Abstract

A series of structurally diverse alcoholamine- and alkoxyalkylamine-functionalized variants of the metal–organic framework Mg2(dobpdc) are shown to adsorb CO2 selectively via cooperative chain-forming mechanisms. Solid-state NMR spectra and optimized structures obtained from van der Waals-corrected density functional theory calculations indicate that the adsorption profiles can be attributed to the formation of carbamic acid or ammonium carbamate chains that are stabilized by hydrogen bonding interactions within the framework pores. These findings significantly expand the scope of chemical functionalities that can be utilized to design cooperative CO2 adsorbents, providing further means of optimizing these powerful materials for energy-efficient CO2 separations.

Keywords: Carbon Capture, Density Functional Theory Calculations, Inorganic Chemistry Materials Science: General, Metal-Organic Frameworks, NMR Spectroscopy

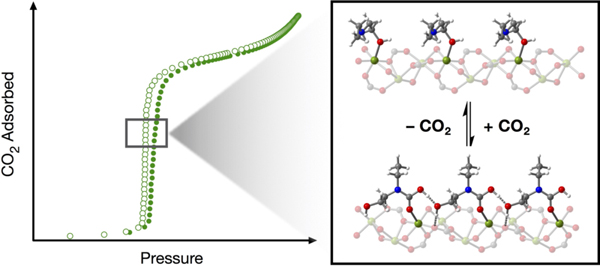

Graphical abstract

Cooperative CO2 chemisorption is achieved in a metal–organic framework functionalized with structurally-diverse alcoholamines and alkoxyalkylamines. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy and density functional theory calculations indicate that CO2 adsorption occurs via the formation and propagation of hydrogen bond-stabilized carbamic acid or ammonium carbamate structures.

Introduction

Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are rising rapidly, recently exceeding an unprecedented global average of 410 ppm,[1] and will likely have an irreversible impact on climate worldwide.[2,3] Fossil fuel combustion accounts for the largest percentage of anthropogenic CO2 emissions to date.[2] Therefore, it is of paramount importance to develop cost-effective strategies for mitigating CO2 emissions from traditional energy sources. Carbon capture and sequestration (CCS)[4,5] is one leading strategy proposed to reduce CO2 emissions from point sources, but its implementation using current technologies would result in an estimated >30% increase in the levelized cost of electricity.[3,4] Given that CO2 separation alone accounts for ~70–80% of the total cost associated with CCS,[4] the development of new CO2-selective materials could dramatically increase the viability of this approach.

Diamine-appended variants of the metal–organic framework Mg2(dobpdc) (dobpdc4− = 4,4’-dioxidobiphenyl-3,3’-dicarboxylate) have been shown to adsorb large quantities of CO2 through a unique cooperative adsorption mechanism, involving the insertion of CO2 into metal–amine bonds to form ammonium carbamate chains (Figure 1).[6] This mechanism is characterized by step-shaped CO2 adsorption profiles, which contribute to high material working capacities and low regeneration energies. Additionally, the pressure and temperature at which the adsorption step occurs can be tuned simply by changing the diamine, making these materials promising candidates for a range of carbon capture applications.[6–13] Ammonium carbamate chain formation remains the only cooperative CO2 chemisorption mechanism known to date, and the development of new cooperative adsorption mechanisms would greatly expand the scope of these energy-efficient carbon capture materials.

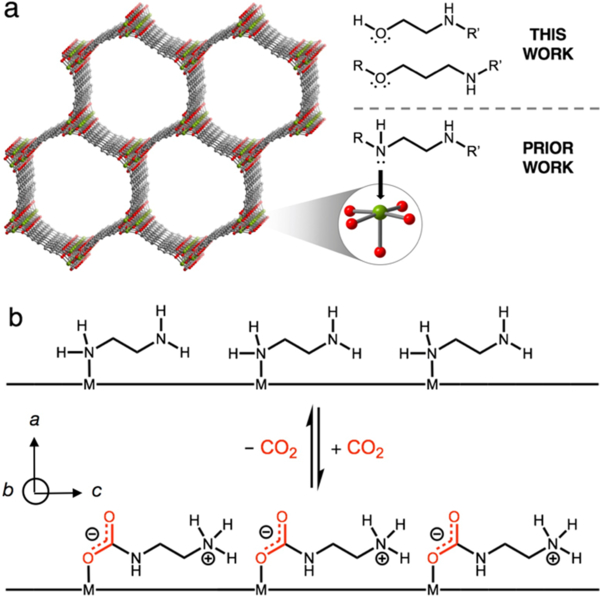

Figure 1.

(a) Structure of the metal−organic framework Mg2(dobpdc). Grey, red, and green spheres represent C, O, and Mg atoms, respectively; hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. The diamine-appended material exhibits cooperative CO2 adsorption arising from (b) insertion of CO2 into the Mg–amine bond followed by proton transfer to form an ammonium carbamate, a process that propagates down the c-axis of the material. In this work, we expand this family of materials by demonstrating cooperative CO2 adsorption in alcohol- and alkoxyalkylamine-appended variants of Mg2(dobpdc).

We have recently shown that changing the structure of the appended diamine can lead to new adsorption mechanisms, including the formation of carbamic acids.[14,15] Based on this finding, we envisioned that more significant structural variations in this system, such as replacement of the appended diamines with other bifunctional molecules (Figure 1), could lead to new mechanisms for cooperative adsorption. Herein, we demonstrate via gas adsorption, spectroscopic, and computational studies that alcoholamine- and alkoxyalkylamine-appended variants of Mg2(dobpdc) indeed undergo cooperative CO2 adsorption through related but distinct mechanisms.

Results and Discussion

Alcoholamines are often significantly less expensive than the corresponding diamines and are thus attractive for the design of scalable adsorbents for carbon capture. Indeed, current large-scale carbon capture applications are primarily carried out with aqueous alcoholamine solutions, due both to their low cost and scalability.[8] However, cooperative adsorption of CO2 in diamine-appended metal–organic frameworks occurs when one amine reacts with CO2 to form a metal-bound carbamate and the other accepts a proton from this site to form a charge-balancing ammonium species, a reaction that propagates down the pore channels (Figure 1b).[6] Given that alcoholamines cannot react by this mechanism,[16] it was unclear prior to this work if alcoholamine-appended frameworks could undergo cooperative adsorption via a related mechanism.

