Abstract

Full understanding of the catalytic action of non-heme iron (NHFe) and non-heme diiron (NHFe2) enzymes is still beyond the grasp of contemporary computational and experimental techniques. Many of these enzymes exhibit fascinating chemo-, regio- and stereoselectivity, in spite of employing highly reactive intermediates which are necessary for activations of most stable chemical bonds. Herein, we study in detail one intriguing representative of the NHFe2 family of enzymes: soluble Δ9 desaturase (Δ9 D) which desaturates rather than performing the thermodynamically favorable hydroxylation of substrate. Its catalytic mechanism has been explored in great detail by using QM(DFT)/MM and multireference wave function methods. Starting from the spectroscopically-observed 1,2-μ-peroxo diferric P intermediate, the proton-electron uptake by the P is the favored mechanism for catalytic activation since it allows a significant reduction of the barrier of the initial (and rate-determining) H-atom abstraction from the stearoyl substrate as compared to the ‘proton-only activated’ pathway. Also, we ruled out that a ‘Q-like intermediate’ (high-valent diamond-core bis-μ-oxo-[FeIV]2 unit) is involved in the reaction mechanism. Our mechanistic picture is consistent with the experimental data available for Δ9D and satisfy fairly stringent conditions required by Nature: the chemo-, stereo- and regioselectivity of the desaturation of stearic acid. Finally, the mechanisms evaluated are placed into a broader context of NHFe2 chemistry provided by an amino acid sequence analysis through the families of the NHFe2 enzymes. Our study thus represents an important contribution toward understanding the catalytic action of the NHFe2 enzymes and may inspire further work in NHFe(2) biomimetic chemistry.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last decades, mononuclear and binuclear non-heme iron enzymes (NHFe and NHFe2) have raised considerable interest owing to their versatility in catalyzing a multitude of essential biochemical transformations, such as functionalization of the C–H bonds of alkyl chains and aromatic rings, heterocyclic ring opening and formation, epoxidation, or the C–C bond desaturation.1,2 Most of the NHFe2 enzymes share a common structural motif comprising a four-helix bundle protein fold that accommodates two iron ions, which are coordinated by two histidine and four glutamate residues to form the active site. This implies that NHFe2 may also share specific reaction patterns such as the activation of the resting state of an enzyme via the addition of O2 (or resting state via H2O2), leading to more reactive oxygenated intermediates (vide infra).

Still, geometric and electronic structure properties of NHFe2 intermediates and their contributions to reactivity remain largely underexplored. From a theoretical perspective, the NHFe2 enzymes belong to one of the most difficult systems to study computationally3,4 due to strong correlation effects given by the multireference character of many of their electronic states5,6,7,8 which often precludes the straightforward usage of standard density functional theory (DFT). Instead, multireference ab initio wave-function methods need to be applied. However, their application is far from routine and deep understanding of the many subtleties in a particular computational protocol limits their widespread practice.3,4,9 Despite the above drawbacks, considerable advances in understanding NHFe2 were made by correlating quantum chemical calculations with experimental – mostly spectroscopic – data.2,10

Δ 9 Desaturase (Δ9D, EC 1.14.19.2., Pfam ID PF03405) is an O2-dependent binuclear non-heme iron enzyme that evolved to convert stearic acid to oleic acid as a part of the fatty-acid metabolic pathway of plants.11,12,13,14 The process, which is highly chemo-, regio-, and stereoselective, involves a cis double bond insertion into a C9–C10 bond of a stearic acid via two sequential H-atom abstraction (HAA) reactions. Prior to an initial C10–H bond activation,15 preparatory stages in Δ9D catalytic cycle include: (i) substrate binding within the active site pocket, which perturbs ligation coordination spheres of both Fe centers from penta,penta (5C,5C) to penta,tetra (5C,4C) coordination and thus increases the affinity of the active site for O2 binding;16,17 (ii) O2 activation yielding the experimentally observed peroxo-diferric P intermediate (cf. Figure 1);18 (iii) conversion of the non-reactive P into an intermediate capable of the initial HAA from the stearic acid.19

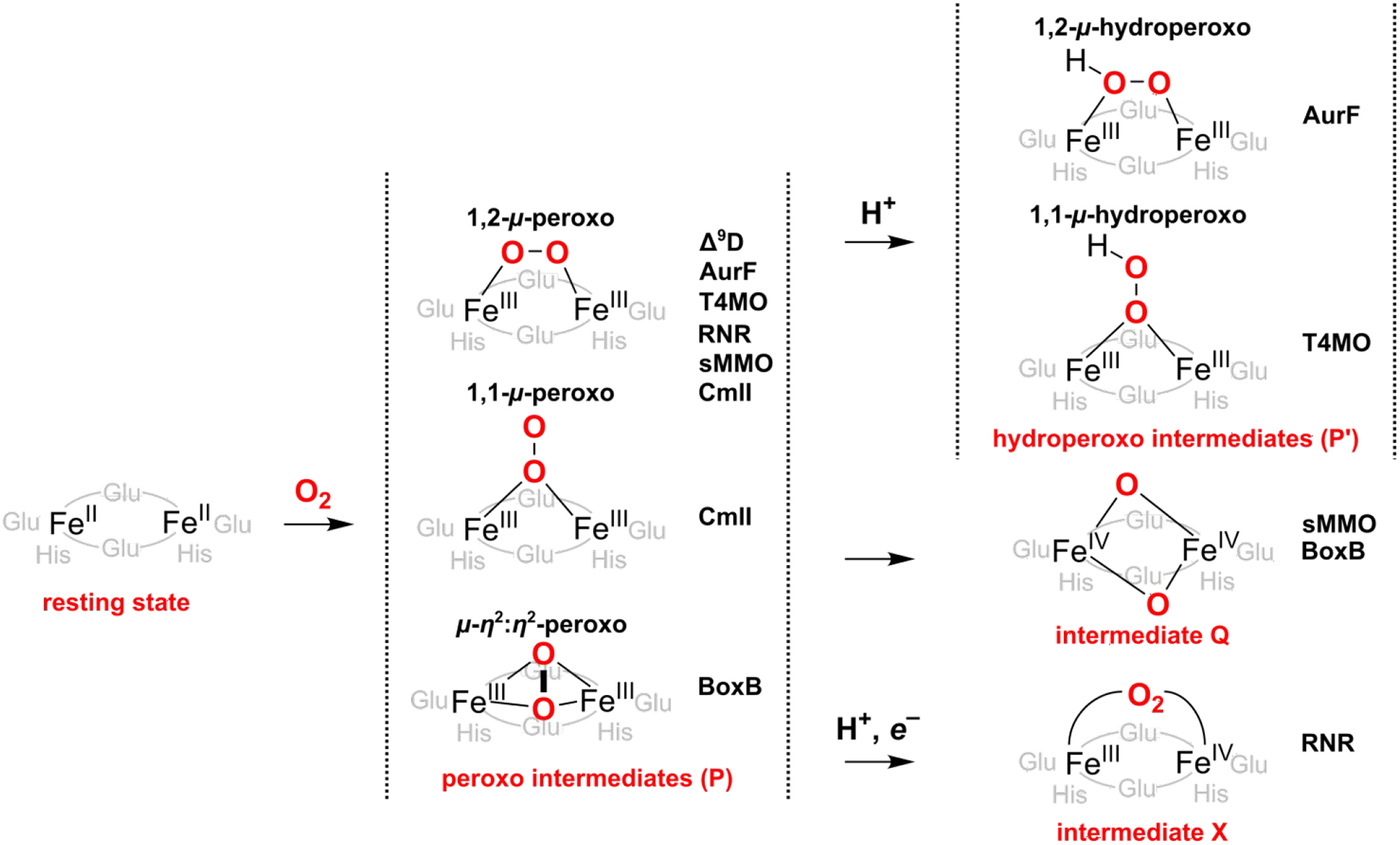

Figure 1.

Proposed oxygenated intermediates of selected NHFe2 enzymes. Δ9D = Δ9 desaturase; sMMO = soluble methane monooxygenase; BoxB = benzoyl coenzyme A epoxidase; AurF = p-aminobenzoate N-oxygenase; T4MO = toluene 4-monooxygenase; Rbr = rubrerythrin; RNR = ribonucleotide reductase; CmlI = arylamine oxygenase.

A range of HAA reactive intermediates has been previously suggested for Δ9D or other NHFe2 enzymes (examples are given in Figure 1).18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 However, none of these has been experimentally captured and characterized for Δ9D. This contrasts for example soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO), where the FeIIIFeIII P intermediate converts to the high-valent (FeIVFeIV) intermediate Q,28,29,30 or to the R2 subunit of class I ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), where the peroxo moiety P is proposed to be first protonated to yield a 1,2-μ-hydroperoxo FeIIIFeIII P’ that accepts an exogenous electron leading to a mixed-valence FeIVFeIII intermediate X31,32,33,34,35,36.

Herein, we build on a detailed investigation of initial stages of O2 activation in the Δ9D active site reported earlier by our group18,19 and explore several reaction pathways in order to complete the catalytic cycle. To this aim, we employ the hybrid DFT/molecular mechanics (DFT/MM) calculations, which we complement for key reaction steps by using advanced multiconfigurational/multireference methods such as multireference configuration interaction, MRCI;37,38 complete active space second-order perturbation theory, CASPT2;39,40,41 and multiconfiguration pair-density functional theory, MC-PDFT42,43. As revealed in this study, several possible activations of P, including proton-assisted, O–O cleavage, and proton-electron transfer (PET)-assisted pathways may all represent viable alternatives of the Δ9D reaction mechanism. Our calculations tend to favor the PET-assisted activation of the P. Additionally, computed data and postulated proton and electron transfer pathways for the PET-assisted mechanism of P activation are further corroborated by the extensive bioinformatics study of various NHFe2 enzymes as well as different plant, archaeal, and bacterial desaturases.

2. COMPUTATIONAL DETAILS

2.1. Protein Setup.

All reported calculations are based on the fully equilibrated all-atom QM/MM model built from the crystal structure of Δ9 stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase obtained at the resolution of 2.4 Å (Protein Data Bank accession code 1AFR).44 Because of the absence of the X-ray structure of the [protein…substrate] complex, a simplified substrate model (i.e., CH3-(CH2)16-COO-phosphopantetheine linker capped by a methyl group instead of an acyl carrier protein) was docked manually into the substrate entrance channel of the Δ9D in our previous study.19 In this work, a position of the substrate in the Δ9D active site was further refined - employing the newly published X-ray structure with the resolution of 3.35 Å (PDB code 2XZ1)45 - by simulated annealing of eight different initial substrate conformations, and the QM region was expanded by including amino acids in higher coordination spheres of the two iron ions (see Figure S1). The system preparation for the QM/MM calculations were described in detail in Ref. 18 and was followed accordingly in the presented study (see the Supporting Information).

