Abstract

Emerging evidence indicates that mitochondria contribute to drug resistance in cancer. But how to selectively target the mitochondria of cancer cells remains less explored. Here we show perimitochondrial enzymatic self-assembly for selectively targeting the mitochondria of liver cancer cells. Nanoparticles of a peptide-lipid conjugate, being a substrate of enterokinase (ENTK), encapsulate chloramphenicol (CLRP), a clinically used antibiotic that is deactivated by glucuronidases in cytosol, but not in mitochondria. Perimitochondrial ENTK cleaves the Flag-tag on the conjugate to deliver CLRP selectively into the mitochondria of cancer cells, thus inhibiting the mitochondrial protein synthesis, inducing the release of cytochrome c into cytosol, and resulting in cancer cell death. This strategy selectively targets liver cancer cells over normal liver cells. Moreover, blocking the mitochondrial protein synthesis sensitizes the cancer cells, relying on glycolysis and/or OXPHOS, to cisplatin. This work illustrates a facile approach, selectively targeting mitochondria of cancer cells and repurposing clinically approved ribosome inhibitors, to interrupt the metabolism of cancer cells for cancer treatment.

Keywords: enzyme, self-assembly, peptide-lipid conjugate, mitochondrial protein synthesis, chloramphenicol

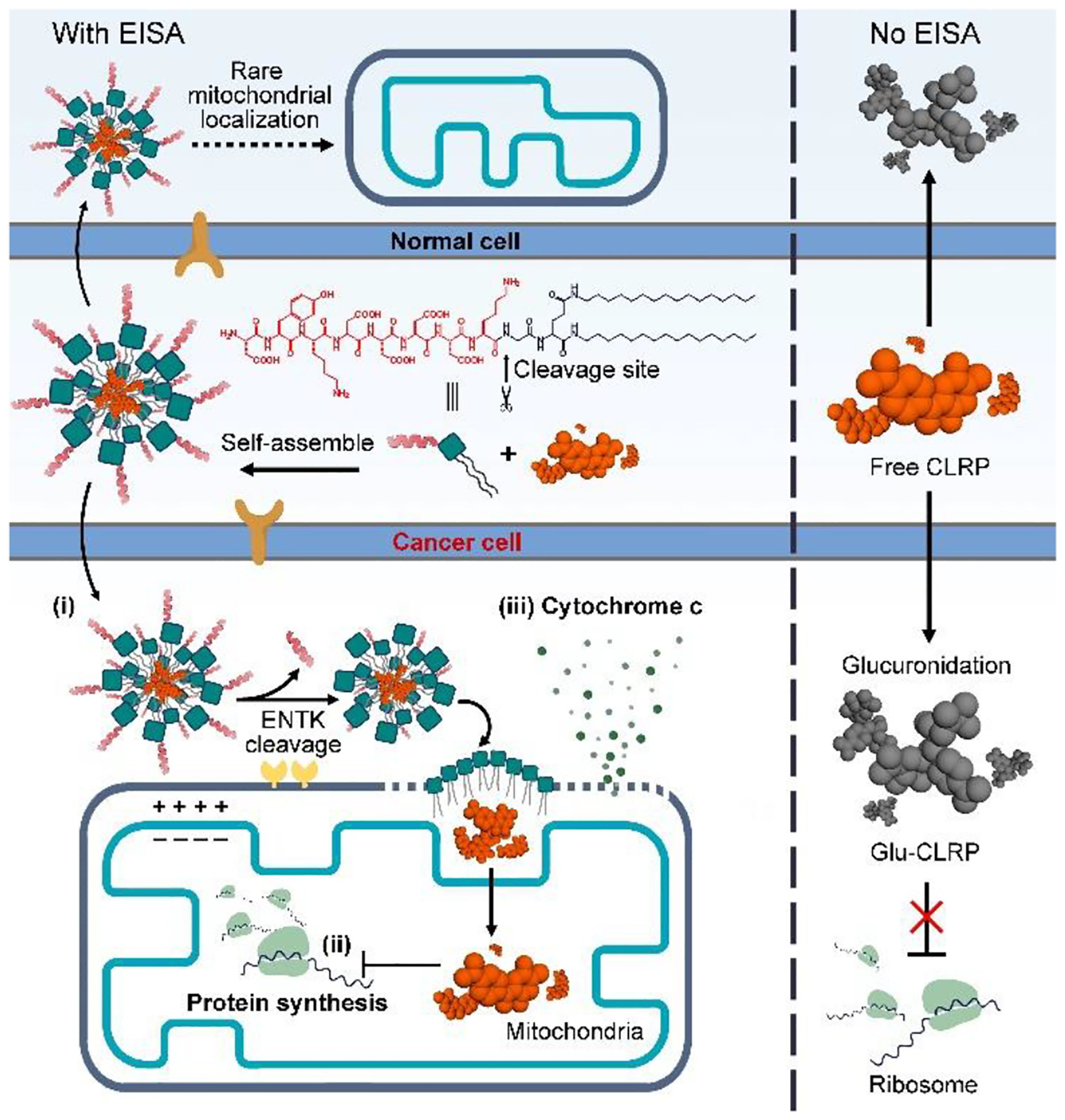

Graphical Abstract

Mitochondria are complex organelles that play a central role in key cellular processes, particularly in acting as the hub for bioenergetic, biosynthetic, and signaling events.1–7 Decades of researches have revealed that, in fact, many cancer cells depend on intact mitochondria OXPHOS and respiration for proliferation, tumorigenesis, and drug resistance.8–13 Thus, targeting the mitochondria of cancer cells would be an approach for probing physiological processes14 and killing cancer cells,15,16 as reported by previous studies.17–22 Moreover, the existence of protein synthesis machinery in mitochondria suggests that it is feasible to inhibit mitochondrial protein synthesis. Although most of the mitochondrial proteins are imported from cytoplasm, mitochondrial DNA encodes 13 critical proteins23 that are involved in various cellular activities, such as ATP synthesis,24–26 aerobic metabolism,27–29 NADH dehydrogenation and the electron transfer to ubiquinone.30 Thus, the inhibition of the protein synthesis inside the mitochondria of cancer cells disrupts mitochondrial metabolism, especially oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS),31 and eventually induces the death of cancer cells. Recent advance in the mitochondria biology reveals that mitochondria are dynamic and constantly undergo fission and fusion.32 Since these dynamic processes requires energy (e.g., ATP)33, reducing ATP production would disrupt mitochondria dynamics and inhibit cell proliferation. In addition, because mitochondria play important roles beyond bioenergetics, blocking mitochondrial protein synthesis would be lethal for cell proliferation.34,35 This concept has been demonstrated by Lisanti et al., who reported that antibiotics that target mitochondria effectively eradicate cancer stem cells.36