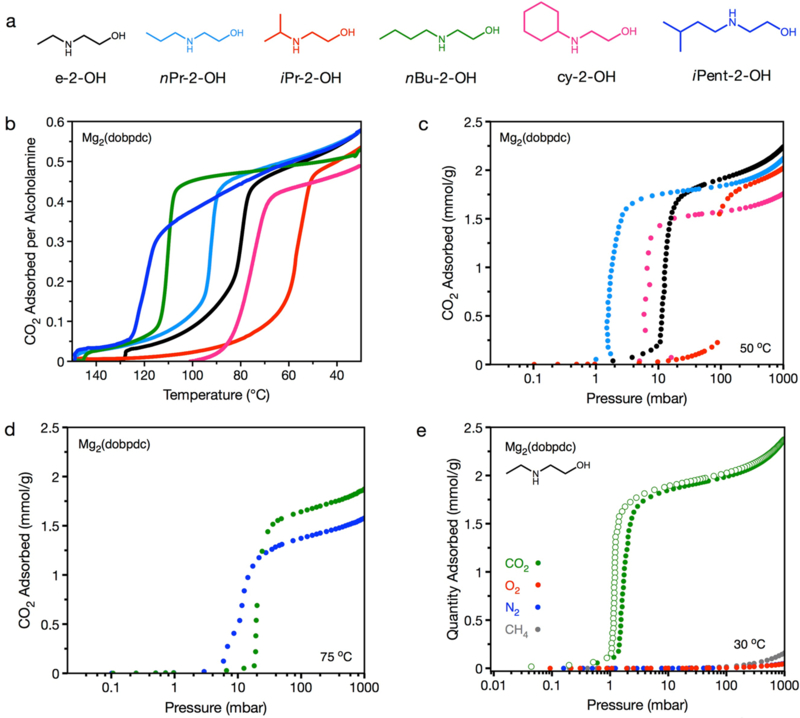

We prepared a diverse range of alcoholamine-appended variants of Mg2(dobpdc), using our previously reported procedure for diamines.[6] The resulting materials were isolated as highly crystalline powders, as confirmed by powder X-ray diffraction analysis (Figures S6–12). Isobaric and isothermal (Figure 2) measurements revealed reversible (Figures S83–84) step-shaped adsorption behavior for materials bearing alcoholamines with moderately bulky secondary amine groups, including ethyl (e-2-OH), n-propyl (nPr-2-OH), isopropyl (iPr-2-OH), n-butyl (nBu-2-OH), cyclohexyl (cy-2-OH), and isopentyl (iPent-2-OH). Other alcoholamines, such as 3-aminopropanol (3-OH), also gave rise to modest cooperative adsorption profiles (Figure S40). Alcoholamine-appended variants of Mg2(dobpdc) with very sterically hindering amine substituents (e.g., t-butyl), as well as those with tertiary amines, did not appreciably adsorb CO2, suggesting that reaction at the amine sites may be essential for achieving step-shaped adsorption (Figures S44 and S46). As observed previously for diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) materials,[7] we found that substituent size affects the step temperatures and pressures. However, in contrast to the diamine-appended frameworks, for which larger alkyl groups led to low adsorption step temperatures, longer amine alkyl chains generally led to an increase in the adsorption threshold temperature or a decrease in the adsorption threshold pressure for alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc). The CO2 adsorption step temperatures range from 60 °C for iPr-2-OH to 125 °C for iPent-2-OH (Figure 2b). Isothermal measurements reflected the same trend, with the adsorption step pressures at 50 °C ranging from ≤5 mbar for nPr-2-OH to 100 mbar for iPr-2-OH (Figure 2c). The adsorption step pressures for nBu-2-OH and iPent-2-OH were found to be ≤1 mbar at 50 °C, reflecting the strong adsorption of CO2 in these materials, and thus data were measured at 75 °C instead (Figure 2d). Importantly, minimal adsorption of O2, N2, and CH4 was observed in e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) at 30 °C (Figure 2e), further indicating that this family of materials could be promising for the selective removal of CO2 from flue gas streams.

Figure 2.

(a) Structures of e-2-OH–, nPr-2-OH–, iPr-2-OH–, nBu-2-OH–, cy-2-OH–, and iPent-2-OH alcoholamines appended to Mg2(dobpdc). Colors correspond to data presented in plots in (b)–(d) for the respective alcoholamine-appended frameworks. (b) Pure CO2 adsorption isobars obtained at 1 bar for e-2-OH–, nPr-2-OH–, iPr-2-OH–, nBu-2-OH–, cy-2-OH–, and iPent-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), as measured by thermogravimetric analysis. Each framework exhibits a maximum capacity of 1 CO2 molecule per two alcoholamines (0.5 CO2 per amine). (c) CO2 adsorption isotherms obtained at 50 °C for e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), nPr-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), iPr-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), and cy-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). (d) CO2 adsorption isotherms obtained at 75 °C for nBu-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) and iPent-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). All isotherm samples were activated under flowing N2 at the previously described temperatures (Table S2) for 0.5 h, followed by activation under high vacuum (<10 μbar) at 110 °C for 4 h. (e) Single-component gas adsorption isotherms for e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) at 30 °C. Closed and open circles represent adsorption and desorption data, respectively. A capacity of 2 mmol/g corresponds to 1 CO2 adsorbed per 2 molecules of e-2-OH.

Notably, only the Mg2+ congeners of alcoholamine-appended M2(dobpdc) frameworks exhibit step-shaped CO2 adsorption profiles, while variants with M2+ = Mn, Co, Ni, and Zn lack adsorption steps (SI Section 8). We hypothesize this result is primarily due to the stronger thermodynamic driving force for CO2 adsorption in the Mg2+ frameworks, consistent with our prior result for diamine-appended materials where the step pressure increased with metal(II) identity in the order Mg < Mn < Fe < Zn < Co.[6] In the absence of single crystals of alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc), we turned to powder X-ray diffraction characterization to elucidate the structure of these materials upon CO2 adsorption. While it was possible to obtain unit cell parameters for activated and CO2-dosed e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) and nPr-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) (Tables S6–S7), a large amount of disorder for both frameworks precluded structure solutions. Even still, the unique adsorption behavior of alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) within the M2(dobpdc) family suggests that the breaking of a metal–ligand bond is necessary to initiate chemisorption.

