Abstract

Introduction

In 2014, the South African government adopted a differentiated service delivery (DSD) model in its “National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases (HIV, TB and NCDs)” (AGL) to strengthen the HIV care cascade. We describe the barriers and facilitators of the AGL implementation as experienced by various stakeholders in eight intervention and control sites across four districts.

Methods

Embedded within a cluster‐randomized evaluation of the AGL, we conducted 48 in‐depth interviews (IDIs) with healthcare providers, 16 IDIs with Department of Health and implementing partners and 24 focus group discussions (FGDs) with three HIV patient groups: new, stable and those not stable on treatment or not adhering to care. IDIs were conducted from August 2016 to August 2017; FGDs were conducted in January to February 2017. Content analysis was guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Findings were triangulated among respondent types to elicit barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Results

New HIV patients found counselling helpful but intervention respondents reported sub‐optimal counselling and privacy concerns as barriers to initiation. Providers felt insufficiently trained for this intervention and were confused by the simultaneous rollout of the Universal Test and Treat strategy. For stable patients, repeat prescription collection strategies (RPCS) were generally well received. Patients and providers concurred that RPCS reduced congestion and waiting times at clinics. There was confusion though, among providers and implementers, around implementation of RPCS interventions. For patients not stable on treatment, enhanced counselling and tracing patients lost‐to‐follow‐up were perceived as beneficial to adherence behaviours but faced logistical challenges. All providers faced difficulties accessing data and identifying patients in need of tracing. Congestion at clinics and staff attitude were perceived as barriers preventing patients returning to care.

Conclusions

Implementation of DSD models at scale is complex but this evaluation identified several positive aspects of AGL implementation. The positive perception of RPCS interventions and challenges managing patients not stable on treatment aligned with results from the larger evaluation. While some implementation challenges may resolve with experience, ensuring providers and implementers have the necessary training, tools and resources to operationalize AGL effectively is critical to the overall success of South Africa’s HIV control strategy.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, adherence guidelines, differentiated Care, HIV, counselling, repeat prescription collection strategies

1. Introduction

South Africa has the largest HIV treatment programme in the world, with 4.7 million public sector patients on treatment and a target of 6.1 million patients by end December 2020 [1]. Data indicate that retention in care and adherence to ART in South Africa is poor [2, 3, 4], with just over 70% of patients starting ART retained in care 12 months later [5]. Rates of viral load suppression are also below the targeted 90% of those on treatment across many districts and facilities [6, 7]. Strategies for early initiation of ART and innovative approaches to treatment adherence are critical as the country’s HIV treatment programme continues to expand [8].

To achieve UNAIDS 90‐90‐90 global HIV targets, countries across sub‐Saharan Africa are developing and scaling up differentiated service delivery (DSD) models for providing antiretroviral treatment (ART) [9, 10, 11, 12]. These targeted, patient‐centred service delivery approaches allow services to be adapted to different patient groups to enable better access to, and outcomes of treatment services, and to increase clinic capacity. In 2015, the South African National Department of Health (NDOH) began implementing the “National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases (HIV, TB and NCDs)” (AGL) which outline the provision of a minimum package of eight interventions aimed at improving health outcomes along the cascade of care, including linkage to and retention in care and adherence to treatment [13]. In partnership with the NDOH, we conducted an evaluation of five AGL interventions at 12 “early learning” sites to determine whether the AGL interventions were effective in achieving expected outcomes, and to understand the implementation process. The evaluation found that the interventions targeted at stable patients were successful in maintaining suppression and improving retention outcomes among patients [14]. Interventions targeting newly initiated patients or patients not stable on treatment, however, showed little or no improvement in outcomes compared to the standard of care [14, 15]. These findings indicate a need for gaining a better understanding of the AGL implementation through qualitative research. This paper does not present outcomes, rather qualitatively describes the strengths and challenges of the AGL implementation as experienced by health providers, patients and implementing partners in four intervention and four control sites.

2. Methods

2.1. Description of the intervention

The AGL, developed in 2014, was piloted in 12 early learning sites starting in 2015 in four districts by the government and implementing partners, in order to further inform the national AGL scale up [13]. Provincial governments and implementing partners, typically international or local non‐governmental organizations (NGOs), collaborated to operationalize this guideline across provinces and districts [16]. The AGL interventions target four groups of patients with HIV, those who: (1) are newly testing and initiating treatment (new patients); (2) have initiated treatment and achieved viral load suppression (stable patients); (3) have initiated treatment and have elevated viral loads or missed their schedule for clinical care (patients not stable on treatment); and (4) children and adolescents living with HIV (Table 1) as well as one intervention that focused on facility infrastructure and the provision of integrated care. This evaluation includes only those interventions focused on adults (given the limited scope, of the evaluation we did not include children and adolescents) and excludes the facility infrastructure intervention. The primary intervention targeting new patients is fast track treatment initiation counselling (FTIC). Repeat prescription collection strategies (RPCS), which includes Adherence Clubs (both in and outside of facilities) and decentralized medication delivery (DMD) where medications are delivered to and collected from external pick up points, target stable patients with suppressed viral loads. Enhanced adherence counselling (EAC) and early tracing interventions (TRIC) target those patients not stable on treatment with unsuppressed viral loads or who have missed visits.

Table 1.

South Africa’s National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases: approach, interventions and standard of care for each patient groups

| Target patient type | Adherence guideline (AGL) intervention [13] | Description of AGL intervention in study districts | Standard of care intervention | Description of standard of care in study districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New patients: Newly testing and initiating treatment | Fast track treatment initiation counselling (FTIC) | Standardized education, counselling, and adherence support for newly diagnosed patients without delaying treatment initiation, and patient assistance to develop their own adherence plan. Patients initiate treatment after the first counselling session and complete remaining sessions at the first and second refill | 2015 ART guidelines (NDOH) [13]; Universal Test and Treat (UTT) (from Sept 2016) [17] | Fast‐track initiation for certain patients based on health conditions including pregnant or breastfeeding women, or patients with CD4 ≤ 200 or stage 4 HIV; Start ART as soon patient is ready and within two weeks of CD4 count, regardless of CD4 result or HIV stage |

