Abstract

Background

How coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) is affecting management of myocardial infarction is a matter of concern, as medical resources have been massively reorientated and the population has been in lockdown since 17 March 2020 in France.

Aims

To describe how lockdown has affected the evolution of the weekly rate of myocardial infarctions (non-ST-segment and ST-segment elevation) hospital admissions in Lyon, the second largest city in France. To verify the trend observed, the same analysis was conducted for an identical time window during 2018–2019 and for an unavoidable emergency, i.e. birth.

Methods

Based on the national hospitalisation database [Programme de médicalisation des systèmes d’information (PMSI)], all patients admitted to the main public hospitals for a principal diagnosis of myocardial infarction or birth during the 2nd to the 14th week of 2020 were included. These were compared with the average number of patients admitted for the same diagnosis during the same time window in 2018 and 2019.

Results

Before lockdown, the number of admissions for myocardial infarction in 2020 differed from that in 2018–2019 by less than 10%; after the start of lockdown, it decreased by 31% compared to the corresponding time window in 2018–2019. Conversely, the numbers of births remained stable across years and before and after the start of lockdown.

Conclusion

This study strongly suggests a decrease in the number of admissions for myocardial infarction during lockdown. Although we do not have a long follow-up to determine whether this trend will endure, this is an important warning for the medical community and health authorities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Myocardial infarction, Acute coronary syndrome

Résumé

Contexte

En France, la pandémie au coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) a nécessité un confinement de la population depuis le 17 mars 2020 et a conduit à réorienter massivement les ressources médicales vers la prise en charge des patients infectés au SARS-Cov-2. Les répercussions sur la prise en charge de l’infarctus du myocarde semblent préoccupantes.

Objectifs

Décrire comment le confinement de la population a affecté l’évolution du taux hebdomadaire d’hospitalisations pour infarctus du myocarde (syndrome coronaire aiguë avec et sans sus-décalage du segment ST) en le comparant à l’évolution du nombre d’accouchements à Lyon, deuxième plus grande ville de France.

Méthodes

Sur la base de la base de données nationale d’hospitalisation (PMSI), tous les patients admis dans les principaux hôpitaux publics pour un diagnostic principal d’infarctus du myocarde ou d’accouchement au cours de la 2e à la 14e semaine de 2020 ont été inclus. Ceux-ci ont été comparés au nombre moyen de patients admis pour le même diagnostic au cours de la même période en 2018 et 2019.

Résultats

Avant le confinement, le nombre d’admissions pour infarctus du myocarde en 2020 différait de celui de 2018–2019 de moins de 10 % ; pendant le confinement, il a diminué de 31 % par rapport à la fenêtre temporelle correspondante en 2018–2019. À l’inverse, le nombre de naissances est resté stable au fil des années et pendant le confinement.

Conclusion

Ce travail objective une diminution inquiétante du nombre d’admissions pour infarctus du myocarde pendant le confinement. Un suivi à plus long terme permettra de voir si cette tendance perdurera et d’en étudier les conséquences. Il s’agit d’un signal d’alarme pour la communauté médicale et les autorités sanitaires.

Mots clés: COVID-19, Infarctus du myocarde

Background

The eruption of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) has dramatically affected healthcare systems worldwide. To deal with this unprecedented challenge, most medical resources have been reorientated towards COVID-19 management to avoid saturation of hospitalisation facilities. Furthermore, most governments have opted for population lockdown to limit virus transmission; in France, lockdown started on 17 March 2020. Even when they had signs of viral infection, patients were urged to stay at home, provided they were not breathless. The unique situation generated by COVID-19 has resulted in important medical problems, and even major surgeries were postponed. The management of patients with myocardial infarction may also have been jeopardised, as has recently been suggested by an increase in the reperfusion delay in a small series of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in China [1] and a decrease in STEMI activation in the cathlab in the US [2]. Currently, the population is being overwhelmed by messages from authorities and the media about COVID-19 that could lessen the perception of other risks. This could reinforce the reluctance and fear of patients to seek medical help, considering the overstretched healthcare workers and the hazardousness of the hospital environment. We believe that this may have affected the rate of cardiac emergencies such as myocardial infarctions. Such an ancillary consequence of COVID-19 could be devastating, due to the high mortality rate of myocardial infarction without revascularisation and to its related risk of late heart failure [3]. If proven true, this should lead the medical community to stress the need for continued commitment for other life-threatening situations to avoid a superimposed cardiovascular tragedy.