2.2. QM/MM Calculations.

The ComQum software46,47 was used for all QM/MM calculations. Within the QM/MM approach, the entire system was divided into three regions as follows: (i) System 1 (flexible region; treated at the QM level); (ii) System 2 (flexible region; treated at the MM level); (iii) System 3 (fixed region; MM level). System 1 comprised the active site of an enzyme, corresponding to 196 or 197 atoms (based on the protonation of the peroxo bridge − vide infra). The flexible MM region (System 2) consisted of all residues and water molecules within 3 Å of any atom in System 1, truncated at the ‘per-residue’ level (resulting in 48 amino acids + 2 water molecules), and the fixed region (System 3) comprised of the remaining part of the protein and the solvent water molecules (643 amino acids + 6980 water molecules in total). Within the QM(DFT) calculations, the atoms specified as part of System 1 were treated quantum chemically. System 1 has been polarized by atoms in System 2 and System 3 – represented by point charges – i.e., the electrostatic embedding scheme in the QM/MM terminology. A junction between Systems 1 and 2 was modeled utilizing the hydrogen link-atom approach.48 A detailed description of the contributions to the total QM/MM energy as well as many technical details on the ComQum software can be found elsewhere.46,47,49 In brief, the total (QM/MM) energy is calculated as:

| (1) |

where EQM-pchg corresponds to the QM energy of System 1 embedded in a set of point charges of the System 2 and 3 (MM part), EMM123 is the MM energy of the entire system, and EMM1 is the MM energy of System 1 with MM charges of the System 1 zeroed.

All DFT calculations (QM region) were performed using the Turbomole 6.6 program.50 Geometry optimizations were carried out using the TPSS functional51 with the def2-SV(P) basis set,52 including the empirical zero-damping dispersion correction (D3)53, and expedited by the RI-J approximation.54 The S = 0 (or S = 1/2 in the 1e−-reduced system) spin state with the antiferromagnetically-coupled iron ions in the high-spin states (S = 5/2 for FeIII or S = 2 for FeIV) was considered throughout. The transition states were obtained as one- or two-dimensional scans of QM/MM potential energy surfaces (PESs). The MM calculations were performed employing the Amber ff14SB force field.55

2.3. Single-point QM Calculations.

On top of QM(TPSS-D3/def2-SV(P))/MM equilibrium geometries, the EQM-pchg term is evaluated with B3LYP*-D3 method (i.e., where the symbol “*” refers to B3LYP-D3 with 15 % of Hartree-Fock exchange)56 employing the def2-TZVP basis set52; the method is denoted in the text as: QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM.

As implemented in the MOLCAS 8.2 program,57,58,59,60 multiconfigurational/multireference approximations to wave function theory (WFT) such as the CASSCF,61,62 CASPT2,39,40,41 and MC-PDFT42,43 methods were applied in the combination with the ANO-RCC63,64 basis set to size-reduced model systems (86–87 atoms, cf. Figure 2) as prepared from the QM/MM equilibrium geometries. The ANO-RCC basis set, contracted to [6s5p3d2f1g] for Fe, [4s3p2d] for ligating N and O atoms, [3s2p] for C and non-ligating N atoms, and [2s] for H atoms, was used. The second-order Douglas−Kroll−Hess (DKH2)65,66,67 one-electron spin-less Hamiltonian was applied for all of the WFT-based calculations to allow for spin-free relativistic effects. In all CASSCF calculations, a level shift of 5 a.u. was used to improve convergence. The Cholesky decomposition technique68 with a threshold of 10−6 a.u. was used to approximate two-electron integrals. Complete active spaces used in CASSCF calculations are specified in the text and comprise up to 22 electrons in 18 orbitals (see Figure S2). To account for the absence of dynamical correlation in the CASSCF method, the CASPT2 and MC-PDFT energies were also evaluated (for MC-PDFT, the ftBLYP, ftPBE, ftrevPBE, tBLYP, tPBE and trevPBE functionals were employed)69. For these WFT-based calculations, the total ‘QM/MM energy’ was then evaluated as:

| (2) |

where EWFT,Model is the energy calculated for the size-reduced model in vacuo using the CASSCF, CASPT2 or MC-PDFT method, EDFT,FullQM is the energy calculated for the full QM system (with electrostatic embedding) at the DFT level (with the B3LYP* functional), and EDFT,Model is the B3LYP* energy calculated on the size-reduced model in vacuo. The last two terms in Eq. (2) are the same as in Eq. (1).

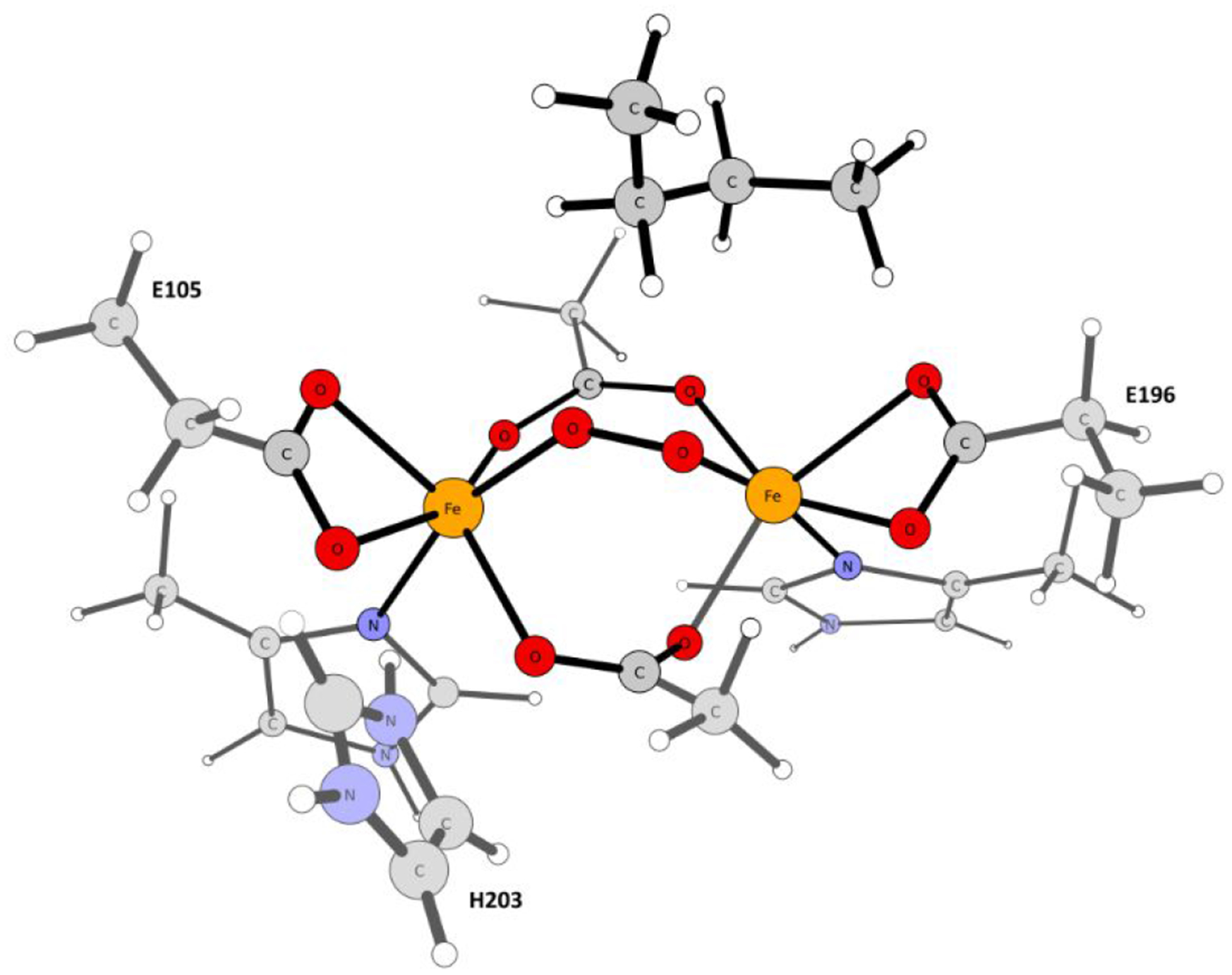

Figure 2.

Truncated cluster model of the Δ9D active site utilized in the WFT calculations.

2.4. Calculations of Reduction Potentials.

To compare pathways differing by the number of electrons involved (ΔNel = 1), the 1e−-reduction potentials were approximated according to:

| (3) |

where Eoxidized and Ereduced are the potential energies of oxidized and reduced states of the solute/enzyme (i.e., without taking into account the thermal enthalpic and entropic contributions), and E°abs(reference) is the absolute potential of a reference electrode. Herein, we adopted the values of E°abs(reference) = 4.34 eV for SHE in water70 and 5.04 eV for ferrocenium/ferrocene couple in acetonitrile71 (note that to be consistent with the level of calculations, these reference values do not include the ionization threshold energy of a free electron, i.e., neglecting the electron entropy).72

As for enzymatic intermediates, the potential energies were obtained at the equilibrium geometries of the oxidized and reduced states at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level of theory as indicated above. The small binuclear iron complexes were correspondingly optimized using TPSS-D3/def2-SV(P) method with the COSMO solvation model73 accounting for solvation in acetonitrile, and the energies were then obtained from single-point calculations using B3LYP*-D3/def2-TZVP with the COSMO-RS solvation model.74,75

2.5. Sequence Analysis.

Sequences of different plant, archaeal, and bacterial desaturases were obtained by the NCBI BLAST76 search, performed by employing the amino acid sequence of the Ricinus communis Δ9D, i.e., the one used in the QM/MM study. Randomly chosen sequences from different genera with annotated ACP-desaturase with decreasing sequence identity to Ricinus communis (92 – 26 %) were considered. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the Clustal Omega algorithm.77,78 Sequences and structures of different NHFE2 enzymes were taken from the following crystal structures (PDB IDs): 1MHY (soluble methane monooxygenase; sMMO),79 3PM5 (benzoyl coenzyme A epoxidase; BoxB),80 1CHT (p-aminobenzoate N-oxygenase; AurF),81 3DHH (toluene 4-monooxygenase; T4MO),82 1RYT (rubrerythrin; Rbr),83 and 1MXR (ribonucleotide reductase; RNR)84. Structure-driven sequence alignment was performed using the PROMALS3D algorithm.85

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Plausible Activation Pathways of the P Intermediate.

