Abstract

For type 1 diabetics, islet transplantation can induce beneficial outcomes, including insulin independence and improved glycemic control. The long-term function of the grafted tissue, however, is challenged by host inflammatory and immune responses. Cell encapsulation can decrease detrimental host responses to the foreign implant, but standard microencapsulation imparts large transplant volumes and impaired metabolite and nutrient diffusion. To mitigate these effects, we developed an efficient covalent Layer-by-Layer (cLbL) approach for live-cell nanoencapsulation, based on oppositely charged hyperbranched polymers functionalized with complementary Staudinger ligation groups. Reliance on cationic polymers for cLbL, however, is problematic due to their poor biocompatibility. Herein, we incorporated the additional feature of supramolecular self-assembly of the dendritic polymers to enhance layer uniformity and decrease net polymer charge. Functionalization of poly (amino amide) (PAMAM) with triethoxysilane decreased polymer charge without compromising the uniformity and stability of resulting nanoscale islet coatings. Encapsulated pancreatic rat islets were viable and functional. The implantation of cLbL islets into diabetic mice resulted in stable normoglycemia, at equivalent dosage and efficiency as uncoated islets, with no observable alterations in cellular engraftment or foreign body responses. By balancing multi-functionality and self-assembly, nano-scale and stable covalent layer-by-layer polymeric coatings could be efficiently generated onto cellular organoids, presenting a highly adaptable platform for broad use in cellular transplantation.

Keywords: diabetes, dendritic polymer, alginate, layer-by-layer, conformal coating

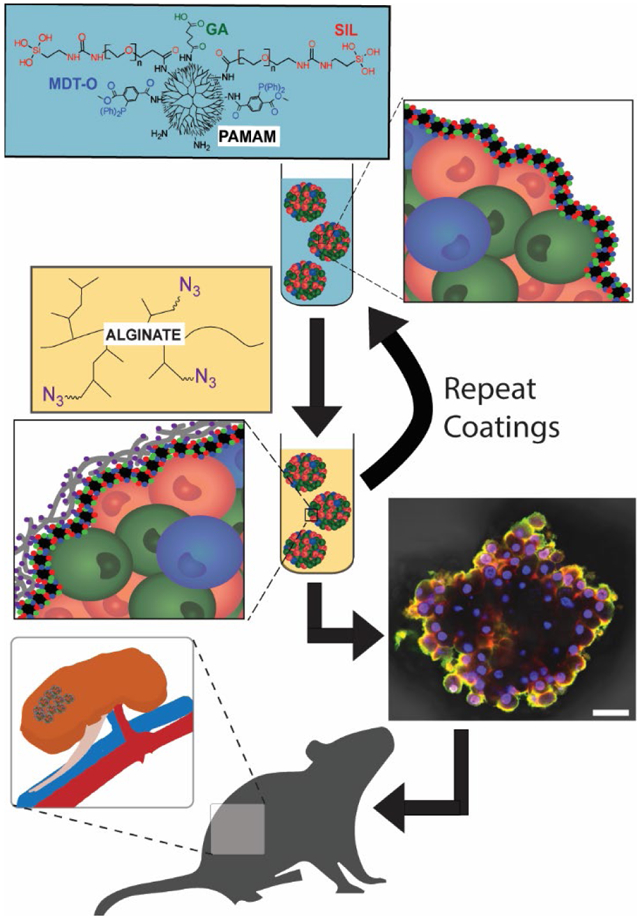

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease that selectively destroys the insulin-producing β-cells within the pancreatic islet, resulting in reliance on exogenous insulin for maintenance of glycemic control. While insulin injections prevent the lethality of this disease, non-physiological glucose levels elevate the risk of cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, nephropathy, and other complications.(1) Cell therapy, particularly clinical islet transplantation (CIT), has the potential to provide an effective cure for T1D. The current CIT protocol involves the isolation of islets from cadaveric donors followed by their intrahepatic implantation via the portal vein.(2) Although this approach has shown the potential to treat even the most glycemic liable patients,(3) rejection of islet transplants and loss in functional β-cell mass is inevitable, despite the use of a rigorous immunosuppressive regimen.(4)

Following allogeneic islet transplantation, adaptive immune responses in the T1D recipient are potently activated by both allogeneic and autogenic signals.(5) Immune cells recognize these instigative antigens, either via direct or indirect recognition pathways, and trigger adaptive immune responses that result in the efficient destruction of the foreign implant. While immunosuppressive drugs for CIT recipients focus on the depletion and/or inactivation of host T cells, these anti-rejection drugs are administered systemically, which elevates the risk for opportunistic infections, imparts toxicity to the islets, and generates other unpredictable and undesirable side effects.(6)

To avoid these detrimental effects, methods to block immune activation in CIT without the use of systemic immunosuppressants are actively being explored. Among these methods, polymeric islet encapsulation is a promising approach.(7) Islet encapsulation offers a perm-selective barrier that allows the effective efflux and influx of nutrients (e.g. oxygen and glucose) and insulin, while blocking immune cells, antibodies, and complement system proteins.(8) While numerous groups have demonstrated the capacity of macro- and micro-encapsulation to prevent immune recognition and rejection of islets, the clinical translation of these approaches is challenging. Specifically, standard encapsulation approaches impart micro- to macro-scale barriers that substantially delay the exchange of insulin and nutrients, resulting in poor glycemic control and hypoxia-induced necrosis of the encapsulated cells. Furthermore, the size of these capsules restricts the implant site to unfavorable locations (e.g. intraperitoneal, subcutaneous) that further exacerbate nutritional deficiencies.(9-11)

An alternative to micro encapsulation is the use of ultrathin conformal coatings. This approach includes PEGylation (grafting polyethylene glycol to the cell surface), layer-by-layer (LbL) self-assembled films, and two-phase fluidic systems.(12) LbL approaches for coating cell clusters commonly utilize electrostatic interactions, due to the ease in efficiently building multiple layers.(13-16) While highly promising, reliance on electrostatic interactions to generate coatings onto viable and dynamic cell clusters inherently leads to poor long-term stability and biocompatibility.(17-19) In our laboratory, we have focused on engineering covalently-stabilized layer-by-layer (cLbL) coatings, which can provide both stability and control over coating conformity and thickness.(20) Dendrimers, highly branched macromolecules, are ideal platforms for cLbL, due to their spherical structure and ease of functionalization.(21) Our recent efforts using polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer polymers have resulted in cLbL coatings on pancreatic islets, stabilized via Staudinger ligation and electrostatic cross-links.(20) While promising, highly cationic PAMAM-based coatings exhibited significant cytotoxicity, while net neutral dendrimers were unable to form stable layers. Herein, we sought to improve on this platform by promoting dendrimer interactions and self-assembly during the coating process. As surface R-Si(-OH)3 functionalization has been shown to promote polymer self-assembly via hydrogen bonding and condensation,(22) we postulated that the incorporation of silanetriols onto the PAMAM dendrimer would enhance coating uniformity when the net charge of the PAMAM was decreased. Herein, we examined the capacity of this approach to generate uniform and stable coatings onto pancreatic islets, as well as the impact of the coatings on islet viability and transplant efficacy in a murine diabetic model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Triethoxysilane-PEG-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (SIL-NHS, MW 2000 kDa) was purchased from Nanocs (New York, NY). 5(6)-Carboxy-X-rhodamine NHS ester (Rox-NHS) was from Adipogen Corp. (San Diego, CA). Alginate (PRONOVA UP VLVG) was from NovaMatrix (Sandvika, Norway). Ultrapure water was obtained from a Millipore Synergy® Water Purification System. All other reagents or materials were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific, respectively.

Polymer characterization

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta (ζ) potential measurements were collected from polymer solutions (1 mg/ml; buffer 10 mM 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid and 10 mM KNO3 with pH 7.4) utilizing a Particle Sizing Systems Nicomp ZLS Z3000 instrument at room temperature. DLS results were the average of 10 runs of 30 s each. Zeta potential results were the average of 3 runs of 3 cycles each using an E-field of 4.5 V. The PerkinElmer Frontier spectrometer was utilized to obtain the attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectra. The spectrometer was equipped with desiccated Ge-coated KBr optics, a temperature-stabilized deuterated triglycine sulfate detector, and 1 reflection diamond/ZnSe universal ATR sampling accessory.