The objective of this study was to describe the weekly rate of hospital admissions for myocardial infarction [STEMI and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)] during the first trimester of 2020 in three public centres (including two university hospitals) in Lyon, the second largest city of France. These three centres represent 75% of the intensive care unit (ICU) capacity in the area. We used two comparators:

-

•

a historical one, which was the same analysis of the weekly rate of myocardial infarction during the same time period during the 2 preceding years;

-

•

a pragmatic one, considering an emergency that cannot be changed or left unrecognised (i.e. birth).

Methods

Study design

Patients hospitalised in Croix-Rousse University Hospital, Louis-Pradel University Hospital, or Saint-Joseph Hospital (Lyon, France) with a principal diagnosis of myocardial infarction (STEMI or NSTEMI) or birth were identified during three study periods of the same duration (13 weeks):

-

•

Monday 6 January 2020 to Sunday 5 April 2020;

-

•

Monday 7 January 2019 to Sunday 7 April 2019;

-

•

Monday 8 January 2018 to Sunday 8 April 2018.

The identification of hospital stays was based on the national hospitalisation, Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d’Information (PMSI) database, which covers hospital care, inspired by the US Medicare system. In the PMSI system, identified diagnoses are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). Hospital stays with a principal diagnosis (i.e. the health problem that justified admission) of myocardial infarction (codes I21, I22) or French diagnosis-related group (DRG) of birth (codes 14Z13, 14Z14) were identified. Data collection was performed on 10 April 2020 by the department of Medical Information, Hospices Civils de Lyon, France. The study was conducted retrospectively and, as patients were not involved in its conduct, there was no effect on their care. Ethical approval was not required, as all data were anonymised.

Outcomes

Weekly numbers of myocardial infarctions and births.

Statistical analysis

This was a descriptive analysis of the weekly numbers of myocardial infarctions and births occurring during 2020 compared with an average of these numbers in 2018 and 2019. Two periods were defined: before the lockdown period (weeks 2–10) and during the lockdown period (weeks 11–14). Figures were plotted using Graphpad Prism 7.04 software.

Results

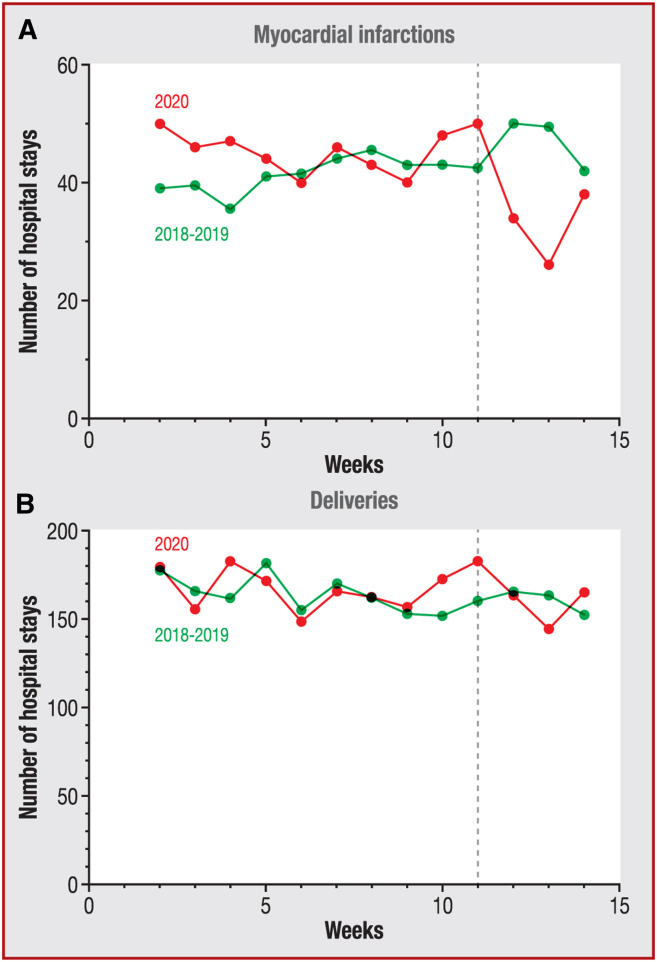

The weekly numbers of myocardial infarctions were roughly comparable before the lockdown period in 2020 and in 2018–2019. After lockdown, it dropped to a much lower level in 2020 versus 2018–2019 (Fig. 1 A). Table 1 indicates that the cumulative incidence of myocardial infarctions during weeks 2–10 in 2020 differed from that in 2018–2019 by less than 10%, but markedly decreased by 31.0% during lockdown. However, the numbers of births remained stable over the study periods, without a substantial difference between 2020 and 2018–2019 (Fig. 1B). Lockdown had almost no effect on the numbers of births (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Weekly numbers of A. myocardial infarctions and B. births. Dashed line indicates the start of lockdown. [Note to journal: please alter y axes to “Weekly number of hospital stays”; remove “Myocardial Infarctions” and “Deliveries”; en rule in 2018–2019; remove boxes round A and B].