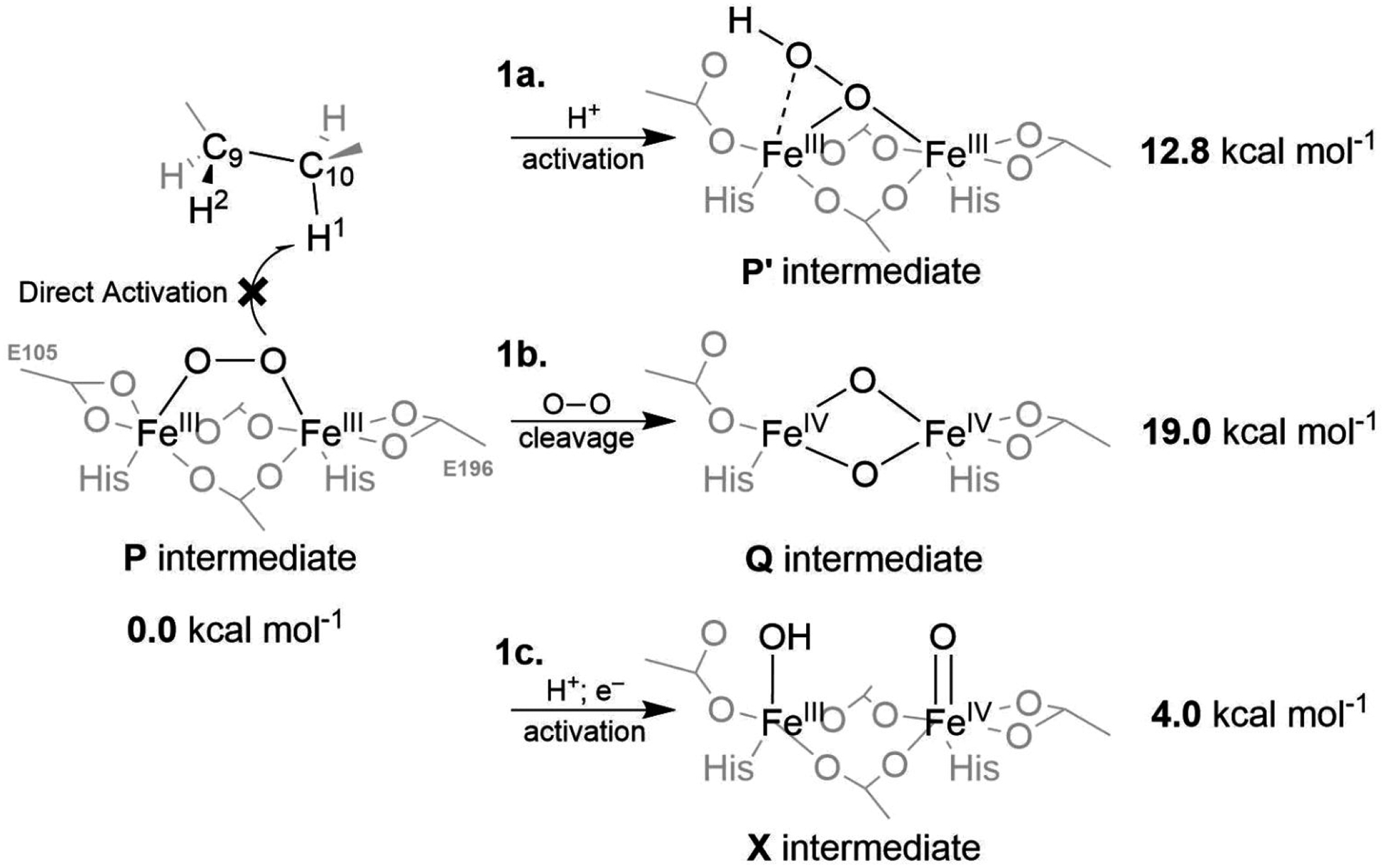

The P intermediate is best described as the 1,2-μ-peroxo-[FeIII]2 complex (Figure 3; left) with a (6C,6C) or (5C,6C) coordination.18 The (6C,6C) model is energetically favored, while the (5C,6C) model with a monodentate binding mode of Glu196 is more consistent with available spectroscopic data.18 The direct attack on the substrate’s C10–H bond by P is, however, unlikely, as the lowest TS barrier is calculated to be ~25 kcal mol−1, with respect to the P intermediate (see Table S1). This is in disagreement with the barrier (activation energy) of ~15 kcal mol−1, derived from kinetic measurements.86 Thus, we explore the possibility of three alternative pathways for P activation, denoted as 1a, 1b, and 1c in Figure 3. Pathway 1a involves protonation of the peroxo unit, leading to a μ-η2:η1-hydroperoxo-[FeIII]2 species (denoted as P’) that was already proposed in ref. 19; 1b involves the O–O bond cleavage to yield the bis-μ-oxo-[FeIV]2 complex, which is thought to exist as intermediate Q in the sMMO enzyme,28,29,30 and 1c corresponds to the P activation by concomitant H+/e− transfers into the active site.

Figure 3.

The spectroscopically observed 1,2-μ-peroxo-[FeIII]2 intermediate P is inactive toward the C–H bond cleavage. Thus, several activation pathways are proposed: (i) the proton-assisted rearrangement producing the μ-η2:η1-hydroperoxo-[FeIII]2 species P’ (1a), (ii) the O–O bond cleavage to yield the bis-μ-oxo-[FeIV]2 complex putatively corresponding to the intermediate Q in sMMO (1b), and (iii) concomitant proton and electron transfers to yield the complex, which would be reminiscent of the intermediate X of the Class Ia RNR enzyme (1c). The energies are calculated at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level of theory and referenced to the energy of the P intermediate.

3.2. Proton Transfer (PT)-Assisted Activation of the P Intermediate.

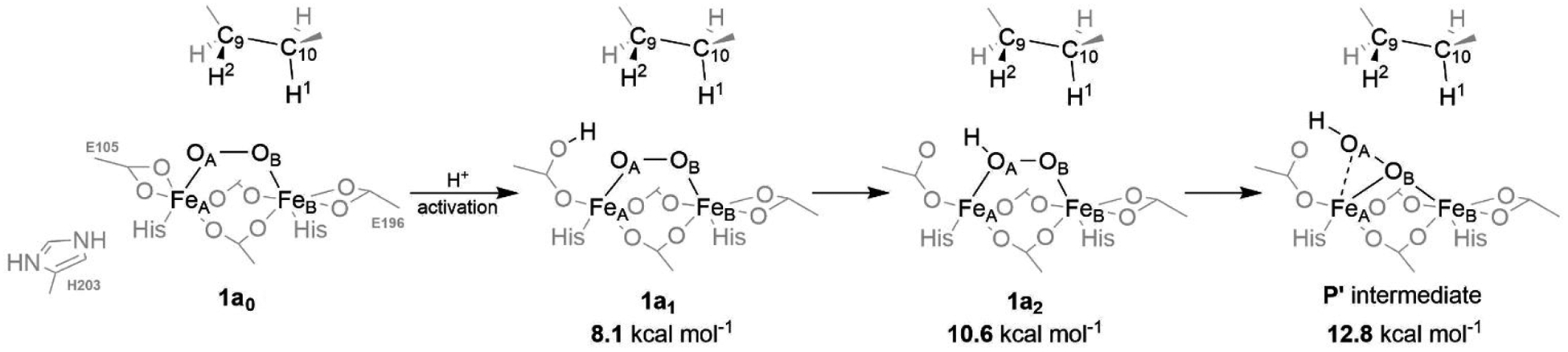

Proton transfer from the second-shell His203 residue to the FeA-terminal Glu105 ligand triggers a considerable change in the coordination sphere of the FeA center, opening an energetically accessible protonation of the bridging peroxo group (Figure 4). This results in the formation of the μ-η2:η1-hydroperoxo-[FeIII]2 intermediate P’, which is ~13 kcal mol−1 above P. To probe reactivity of P’ with respect to HAA from the C10–H bond, we performed a relaxed scan along the OA…H1 coordinate yielding a ‘TS’ that is depicted in Figure 5, center (note that key geometrical parameters for reaction intermediates of all reaction pathways are illustrated in Figure S3). At this TS, the O–O distance is 0.22 Å longer than in P’, while spin density remains essentially unchanged, indicating no electron transfer from the substrate to the diiron center (cf. pathway 1a in Table S2).

Figure 4.

A possible pathway for the protonation of the active site of the P intermediate. The energies are calculated at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level of theory and referenced to the energy of the P intermediate. Note that 1a0 structure is already protonated at the His203 residue and, therefore, does not correspond to the referential P intermediate from Figure 3.

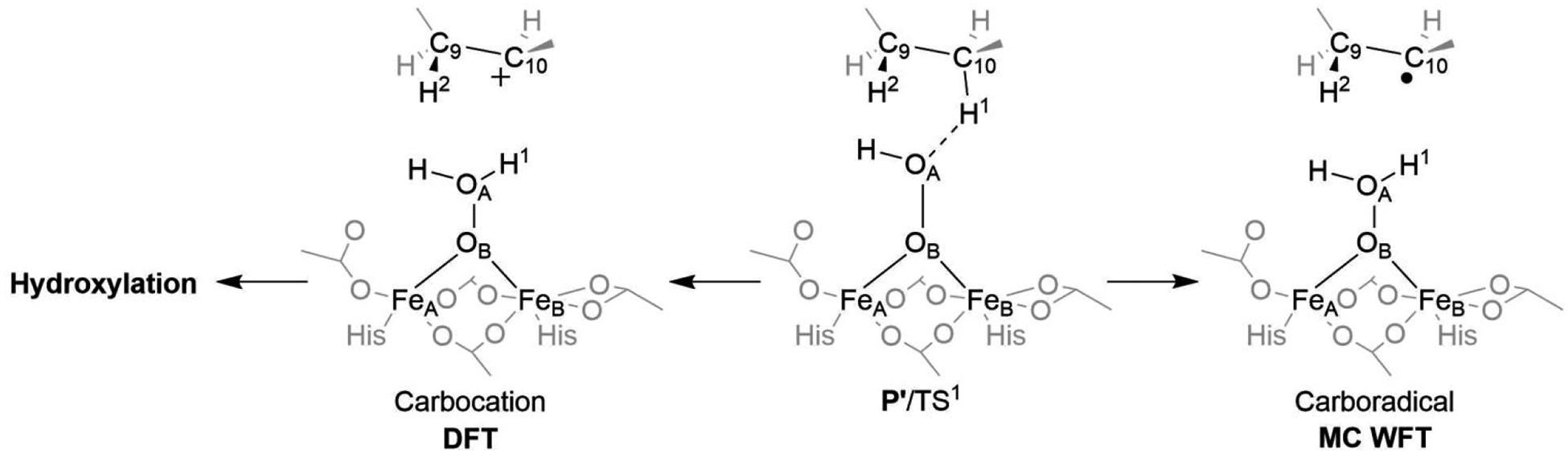

Figure 5.