For the alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) variants that exhibit step-shaped adsorption, the post-step adsorption capacity corresponds to one CO2 molecule per two alcoholamines. While this capacity is half the total observed for diamine-appended variants, it is consistent with a ratio of one CO2 molecule adsorbed for every two amines.[6] We previously reported that 1°,2°-alkylethylenediamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) variants exhibit two distinct adsorption steps, each with a capacity of one CO2 molecule per two diamines.[17] In these materials, CO2 initially adsorbs only at half of the metal sites due to unfavorable steric interactions in the a-b plane, and saturation occurs upon increasing the thermodynamic driving force for adsorption, via an increase in the CO2 pressure or decrease in the temperature. We considered that similar steric restrictions might be leading to the observed capacity for alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc), but neither higher pressure isothermal measurements (Figure S80) nor lower temperature isobaric measurements (Figure S63) revealed a second adsorption step for e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). Interestingly, no stepped adsorption was found for alcoholamine-appended variants of Mg2(pc-dobpdc) (pc-dobpdc4− = 3,3’-dihydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4,4’-dicarboxylic acid) or Mg2(dotpdc) (dotpdc4− = 4,4-dioxido-[1,1’:4’,1”-terphenyl]-3,3”-dicarboxylate), which feature larger metal site separations in the a-b plane relative to Mg2(dobpdc) (Figures S42–43).[17] Powder X-ray diffraction studies of both e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) and nPr-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) further revealed a pronounced contraction in both the a and b unit cell parameters upon CO2 adsorption (−1.5% and −1.9% for nPr-2-OH and e-2-OH, respectively; Table S8), indicative of favorable interactions in the a-b plane that are generally not evident for diamine-appended frameworks. Overall, these findings suggest that, distinct from diamine-appended frameworks, alcoholamine-appended frameworks exhibit stabilizing hydrogen bonding interactions in the a-b plane that involve two alcoholamines per molecule of adsorbed CO2. Consistently, while the differential enthalpy of CO2 adsorption in e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) was found to be comparable to that for the N-ethylethylenediamine-appended framework (−81(4) vs. −84(3) kJ/mol, respectively),[7] the entropic penalty is larger (−214(11) vs. −186(14) J/mol·K, respectively) (Figure S77), reflecting the increased ordering upon CO2 adsorption in this system.

Given the evidence of stabilizing hydrogen bonding interactions upon CO2 adsorption in alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc), we examined how adsorption under humid conditions might alter or disrupt these interactions. Interestingly, adsorption isobars obtained under humid conditions (Figure S68) revealed that CO2 uptake remains largely unchanged for nBu-2-OH and iPent-2-OH materials, although a clear tail can be seen at 40 °C, indicative of further adsorption of water and/or CO2. For e-2-OH, nPr-2-OH, iPr-2-OH, nBu-2-OH, and cy-2-OH, the humid adsorption curves exhibit substantial changes from the dry adsorption data, although they all still feature a single adsorption step that notably appears at higher temperatures than under dry conditions. For the latter set of materials, the humid adsorption data also exhibit a similar low-temperature tail suggestive of a second adsorption step (Figure S68). The uptake behavior of these materials in the presence of water is clearly complex and is an ongoing area of investigation in our laboratory. Here, we note that the increase in adsorption step temperature for some of these frameworks suggests that water may enhance critical hydrogen bonding interactions that occur between adsorbed CO2 and the alcoholamines. However, given that the CO2 adsorption capacity for some frameworks is diminished in the presence of water, such stabilization is not a general characteristic of all alcoholamine-appended frameworks in the presence of water.

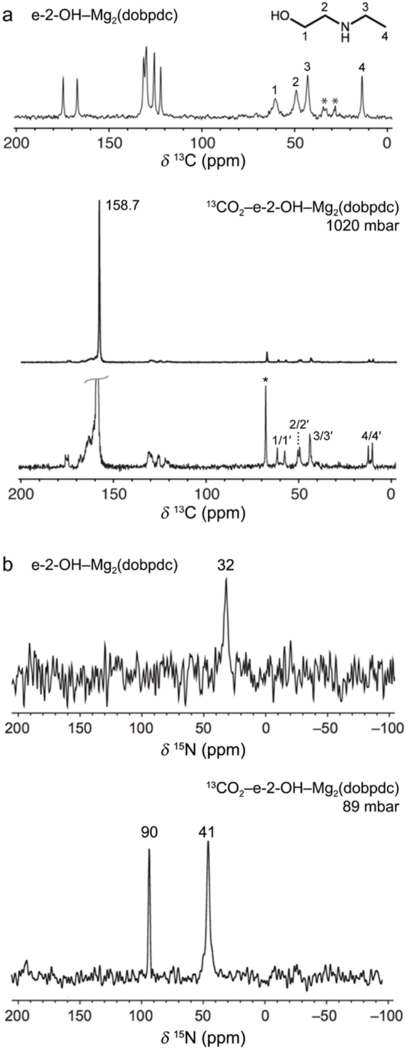

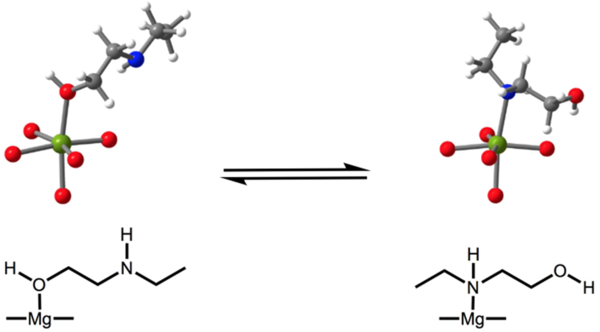

We turned to solid-state magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy to elucidate the structure and local environment of the alcoholamine-appended frameworks upon adsorption of isotopically enriched 13CO2 (Figure 3).[18] The 13C NMR spectrum of activated e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) features broad, low-intensity resonances (Figure 3a) and the 15N NMR spectrum of activated e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) also reveals a single broad peak at 32 ppm (Figure 3b). Together, these spectra are consistent with DFT predictions of dynamic O/N binding to the metal center in this material in the absence of CO2 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

(a) Carbon-13 solid-state NMR spectra for activated (MAS rate = 17 kHz) and 13CO2-dosed (MAS rate = 16 kHz) e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). Asterisks mark spinning side bands. Peaks within the 120–180 region in the activated spectrum correspond to the dobpdc4− ligand carbon atoms. Small secondary 13CO2 resonances ranging from 160–170 ppm may be due to minor side products arising from noncooperative chemisorption. (b) Nitrogen-15 solid-state NMR spectra for activated and 13CO2-dosed e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) (MAS rate = 15 kHz).

Figure 4.