| Patients stable on treatment: Have initiated treatment and achieved viral load suppression (2 consecutive viral loads <400 copies/mL) | Repeat prescription collection strategies (RPCS) | Clinic‐based Adherence Clubs (AC): Patients receive medication and care during small group meetings (<30) conducted at the clinic or in the community every two months | Community‐based Adherence Clubs (AC) (Implemented as early as 2012) [21] | Implemented in some parts of the country via non‐governmental organizations. Patients receive medication and care during bi‐monthly small group meetings (<30) conducted at a clinic or in the community |

| Decentralized medication delivery (DMD): Medications picked up at an external pick‐up‐point every two months | Decanting strategy (from May to June 2016) [14] | Promoted DMD and ACs in effort to decongest clinics. Included only the RPCS from the AGL; no formal launch. Rolled out at other non‐study sites within the study districts | ||

| Spaced fast lane appointment systems (SFLA): Medication collected every two months from a dedicated fast‐lane pick‐up point at the facility with appointment for pick‐up date | 2015 ART guidelines (NDOH) [13] | Support groups, SMS reminders, peer support worker, buddy system, community outreach with medication pick‐up at the facility | ||

| Patients not stable on treatment: Have initiated treatment and have an elevated viral load or missed scheduled clinic visit | Enhanced adherence counselling (EAC) | Enhanced adherence monitoring and targeted counselling interventions for those patients not stable on treatment (as defined by an elevated viral load) with timeous referral for support | 2015 ART guidelines (NDOH) [13] | Increased counselling efforts, home visits, social support emphasis (buddy and support group), pill counts |

| Early tracing of all missed appointments (TRIC) | Telephonic tracing and home visits by community health workers to trace patients who have failed to return to the facility for scheduled appointments by five days or more | 2015 ART guidelines (NDOH) [13] | Telephonic tracing and home visits by CHWs to trace patients who have failed to return to the facility for a scheduled visit by 14 days or more |

The AGL guidelines include interventions focused on children and adolescents living with HIV and an integrated care model of patients with chronic conditions.

NDOH staff at district and provincial level, supervised implementation supported by district implementing partners. Each district had at least two partner NGOs supporting AGL implementation [19]. Study staff were not involved in implementation.

2.2. Study setting and design

A cluster‐randomized evaluation of the AGL interventions was conducted in 12 health facilities implementing the minimum package of interventions (intervention sites) and in 12 health facilities with delayed AGL implementation (control sites – where implementation of the minimum package of interventions was delayed until scaled‐up in the national rollout) [20]. These sites are located in one district in each of four provinces, representing a range of district profiles in terms of rurality, levels of employment, HIV testing coverage and adherence monitoring (Table S1). Methods and results of the trial are described elsewhere [14, 20].

Nested within the cluster‐randomized evaluation, we conducted a hybrid inductive‐deductive qualitative sub‐study among a sample of patients, providers and implementing partners at one intervention and one control site in each district. The sites were purposively selected from the 24 matched intervention and control sites included in the larger evaluation (the matching of sites is described elsewhere) [20]. In each district the intervention site that first implemented the AGL interventions was selected for this qualitative study along with its matched control site. Semi‐structured in‐depth interviews (IDIs) with health providers and implementers and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with patients were done to better understand facilitators and challenges of implementing AGL interventions [21]. We report findings of this study using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research reporting guidelines [22].

2.3. Analytic framework

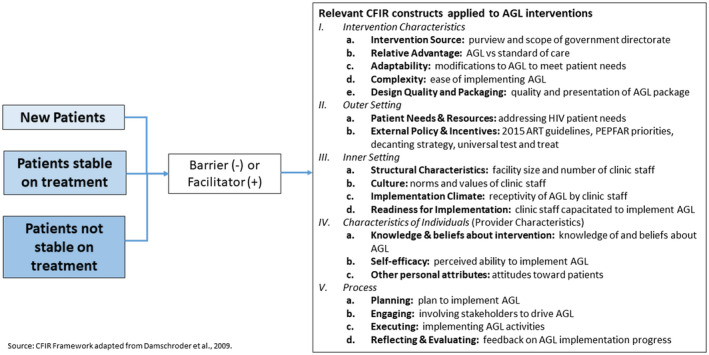

Implementation science approaches are critical to understand the mechanisms that underlie the effectiveness of complex programmes [23, 24]. We used salient constructs from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to guide the evaluation, including the design of the data collection instruments and analysis. CFIR categorizes 39 implementation constructs under the main domains of: (1) intervention characteristics (quality, adaptability, complexity); (2) outer setting (patient needs, setting, policies); (3) inner setting (organizational priority, implementation climate, leadership engagement); (4) individual provider characteristics (knowledge about interventions, self‐efficacy, identification with organization) and; (5) process (planning, engaging, executing and evaluating) [25, 26, 27].

Figure 1 illustrates how we linked responses about AGL interventions to constructs in the CFIR (Figure 1) in order to guide and organize our interpretation of results. For example if a patient not stable on treatment perceived that EAC had more benefits than previous counselling, it would be coded under EAC and then as positive under “Relative Advantage,” because the respondent regarded the intervention as better than the standard of care.

Figure 1.

Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to evaluate the National Adherence Guidelines interventions for new patients, patients stable on treatment and those patients who are not stable on treatment.

2.4. Study sample

FGDs were conducted among three groups of patients at each of the eight study sites: (1) recently initiated treatment; (2) stable on treatment 12 months after initiation (defined by two consecutive viral loads that were undetectable and (3) not stable on treatment ≥3 months after initiation (defined by an unsuppressed viral load >400 copies/mL) or who had missed a visit by more than five days). Patients receiving the interventions (intervention sites) or those eligible to receive them (control sites) were identified from the records from the larger evaluation and invited to enrol in FGDs. Decentralized medicine delivery (DMD) management fell under the purview of a different government directorate than the other AGL interventions and consequently randomization of this strategy could not be preserved. Some control sites implemented DMD and some intervention sites did not. Where possible, we attempted to select stable FGD participants unexposed to DMD at control sites by confirming exposure prior to enrolment. The number of FGDs was determined a priori to provide a sufficient sample to reach thematic saturation [28, 29].

We conducted IDIs with a purposive sample of six providers per site responsible for implementing AGL or standard of care (e.g. lay counsellors, nurses, pharmacists, clinic operations managers and non‐clinical staff such as community health workers, data capturers and administrative clerks) and always the Clinic/Operations Manager. Four of the key implementing partner respondents in each district were purposively selected to be interviewed. Implementing partner respondents included district Department of Health (DOH) managers, technical experts and managers from partner NGOs. The number of provider interviewers per site was determined a priori to provide a sufficient sample to reach thematic saturation [28, 29]. The number of partners was selected to ensure representation from key implementing organizations.