A different character of the TS for C10–H bond cleavage is observed for the DFT calculations (heterolytic cleavage; Left) and multiconfigurational WFT-based methods (homolytic cleavage; Right).

The QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM activation energy of ~33 kcal mol−1 (referenced to the P intermediate), seems to be significantly overestimated as compared to the barriers obtained using multiconfigurational methods. According to the CASPT2- and MC-PDFT-based QM/MM calculations (with the active space of 14e,14o)†, the barrier along the reaction coordinate from the P to the TS for C10–H bond cleavage is predicted to lie between 21 and 25 kcal mol−1. However, this is still too high in the comparison to the experimentally-derived energy of activation of ~15 kcal mol−1.86 We note in passing that C10–H bond activation is inaccessible also from the 1,2-μ-hydroperoxo-[FeIII]2 intermediate 1a2 (depicted in Figure 4) as the barrier exceeds 30 kcal mol−1.

It is also notable that DFT and the multiconfigurational methods differ in the description of the mechanism of the C10–H bond cleavage (Figure 5). DFT favors heterolytic cleavage producing a carbocationic substrate intermediate, whereas WFT methods prefer homolytic cleavage, as discussed already in ref. 19. We have investigated this aspect in more detail in this study and found that near the P’/TS structure (representing the ‘bifurcation’ point), MC-PDFT and MRCI87 methods predict the carbocationic electronic structure as high-lying excited state (favoring carboradical by tens of kcal.mol−1), in contrast to most DFT functionals.

While the ‘absolute’ accuracy of computed values for the NHFe/NHFe2 sites can be a matter of debate, it is clear that the mechanism of the first substrate’s C–H bond activation is critical for enzymatic selectivity. When the carbocation is formed, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to avoid the energetically most favorable local minimum, which is a hydroxylated alkyl chain. The subsequent dehydration process that would yield the final desaturated product is not energetically feasible (the process is associated with a calculated activation barrier of > 65 kcal mol−1). Thus, the C10–H bond heterolysis seems to represent a ‘thermodynamic trap’, suggesting that the enzyme following the 1a pathway would have to undergo a carboradical formation instead to yield a product of desaturation. Following the ‘substrate-radical’ mechanism, desaturation is accomplished by the barrierless cleavage of the second C9–H bond, providing the oleic acid as a final product.

3.3. Splitting the O–O Bond in the P intermediate.

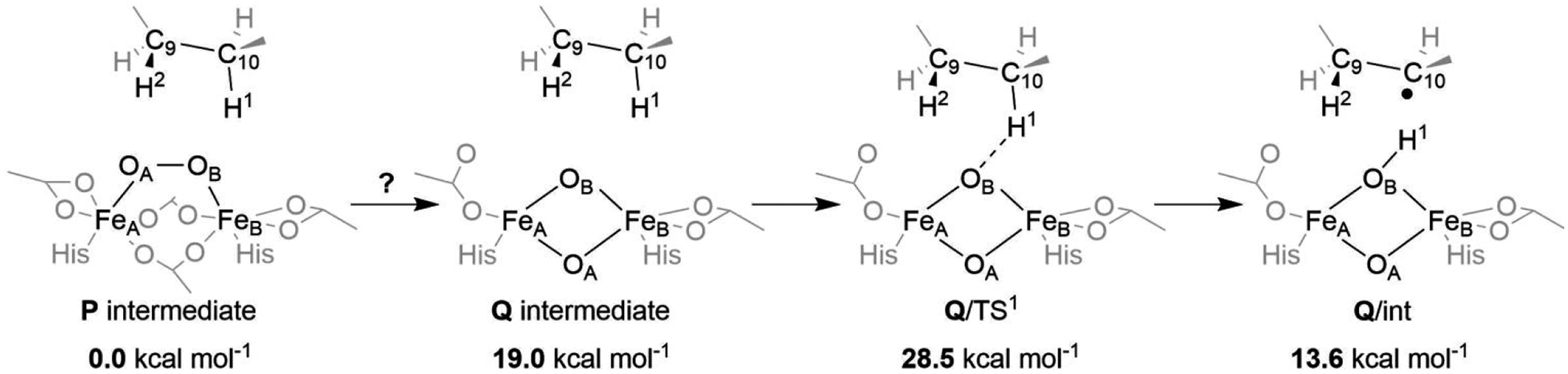

The so-called Q intermediate is a key reactive species in the catalytic cycle of the binuclear non-heme iron soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO).29,30,88 It has been postulated to adopt the Fe2O2 diamond core geometry with two antiferromagnetically coupled high-spin (S = 2) FeIV centers bridged by two oxo groups, yielding a total spin state of S = 0 (note that also other geometries of Q were recently proposed in the literature)89. Herein, an analogous Q-like diamond core was investigated employing our QM/MM model of Δ9D. At the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level, the Δ9D Q is ~19 kcal mol−1 higher in energy than the P intermediate. Nevertheless, a somewhat smaller energy barrier of ~10 and 12–19 kcal mol−1 was obtained from the CASPT2- and MC-PDFT-based QM/MM calculations, respectively (for MC-PDFT, the range of energies reflects usage of six different functionals on top of the (20e,16o)‡ CASSCF reference wave function). We note in passing that understabilization of the Q-like intermediate at the B3LYP level was already recognized in the computational studies of the sMMO90 as well as the BoxB27 enzymes.

With respect to C10–H bond activation by Δ9D Q (Figure 6), the TS character is very different from that calculated for P’. Compared to P’, the TS is considerably later as evidenced by: (i) a shorter O…H1 bond length (1.31 vs. 1.20 Å for P’/TS1 vs. Q’/TS1), and (ii) a spin density at the C10 site indicating that carboradical character was already developed at the TS (cf. Table S2). This suggests a ‘carboradical’ channel is operative, effectively preventing the hydroxylation of the natural substrate.

Figure 6.

Activation of the C10–H bond by the Q intermediate. The energies are calculated at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level of theory and referenced to the energy of the P intermediate.

However, the barrier for C10–H bond activation is exceedingly high (29, 35–40, and 23 kcal mol−1 relative to P as calculated using QM/MM scheme with the respective QM level of theory: B3LYP*-D3, MC-PDFT, and CASPT2§). Comparing the lowest estimate of the barrier as obtained at the QM(CASPT2)/MM level of theory with the experimentally inferred value of ~15 kcal mol−1, we do not consider the Q-involved 1b pathway to be mechanistically relevant in the Δ9D with the native substrate.

3.4. Proton-Electron Transfer (PET)-Assisted Activation.

3.4.1. Energetics.

The concurrent protonation and one-electron reduction of the active site is a frequently adopted mechanism for activation of enzymes for catalysis, thus avoiding very ‘high-energy’ intermediates.91,92,93,94 Herein, we explore the possibility of 1e− reduction of the active site upon its protonation by evaluating reduction potentials of all key reaction intermediates along the 1a coordinate (Table 1). As can be seen in Table 1, the reduction potential (E°) of a non-protonated P intermediate is estimated to be very low (ca. −3.5 V vs. SHE), while all PT-activated forms have much less negative E° (ca. +3 V with respect to the E° of P). This suggests that the activation of P by electron transfer (ET) into the active site or by stepwise electron / proton transfers (ET/PT) is unlikely. Instead, either concerted proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) or stepwise proton transfer / electron transfer (PT/ET) mechanism can be considered as a possible activation process. For calibration, we calculated the E°’s of three synthetic binuclear oxo-bridged FeIVFeIV/FeIVFeIII redox couples using the same methodology as for Δ9D, which are presented along with the intermediates from the 1a pathway in Table 1. From this calibration, the accuracy of calculated reduction potentials in Δ9D is within ~0.5 V.

Table 1.

Calculated reduction potentials of intermediates from the pathway 1a from Figure 3, X intermediate from Figure 7, and synthetic binuclear complexes from refs. 96 and 97.

| Calcd. Eo [V] vs. SHE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| P | −3.48 | ||

| 1a1 | −0.75 | ||

| P’-(5C,6C) | −0.31 | ||

| P’-(6C,6C) | −0.44 | ||

| X | −3.00 | ||

| Calcd. Eo [V] vs. Fc+/0 | Expt. Eo [V] | Ref. | |

| [FeIV2O(L)2]2+/[FeIVFeIIIO(L)2]2+ | 1.21 | 1.50 | complex 1 in ref. 96 |

| [FeIV2(μ-O)2(La)2]4+/[FeIVFeIII (μ-O)2(La)2]3+ | 0.55 | 0.90 | complex 2a in ref. 97 |

| [FeIV2(μ-O)2(Lb)2]4+/[FeIVFeIII (μ-O)2(Lb)2]3+ | 0.31 | 0.76 | complex 2b in ref. 97 |

SHE = standard hydrogen electrode (referenced in water); Fc+/0 = ferrocenium/ferrocene couple (referenced in MeCN)

