Highlights

-

•

MG treatment in the context of COVID-19 should be tailored to the patient.

-

•

Patient’s respiratory status should be closely monitored.

-

•

Concomitant COVID-19 and MG has a variable response to treatment.

Keywords: Neuromuscular, Covid-19, Myasthenia Gravis, Exacerbation, SARS CoV2

1. Introduction

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is a disorder of neuromuscular transmission in which antibodies bind to acetylcholine receptors or to functionally related molecules at the neuromuscular junction. It presents with variable, fluctuating muscle weakness, most commonly affecting the ocular, bulbar, respiratory and limb muscles (generalized MG)

These symptoms can rapidly worsen (“exacerbation”) with potential for airway compromise (“crisis”) due to triggers such as infection. Plasma exchange (PLEX) and Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIg) are the mainstay of management during such episodes [1].

Given that many MG patients are on immune-modulating medications, there’s possibly an increased risk of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV 2) [2]. Per the Centers for Disease Control, symptoms from SARS CoV 2 can include fever, cough, respiratory distress, diarrhea, and reduction of smell and taste sensations [3]. Additionally, if there is coexisting respiratory muscle weakness, MG patients can be at an increased risk of COVID-19-related complications [2].

In this case report, we discuss the presentation of a generalized MG exacerbation with co-existing COVID-19 symptoms and its management.

2. Case report

A 36-year-old female had been diagnosed with seronegative (acetylcholine receptor binding antibody negative and MuSk antibody negative) generalized MG via repetitive nerve stimulation two years ago when she presented with progressive limb weakness, fatigable ptosis, dysphagia and exertional dyspnea.

At baseline, she was stable; her Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily living score (MG-ADL) was eight, and her Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) class was 2A and MG-Composite was 13. Her last exacerbation was 6 months prior to this episode when she presented with worsening dysphagia and exertional dyspnea. She was treated with PLEX with significant improvement in symptoms.

At the time of her current presentation, she was on Prednisone 25 mg daily for 4 months (was on 40 mg daily at diagnosis), Mycophenolate Mofetil 1000 mg twice daily (for 20 months) and Pyridostigmine 60 mg three times a day (for 24 months). She was also treated with maintenance IVIg every 10 weeks. She had undergone thymectomy about a year and half ago (thymic hyperplasia seen on biopsy). There was no other past medical history.

The patient had a history of air travel to Massachusetts 10 days prior to symptom onset. She now presented with worsening ptosis, dysphagia, weakness and shortness of breath concerning for a MG exacerbation. In addition, she reported cough, fever and loss of sense of smell. Patient's labs showed elevated white count (15.22 × 109/L) with lymphopenia (0.58 × 109/L). Respiratory pathogen panel including Influenza A/B and Streptococcus pneumonia came back negative. Given recent travel with cough and fever on presentation, she was tested for COVID-19 Real Time-Polymerase Chain Reaction primers (RT-PCR) with Centers for Disease Control (RT-PCR), which came back positive. Pulmonary function tests were deferred at that time, but an Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) showed PaO2 of 90 mmHg (normal: 75 mmHg–100 mmHg) and PaCO2 50mmg (normal: 35 mmHg-4 5 mmHg). She was admitted for management of her MG exacerbation symptoms. Her MG composite was 19.

