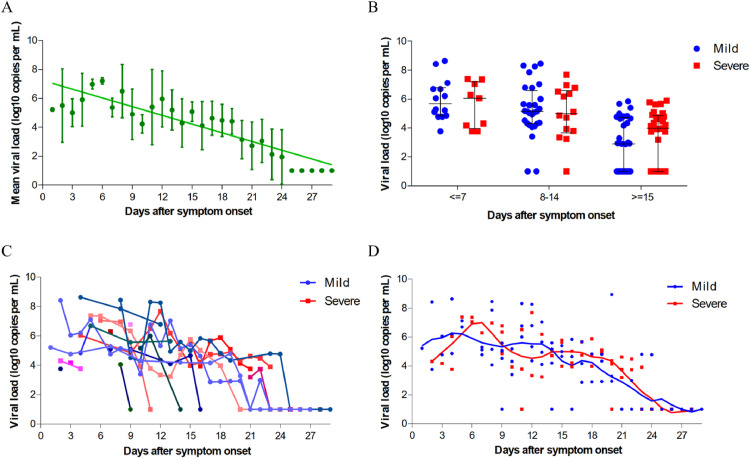

In addition, with the aim to illustrate the viral RNA shedding pattern in saliva and predict its correlation with illness severity in patients with COVID-19, 126 saliva specimens were serially collected from 20 patients, with 11 (55%) individuals classified as mild cases and 9 (45%) classified as severe cases. Our data indicated that the SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels in saliva peaked soon in one week after symptom onset, ranging from around 10⁴ to 108 copies per mL during this time, then steadily declined (Fig. 1 A). 40% (8/20) patients had a viral shedding period longer than 14 days in saliva. The prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in saliva samples was not associated with disease severity (p = 0.535). We further analyzed the correlation between viral loads in saliva and severity of illness according to the day after disease onset at the time of sampling. The mean viral load of severe cases showed no significant difference from those of corresponding mild cases for all the indicated period (Fig. 1B). The viral RNA clearance patterns in saliva samples were also observed similarly in mild and severe COVID-19 patients (Fig. 1C, D).

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 viral load in saliva from patients with COVID-19. (A) Viral load from serial saliva samples. Mean and standard deviation are shown. (B) Viral load from patients with mild and severe COVID-19 at different stages of disease onset. Median, quartile 1, and quartile 3 are shown. (C) Viral load of serial samples from patients with mild and severe COVID-19. (D) Viral load from patients with mild and severe COVID-19. The line represents smooth curve of best fit.

In this study, we proved saliva as an acceptable noninvasive alternative source for the diagnosis and viral load monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in a large cohort of patients. Saliva exhibited comparable sensitivity and strong agreement to the current COVID-19 diagnosis standard by using respiratory tract specimens. Of interest, saliva tested positive in 15 patients from whom respiratory tract specimens were negative for SARS-Cov-2, raising the contagious possibility through their saliva even when swabs are negative. Moreover, collecting specimens with saliva has several advantages over NP and OP swabs. The process of collecting saliva is noninvasive and can be reliably self-administered, reducing the exposure and virus transmission risk to healthcare workers, and decreasing supply demands on swabs and personal protective equipment.

Higher salivary viral loads were detected soon after symptom onset and subsequently declined with time in our cohort study. It was consistent with previous findings in throat swab and sputum samples,4 as well as in saliva samples.5 Viral loads in saliva were comparable to those in sputum and throat swabs as well,4 varying from about 10⁴ to 108 copies per mL during the first week of symptoms. The RNA shedding pattern was distinct from that in patients infected with SARS-CoV, which typically peaked at around ten days after onset of illness.6 The high viral load on presentation suggested that early antiviral treatment might benefit the recovery for patients with COVID-19. A similar viral RNA shedding pattern in saliva was observed in mild and severe COVID-19 patients, but differed from what presented in NP swabs.7 It might be due to the prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in saliva samples, while NP swabs became negative over time.8 , 9

In summary, our study showed that saliva might serve as a promising substitutable choice to the current COVID-19 diagnosis standard by using respiratory tract specimens with comparable performance. Salivary viral load peaked during the first week of symptoms and gradually declined over time. Surprisingly, there was no significant difference regarding the temporal viral load profile between mild and severe cases in our study. Further investigation in a larger cohort is warranted to reveal the correlation between salivary viral loads and disease severity.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board and informed consent was obtained from all patients

Funding

This work was supported by Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Program (No. 2019B030301009), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2019M653046) and National Natural Science Foundation (No. 31800064).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kelvin Kparai-Wang To (The University of Hong Kong) for providing some viral load data.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.059.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Azzi L., Carcano G., Gianfagna F., Grossi P., Gasperina D.D., Genoni A. Saliva is a reliable tool to detect SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. Jul 2020;81(1):e45–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.005. PubMed PMID: 32298676. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7194805. Epub 2020/04/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki S., Fujisawa S., Nakakubo S., Kamada K., Yamashita Y., Fukumoto T. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 detection in nasopharyngeal swab and saliva. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.071. Jun 4PubMed PMID: 32504740. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7270800 interests. Epub 2020/06/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.To K.K., Tsang O.T., Chik-Yan Yip C., Chan K.H., Wu T.C., Chan J.M.C. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of AmericaFeb 12. PubMed PMID: 32047895. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7108139. Epub 2020/02/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Y., Zhang D., Yang P., Poon L.L.M., Wang Q. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. AprPubMed PMID: 32105638. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7128099. Epub 2020/02/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.To K.K., Tsang O.T., Leung W.S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. MayPubMed PMID: 32213337. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7158907. Epub 2020/03/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peiris J.S., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Chan K.S., Hung I.F., Poon L.L. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. May 24PubMed PMID: 12781535. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7112410. Epub 2003/06/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y., Yan L.M., Wan L., Xiang T.X., Le A., Liu J.M. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):656–657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. JunPubMed PMID: 32199493. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7158902. Epub 2020/03/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzi L., Carcano G., Dalla Gasperina D., Sessa F., Maurino V., Baj A. Two cases of COVID-19 with positive salivary and negative pharyngeal or respiratory swabs at hospital discharge: a rising concern. Oral Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/odi.13368. Apr 25. PubMed PMID: 32333518. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7267504. Epub 2020/04/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller M., Jansen M., Bisignano A., Mahoney S., Wechsberg C., Albanese N. Validation of a Self-administrable, Saliva-based RT-qPCR Test Detecting SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. 2020 2020.06.05.20122721. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.