Synthesis of functionalized PAMAM

The synthetic reaction conditions were optimized, whereby 92% of the added reactive reagents conjugated to the primary amines on the surface of the PAMAM dendrimer, as previously reported.(20) A solution of 9.5 mg 2-(diphenylphosphino)terephthalic acid 1-methyl 4-pentafluorophenyl diester (MDT), 9.2 mg SIL-NHS, 0.87 mg Rox-NHS (for fluorescent imaging only), and 0.5 ml dichloromethane (DCM) was drop-wise injected to 1 ml polyamidoamine (PAMAM, generation 5, ethylenediamine core, 5 wt. % in methanol) under stirring and Ar atmosphere. After 30 min, a solution of 4.8 mg glutaric anhydride (GA), 4.8 mg NHS, 0.5 ml DCM (dried over molecular sieves), and 6 μl triethylamine (TEA) was injected (drop-wise) under continuous agitation and incubated for an additional 30 min. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in 5 ml of 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (10 mM MOPS, 125 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, pH 7.4), pH adjusted to 7.4 with HCl, and purified utilizing one Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (30 kDa MWCO, 5 x 5 ml MOPS buffer) and centrifugation (10 min, 4000 x g). The final PAMAM solution was then filtered through a cotton wool plug inside a glass Pasteur pipette and suspended in 1.8 ml of MOPS buffer. A sample of 0.4 ml was desalted and freeze-dried to calculate yield. The PAMAM solution was then stored under Ar at −20 °C. Yield = 41 ± 5 mg. ATR-FTIR selected characteristic bands: 3261, 3068, 2937, 2870 (PEG C-H symmetric stretch), 2834, 1720 (MDT), 1632, 1539 (Amide II), 746 (MDT), and 697 (MDT) cm−1. When stored at −20 °C, thawed PAMAM solutions showed no signs of flocculation for at least 3 months, but aged samples (> 1 month) exhibited decreased coating capacity. Hence, PAMAM solutions were used only within 1 week of fabrication.

Synthesis of functionalized hyperbranched alginate

Hyperbranched alginate was fabricated using methods previously described with some modifications.(20) Specifically, 5 mg NHS, 25 mg of 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), and 80 mg of N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N’-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) was added to a stirring solution of 50 mg alginate in 2 ml water. Separately, 15 mg of 3,5-dicarboxyphenyl glycineamide and H2N-PEG-COOH (MW 700 kDa) were dissolved in 130 μL of 1 M NaOH or 0.20 ml water, respectively. Both solutions were mixed, filtered, and added to the alginate solution at 50 μl/min. After 20 min, added 200 μl of 0.5 M NaOH at 5 μl/min. After 20 min, the product was purified with an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (MWCO 30k, 3 x 3 ml MOPS buffer then 2 x 3 ml; water), filter-sterilized (0.2 μm), and freeze-dried. Yield 49 mg of a white, foamy solid film. Kaiser test: Negative. Next, to 25 mg of the obtained product, 25 mg H2N-PEG-N3 (MW 350.41), 1 mg 4-(aminomethyl)fluorescein HCl (only for fluorescent labeling), 25 mg of N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide sodium salt, 25 mg MES, and 55 mg EDC was added to a solution of 25 mg product from step 1 in 1 ml water. After 20 min, added 800 μl of 0.25 M NaOH at 50 μl/min. After 20 min, the product was purified with Amicon ultra-15 centrifugal filter (MWCO 10k, 5 x 3 ml MOPS, 2 x 3 ml water), filter-sterilized, and freeze-dried. Yield 29 mg of a white (or orange if fluorescently labeled) foamy solid film. Kaiser test negative. ATR-FTIR selected characteristic bands: 3310 (O-H stretch), 2912, 2873 (PEG C-H symmetric stretch), 2108 (N3 asymmetric stretch), 1650 (amide C=O stretch), 1607 (alginate CO2− asymmetric stretch), 1545 (amide II), 1090, and 1029 cm−1. To generate a working solution of Alg-HyPEG-N3, it was fully dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH at 30 mg/ml. After being diluted to 10 mg/ml with MOPS buffer, its pH was adjusted to 7.4 with 0.1 M HCl. From the resulting 7.5 mg/ml solution, the working solution of 3 mg/ml in MOPS+Glu was prepared.

Layer-by-layer (LbL) Film Deposition onto Idealized Planar Surface

A silicon wafer (~11x13 mm) was treated with 0.1 M NaOH for 1 min at 80 °C and washed three times with water. The resulting Si wafer was coated with alternating layers of PAMAM and hyperbranched alginate, with or without a fluorescein label. After each layer, excess polymer was removed via three washes with MOPS buffer, water, and ethanol, and dried via argon. Surface film thickness was measured via J. A. Woollam Co. alpha-SE spectroscopic ellipsometer, at a 70° angle and standard mode settings, using the transparent film data model. Three readings were collected for each data point.

Coating of pancreatic islets

Lewis rat islets were isolated as previously described and cultured for 48 h in standard islet culture media (CMRL 1066 media supplemented with 8.7 % (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 330 mg/l of L-glutamine, 96 U/ml of penicillin, 96 mg/l of streptomycin, and 22 ml/l of 1 M HEPES buffer) prior to coating.(20, 23) For coating, islets were transferred to a centrifuge tube and media was removed when islets pelleted by gravity. The islet pellet was rinsed twice with MOPS buffer supplemented with 0.5 mg glucose/ml (MOPS+Glu) and suspended in the polymer solution (3 mg/ml in MOPS+Glu) at 10k IEQ/ml, placed inside a cell culture incubator for 10 min at 37 °C with a mixing at 5 min, and rinsed 3 times with MOPS buffer. For multiple layers, this procedure was repeated (pelleting, resuspension in 3 mg/ml polymer for 10 mins, and rinsing with MOPS). Following the coating procedure, islets were cultured in standard islet culture media under standard incubator conditions prior to assessments.

Islet assessment

Islet assessments were performed at day 1 and 5 post-coating. Coating features, uniformity, stability were assessed via confocal imaging. For confocal microscopy images of the coating, fluorescently labeled PAMAM (red) and Alg-HyPEG-N3 (green) were utilized. For stability characterization, samples of coated islets were cultured and coatings imaged as designed time points. Coating uniformity was characterized using ImageJ with quantification of defects via % islet area exhibiting non-fluorescence. Mean intensity of coatings was measured by quantification of the green channel (corresponding to fluorescein-labeled hyperbranched alginate) over 20 line profiles from 3D projections of 3-5 islets at 40x using the LAS X quantify tool. For immunohistochemical analysis, islets were fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h prior to co-staining for insulin (Rabbit anti-insulin monoclonal primary antibody, 1:400, 3 h, 4 °C; goat anti-rabbit AF488 IgG, 1:200, 2 h, 4 °C), F-actin (Phalloidin AF680), and DAPI (cell nuclei). A Leica SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope (scan format 1024 x 1024, 3D projections: 20-40 slides at 1.5 μm thickness) was utilized for confocal images. For live/dead assessment, calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1 were utilized to fluorescently label viable (green) and dead (red) cells and images were collected using confocal microscopy. Cell metabolic activity was assessed with the MTT assay in triplicates of 150 IEQ each. MTT results were graphed relative to the uncoated control islets. To account for any variance in IEQ counts, absorbance was normalized to islet surface area, as imaged following MTT incubation and measured using Image J on binary images. Static glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) was performed as previously reported, (24) where islets were incubated 1 h consecutively in low (3 mM), high (11 mM), and low glucose concentration in Krebs buffer (115 mM NaCl2, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 0.2% w/v BSA, and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) followed by insulin sample collection. For dynamic glucose stimulated insulin release, 50 islets (handpicked) were loaded into our islet-chip platform and connected to a PERI-4.2 perifusion system (Biorep Technologies, Miami Lakes, FL) and perifused at 30 μL/min, as previously published.(25) Islets were first pre-incubated for 60 mins under low glucose (3 mM). For stimulation, islets were exposed for 10 mins to low glucose (3 mM), followed by 20 mins high glucose (11 mM) and 20 mins low glucose (3 mM). Analytes were collected at every 2 min from the outflow tubing and stored at −80°C. Insulin concentrations from both assays were quantified using a Mercodia rat ELISA kit and a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 microplate reader. Insulin concentrations were normalized with respect to the total DNA content of samples utilizing the Molecular Probes Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit. Dynamic assays were converted to pg/min using the constant flow rate as listed above and normalized to islet number (IN).