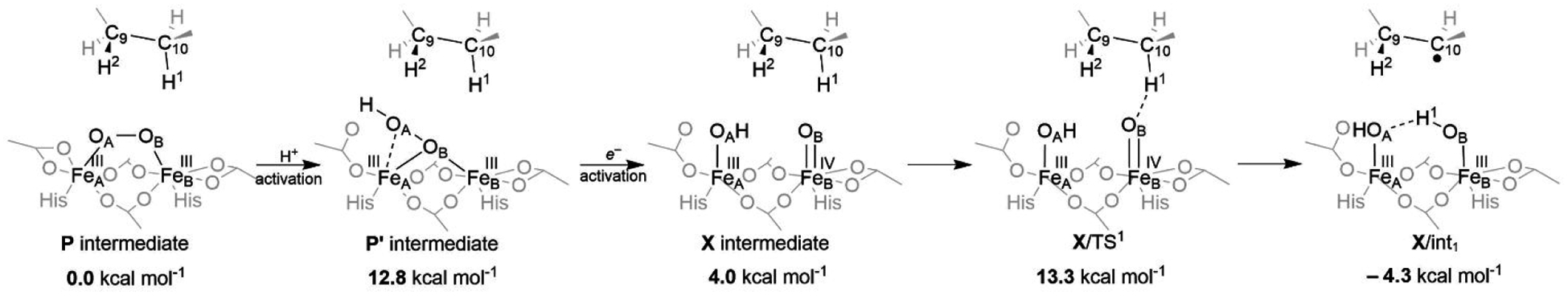

Ferredoxin (Fd) is the most probable source of an electron for the possible reduction of the protonated active site, as it is already involved in the regeneration of the Δ9D after completing the catalytic cycle for desaturation of the oleic acid. Injection of one electron into P’ from Fd should be feasible without a significant thermodynamic penalty as the E° of P’ (−0.31 V in Table 1) falls close to the range of E°’s of various plant-type [2Fe-2S] Fds (between −0.39 and −0.43 V vs. SHE at 25 °C).95 Importantly, ET to P’ triggers spontaneous O–O bond cleavage, yielding a mixed-valence FeIIIFeIV intermediate, which is analogous to the intermediate X in RNR (1c pathway; see Figure 3 and Figure 7). Importantly, this Δ9D ‘X’ is estimated to be only ~4 kcal mol−1 above P and its computed reduction potential of −3.0 V is also comparable to that of P (c.f., Table 1). Finally, the attack of C10–H bond by X is energetically accessible, with the barrier of 13, 14 or 15–17 kcal mol−1 as calculated by the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM, QM(CASPT2(15e,14o))/MM and QM(MC-PDFT(15e,14o))/MM approach, respectively. All these values are in agreement with the experimentally derived barrier of 14.8 kcal mol−1.86 As for the second substrate’s C9–H bond cleavage, which leads to the final desaturated product, the calculated barrier is significantly lower (~7 kcal mol−1 at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level). Thus, we consider PET-assisted activation of P (1c pathway in Figure 3), with two subsequent H-atom abstractions from the C10 and C9 sites of the substrate as the most viable catalytic mode of action in Δ9D.

Figure 7.

Plausible PET-assisted activation (stepwise PT/ET mechanism) of the P intermediate. Energies are calculated at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level of theory and referenced to the P intermediate. Note that coupled (concerted) proton-electron transfer might be a possible mechanism, bypassing the ‘high-energy’ P’ intermediate and converting P to X directly.

3.4.2. Desaturation vs. Hydroxylation Selectivity.

In contrast to P’, which is predicted by DFT to abstract hydride from the substrate C10 site that leads to carbocation (C10+) and hence hydroxylation trap, the X of the pathway 1c has already one extra electron and thus it has a lower oxidation power allowing only for HAA that produces carboradical-containing intermediate (X/int1 in Table 2). It is noteworthy that this intermediate is quite flexible and at least four other structural variants lie within ~7 kcal mol−1 (DFT) and therefore may be energetically feasible under turnover conditions. This flexibility is given by a variability in the coordination of the Glu105 and Glu196 residues and the orientation of the O–H bonds in the hydroxo ligands (Table 2).

Table 2.

Possible structures of the carboradical-containing intermediates in pathway 1c that are formed following the HAA step from C10 of the substrate. Energies are calculated using QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM and QM(MC-PDFT)/MM methods and referenced to the energy of the P intermediate. The range of energies for MC-PDFT method reflects usage of six different functionals. The structures are oriented so that the Glu105 and Glu196 residues are on the left and right side, respectively.

| QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM | QM(MC-PDFT)/MM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| X/int1 |  |

−4.3 kcal mol−1 | 2.6–5.5 kcal mol1 |

| X/int2 |  |

−1.8 kcal mol−1 | 6.8–11.7 kcal mo−−1 |

| X/int3 |  |

−0.3 kcal mol−1 | 0.1–2.8 kcal mol−1 |

| X/int4 |  |

1.7 kcal mol−1 | −1.1–3.0 kcal mol−1 |

| X/int5 |  |

2.9 kcal mol−1 | 3.2–8.4 kcal mol−1 |

Despite the presence of C10• (instead of C10+) in the intermediate X/int1 (Table 2), the OH rebound step is calculated to be nearly barrierless (at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level of theory), with the ‘C10•-to-FeB’ ET followed by the recombination of the nascent cation C10+ with the FeB-bound OH− ligand; the latter is strongly reminiscent of the pathway 1a from Figures 3 and 5. From the literature, the DFT barrier for the enzymatic mononuclear non-heme iron OH rebound is usually calculated to be in the range of 5–15 kcal mol−1.98,99,100,101 In this view, the QM/MM model (with the QM represented by DFT or a multireference wave-function calculation at the QM(DFT)/MM equilibrium geometries) seems to underestimate the barrier for hydroxylation from the X intermediate. As in pathway 1a, this is probably due to the considerable multireference character of the electronic structure of the binuclear non-heme iron species that cannot be accounted for by DFT and/or the inappropriate description of structural nuances preventing the “barrierless” hydroxylation. The significant discrepancy between the DFT and MC-PDFT energies of the five different carboradical-containing conformers (Table 2) precludes insights into how the hydroxylation trap is avoided in Δ9D.

The failure to describe properly the Δ9D chemo-selectivity by the QM/MM model reflects the fine-tuned ‘balance’ between desaturation and hydroxylation pathways (from numbers presented herein, we estimate the difference in the activation energies for the hydroxylation/desaturation to be not greater than ~2 kcal.mol−1). This is also evidenced by the observed oxygenation (hydroxylation) of some non-native substrates by wt and mutated forms of Δ9D.15,102,103 Here, we speculate that the role of non-native substrates such as fluorinated fatty acids and ether/thioether analogs of fatty acids is to promote the facile formation of the carbocationic intermediate that would effectively open the hydroxylation/oxygenation channels.

3.5. Proton and Electron Pathways Available for PET-assisted Activation of P; Comparison with Other Enzymes

3.5.1. Proton Pathways.

The activation of P by its protonation was proposed in some other NHFe2 enzymes, leading to a more reactive hydroperoxo species P’.2 For instance, the involvement of 1,2-μ-hydroperoxo-[FeIII]2 P’ was demonstrated to lower the kinetic barrier for the oxidation of 4-aminobenzoic acid in AurF by 8 kcal mol−1 due to the stabilization of a high-valent product of O–O bond cleavage.104Alternatively, the formation of P’ in RNR was also suggested to increase the reduction potential for further electron-transfer activation, resulting in a mixed-valence intermediate X (vide infra).21

It is worth mentioning that also the structure of the suggested Δ9D P’, i.e., the μ-η2:η1-hydroperoxo-[FeIII]2 (or energetically accessible 1,1-μ-hydroperoxo-[FeIII]2), is not unprecedented. The 1,1-μ-hydroperoxo P’ intermediate was captured by X-ray crystallography in T4MO Gln228Ala mutant.105 In T4MO, it was, however, proposed to be part of a non-productive pathway due to the overlay of the 1,1-μ-hydroperoxide with the C3 position of bound toluene substrate. Still, an observation of 1,1-μ-hydroperoxo species in the T4MO active site gives significant credence to our suggested model of the protonated P’ intermediate in Δ9D. Finally, it is also noticeable that the non-protonated μ-η2:η1-peroxo intermediate P in CmlI was suggested as the reactive species based on resonance Raman spectroscopy,106 and the 1,1-μ-peroxo P based on X-ray absorption spectroscopy107.

In our previous study of Δ9D, the PT activation of P was already suggested and a role of the second-shell His203 residue in the proton transfer chain via protonating the coordinated Glu105 was speculated.19 From the detailed bioinformatics analysis provided herein (Figure S4), we observe that His203 residue is conserved in plant as well as bacterial desaturases. In fact, two proton chains may thus connect the active site to the bulk solvent: (i) the previously proposed His203 – Asp101 – Thr206 – Cys222,18 or (ii) currently proposed His203 – Asp101 – Ser202 – Asp296 (see Figure S5). Although the Thr206 and Cys222 are often replaced by hydrophobic residues and Asp101 by Asn in many bacteria, the polar character of the latter proton chain is well conserved in plant and bacterial sequences and may facilitate proton transfer. If this is the case, similar proton chains should be present in other NHFe2 enzymes that are known to require proton transfer to activate P. Indeed, such polar chains can be located in e.g., T4MO and AurF (c.f., Figures S6 and S7). However, the polar residues are present in a different position suggesting that Nature has evolved a number of different ways to connect Fe-coordinated glutamate to the H-bonded network ending in the bulk solvent. In contrast, the proton transfer chain is replaced with apolar residues in sMMO and BoxB, for which a solvent-based protonation of the dioxygen cofactor is not required.

In addition, the role of Thr201 in toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase hydroxylase (ToMOH) was suggested to be essential for facilitating the proton transfer to the peroxo moiety in P and/or to stabilize the resulting reactive oxygenated intermediate.108 The equivalent residue, Thr199, is also present in Δ9D (c.f., Figure S8 for sequence alignment of various NHFe2 enzymes) and is conserved among all plant and bacterial desaturases. By mutating Thr199 for glutamic or aspartic acid, Shanklin and coworkers demonstrated a central role of Thr199 in the catalytic cycle due to the resultant decrease in desaturase activity (mutants reported peroxidase activity instead – in analogy to Rbr enzyme, where the same position is occupied by glutamic acid).109 Taken together, conserved Thr199 may facilitate protonation of P by the coordinated Glu105 via the conserved His203, which is connected to bulk solvent via a proton transfer chain.

