Abstract

Objective:

To report population age-specific prevalence of core cerebrovascular disease lesions (infarctions, cerebral microbleeds, and white-matter hyperintensities detected with magnetic resonance imaging); estimate cut points for white-matter hyperintensity positivity; investigate sex differences in prevalence; and estimate prevalence of any core cerebrovascular disease features.

Patients and Methods:

Participants in the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, age 50 to 89 years, underwent fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and T2* gradient-recalled echo magnetic resonance imaging to assess cerebrovascular disease between October 10, 2011, and September 29, 2017. We characterized each participant as having infarct, normal vs abnormal white-matter hyperintensity, cerebral microbleed, or a combination of lesions. Prevalence of cerebrovascular disease biomarkers was derived through adjustment for nonparticipation and standardization to the population of Olmsted County, Minnesota.

Results:

Among 1,462 participants without dementia (median [range] age, 68 [50–89] years; men, 52.7%), core cerebrovascular disease features increased with age. Prevalence (95% CI) of cerebral microbleeds was 13.6% (11.6%–15.6%); infarcts, 11.7% (9.7%–13.8%); and abnormal white-matter hyperintensity, 10.7% (8.7%–12.6%). Infarcts and cerebral microbleeds were more common among men. In contrast, abnormal white-matter hyperintensity was more common among women age 60 to 79 years and men, age 80 years and older. Prevalence of any core cerebrovascular disease feature determined by presence of at least 1 cerebrovascular disease feature increased from 9.5% (age 50 to 59 years) to 73.8% (age 80 to 89).

Conclusion:

While this study focused on participants without dementia, the high prevalence of cerebrovascular disease imaging lesions in elderly persons makes assignment of clinical relevance to cognition and other downstream manifestations more probabilistic than deterministic.

Introduction

Cerebrovascular disease (CVD) is an important pathologic condition associated with aging and cognitive impairment. Numerous autopsy studies have shown the frequency and effect of CVD in dementia, including of persons with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer clinical syndrome (i.e., clinically probable Alzheimer disease).1, 2 Identification of CVD during life provides a potential biomarker for clinical trials that target cerebrovascular progression and cognitive decline. Studies have evaluated the population prevalence of CVD with brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),3–13 yet different types of cerebrovascular brain lesions (i.e., infarctions, cerebral microbleeds [CMBs], and white-matter hyperintensities [WMHs]) have been reported independently. Report of the population prevalence of all types of CVD lesions in a single study provides improved understanding of the frequency of vascular brain disease in the aging population.

Two commonly used MRI sequences in aging and dementia studies that assess CVD are T2* gradient-recalled echo (GRE), which provides information about CMBs, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI, which provides information about WMHs and infarctions. The objectives of the present study were to 1) report prevalence of infarcts, CMBs, and WMH with suggested cut points in a population-based study; 2) investigate sex-specific prevalences; and 3) provide estimates for the prevalence of any core CVD lesion, to understand the extent of CVD in the population.

Methods

Study Participants

Participants aged 50 to 89 years were enrolled in the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) of Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents. The details of this study have been published previously.14 For the present study, we included participants without dementia: 172 patients with mild cognitive impairment and 1,290 patients who were cognitively unimpaired. The diagnoses of cognitively unimpaired and mild cognitive impairment were based on a consensus conference process that involved the input of the physician who examined the participant, neuropsychologists who reviewed the nine-test neuropsychological battery, and the study coordinator who interviewed both the participant and an informant to complete a clinical dementia rating assessment. The diagnostic criteria for cognitively unimpaired and mild cognitive impairment have been published previously.14

The Rochester Epidemiology Project health records linkage system15 was used to enumerate Olmsted County residents, and an age-and sex-stratified random sample was used to invite participation in the MCSA.16 Participants without contraindications were invited to undergo MRI. In October 2011, T2* GRE sequences were added to the MRI protocol. In this work, we included 1,462 individuals who had usable T2* GRE and FLAIR images between October 10, 2011, and September 29, 2017.

Assessment of Vascular Risk Factors

Using the Rochester Epidemiology Project linkage system, trained nurses abstracted vascular risk factors from health records for each participant including type 2 diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.16 Participants in the MCSA undergo Image result for Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping.