Islet transplantation

All animal procedures were conducted under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols at the University of Florida. Non-obese diabetic, immunodeficient (NOD-SCID) mice (7-9 weeks) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were induced with diabetes with five daily intraperitoneal (IP) injections of 40 mg/ml of Streptozotocin (STZ) (Sigma-Aldrich). Mice were classified as diabetic after three consecutive BG readings above 350 mg/dl. Diabetic mice received a full mass Lewis rat islet transplant (750 IEQ) into the kidney capsule. Diabetic mice were transplanted with either coated or non-coated islets. For coatings, islets were coated two days after isolation and both groups were transplanted one day after coating. For the kidney capsule transplant, diabetic mice were prepared for surgery, and anesthetized via isoflurane. The kidney was mobilized, a small incision and pocket was made in the subcapsular space, rat islets were infused into the subcapsular space via Hamilton syringe, and the incision was cauterized. The surgical wound was sutured using a 5.0 polydioxanone suture (Ethicon). All mice were monitored for blood glucose and weight, with euglycemia defined as 2 consecutive readings of blood glucose < 200 mg/dl. Successful grafts underwent survival surgeries with nephrectomy at days 30, 70, or 90, with subsequent monitoring of restoration to diabetic state after islet graft removal. Explants were fixed in 10 % formalin buffer, followed by paraffin embedding and sectioning (5-10 μm). Slides were then de-paraffinized and stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and then imaged with a light microscope 10X and 20X magnifications (Zeiss Axio Observer). For immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, the de-paraffinized tissues were first permeabilized with 0.3 % TritonX100 in PBS for 1 h and blocked with 10 % goat serum (BioGenex HK112-9k) for 1 h. Then, a mix of guinea pig polyclonal anti-insulin (Dako A0564, 1:800) and rabbit polyclonal anti α-smooth muscle actin (ab5694, 1:200) primary antibodies in diluent (BioGenex HK156-5k) was added to the above-treated tissues. Following overnight exposure to the antibodies at 4 °C, tissues were rinsed with diluent (four times for 10 min) and treated with a mix of 4,6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Thermo Scientific Pierce DAPI 62248, 1:1000), ActinGreen (Invitrogen R37110, 2 drops/ml), goat anti-rabbit IgG AF 568 (Invitrogen A11036, 1:200), and goat anti-guinea pig AF 647 (Life Technology A21450, 1:200) for 1 h. Finally, the tissues were rinsed as above, added Prolong Gold Antifade with DAPI (Invitrogen P36931), covered with a coverslip, edges sealed with Cytoseal, and air-dried. Fluorescent images were taken utilizing a confocal laser scanning fluorescent microscope (Leica TCS SP8).

Statistical analysis and software

For all results, a minimum of 3 biological replicates were collected. For islet studies, a minimum of 2 independent isolations were assessed (n ≥ 3 biological replicates for each assessment within each isolation) to validate observed trends. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). One-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparison tests were utilized to compare more than two means. For only two means, an F test was first done to evaluate variances prior to a two-tail T-test. Significance was achieved when P < 0.05. For analysis of diabetes reversal, a Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed. To compare BG stability in xenograft transplants, a two-way repeated-measure ANOVA was performed with Greenhouse-Geisserpost hoc analysis to compare within-subject effects. All statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (v 8.0). ACD/ChemSketch (freeware version 12.01) was utilized to draw chemical structures.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Polymer functionalization and characterization

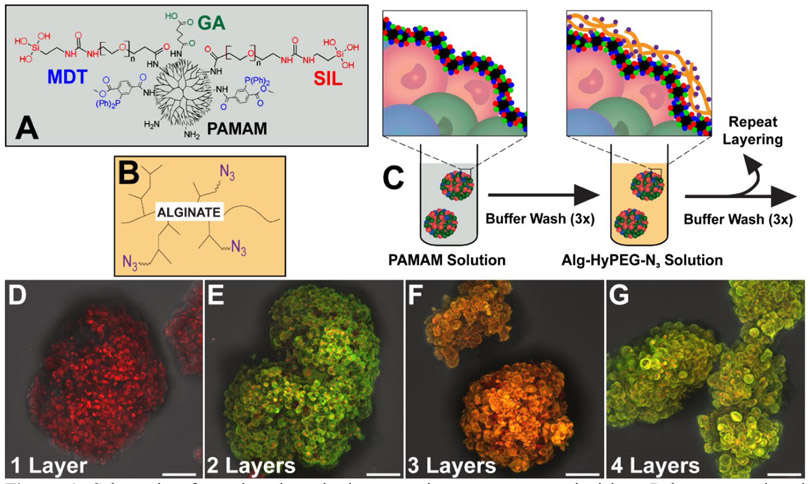

As shown in Figure 1A, up to three distinct functional groups were conjugated to the PAMAM terminal amines: 2-(diphenylphosphino)terephthalic acid 1-methyl 4-pentafluorophenyl diester (MDT); glutaric anhydride (GA); and triethoxysilane-PEG (SIL). The MDT served to provide a stable phosphine group to undergo chemoselective Staudinger ligation with a complementary N3 group. Linking N3 to hyperbranched alginate (azido-functionalized hyperbranched alginate (Alg-HyPEG-N3); Figure 1B) permitted the spontaneous formation of covalent bonds between these polymers during covalent layer-by-layer (cLbL) formation. The GA group was utilized to modulate the net charge of the PAMAM, whereby increased GA functionalization reduced the cationic properties of the PAMAM, as previously described. (20) The SIL group was used to facilitate self-assembly of the PAMAM during layer formation. It was hypothesized that the silanization of the PAMAM spheroidal dendrimers during coating would improve the uniformity of deposition, thereby permitting decreased dependency on positive charge for efficient polymer layer formation onto the pancreatic islet.

Figure 1.

Schematic of covalent layer-by-layer coatings onto pancreatic islets. Polymers employed included A) PAMAM, functionalized with up to 3 distinct groups, MDT, SIL, and GA (see Table 1 for summary); and B) hyperbranched alginate, functionalized with N3. C) Islets were coated in a layer-by-layer manner, with 10 min incubation and washes between coatings. D-G) Z-stack projection confocal images of layer formation on pancreatic islets, building from one (D), two (E), three (F), and four (G) alternating layers of PAMAM-MDT/SIL and Alg-HyPEG-N3. Scale bar = 50 μm.

To delineate the contributions of charge and silanization on coating properties, four distinct functionalized PAMAM dendrimers were generated: PAMAM-MDT, which was only functionalized with MDT; PAMAM-MDT/GA, which was functionalized with MDT and GA; PAMAM-MDT/SIL, which was functionalized with MDT and SIL; and PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL, which was functionalized with MDT, GA, and SIL. Table 1 summarizes the composition and characterization of the modified dendrimers employed in this study. GA or SIL functionalization decreased the zeta-potential of the products by 27 or 20%, respectively, when compared to PAMAM-MDT. Functionalization of PAMAM with MDT, GA, and SIL further decreased the polymer’s overall zeta potential by almost 60% when compared to PAMAM-MDT. The decreased net positive charge for GA and SIL functionalized PAMAM dendrimers could elevate their aggregation potential, which may explain their measured multi-modal DLS distributions (Table 1). ATR-FTIR was used to confirm the functionalization of PAMAM and Alg-HyPEG-N3 (Figure S1). As summarized in Figure S1A, characteristic IR bond vibrations of PAMAM, MDT, GA, and PEG were measured for PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL. For the functionalized hyper-branched alginate (Alg-HyPEG-N3), azido, alginate, PEG, and amide bond vibrations were detected (Figure S1B). Of note, the protocol for generating Alg-HyPEG-N3 was modified enhance solubility by decreasing the degree of hyperbranching when compared to our previously published work.(20)

Table 1.

