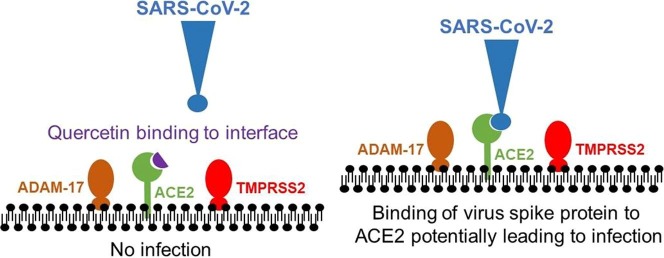

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme-2; ADAM-17, ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease, serine 2

Abstract

Commonly used drugs for treating many conditions are either natural products or derivatives. In silico modelling has identified several natural products including quercetin as potential highly effective disruptors of the initial infection process involving binding to the interface between the SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) Viral Spike Protein and the epithelial cell Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE2) protein. Here we argue that the oral route of administration of quercetin is unlikely to be effective in clinical trials owing to biotransformation during digestion, absorption and metabolism, but suggest that agents could be administered directly by alternative routes such as a nasal or throat spray.

1. Introduction

The first disease-initiating interaction of the SARS-CoV-2 virus with the human organism at the molecular level is through binding of the Viral Spike Protein with ACE2 (angiotensin converting enzyme-2). ACE2 is an enzyme attached by a single tail to the outer cell membrane and is particularly highly expressed in the goblet and ciliated cells of the nasal cavity [1]. In silico modelling of the interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 Viral Spike Protein and ACE2 identified quercetin from a database of 8,000 small molecule candidates of known drugs, metabolites, and natural products as one of the top 5 most potent compounds for binding to the interface site and potentially disrupting the initiating infection process [2] (Fig. 1 ). In support of this hypothesis, quercetin was active against infection in a model of virus cell entry and also inhibited the 3C-like protease of SARS-CoV in vitro [3], [4]. Based on these findings, it has been suggested that quercetin be incorporated into trials against Covid-19 [5].

Fig. 1.

Interaction between ACE2 and the viral spike protein leading to infection. Representation of the interaction of an inhibitory ligand on the interface between ACE2 and the viral spike protein. The epithelial cells at the infection site express the enzymes ACE2, ADAM-17 and TMPRSS2 on the outer surface. The SARS-CoV-2 virus spike protein binds to the ACE2 enzyme as the very first step of a potential invasion. If this occurs, then the proteases ADAM-17 or TMPRSS2 can cleave ACE2, and in the case of the latter, also cleave the spike protein leading to infection of the epithelial cells and beginning of the invasion [18]. A ligand that binds to the interface of the ACE2 protein and the viral spike protein can inhibit the interaction, reducing the chance of infection. Note that the ligands that bind to the interface are not necessarily inhibitors of ACE2 enzyme activity. ADAM-17, ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17; TMPRSS2, Transmembrane protease, serine 2.