While increasing number of agents for targeting mitochondrial metabolism have been identified, how to selectively target the mitochondria of cancer cells without increasing side effects remains less explored.13 Recently, we found that enterokinase (ENTK/TMPRSS15),37,38 a transmembrane serine protease, also presents on the mitochondria of cancer cells.39 This observation allows the use of enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA),40–46 as a way, for selectively targeting mitochondria of cancer cells. Thus, we decide to use enzymatic reaction catalyzed by proteases (e.g., ENTK) for delivering chloramphenicol (CLRP) into the mitochondria of cancer cells, especially liver cancer cells, for inhibiting mitochondrial protein synthesis.47–49 We choose liver cancer cells for several reasons: (i) the incidence rates of liver cancer has tripled since 1980, but survival rate of liver cancer remains low (only 18%).50 Sorafenib is the most commonly used treatment for liver cancer, but its toxicity and unsatisfactory activity remain unsolved issues.51 Although immune checkpoint blockade was recently approved for treating liver cancers, considerable number of patients, especially the ones have virus-related liver cancers, are unable to benefit.52 Thus, there are urgent needs for approaches that selectively target liver cancer cells without harming normal cells. (ii) Liver cells detoxify CLRP via the glucuronidation53 catalyzed by a cytosolic enzyme. Since mitochondria lack the enzyme for glucuronidation (vide infra), delivering the CLRP into the mitochondria of liver cancer cells should inhibit mitochondrial protein synthesis, thus lead to selective death of cancer cells (Figure 1). Based on these rationales, we use perimitochondrial EISA to deliver CLRP into the mitochondria of HepG2 and HeLa cells. Because HepG2 is a liver carcinoma cell line that relies on glycolysis54–58 along with OXPHOS and HeLa mainly depends on OXPHOS59, this choice allows us to compare the inhibition of the cancer cells relying on different types of ATP supply (OXPHOS or glycolysis). To exam the side effect of CLRP on normal tissue, such as bone marrow suppression60 and liver damage61, we use HS-562 (bone marrow stromal cell) and AML1263 (normal liver cell), as the noncancerous cells, for control.

Figure 1.

Illustration of multiple functions of the EISA of Flag-(C16)2: (i) perimitochondrial accumulation, (ii) mitochondria-targeting drug delivery, and (iii) mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Molecular Design and Synthesis.

Figure 1 shows the structure of the designed peptide-lipid conjugate (Flag-(C16)2), which is a substrate of ENTK. The conjugate consists of (i) the Flag-tag (DYKDDDDK)64 as the substrate of ENTK for enzymatic recognition and cleavage and (ii) a lipid-like moiety (NH2-Glu-(C16)2) that enables molecular self-assembly to form micelles. Using Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis, we firstly produce the Flag-Gly moiety with protecting groups (Scheme S1). Subsequently, we connect the protected Flag-Gly to 2-amino-dibutylhexadecanediamide through C-terminal activation. Finally, the removal of all protecting groups and the purification by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) produce the designed Flag-(C16)2.

Selectively Targeting Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis in Cancer Cells.

Due to the presence of glucuronosyltransferase that detoxifies CLRP via glucuronidation,53 the treatment of CLRP alone hardly suppresses the viability of mammalian cells, including liver cancer cells (HepG2, Figure 2A). However, the combination of CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 (25 μM) exhibits significantly increased cytotoxicity against cancer cells but hardly affects the viability of the noncancerous cells (AML12 and HS-5) (Figures 2A and S1). To verify the inhibition of protein synthesis inside the mitochondria of the cancer cells, we evaluated the intracellular level of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (MT-COX-1), a protein encoded by mitochondrial genome and synthesized in mitochondria. Western blot analysis and immunofluorescent images show that the HepG2 and HeLa cells incubated with the mixture of CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 exhibit drastically reduced synthesis of MT-COX-1 compared to the cells treated by the solvent control (PBS), CLRP, or Flag-(C16)2 (Figures 2B and S2). However, the combination rarely aggravates the inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis by CLRP in HS-5 cells (Figure S2). This cancer cell specificity help reduce the side effects of CLRP, including bone marrow suppression60 and liver toxicity.61

Figure 2.

Combining Flag-(C16)2 and CLRP for inhibiting cancer cells. (A) IC50 of free CLRP and CLRP mixed with Flag-(C16)2 (25 μM) for HeLa, HepG2, AML12 and HS-5 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of MT-COX-1 level in HepG2 cells treated by solvent control (PBS), Flag-(C16)2 (50 μM, 24 h, p<0.01), free CLRP (100 μM, 24 h, p<0.001) and the mixture of CLRP (100 μM) and Flag-(C16)2 (50 μM, 24 h, p<0.001).

Disrupting Mitochondria Metabolism to Reduce MDR and Sensitize Cancer Cells for Cisplatin.

Because the proteins expressed by mitochondria are critical for OXPHOS,31 inhibiting the mitochondrial protein synthesis potently disrupts ATP production in mitochondria and undersupplies ATP for the whole cell, which eventually restrains cell proliferation. As shown in Figure 3, HepG2 cells incubated with the mixture of CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 show significant reduction of ATP level (visualized by an ATP probe65), in mitochondria (Figure 3A) and in the whole cell (Figure 3C), compared to the cells treated by the solvent control (PBS), CLRP, or Flag-(C16)2. These results suggest that Flag-(C16)2 selectively transports CLRP into the mitochondria of the cancer cells where the glucuronosyltransferase is absent (Figure S3). Inside the mitochondria, the CLRP inhibits mitochondrial protein synthesis, thus, impairing the mitochondrial bioenergetics (Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Combining Flag-(C16)2 and CLRP inhibits OXPHOS and Multidrug resistance (MDR). (A) Visualization of ATP (red) in HepG2 cells pretreated by solvent control (PBS), Flag-(C16)2 (50 μM, 24 h), free CLRP (50 μM, 24 h), and the mixture of CLRP (50 μM) and Flag-(C16)2 (50 μM, 24 h). (B) Fluorescence images of MDR assay in HepG2 cells pretreated by solvent control (PBS), Flag-(C16)2 (25 μM, 24 h), free CLRP (50 μM, 24 h), and the mixture of CLRP (50 μM) and Flag-(C16)2 (25 μM, 24 h). The higher fluorescence intensity, the more inhibition on MDR. (C) Relative whole cell ATP level in HepG2 cells treated by the condition in (A). (D) MDR assay in HepG2 cells treated by the condition in (B). (E) The 2nd day IC50 of cisplatin for HepG2 pretreated by solvent control (PBS), Flag-(C16)2 (25 μM, 24 h), free CLRP (50 μM, 24 h), and the mixture of CLRP (50 μM) and Flag-(C16)2 (25 μM, 24 h). Flag-(C16)2 and CLRP were removed after the pretreatment, immediately followed by adding cisplatin. Scale bar = 10 μm. ** means P<0.01, *** means P<0.001.

To exam whether targeting the mitochondrial energetics diminishes the drug resistance originating from the ATP-dependent drug efflux pumps in cancer treatment, we perform the multidrug resistance (MDR) assay on the HepG2 cells. Our results reveal that the combination of CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 efficiently reduces the drug efflux in HepG2 cells compared to the groups treated by PBS, free CLRP, or Flag-(C16)2 (Figure 3B and 3D, the higher intracellular fluorescence, the more inhibition on MDR). Because mitochondria involve in cisplatin resistance66 and efflux transporters67 that detoxify cisplatin, we use the combination of CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 to treat HepG2 cell before adding cisplatin. Our result shows that the combination of CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 substantially sensitizes HepG2 to cisplatin (Figure 3E). The effects of the Flag-tagged conjugate on HeLa cells resemble those on HepG2 cells. Because HeLa relies more on OXOPHOS, the whole cell ATP level drops more in HeLa cells than in HepG2 cells (Figure S4). Neither CLRP nor CLRP mixed with Flag-(C16)2 significantly change the MDR in normal cell line (HS-5, Figure S5), agreeing with the selectivity of EISA for targeting the mitochondria of cancer cells.

