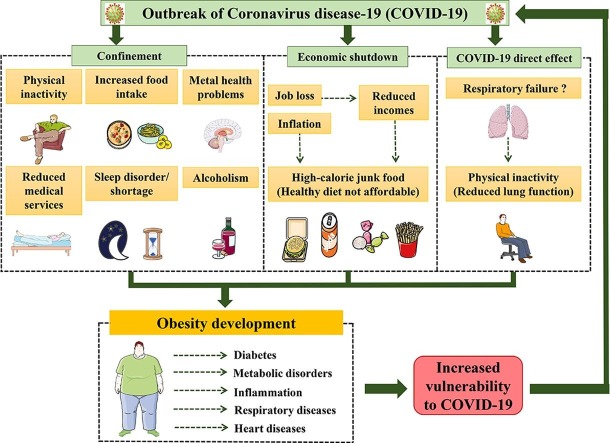

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), Obesity

Dear editors,

With the current outbreak of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) [1] , debates are taking place around the consequences this pandemic would have on different aspects of the human health including obesity. This virus has the ability to spread in a way, so far, too fast to be easily controlled. Thus, in order to avoid the overload of the health system, many governments and public health authorities worldwide have imposed (among other implemented measures) home confinement and general lockdown that lead to a variety of consequences. Among these consequences, we put a spotlight on those well-known to be related to obesity epidemiology through selected illustrations.

During this critical period of COVID-19 pandemic, the mental health is among what health professionals are most concerned about. Mental health complications including depression, anxiety, stress, and diverse psychological problems can result from isolation and reduced social activities, human connection and physical interaction [2], [3], [4] due to home confinement, closed parks and gymnasiums, etc. Such mental problems can also result from, lead to or be associated with disturbed sleeping cycle and sleep shortage (that can also result from home confinement [5]) and vice versa [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Both psychological status and sleeping disorders could lead to increased food intake and obesity risk [13], [14]. In addition, mental health and sleep disorders may require prescribing medicines that impact the energy balance and increase weight [15], which would further contribute the development of obesity. Indeed, obesity is basically defined as resulting from an increased energy intake compared to the energy expenditure, the physical activity and the food intake are two important pillars in obesity-related energy balance [13]. Within this context, home confinement combined to the related mental problems (like anxiety and depression) would lead to increased food intake, especially that many individuals have important food storages at home cumulated prior and during the lockdown. Following the same logic, confinement and its impact on mood could incite to higher alcohol consumption which can further contribute to weigh gain [16], [17]. For the energy expenditure part, the home confinement (absence of work out equipment) and the disturbed mental health (lack of sufficient motivation) would lead to a physical inactivity (sedentary lifestyle). Therefore, these result in an energy balance towards an obesity establishment.

Within the context of diet choice, the socioeconomic crisis expected to develop during and after the current COVID-19 crisis [18], [19] would lead to inflation of different products prices. Therefore, less individuals will afford to buy healthy food (expensive) especially knowing that millions lost their jobs and have seen their incomes significantly decreased. Therefore, the consumption of junk food (unhealthy and with a high caloric density), which is more affordable, more available and easy to store, will increase and lead to increased risk of obesity among other health problems [20]. Moreover, patients who get the respiratory illness of COVID-19 might have reduced lung function [21], [22] (possibly even after they recover), which would limit their ability to perform physical activity due to the respiratory failure. These would further switch the energy balance towards developing obesity following the decrease of physical activity-related energy expenditure.

Importantly, individuals avoiding public places or keeping away from health care facilities (to protect themselves from contracting COVID-19), via limiting the number of times they leave home, may neglect seeking medical assistance to take care of their health problems for which they would have visited health professionals under normal circumstances. Furthermore, individuals that have had their incomes reduced may not be able to afford medical services (especially those not covered by insurances). Finally, the saturation of health systems because of COVID-19 made that numerous medical services (mostly non urgent) have been suspended is certain health care facilities. All these elements will reduce the quality of health care that populations receive and would worsen the pre-existing health conditions towards more serious diseases. These are additional factors strengthening the establishment and the persistence of obesity, diabetes and divers other metabolic disorders and chronic diseases in our societies.

Herein, we have illustrated how selected COVID-19 pandemic-related concepts do increase obesity risk and therefore multiple obesity-related morbidities including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, etc [23]. Obesity and those morbidities resulting from measures implemented to prevent COVID-19 spread and limit its mortality would, ironically, make the individuals more vulnerable to COVID-19 [24]. Importantly, it is of an extreme importance to make sure we do not replace COVID-19 pandemic with another pandemic(s) such as obesity which is already epidemic [25]. This can be achieved by implementing a variety of complimentary approaches to compensate the lost healthy practices and habits of the daily life. This could be reached, for instance, via the use of online tools to organise social activities, medical appointments, psychotherapies along with economic measures to reduce the heavy socioeconomic impacts on individuals as well.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

Abdelaziz Ghanemi is a recipient of a Merit scholarship program for foreign students from the Ministry of Education and Higher Education of Quebec, Canada, The Fonds de recherche du Québec–Nature et technologies (FRQNT) is responsible for managing the program (Bourses d’excellence pour étudiants étrangers du Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement supérieur du Québec, Le Fonds de recherche du Québec–Nature et technologies (FRQNT) est responsable de la gestion du programme). The graphical abstract was created using images from: http://smart.servier.com. Servier Medical Art by Servier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License and Scidraw.io (Image’s author: John Chilton).