DFT structures of e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) featuring oxygen- and nitrogen-bound e-2-OH. The N-bound structure is more favorable than the O-bound structure by only 1.5 kJ/mol (within computational error), suggesting that the binding mode is dynamic. These calculations were repeated for all alcoholamines and it was found that, apart from e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), all activated materials feature alcoholamines preferentially bound through oxygen, due to steric bulk of the amine substituent. Grey, red, white, blue, and green spheres represent C, O, H, N, and Mg atoms, respectively.

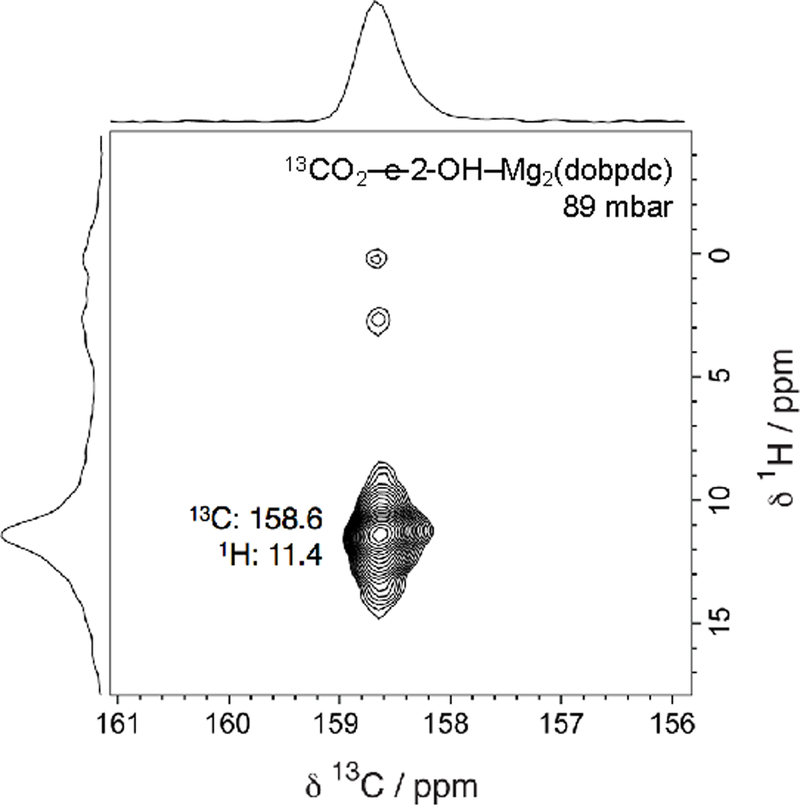

Upon dosing the sample with 13CO2, we observed a dominant resonance at 158.7 ppm in the 13C spectrum (Figure 3a). This chemical shift is less than those observed for ammonium carbamates formed in diamine-appended frameworks[6,14,15,19,20] and is within range of previously reported shifts for the carbonyl carbons of carbamic acids and ammonium alkylcarbonates.[15,19–22] Small, secondary 13CO2 resonances ranging from 120–180 ppm are due to the dobpdc4− ligand, whereas small resonances within 160–170 ppm may be due to minor side products arising from noncooperative chemisorption (Figure 3a). Splitting of the alcoholamine alkyl 13C resonances is also apparent, consistent with the adsorption of CO2 at only half of the alcoholamine sites. The 15N NMR spectrum of 13CO2-dosed e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) features two distinct resonances at approximately 41 and 90 ppm (Figure 3b). The latter value is slightly higher than 15N chemical shifts reported for 13CO2-dosed diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) (73.3–86.5 ppm) and is assigned to an amine that has reacted with CO2.[15] Importantly, this resonance strongly suggests that CO2 reacts at nitrogen rather than at oxygen. The resonance at ~41 ppm is slightly higher than the chemical shift for the activated alcoholamine-appended framework (32 ppm) and likely corresponds to a free alcohol from a bound alcoholamine participating in hydrogen bonding. The similar intensities of the two resonances in the 13CO2-dosed 15N spectrum further indicate that the two alcoholamine environments are present in equal proportion. These experiments were repeated for iPr-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) and very similar results were obtained (Figures S70–72), suggesting that other alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) variants adsorb CO2 via a similar mechanism. Lastly, 13C–1H NMR correlation measurements indicate the presence of carbamic acid or ammonium protons (11.4 ppm) strongly interacting with the carbonyl carbon of the 13CO2-adsorbed product (Figure 5). This 1H chemical shift value is similar to those previously measured for carbamic acids and is lower than those measured for ammonium carbamates featuring secondary ammonium ions,[15] suggesting that carbamic acid is formed upon CO2 adsorption in this material. Overall, these NMR data are consistent with the formation of hydrogen bond-stabilized carbamic acids upon CO2 adsorption in alcoholamine-appended frameworks.

Figure 5.

13C–1H HETCOR (contact time 100 μs) NMR spectrum for CO2-dosed e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). A single dominant correlation is observed at a 1H shift of 11.4 ppm and a 13C shift of 158.6 ppm, assigned to a carbamic acid –COOH group. Small correlations are observed at lower 1H chemical shifts regions that likely correspond to alcoholamine protons.