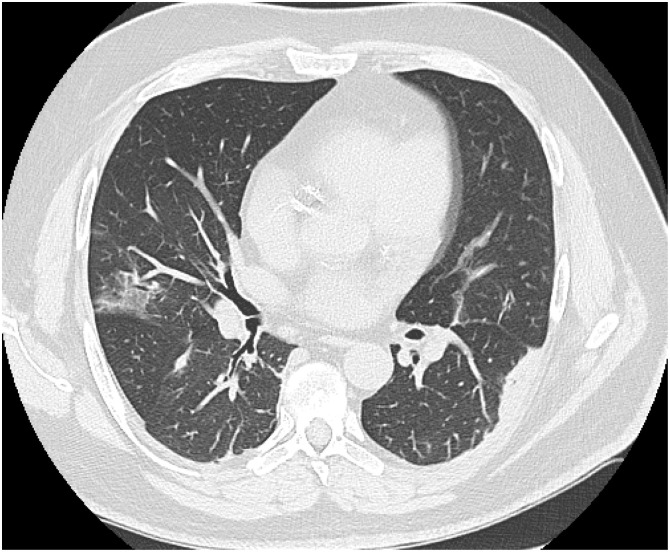

Her initial treatment regimen included supportive care for COVID-19 and PLEX for MG exacerbation. Pyridostigmine was held, but we continued mycophenolate in addition to stress dose IV steroids (oral prednisone was stopped). Three days after starting treatment, her respiratory status worsened. ABG done at that time showed PaO2 of 50 mmHg and PaCO2 of 60 mmHg, following which she was electively intubated. CT chest showed bilateral ground-glass opacities (Fig. 1 ). Significant labs included an elevated aspartate transaminase 70 U/L (8–48 U/L), alanine transaminase 80 U/L (7–55 U/L), L-lactate dehydrogenase 300 U/L (122–222 U/L), and ferritin 400 micrograms/L (11–307 micrograms per liter). D-dimer was also elevated at 300–600 ng/mL Fibrinogen Equivalent Units (FEU) (normal: less than 500 ng/mL FEU). The patient remained intubated for the next 14 days during which she received PLEX therapy (a total of 5 exchanges done every other day) in addition to stress dose steroids. She remained in the hospital for an additional 7 days post extubation before being discharged to her home. She resumed her home dose prednisone (25 mg daily) and mycophenolate mofetil (1000 mg twice daily) at discharge. At follow-up one-month post discharge, the patient was back to her baseline with regards to myasthenic symptoms (MG-ADL was 7 and MG composite was 14), but she continued to report a loss of sense of smell.

Fig. 1.

A 36-year old female with a history of generalized Myasthenia Gravis presented with worsening muscle weakness and shortness of breath. On evaluation, she was also found to be positive for SARS COV-2. She was hospitalized and treated with Plasma Exchange with her home dose of Mycophenolate Mofetil continued. Her respiratory status worsened three days after admission, showing bilateral ground glass opacities as seen in the CT chest below. Patient was intubated for 14 days before being discharged to home.

3. Discussion

COVID-19 infection in MG can be challenging for multiple reasons: infections are known to trigger MG exacerbations/crises, MG patients may be at increased risk of such infections due to immunosuppressive medications, and respiratory distress can be seen in both conditions which can complicate identification and management.

Recently, a panel of MG experts [2] provided guidance on MG management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Per their recommendations, therapy decisions should be tailored to each patient; immunosuppressive medication should be continued, unless specifically discussed and approved by healthcare providers. Furthermore, they recommend continuing the current MG standard of care treatment during hospitalizations. There may be a need to increase corticosteroid dose as is typical in infection/stress steroid protocols; however, if COVID-19 symptoms are severe, it may be important to temporarily pause immunosuppression. Immune depleting agents should be avoided, whereas standard immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and mycophenolate can be continued given that they are longer acting (similar to our case). In addition, there is currently no evidence suggesting that IVIG or PLEX increase the risk of COVID-19 infections [2].

For our patient, in accordance with the guidelines, we continued the standard of care treatment for MG exacerbations due to her significant decline. She was continued on Mycophenolate Mofetil, and we gave her stress dose steroids during the hospital stay. We held her Pyridostigmine as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may lead to excessive bronchial secretions and further complications during hospitalizations. Finally, given her initial presentation and to prevent further MG-related complications, we continued her home medication regimen upon discharge.

There appears to be considerable variability in how MG patients respond to COVID-19, however. Anand et al. [4] describe the course of COVID-19 in five hospitalized patients with MG (four with AchR antibodies and one with MuSK antibody). Hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 was reported in three patients, requiring either high flow oxygen or intubation. A milder course of illness without respiratory complications was seen in the remaining two. It’s unclear why one patient may perform better than another, but it’s plausible it may relate to comorbidities and how soon a patient received care.

Outcomes also don’t seem to be related to the immunosuppressive dosing. Anand et al. [4] decided to hold the home dose of Mycophenolate Mofetil in two of their patients; however, no pattern of outcomes emerged from that. They also report uncertainty of any impact of discontinuation as the drug can remain active for up to 6 weeks after cessation, as has been recommended by Jacob et al. (2020). Additional guidelines from Solé et al. [5] suggest caution in using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, two experimental COVID-19 treatments, in MG patients as they may contribute to a worsening of myasthenic symptoms. Thus, an individualized approach to management seems best suited.

4. Conclusion

MG treatment in the context of COVID-19 should be tailored to the patient, with close monitoring of the patient’s respiratory status given the possibility of complications from both the infection and MG.

References

- 1.Sanders D.B. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology. 2016;87(4):419–425. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob S. Guidance for the management of myasthenia gravis (MG) and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020;412 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116803. p. 116803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control; 2020. Symptoms of Coronavirus.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html Updated March 20, 2020. Accessed May 4, 2020, website. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand P. COVID-19 in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mus.26918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solé G. Guidance for the care of neuromuscular patients during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak from the French Rare Health Care for Neuromuscular Diseases Network. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 2020;176(6):507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]