3.5.2. Electron Pathways.

Although Fd is assumed to be the electron donor required for the pathway 1c, there might also exist other sources of electrons available for the reduction of the enzyme active site. The negatively-charged Fd was demonstrated to bind near Lys56, Lys60, and Lys230, so that the electrons are shuttled to the active site through the conserved Trp62 residue (c.f., Figure S8 for sequence alignment, Figure S9 for Trp62 position relative to the active site).110 On the other hand, the lysine residues are conserved only among plant desaturases, suggesting also the viability of an alternative electron-transfer chain. This may include, Trp132 – Trp135 – Trp139 – Tyr236 on the other side of the protein (Figure S9). Since counterparts of Trp135 and Trp139 were detected as radical donors upon mutation of the physiologically-relevant tyrosine to phenylalanine in RNR,111 these residues may indeed serve as a viable option for an alternative electron source for diiron site reduction in Δ9D or as a hole scavenger. However, there is no supporting experimental evidence that would clarify the role of this tryptophan chain. From the comparison to other NHFe2 enzymes, the activation of P’ by ET is appealing owing to the fact that only RNR (which requires ET to activate its P’ intermediate) contains some of aromatic residues, equivalent to those of Δ9D, capable of electron transfer.

We note in passing that also other similarities to RNR were found in our calculations. In RNR, the transfer of proton to 1,2-μ-peroxo diferric intermediate P is assumed to be responsible for stabilization of the peroxo σ* orbital, which upon electron activation leads to a reductive O–O bond cleavage, generating an intermediate X.21,112 Interestingly, such protonation was suggested to stabilize the peroxo σ* LUMO by as much as 2.38 eV.21 In Δ9D, we observed the same electron transfer-triggered O–O bond rupture that is associated with the increase in reduction potential upon protonation (in going from P to P’, the reduction potential increases by more than 3 V; cf. Table 1).

4. CONCLUSIONS

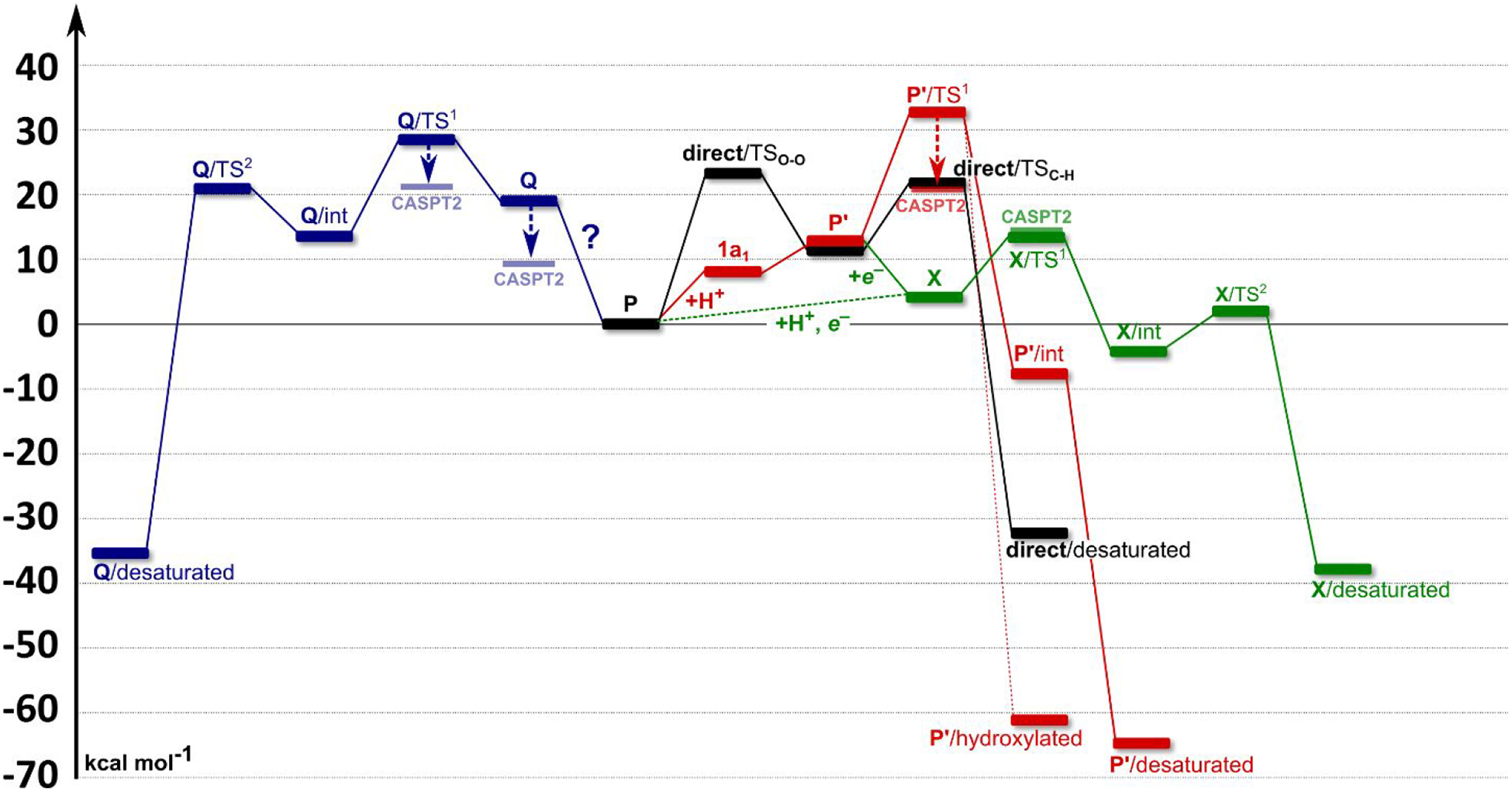

Employing the QM(DFT)/MM and multireference wave function methods, the catalytic mechanism of the non-heme binuclear Δ9 desaturase has been explored. Calculations suggest that the spectroscopically-observed P intermediate is not capable of the direct attack of the substrate (black in Figure 8). Therefore, we investigated three possible activation pathways of P and the following reaction steps leading to the desaturated product. The proton-electron uptake by the P intermediate (pathway 1c; in green in Figure 8) is the favored mechanism for catalytic activation since it allows a significant reduction of the barrier of the initial (and rate-determining) HAA from the stearoyl substrate as compared to the ‘proton-only activated’ pathway 1a and the O--O bond cleavage to generate a “Q” pathway 1b (in red and blue in Figure 8, respectively). This mechanistic picture is consistent with experimental data available for Δ9D and satisfy fairly stringent conditions required by Nature: the chemo-, stereo- and regioselectivity of the desaturation of stearic acid. Finally, all three studied mechanisms are placed into a broader context of NHFe2 chemistry provided by the amino acid sequence analysis through the families of the NHFe2 enzymes. In summary, this study represents an important advance in our understanding of the catalytic action of the NHFe2 enzymes and should inspire further work in the NHFe(2) biomimetic chemistry.

Figure 8.

The energetics associated with all of the studied pathways, calculated at the QM(B3LYP*-D3)/MM level of theory. Raw data are shown in Table S3. Black: A direct C10–H bond activation by P intermediate. First, the O–O bond of the P intermediate is cleaved with a calculated barrier of ~25 kcal mol−1 (the rate-determining step), followed by a C10–H bond activation (~22 kcal mol−1). Red: The proton-assisted activation pathway (1a). The protonation of P generates a P’ intermediate (12.8 kcal mol−1 above P), which may activate C10–H bond of a substrate. The barrier of ~33 kcal mol−1 is, however, too high to be operative. Blue: Cleavage of the peroxo O–O bond (pathway 1b). The ‘Q’ like [FeIV]2O2 intermediate is suggested to be inactive due to the rate-determining barrier of C10–H bond activation of ~29 kcal mol−1. Green: The activation of P by proton-electron uptake (1c). Here, either concerted or step-wise proton-electron transfer (dashed or solid line) is proposed, leading to a formation of an intermediate X analog (~4 kcal mol−1 above P). The energy of the rate-determining step within the 1c pathway (i.e., the C10–H bond cleavage) is consistent with the barrier derived from the experimental data (calcd. vs. expt.: ~13 kcal mol−1 vs. 14.8 kcal mol−1). The second C9–H bond is then activated with a small activation energy of ~7 kcal mol−1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The project was supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (18-13093S to M.S., 20-06451Y to J.C.), MSMT CR (LTAUSA19148, to L.R. and M.S.), National Institute of Health, U. S. A. (NIH 40392 to E.I.S.), and European Regional Development Fund; OP RDE (Project No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000729). Computer time at IT4I supercomputer center (project LM2015070 of the MSMT CR) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. All equilibrium geometries of QM systems in QM/MM or QM-only calculations, one full protein structure in PDB format (P intermediate), Tables S1-S3, Figures S1-S9. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

The (14e,14o) active space comprises all of the 3dFe-based molecular orbitals, σ and σ* orbitals of the O–O, and σ and σ* orbitals of the substrate C10−H1 bond.

The (20e,16o) active space comprises all of the 3dFe-based molecular orbitals, and all of the O2-originating valence orbitals.

The (22e,18o) active space comprises all of the 3dFe-based molecular orbitals, all of the O2-originating valence orbitals, and σ and σ* orbitals of the substrate C10−H1 bond.