Physiochemical study.

Flag-(C16)2 self-assembles into nanoparticles at 50 μM (its critical micelle concentration (CMC) is 43 μM, Figure S6). The nanoparticles transform into larger micelle-like aggregates (made of Gly-Glu-(C16)2, Scheme S1 and Figure S7) upon the addition of ENTK (Figure 4A and S7). The Flag-lipid conjugates consist of a hydrophilic Flag tag and a hydrophobic lipid tail. Thus, in the assemblies, the Flag tag (hydrophilic “head” regions), which is the substrate of ENTK, would likely contact the surrounding solvent (water) in an aqueous solution. Thus, the enzymatic substrates unlikely would be buried within the nanostructures. Moreover, the data in Figure S7D reveals that ENTK hydrolyzes Flag-(C16)2 at 200 μM which is much greater than the CMC concentration of this molecule (CMC = 43 μM), indicating the cleavage can occur on the nanoparticles. Therefore, the hydrophilic Flag tags contact with the surrounding solvent in an aqueous solution, exposing the enzymatic substrate to ENTK, likely resulting in an efficient hydrolysis on the nanostructures. The nanostructures of assemblies largely depend on the self-assembly process.68,69 Thus, the microstructure in a direct suspension of Gly-Glu-(C16)2, the enzymatic product which has poor solubility, unlikely reflects the nanostructures formed by enzymatic conversion. Formulation study reveals that the loading efficiency (LE%) of CLRP in Flag-(C16)2 micelles is 10.9%, and the encapsulation capacity (EC) is 66.7 μg CLRP in per mg Flag-(C16)2 micelles. Stability test in biorelevant condition confirms that Flag-(C16)2 is degraded in HepG2 cell lysis (24 h, Figure S8), with a conversion rate around 30%. We found Flag-tag and Gly-Glu-(C16)2 from the enzymatic cleavage products in the cell lysis (Figure S8), indicating that Flag-(C16)2 undergoes proteolysis by ENTK in HepG2 cells.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial delivery of CLRP (in the form of CLRP-NBD) by Flag-(C16)2. (A) Static light scattering (SLS) analysis of Flag-(C16)2 (50 μM) before and after adding ENTK (24 h, 37 °C). (B) Fluorescent images of HepG2 cells incubated with Flag-(C14-NBD)2 (50 μM, 3 h). (C) Fluorescent images of HepG2 cells incubated with the mixture of CLRPs-NBD (100 μM) and Flag-(C16)2 (50 μM) for 8 h. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Mitochondrial delivery of CLRP.

To monitor the mitochondrial delivery of CLRP by the EISA of Flag-(C16)2, we labeled the peptide-lipid conjugate and CLRP by nitrobenzofurazan (NBD, an environmental sensitive fluorophore) to produce Flag-(C14-NBD)2 and CLRP-NBD, respectively (Scheme S1). Incubating HepG2 cells with Flag-(C14-NBD)2 results in the extensive overlap of the fluorescence from NBD with MitoTracker (Figure 4B), indicating that the Flag-tagged lipids specifically accumulate at the mitochondria of the liver cancer cells. But incubating Flag-(C14-NBD)2 with HS-5 or AML12 cells produces little fluorescence of NBD at the mitochondria of the cells (Figure S9). While HepG2 cells incubated with CLRP-NBD show punctate fluorescence in cytosol (Figure S10), the cells treated by the mixture of Flag-(C16)2 and CLRP-NBD exhibit fluorescence mainly at the mitochondria (Figure 4C) with scattered fluorescent puncta in cytosol, which may originate from the diffusion of the unencapsulated CLRPs-NBD (LE% is around 10%). The results confirm the mitochondrial distribution of CLRP via Flag-(C16)2 nanoparticles with limited leakage throughout the delivery and agree with the selective inhibition on the liver cancer cells (Figure 2). Moreover, high magnification images reveal that HepG2 cells incubated with Flag-(C14-NBD)2 exhibit intensive fluorescence in the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM, Figure S11), further confirming the perimitochondrial EISA. This observation also suggests that the CLRP-loading peptides can fuse into MOM, rupture the micelles, and transiently release CLRP upon arriving to mitochondria (Figure 1). The performances of the Flag-tagged lipids on HeLa cells resemble those on HepG2 cells (Figure S9 and S12). These results confirm that Flag-(C16)2, being able to target to the mitochondria of cancer cells, delivers the drugs (e.g., CLRP) selectively to the mitochondria of cancer cells.

Perimitochondrial EISA Disrupting Mitochondria Dynamics and Resulting in MOMP.