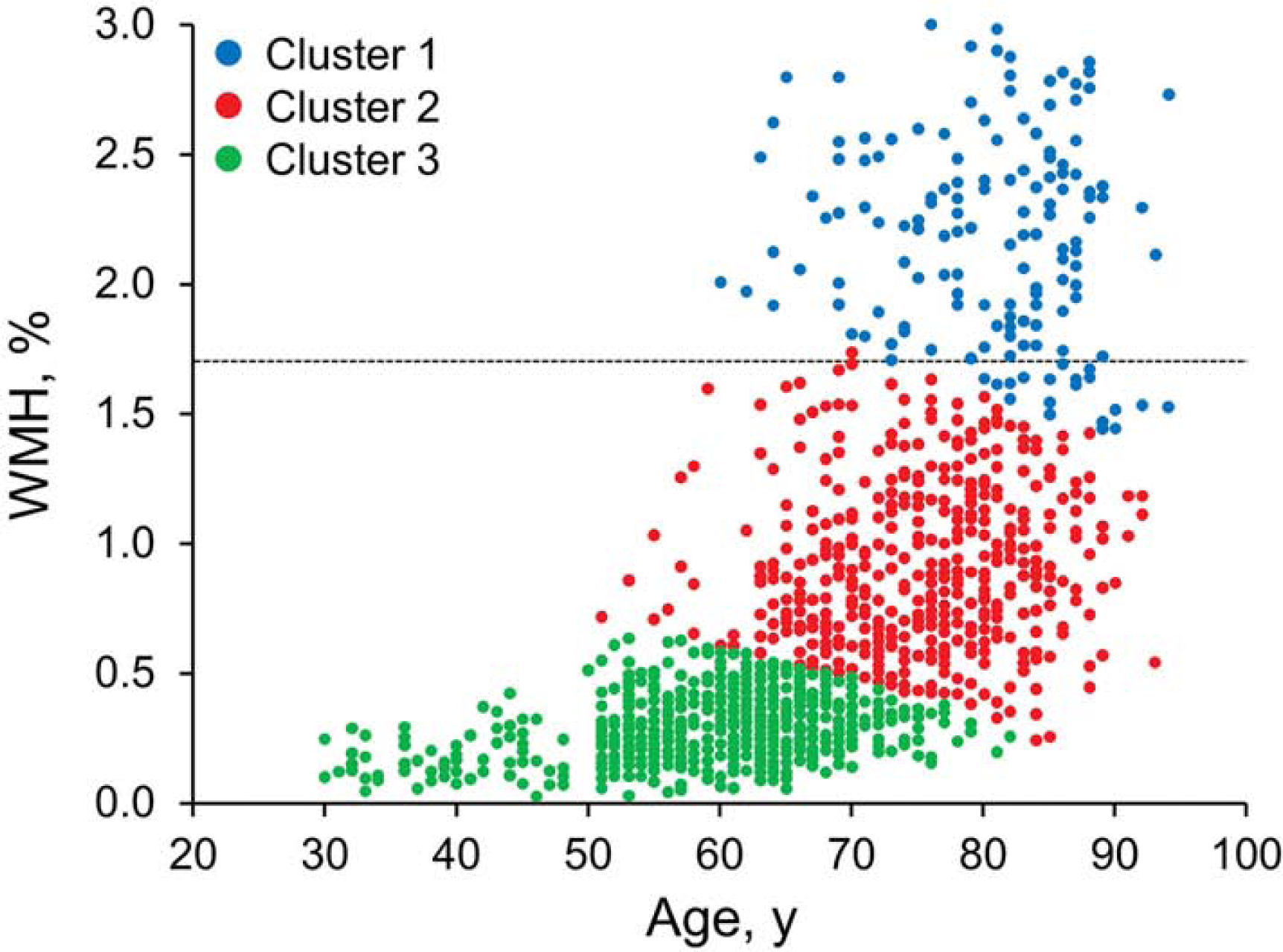

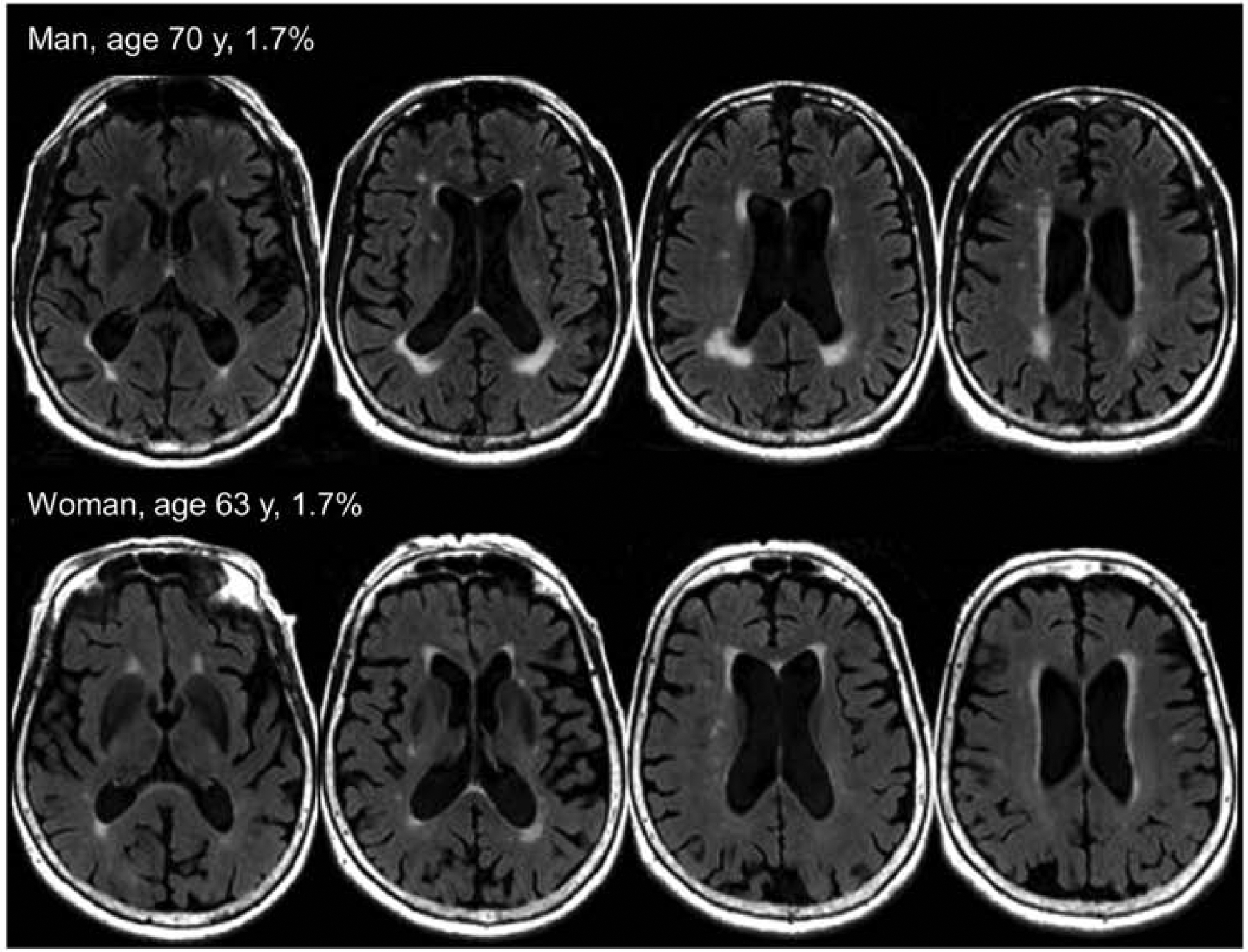

MRI Assessment of WMH and Determination of WMH Positivity

All MRI was acquired on 3T MRI imagers (GE Healthcare). WMH images on standard two-dimensional T2 FLAIR were segmented and edited by a trained imaging analyst with use of a semi-automated method17. WMH scaled by total intracranial volume was our WMH metric. Although we found individuals with little to no WMH, we observed that WMH burden was a continuous distribution with no clear-cut points (Figure 1). Therefore, to determine the persons with high WMH burdens, we fit three Gaussian mixture distributions (with use of maximum likelihood) to the distributions of age vs WMH. We used fitgmdist function from Matlab software (Mathworks, Natick, MA) that returns specified number of clusters fit to the data using iterative expectation-maximization algorithm.18 We were guided by the clearly high WMH cluster that attained a considerable proportion of persons with highly abnormal WMH (Figure 1) and by scan visualization. With this guidance, we chose a cut point of 1.7% WMH of total intracranial volume to identify the individuals with abnormal WMH levels. Figure 2 provides example images at the cut point for abnormal WMH.

Figure 1.

White-matter hyperintensity (WMH) Clustering Used to Determine Cut Point.

Figure 2.

Example T2 Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery Images at the Cut Point for White Matter Hyperintensity.

MRI Examination of CMBs and Determination of CMB Positivity

CMBs were evaluated on a T2* GRE (repetition time/echo time, 200/20 ms; flip angle, 12°; in-plane matrix, 256×224; phase field of view, 1.00; slice thickness, 3.3 mm; acquisition time, 5 minutes). CMBs were defined on the basis of current consensus criteria as homogeneous hypointense lesions in the gray or white matter that were distinct from iron or calcium deposits and vessel flow voids on the T2* GRE images. All possible CMBs were marked by trained image analysts and subsequently confirmed by a vascular neurologist or radiologist experienced in reading T2* GRE and to whom the participants’ clinical information was masked. Full details of the CMB analysis have been published19. Lobar CMBs are associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy, whereas deep CMBs are associated with hypertensive disease20. Consequently, an in-house, automated, anatomical-labeling atlas was used to discriminate lobar regions from deep or infratentorial gray and white-matter regions.

MRI Examinations of Infarcts

Infarcts were graded on two-dimensional FLAIR MRI that was co-registered with an MPRAGE (magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo) T1 MRI. All possible infarcts were initially identified by trained image analysts and subsequently confirmed by a vascular neurologist (JGR) to whom all clinical information was masked. The intra-rater reliability based on blinded reading of 50 possible infarcts on two separate occasions was excellent (k statistic, 0.92).