2.5. Data collection and instrumentation

Data were collected November 2016 to October 2017 to allow patients enrolled in AGL interventions sufficient time to experience the interventions and to ensure that patient interaction for this sub‐study did not influence outcomes in the larger effectiveness evaluation. FGD guides were designed to elicit patient perspectives on: (1) quality and acceptability of interventions; (2) barriers to and facilitators of patient treatment adherence; (3) satisfaction and appropriateness of adherence services and (4) ways to improve the interventions. Semi‐structured IDI guides captured domains of effectiveness, patient‐centred/acceptability, accessibility, efficiency and equity. FGDs lasted between 53 and 129 minutes and IDIs 30 to 60 minutes.

2.6. Data management and analysis

All FGDs and all but one IDI were audio recorded, recordings were transcribed verbatim into the original local language and then translated and transcribed into English. Transcripts were checked for mistakes to improve reliability, then imported into NVivo 11© (Doncaster, Australia), coded line‐by‐line and analysed using a content analysis approach [30]. Data analysis and interpretation was guided by the CFIR framework and stratified by AGL intervention patient type (new, stable, not stable on treatment) (Figure 1). Codes were identified a priori and additional codes were included as they emerged. To minimize researcher bias and reflexivity, two researchers coded each transcript, inter‐coder agreement was assessed using a Kappa coefficient, and coding was refined until agreement reached good correlation (>0.5). Findings were triangulated and contextualized with findings from the larger evaluation [14, 20].

Demographic data are presented for all respondent types. FGD and IDI results are presented in role‐ordered matrices with supporting illustrative quotes, stratified by intervention and control and by patient type. Key themes were not different between locations, therefore data are not stratified by site.

2.7. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was granted from the Boston University Institutional Review Board (IRB), (protocol H‐34197), and the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics (Medical) Committee in Johannesburg (protocol M150652). Data collectors were trained in qualitative interviewing techniques, Good Clinical Practice, research ethics and study procedures. We obtained written informed consent from each respondent.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

We conducted 24 FGDs (N = 156). One FGD was conducted with each of the three patient types at each of the eight study sites. Two‐thirds of respondents were between 30 and 49 years old (Table 2). Intervention sites had more female (71% vs. 57%) and slightly more married (28% vs. 22%) participants. A total of 48 providers participated in IDIs, 24 from intervention sites and 24 from control sites. The majority were female (81%) and over half were working as a clinical care provider (Table 2). Half of the 16 implementing partners were DOH staff and half from NGOs. Implementers oversee multiple facilities and are not categorized by study arm.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patient focus group discussion and provider and implementer in‐depth interview respondents from the evaluation of South Africa’s National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Disease

| Patients | Control (N = 74) | Intervention (N = 82) | Total (N = 156) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| Age (n = 156) | ||||||

| 18 to 29 | 14 | 18.9 | 16 | 19.5 | 30 | 19.2 |

| 30 to 39 | 23 | 31.1 | 29 | 35.4 | 52 | 33.3 |

| 40 to 49 | 25 | 33.8 | 27 | 32.9 | 52 | 33.3 |

| 50+ | 12 | 16.2 | 10 | 12.2 | 22 | 14.1 |

| Sex (n = 156) | ||||||

| Female | 42 | 56.8 | 58 | 70.7 | 100 | 64.1 |

| Male | 32 | 43.2 | 24 | 29.3 | 56 | 35.9 |

| Marital status (n = 154) | 73 | 81 | ||||

| Never married | 50 | 68.5 | 49 | 60.5 | 99 | 64.3 |

| Married | 16 | 21.9 | 23 | 28.4 | 39 | 25.3 |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 7 | 9.6 | 9 | 11.1 | 16 | 10.4 |

| Respondents by patient type | ||||||

| Newly initiated treatment | 17 | 23.0 | 22 | 26.8 | 39 | 25.0 |

| Stable on treatment | 35 | 47.3 | 31 | 37.8 | 66 | 42.3 |

| Not stable on treatment | 23 | 31.1 | 29 | 35.4 | 52 | 33.3 |

| Respondents by province | ||||||

| North West | 17 | 23.0 | 19 | 23.2 | 36 | 23.1 |

| Gauteng | 20 | 27.0 | 23 | 28.0 | 43 | 27.6 |

| Limpopo | 20 | 27.0 | 21 | 25.6 | 41 | 26.3 |

| KwaZulu Natal | 17 | 23.0 | 19 | 23.2 | 36 | 23.1 |

| Providers | Control (N = 24) | Intervention (N = 24) | Total (N = 48) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||

| Sex (n = 48) | |||||||||

| Female | 17 | 70.8 | 22 | 91.7 | 39 | 81.3 | |||

| Male | 7 | 29.2 | 2 | 8.3 | 9 | 18.8 | |||

| Current role (n = 48) | |||||||||

| Clinical provider | 13 | 54.2 | 12 | 50.0 | 25 | 52.1 | |||

| Pharmacy staff | 3 | 12.5 | 3 | 12.5 | 6 | 12.5 | |||

| Non‐clinical facility staff | 6 | 25.0 | 7 | 29.2 | 13 | 27.1 | |||

| Outreach | 2 | 8.3 | 2 | 8.3 | 4 | 8.3 | |||

| Median no. of years working with facility/organization (range) | 2.8 (1.0, 19.0) | 3.5 (1.0, 16.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 19.0) | ||||||

| Median no. of years working with in current capacity (range) | 3.5 (1.0, 26.0) | 4.5 (0.0, 21.0) | 4.0 (0.0, 26) | ||||||

| Implementers | Total (N = 16) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | (%) | ||||

| Sex (n = 16) | ||||||

| Female | – | – | 11 | (68.3) | ||

| Male | – | – | 5 | (31.3) | ||

| Current role a (n = 16) | ||||||

| DOH staff | – | – | 8 | (50.0) | ||

| Implementing partners | – | – | 8 | (50.0) | ||

| Median no. of years working with facility/organization (range) | – | – | 4.0 (3.0, 7.0) | |||

| Median no. of years working with in current capacity (range) | – | – | 4.0 (2.0, 27.0) | |||

Roles included CCMDD managers, trainers, technical experts, mentors, managers and coordinators.