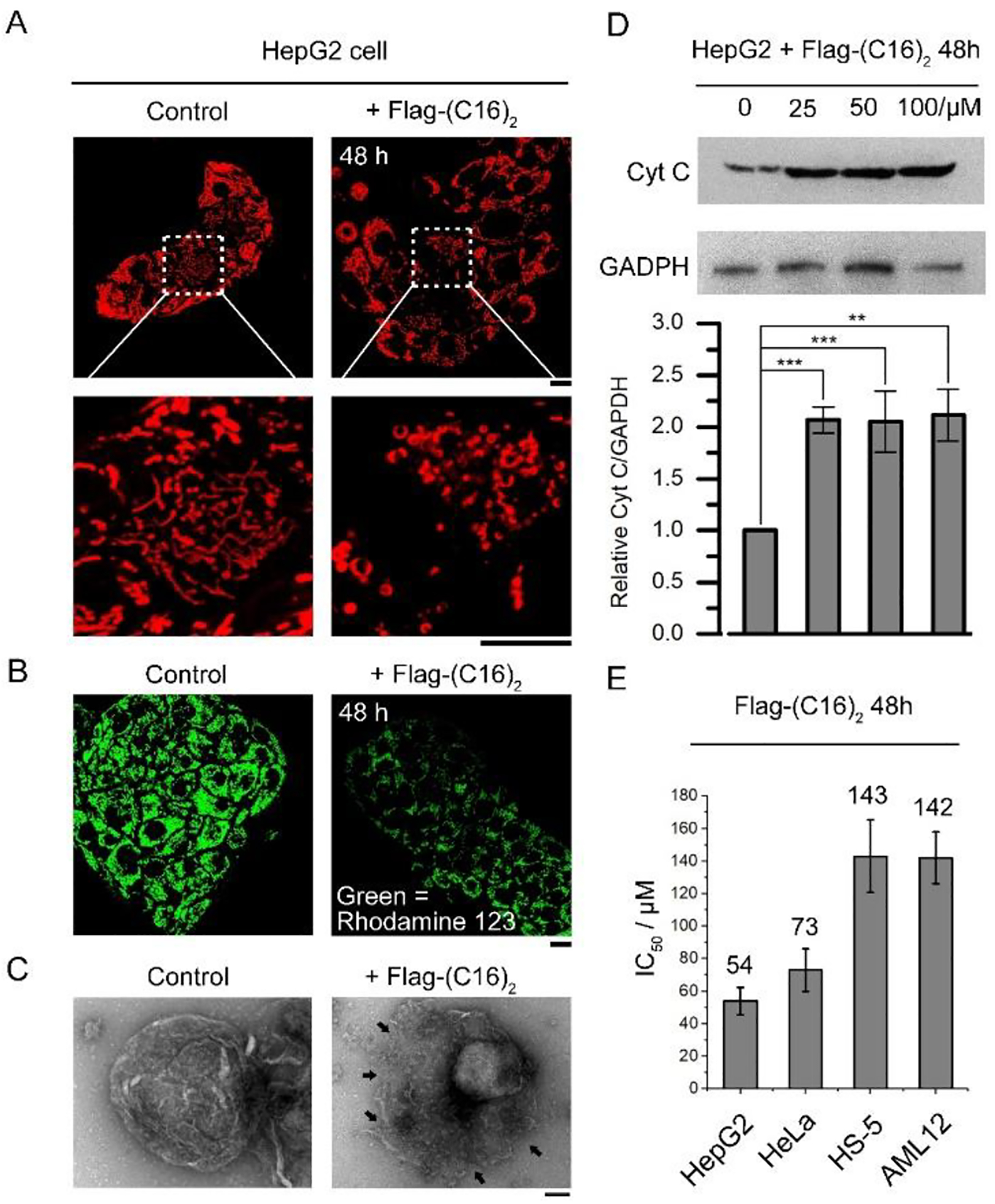

To elucidate the synergism (Figure S13) of Flag-(C16)2 and CLRP for inhibiting the growth of cancer cells (Figure 2A and S1), we studied the effect of Flag-(C16)2 on the cells. While being incubated with the culture medium, the cells exhibit tubular mitochondria, treating HepG2 or HeLa cells with Flag-(C16)2 for 48h, however, results in fragmental mitochondria (Figure 5A and S14), reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (as evidenced by the decreased mitochondrial fluorescence of Rhodamine 123,70 Figure 5B and S15), and the decrease of cell viability (Figure 5E and S16). These observations suggest a proapoptotic process in the cells.71,72 Since the cell apoptosis is the consequence of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization73 (MOMP), these results imply that mitochondrial proteases (e.g. ENTK) convert Flag-(C16)2 into more lipophilic micelles (made of Gly-Glu-(C16)2), which would merge with and destabilize MOM.

Figure 5.

The Flag-(C16)2 induces MOMP in cancer cells. (A) Flag-(C16)2 induces mitochondria (stained by MitoTracker) fragmentation in HepG2 cells. (B) Evaluation of the mitochondrial membrane potential in HepG2 cells incubated with 50 μM Flag-(C16)2 for 48 h. Scale bar = 10 μm. (C) TEM images of the mitochondria isolated from HepG2 cells incubated in culture medium (left) and Flag-(C16)2 mixed (50 μM, 48 h) medium (right). The mitochondrial damages are indicated by arrows. Scale bar = 100 nm. (D) Western blot analysis of the cytochrome c in the cytosol fraction from HepG2 cells incubated with 100, 50, 25 and 0 μM Flag-(C16)2 for 48 h. ** means P<0.01, *** means P<0.001. (E) IC50 (2nd day) of Flag-(C16)2 for HepG2, HeLa, AML12 and HS-5 cell.

To confirm the MOMP caused by Flag-(C16)2, we isolated mitochondria from HepG2 cells incubated with Flag-(C16)2. The cells treated by Flag-(C16)2 produce mitochondria with rough and broken surface (Figure 5C, indicated by arrows), while the mitochondria from the HepG2 cells incubated with only the culture medium exhibit integral mitochondrial membrane (Figure 5C). Moreover, Western blot analysis reveals increased cytochrome c in the cytosols of HepG2 and HeLa cells that are treated by Flag-(C16)2 at different concentration (Figure 5D and S17), validating the permeabilization of mitochondrial outer membrane.74 On the contrary, Flag-(C16)2 hardly induces cell death in normal cells (HS-5 and AML12, Figures 5E and S16), which agrees with the observed cancer cell specificity. Thus, together with MOMP promoted by Flag-(C16)2, the inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis (by CLRP) synergistically reduces the viability of cancer cells (Figure 1).

Factors for Cancer Specificity.