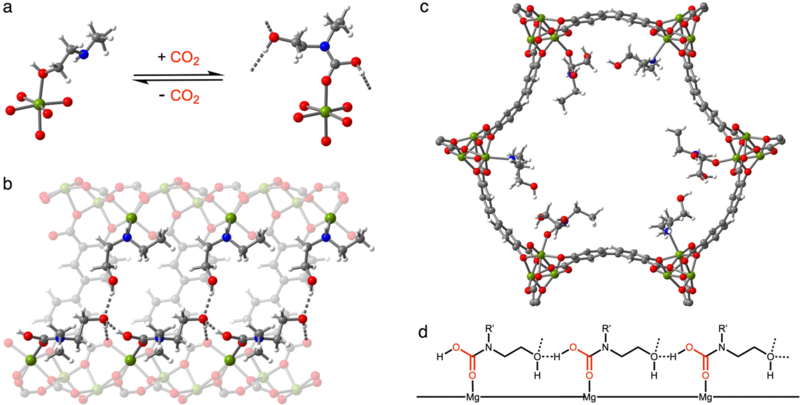

Using van der Waals (vdW)-corrected density functional theory (DFT), we investigated five possible mechanisms (A–E, Table 1 and Figures 6–7) for cooperative CO2 adsorption in e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). This material was chosen as it features the smallest alcoholamine to participate in cooperative adsorption and thus offers the simplest case for computational modeling. Previous experimental[6,7,14,15,17,19] and computational[10,21,23] studies of CO2 adsorption in diamine-appended metal–organic frameworks served as a valuable basis for these calculations, as they provided initial structures for calculations as well as documented experimental observations validating different mechanisms. The best agreement between theory and experiment was observed for mechanism A (Table 1), which involves the unprecedented formation of hydrogen bond-stabilized carbamic acid chains along the pores of the framework (Table 1 and Figure 6). Although this mechanism is similar to the ammonium carbamate chain formation observed experimentally in many diamine-appended frameworks,[6,7] it occurs without proton transfer to a neighboring amine. Hydrogen bond donation occurs from the carbamic acid to the neighboring terminal alcohol along the c-axis, and this alcohol donates a hydrogen bond to the non-bridging carboxylate oxygen atom of the ligand. The carbamic acid structure is further stabilized via O–H hydrogen bond donation from the neighboring alcoholamines in the a-b plane of the framework. The extensive hydrogen bonding accounts for the energetic stability of this structure, despite the documented instability of carbamic acids.[24–27] In addition, this mechanism is consistent with the experimentally observed capacity of one CO2 per two alcoholamines and the a-b unit cell contraction observed by powder X-ray diffraction (Table S8). The formation of extended hydrogen-bonding chains along the c-axis of the structure accounts for the experimentally observed step-shaped adsorption profiles and importantly confirms that ion-pairing interactions are not a prerequisite for the cooperative chemisorption of CO2.

Table 1.

Comparison of experimental data with DFT results for calculated CO2 adsorption mechanisms in e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). Mechanism A yields the most stable CO2-inserted structure and the best correlation with experimental data. Chemical shift values are reported in ppm. For the 15N shifts, the first value corresponds to CO2-inserted amine nitrogen and the second value to free amine nitrogen.

| Experiment | Mechanism A | Mechanism B | Mechanism C | Mechanism D | Mechanism E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E (eV) | - | −1050.919 | −1050.545 | −1050.234 | −1105.249 | −1049.916 |

| EB (kJ/mol) | −81(4) | −78 | −66 | −57 | −57 | −47 |

| a (Å) | 21.255(1) | 21.299 | 21.856 | 21.818 | 19.618 | 20.828 |

| c (Å) | 6.875(4) | 7.053 | 7.077 | 7.034 | 6.851 | 7.095 |

| δ 15N | 90(2), 41(2) | 102.4, 38.7 | 101.4, 40.4 | 101.7, 35.9 | 46.2, 33.0 | 118.2, 56.3 |

| δ 13C (C=O) | 158.5(1) | 158.5 | 158.6 | 161.7 | 158.5 | 153.7 |

Figure 6.

(a) DFT-predicted crystal structures of e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) with oxygen-bound e-2-OH (left) and CO2-inserted e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) (right). (b) Predicted structure of CO2-inserted e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), as viewed along the pore wall. (c) View down the c-axis of the predicted structure of CO2-inserted e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc). All structures were calculated as described in Section 17 of the Supporting Information. Grey, red, blue, white, and green spheres represent C, O, N, H, and Mg atoms, respectively. (d) Proposed CO2 adsorption mechanism for alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) involving hydrogen bond-stabilized carbamic acid chains.

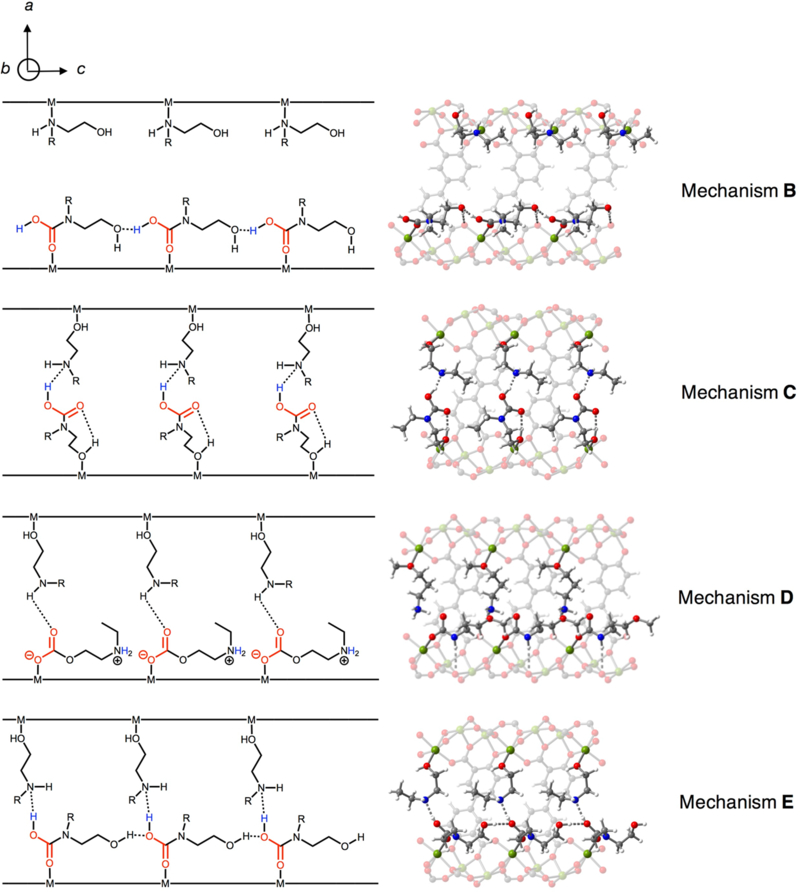

Figure 7.

Additional mechanisms considered for CO2 adsorption in e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), as viewed along the c-axis (according to Figure 1 reference axes). Grey, red, blue, white, and green spheres represent C, O, N, H, and Mg atoms, respectively. Mechanism B features a single carbamic acid chain and free alcoholamine across the a-b plane without stabilizing hydrogen bonding interactions as present in mechanism A. Mechanism C features dangling carbamic acids stabilized by the free amines across the pore that are capable of hydrogen bonding interactions. In this mechanism, no interactions are present along the c-axis of the framework. Mechanism D features a single ammonium alkylcarbonate chain with hydrogen bonding stabilization in the a-b plane by an adjacent amine. Mechanism E features a carbamic acid chain with stabilization in the a-b plane, but with the uninserted alcoholamine in the “opposite” configuration to that in mechanism A.