3.2. Implementation outcomes

To organize results, key emerging barriers and facilitators by respondent type are illustrated by quotes (Table 3). Key barriers to implementation identified by patients (FGDs), providers and implementers (IDIs) are organized by salient CFIR construct in Table 4 (New patients), Table 5 (Stable patients) and Table 6 (Patients not stable on treatment) in order to facilitate comparison between respondent types. Generally, and not surprisingly, the majority of patient responses fell into the “Process” CFIR domain, as their experience is most impacted by their personal interactions with the interventions. From the providers’ and implementers’ perspectives, however, key barriers to implementation fell primarily within the CFIR domains of “Intervention Characteristics” (i.e. relative advantage and complexity, “Inner Setting” (i.e. readiness for implementation and implementation climate), and to a lesser extent on “Process.” Both FGD and IDI respondents converged on patient needs, particularly for stable patients. Detailed results are summarized below, organized by patient type.

Table 3.

Qualitative responses from a cross‐sectional sample of patients, providers and implementers on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of South Africa’s National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases for new patients, stable patients and patients not stable on treatment or not adhering to care

| Barrier/facilitator | Quote |

|---|---|

| 1. Perspectives on interventions for new patients | |

| Facilitator | a) “…the experience I had with the one that I consulted with is that she went all out to make sure that I was comfortable and I understood what was expected of me as a patient and for my life to change for the better and be right … the female nurse that was assisting me played a motherly role, a champion role to me, I will not forget her.” – New patient, intervention |

| Barrier | b) “… I’m not satisfied yet because I think [fast‐tracking is] one of the things that leads to defaulting because they don’t get time to digest whatever they got today from the clinic. They knew the bad news if I can call it, yes, so they, they don’t understand… We don’t get enough time with them to make them understand, yes.” – Professional nurse, control |

| 2. Perspectives on interventions for patients stable on treatment | |

| Facilitators | a) “The clubs are also assisting, because we no longer experience long queues. This is encouraging, because if you take your treatment consistently, you would ultimately qualify to belong to a club and that’s what we all crave for.” – New patient, intervention |

| b) “We are saying to the patient: patient, you qualify because you are a good patient, there are these three decanting models. We want you to choose the one that suites you. Some are working, she might say she wants the SFLA [Spaced and Fast Lane Appointment] so that ‘I can come in quickly, collect my medication and go’. Some will say ‘I’ve got time, I will still want to come and socialise and be in the AC’, then she will go into that. Some will say, ‘No, no, no. I no longer want to even come into your facility. Let me go and collect it outside’. So, to me, I think it makes the patients to be responsible for their own choices, which is what primary health care says. Self‐actualization and self‐realization, we want them to be responsible for their own. Because if they are then responsible, then it will be easy for them to adhere.” – District‐based Department of Health implementer | |

| Barriers | c) “I was not asked anything. I went to the clinic. When I arrived as usual, they said to me they are taking me out and adding me to the club of which I am happy with it.” – Stable patient, intervention |

| d) “First, training. Second, a champion for each… like a [DMD] champion, or adherence club manager. Someone who’s going to be liable for that programme. So, when you go to a facility you know who to talk to about each problem. But currently when you go to a facility everyone is saying, ‘I don’t know anything about that, it’s not my job, I don’t know anything about that.’ But, if there is a sense of ownership in the facility, we’ll improve the implementation of adherence guidelines.” – Implementing partner | |

| 3. Perspectives on interventions for patients not stable on treatment | |

| Facilitators | a) “We motivate the patients. We motivate them to say, you still have a chance. If you are sick, you still have to come. So we motivate them, and we counsel them. It does work.” – Professional nurse, control |

| b) “In previous cases, we used to do superficial things. Our counsellors now, they have been trained enough. They know that they have to take their time with the client and it’s not in our place to judge them. Because in previous cases, you find like the sister is accusing the client or judging the client. So now at least we have time, we try to understand their problems.” – Professional nurse, intervention | |

| c) “Once [patients who were traced] come to the clinic they become our first priority. We start with taking bloods if there is a need to take bloods. Then we send them back to enhanced counselling, because obviously these people are not compliant.” – Professional nurse, intervention | |

| Barriers | d) “The counsellors do not guide you. Instead of advising you on how you should live a healthy life, they would instead shout at you. You tell them that you are currently stressed up, you are facing this and that problem, they would tell you that you are telling lies, that’s your own excuse, because they don’t know the background you come from.” – Stable patient, control |

| e) “We are having the challenge of tracing the clients. We will find that some of them moved out without coming to the facility and ask for the referral letter or transfer letter. Because most of the people who are on ART are being employed at the nearest farms, and the production there is seasonal.” – Professional nurse, control | |

| f) “I think it’s also dangerous for the people who are tracing, because they tell us that in other places, only maybe a group of men will come out, so it is scary for the care workers. People don’t want their status to be known out there, so if you trace them, others become angry.” – Facility manager, intervention | |

| g) “By having a scanty number of community care givers, sometimes we get in difficult where there are no‐go areas where they can’t reach the other areas. They haven’t got transport, they walk.” – Facility manager, intervention | |

Table 4.

Facilitators and barriers to ART initiation and adherence for new patients eligible for the Fast track Initiation Counselling intervention under the South African National Adherence Guidelines mapped to relevant Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research constructs

| Intervention | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Barriers | Facilitators | Barriers |

|

Intervention characteristics: Design quality

Relative advantage

|

Intervention characteristics: Complexity

Intervention source

Relative advantage

|

Intervention characteristics: Design quality

Relative advantage

|

Intervention characteristics: Complexity

|

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

External policy

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

External policy

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

External policy

|

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

Readiness for implementation

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

Readiness for implementation

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

|

|

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

|

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

Self‐efficacy

|

Characteristics of providers: Knowledge & beliefs

|

Characteristics of providers: Knowledge & beliefs

Self‐efficacy

|

|

Process: Execution

|

Process: Execution

Planning and engagement

|

Process: Execution

|

Process: Execution

|

FGD, focus group discussions with patients; IDI: in‐depth interviews with providers and implementers.

Table 5.