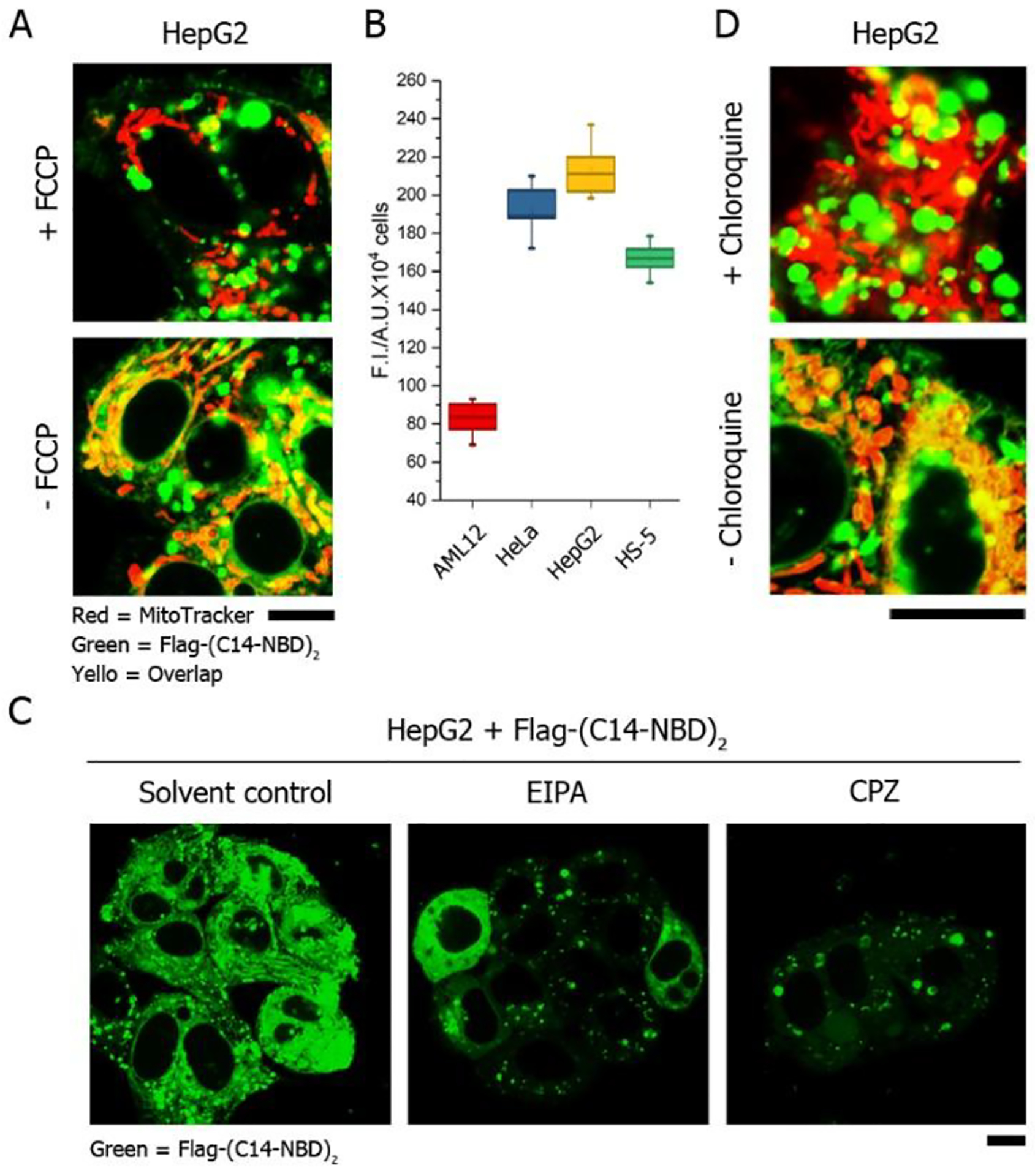

Connecting the D-enantiomer of Flag-tag, which resists ENTK, to the lipid diminishes the mitochondria-specific accumulation and CLRP delivery (Figures S18). The result suggests that the enzymatic cleavage by ENTK is critical for the Flag-tagged lipids to target to mitochondria. Moreover, pretreating the HepG2 cell with FCCP75 (mitochondria depolarizer) results in less mitochondrial retention of the Flag-tagged lipids (Figure 6A and S19), indicating that the mitochondrial polarization state is important for the peptide-lipid conjugates to approach mitochondria. Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential confirms that the mitochondria in cancer cells are more polar than those in noncancerous cells (Figure 6B). Immunofluorescence imaging confirms the presence of ENTK in the mitochondria of cancer cells (HepG2 and HeLa, Figure S20). Compared to cancer cells, the normal cells either lack mitochondrial ENTK (e.g., HS-5, Figure S19) or generate less polarized mitochondria (e.g., AML12, Figure 6B). The mitochondrial proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane is essential for the mitochondrial polarization76. With the results above, we believe that the Flag-lipid assemblies, carrying negative charges, are protonated on MOM, which neutralizes the negative charges and increase the lipophilicity of the assembles, forcing the Flag-lipid conjugates to adhere to MOM. The mitochondrial ENTK remove the Flag tags from the peptide-lipid assemblies, generating products that tend to integrate with MOM. These results suggest that both enzymatic reaction and the high mitochondrial membrane potential76 of the cancer cells result in the cancer cell specificity of Flag-(C16)2 and its derivatives.

Figure 6.

Mechanism study of mitochondrial targeting and endocytosis. (A) Fluorescent images of HepG2 cells incubated with Flag-(C14-NBD)2 in the presence of FCCP. (B) Comparation of mitochondrial membrane potential in HeLa, HepG2, HS-5 and AML12 cells by Rhodamine 123. (C) Fluorescent images of HepG2 cells incubated with Flag-(C14-NBD)2 in the presence of endocytosis inhibitors (EIPA for micropinocytosis and CPZ for clathrin-dependent endocytosis). (D) Fluorescent images of HepG2 cells incubated with Flag-(C14-NBD)2 in the presence of chloroquine. The concentration of Flag-(C14-NBD)2 is 50 μM, incubation time is 2 h. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Modes of Endocytosis.

The pretreatment of 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA) or chlorpromazine (CPZ) extensively inhibits the cellular uptake of Flag-(C14-NBD)2 (Figure 6C), suggesting that the intracellular internalization of the Flag-tagged lipids relies on macropinocytosis (inhibited by EIPA77) and clathrin-mediated endocytosis (inhibited by CPZ78). Moreover, the preincubation of chloroquine (endosomal acidification inhibitor79) results in significantly reduced fluorescence of Flag-(C14-NBD)2 in the mitochondria but more fluorescence in the lysosome of cells (Figure 6D and S21), indicating that the pH-buffering effect80 of the carboxylic groups in Flag-tag facilitate the endosomal escape.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we demonstrated the use of perimitochondrial enzymatic reaction of Flag-tagged lipids for selectively targeting the mitochondria of cancer cells, especially liver cancer cells. Although the lipid-peptide conjugate forms micelles before enzymatic reaction, an assembly process occurs while mitochondrial ENTK cleaves the Flag tags off the lipid. Therefore, enzymatic self-assembly, indeed, occurs on mitochondria. The basis for cancer cell selectivity is that Flag-(C16)2, as a substrate of perimitochondrial EISA, delivers CLRP into the mitochondria of cancer cells, but not into the mitochondria of normal cells. Thus, CLRP potently inhibit the mitochondrial protein synthesis to disrupt mitochondria metabolism. The origins of the selectivity are the enzymatic reaction catalyzed by the ENTK on the surface of mitochondria and mitochondrial polarization state. Moreover, the peptide-lipid conjugates, after the cleavage of the Flag-tag, permeabilize the mitochondria of cancer cells for apoptosis in cancer cells. Introducing enzymatic responsiveness to peptide derivatives,43,81–84 including peptide amphiphiles,85–89 is emerging as a powerful approach for selectively targeting cancer cells.90 This enzymatic approach should be useful for designing other peptides for cellular drug delivery.91 As a multifunctional molecule that integrates enzymatic reaction, self-assembly, and membrane disruption, the Flag-tagged lipids achieve the spatial control of inhibitor in subcellular space (e.g., mitochondria) for selectively targeting liver cancer cells over normal cells. Controlling the emergent properties of molecular assemblies, this work offers an approach for repurposing other clinically approved ribosome inhibitors to target mitochondria and to interrupt the metabolism92 of cancer cells for reducing cancer drug resistance.

EXPERIMENT SECTION

Materials.

All amino acid derivatives involved in the synthesis were purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai) Ltd. N, N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) and O-benzotriazole-N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyluronium-hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. The synthesis of all peptide fragments was based on solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). The peptides were made via the combination of SPPS and solution phase synthesis. All crude compounds were purified by HPLC with the yield of 70–80%. All reagents and solvents were used as received without further purification unless otherwise stated. All cell lines were purchased from ATCC. All media for cell culture were purchased from ATCC, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin from Gibco by Life technologies, and 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) from ACROS Organics. Mitochondria isolation kit was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The mitochondria were isolated according to the protocol provided by the company. All antibodies were purchased from Abcam.

Instruments.

All peptides were purified by Water Agilent 1100 HPLC system, equipped with an XTerra C18 RP column. LC-MS was operated on a Waters Acquity Ultra Performance LC with Waters MICRO-MASS detector. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were taken on Morgagni 268 transmission electron microscope. Fluorescent analysis was performed on Shimadzu RF-5301-PC fluorescence spectrophotometer. Fluorescence images were taken by ZEISS LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope.

Peptide Synthesis.

The synthesis of Flag-tag-Gly-OH was done by Fmoc-based solid phase synthesis. The synthesis route of Flag-(C16)2 and its derivatives were shown in Scheme S2 to S4. Briefly, the carboxylic groups in Fmoc-Glu-OH were activated by a mixture (1:1 molar ratio) of DCC and NHS in the presence of triethylamine (TEA) at room temperature for 30 min. After the activation, NH2-C16 or NH2-C14-NBD were mixed into the solution. The mixtures were kept at room temperature for overnight. Piperidine was used to remove the Fmoc protection group. HPLC was used to purify the resulted lipids. The C-terminus in the Flag-tag-Gly-OH was activated by DCC and NHS in the presence of TEA at room temperature for 30 min. After the activation, the synthesized lipids were mixed into the Flag-tag solution. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for overnight. Piperidine and trifluoroacetic acid were used to remove all protection groups. HPLC was used to purify the final products.

Cell Culture.