Authors’ contribution

Abdelaziz Ghanemi designed the manuscript structure and wrote it. Abdelaziz Ghanemi, Mayumi Yoshioka and Jonny St-Amand discussed the content and exchanged ideas and suggestions (concepts to add, the graphical abstract, references selection, etc) throughout the writing process and edited (and critically revised) the review. Jonny St-Amand gave the final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests. This paper does not take any position neither for nor against any decision of a political or an economic nature.

References

- 1.Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O'Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int J Surgery (London, England). 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagerty S.L., Williams L.M. The impact of COVID-19 on mental health: the interactive roles of brain biotypes and human connection. Brain Behav Immun – Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover S., Dua D., Sahoo S., Mehra A., Nehra R., Chakrabarti S. Why all COVID-19 Hospitals should have Mental Health Professionals: the importance of mental health in a worldwide crisis! Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;102147 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altena E., Baglioni C., Espie C.A., Ellis J., Gavriloff D., Holzinger B. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. J Sleep Res. 2020: doi: 10.1111/jsr.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.João K., Jesus S.N., Carmo C., Pinto P. The impact of sleep quality on the mental health of a non-clinical population. Sleep Med. 2018;46:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone K.L., Xiao Q. Impact of poor sleep on physical and mental health in older women. Sleep Med Clinics. 2018;13(3):457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorsteinsson E.B., Brown R.F., Owens M.T. Modeling the effects of stress, anxiety, and depression on rumination, sleep, and fatigue in a nonclinical sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(5):355–359. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalmbach D.A., Anderson J.R., Drake C.L. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. J Sleep Res. 2018;27(6) doi: 10.1111/jsr.12710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St-Onge M.P. Sleep-obesity relation: underlying mechanisms and consequences for treatment. Obesity Rev. 2017;18(Suppl 1):34–39. doi: 10.1111/obr.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayon V., Leger D., Gomez-Merino D., Vecchierini M.F., Chennaoui M. Sleep debt and obesity. Ann Med. 2014;46(5):264–272. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.931103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan W.S., Levsen M.P., McCrae C.S. A meta-analysis of associations between obesity and insomnia diagnosis and symptoms. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghanemi A., Yoshioka M., St-Amand J. Broken energy homeostasis and obesity pathogenesis: the surrounding concepts. J Clin Med. 2018;7(11) doi: 10.3390/jcm7110453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atlantis E., Goldney R.D., Wittert G.A. Obesity and depression or anxiety. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gafoor R., Booth H.P., Gulliford M.C. Antidepressant utilisation and incidence of weight gain during 10 years' follow-up: population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2018;361 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traversy G., Chaput J.P. Alcohol consumption and obesity: an update. Current Obesity Rep. 2015;4(1):122–130. doi: 10.1007/s13679-014-0129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayon-Orea C., Martinez-Gonzalez M.A., Bes-Rastrollo M. Alcohol consumption and body weight: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(8):419–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharif A., Aloui C., Yarovaya L. COVID-19 pandemic, oil prices, stock market, geopolitical risk and policy uncertainty nexus in the US economy: fresh evidence from the wavelet-based approach. Int Rev Financ Anal. 2020;70 doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shammi M., Bodrud-Doza M., Towfiqul Islam A.R.M., Rahman M.M. COVID-19 pandemic, socioeconomic crisis and human stress in resource-limited settings: a case from Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2020;6(5) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Payab M., Kelishadi R., Qorbani M., Motlagh M.E., Ranjbar S.H., Ardalan G. Association of junk food consumption with high blood pressure and obesity in Iranian children and adolescents: the Caspian-IV Study. Jornal de Pediatria (Versão em Português) 2015;91(2):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartman M.E., Hernandez R.A., Patel K., Wagner T.E., Trinh T., Lipke A.B. COVID-19 respiratory failure: targeting inflammation on VV-ECMO support. ASAIO J (American Society for Artificial Internal Organs: 1992) 2020 doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghanemi A., St-Amand J. Redefining obesity toward classifying as a disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;55:20–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchis-Gomar F., Lavie C.J., Mehra M.R., Henry B.M., Lippi G. Obesity and outcomes in COVID-19: when an epidemic and pandemic collide. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bray G.A., Macdiarmid J. The epidemic of obesity. Western J Med. 2000;172(2):78–79. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]