REFERENCES

- (1).Krebs C; Bollinger JM; Booker SJ Cyanobacterial alkane biosynthesis further expands the catalytic repertoire of the ferritin-like ‘di-iron-carboxylate’ proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2011, 15, 291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Solomon EI; Brunold TC; Davis MI; Kemsley JN; Lee S-K; Lehnert N; Neese F; Skulan AJ; Yang Y-S; Zhou J Geometric and Electronic Structure/Function Correlations in Non-Heme Iron Enzymes. Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 235–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rokob TA; Chalupský J; Bím D; Andrikopoulos PC; Srnec M; Rulíšek L Mono- and binuclear non-heme iron chemistry from a theoretical perspective. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2016, 21, 619–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Friedle S; Reisner E; Lippard SJ Current challenges of modeling diironenzyme active sites for dioxygenactivation by biomimetic synthetic complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39, 2768–2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Harvey JN On the accuracy of density functional theory in transition metal chemistry. Annu. Rep. Prog. Chem., Sect. C: Phys. Chem 2006, 102, 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cramer CJ; Truhlar DG Density functional theory for transition metals and transition metal chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2009, 11, 10757–10816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ghosh A Just how good is DFT? J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2006, 11, 671–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Noodleman L; Lovell T; Han W-G; Li J; Himo F Quantum Chemical Studies of Intermediates and Reaction Pathways in Selected Enzymes and Catalytic Synthetic Systems. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 459–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ghosh A; Ab initio wavefunctions in bioinorganic chemistry: More than a succès d’estime? J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2011, 16, 819–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Blomberg MRA; Borowski T; Himo F; Liao RZ; Siegbahn PEM Quantum Chemical Studies of Mechanisms for Metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 3601–3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Nagai J; Bloch K Enzymatic desaturation of stearyl acyl carrier protein. J. Biol. Chem 1968, 243, 4626–4633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Morris LJ Mechanisms and stereochemistry in fatty acid metabolism. Biochem. J 1970, 118, 681–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Schmidt H; Heinz E Involvement of Ferredoxin in Desaturation of Lipid-Bound Oleate in Chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1990, 94, 214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wada H; Schmidt H; Heinz E; Murata N In vitro ferredoxin-dependent desaturation of fatty acids in cyanobacterial thylakoid membranes. J. Bacteriol 1993, 175, 544–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Fox BG; Lyle KS; Rogge CE Reactions of the diiron enzyme stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase. Acc. Chem. Res 2004, 37, 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Yang Y-S; Broadwater JA; Pulver SC; Fox BG; Solomon EI Circular Dichroism and Magnetic Circular Dichroism Studies of the Reduced Binuclear Non-Heme Iron Site of Stearoyl-ACP Δ9-Desaturase: Substrate Binding and Comparison to Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 2770–2783. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Broadwater JA; Achim C; Münck E; Fox BG Mössbauer studies of the formation and reactivity of a quasi-stable peroxo intermediate of stearoyl-acyl carrier protein Delta 9-desaturase. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 12197–12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Srnec M; Rokob TA; Schwartz JK; Kwak Y; Rulíšek L; Solomon EI Structural and spectroscopic properties of the peroxodiferric intermediate of Ricinus communis soluble Δ9 desaturase. Inorg. Chem 2012, 51, 2806–2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chalupský J; Rokob TA; Kurashige Y; Yanai T; Solomon EI; Rulíšek L; Srnec M Reactivity of the Binuclear Non-Heme Iron Active Site of Δ9 Desaturase Studied by Large-Scale Multireference Ab Initio Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 15977–15991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bochevarov AD; Li J; Song WJ; Friesner RA; Lippard SJ Insights into the Different Dioxygen Activation Pathways of Methane and Toluene Monooxygenase Hydroxylases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 7384–7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Jensen KP; Bell CB; Clay MD; Solomon EI Peroxo-Type Intermediates in Class I Ribonucleotide Reductase and Related Binuclear Non-Heme Iron Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 12155–12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Han W-G; Noodleman L Structural Model Studies for the Peroxo Intermediate P and the Reaction Pathway from P → Q of Methane Monooxygenase Using Broken-Symmetry Density Functional Calculations. Inorg. Chem 2008, 47, 2975–2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bochevarov AD; Friesner RA; Lippard SJ Prediction of 57Fe Mössbauer Parameters by Density Functional Theory: A Benchmark Study. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2010, 6, 3735–3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Siegbahn PEM Theoretical Model Studies of the Iron Dimer Complex of MMO and RNR. Inorg. Chem 1999, 38, 2880–2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Han W-G; Noodleman L DFT calculations for intermediate and active states of the diiron center with a tryptophan or tyrosine radical in Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. Inorg. Chem 2011, 50, 2302–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Han W-G; Noodleman L DFT calculations of comparative energetics and ENDOR/Mössbauer properties for two protonation states of the iron dimer cluster of ribonucleotide reductase intermediate X. Dalton Trans. 2009, 6045–6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rokob TA Pathways for Arene Oxidation in Non-Heme Diiron Enzymes: Lessons from Computational Studies on Benzoyl Coenzyme A Epoxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 14623–14638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Liu KE; Valentine AM; Wang D; Huynh BH; Edmondson DE; Salifoglou A; Lippard SJ Kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of intermediates and component interactions in reactions of methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 10174–10185. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lee SK; Fox BG; Froland WA; Lipscomb JD; Munck E A transient intermediate of the methane monooxygenase catalytic cycle containing an FeIVFeIV cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1993, 115, 6450–6451. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Shu L; Nesheim JC; Kauffmann K; Münck E; Lipscomb JD; Que L An Fe2IVO2 Diamond Core Structure for the Key Intermediate Q of Methane Monooxygenase. Science 1997, 275, 515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Brunold TC; Tamura N; Kitajima N; Moro-oka Y; Solomon EI Spectroscopic Study of [Fe2(O2)(OBz)2{HB(pź)3}2]: Nature of the μ−1,2 Peroxide–Fe(III) Bond and Its Possible Relevance to O2 Activation by Non-Heme Iron Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 5674–5690. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Skulan AJ; Brunold TC; Baldwin J; Saleh L; Bollinger JM Jr.; Solomon EI Nature of the Peroxo Intermediate of the W48F/D84E Ribonucleotide Reductase Variant: Implications for O2 Activation by Binuclear Non-Heme Iron Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 8842–8855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Saleh L; Krebs C; Ley BA; Naik S; Huynh BH; Bollinger JM Use of a Chemical Trigger for Electron Transfer to Characterize a Precursor to Cluster X in Assembly of the Iron-Radical Cofactor of Escherichia coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 5953–5964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bollinger JM; Tong WH; Ravi N; Huynh BH; Edmonson DE; Stubbe J Mechanism of Assembly of the Tyrosyl Radical-Diiron(III) Cofactor of E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. 2. Kinetics of The Excess Fe2+ Reaction by Optical, EPR, and Moessbauer Spectroscopies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 8015–8023. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bollinger JM; Stubbe J; Huynh BH; Edmondson DE Novel diferric radical intermediate responsible for tyrosyl radical formation in assembly of the cofactor of ribonucleotide reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 6289–6291. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Sturgeon BE; Burdi D; Chen S; Huynh B-H; Edmondson DE; Stubbe J; Hoffman BM Reconsideration of X, the Diiron Intermediate Formed during Cofactor Assembly in E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 7551–7557. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Siegbahn PEM; Svensson M On the internally contracted multireference CI method with full contraction. Int. J. Quantum Chem 1992, 41, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Werner H-J; Reinsch E-A The self-consistent electron pairs method for multiconfiguration reference state functions. J. Chem. Phys 1982, 76, 3144–3156. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Andersson K Different forms of the zeroth-order Hamiltonian in second-order perturbation theory with a complete active space self-consistent field reference function. Theor. Chim. Acta 1995, 91, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Andersson K; Malmqvist PA; Roos BO; Sadlej AJ; Wolinski K Second-order perturbation theory with a CASSCF reference function. J. Phys. Chem 1990, 94, 5483–5488. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Andersson K; Malmqvist PÅ; Roos BO Second- order perturbation theory with a complete active space self-consistent field reference function. J. Chem. Phys 1992, 96, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Li Manni G; Carlson RK; Luo S; Ma D; Olsen J; Truhlar DG; Gagliardi L Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2014, 10, 3669–3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Carlson RK; Li Manni G; Sonnenberger AL; Truhlar DG; Gagliardi L Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory: Barrier Heights and Main Group and Transition Metal Energetics. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2015, 11, 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lindqvist Y; Huang W; Schneider G; Shanklin J Crystal structure of delta9 stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase from castor seed and its relationship to other di-iron proteins. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 4081–4092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Guy JE; Whittle E; Moche M; Lengqvist J; Lindqvist Y; Shanklin, Remote control of regioselectivity in acyl-acyl carrier protein-desaturases. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2011, 108, 16594–16599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Ryde U The coordination of the catalytic zinc ion in alcohol dehydrogenase studied by combined quantum-chemical and molecular mechanics calculations. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des 1996, 10, 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Ryde U; Olsson MHM Structure, strain, and reorganization energy of blue copper models in the protein. Int. J. Quantum Chem 2001, 81, 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Reuter N; Dejaegere A; Maigret B; Karplus M Frontier Bonds in QM/MM Methods: A Comparison of Different Approaches. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 1720–1735. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Cao L; Ryde U On the Difference Between Additive and Subtractive QM/MM Calculations. Front. Chem 2018, 6, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Ahlrichs R; Bär M; Häser M; Horn H; Kölmel C Electronic structure calculations on workstation computers: The program system turbomole. Chem. Phys. Lett 1989, 162, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Tao J; Perdew JP; Staroverov VN; Scuseria GE Climbing the Density Functional Ladder: Nonempirical Meta–Generalized Gradient Approximation Designed for Molecules and Solids. Phys. Rev. Lett 2003, 91, 146401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Weigend F; Ahlrichs R Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Grimme S; Antony J; Ehrlich S; Krieg H A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Eichkorn K; Treutler O; Öhm H; Häser M; Ahlrichs R Auxiliary basis sets to approximate Coulomb potentials. Chem. Phys. Lett 1995, 240, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Maier JA; Martinez C; Kasavajhala K; Wickstrom L; Hauser KE; Simmerling C ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Reiher M; Salomon O; Hess BA Reparameterization of hybrid functionals based on energy differences of states of different multiplicity. Theor. Chem. Acc 2001, 107, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Aquilante F; De Vico L; Ferré N; Ghigo G; Malmqvist P.-å.; Neogrády P; Pedersen TB; Pitoňák M; Reiher M; Roos BO; Serrano-Andrés L; Urban M; Veryazov V; Lindh R MOLCAS 7: the next generation. J. Comput. Chem 2010, 31, 224–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Aquilante F; Autschbach J; Carlson RK; Chibotaru LF; Delcey MG; De Vico L; Fdez. Galván I; Ferré N; Frutos LM; Gagliardi L; Garavelli M; Giussani A; Hoyer CE; Li Manni G; Lischka H; Ma D; Malmqvist PÅ; Müller T; Nenov A; Olivucci M; Pedersen TB; Peng D; Plasser F; Pritchard B; Reiher M; Rivalta I; Schapiro I; Segarra-Martí J; Stenrup M; Truhlar DG; Ungur L; Valentini A; Vancoillie S; Veryazov V; Vysotskiy VP; Weingart O; Zapata F; Lindh R Molcas 8: New capabilities for multiconfigurational quantum chemical calculations across the periodic table. J. Comput. Chem 2016, 37, 506–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Veryazov V; Widmark P-O; Serrano-Andrés L; Lindh R; Roos BO 2MOLCAS as a development platform for quantum chemistry software. Int. J. Quantum Chem 2004, 100, 626–635. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Karlström G; Lindh R; Malmqvist P-Å; Roos BO; Ryde U; Veryazov V; Widmark P-O; Cossi M; Schimmelpfennig B; Neogrady P; Seijo L MOLCAS: a program package for computational chemistry. Comput. Mater. Sci 2003, 28, 222–239. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Siegbahn PEM; Almlöf J; Heiberg A; Roos BO The complete active space SCF (CASSCF) method in a Newton–Raphson formulation with application to the HNO molecule. J. Chem. Phys 1981, 74, 2384–2396. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Roos BO; Taylor PR; Siegbahn PEM A complete active space SCF method (CASSCF) using a density matrix formulated super-CI approach. Chem. Phys 1980, 48, 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Widmark P-O; Malmqvist P-Å; Roos BO Density matrix averaged atomic natural orbital (ANO) basis sets for correlated molecular wave functions. Theor. Chim. Acta 1990, 77, 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Roos BO; Lindh R; Malmqvist P-Å; Veryazov V; Widmark P-O New Relativistic ANO Basis Sets for Transition Metal Atoms. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 6575–6579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Douglas M; Kroll NM Quantum electrodynamical corrections to the fine structure of helium. Ann. Phys 1974, 82, 89–155. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Hess BA Relativistic electronic-structure calculations employing a two-component no-pair formalism with external-field projection operators. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 33, 3742–3748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Jansen G; Hess BA Revision of the Douglas-Kroll transformation. Phys. Rev. A 1989, 39, 6016–6017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Aquilante F; Malmqvist P-Å; Pedersen TB; Ghosh A; Roos BO Cholesky Decomposition-Based Multiconfiguration Second-Order Perturbation Theory (CD-CASPT2): Application to the Spin-State Energetics of Co(III)(diiminato)(NPh). J. Chem. Theory Comput 2008, 4, 694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Carlson RK; Truhlar DG; Gagliardi L Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory: A Fully Translated Gradient Approximation and Its Performance for Transition Metal Dimers and the Spectroscopy of Re2Cl82–. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2015, 11, 4077–4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Kelly CP; Cramer CJ; Truhlar DG Aqueous solvation free energies of ions and ion-water clusters based on an accurate value for the absolute aqueous solvation free energy of the proton. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 16066–16081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Namazian M; Lin CY; Coote ML Benchmark Calculations of Absolute Reduction Potential of Ferricinium/Ferrocene Couple in Nonaqueous Solutions. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2010, 6, 2721–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Noodleman L; Du W-GH; Fee JA; Götz AW; Walker RC Linking Chemical Electron–Proton Transfer to Proton Pumping in Cytochrome c Oxidase: Broken-Symmetry DFT Exploration of Intermediates along the Catalytic Reaction Pathway of the Iron–Copper Dinuclear Complex. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 6458–6472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Klamt A; Schuurmann G COSMO: a new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc.-Perkin Trans 2 1993, 799–805. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Klamt A Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents: A New Approach to the Quantitative Calculation of Solvation Phenomena. J. Phys. Chem 1995, 99, 2224–2235. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Klamt A; Jonas V; Bürger T; Lohrenz JC Refinement and Parametrization of COSMO-RS. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 5074–5085. [Google Scholar]