The other calculated mechanisms in Table 1 and Figure 7 provide critical insight into the unique viability of mechanism A. Similar to mechanism A, mechanism B features a single carbamic acid chain with stabilizing hydrogen bonding interactions between neighboring alcohol groups along the c-axis. While the structure is relatively stable, the mechanism features no interaction between the carbamic acid chain and the neighboring alcoholamine in the a-b plane and thus does not account for the unit cell contraction observed via powder X-ray diffraction. Mechanism C involves the interaction of a “dangling” carbamic acid formed from one alcoholamine with a neighboring alcoholamine in the a-b plane of the framework, similar to a carbamic acid pair mechanism studied previously for amine-appended frameworks.[14,28,29] The binding energy predicted for this mechanism (−57 kJ/mol) is smaller than the experimental value, and this pairing mechanism alone would likely not be inherently cooperative.[28] Therefore, an adsorption step arising from this mechanism would likely be due to a unit cell change upon CO2 adsorption. However, the −1.5% unit cell contraction in e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) is unlikely to be dramatic enough to propagate a lattice distortion and lead to an adsorption step. [30] Furthermore, it is difficult rationalize how mechanism C would account for exclusive adsorption in alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) and not the other alcoholamine-appended M2(dobpdc) frameworks. For these reasons, we consider mechanism C unlikely. We also considered that reaction at oxygen could lead to ammonium alkylcarbonate chain (mechanism D), but this mechanism was less thermodynamically favored than mechanism A and is inconsistent with our 15N NMR data. Finally, we considered mechanism E, which features the free stabilizing alcoholamine in an opposite configuration to that in A, wherein the alcohol is bound to the metal and the amine serves as the hydrogen bond acceptor/donor. This structure is associated with a low CO2 binding enthalpy of −47 kJ/mol and the predicted NMR shifts are the least consistent with our data, excluding this mechanism as a possibility. Ultimately, mechanism A affords the best agreement with our experimental data.

The predicted structure for CO2 adsorbed in e-2-OH via mechanism A suggests that the primary role of the alcohol in alcoholamine-appended frameworks is as a hydrogen-bond acceptor (Figure 6). Based on this rationale, we considered that alkoxyalkylamine-appended frameworks, featuring an –OR group, should therefore also be capable of cooperative CO2 adsorption. Indeed, isobaric and isothermal CO2 adsorption measurements revealed that primary alkoxyalkylamine-functionalized Mg2(dobpdc) variants also exhibit step-shaped adsorption profiles (Figure 8a). For example, variants of Mg2(dobpdc) appended with 3-methoxypropylamine (3-O-m) and 3-ethoxypropylamine (3-O-e) display step-shaped adsorption/desorption profiles (Figure 8 and S47) with adsorption capacities corresponding to one CO2 per two alkoxyalkylamines. In contrast, alkoxyalkylamine-appended M2(dobpdc) (M = Mn, Co, Ni, Zn) exhibit little to no cooperative adsorption, as observed with the alcoholamine-appended frameworks (SI Section 8). Critically, Mg2(dobpdc) functionalized with the monoamine n-butylamine exhibited no CO2 adsorption (Figure 8b), indicating that both an amine and another Lewis basic functional group are necessary to achieve cooperative CO2 insertion.

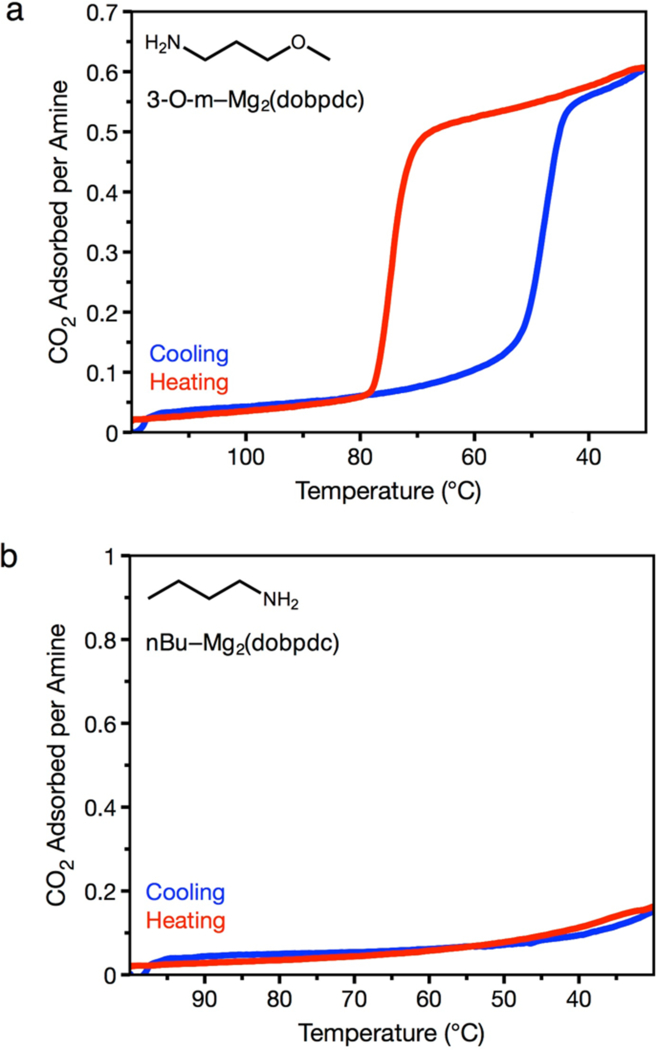

Figure 8.

a) Pure CO2 adsorption (blue) and desorption (red) isobars at 1 bar for 3-O-m–Mg2(dobpdc) (3-O-m = 3-methoxypropylamine), as measured by thermogravimetric analysis. b) Pure CO2 adsorption (blue) and desorption (red) isobars at 1 bar for n-butyl–Mg2(dobpdc), as measured by thermogravimetric analysis.