2. Bioavailability

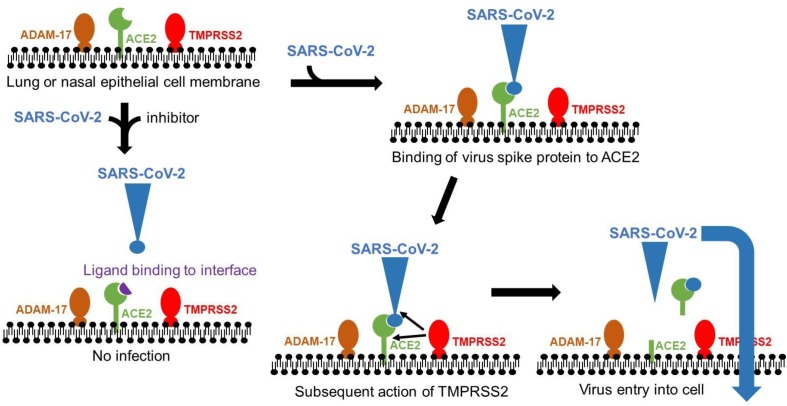

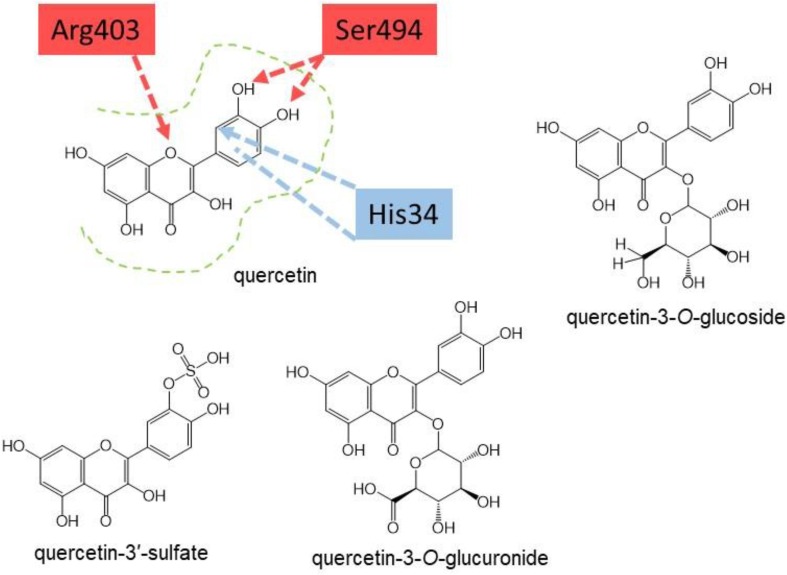

A key aspect of the therapeutically successful action of any drug is delivery to the appropriate site of action. When targeting the interaction of the Viral Spike Protein with ACE2 on the surface of the epithelial cells, the proposed bioactive molecule must reach that site at a concentration sufficient to interfere with the interaction. Based on in silico modelling [2] where the energy of the interaction (Vina score) was ~ -30,500 J/mol, quercetin would theoretically give 50% inhibition (based on ΔG = -RT ln Ka, where ΔG is the change in Gibbs free energy, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, Ka is the association constant; assumption here is that Vina score in silico ≈ ΔG) at a concentration of very approximately 7 μM. This calculation serves to help estimate the dose that might be needed at the site of action. Quercetin is a plant-based naturally occurring flavonoid. Plants store quercetin attached to sugars which substantially interfere with protein interactions [6] but are released in the human digestive tract [7]. The oral bioavailability of quercetin is very well understood [8]. Even after administration of a high oral dose of quercetin, the maximum concentration of the free aglycone in plasma is only in the low nM range [9], several orders of magnitude lower than required based on the above calculation. Canonical drug-metabolising pathways [10] convert most of the quercetin to sulfate, glucuronide and methyl conjugates. The concentration at the necessary site of action would therefore not match or even approach that required for an effect even with very large doses. However, although oral administration of quercetin is unlikely to be effective in disrupting SARS-CoV-2 Viral Spike Protein/ACE2 interactions (Fig. 2 ), other routes of delivery could be effective. A nasal spray containing quercetin in a suitable form could deliver the appropriate concentration directly in the active molecular form, i.e. free unconjugated quercetin. Any formulation could include agents to improve stability and solubility [11].

Fig. 2.

Putative interactions between quercetin and the ACE2-spike protein interface. The residues shown are redrawn for quercetin based on the interaction reported for the related flavonoid eriodictyol [2]. Amino acids in red belong to the spike protein and those in blue to ACE2. The structures of the two most abundant quercetin conjugates found in the blood after oral consumption of quercetin [6], [7], [9] are shown to illustrate that the bulky attached moieties would preclude binding to the same site as quercetin. Quercetin-3-O-glucoside is also shown as the major form of quercetin in onions [19] before digestion, which has a bulky glucose moiety attached. The crystal structure between ACE2 and the viral spike protein has recently been refined [20]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

3. Doses required

For a solution of quercetin to be active, a target of at least three times the inhibition constant is reasonable at the site of interaction, i.e. ≥ 25 μM (≥ 7.6 μg/ml). A single 10 ml nasal dose would therefore need to contain ~ 76 μg of quercetin. Although the required effective dose of quercetin is contained, for example, in only ~ 0.06 g of fresh red onion (www.phenol-explorer.eu), eating even large amounts of onions would not be effective owing to the bioavailability issues raised above. These points highlight that if any clinical studies were to be conducted to harness the in silico and in vitro data, the delivery method of the bioactive molecule is of critical importance. The United States Food and Drug Administration has already approved oral doses of quercetin as safe for human consumption. Quercetin given nasally was effective in a rat model of allergic rhinitis [12], and the safety of quercetin has been favourably assessed [13]. Quercetin at high doses, like any other bioactive compound, could have potentially off-target effects. Following local application by a nasal spray the possibility exists that quercetin could be transported or diffuse to other tissues such as the lungs and blood. Previously found beneficial effects on cardiovascular health biomarkers after regular consumption of quercetin [14] could deliver an additional positive outcome. Patients with pre-existing cardiometabolic syndromes such as hypertension are at increased risk during Covid-19 infection, and the protective effects of quercetin increase the justification for trials. However, quercetin treatment should be cautioned in the case of pre-existing lung cancer. Although many of the effects of quercetin were beneficial in that setting, the fact that quercetin can reprogram cellular energy metabolism should be taken into account [15], [16]. We have recently published a review which traces the history of research on quercetin and other flavonoids [17]. One study on Covid-19 and quercetin has so far been entered into www.clinicaltrials.gov (20th June 2020), and the ready availability of quercetin and its low toxicity [13] supports the potential beneficial outcomes of clinical trials involving quercetin [5].