Composition and characterization of functionalized PAMAMs.

| ID | PAMAM functionalization |

ζ-Potential | Diameter, nm (% intensity) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDT | GA | PEG-SIL | |||

| PAMAM-MDT | 13 | 0 | 0 | 41.74 ± 1.15 | 10 (100%) |

| PAMAM-MDT/GA | 13 | 30 | 0 | 30.66 ± 0.56 | 10 (6%); 169 (47%); 1000 (47%) |

| PAMAM-MDT/SIL | 13 | 0 | 3 | 33.45 ± 0.28 | 10 (2%); 35 (1%); 285 (97%) |

| PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL | 13 | 30 | 3 | 17.14 ± 0.81 | 10 (3%); 208 (57%); 811 (40%) |

Coating of pancreatic islets

To evaluate the impact of PAMAM functionalization on coating uniformity and stability, pancreatic rat islets were isolated and coated with alternating layers of PAMAM and Alg-HyPEG-N3. For the efficient generation of layers, incubation times of 10 mins per coating were used. To visualize coatings, PAMAM was labeled with Rox and Alg-HyPEG-N3 was labeled with fluorescein. Note the presence of these labels did not alter layer formation, as validated in Figure S2. As shown in Figure 1C-G, confocal imaging tracked the building of discreet layer-by-layer coatings onto the islet surface with each alternating incubation in either PAMAM (red) or Alg-HyPEG-N3 (green) polymers. After only 4 total polymeric layers (or 2 bi-layers of alternating polymers), coatings on the irregular pancreatic islet spheroid were robust.

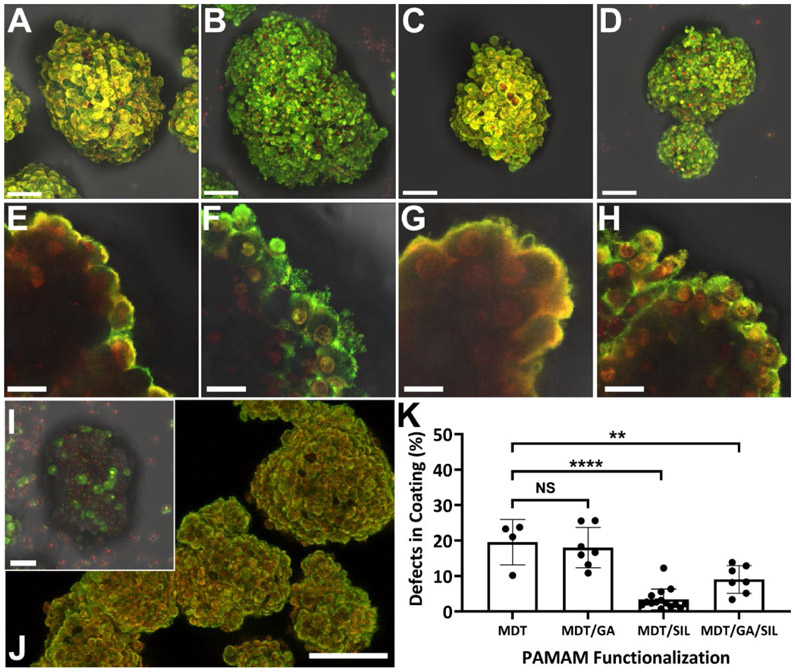

A comparison of the impact of PAMAM functionalization on the features of the 4-layer coating is summarized in Figure 2. Layers formed using PAMAM-MDT, a polycationic PAMAM functionalized with only MDT, were conformal, ultrathin, and generally uniform (Figure 2A&E) with moderate defects (19.59 ± 6.4%, Figure 2K); however, our previous studies have shown that the net positive charge of this PAMAM polymer results in cytotoxicity.(20) Decreasing the PAMAM net charge via GA functionalization (PAMAM-MDT/GA; Figure 2B&F) did not substantially alter coating coverage (p = 0.94; Figure 2K). Functionalizing PAMAM with SIL (PAMAM-MDT/SIL; Figure 2C&G), however, resulted in a significant reduction in coating defects (3.42 ± 2.9%, p < 0.0001; Figure 2K), yielding a more uniform coating. In addition to increased coating uniformity, functionalization of PAMAM with SIL also increased polymer deposition, as characterized via quantification of fluorescent intensity in the final alginate layer (see Figure S3). Given that PAMAM-MDT/SIL exhibits a similar polycationic charge to PAMAM-MDT/GA, the improved coatings formed using the SIL-functionalized PAMAM indicate a role of silane in promoting coating uniformity, when the influence of charge is decreased. The functionalization of PAMAM with both GA and SIL (PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL; Figure 2D&H), which reduced the zeta-potential of the PAMAM by almost 60%, also resulted in improved coatings when compared to those formed using PAMAM-MDT (p = 0.003; Figure 2K), albeit less than those formed using PAMAM-MDT/SIL (p = 0.03). Removal of the silane group of the PEG on this PAMAM (i.e. PAMAM-MDT/GA/PEG) resulted in the complete loss of cLbL deposition for these coatings (Figure 2I), supporting the hypothesis that silane self-assembly was the dominant contributor of uniform cLbL on the pancreatic islet when PAMAM charge was diminished.

Figure 2. Evaluation of impact of PAMAM functionalization on coating features.

Multi-slice fluorescence 3D projection (A-D) and cross-sectional (E-H) images of pancreatic islets after coating with 4 alternating layers of PAMAM (red) and Alg-HyPEG-N3 (green). PAMAM functionalization was varied from: A,E) MDT only (PAMAM-MDT); B,F) MDT and GA (PAMAM-MDT/GA); C,G) MDT and SIL (PAMAM-MDT/SIL); or D,H) MDT, GA, and SIL (PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL). I) Control PAMAM-MDT/GA/PEG with functionalization with PEG only (no silane group). J) Uniformity of coating over multiple islet clusters, e.g. cLbL formed by 4 layers of PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL. K) Quantification of defects in coatings (%). Scale bar: J) 100 μm; A-D & I) 50 μm; and E-H) 10 μm. ****p < 0.0001; **p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc.

Other modifications on the GA and SIL functionalized PAMAM, including increasing the GA functionalization from 30 to 50 (ζ-potential = 5.92 ± 0.41 mV) or increasing the length of SIL linker from 2 to 10 kDa, resulted in impaired cLbL formation (data not shown). Islet coating results, as well as PAMAM particulate analysis (Table 1), support the hypothesis that the silane end group on the PAMAM mediates dendrimer-dendrimer interactions into self-assemblies/aggregates. These particle-particle interactions are likely mediated via inter-silanol hydrogen bonding and condensation into Si-O-Si bonds, as reported for similar systems using nanoparticles for other applications.(26)

In our previous work, a strong correlation between polycationic charge and coating uniformity was measured, as characterized by decreasing the net PAMAM charge via GA functionalization. Similar trends were observed herein, with loss of coating features when a poorly cationic PAMAM was used (i.e., PAMAM-MDT/GA/PEG). The inclusion of SIL groups onto the PAMAM, however, recovered cLbL formation onto the islet surface.

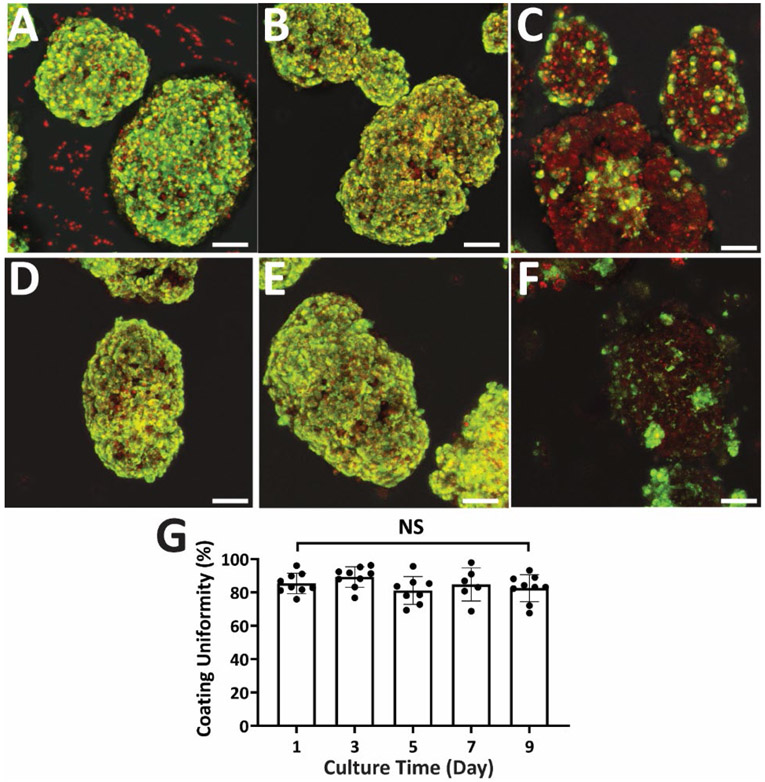

cLbL Coating Stability

Unlike coatings based on electrostatic interactions or cell membrane integration, a covalent layer-by-layer approach has the potential to provide a more durable coverage of the viable organoid. To investigate the stability of our cLbL coatings, islets were cultured for up to 9 days post-encapsulation. As shown in Figure 3, PAMAM-MDT/GA and PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL based coatings were detected on islets after a week in culture. This was in stark comparison to coatings generated using PAMAM-MDT/GA coatings without SIL functionalization. Image quantification of islet coatings illustrated high stability, with no significant change in coating uniformity for the duration of the study (Figure 3G). Temporal tracking of islet morphology, size, and number via light microscopy measured no significant changes during the culture period, even when compared to uncoated islets (Figure S4).