HeLa and HepG2 cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 0.5% (vol/vol) penicillin (10, 000 unit), and 0.5% (vol/vol) streptomycin (10, 000 unit). HS-5 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Media (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 0.5% (vol/vol) penicillin (10, 000 unit), and 0.5% (vol/vol) streptomycin (10, 000 unit). AML12 cells were cultured in DMEM: F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 μg/mL insulin, 5.5 μg/mL transferrin, 5 ng/ml selenium and 40 ng/mL dexamethasone. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were plated on confocal dishes (CellVis) and fixed in 4 wt% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20. Fixed cells were incubated in primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, washed three times for 5 min each, incubated in secondary antibody for 1 h, then washed three times for 5 min each.

Western Blot.

Total protein extracts were prepared in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, CATALOG # 9803S) followed by 5 freeze-thaw circles. Protein concentration was determined by Coomassie Blue method. Protein extracts (20 μg per lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Western blotting was performed according to standard protocols2. Gel analysis was conducted using ImageJ.

Determination of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potentials by Rhodamine 123.

Cells were firstly incubated with Rhodamine 123 (10 μg/mL) for 1h. After 1h of incubation, cells were washed by fresh medium for 5 times to remove the excess Rhodamine 123. Then, cells were incubated in fresh culture medium for another 24h. Before the detection of intracellular Rhodamine 123, cells were detached from petri dishes (via trypsin) and washed 3 times by PBS. The cell suspensions were diluted into 105 cells/mL. 1 mL cell suspension was added into cuvette. The fluorescence intensity of the intracellular Rhodamine 123 was then determined by Shimadzu RF-5301-PC fluorescence spectrophotometer. λex ∼504 nm; λem ∼534 nm. PBS was used as the blank control.

Determination of the Drug Loading Efficiency (LE%) and Encapsulation Capacity (EC).

To facilitate the detection of CLRP, we connected NBD to the molecule (CLRPs-NBD). A mixture of CLRPs-NBD (100 μM) and Flag-(C16)2 (50 μM) were prepared. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for more than two hours for equilibrium. High-speed centrifuge (12,000Xg, 1h) was applied to spin down the Flag-(C16)2 nanoparticles encapsulating CLRPs-NBD (Figure S23). Free CLRPs-NBD was unable to precipitate (Figure S23). The CLRPs-NBD concentrations in the supernatant before and after the centrifuge were determined by fluorometer according to a standard curve (Figure S21). The LE% was determined by ([CLRPs-NBD]0-[CLRPs-NBD]t)/[CLRPs-NBD]0X100%, where [CLRPs-NBD]0 and [CLRPs-NBD]t are the concentration of CLRPs-NBD in the supernatant before and after centrifuge. With the result of LE%, the EC can be determined. EC is defined by the mass (μg) of CLRP in per mg Flag-(C16)2 nanoparticles.

Quantification of Whole Cell ATP.

The ATP assay kit was purchased from Abcam (ab83355). The quantification of whole cell ATP was performed according to the manufacture’s protocol.

Multidrug Resistance (MDR) Assay.

The MDR assay kit was purchased from Abcam (ab112142). The evaluation of MDR after the treatment of PBS, Flag-(C16)2, CLRP and the mixture of CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 was performed according to the manufacture’s protocol.

Imaging ATP in cells.

The ATP probe (ATP-Red) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (SCT045). The visualization of ATP in cells was performed following the manufacture’s protocol. Zeiss 880 confocal fluorescence microscope was used for imaging.

Statistical analysis.