Cortical infarctions were characterized as hyperintense T2 FLAIR lesions (gliosis) involving cortical gray matter that extended to the cortical edge with or without involvement of the underlying white matter. These infarctions were identified on the T2 FLAIR sequence, with a corresponding T1 hypointensity required for confirmation.

Subcortical infarctions were characterized as hyperintense T2 FLAIR lesions with a dark center, seen in the white matter, infratentorial, and central gray-capsular regions. The dark area (tissue loss) must be greater than or equal to 3 mm in diameter as measured on the T2 FLAIR or T1, whichever image shows the findings more clearly.

Lacunar infarctions were defined as the subgroup of subcortical infarcts 3 to 15 mm in diameter.21 Subcortical infarcts were distinguished from perivascular spacesby size, location, and shape.22 Perivascular spaces were defined as lesions having signal intensity similar to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2) that were linear or tubular and typically less than 3 mm in maximum diameter. On co-registered T2 FLAIR and T1 MRI sequences, symmetrical lesions with smooth defined contours favored perivascular spaces. These infarct criteria are compatible with the Standards for Reporting Vascular changes on nEuroimaging (STRIVE)21 criteria, with modifications as outlined below.

Perivascular spaces occur more frequently in the inferior basal ganglia region and centrum semiovale and follow the course of penetrating vessels. In these regions, the perivascular spaces may be greater than 3 mm.23 Therefore, in the inferior basal ganglia24 and centrum semiovale, the following four criteria had to be met to define the lesion as an infarct rather than a perivascular space: greater than or equal to 3 mm in diameter; not linear or tubular; on T2 FLAIR, central CSF-like hypointensity with a surrounding rim of hyperintensity; and asymmetrical.

Certain locations where infarcts are more likely to occur than the perivascular spaces were graded differently. Infarctions in the areas of the thalamus and caudate did not need to meet the 3-mm diameter criteria, central hypointensity, or surrounding rim of hyperintensity thresholds. In these cases, the central cavity fluid may not be seen on T2 FLAIR, and the lesion may be fully hyperintense while having CSF intensity on T1-weighted image. A subset of cerebellar infarcts with CSF intensity on T2 and T1 MRI sequences may have no hyperintense ring on T2 FLAIR, but the infarcts still needed to meet the 3-mm criteria. Data from prior scans were taken into account. For example, if the new scan shows an incident area of T2 hyperintensity and corresponding T1 cavity, this characteristic would meet criteria of an infarction.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics including median and range for continuous variables and frequency and percent for categorical variables were used to summarize participant characteristics by the decade of age at imaging.