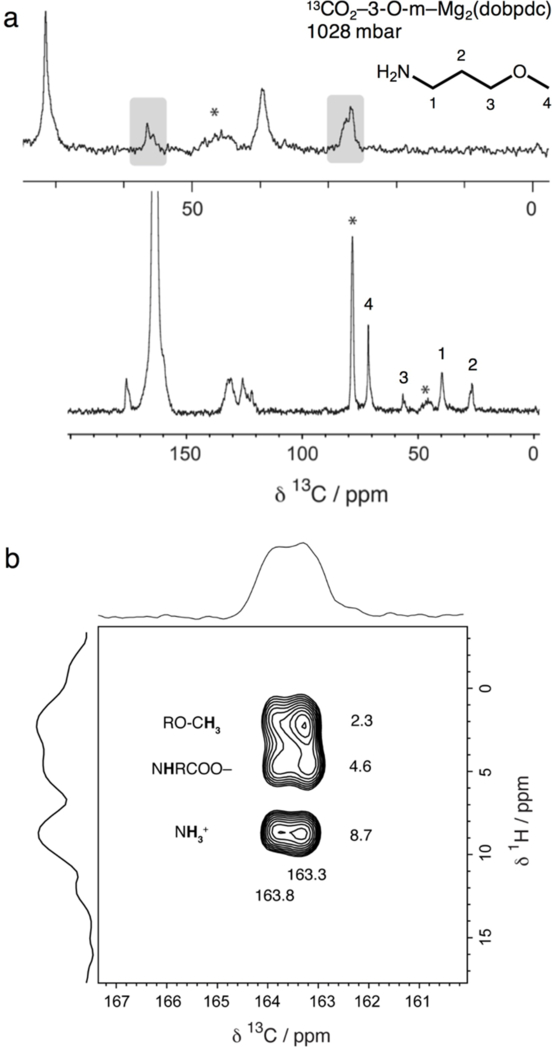

Solid-state magic angle spinning 13C NMR spectroscopy was used to characterize activated and CO2-dosed 3-O-m–Mg2(dobpdc) and compare the mechanism of CO2 adsorption with that observed for the alcoholamine-appended materials (Figure 9a). Dosing with 13CO2 resulted in splitting of the alkyl peaks, similar to what occurs for the alcoholamines (Figure 3a). In addition, a broad yet distinct carbonyl resonance at 163.6 ppm was assigned to inserted 13CO2. This shift is higher than that observed for 13CO2 inserted in e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) (Figure 3a) and is more consistent with an ammonium carbamate than with a carbamic acid. Furthermore, the 13C–1H HETCOR spectrum (Figure 9b) revealed distinct correlations between the 13C of the carbonyl group and 1H resonances at 4.6 and 8.7 ppm, corresponding to an amine N–H and an ammonium N–H, respectively. A correlation was also observed at 2.3 ppm, which likely corresponds to the methyl ether. It is unlikely that this value corresponds to N–H correlation, due to its low chemical shift value. As the 13C and 1H NMR chemical shifts are within range of documented resonances for ammonium carbamate formation in diamine-appended frameworks,[15] these spectra suggest that ammonium carbamate formation occurs in this material, in contrast to the carbamic acid formation observed for alcoholamines.

Figure 9.

(a) 13C cross polarization (contact time 1 ms) NMR spectrum of 13CO2-dosed 3-O-m–Mg2(dobpdc). The split alkyl resonances are roughly equivalent (grey boxes). The carbonyl carbon chemical shift (163.6 ppm) is larger than that of e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc), likely due to formation of an ammonium carbamate species. Asterisks mark spinning sidebands. Minor peaks within the 120–180 ppm region correspond to the dobpdc4− linker. (b) 13C–1H HETCOR (contact time 100 μs) NMR spectrum for 13CO2-dosed 3-O-m–Mg2(dobpdc). Three dominant correlations are observed at 1H shifts of 2.3, 4.6, and 8.7 ppm (assigned to the methyl ether protons, inserted amine proton, and ammonium group of an ammonium carbamate, respectively) and 13C shifts of 163.3 and 163.8 ppm. The two sets of correlations observed in the 13C dimension suggest the presence of two subtly different local carbonyl environments.

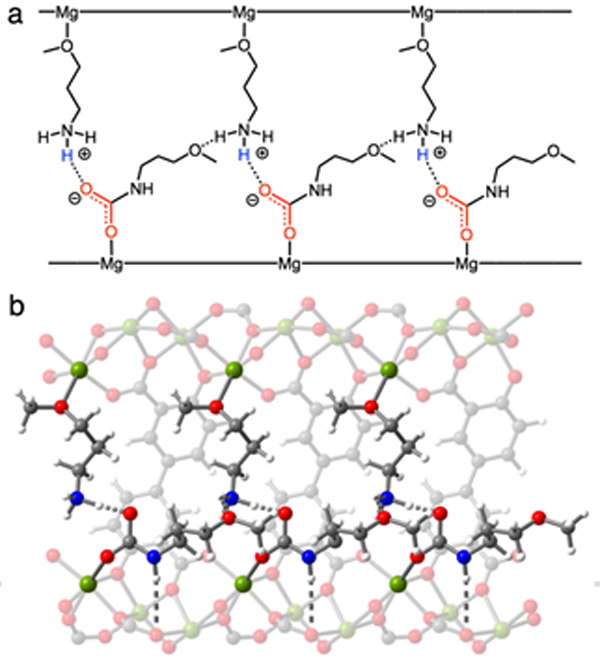

We again utilized vdW-corrected DFT calculations to evaluate a candidate structure for the CO2-inserted phase of 3-O-m–Mg2(dobpdc), using the CO2-inserted structure of e-2-OH–Mg2(dobpdc) as a starting point. Similar to alcoholamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) variants, a variation of mechanism A (Aʹ, Figure 10) best accounts for our experimental observations. Mechanism Aʹ features an ammonium carbamate that donates a hydrogen bond to the neighboring free methoxy group across the a-b plane. Here, the stabilizing, non-inserted alkoxyalkylamine was found to bind in opposite configuration to the non-inserted alcoholamine in mechanism A. Although we investigated the formation of the carbamic acid tautomer, we found this configuration to be less stable than complete proton transfer to the neighboring amine to form an ammonium carbamate. Overall, this predicted structure suggests that the preferred tautomer (carbamic acid or ammonium carbamate) depends on the appended bifunctional molecule, with alcoholamines favoring carbamic acids and alkoxyalkylamines favoring ammonium carbamates. However, while the exact nature of the hydrogen-bonding motif is dependent on the structure of the appended alcoholamine or alkoxyalkylamine, the formation of chains featuring metal-bound CO2 is conserved among this new family of cooperative adsorbents.

Figure 10.

(a) Structural model of CO2-inserted 3-O-m–Mg2(dobpdc), as viewed along the c-axis. (b) Predicted structure of CO2-inserted 3-O-m–Mg2(dobpdc), as viewed along the c-axis. All structures were calculated with DFT (see SI Section 17). Grey, red, blue, white, and green spheres represent C, O, N, H, and Mg atoms, respectively.