Data presented are means ± SD. Significance levels are calculated using t-test analysis. The ANOVA for multiple comparisons is done via single-factor ANOVA analysis (α=0.05). Results show that the “F value” is always larger than the “F critical value” when we are comparing the data collected from the groups treated by “Flag-(C16)2 + CLRP” to the data collected from the groups treated by PBS, free CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 alone, respectively. This confirms that the data collected from the groups treated by “Flag-(C16)2 + CLRP” is significantly different from the one collected from the groups treated by PBS, free CLRP and Flag-(C16)2 alone. All tests were analyzed from n > 3 independent experiments per condition.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was partially supported by NIH (R01CA142746) and NSF (MRSEC-1420382).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental details on the synthesis and characterization and figures supplementing the conclusion and hypothesis of this work are provided in the Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Green DR; Kroemer G, The Pathophysiology of Mitochondrial Cell Death. Science 2004, 305, 626–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).McBride HM; Neuspiel M; Wasiak S, Mitochondria: More than Just a Powerhouse. Curr. Biol 2006, 16, R551–R560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kujoth GC; Hiona A; Pugh TD; Someya S; Panzer K; Wohlgemuth SE; Hofer T; Seo AY; Sullivan R; Jobling WA; Morrow JD; Van Remmen H; Sedivy JM; Yamasoba T; Tanokura M; Weindruch R; Leeuwenburgh C; Prolla TA, Mitochondrial DNA Mutations, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis in Mammalian Aging. Science 2005, 309, 481–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Balaban RS; Nemoto S; Finkel T, Mitochondria, Oxidants, and Aging. Cell 2005, 120, 483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Pattingre S; Tassa A; Qu X; Garuti R; Liang XH; Mizushima N; Packer M; Schneider MD; Levine B, Bcl-2 Antiapoptotic Proteins Inhibit Beclin 1-Dependent Autophagy. Cell 2005, 122, 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Green; John C; nbsp; Reed DR, Mitochondria and Apoptosis. Science 1998, 281, 1309–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Nunnari J; Suomalainen A, Mitochondria: In Sickness and in Health. Cell 2012, 148, 1145–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wallace DC, Mitochondria and Cancer. Nat. Rew. Cancer 2012, 12, 685–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lee KM; Giltnane JM; Balko JM; Schwarz LJ; Guerrero-Zotano AL; Hutchinson KE; Nixon MJ; Estrada MV; Sánchez V; Sanders ME; Lee T; Gómez H; Lluch A; Pérez-Fidalgo JA; Wolf MM; Andrejeva G; Rathmell JC; Fesik SW; Arteaga CL, MYC and MCL1 Cooperatively Promote Chemotherapy-Resistant Breast Cancer Stem Cells via Regulation of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 633–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Guerra F; Arbini AA; Moro L, Mitochondria and Cancer Chemoresistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2017, 1858, 686–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Bosc C; Selak MA; Sarry JE, Resistance Is Futile: Targeting Mitochondrial Energetics and Metabolism to Overcome Drug Resistance in Cancer Treatment. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 705–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zu XL; Guppy M, Cancer Metabolism: Facts, Fantasy, and Fiction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2004, 313, 459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Weinberg SE; Chandel NS, Targeting Mitochondria Metabolism for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol 2015, 11, 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lan G; Ni K; You E; Wang M; Culbert A; Jiang X; Lin W, Multifunctional Nanoscale Metal-Organic Layers for Ratiometric pH and Oxygen Sensing. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 18964–18969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Murphy MP, Targeting Lipophilic Cations To Mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2008, 1777, 1028–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Vyas S; Zaganjor E; Haigis MC, Mitochondria and Cancer. Cell 2016, 166, 555–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kang BH; Plescia J; Dohi T; Rosa J; Doxsey SJ; Altieri DC, Regulation of Tumor Cell Mitochondrial Homeostasis by an Organelle-Specific HSP90 Chaperone Network. Cell 2007, 131, 257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yasueda Y; Tamura T; Fujisawa A; Kuwata K; Tsukiji S; Kiyonaka S; Hamachi I, A Set of Organelle-Localizable Reactive Molecules for Mitochondrial Chemical Proteomics in Living Cells and Brain Tissues. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7592–7602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Marrache S; Pathak RK; Dhar S, Detouring of Cisplatin to Access Mitochondrial Genome for Overcoming Resistance. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2014, 111, 10444–10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wang H; Feng Z; Wang Y; Zhou R; Yang Z; Xu B, Integrating Enzymatic Self-Assembly and Mitochondria Targeting for Selectively Killing Cancer Cells without Acquired Drug Resistance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 16046–16055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hoye AT; Davoren JE; Wipf P; Fink MP; Kagan VE, Targeting Mitochondria. Acc. Chem. Res 2008, 41, 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Jean SR; Ahmed M; Lei EK; Wisnovsky SP; Kelley SO, Peptide-Mediated Delivery of Chemical Probes and Therapeutics to Mitochondria. Acc. Chemical Res 2016, 49, 1893–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).D’Souza AR; Minczuk M, Mitochondrial Transcription and Translation: Overview. Essays Biochem. 2018, 62, 309–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Čížková A; Stránecký V; Mayr JA; Tesařová M; Havlíčková V; Paul J; Ivánek R; Kuss AW; Hansíková H; Kaplanová V, Tmem70 Mutations Cause Isolated ATP Synthase Deficiency and Neonatal Mitochondrial Encephalocardiomyopathy. Nat. Genet 2008, 40, 1288–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Schon EA; Santra S; Pallotti F; Girvin ME, Pathogenesis of Primary Defects in Mitochondrial ATP Synthesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 2001, 12, 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Jonckheere AI; Smeitink JA; Rodenburg RJ, Mitochondrial ATP Synthase: Architecture, Function and Pathology. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis 2012, 35, 211–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Chandel NS; Budinger GS; Choe SH; Schumacker PT, Cellular Respiration during Hypoxia Role of Cytochrome Oxidase as the Oxygen Sensor in Hepatocytes. J. Bio. Chem 1997, 272, 18808–18816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Steffens G; Buse G, Studies on Cytochrome C Oxidase, IV [1--3]. Primary Structure and Function of Subunit II. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem 1979, 360, 613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Capaldi RA, Structure and Function of Cytochrome C Oxidase. Annu. Rev. Biochem 1990, 59, 569–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Brandt U, Energy Converting Nadh: Quinone Oxidoreductase (Complex I). Annu. Rev. Biochem 2006, 75, 69–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Schon EA, Mitochondrial Genetics and Disease. Trends Biochem. Sci 2000, 25, 555–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Friedman JR; Lackner LL; West M; DiBenedetto JR; Nunnari J; Voeltz GK, Er Tubules Mark Sites of Mitochondrial Division. Science 2011, 334, 358–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kraus F; Ryan MT, The Constriction and Scission Machineries Involved in Mitochondrial Fission. J. Cell Sci 2017, 130, 2953–2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Nagiec EE; Wu L; Swaney SM; Chosay JG; Ross DE; Brieland JK; Leach KL, Oxazolidinones Inhibit Cellular Proliferation via Inhibition of Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2005, 49, 3896–3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).van den Bogert C; Dontje BH; Holtrop M; Melis TE; Romijn JC; van Dongen JW; Kroon AM, Arrest of the Proliferation of Renal and Prostate Carcinomas of Human Origin by Inhibition of Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 3283–3289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lamb R; Ozsvari B; Lisanti CL; Tanowitz HB; Howell A; Martinez-Outschoorn UE; Sotgia F; Lisanti MP, Antibiotics That Target Mitochondria Effectively Eradicate Cancer Stem Cells, across Multiple Tumor Types: Treating Cancer Like an Infectious Disease. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 4569–4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kunitz M, Formation of Trypsin from Crystalline Trypsinogen by Means of Enterokinase. J. Gen. Physiol 1939, 22, 429–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Antalis TM; Buzza MS; Hodge KM; Hooper JD; Netzel-Arnett S, The Cutting Edge: Membrane-Anchored Serine Protease Activities in the Pericellular Microenvironment. Biochem. J 2010, 428, 325–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).He H; Wang J; Wang H; Zhou N; Yang D; Green DR; Xu B, Enzymatic Cleavage of Branched Peptides for Targeting Mitochondria. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 1215–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Li J; Kuang Y; Shi J; Zhou J; Medina JE; Zhou R; Yuan D; Yang C; Wang H; Yang Z, Enzyme‐Instructed Intracellular Molecular Self‐Assembly to Boost Activity of Cisplatin against Drug‐Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 13307–13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Cong Y; Ji L; Gao YJ; Liu FH; Cheng DB; Hu Z; Qiao ZY; Wang H, Microenvironment‐Induced In Situ Self‐Assembly of Polymer–Peptide Conjugates That Attack Solid Tumors Deeply. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 4632–4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Yao Q; Huang Z; Liu D; Chen J; Gao Y, Enzyme-Instructed Supramolecular Self-Assembly with Anticancer Activity. Adv. Mater 2019, 31, 1804814–1804821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Gao J; Zhan J; Yang Z, Enzyme-Instructed Self-Assembly (EISA) and Hydrogelation of Peptides. Adv. Mater 2020, 32, 1805798–1805811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yuan Y; Wang L; Du W; Ding Z; Zhang J; Han T; an L; Zhang H; Liang G, Intracellular Self-Assembly of Taxol Nanoparticles for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 9700–9704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zhan J; Cai Y; He S; Wang L; Yang Z, Tandem Molecular Self-Assembly in Liver Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 1813–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Hugo‐Wissemann D; Anundi I; Lauchart W; Viebahn R; Groot H, Differences in Glycolytic Capacity and Hypoxia Tolerance between Hepatoma Cells and Hepatocytes. Hepatology 1991, 13, 297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).To TL; Cuadros AM; Shah H; Hung WH; Li Y; Kim SH; Rubin DH; Boe RH; Rath S; Eaton JK, A Compendium of Genetic Modifiers of Mitochondrial Dysfunction Reveals Intra-Organelle Buffering. Cell 2019, 179, 1222–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Freeman K, Inhibition of Mitochondrial and Bacterial Protein Synthesis by Chloramphenicol. Can. J. Biochem 1970, 48, 479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Denslow N; O’Brien T, Susceptibility of 55s Mitochondrial Ribosomes to Antibiotics Inhibitory to Prokaryotic Ribosomes, Lincomycin, Chloramphenicol and PA114A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1974, 57, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Iwata S; Ostermeier C; Ludwig B; Michel H, Structure at 2.8 Å Resolution of Cytochrome C Oxidase from Paracoccus Denitrificans. Nature 1995, 376, 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Kudo M, Systemic Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2017 Update. Oncology 2017, 93 Suppl 1, 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Liu X; Qin S, Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Opportunities and Challenges. Oncologist 2019, 24, S3–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Chen M; LeDuc B; Kerr S; Howe D; Williams DA, Identification of Human UGT2B7 as the Major Isoform Involved in the O-Glucuronidation of Chloramphenicol. Drug Metab. Dispos 2010, 38, 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Hugo‐Wissemann D; Anundi I; Lauchart W; Viebahn R; de Groot H, Differences in Glycolytic Capacity and Hypoxia Tolerance between Hepatoma Cells and Hepatocytes. Hepatology 1991, 13, 297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Kuang Y; Han X; Xu M; Yang Q, Oxaloacetate Induces Apoptosis in HepG2 Cells via Inhibition of Glycolysis. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 1416–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Li M; Jin R; Wang W; Zhang T; Sang J; Li N; Han Q; Zhao W; Li C; Liu Z, STAT3 Regulates Glycolysis via Targeting Hexokinase 2 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 24777–24784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Kamalian L; Chadwick AE; Bayliss M; French NS; Monshouwer M; Snoeys J; Park BK, The Utility of HepG2 Cells to Identify Direct Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Absence of Cell Death. Toxicol. In Vitro 2015, 29, 732–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Marroquin LD; Hynes J; Dykens JA; Jamieson JD; Will Y, Circumventing the Crabtree Effect: Replacing Media Glucose with Galactose Increases Susceptibility of HepG2 Cells to Mitochondrial Toxicants. Toxicol. Sci 2007, 97, 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Zheng J, Energy Metabolism of Cancer: Glycolysis versus Oxidative Phosphorylation. Oncology Lett. 2012, 4, 1151–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).McCurdy PR, Chloramphenicol Bone Marrow Toxicity. JAMA 1961, 176, 588–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Suhrland LG; Weisberger AS, Chloramphenicol Toxicity in Liver and Renal Disease. Arch. Intern. Med 1963, 112, 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Roecklein BA; Torok-Storb B, Functionally Distinct Human Marrow Stromal Cell Lines Immortalized by Transduction with the Human Papilloma Virus E6/E7 Genes. Blood 1995, 85, 997–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Wu JC; Merlino G; Fausto N, Establishment and Characterization of Differentiated, Nontransformed Hepatocyte Cell Lines Derived from Mice Transgenic for Transforming Growth Factor Alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1994, 91, 674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Hopp TP; Prickett KS; Price VL; Libby RT; March CJ; Cerretti DP; Urdal DL; Conlon PJ, A Short Polypeptide Marker Sequence Useful for Recombinant Protein Identification and Purification. Nat. Biotechnol 1988, 6, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Wang L; Yuan L; Zeng X; Peng J; Ni Y; Er JC; Xu W; Agrawalla BK; Su D; Kim B, A Multisite‐Binding Switchable Fluorescent Probe for Monitoring Mitochondrial ATP Level Fluctuation in Live Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 1773–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Cocetta V; Ragazzi E; Montopoli M, Mitochondrial Involvement in Cisplatin Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2019, 20, 3384–3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Safaei R; Otani S; Larson BJ; Rasmussen ML; Howell SB, Transport of Cisplatin by the Copper Efflux Transporter ATP7B. Mol. Pharmacol 2008, 73, 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Zhao F; Gao Y; Shi J; Browdy HM; Xu B, Novel Anisotropic Supramolecular Hydrogel with High Stability over a Wide Ph Range. Langmuir 2011, 27, 1510–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Yang Z; Liang G; Wang L; Xu B, Using a Kinase/Phosphatase Switch to Regulate a Supramolecular Hydrogel and Forming the Supramolecular Hydrogel In Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 3038–3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Johnson LV; Walsh ML; Bockus BJ; Chen LB, Monitoring of Relative Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Living Cells by Fluorescence Microscopy. J. Cell Bio 1981, 88, 526–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Arnoult D, Mitochondrial Fragmentation in Apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2007, 17, 6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Ly JD; Grubb DR; Lawen A, The Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (Δψ M) in Apoptosis; an Update. Apoptosis 2003, 8, 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Kroemer G; Galluzzi L; Brenner C, Mitochondrial Membrane Permeabilization in Cell Death. Physiol. Rev 2007, 87, 99–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Garrido C; Galluzzi L; Brunet M; Puig P; Didelot C; Kroemer G, Mechanisms of Cytochrome C Release from Mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 1423–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Perry SW; Norman JP; Barbieri J; Brown EB; Gelbard HA, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Probes and the Proton Gradient: A Practical Usage Guide. Biotechniques 2011, 50, 98–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Chen LB, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Living Cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol 1988, 4, 155–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Nakase I; Niwa M; Takeuchi T; Sonomura K; Kawabata N; Koike Y; Takehashi M; Tanaka S; Ueda K; Simpson JC, Cellular Uptake of Arginine-Rich Peptides: Roles for Macropinocytosis and Actin Rearrangement. Mol. Ther 2004, 10, 1011–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Wang L-H; Rothberg KG; Anderson R, Mis-Assembly of Clathrin Lattices on Endosomes Reveals a Regulatory Switch for Coated Pit Formation. J. Bio. Chem 1993, 123, 1107–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Steinman RM; Mellman IS; Muller WA; Cohn ZA, Endocytosis and the Recycling of Plasma Membrane. J. Cell Bio 1983, 96, 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Varkouhi AK; Scholte M; Storm G; Haisma HJ, Endosomal Escape Pathways for Delivery of Biologicals. J. Control Release 2011, 151, 220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Yang Z; Gu H; Fu D; Gao P; Lam JK; Xu B, Enzymatic Formation of Supramolecular Hydrogels. Adv. Mater 2004, 16, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar]