Frequencies of infarcts, WMH, and CMBs were calculated following the original sampling frame with division of the number of observed lesions by the number of imaged participants per age and sex strata. As we have previously described,25 a two-stage inverse probability weighting approach was used to adjust observed frequencies for two possible causes for bias: study nonparticipation and imaging nonparticipation. In short, two sets of weights—one for study participation and one for imaging—were multiplied together to give a single weight to adjust their observations. The adjusted frequency of vascular types was then standardized to the Olmsted County population (2010 US Census) directly by age and sex according to our population-based sampling, to give population prevalence estimates.26

The presented statistical testing was performed at the conventional 2-tailed α level of 0.05. All analyses were performed with statistical software (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center institutional review boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability

Data from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, including data from this study, are available upon request.

Results

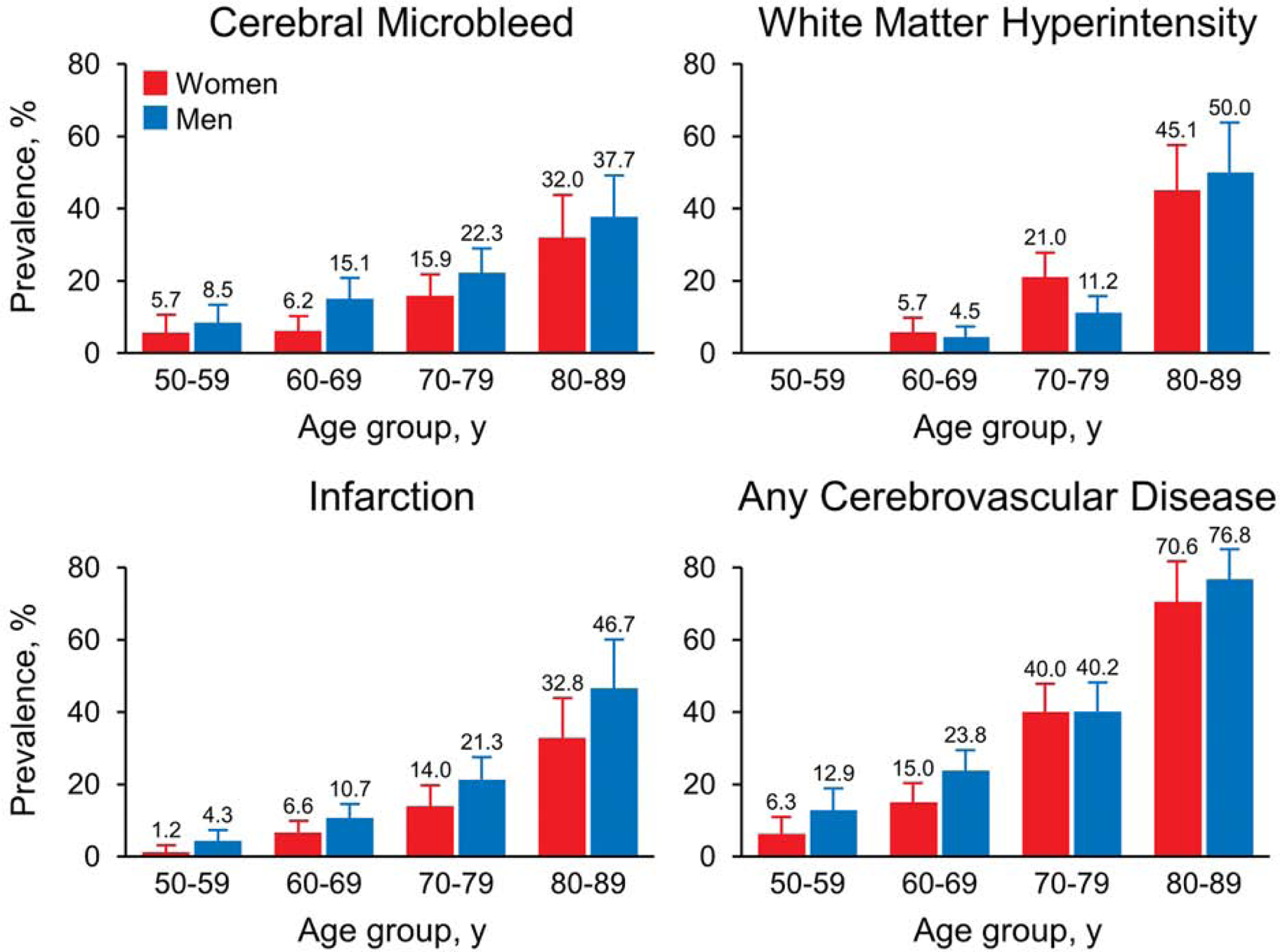

The overall median age of the study population was 68 years (range, 50–89 years), and 52.7% were men (Table 1). Table 2 reports the age-specific prevalence of CMBs, WMHs, and infarcts. The number of all CVD imaging lesions increased with age. The prevalence of cerebrovascular pathologic conditions was tracked for patient decade and sex (Figure 3). CMBs and infarcts occurred more frequently for men, a difference that widens with advancing age for infarcts but not for CMBs. In particular, lobar CMBs are more common in men (Table 2). WMHs meeting the cut-point threshold rapidly increased with older age. The prevalence of WMH is greater for women between ages 60 and 69 years and 70 and 79 years, but this trend reverses at the age decade of 80 to 89 years, when the prevalence is greater in men (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population by Age (N=1,462)