- (76).NCBI Resource Coordinators, Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 46, Issue D1, 4 January 2018, Pages D8–D13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Sievers F; Wilm A; Dineen D; Gibson TJ; Karplus K; Li W; Lopez R; McWilliam H; Remmert M; Söding J; Thompson JD; Higgins DG Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol 2011, 7, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Sievers F; Higgins DG Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Elango NA; Radhakrishnan R; Froland WA; Wallar BJ; Earhart CA; Lipscomb JD; Ohlendorf DH Crystal structure of the hydroxylase component of methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Protein Sci. 1997, 6, 556–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Rather LJ; Weinert T; Demmer U; Bill E; Ismail W; Fuchs G; Ermler U Structure and Mechanism of the Diiron Benzoyl-Coenzyme A Epoxidase BoxB. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 29241–29248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Choi YS; Zhang H; Brunzelle JS; Nair SK; Zhao H In vitro reconstitution and crystal structure of p-aminobenzoate N-oxygenase (AurF) involved in aureothin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 6858–6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Bailey LJ; McCoy JG; Phillips GN; Fox BG Structural consequences of effector protein complex formation in a diiron hydroxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 19194–19198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Archer M; Carvalho AL; Teixeira S; Moura I; Moura JJG; Rusnak F; Romão MJ Structural studies by X-ray diffraction on metal substituted desulforedoxin, a rubredoxin-type protein. Protein Sci. 1999, 8, 1536–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Högbom M; Galander M; Andersson M; Kolberg M; Hofbauer W; Lassmann G; Nordlund P; Lendzian F Displacement of the tyrosyl radical cofactor in ribonucleotide reductase obtained by single-crystal high-field EPR and 1.4-Å x-ray data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2003, 100, 3209–3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Pei J; Kim B-H; Grishin NV PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2295–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Lyle KS; Haas JA; Fox BG Rapid-Mix and Chemical Quench Studies of Ferredoxin-Reduced Stearoyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Desaturase. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 5857–5866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Saitow M; Kurashige Y; Yanai T Multireference configuration interaction theory using cumulant reconstruction with internal contraction of density matrix renormalization group wave function. J. Chem. Phys 2013, 139, 044118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Tinberg CE; Lippard SJ Dioxygen Activation in Soluble Methane Monooxygenase. Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Cutsail GE; Banerjee R; Zhou A; Que L; Lipscomb JD; DeBeer S High-Resolution Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure Analysis Provides Evidence for a Longer Fe···Fe Distance in the Q Intermediate of Methane Monooxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 16807–16820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Rinaldo D; Philipp DM; Lippard SJ; Friesner RA Intermediates in Dioxygen Activation by Methane Monooxygenase: A QM/MM Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 3135–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Reece SY; Nocera DG Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Biology: Results from Synergistic Studies in Natural and Model Systems. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2009, 78, 673–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Gagliardi CJ; Vannucci AK; Concepcion JJ; Chen Z; Meyer TJ The role of proton coupled electron transfer in water oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci 2012, 5, 7704–7717. [Google Scholar]

- (93).Hammes-Schiffer S; Soudackov AV Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Solution, Proteins, and Electrochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 14108–14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Chang CJ; Chang MCY; Damrauer NH; Nocera DG Proton-coupled electron transfer: a unifying mechanism for biological charge transport, amino acid radical initiation and propagation, and bond making/breaking reactions of water and oxygen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1655, 13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Cammack R; Rao KK; Bargeron CP; Hutson KG; Andrew PW; Rogers LJ Midpoint redox potentials of plant and algal ferredoxins. Biochem. J 1977, 168, 205–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Wang D; Farquhar ER; Stubna A; Münck E; Que L Jr A diiron(IV) complex that cleaves strong C-H and O-H bonds. Nat. Chem 2009, 1, 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Xue G; Wang D; De Hont R; Fiedler AT; Shan X; Münck E; Que L A synthetic precedent for the [FeIV2(μ-O)2] diamond core proposed for methane monooxygenase intermediate Q. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2007, 104, 20713–20718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Cho K-B; Hirao H; Shaik S; Nam W To rebound or dissociate? This is the mechanistic question in C–H hydroxylation by heme and nonheme metal–oxo complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45, 1197–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Huang X; Groves JT Beyond ferryl-mediated hydroxylation: 40 years of the rebound mechanism and C-H activation. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2017, 22, 185–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Pangia TM; Yadav V; Gérard EF; Lin Y-T; de Visser SP; Jameson GNL; Goldberg DP Mechanistic Investigation of Oxygen Rebound in a Mononuclear Nonheme Iron Complex. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 9557–9561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Srnec M; Solomon EI Frontier Molecular Orbital Contributions to Chlorination versus Hydroxylation Selectivity in the Non-Heme Iron Halogenase SyrB2. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2396–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Whittle EJ; Tremblay AE; Buist PH; Shanklin J Revealing the catalytic potential of an acyl-ACP desaturase: Tandem selective oxidation of saturated fatty acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 14738–14743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Behrouzian B; Buist PH Bioorganic chemistry of plant lipid desaturation. Phytochem. Rev 2003, 2, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- (104).Park K; Li N; Kwak Y; Srnec M; Bell CB; Liu LV; Wong SD; Yoda Y; Kitao S; Seto M; Hu M; Zhao J; Krebs C; Bollinger JM; Solomon EI Peroxide Activation for Electrophilic Reactivity by the Binuclear Non-heme Iron Enzyme AurF. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7062–7070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Acheson JF; Bailey LJ; Brunold TC; Fox BG In-crystal reaction cycle of a toluene-bound diiron hydroxylase. Nature 2017, 544, 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Makris TM; Vu VV; Meier KK; Komor AJ; Rivard BS; Münck E; Que L; Lipscomb JD An Unusual Peroxo Intermediate of the Arylamine Oxygenase of the Chloramphenicol Biosynthetic Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1608–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Jasniewski AJ; Komor AJ; Lipscomb JD; Que L Unprecedented (μ−1,1-Peroxo)diferric Structure for the Ambiphilic Orange Peroxo Intermediate of the Nonheme N-Oxygenase CmlI. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 10472–10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).Song WJ; McCormick MS; Behan RK; Sazinsky MH; Jiang W; Lin J; Krebs C; Lippard SJ Active site threonine facilitates proton transfer during dioxygen activation at the diiron center of toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase hydroxylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 13582–13585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Guy JE; Abreu IA; Moche M; Lindqvist Y; Whittle E; Shanklin J A single mutation in the castor Δ9–18:0-desaturase changes reaction partitioning from desaturation to oxidase chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 17220–17224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Sobrado P; Lyle KS; Kaul SP; Turco MM; Arabshahi I; Marwah A; Fox BG Identification of the Binding Region of the [2Fe-2S] Ferredoxin in Stearoyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Desaturase: Insight into the Catalytic Complex and Mechanism of Action. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 4848–4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (111).Lendzian F; Sahlin M; MacMillan F; Bittl R; Fiege R; Pötsch S; Sjöberg B-M; Gräslund A; Lubitz W; Lassmann G Electronic Structure of Neutral Tryptophan Radicals in Ribonucleotide Reductase Studied by EPR and ENDOR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 8111–8120. [Google Scholar]

- (112).Mitić N; Clay MD; Saleh L; Bollinger JM; Solomon EI Spectroscopic and Electronic Structure Studies of Intermediate X in Ribonucleotide Reductase R2 and Two Variants: A Description of the FeIV-Oxo Bond in the FeIII–O–FeIV Dimer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 9049–9065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.