Facilitators and barriers to ART adherence for stable patients eligible for Repeat Prescription Collection Strategies under the South African National Adherence Guidelines mapped to relevant Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research constructs

| Intervention | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Barriers | Facilitators | Barriers |

|

Intervention characteristics: Relative advantage

Adaptability

|

Intervention characteristics: Relative advantage

Design quality

Intervention source

Complexity

|

Intervention characteristics: Relative advantage

Adaptability

|

Intervention characteristics: Relative advantage

Design quality

|

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

|

Outer setting: No codes mapped to this CFIR domain |

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

|

Inner setting: Implementation climate

|

|

Characteristics of providers: No codes mapped to this CFIR domain |

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

|

Characteristics of providers: No codes mapped to this CFIR domain |

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

|

|

Process: Engagement

Execution

Reflection

|

Process: Engagement

Planning and engagement

Execution

|

Process: Execution

|

Process: Engagement

Execution

|

FGD, focus group discussions with patients; IDI, in‐depth interviews with providers and implementers.

Table 6.

Facilitators and barriers to ART adherence for patients not stable on treatment or not adhering to care eligible for Enhanced Adherence Counselling or Early Tracing interventions under the South African National Adherence Guidelines mapped to relevant Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research constructs

| Intervention | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Barriers | Facilitators | Barriers |

|

Intervention characteristics: Relative advantage

|

Intervention characteristics: Complexity

Design quality

|

Intervention characteristics: Design quality

|

Intervention characteristics: Complexity

Design quality

|

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

External policy

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

Cosmopolitanism

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

Peer pressure

|

Outer setting: Patient needs

|

|

Inner setting: Readiness for implementation

Relative priority

Goals and feedback

Culture Providers work with each other to help the patient [IDI] |

Inner setting: Structural characteristics

Challenges with tracing and long wait times at clinic because of staff or resource shortage [IDI] Relative priority

Compatibility

|

Inner setting: Relative priority

Available resources

|

Inner setting: Structural characteristics

Relative priority

|

|

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

Beliefs

Self‐efficacy

|

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

Self‐efficacy

Beliefs

|

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

Beliefs

|

Characteristics of providers: Personal attributes

Beliefs

|

|

Process: Execution

Engagement

Reflection

|

Process: Execution

Reflection

|

Process: Execution

Engagement

Reflection

|

Process: Execution

Reflection

|

FGD, focus group discussions with patients; IDI, in‐depth interviews with providers and implementers.

3.2.1. Perspectives on interventions for patients newly initiated on treatment

Fast Track Initiation and Counselling, which initiated patients on ART after their first counselling session usually during their second clinic visit, was the primary AGL intervention for new patients. The standard of care – the 2015 ART guidelines and Universal Test and Treat (UTT) circular identified priority patients to start ART as soon as possible and within two weeks (Table 1) [13, 17, 31]. Patients in both arms valued knowing their status, supported testing for everyone and found counselling helpful during ART initiation (Table 4). The process of counselling was a major barrier to patients in both arms. Patients valued and desired frequent and substantive counselling, particularly after ART initiation (Table 3; quote 1a), and cited minimal attention from providers and misinformation as barriers to initiation (Table 4). In control sites, patients felt providers were not well informed nor well trained in ART initiation. Intervention respondents reported sub‐optimal counselling and privacy concerns as barriers to initiation.

Providers were sometimes confused between FTIC and UTT, and felt they were insufficiently prepared in terms of training and resources for either intervention. Consistent with patient perspectives, providers perceived pressure from government to rapidly rollout UTT, resulting in insufficient time to adequately prepare patients for initiation (i.e. physically, psychologically or emotionally). Some providers in control sites resisted expediting initiation and would at times deliberately not fast‐track patients without completed laboratory tests or sufficient counselling (Table 3; quote 1b).

3.2.2. Perspectives on interventions for patients who are stable on treatment

Repeat Prescription Collection Strategies (RPCS) including clinic‐ or community‐based adherence clubs (ACs), decentralized medication delivery (DMD), and spaced and fast lane appointment systems (SFLA) were the primary AGL interventions for patients stable on treatment (Table 1). In control sites, adherence interventions implemented for stable patients included ACs and DMD, and interventions detailed in the 2015 ART guidelines (support groups, SMS reminders, buddy system and community outreach) (Table 1) [13, 17]. Because DMD was implemented at some control sites, respondents in both arms reported similar perceptions, and were generally positive about DMD and ACs. (Table 5).

Patients and providers concurred that DMD and ACs reduced queues and waiting times and decongested facilities (Table 3; quote 2a). DMD was especially helpful for employed or time‐constrained patients. Patients in both study arms found DMD easy, though many felt it lacked sufficient adherence support and health monitoring. Most patients in the intervention groups liked the social aspect of ACs, but some found them inconvenient. Others articulated a perception of exclusivity because not all stable ART patients were eligible (e.g. those with high blood pressure or tuberculosis), or were offered the opportunity to participate in ACs. Opinions differed on the process of implementation, specifically whether patients were given a choice of refill strategy. Implementers report it is foundational to offer a choice between RPCSs (Table 3; quote 2b), however, patients in both study arms felt they were not given a choice, and could only opt in or out of the singular RPCS offered to them (Table 3; quote 2c).

Providers and implementers found DMD difficult to manage and reported that medications were not always available for pick‐up when they should have been. Both faced early challenges implementing DMD, citing that: it was not well introduced at AGL initiation trainings with limited provider training on implementation of DMD; and the rollout of a separate strategy (the Decanting Strategy) by a different Department of Health directorate, which promoted just the RPCS interventions, caused further confusion. In addition, there was no clear ownership of the rollout of these interventions, and poor communication between facilities and DMD pick‐up points meant that scripting issues sometimes occurred preventing timely delivery of medications. Providers also found it challenging to monitor DMD patients for adherence, and perceived that patients felt “chased” from the facility, raising concerns about attrition. Suggestions to improve RPCS interventions included additional training, identifying champions and improving ownership of implementation (Table 3; quote 2d).

3.2.3. Perspectives on interventions for patients who are not stable on treatment

The primary AGL interventions for patients not stable on treatment were enhanced adherence counselling (EAC) and early tracing of all missed appointments (TRIC). The 2015 ART guidelines outline increased counselling efforts, home visits, pill counts and an emphasis on social support as the standard of care (Table 1). Overall, patients who are not stable on treatment at intervention sites were aware of the AGL interventions. They believed these approaches could benefit adherence behaviours but perceived crowded clinics and poor staff attitude as barriers (Table 6). Some patients from intervention sites were more positive, suggesting that some providers were helpful and respectful, and listened to patients, and that patient experience at the clinic is largely dependent on which staff are seen. Providers agreed with patients that staff shortages and long queues at the clinic were challenges but also believed good patient–provider relationships facilitate adherence. Providers trained in EAC felt better equipped to counsel patients and, in both arms, enhanced counselling was seen as beneficial when delivered well (Table 3; quotes 3a and 3b).