| Age Decade, y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristicb | 50–59 (n=296) | 60–69 (n=522) | 70–79 (n=373) | 80–89 (n=271) |

| Male sex | 153 (51.7) | 261 (50.0) | 195 (52.3) | 161 (59.4) |

| Age, median (range), y | 55 (50–59) | 65 (60–69) | 75 (70–79) | 83 (80–89) |

| Education, median (range), y | 16 (9–20) | 15 (6–20) | 14 (6–20) | 14 (7–20) |

| APOEa | 83 (29.1) | 149 (28.7) | 115 (30.8) | 69 (25.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (1.7) | 26 (5.0) | 36 (9.7) | 60 (22.1) |

| Hypertension | 93 (31.4) | 280 (53.6) | 247 (66.4) | 222 (81.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (10.1) | 75 (14.4) | 69 (18.5) | 61 (22.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 195 (65.9) | 420 (80.5) | 304 (81.7) | 243 (89.7) |

| Coronary artery disease | 20 (6.8) | 88 (16.9) | 104 (28.0) | 123 (45.4) |

| Smoking status (ever) | 111 (37.5) | 242 (46.3) | 188 (50.4) | 115 (42.5) |

APOE4=apolipoprotein Epsilon 4

Values are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless specified otherwise. Data were missing for APOE4‡ (n=14), atrial fibrillation (n=1), hypertension (n=1), diabetes mellitus (n=1), dyslipidemia (n=1), and coronary artery disease (n=1).

Table 2.

Age-Specific Prevalence of Vascular Disease

| Age Decade, yb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrovascular Pathologic Evaluation |

50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 |

| All Patients, Prevalence (95% CI) | ||||

| WMH | — | 5.2 (3.0–7.3) | 16.5 (12.4–20.7) | 47.5 (38.5–56.6) |

| Total CMB | 7.0 (4.0–10.1) | 10.3 (7.3–13.3) | 18.8 (14.6–23.1) | 34.8 (26.9–42.7) |

| Deep CMB | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) | 2.2 (0.7–3.6) | 5.2 (2.9–7.5) | 8.1 (3.2–13.0) |

| Lobar CMB | 6.6 (3.7–9.6) | 8.0 (5.3–10.6) | 15.3 (11.4–19.2) | 27.3 (20.2–34.3) |

| Total infarct | 2.7 (0.9–4.4) | 8.5 (5.8–11.1) | 17.3 (13.2–21.4) | 39.8 (30.5–49.1) |

| Lacunar infarct | 1.7 (0.3–3.1) | 6.7 (4.4–9.0) | 11.3 (8.1–14.5) | 26.1 (18.3–33.9) |

| Cortical infarct | 0.6 (0.0–1.5) | 2.1 (1.0–3.3) | 6.0 (3.3–8.6) | 18.4 (8.5–28.2) |

| Men, Prevalence (95% CI) | ||||

| WMH | — | 4.5 (1.9–7.0) | 11.2 (6.8–15.7) | 50.0 (37.0–63.1) |

| Total CMB | 8.5 (3.8–13.2) | 15.1 (9.9–20.2) | 22.3 (16.1–28.6) | 37.7 (26.5–49.0) |

| Deep CMB | 0.5 (0.0–1.4) | 3.3 (0.5–6.1) | 5.4 (2.2–8.6) | 6.2 (1.7–10.7) |

| Lobar CMB | 8.5 (3.8–13.2) | 12.0 (7.4–16.7) | 19.5 (13.6–25.5) | 30.5 (20.8–40.3) |

| Total infarct | 4.3 (1.1–7.5) | 10.7 (6.8–14.5) | 21.3 (15.2–27.3) | 46.7 (33.1–60.2) |

| Lacunar infarct | 2.3 (0.0–4.7) | 9.1 (5.5–12.8) | 16.5 (11.0–22.0) | 28.4 (16.3–40.4) |

| Cortical infarct | 1.3 (0.0–3.2) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 7.1 (3.5–10.7) | 27.3 (10.4–44.2) |

| Women, Prevalence (95% CI) | ||||

| WMH | — | 5.8 (2.4–9.1) | 21.0 (14.3–27.7) | 45.1 (32.8–57.4) |

| Total CMB | 5.7 (1.7–9.7) | 6.2 (2.9–9.6) | 15.9 (10.1–21.7) | 32.0 (20.1–43.8) |

| Deep CMB | — | 1.2 (0.0–2.4) | 5.1 (1.8–8.4) | 9.9 (1.4–18.4) |

| Lobar CMB | 5.0 (1.2–8.7) | 4.5 (1.7–7.2) | 11.7 (6.5–17.0) | 24.1 (13.5–34.6) |

| Total infarct | 1.2 (0.0–2.8) | 6.6 (2.9–10.3) | 14.0 (8.3–19.6) | 32.8 (21.5–44.0) |

| Lacunar infarct | 1.2 (0.0–2.8) | 4.5 (1.6–7.5) | 6.9 (3.1–10.7) | 28.4 (16.3–40.4) |

| Cortical infarct | — | 1.4 (0.0–2.8) | 5.0 (1.1–8.9) | 9.7 (2.5–16.8) |

Abbreviations: CI= confidence interval; CMB=cerebral microbleed; WMH=white-matter hyperintensity.