Conclusion

We have characterized two new cooperative mechanisms for CO2 adsorption in alcoholamine- and alkoxyalkylamine-functionalized variants of the metal–organic framework Mg2(dobpdc). Importantly, these materials represent new members of a growing family of framework materials capable of cooperative CO2 chemisorption, which previously included only diamine-appended frameworks.[31,32] Taken together, computational and structural studies, solid-state NMR spectra, and gas adsorption data indicate that the key to achieving cooperative CO2 adsorption in all of these materials is the formation of chain-like structures along the c-axis of the framework, via ion-pairing in diamine-appended frameworks and via hydrogen-bonding in the materials presented here. This discovery greatly increases the scope of functionalized materials that can undergo cooperative CO2 adsorption and paves the way for the realization of a host of new cooperative adsorbents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Synthesis and gas adsorption measurements were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) under the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) grant FWP-00006194. Crystallographic, solid-state NMR, and computational studies were supported by the U.S. DoE, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award DE-SC0019992. Computational work was additionally supported by the Molecular Foundry through the U.S. DoE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We acknowledge the use of computational resources at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). This work also utilized the resources of the Advanced Photon Source, DoE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DoE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. We thank the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health for a postdoctoral fellowship for P.J.M. (F32GM120799). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank the Philomathia Foundation for fellowships for A.C.F. and C. M. M., the SURF Rose Hills for support of L.B.P.-Z. through a summer research fellowship, Henry Jiang and Julia Oktawiec for experimental assistance, and Dr. Katie R. Meihaus for editorial assistance.

Contributor Information

Victor Y. Mao, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA)

Phillip J. Milner, Department of Chemistry, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA)

Jung-Hoon Lee, Department of Physics, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA); The Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 1 Cyclotron Rd., Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA); The Kavli Energy Nanosciences Institute, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA).

Alexander C. Forse, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA) Department of Chemistry, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA); Berkeley Energy and Climate Institute, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA).

Eugene J. Kim, Department of Chemistry, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA)

Rebecca L. Siegelman, Department of Chemistry, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA) Materials Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA).

C. Michael McGuirk, Department of Chemistry, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA).

Leo B. Porter-Zasada, University of California Berkeley, Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley, 94720 Berkeley, UNITED STATES

Jeffrey B. Neaton, Department of Physics, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA) The Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 1 Cyclotron Rd., Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA); The Kavli Energy Nanosciences Institute, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA).

Jeffrey A. Reimer, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA) Berkeley Energy and Climate Institute, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA).

Jeffrey R. Long, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA); Department of Chemistry, The University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA); Materials Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley CA, 94720 (USA).

References

- [1].N. US Department of Commerce, “ESRL Global Monitoring Division - Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network,” can be found under https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/,n.d.

- [2].O. US EPA, “Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2016,” can be found under https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks-1990-2016, 2018.

- [3].Rubin ES, Davison JE, Herzog HJ, International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2015, 40, 378–400. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Haszeldine RS, Science 2009, 325, 1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Titinchi SJ, Piet M, Abbo HS, Bolland O, Schwieger W, Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 8153–8160. [Google Scholar]

- [6].McDonald TM, Mason JA, Kong X, Bloch ED, Gygi D, Dani A, Crocellà V, Giordanino F, Odoh SO, Drisdell WS, et al. , Nature 2015, 519, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Siegelman RL, McDonald TM, Gonzalez MI, Martell JD, Milner PJ, Mason JA, Berger AH, Bhown AS, Long JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10526–10538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Strazisar BR, Anderson RR, White CM, Energy Fuels 2003, 17, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hefti M, Joss L, Bjelobrk Z, Mazzotti M, Faraday Discuss. 2016, 192, 153–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lee WR, Hwang SY, Ryu DW, Lim KS, Han SS, Moon D, Choi J, Hong CS, Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 744–751. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jo H, Lee WR, Kim NW, Jung H, Lim KS, Kim JE, Kang DW, Lee H, Hiremath V, Seo JG, et al. , ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Siegelman RL, Milner PJ, Forse AC, Lee J-H, Colwell KA, Neaton JB, Reimer JA, Weston SC, Long JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13171–13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kang M, Kim JE, Kang DW, Lee HY, Moon D, Hong CS, J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 8177–8183. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Milner PJ, Siegelman RL, Forse AC, Gonzalez MI, Runčevski T, Martell JD, Reimer JA, Long JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13541–13553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Forse AC, Milner PJ, Lee J-H, Redfearn HN, Oktawiec J, Siegelman RL, Martell JD, Dinakar B, Porter-Zasada LB, Gonzalez MI, et al. , J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 18016–18031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lv B, Guo B, Zhou Z, Jing G, Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 10728–10735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Milner PJ, Martell JD, Siegelman RL, Gygi D, Weston SC, Long JR, Chem. Sci. 2017, 9, 160–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Marti RM, Howe JD, Morelock CR, Conradi MS, Walton KS, Sholl DS, Hayes SE, J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 25778–25787. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Flaig RW, Osborn Popp TM, Fracaroli AM, Kapustin EA, Kalmutzki MJ, Altamimi RM, Fathieh F, Reimer JA, Yaghi OM, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12125–12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen C-H, Shimon D, Lee JJ, Didas SA, Mehta AK, Sievers C, Jones CW, Hayes SE, Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6553–6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mafra L, Čendak T, Schneider S, Wiper PV, Pires J, Gomes JRB, Pinto ML, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 389–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pinto ML, Mafra L, Guil JM, Pires J, Rocha J, Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee J-H, Siegelman RL, Maserati L, Rangel T, Helms BA, Long JR, Neaton JB, Chem Sci 2018, 9, 5197–5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Danon A, Stair PC, Weitz E, J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 11540–11549. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bossa J-B, Borget F, Duvernay F, Theulé P, Chiavassa T, J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 5113–5120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Masuda K, Ito Y, Horiguchi M, Fujita H, Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Khanna RK, Moore MH, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 1999, 55, 961–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Planas N, Dzubak AL, Poloni R, Lin L-C, McManus A, McDonald TM, Neaton JB, Long JR, Smit B, Gagliardi L, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7402–7405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vlaisavljevich B, Odoh SO, Schnell SK, Dzubak AL, Lee K, Planas N, Neaton JB, Gagliardi L, Smit B, Chemical Science 2015, 6, 5177–5185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mason JA, Oktawiec J, Taylor MK, Hudson MR, Rodriguez J, Bachman JE, Gonzalez MI, Cervellino A, Guagliardi A, Brown CM, et al. , Nature 2015, 527, 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang B, Xie L-H, Wang X, Liu X-M, Li J, Li J-R, Green Energy & Environment 2018, 3, 191–228. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Li J-R, Kuppler RJ, Zhou H-C, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1477–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.