Figure 3. cLbL coatings on pancreatic islets exhibited high stability in culture.

Representative multi-slice fluorescence 3D projection images of islets coated with 4 alternating layers of PAMAM (red) and Alg-HyPEG-N3 (green) at 1 day (A-B) and 7 days (D-F) post-encapsulation. Coatings were formed using: PAMAM-MDT/SIL (A&D); PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL (B&E); or PAMAM-MDT/GA/PEG (C&F). Green = Scale bar = 50 μm. (G) Percent coverage of 4-layer islet coatings formed using PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL as a function of in vitro culture time.

In comparison to other LbL approaches, covalent layer-by-layer assembly using dendrimeric and hyperbranched alginate polymers provides an effective and stable approach. Although efficient islet coverage can be attained through electrostatic-based interactions between opposite charged polymers, it has been widely reported that polycations can impart morphological damage to the cell surface.(15, 27-31) Multiple approaches have sought to mitigate these effects, from grafting the polycation with PEG or membrane anchors to pre-coating the islet via PEGylation or Ca2+.(15, 27, 32-33) Electrostatic layer formation is also inherently unstable, a feature exacerbated within a physiological environment. The use of chemoselective handles permit covalent stabilization between layers, a feature that improves coating stability. An additional benefit of intra-layer stability is that it serves prevents the intra-layer mobility observed in electrostatically generated coatings, which results to the exposure of the poorly biocompatible polycations to the host.(17-19, 34) Finally, the incorporation of biorthogonal ligation schemes offers the advantage of further surface functionalization.(35)

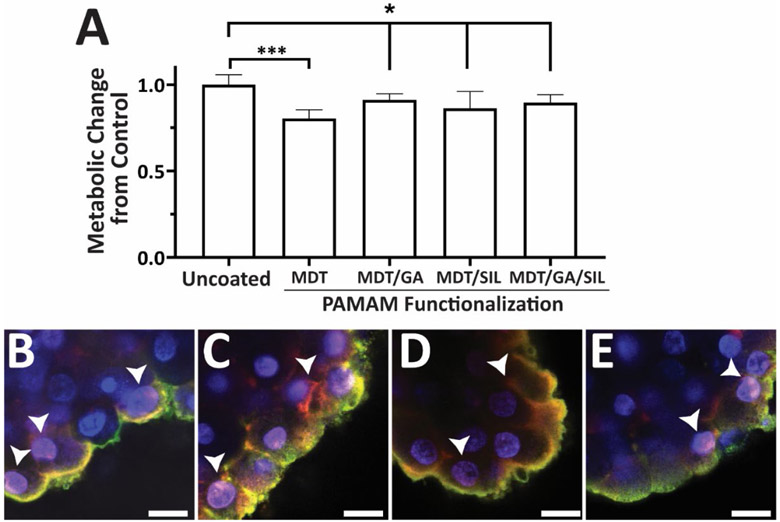

Islet viability and functionality

The global impact of cLbL coatings on the underlying pancreatic islet was first evaluated via quantification of metabolic activity. As summarized in Figure 4A, the overall metabolic activity of the pancreatic islets was moderately affected on day 1 after coating, with modulation of impact based on the type of PAMAM employed. When the strongly polycationic PAMAM-MDT was used in coatings, the metabolic activity was significantly reduced by 19.7% (p = 0.0004; t-test), as previously reported. (20) When PAMAM-MDT/GA, PAMAM-MDT/SIL, or PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL was employed, the decline was more moderate, albeit significant, when compared to untreated controls, with reduction in metabolic activity of 8.9, 13.7, and 10.4%, respectively. After 5 days in culture, the impact of the coating was further mitigated, with no change in metabolic activity for any of the coating groups (Figure S5). Thus, the improved coating uniformity of PAMAM-MDT/SIL and PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL-based cLbL did not impart negative effects on the metabolic activity of the encapsulated cells.

Figure 4. PAMAM-based cLbL coatings impart minimal changes in islet metabolic activity but infiltrate the islet periphery.

A) Metabolic activity, per MTT assay, for uncoated and 4-layer coated islets as a function of PAMAM functionalization. Measurements were made 1 day after coating. B-E) Representative cross-section confocal images of islets coated with 4 alternating layers of PAMAM (red) and Alg-HyPEG-N3 (green) with layers formed using: PAMAM-MDT (B); PAMAM-MDT/GA (C); PAMAM-MDT/SIL (D); PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL (E). Arrows indicate areas of PAMAM infiltration into the cell or interstitial space. Scale bar = 15 μm.

To further characterize the impact of PAMAM coatings on the islet organoid, additional confocal imaging was performed. High magnification cross-sectional imaging of cLbL on pancreatic islets observed polymer coatings primarily relegated to the outer periphery of the islet; however, selected peripheral cells exhibited co-staining of Hoechst (blue, nuclei staining) and Rox (red, PAMAM label) of their nuclei, indicating permeation of the PAMAM polymer into these peripheral cells, regardless of the PAMAM functional groups (Figure 4B-E). Infiltration of these nanoscale dendrimers was not unexpected, given their well-documented use in non-viral drug delivery.(36) PAMAM infiltration mechanisms vary from passive to active (e.g., endocytosis) uptake, depending on PAMAM size, charge, and surface functionalization.(37) While limited to a single cell layer, cellular infiltration of G5 PAMAM dendrimers may not be desirable, as PAMAM-mediated cell death and dysfunction via cell membrane disruption and DNA and/or mitochondrial damage has been reported.(37) PAMAM cytotoxicity can be modulated, however, via optimization of PAMAM features (e.g., size, amine groups, generation number, and dosage).(38-39) For example, PAMAM functionalization with MDT, GA, and SIL resulted larger dendrimer sizes and decreased charge, which may have decreased infiltration and subsequent cytotoxicity. Further exploration of the features of these PAMAM that modulate cytotoxicity is an area of future research. Overall, with moderate declines in total cellular metabolic activity following cLbL coating using these PAMAM derivatives, it is postulated that the integration of PAMAM within this outer cell layer contributed to these declines.