Dash indicates no data available.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of Cerebrovascular Imaging Lesions by Age Decade and Sex.

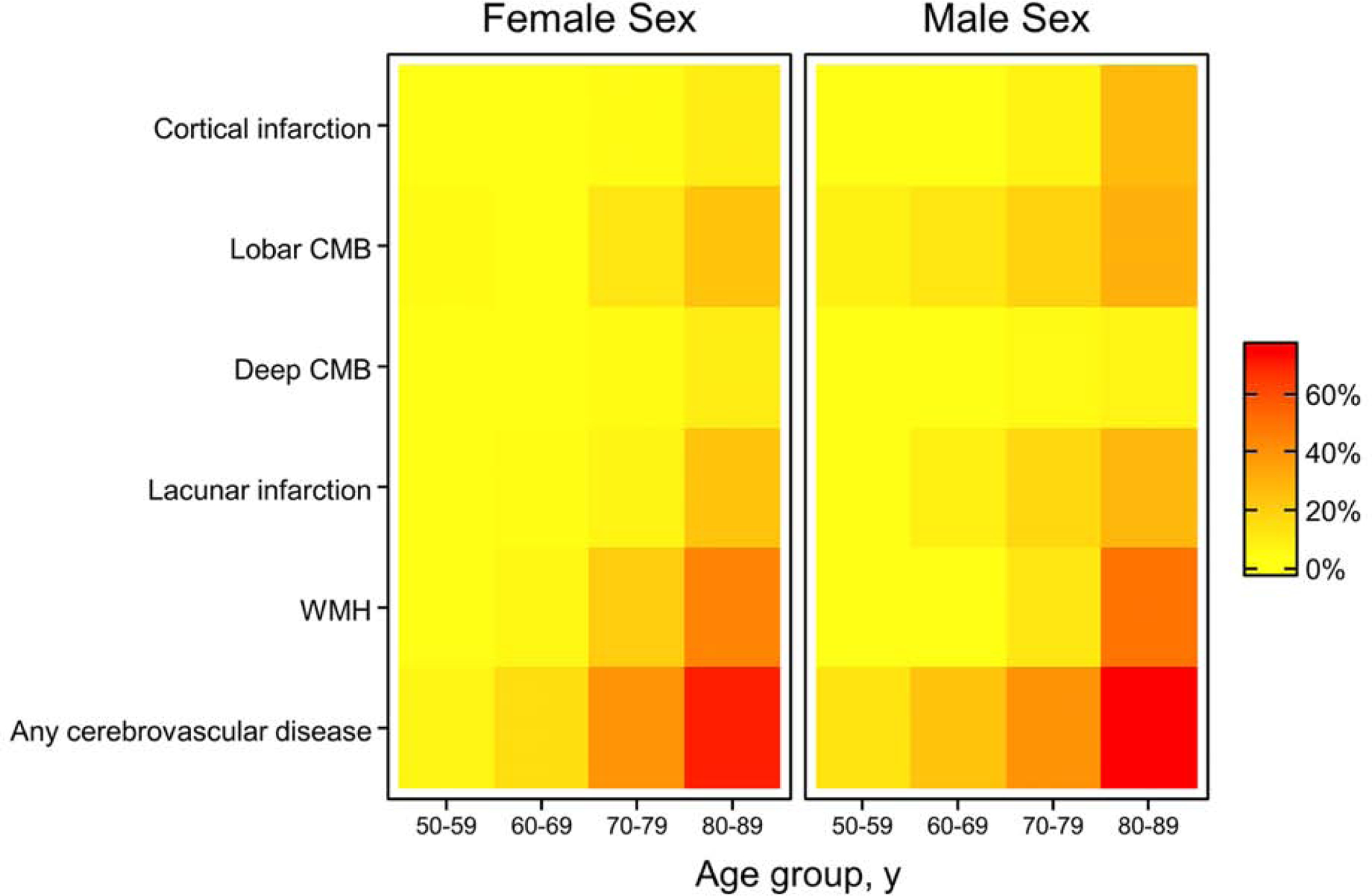

A heat map of cerebrovascular lesions by age, sex, and CVD type shows that the prevalence across CVD types differs vastly (Figure 4). We provide the prevalence of any CVD lesion in the heat map as well as in Table 2, which starts at the low percentage of 9.5% at age 50 to 59 years and increases to 73.8% at age 80 to 89.

Figure 4.

Heat Map of Cerebrovascular Imaging Lesions by Sex. CMB= cerebral microbleed; WMH=white matter hyperintensity.

We further explored how the prevalence of combinations of infarcts, CMBs, and abnormal WMHs differed by age and sex. We found that the prevalence of a combination of all 3 (infarcts, CMB, and abnormal WMH) was 1.8%, whereas the combination of 2 core CVD imaging features varied from 1.5% to 2.9%. These findings suggest that core CVD imaging characteristics tend to cluster as a person ages.

Discussion

The present study had three major findings. First, the high prevalence and heterogeneity of CVD imaging lesions detected on brain MRI increased with age. Second, cerebrovascular pathologic characteristics are more common among men than women, with the exception of WMH, which is more common among women between ages 60 and 79 years. Third, although considerable heterogeneity is observed in the prevalence of each of the core CVD features, the high prevalence of any core CVD feature highlights the need for CVD consideration in clinical and research dementia studies.