Tracing emerged as a priority for providers but implementation was a major challenge in both study arms. Providers noted having inaccurate patient contact information (Table 3; quote 3e) and mentioned safety concerns when physically tracing patients; staff shortages; and an inability to access lists of patients requiring tracing (Table 3; quotes 3f, 3g). Control sites mentioned that even when tracing is successful, the clinic is full and patients cannot be seen promptly. Some intervention sites reported prioritizing traced patients (Table 3; quotes 3c).

4. Discussion

South Africa, like other countries in the region, embarked on an effort to make DSD a standard component of the HIV treatment programme. Implementing these models at scale, though, is complicated [32]. We identified a number of positive aspects in the implementation of the AGL in South Africa, but also elicited key challenges. Repeat prescription collection strategies (AC and DMD) were generally perceived positively by all concerned. The opportunity to avoid long queues and quickly pick up medicines, and to benefit from the social interaction and additional counselling and education offered at ACs, were key benefits [33, 34, 35, 36]. Providers generally felt adequately equipped to deliver ACs, likely benefiting from the long‐term experience of Médecins sans Frontiers implementing ACs and the training materials they developed [18, 37, 38]. This positive perspective is consistent with the results of the larger impact evaluation, which showed that patients enrolled in RPCS maintained, and in some cases improved, adherence and retention outcomes [14, 39], and with other evaluations of ACs in South Africa and Kenya [18, 33, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45].

If early implementation successes are to be sustained as the AGL are taken to scale, a number of challenges need to be addressed. Providers expressed confusion around policies with overlapping targets [35]. FTIC was understandably conflated with the concurrent rollout of UTT [46, 47] and the 2015 ART guidelines which also provide guidance for fast‐tracking priority patients [48] given that both require expediting and/or combining counselling sessions to enable same‐day or rapid initiation of ART providers found it hard to make the distinction between these strategies. This unintended consequence underscores the need for clear, consistent communication channels when scaling complex interventions. The RPCS strategies for stable patients were confused with the implementation of the “Decanting Strategy” which promoted DMD and ACs under a separate national agenda [49, 50]. The “Decanting Strategy” was a national directive to decongest clinics and decant stable patients out of facilities resulting in the rollout of these interventions at non‐study sites within the districts [35]. EAC and TRIC are also offered, to some degree, under existing guidelines but prioritize slightly different groups of patients to those identified under the AGL. There was consequently confusion over which strategy should be prioritized and a lack of clarity on how AGL interventions differ from other policies. Providers were uncertain which strategy to implement or how to monitor implementation quality.

The complexity of DSD necessitates extensive and adequate training and support. Providers and implementers frequently felt they were not properly trained or sufficiently equipped to implement effectively across all types of patients, particularly with respect to DMD. Additionally, private pharmacists are an instrumental component of DMD, yet have traditionally not been engaged with public sector care and thus do not understand the intricacies of the DMD intervention. Though patients and providers largely perceived DMD to be beneficial, implementation challenges were seen as a risk to patient adherence and retention if medication was not available as expected [35].

Three main tasks are critical to the national implementation of the AGL intervention: (1) Ensuring providers engaged with DMD receive standardized, comprehensive training and mentorship around cohort creation and scripting; (2) Addressing scripting and medicine supply issues and (3) Providing integrated data systems so all providers can monitor and track patients both at the facility and pick‐up‐point. Expanding the services offered at external care points (both ACs and DMD pick‐up points), such as the ability to draw monitoring bloods, could further improve patient satisfaction and retention [51].

The preferences of HIV patients, such as appointments for clinic visits and medication collection, are an important driver of intervention uptake. Because not all patients were aware they had a choice between RPCS interventions, it is important that providers understand the available RPCS options and facilitate patients to select one that best meets their treatment need. Clear plans should also be in place for patients who transition between interventions to prevent attrition.

Providers faced most logistical challenges implementing EAC and TRIC. Providers underutilized viral load results because they could not access test results or because tests had not been done and those implementing TRIC did not have the lists of patients to contact or the resources to trace patients. These issues might be addressed by integrating data and coordinating resources between implementing partners and facilities. These results are aligned with the results of the larger evaluation which showed little difference in terms of suppression and retention outcomes between the intervention and control sites probably because there was little difference in the interventions that were implemented at each site [15]. Effectively managing patients not stable on treatment is critical to the broader HIV control strategy, but at the early learning sites, providers and implementers did not have the necessary training, tools, resources or support to do so.

Patients in all groups wanted more frequent and better quality counselling [34]. Similarly, providers were reluctant to implement FTIC, which should reduce the number of pre‐initiation counselling sessions, suggesting they felt patients were not ready for treatment initiation or that they were not comfortable initiating patients without completing counselling sessions. This demonstrated a lack of understanding about the FTIC counselling sessions and the continued counselling after initiation highlights the need for comprehensive AGL training within the context of multiple policies, strategies and guidelines.

These findings must be considered within the context of study limitations. First, this sub‐study was only conducted in eight health facilities. Because we reached saturation within our sample and the results are consistent with findings from the larger impact evaluation, however, we believe that the facilities selected are representative of others in their districts [14, 15]. Second, the views of those who did not initiate treatment, did not return to care after tracing, or were not offered or did not choose an RPCS are not included, limiting our ability to determine how AGL implementation might be further adapted to access these individuals. Third, we did not stratify results by sex nor were we able to differentiate between responses from patients who were categorized as not stable because they were not virally suppressed and those categorized as not stable because they had missed visits. Finally, confusion amongst respondents with other policies and guidelines, the fact that existing ART guidelines already made provisions for fast track initiation, enhanced adherence counselling and tracing and the concurrent implementation of AGL interventions at some control sites made it difficult to isolate the specific AGL interventions in this analysis. This may explain the similar themes across intervention and control groups.