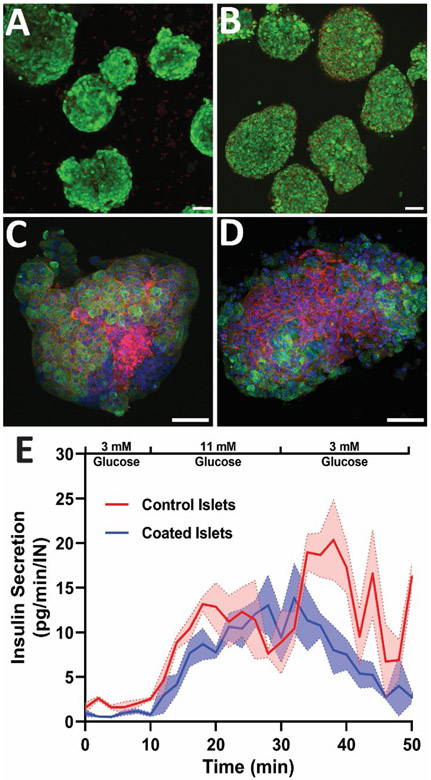

The impact of PAMAM/Alg coatings on islet function was further investigated via additional cellular assessments of islets coated using the PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL variant. As summarized in Figure 5, cLbL islets coated with 4 layers of PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL and Alg-HyPEG-N3 exhibited moderate impacts in overall live/dead viability, morphology, and functionality, when compared to untreated controls. Specifically, highly viable cells were observed throughout the 3D spheroids, but the outer cell periphery of the cLbL islets (Figure 5B) exhibited an increased number of dying (red) cells when compared to uncoated controls (Figure 5A). Whole-mount immunohistochemistry staining for insulin and F-actin on islets encapsulated within PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL and alginate layers detected highly insulin-positive beta cells throughout the islet cluster, but a modest decline in F-actin staining at the outer periphery islet when compared to uncoated controls (Figure 5C-D). This decline may be the result of PAMAM-mediated disruption of the integrity of tight junctions between the pancreatic cells, as previously reported for other cell types.(40) Since actin dynamics correlate with mitochondrial function, cellular ATP/ADP ratios, apoptosis, and insulin secretion regulation in beta cells, remodeling of F-actin due to PAMAM dendrimer integration could lead to decreased cell viability and function.(41-42) Quantification of islet functional activity, however, indicated that these peripheral cell disruptions did not result in significant impairment in glucose-stimulated insulin release of the islets. When subjected to stimulatory glucose levels, a prompt insulin response was observed for both uncoated and PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL cLbL islets (Figure 5E). No notable delay in insulin secretion was measured for coated islets, as characterized by comparing the insulin release slopes of uncoated and coated islets following exposure to stimulatory glucose levels (p = 0.94). Peak insulin release during the stimulatory glucose phase was also similar between the two groups (p = 0.79). Equivalent dynamic insulin stimulation kinetics highlights the benefits of nano-scale layers in retaining efficient glucose sensing and insulin release, a feature that is lost at micro-meter hydrogel encapsulation scales.(43) Following a return to non-stimulatory glucose levels, cLbL islets exhibited a steady decline to basal insulin release levels; however, uncoated islets exhibited oscillatory insulin release during this non-stimulatory phase. Delayed return to original basal insulin release levels following glucose stimulation may indicate islet stress.(44-45) Trends from glucose perifusion studies were further validated using static glucose stimulation, as summarized in Figure S6.

Figure 5. Summary of impacts of cLbL coatings on pancreatic islet viability, morphology, and function on uncoated control islets or islets coated with 4-layers of PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL and Alg-HyPEG-N3.

(A-B) Fluorescent confocal 3D projection of live (green) and dead (red) staining on uncoated control (A) or coated (B) islets. C-D) Whole mount immunohistochemistry imaging of insulin (green), f-actin (red), and nuclei (blue) uncoated control (C) or 4-layer coated (D) islets. Scale bar = 50 μm E) Dynamic glucose stimulated insulin release for uncoated control (red) and 4-layer coated (blue) islets. Legend at top of the graph indicates the glucose concentrations of the bathing media.

The lack of correlation between peripheral cell death and overall glucose responsiveness of the beta cell may be attributed to the unique cytoarchitecture of rodent islets, where a beta cell core is peripherally encased by alpha and delta cells. (46) Future work investigating cLbL coatings on pancreatic islets sourced from different species with variable cytoarchitecture (e.g. human and porcine) would permit further elucidation of this effect. Overall, islets assessments indicate that decreasing the net positive charge of the PAMAM, while promoting PAMAM aggregation via silanization, resulted in a moderate impact on these islet organoids.

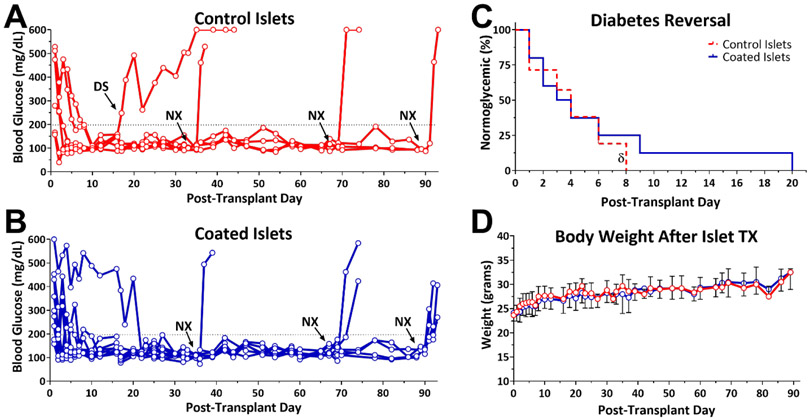

Xenograft Transplants

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of cLbL islets to engraft and function in vivo, islets coated with 4 layers of PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL and Alg-HyPEG-N3 were transplanted into the kidney capsule of chemically-induced diabetic NOD-SCID mouse recipients. Normoglycemia in recipient mice was efficiently established for both cLbL coated and untreated rat islets (Figure 6), with a statistically equivalent time to reversal of 3 ± 3 and 5 ± 6 days, respectively (p = 0.48; t-test). Furthermore, transplant efficacy for recipients of coated islets showed no significant difference compared to mice receiving control islets, per the log-rank test (p = 0.18; Figure 6C) and repeated measure analysis found no significant difference in blood glucose stability between coated and uncoated islets (p = 0.85) for the duration of the study (> 90 days). The body weight of the recipient animals increased by 25 ± 9 % over the course of the study, with no significant difference in weight gain between groups (p = 0.38; two-tail t-test; Figure 6D). Following the retrieval of the graft-bearing kidney at designed time points in a survival surgery, all mice reverted to the diabetic state, validating the stability of the disease state and the potency of the graft.

Figure 6. Equivalent functional efficacy of untreated control islets and islets coated with 4-layers of PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL and Alg-HyPEG-N3.

A-B) Nonfasting blood glucose levels of diabetic NOD-SCID mice following the implantation of uncoated control (A; n = 6) or 4-layer coated islets (B; n = 9) demonstrate long-term function of both transplants. NX = survival nephrectomy of graft bearing kidney; DS = destabilized graft. C) Summary of time to normoglycemia for both groups. δ = functional graft within control group destabilized after 4 days. D) Body weight of diabetic recipients, post-transplant.

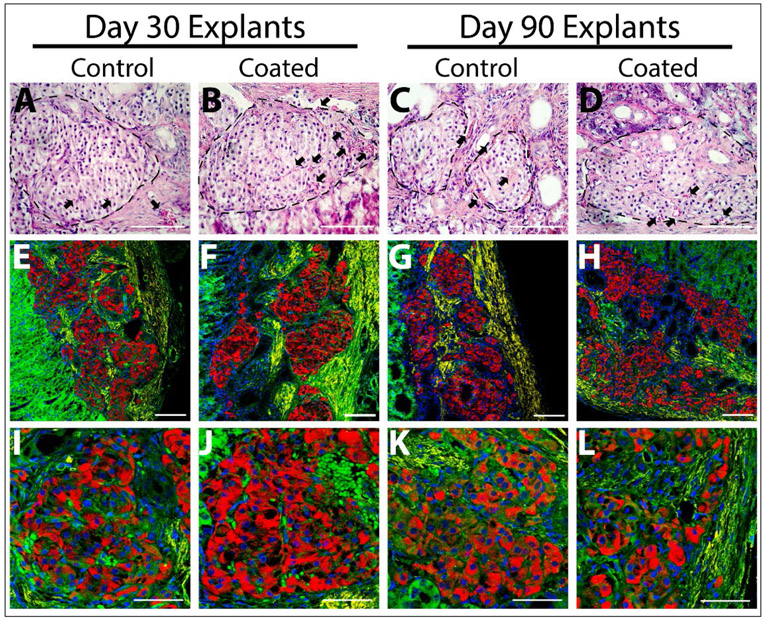

While NOD-SCID mice lack adaptive immunity, innate immune cells that contribute to foreign body responses are retained in this animal model. Time-course histological analysis of coated and control islets grafts was performed on grafts at day 3, 30, 70, and 90 post-transplantation (Figure 7). For both groups, explanted grafts exhibited preserved islet cytoarchitecture and insulin-positive cells, with no discernible difference between coated and uncoated islets. All grafts illustrated host cell remodeling within the kidney subcapsular space over the transplant period. However, no distinct difference in cellular or matrix deposition at the islet interface between the two groups was observed, as characterized via H&E (Figure 7) and Masson’s Trichrome staining (Figure S7). These results indicate that the PAMAM coatings did not alter innate immune cell responses in this rodent model. Of interest, red blood cells (RBCs) were identified in the peri-islet space, with selected presence in the intra-islet space, indicating revascularization of the implanted islets. Positive α-SMA IHC staining was also observed at the periphery of both coated and uncoated islets, indicating mature blood vessel formation and graft vascularization.(47)

Figure 7. Histological analysis of explanted grafts after 30 and 90 days post-transplantation.