Table 1.

Number of myocardial infarctions and births.

| Before lockdown | During lockdown | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | 2018–2019 | 2020 | 2018–2019 | 2020 | ||

| Weeks | 2–10 | 2–10 | Change | 11–14 | 11–14 | Change |

| Myocardial infarctions | 414 | 454 | +9.7% | 142 | 98 | –31.0% |

| Births | 1635 | 1672 | +2.3% | 480 | 472 | –1.7% |

Discussion

The upheaval induced by COVID-19 has many non-viral consequences and our multi-centre study is the first one to tackle the issue of its effect on myocardial infarctions. The present study strongly suggests a decrease in the number of admissions for myocardial infarction during lockdown. Although we do not have a long follow-up to determine whether this trend will continue, this is an important warning for the medical community and authorities.

We paid great attention to methodological issues to provide robust descriptive data. The historical and pragmatic controls were used to rule out an artefactual drop in admissions for myocardial infarction. There may be several explanations for our findings, with different epidemiological consequences in the long term. Our driving hypothesis is that insufficient patients are requesting help as they were urged to stay at home and were scared to go to the hospital, which was no longer seen as a safe place. This may be further aggravated by some misdiagnosis by physicians who are “COVID-minded” and who may not recognise true acute coronary syndromes among the various chest pains associated with COVID-19 infection. A competitive risk may also play a role, with some people dying from COVID-19 before suffering a myocardial infarction. One also has to recognise that a true decrease in myocardial infarction may also be observed with the reduction of physical activities due to lockdown, exercising being acutely associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction [4]. With lockdown, a reduction in pollution has also been observed, which may also produce favourable effects in terms of myocardial infarction [5]. Although possible, we think that these favourable effects are likely of low importance, given the known associations between viral illnesses and acute coronary events [6]. In addition, a recent study showed a 25% reduction in on STEMI admissions during the pandemic compared with the same period in 2019 [7]. The authors suggested a possible temporary “stunning” of some diseases in extraordinary situations, such as war or a worldwide health crisis. Finally, it is unlikely that patients presenting with an acute coronary syndrome were directed to other centres or other cities, as all percutaneous coronary intervention centres were fully involved and impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are, of course, important limitations with respect to the duration of the study and the type of myocardial infarction, which was not available in the PMSI data. However, we felt that it was crucial to rapidly communicate this threat that may lead to more severe consequences than the COVID-19 infection per se.

At this stage, we can only speculate, but it is fair to say that we must stay in alert with respect to cardiac emergencies and probably other domains, given the uncertainty of pandemic evolution. For us, there are two major consequences for our healthcare systems and for policies:

-

•

we should be prepared to accept intertwined COVID-related and COVID-unrelated cardiac emergencies through dedicated pathways and experienced caregivers;

-

•

we should reorient communications – at a medical and political level – to a more balanced message indicating that COVID-19 should not prevent care for other pathologies that may be more lethal.

In any case, monitoring the consequences of this crisis for the health of populations by large epidemiological studies will be mandatory.

Limitations

We cannot exclude an effect of seasonality; however, to mitigate this bias, we included patients over a 3-year period during the same weeks. Larger epidemiological studies are warranted to precisely measure the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the occurrence and prognosis of cardiovascular accidents.

Conclusions

The medical community and policymakers should be concerned about this unexpected decrease in admissions for myocardial infarction to avoid superimposing a cardiovascular disaster on top of the viral pandemic. While everybody is learning day by day how to deal with this unprecedented situation, which could be a lengthy process, we should not neglect other medical problems.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Sylvie Dargent and Dr Philippe Poirie for their help in collecting the data.

References

- 1.Tam C.F., Cheung K.S., Lam S., Wong A., Yung A., Sze M., et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006631. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kloner R.A. Can we trigger an acute coronary syndrome? Heart. 2006;92:1009–1010. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.086652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerber Y., Weston S.A., Enriquez-Sarano M., Berardi C., Chamberlain A.M., Manemann S.M., et al. Mortality associated with heart failure after myocardial infarction: a contemporary community perspective. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002460. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strike P.C., Perkins-Porras L., Whitehead D.L., McEwan J., Steptoe A. Triggering of acute coronary syndromes by physical exertion and anger: clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. Heart. 2006;92:1035–1040. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.077362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajagopalan S., Al-Kindi S.G., Brook R.D. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2054–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong J.C., Schwartz K.L., Campitelli M.A., Chung H., Crowcroft N.S., Karnauchow T., et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:345–353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Range G., Hakim R., Motreff P. Where have the STEMIs gone during COVID-19 lockdown? Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa034. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]