- (82).Toledano S; Williams RJ; Jayawarna V; Ulijn RV, Enzyme-Triggered Self-Assembly of Peptide Hydrogels via Reversed Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 1070–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Wu C; Zhang R; Du W; Cheng L; Liang G, Alkaline Phosphatase-Triggered Self-Assembly of Near-Infrared Nanoparticles for the Enhanced Photoacoustic Imaging of Tumors. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7749–7754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Ye D; Shuhendler AJ; Cui L; Tong L; Tee SS; Tikhomirov G; Felsher DW; Rao J, Bioorthogonal Cyclization-Mediated In Situ Self-Assembly of Small-Molecule Probes for Imaging Caspase Activity In Vivo. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Tanaka A; Fukuoka Y; Morimoto Y; Honjo T; Koda D; Goto M; Maruyama T, Cancer Cell Death Induced by the Intracellular Self-Assembly of an Enzyme-Responsive Supramolecular Gelator. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Acar H; Samaeekia R; Schnorenberg MR; Sasmal DK; Huang J; Tirrell MV; LaBelle JL, Cathepsin-Mediated Cleavage of Peptides from Peptide Amphiphiles Leads to Enhanced Intracellular Peptide Accumulation. Bioconjug. Chem 2017, 28, 2316–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Webber MJ; Newcomb CJ; Bitton R; Stupp SI, Switching of Self-Assembly in a Peptide Nanostructure with a Specific Enzyme. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 9665–9672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Yuan Y; Sun H; Ge S; Wang M; Zhao H; Wang L; an L; Zhang J; Zhang H; Hu B, Controlled Intracellular Self-Assembly and Disassembly of 19f Nanoparticles for Mr Imaging of Caspase 3/7 in Zebrafish. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Tan J; Zhang M; Hai Z; Wu C; Lin J; Kuang W; Tang H; Huang Y; Chen X; Liang G, Sustained Release of Two Bioactive Factors from Supramolecular Hydrogel Promotes Periodontal Bone Regeneration. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5616–5622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Feng Z; Han X; Wang H; Tang T; Xu B, Enzyme-Instructed Peptide Assemblies Selectively Inhibit Bone Tumors. Chem 2019, 5, 2442–2449.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Faraji AH; Wipf P, Nanoparticles in Cellular Drug Delivery. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2009, 17, 2950–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Warburg O, On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.