4. Recommendations

We encourage researchers to consider bioavailability issues before embarking on expensive clinical trials. Based on the evidence presented here, it is possible that a nasal spray of dilute quercetin in a suitable vehicle, administered regularly at low doses during the early stages of infection, could attenuate entry of the virus into cells and so halt progress of the infection, possibly leading to a reduced need for hospitalisation. We suggest that clinical trials should be conducted in a timely fashion to test this. However, we emphasize that oral administration of even high doses of quercetin, either as a drug in pure form or in food, is unlikely to be successful owing to the known metabolism of quercetin, involving extensive conjugation and leading to low plasma concentrations of free quercetin.

5. Authors’ contributions

Both authors contributed equally to writing the article.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sungnak W.H., Bacavin N., Berg C.M. SARS-CoV-2 entry genes are most highly expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells within human airways. Quant. Biol. 2020:[q-bio.CB]. arXiv:2003.06122. [Google Scholar]

- 2.M.S. Smith, J.C., Repurposing therapeutics for COVID-19: Supercomputer-based docking to the SARS-CoV-2 Viral Spike Protein and Viral Spike Protein-Human ACE2 Interface, ChemRxiv http://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv.11871402.v4 (2020).

- 3.Yi L., Li Z., Yuan K., Qu X., Chen J., Wang G.H. Small molecules blocking the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into host cells. J. Virol. 2004;78:11334–11339. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11334-11339.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen T.T., Woo H.J., Kang H.K., Nguyen V.D., Kim Y.M., Kim D.W. Flavonoid-mediated inhibition of SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease expressed in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012;34:831–838. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0845-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sargiacomo C., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. COVID-19 and chronological aging: senolytics and other anti-aging drugs for the treatment or prevention of corona virus infection? Aging. 2020 doi: 10.18632/aging.103011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day A.J., Bao Y., Morgan M.R.A., Williamson G. Conjugation position of quercetin glucuronides and effect on biological activity. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2000;29:1234–1243. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Rio D., Rodriguez-Mateos A., Spencer J.P., Tognolini M., Borges G., Crozier A. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2013;18:1818–1892. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almeida A.J.B., Piskula G.I.A., Tudose M., Tudoreanu A., Valentova L., Williamson K., Santos G. Bioavailability of quercetin in humans with a focus on interindividual variation. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety. 2018;17:714–731. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullen W., Boitier A., Stewart A.J., Crozier A. Flavonoid metabolites in human plasma and urine after the consumption of red onions: analysis by liquid chromatography with photodiode array and full scan tandem mass spectrometric detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1058:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y.K., Chen S.Q., Li X., Zeng S. Quantitative regioselectivity of glucuronidation of quercetin by recombinant UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 1A9 and 1A3 using enzymatic kinetic parameters. Xenobiotica. 2005;35:943–954. doi: 10.1080/00498250500372172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao J., Yang J., Xie Y. Improvement strategies for the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble flavonoids: An overview. Int. J. Pharm. 2019;570 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sagit M., Polat H., Gurgen S.G., Berk E., Guler S., Yasar M. Effectiveness of quercetin in an experimental rat model of allergic rhinitis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:3087–3095. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4602-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andres S., Pevny S., Ziegenhagen R., Bakhiya N., Schafer B., Hirsch-Ernst K.I., Lampen A. Safety aspects of the use of quercetin as a dietary supplement. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018;62 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201700447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menezes R., Rodriguez-Mateos A., Kaltsatou A., Gonzalez-Sarrias A., Greyling A., Giannaki C. Impact of flavonols on cardiometabolic bBiomarkers: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled human trials to explore the role of inter-individual variability. Nutrients. 2017;9 doi: 10.3390/nu9020117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerimi A., Williamson G. Differential impact of flavonoids on redox modulation, bioenergetics and cell signalling in normal and tumor cells: a comprehensive review. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018;29:1633–1659. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pesatori P.A., Lam T.K., Rotunno M., Lubin J.H., Wacholder S., Consonni D. Dietary quercetin, quercetin-gene interaction, metabolic gene expression in lung tissue and lung cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:634–642. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson G., Kay C.D., Crozier A. The bioavailability, transport, and bioactivity of dietary flavonoids: A review from a historical perspective. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety. 2018;17:1054–1112. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao L., Sakagami H., Miwa N. ACE2: The key molecule for understanding the pathophysiology of severe and critical conditions of COVID-19: Demon or angel? Viruses. 2020;12:491. doi: 10.3390/v12050491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price K.R., Rhodes M.J.C. Analysis of the major flavonol glycosides present in four varieties of onion (Allium cepa) and changes in composition resulting from autolysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1997;74:331–339. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]