5. Conclusions

It is likely that some early implementation challenges will resolve with time and experience. Others, however, such as training, mentorship and site readiness will require more investment when taking the AGL to scale. Ensuring that providers are sufficiently trained and equipped to implement the interventions, that adherence and treatment strategies and policies are harmonized and aligned, and that patients are adequately informed about their treatment choices and understand the benefits of the AGL strategies will be critical elements for their continued implementation success at scale.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

NS, SP, MF and NFH conceptualized the study. NS and SP oversaw data analysis, prepared the draft manuscript and managed subsequent revisions. SP, JM and AH oversaw implementation of the study and all data collection and JM and RMF analysed the in‐depth interviews and focus group discussions, and contributed equally to writing the manuscript. AH, AM, SR, MF and NFH provided substantive feedback on several iterations of the manuscript. MP and YP oversaw implementation of the Adherence Guideline interventions and along with DW and MG provided feedback on the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. District profile for the four districts included in the evaluation of the South Africa’s National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the evaluation study team for their dedication and efforts interviewing and collecting these data and to all the patients, providers and implementers who participated in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the World Bank trust funds from several governments and Government of South Africa domestic health financing.

Pascoe, S. , Scott, N. A. , Fong, R. M. , Murphy, J. , Huber, A. N. , Moolla, A. , Phokojoe, M. , Gorgens, M. , Rosen, S. , Wilson, D. , Pillay, Y. , Fox, M. P. and Fraser‐Hurt, N. “Patients are not the same, so we cannot treat them the same” – A qualitative content analysis of provider, patient and implementer perspectives on differentiated service delivery models for HIV treatment in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020; 23(6):e25544

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

Trial registration number: NCT02536768.

References

- 1. UNAIDS . Country Factsheets South Africa 2017 [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2019 Apr 16] Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica

- 2. Fox MP, Rosen S. Retention of adult patients on antiretroviral therapy in low‐ and middle‐income countries: systematic review and meta‐analysis 2008–2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(1):98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fox MP, Shearer K, Maskew M, Meyer‐Rath G, Clouse K,Sanne I. Attrition through Multiple stages of pre‐treatment and ART HIV care in South Africa. Graham SM, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2014. Oct 20 [cited 2018 May 5];9:e110252 Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clouse K, Pettifor AE, Maskew M, Bassett J, Van Rie A, Behets F. Patient Retention from HIV diagnosis through one year on antiretroviral therapy at a primary health care clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet]. 2013. Feb 1 [cited 2018 May 5];62(2):e39–46. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23011400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Massyn N, Padarath A, Peer NDC.District health barometer 2016/17 [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2018 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.hst.org.za

- 6. World Bank . Analysis of Big Data for better targeting of ART Adherence Strategies: Spatial clustering analysis of viral load suppression by South African province, district, sub‐district and facility (April 2014‐March 2015) [Internet]. Washington DC; 2015. [cited 2018 Oct 18]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/25399 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Human Sciences Research Council . The fifth South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2017 [Internet]. Cape Town; 2018. [cited 2019 Apr 17]. Available from: http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/9234/SABSSMV_Impact_Assessment_Summary_ZA_ADS_cleared_PDFA4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosen S, Maskew M, Fox MP, Nyoni C, Mongwenyana C, Malete G, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy for HIV at a patient’s first clinic visit: the RapIT randomized controlled trial. PLoS Medicine. 2016;13:e1002015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grimsrud A, Barnabas RV, Ehrenkranz P, Ford N. Evidence for scale up: the differentiated care research agenda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20:22024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grimsrud A, Bygrave H, Doherty M, Ehrenkranz P, Ellman T, Ferris R, et al. Reimagining HIV service delivery: the role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2018 May 21];19(1):21484 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.7448/IAS.19.1.21484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) . 90–90‐90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland; 2014. [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90‐90‐90_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mavhu W, Willis N, Mufuka J, Bernays S, Tshuma M, Mangenah C, et al. Effect of a differentiated service delivery model on virological failure in adolescents with HIV in Zimbabwe (Zvandiri): a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet]. 2020. Feb 1 [cited 2020 Apr 16];8(2):e264–75. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31924539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Department of Health Republic of South Africa . Adherence guidelines for HIV, TB and NCDs [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: http://www.differentiatedcare.org/Portals/0/adam/Content/_YiT3_‐qmECUkmkpQvZAIA/File/SOPA5booklet20‐05‐2016.pdf

- 14. World Bank Group . Evaluation of the adherence guidelines for chronic diseases in South Africa: the impact of differentiated care models on final treatment and retention outcomes in HIV patients. Washington, DC: World Bank Group ; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fox MP, Pascoe SJS, Huber AN, Murphy J, Phokojoe M, Gorgens M, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for unstable patients on antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: results of a cluster randomized evaluation. Trop Med Int Heal [Internet]. 2018. Oct 3 [cited 2018 Oct 19]; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/tmi.13152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schneider H, Nxumalo N. Leadership and governance of community health worker programmes at scale: a cross case analysis of provincial implementation in South Africa. Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2017. Dec 15 [cited 2018 Apr 20];16(1):72 Available from: http://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939‐017‐0565‐3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Department of Health Republic of South Africa . Implementation of the universal test and treat strategy for HIV positive patients and differentiated care for stable patients [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2018 Sep 14]. Available from: https://sahivsoc.org/Files/22816CircularUTTDecongestionCCMTDirectorate(2).pdf

- 18. Grimsrud A, Sharp J, Kalombo C, Bekker L‐G, Myer L. Implementation of community‐based adherence clubs for stable antiretroviral therapy patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:19984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Massyn N, Peer N, English R, Padarath A, Barron P, Day C.District health barometer 2015/16 [Internet]. Durban; 2016. [cited 2018 May 5]. Available from: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/DistrictHealthBarometers/DistrictHealthBarometer2015_16.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fox MP, Pascoe SJ, Huber AN, Murphy J, Phokojoe M, Gorgens M, et al. Assessing the impact of the National Department of Health’s National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases in South Africa using routinely collected data: a cluster‐randomised evaluation. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lewin S, Glenton C, Oxman AD. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: methodological study. BMJ [Internet]. 2009. Sep 10 [cited 2018 May 5];339:b3496 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19744976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med [Internet]. 2014. Sep [cited 2019 May 20];89(9):1245–51. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00001888‐201409000‐00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chandler CI, DiLiberto D, Nayiga S, Taaka L, Nabirye C, Kayendeke M, et al. The PROCESS study: a protocol to evaluate the implementation, mechanisms of effect and context of an intervention to enhance public health centres in Tororo, Uganda. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2013. Dec 30 [cited 2018 May 5];8(1):113 Available from: http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748‐5908‐8‐113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Power R, Langhaug LF, Nyamurera T, Wilson D, Bassett MT, Cowan FM. Developing complex interventions for rigorous evaluation–a case study from rural Zimbabwe. Health Educ Res [Internet]. 2004. May 17 [cited 2018 May 5];19(5):570–5. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/her/article‐lookup/doi/10.1093/her/cyg073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Breimaier HE, Heckemann B, Halfens RJG, Lohrmann C. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): a useful theoretical framework for guiding and evaluating a guideline implementation process in a hospital‐based nursing practice. BMC Nurs [Internet]. 2015;14(1):43 Available from: http://bmcnurs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12912‐015‐0088‐4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Damschroder L. The role and selection of theoretical frameworks in implementation research [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/eis‐060712.pdf