A-D) H&E staining of control (A&C) and coated (B&D) islets after 30 (A-B) or 90 days (C-D) post-transplant. RBCs (black arrow) are observed in the periphery and within explanted islets (outlined with a black dotted line). Scale bar = 100 μM. E-L) Lower (E-H) and higher (I-L) magnification imaging of immunohistochemistry staining of explanted control (E, G, I, & K) and coated (F, H, J, & L) islets for insulin (red), α-SMA (yellow), F-actin (green), and DAPI (blue). E-H) Scale bar = 100 μM; I-L) Scale bar = 50 μM.

The overall biocompatibility of these coatings is highly promising, as foreign body responses to the encapsulating material correlate with poor transplant outcomes.(48) The biocompatibility of biomaterial coatings is dependent on numerous factors, such as material properties, scale, and impurities. One significant instigating feature is charge, where cationic polymers induce aggressive foreign body responses.(49) Thus, the lack of a negative host response to the cLbL coated islets indicates that either the decreased charge of the PAMAM-MDT/GA/SIL or the stable covalent binding of the hyper-branched alginate to the outer layer resulted in a neutral cell-host interface.(50)

These murine transplant studies establish the capacity of PAMAM coated islets to restore euglycemia in a diabetic murine model at a therapeutic dosage equivalent to uncoated islets. These results further indicate that the modest declines in overall islet metabolic activity observed in vitro did not translate to discernable impacts in vivo. Our results also demonstrate the capacity of nanoscale encapsulation to achieve normoglycemia in a manner similar to uncoated islets and within transplants sites non-supportive of microencapsulation approaches. The efficacy of these highly stable covalent layer-by-layer coating results are similar to previously published reports using electrostatic, hydrogen-bonded, and biotin-strepavidin based layer-by-layer coatings.(27, 51-52) The functional equivalence of coated and control transplants highlight the capacity of nano-scale coatings to deliver therapeutic effects without requiring additional cell dosages, as commonly encountered when transplanting micro- or macro-encapsulated grafts. In addition, the scale of these coatings permit implantation of islets within confined sites, such as the kidney capsule. It is anticipated, given the limited additional volume imposed by the cLbL coatings, that this coating approach can be used for islets infused into the intrahepatic clinical islet transplantation site, thus elevating the utility of this approach.(3) With these promising results, the next phase of work will examine the immunoprotective capacity of these PAMAM-based coatings by screening cLbL coated islets in allogeneic and autoimmune transplant models.

Conclusions

Silanol functionalization of PAMAM dendrimers enhanced coating uniformity and surface accumulation onto pancreatic islets, resulting in improved covalent layer-by-layer conformal coatings when compared to non-silanol functionalized controls. While peripheral integration of the dendrimer was observed, functional impacts were minimal, with equivalent efficacy of transplanted islets in a diabetic mouse model. This report illustrates the benefits of promoting molecular interaction-driven self-assembly of polymers during covalent layer-by-layer formation. Resulting multifunctional conformal coatings can be further leveraged in future work to characterize their immunoisolating and immunomodulating impact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant DK100654. Mr. Abuid was supported by a T32 Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Type 1 Diabetes and Biomedical Engineering Predoctoral Training Grant (DK108736-02).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Supplementary figures referenced in the main manuscript (Figures S1 to S7) are listed in the Supporting Information

