As the world grapples with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, unforeseen sequela and public health implications continue to mount. Hospitals battle to keep patients alive while balancing worker safety amid rationing of personal protective equipment. Researchers race to discover a vaccine while politicians, communities, and neighborhoods debate shelter-in-place and social distancing regulations. Families experience financial devastation and loss of loved ones while parents and grandparents become full-time home care providers and educators. Throughout all the chaos, uncertainty, and increased sharing of home spaces are our children and domesticated pets who are also, albeit unexpected, victims of COVID-19 sequelae and stresses. Canine companions being particularly susceptible to these stresses, as they live amongst the ever-present angst of their caregivers, thus complicating their usual steadfast interactions.

Relationships with our companion dogs not only bring us joy, but science has also demonstrated that even brief positive interactions with dogs can decrease human stress and anxiety.1 For children living in a home with a dog, the benefits include increased responsibility and compassion, a sense of security and pride, and even positive impacts to the immune system. Potential risks of living with a dog, however, also exist—especially for the most vulnerable, younger, family members.

Dog bites cause significant harm to millions of people in the US each year.2 Children have the highest risk of dog bites, with large incidences and greater severity of injuries. Of the nearly 340 000 emergency department (ED) visits for dog bite injuries each year—equating to more than 900 per day—more than 40% of the victims are children and adolescents.3

Families with children and dogs are undergoing unique challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Caregivers have the additional tension of children staying at home 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for weeks and now months on end; little to no reprieve afforded by out-of-home activities such as school, playdates, parks, or libraries exist. Meanwhile, dogs in these households are presumably also experiencing untoward stress. Not only do the dogs have increased exposure to children, which may or may not be supervised, dogs may be experiencing “emotional contagion”—a state in which companion dogs mirror the emotions and stress levels of their human caregivers.4 Together, these unique circumstances can increase the likelihood of adverse interactions between children and their dogs.

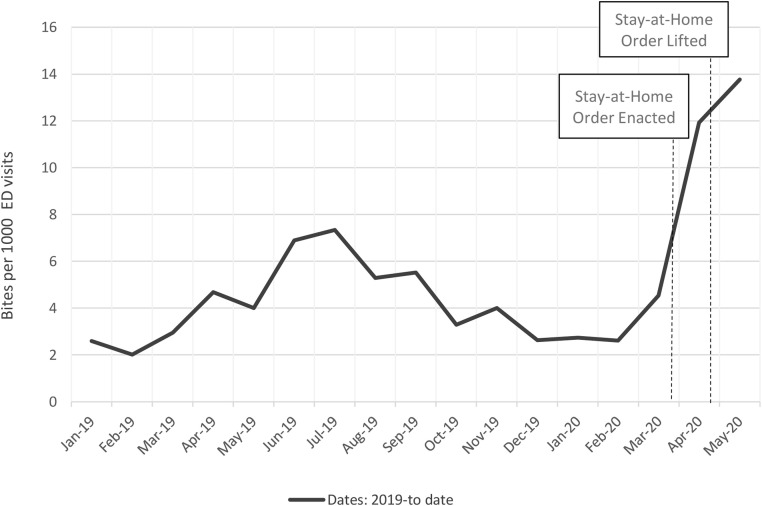

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and governmental directives to shelter-in-place, dog bite rates seem to be increasing. Our children's hospital has experienced an almost 3-fold increase in rates of visits to the pediatric ED because of dog bites since our statewide “stay-at-home” order was instituted (Figure ). High rates have persisted even amid recent relaxing of these regulations. To date, our institution's incidence of ED visits for dog bites is more than double that of summer rates, when these injuries are typically most common.

Figure.

Dog bite incidence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The reasons for the increased number of dog bites during the COVID-19 pandemic are multifactorial. Contributing factors may include increased child-dog exposure earlier in the year as a result of shelter-in-place regulations (ie, exposures similar to summer months when children are ordinarily out of school), greater dog stress given increased child presence and amplified household stress, and decreased adult supervision of children around dogs, due to new and competing home responsibilities for parents and caregivers.

We hypothesize that our experience of increased dog bite incidence is not unique. There are currently 82 million children5 and 77 million pet dogs6 living in the US—all experiencing some variation of shelter-in-place restriction. Thus, now more than ever, we urge healthcare providers, public health professionals, and injury control experts to strengthen and increase advocacy and educational efforts for prevention in order to minimize dog bites. We must remind families that children, especially those ages 5-9 years, have the highest incidence of dog bites. Infants and younger children have a higher likelihood of bites to the head and neck. Importantly, most dog bites occur by the family dog or another known dog. Dogs are more likely to bite in circumstances of resource guarding (such as in protecting their property, toys, and food) or if they are ill, excited, or frightened. Although evidence-based and expert-guided recommendations to prevent dog bites exist (Table ), the most important strategy to prevent dog bites is to always, always, supervise infants and children when they are near a dog.7 , 8

Table.

Strategies to prevent dog bites

| Always supervise an infant or child who is near a dog (even your own or another known dog). Any dog can bite! |

| Do not disturb any dog who is caring for puppies, eating, or sleeping. |

| Never reach through or over a fence to pet a dog. |

| Do not run past or from a dog. |

| Teach children to move slowly around dogs. |

| Do not encourage aggressive or rough play with any dog. |

| Always ask permission from a dog's owner before petting a dog. Always let the dog sniff your hand before petting a dog. |

| Never approach any unfamiliar dog. If an unfamiliar dog approaches, stand still with your arms to the side. |

| Keep your dog healthy and provide routine veterinary care. |

| Socialize and train your dog. |

It is our duty to provide frequent reminders to children, families, and dog owners now as we continue to coexist in this new norm. If we fall short, our nation will not only see the medical and other societal fall-out of COVID-19, but we may experience exponential increases of this preventable injury, affecting millions of children and their “historic best friend”—their dogs.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ein N., Li L., Vickers K. The effect of pet therapy on the physiological and subjective stress response: a meta-analysis. Stress Health. 2018;34:477–489. doi: 10.1002/smi.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilchrist J., Sacks J.J., White D., Kresnow M.J. Dog bites: still a problem? Inj Prev. 2008;14:296–301. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.016220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) WISQARS Cost of Injury Reports. https://wisqars.cdc.gov:8443/costT/cost_Part1_Finished.jsp Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 4.Sundman A.-S., Poucke E.V., Svensson Holm A.-C., Faresjö Å., Theodorsson E., Jensen P. Long-term stress levels are synchronized in dogs and their owners. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7391. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43851-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Census American Community Survey, 2017: ACS 1-year estimates data profiles. https://www.census.gov/data.html Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 6.American Veterinary Medical Association 2017-2018 U.S. pet ownership & demographics sourcebook. www.avma.org/resources-tools/reports-statistics/us-pet-ownership-statistics Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Dog bite prevention tips. www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/news-features-and-safety-tips/Pages/Dog-Bite-Prevention-Tips-2017.aspx Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Healthy pets, healthy people: how to stay healthy around dogs. www.cdc.gov/healthypets/pets/dogs.html