The present study extends the findings of prior population- and community-based studies that investigated the prevalence of core CVD lesions. It provides population prevalence (rather than only observed frequencies) of all CVD types through use of the inverse probability weighting approach and of 3T magnetic strength, which may have increased sensitivity for vascular pathologic conditions. In addition, the study provides prevalence estimates of each core CVD feature and any CVD feature. Prior attempts to create a CVD biomarker (V) were exclusively based on FLAIR or were focused on cerebral small-vessel disease as a mechanistic biomarker.27, 28

Infarcts

The apparent prevalence of infarcts in population- and community-based studies varies in accordance with the MRI field strength used, the population studied, and the age of participants. In the Rotterdam Scan Study, the prevalence of infarcts was 24% and increased with age.9 The presence of infarcts in the Framingham Heart Study was 12.3%, and the participants were on average younger than the Rotterdam study participants.8 In a more recent study that looked at the prevalence of lacunar stroke in a community cohort, 7.8% of participants aged 60 to 64 years had lacunar infarcts.5 Despite differences in the populations studied (in the present study, those with dementia were not included) and in MRI strength and parameters used, the similarity is remarkable in the frequency of infarcts compared with the present study when accounting for age differences. Despite similarities in infarct frequency, the frequency differed by sex in the population-based studies. In the Rotterdam study, more women had infarcts, whereas no difference in brain infarcts was detected between men and women in the Framingham study.8, 9 In the present study, infarcts were more common among men. The global incidence of ischemic stroke is greater in men29; similarly, infarcts were more common in men in the present study.

White-matter Hyperintensity

Determination of the prevalence of WMH is more challenging than for infarcts because the distribution of WMH burden is not bimodal. Most studies use validated semi-quantitative scales for WMH grading.30 The apparent prevalence can vary greatly when a cut point is chosen. For example, in the Rotterdam Scan Study, which used a visual grading scale, only 5% of participants had no WMH.11 However, the choice of a more restrictive cut point of 2 mL for subcortical WMH reduces the prevalence substantially.10 Similarly, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study found a high proportion of individuals with WMH and a prevalence that increased from 88% at age 55 years to 92% at age 65.13

Other investigators have dichotomized WMH by considering patients with 1 standard deviation above the average to have large WMHs,31 but this methodology results in the same prevalence for each decade. Most studies have shown that WMH volume and progression tend to be greater in women than men.11, 32 Since few individuals have no WMH as they age, presence or absence of abnormal levels of WMH has been difficult to determine. In contrast to our prior published study, where we reported the cut point for abnormal WMH on the basis of expected frequency of pathologic changes of CVD seen at autopsy,32 in the present study we used an unbiased method to identify a stringent cut point that gathers data about individuals with high levels of WMH. Although the threshold we picked was higher than those previously used in other studies,27, 32 visual inspection of the images at the determined cut point supported our more stringent cutoff and its utility in identification of individuals with positivity for CVD based on WMH.

Cerebral Microbleeds

The prevalence of CMBs in this population was similar to the Rotterdam Scan Study cohort.3, 4 We previously published the prevalence of CMBs and the association with amyloid burden on positron emission tomography (PET).19 In the present study, we investigated the prevalence of CMBs at the time of first GRE. Our previous publication focused on the relationship between amyloid load and CMBs,19 and so the prevalence at the time of Pittsburgh compound B PET scan was used, resulting in slightly different estimates. CMBs increased with age. Lobar CMBs were more common than deep CMBs. Male sex was associated with CMBs, similar to the Framingham Heart Study3 and the Age Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study.3, 6

Prevalence of Cerebrovascular Burden in the Population

Similar to the vascular pathologic disease of individuals, the prevalence of any CVD feature in the study population increased with age and was more common among male participants. Yet, the presence of CVD was not universal even among those older than 80 years. Prior studies have shown that all three of the detected vascular imaging lesions are associated with cognitive decline. Further, in the context of Alzheimer disease biomarkers, the trajectory of cognitive decline is worse when vascular disease (as measured by infarcts or WMH) is present than with Alzheimer disease pathologic change alone.27

Although heterogeneous mechanisms underlie different forms of vascular disease, the estimation of a metric for CVD positivity allows us to understand the extent of CVD in the population. Certain treatments such as antihypertensive agents may reduce the risk of progression of all CVD, and such CVD positivity metrics may be helpful in tracking disease progression and treatment efficacy. As the fields of aging and dementia research consider multiple targets for preventing cognitive decline, CVD positivity metrics can be used to also summarize vascular burden into a single metric.

Limitations

The present study included only those participants without dementia. The prevalence of dementia differs by age, and our estimates of CVD imaging burden are affected negligibly in the segment of our study group younger than 70 years. At ages greater than 70 years, the rising prevalence of dementia, coupled with the likely higher burden of CVD pathologic change, probably indicates that we have underestimated the prevalence of the CVD imaging lesions in the older groups. We did not assess other characteristics, such as perivascular spaces or intracranial vessel disease, because T2-weighted MRI scans and magnetic resonance angiograms were not available. In future attempts to create a unifying cerebrovascular biomarker, it may be important to evaluate these additional factors.