- 28. Silverstein LB, Auerbach CF, Levant RF. Using qualitative research to strengthen clinical practice. Prof Psychol Res Pract [Internet]. 2006. [cited 2018 May 18];37(4):351–8. Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0735‐7028.37.4.351 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2019 Mar 21];27(4):591–608. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1049732316665344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci [Internet]. 2013. Sep [cited 2018 May 24];15(3):398–405. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization . Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland; 2015. [cited 2018 Sep 21]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186275/9789241509565_eng.pdf;jsessionid=39A084960418237D5023D8776A908AD1?sequence=1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ssonko C, Gonzalez L, Mesic A, Silveira Da Fonseca M, Achar J, Safar N, et al. Delivering HIV care in challenging operating environments: the MSF experience towards differentiated models of care for settings with multiple basic health care needs. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2018 Sep 21];20 Available from: 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bock P, Gunst C, Maschilla L, Holtman R, Grobbelaar N, Wademan D, et al. Retention in care and factors critical for effectively implementing antiretroviral adherence clubs in a rural district in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Bank Group . Evaluation of the National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases in South Africa: patient perspectives on differentiated care models [Internet]. Washington DC: World Bank, 2017. [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28874 [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Bank Group . Evaluation of the National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases in South Africa: healthcare provider perspectives on differentiated care models [Internet]. Washington DC: World Bank; 2017 [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28873 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mudavanhu M, West NS, Schwartz SR, Mutunga L, Keyser V, Bassett J, et al. Perceptions of community and clinic‐based adherence clubs for patients stable on antiretroviral treatment: a mixed methods study. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2020. Apr 1 [cited 2020 Apr 16];24(4):1197–206. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31560093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wilkinson L, Harley B, Sharp J, Solomon S, Jacobs S, Cragg C, et al. Expansion of the adherence club model for stable antiretroviral therapy patients in the Cape Metro, South Africa 2011–2015. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(6):743–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilkinson L, Grimsrud A, Cassidy T, Orrell C, Voget J, Hayes H, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial of extending ART refill intervals to six‐monthly for anti‐retroviral adherence clubs. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fox MP, Pascoe S, Huber AN, Murphy J, Phokojoe M, Gorgens M, et al. Adherence clubs and decentralized medication delivery to support patient retention and sustained viral suppression in care: Results from a cluster‐randomized evaluation of differentiated ART delivery models in South Africa. PLoS Medicine [Internet]. 2019. Jul 1 [cited 2020 Apr 16];16:e1002874 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31335865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Luque‐Fernandez MA, Van Cutsem G, Goemaere E, Hilderbrand K, Schomaker M, Mantangana N, et al. Effectiveness of patient adherence groups as a model of care for stable patients on antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grimsrud A, Lesosky M, Kalombo C, Bekker L‐G, Myer L. Implementation and operational research: community‐based adherence clubs for the management of stable antiretroviral therapy patients in Cape Town, South Africa: a cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(1):e16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Venables E, Edwards JK, Baert S, Etienne W, Khabala K, Bygrave H. “They just come, pick and go”. The acceptability of integrated medication adherence clubs for HIV and non communicable disease (NCD) patients in Kibera, Kenya. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mukumbang FC, Orth Z, van Wyk B. What do the implementation outcome variables tell us about the scaling‐up of the antiretroviral treatment adherence clubs in South Africa? A document review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sharp J, Wilkinson L, Cox V, Cragg C, van Cutsem G, Grimsrud A. Outcomes of patients enrolled in an antiretroviral adherence club with recent viral suppression after experiencing elevated viral loads. South Afr J HIV Med [Internet]. 2019. Jun 11 [cited 2020 Apr 16];20(1):905 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31308966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Venables E, Towriss C, Rini Z, Nxiba X, Cassidy T, Tutu S, et al. Patient experiences of ART adherence clubs in Khayelitsha and Gugulethu, Cape Town, South Africa: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0218340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Meyer‐Rath G, Johnson LF, Pillay Y, Blecher M, Brennan AT, Long L, et al. Changing the South African national antiretroviral therapy guidelines: the role of cost modelling. Lima VD, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017. Oct 30 [cited 2018 Jun 12];12:e0186557 Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pascoe SJS, Fox MP, Huber AN, Murphy J, Phokojoe M, Gorgens M, et al. Differentiated HIV care in South Africa: the effect of fast‐track treatment initiation counselling on ART initiation and viral suppression as partial results of an impact evaluation on the impact of a package of services to improve HIV treatment adherence. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2019. Nov 1 [cited 2020 Apr 16];22:e25409 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31691521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. National Department of Health Republic of South Africa . National Consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults [Internet]. Pretoria, South Africa; 2015. [cited 2018 Sep 21]. Available from: www.doh.gov.za [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fox MP, Maskew M, Brennan AT, Evans D, Onoya D, Malete G, et al. Cohort profile: the Right to Care Clinical HIV Cohort. South Africa. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. National Department of Health Republic of South Africa . Meeting Summary Report: Best Practices and Innovations in Linkage to Care, HIV Treatment, and Viral Suppression 31 [Internet]. Pretoria, South Africa; 2016. [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://za.usembassy.gov/our‐relationship/pepfar/partner‐dissemination‐meetings/reaching‐ [Google Scholar]

- 51. Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol [Internet]. 2008. Jun [cited 2018 Jul 11];41(3–4):327–50. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1007/s10464‐008‐9165‐0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. District profile for the four districts included in the evaluation of the South Africa’s National Adherence Guidelines for Chronic Diseases