References

- 1.Jacobson AM; Braffett BH; Cleary PA; Gubitosi-Klug RA; Larkin ME; Group, D. E. R., The long-term effects of type 1 diabetes treatment and complications on health-related quality of life: a 23-year follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications cohort. Diabetes Care 2013, 36 (10), 3131–8. DOI: 10.2337/dc12-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantarelli E; Piemonti L, Alternative transplantation sites for pancreatic islet grafts. Current diabetes reports 2011, 11 (5), 364–74. DOI: 10.1007/s11892-011-0216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro AMJ; Pokrywczynska M; Ricordi C, Clinical pancreatic islet transplantation. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2016, 13, 268 DOI: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro AM; Ricordi C; Hering BJ; Auchincloss H; Lindblad R; Robertson RP; Secchi A; Brendel MD; Berney T; Brennan DC; Cagliero E; Alejandro R; Ryan EA; DiMercurio B; Morel P; Polonsky KS; Reems JA; Bretzel RG; Bertuzzi F; Froud T; Kandaswamy R; Sutherland DE; Eisenbarth G; Segal M; Preiksaitis J; Korbutt GS; Barton FB; Viviano L; Seyfert-Margolis V; Bluestone J; Lakey JR, International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med 2006, 355 (13), 1318–30. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrack AL; Martinov T; Fife BT, T Cell-Mediated Beta Cell Destruction: Autoimmunity and Alloimmunity in the Context of Type 1 Diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2017, 8 (343). DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakata N; Sumi S; Yoshimatsu G; Goto M; Egawa S; Unno M, Encapsulated islets transplantation: Past, present and future. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2012, 3 (1), 19–26. DOI: 10.4291/wjgp.v3.i1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez-Pujana A; Santos E; Orive G; Pedraz JL; Hernandez RM, Cell microencapsulation technology: Current vision of its therapeutic potential through the administration routes. J Drug Deliv Sci Tec 2017, 42, 49–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.jddst.2017.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan AJ; O'Neill HS; Duffy GP; O'Brien FJ, Advances in polymeric islet cell encapsulation technologies to limit the foreign body response and provide immunoisolation. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2017, 36, 66–71. DOI: 10.1016/j.coph.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan R; Alexander M; Robles L; Foster CE 3rd; Lakey JR, Islet and stem cell encapsulation for clinical transplantation. Rev Diabet Stud 2014, 11 (1), 84–101. DOI: 10.1900/RDS.2014.11.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buder B; Alexander M; Krishnan R; Chapman DW; Lakey JR, Encapsulated islet transplantation: strategies and clinical trials. Immune Netw 2013, 13 (6), 235–9. DOI: 10.4110/in.2013.13.6.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster GA; Garcia AJ, Bio-synthetic materials for immunomodulation of islet transplants. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017, 114, 266–271. DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teramura Y; Iwata H, Bioartificial pancreas microencapsulation and conformal coating of islet of Langerhans. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2010, 62 (7-8), 827–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozlovskaya V; Xue B; Lei W; Padgett LE; Tse HM; Kharlampieva E, Hydrogen-Bonded Multilayers of Tannic Acid as Mediators of T-Cell Immunity. Advanced healthcare materials 2015, 4 (5), 686–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozlovskaya V; Zavgorodnya O; Chen Y; Ellis K; Tse HM; Cui W; Thompson JA; Kharlampieva E, Ultrathin polymeric coatings based on hydrogen-bonded polyphenol for protection of pancreatic islet cells. Adv Funct Mater 2012, 22 (16), 3389–3398. DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201200138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson JT; Cui W; Kozlovskaya V; Kharlampieva E; Pan D; Qu Z; Krishnamurthy VR; Mets J; Kumar V; Wen J; Song Y; Tsukruk VV; Chaikof EL, Cell Surface Engineering with Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Thin Films. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (18), 7054–7064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krol S; Del Guerra S; Grupillo M; Diaspro A; Gliozzi A; Marchetti P, Multilayer nanoencapsulation. New approach for immune protection of human pancreatic islets. Nano letters 2006, 6 (9), 1933–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King A; Sandler S; Andersson A, The effect of host factors and capsule composition on the cellular overgrowth on implanted alginate capsules. Journal of biomedical materials research 2001, 57 (3), 374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Vos P; De Haan B; Van Schilfgaarde R, Effect of the alginate composition on the biocompatibility of alginate-polylysine microcapsules. Biomaterials 1997, 18 (3), 273–278. DOI: 10.1016/S0142-9612(96)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tam SK; Bilodeau S; Dusseault J; Langlois G; Hallé JP; Yahia LH, Biocompatibility and physicochemical characteristics of alginate–polycation microcapsules. Acta Biomaterialia 2011, 7 (4), 1683–1692. DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gattas-Asfura KM; Stabler CL, Bioorthogonal layer-by-layer encapsulation of pancreatic islets via hyperbranched polymers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2013, 5 (20), 9964–74. DOI: 10.1021/am401981g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbasi E; Aval SF; Akbarzadeh A; Milani M; Nasrabadi HT; Joo SW; Hanifehpour Y; Nejati-Koshki K; Pashaei-Asl R, Dendrimers: synthesis, applications, and properties. Nanoscale Res Lett 2014, 9 (1), 247 DOI: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paquet O; Salon MCB; Zeno E; Belgacem MN, Hydrolysis-condensation kinetics of 3-(2-amino-ethylamino)propyl-trimethoxysilane. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater 2012, 32 (3), 487–493. DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2011.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pileggi A; Molano RD; Ricordi C; Zahr E; Collins J; Valdes R; Inverardi L, Reversal of diabetes by pancreatic islet transplantation into a subcutaneous, neovascularized device. Transplantation 2006, 81 (9), 1318–24. DOI: 10.1097/01.tp.0000203858.41105.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedraza E; Brady AC; Fraker CA; Molano RD; Sukert S; Berman DM; Kenyon NS; Pileggi A; Ricordi C; Stabler CL, Macroporous three-dimensional PDMS scaffolds for extrahepatic islet transplantation. Cell Transplant 2013, 22 (7), 1123–35. DOI: 10.3727/096368912X657440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenguito G; Chaimov D; Weitz JR; Rodriguez-Diaz R; Rawal SA; Tamayo-Garcia A; Caicedo A; Stabler CL; Buchwald P; Agarwal A, Resealable, optically accessible, PDMS-free fluidic platform for ex vivo interrogation of pancreatic islets. Lab Chip 2017, 17 (5), 772–781. DOI: 10.1039/c6lc01504b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang P; Murase N; Suzuki M; Hosokawa C; Kawasaki K; Kato T; Taguchi T, Bright, non-blinking, and less-cytotoxic SiO2 beads with multiple CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010, 46 (25), 4595–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson JT; Cui W; Chaikof EL, Layer-by-layer assembly of a conformal nanothin PEG coating for intraportal islet transplantation. Nano Lett 2008, 8 (7), 1940–8. DOI: 10.1021/nl080694q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chanana M; Gliozzi A; Diaspro A; Chodnevskaja I; Huewel S; Moskalenko V; Ulrichs K; Galla H-J; Krol S, Interaction of Polyelectrolytes and Their Composites with Living Cells. Nano Letters 2005, 5 (12), 2605–2612. DOI: 10.1021/nl0521219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee DY; Park SJ; Lee S; Nam JH; Byun Y, Highly poly(ethylene) glycolylated islets improve long-term islet allograft survival without immunosuppressive medication. Tissue engineering 2007, 13 (8), 2133–41. DOI: 10.1089/ten.2006.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong S; Leroueil PR; Janus EK; Peters JL; Kober M-M; Islam MT; Orr BG; Baker JR; Banaszak Holl MM, Interaction of Polycationic Polymers with Supported Lipid Bilayers and Cells: Nanoscale Hole Formation and Enhanced Membrane Permeability. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2006, 17 (3), 728–734. DOI: 10.1021/bc060077y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gattás-Asfura KM; Stabler CL, Bioorthogonal layer-by-layer encapsulation of pancreatic islets via hyperbranched polymers. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2013, 5 (20), 9964–9974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teramura Y; Kaneda Y; Iwata H, Islet-encapsulation in ultra-thin layer-by-layer membranes of poly(vinyl alcohol) anchored to poly(ethylene glycol)-lipids in the cell membrane. Biomaterials 2007, 28 (32), 4818–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikravesh N; Cox SC; Birdi G; Williams RL; Grover LM, Calcium pre-conditioning substitution enhances viability and glucose sensitivity of pancreatic beta-cells encapsulated using polyelectrolyte multilayer coating method. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 43171 DOI: 10.1038/srep43171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavalle P; Vivet V; Jessel N; Decher G; Voegel J-C; Mesini PJ; Schaaf P, Direct Evidence for Vertical Diffusion and Exchange Processes of Polyanions and Polycations in Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Films. Macromolecules 2004, 37 (3), 1159–1162. DOI: 10.1021/ma035326h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang EY; Kronenfeld JP; Gattás-Asfura KM; Bayer AL; Stabler CL, Engineering an “infectious” Treg biomimetic through chemoselective tethering of TGF-β1 to PEG brush surfaces. Biomaterials 2015, (67, 20–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eichman JD; Bielinska AU; Kukowska-Latallo JF; Baker JR, The use of PAMAM dendrimers in the efficient transfer of genetic material into cells. Pharmaceutical Science & Technology Today 2000, 3 (7), 232–245. DOI: 10.1016/S1461-5347(00)00273-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox LJ; Richardson RM; Briscoe WH, PAMAM dendrimer - cell membrane interactions. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2018, 257, 1–18. DOI: 10.1016/j.cis.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kukowska-Latallo JF; Bielinska AU; Johnson J; Spindler R; Tomalia DA; Baker JR, Efficient transfer of genetic material into mammalian cells using Starburst polyamidoamine dendrimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93 (10), 4897–4902. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukheijee SP; Lyng FM; Garcia A; Davoren M; Byrne HJ, Mechanistic studies of in vitro cytotoxicity of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers in mammalian cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2010, 248 (3), 259–268. DOI: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yellepeddi VK; Ghandehari H, Poly(amido amine) dendrimers in oral delivery. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4 (2), e1173773 DOI: 10.1080/21688370.2016.1173773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gourlay CW; Ayscough KR, The actin cytoskeleton in ageing and apoptosis. FEMS Yeast Res 2005, 5(12), 1193–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.femsyr.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalwat MA; Thurmond DC, Signaling mechanisms of glucose-induced F-actin remodeling in pancreatic islet β cells. Exp Mol Med 2013, 45, e37 DOI: 10.1038/emm.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buchwald P; Tamayo-Garcia A; Manzoli V; Tomei AA; Stabler CL, Glucose-stimulated insulin release: Parallel perifusion studies of free and hydrogel encapsulated human pancreatic islets. Biotechnol Bioeng 2018, 115 (1), 232–245. DOI: 10.1002/bit.26442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skelin Klemen M; Dolenšek J; Slak Rupnik M; Stožer A, The triggering pathway to insulin secretion: Functional similarities and differences between the human and the mouse β cells and their translational relevance. Islets 2017, 9 (6), 109–139. DOI: 10.1080/19382014.2017.1342022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pi J; Zhang Q; Fu J; Woods CG; Hou Y; Corkey BE; Collins S; Andersen ME, ROS signaling, oxidative stress and Nrf2 in pancreatic beta-cell function. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2010, 244 (1), 77–83. DOI: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabrera O; Berman DM; Kenyon NS; Ricordi C; Berggren P-O; Caicedo A, The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103 (7), 2334–2339. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0510790103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brady A-C; Martino MM; Pedraza E; Sukert S; Pileggi A; Ricordi C; Hubbell JA; Stabler CL, Proangiogenic hydrogels within macroporous scaffolds enhance islet engraftment in an extrahepatic site. Tissue engineering. Part A 2013, 19 (23-24), 2544–2552. DOI: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stabler CL; Li Y; Stewart JM; Keselowsky BG, Engineering immunomodulatory biomaterials for type 1 diabetes. Nature Reviews Materials 2019, 4 (6), 429–450. DOI: 10.1038/s41578-019-0112-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King A; Sandler S; Andersson A, The effect of host factors and capsule composition on the cellular overgrowth on implanted alginate capsules. Journal of biomedical materials research 2001, 57 (3), 374–383. DOI: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Vos P; Hoogmoed CG; Busscher HJ, Chemistry and biocompatibility of alginate-PLL capsules for immunoprotection of mammalian cells. Journal of biomedical materials research 2002, 60 (2), 252–259. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.10060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pham-Hua D; Padgett LE; Xue B; Anderson B; Zeiger M; Barra JM; Bethea M; Hunter CS; Kozlovskaya V; Kharlampieva E; Tse HM, Islet encapsulation with polyphenol coatings decreases pro-inflammatory chemokine synthesis and T cell trafficking. Biomaterials 2017, 128, 19–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kizilel S; Scavone A; Liu X; Nothias J-M; Ostrega D; Witkowski P; Millis M, Encapsulation of pancreatic islets within nano-thin functional polyethylene glycol coatings for enhanced insulin secretion. Tissue Engineering Part A 2010, 16 (7), 2217–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.