Conclusions:

CVD burden increases with age. Men tend to have more infarcts and CMBs while women tend to have more WMHs, at least until the eighth decade. The medical field places a greater emphasis on vascular disease prevention, earlier diagnosis, and treatment of risk factors. In light of this emphasis, the present study provides the ability to look at change prevalence over time across age and sex strata, as well as provide the framework to identify additional age- and sex-specific risk or protective factors in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01AG034676. In addition, it is supported by NIH Award Numbers R37AG011378, K76AG057015-02, R01AG041851, R01NS097495, and RF1AG55151. The study received support from the GHR Foundation. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or Gerald and Henrietta Rauenhorst. The funding sources had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Jonathan Graff-Radford, MD, had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Financial Support and Disclosure:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and the GHR Foundation. Dr. Graff-Radford reports grants from the National Institute on Aging. He receives funding from the Alzheimer’s Treatment and Research Institute. He received an honorarium from the American Academy of Neurology for serving as a guest editor of Continuum. Dr. Knopman serves on a data safety monitoring board for the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network study. He is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Eli Lilly Biogen, and the Alzheimer’s Treatment and Research Institute and receives research support from NIH. Dr. Schwarz reports grants from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Flemming reports grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, and Boston Scientific Corporation. Dr. Rabinstein receives royalties from Elsevier and Oxford University Press and has received research support from DJO Global, Inc. Dr. Petersen is a consultant for Roche Holding AG, Biogen, Merck & Co, Eli Lilly and Co, and Genentech. He receives publishing royalties from Mild Cognitive Impairment (Oxford University Press, 2003) and research support from NIH. Dr. Kantarci serves on the data safety monitoring board for Takeda Global Research & Development Center, Inc; receives research support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc, and Eli Lilly and Co; and receives funding from NIH and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. Dr. Huston reports patents from the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research and royalties from Resoundant, Inc, stock and receives stock options in Resoundant, Inc. He reports no competing financial interests to the present article. Dr. Jack consults for Eli Lilly and serves on an independent data monitoring board for Roche Holding AG. However, he receives no personal compensation from any commercial entity. He receives research support from the NIA of the NIH and the Alexander Family Professor of Alzheimer’s Dsease Research, Mayo Clinic. Dr. Mielke is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Co and Lysosomal Therapeutics, Inc. She receives unrestricted research grants from Biogen, Lundbeck, and Roche Holding AG and receives research funding from the NIA of the NIH and the US Department of Defense. Dr. Vemuri reports grants from the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The other authors report no disclosures.

Abbreviations

- CMB

cerebral microbleed

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CVD

cerebrovascular disease

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- GRE

gradient recalled echo

- MCSA

Mayo Clinic Study of Aging

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- WMH

white matter hyperintensity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(9):934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero JR, Preis SR, Beiser A, et al. Risk factors, stroke prevention treatments, and prevalence of cerebral microbleeds in the Framingham Heart Study. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1492–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poels MM, Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: an update of the Rotterdam scan study. Stroke. 2010;41(10 Suppl):S103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Wen W, Anstey KJ, Sachdev PS. Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors of lacunar infarcts in a community sample. Neurology. 2009;73(4):266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sveinbjornsdottir S, Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, et al. Cerebral microbleeds in the population based AGES-Reykjavik study: prevalence and location. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(9):1002–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins RO, Beck CJ, Burnett DL, Weaver LK, Victoroff J, Bigler ED. Prevalence of white matter hyperintensities in a young healthy population. J Neuroimaging. 2006;16(3):243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeCarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, et al. Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the framingham heart study: establishing what is normal. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(4):491–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeer SE, Koudstaal PJ, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Prevalence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2002;33(1):21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Vermeer SE, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Frequency of white matter lesions and silent lacunar infarcts. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2002. 62):25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Achten E, et al. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam Scan Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(1):9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price TR, Manolio TA, Kronmal RA, et al. Silent brain infarction on magnetic resonance imaging and neurological abnormalities in community-dwelling older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke. 1997;28(6):1158–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao D, Cooper L, Cai J, et al. Presence and severity of cerebral white matter lesions and hypertension, its treatment, and its control. The ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Stroke. 1996;27(12):2262–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30(1):58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raz L, Jayachandran M, Tosakulwong N, et al. Thrombogenic microvesicles and white matter hyperintensities in postmenopausal women. Neurology. 2013;80(10):911–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite Mixture Models. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graff-Radford J, Botha H, Rabinstein AA, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: Prevalence and relationship to amyloid burden. Neurology. 2019;92(3):e253–e262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braffman BH, Zimmerman RA, Trojanowski JQ, Gonatas NK, Hickey WF, Schlaepfer WW. Brain MR: pathologic correlation with gross and histopathology. 1. Lacunar infarction and Virchow-Robin spaces. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bokura H, Kobayashi S, Yamaguchi S. Distinguishing silent lacunar infarction from enlarged Virchow-Robin spaces: a magnetic resonance imaging and pathological study. J Neurol. 1998;245(2):116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jungreis CA, Kanal E, Hirsch WL, Martinez AJ, Moossy J. Normal perivascular spaces mimicking lacunar infarction: MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;169(1):101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Syrjanen JA, et al. Weighting and standardization of frequencies to determine prevalence of AD imaging biomarkers. Neurology. 2017;89(20):2039–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Little RJ, Groves RM. Advances in strategies for minimizing and adjusting for survey nonresponse. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17(1):192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, et al. Vascular and amyloid pathologies are independent predictors of cognitive decline in normal elderly. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 3):761–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staals J, Booth T, Morris Z, et al. Total MRI load of cerebral small vessel disease and cognitive ability in older people. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(10):2806–2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barker-Collo S, Bennett DA, Krishnamurthi RV, et al. Sex Differences in Stroke Incidence, Prevalence, Mortality and Disability-Adjusted Life Years: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45(3):203–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Leys D, et al. A semiquantative rating scale for the assessment of signal hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Sci. 1993;114(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeerakathil T, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2004;35(8):1857–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fatemi F, Kantarci K, Graff-Radford J, et al. Sex differences in cerebrovascular pathologies on FLAIR in cognitively unimpaired elderly. Neurology. 2018;90(6):e466–e473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, including data from this study, are available upon request.