Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is an immunosuppressive, lethal brain tumor. Despite advances in molecular understanding and therapies, the clinical benefits have remained limited, and the life expectancy of patients with GBM has only been extended to ~15 months. Currently, genetically modified oncolytic viruses (OV) that express immunomodulatory transgenes constitute a research hot spot in the field of glioma treatment. An oncolytic virus is designed to selectively target, infect, and replicate in tumor cells while sparing normal tissues. Moreover, many studies have shown therapeutic advantages, and recent clinical trials have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of their usage. However, the therapeutic efficacy of oncolytic viruses alone is limited, while oncolytic viruses expressing immunomodulatory transgenes are more potent inducers of immunity and enhance immune cell-mediated antitumor immune responses in GBM. An increasing number of basic studies on oncolytic viruses encoding immunomodulatory transgene therapy for malignant gliomas have yielded beneficial outcomes. Oncolytic viruses that are armed with immunomodulatory transgenes remain promising as a therapy against malignant gliomas and will undoubtedly provide new insights into possible clinical uses or strategies. In this review, we summarize the research advances related to oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes, as well as potential treatment pitfalls in patients with malignant gliomas.

Subject terms: Cancer immunotherapy, CNS cancer

Facts

Oncolytic virus-encoded immunomodulatory transgene therapy for gliomas has yielded beneficial outcomes.

Oncolytic virus and tumor-targeting immune modulatory therapies have shown synergistic inhibition of malignant gliomas.

Oncolytic virus immunotherapy of malignant gliomas has been used in clinical trials.

The combination of stem cell carriers with oncolytic virus therapy for gliomas enhances antitumor efficacy.

Open questions

Can the immune system attack and engulf exogenous viruses?

Are glioma stem cells resistant to viral therapy?

Can the presence of nontumor cells such as tumor stroma cells impede the spread of oncolytic viruses?

In personalized medicine, should potential challenges be considered for the treatment of patients with malignant gliomas?

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is both the most aggressive and lethal malignant brain tumor in adults and accounts for more than 30% of intracranial tumors1,2. Current standard treatment options for malignant gliomas are multimodal and include surgical resection, postoperative radiotherapy, and concomitant chemotherapy with temozolomide1,3,4. Due to the invasive growth and recurrence features of malignant gliomas, the prognosis for patients with malignant gliomas remains extremely poor, with a median survival of nearly 15 months for newly diagnosed patients5,6. Thus, more specific, safe, and efficient treatment strategies are required. A growing body of preclinical and clinical data suggest that genetically engineered oncolytic viruses may be effective therapeutic agents used in the treatment of malignant gliomas.

Oncolytic virus (OV) therapy is a novel and promising therapeutic approach for tumors that involves selectively infecting and killing tumor cells. Prior research studies demonstrated that αvβ3 integrin and nectin-1 are required for efficient infection of cells by herpesvirus and adenovirus, respectively7,8, and the underlying mechanism may involve OV-induced cell destruction by cancer-specific genetic alteration, as well as sequential virus release and viral infection. It was first reported that tumors could be inhibited or shrunk in patients with cervical cancer and rabies virus positivity9. Researchers found that a conditionally and genetically modified replication-competent oncolytic virus was selectively toxic to tumor cells and nontoxic to normal cells10–12. Cassel et al. reported that a genetically engineered oncolytic virus was evaluated as an adjunctive therapeutic agent for patients with malignant melanoma13. Subsequently, oncolytic viruses, including G207 and HSV1716, were used for clinical research in patients with malignant gliomas in the USA and the UK14. In 2015, the FDA approved the use of an oncolytic virus in the USA to treat patients with melanoma15. In addition, recent advances in viral therapy, of which the most promising are perhaps viruses such as DNX-2401, PVS-RIPO, and Toca 511, have shown complete durable responses in ~20% of GBM patients who received virus intratumorally16–18. However, the clinical trial did not meet its primary endpoints. These encouraging results obtained with PVS-RIPO, Toca 511, and DNX-2401 have been granted a fast track designation by the FDA for expedited drug review processes.

Our research team previously found that the Endo–Angio fusion gene that is expressed in glioma stem cells (GSCs) could be administered via infection by oncolytic HSV-1, which carries an exogenous Endo–Angio fusion gene19. Furthermore, Friedman et al. summarized the milestones of oncolytic viruses carrying exogenous genes for cancer treatment20. In 2014, we also demonstrated that in animal models of human GSCs, an oncolytic HSV-1 that encodes an endostatin–angiostatin fusion gene could greatly enhance antitumor efficacy compared to HSV-1 without the fusion gene by generating antitumor angiogenic activity21. Later, our research team found that viruses that express the suicide gene cytosine deaminase (CD) could significantly enhance antitumor efficacy and prolong the life expectancy of tumor-bearing animals by the subsequent conversion of nontoxic prodrugs into toxic prodrugs22,23. Our research team independently developed a novel oHSV-1 containing the CD therapeutic gene. Moreover, a clinical trial using an engineered oHSV-1 (ON-01) injected intratumorally into patients with recurrent or refractory intracranial malignant gliomas is currently ongoing at Beijing Tiantan Hospital (China Clinical Trials registration number: ChiCTR1900022570).

A preclinical study demonstrated that intratumoral administration of OVs could drive the development of systemic antitumor immunity and result in elimination of contralateral tumors24. Moreover, oncolytic virus-mediated destruction of the tumor tissues was closely related to robust stimulation of innate antiviral immune responses and adaptive antitumor T-cell responses25. To further augment the antitumor effects, certain research studies have transduced immunomodulatory therapeutic transgenes, such as IL-1526–28, IL-1229–32, IL-433,34, and TRAIL35,36, via oncolytic virus, which can effectively inhibit or kill tumor cells through the antitumor immune response. Therefore, oncolytic viruses that encode immunomodulatory transgenes are gradually becoming a research hot spot in the field of glioma treatment. The gene required for oncolytic virus growth is typically placed under the control of a tumor-specific promoter or enhancer. In 2019, Yan et al. constructed a novel recombinant oncolytic adenovirus that expresses IL-15 and under the control of the E2F-1 promoter; it was found that this novel adenovirus could selectively kill tumor cells and exhibit increased antitumor effects both in vitro and in vivo26. Moreover, oncolytic viruses that were armed with immunomodulatory transgenes have been evaluated in several preclinical and clinical trials for the treatment of malignant gliomas. Genetically engineered virotherapy for malignant gliomas has so far been proven safe and effective. Nevertheless, many innovative strategies are currently under development to improve intratumoral viral expansion and antitumor efficacy without compromising security. Overall, previous studies on genetically engineered virotherapy with immunomodulatory transgenes have resulted in breakthroughs regarding several difficulties, which may contribute toward new insights into future therapeutics for patients with malignant gliomas.

Research advancements

Oncolytic viruses are a distinct class of antitumor agents with a unique mechanism of action that selectively replicate and target tumor cells, including GBM cells, affecting the tumor while sparing normal tissues and generating beneficial outcomes in GBM patients. However, diverse factors restrict the effect of virus treatment alone. In recent years, previous studies have inserted immunomodulatory genes into the viral genome, enabling the virus to release immune factors and simultaneously kill tumor cells in a direct manner; further, the antitumor immunologic reaction has been optimized, which has become a new approach for antitumor therapy. Oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes have been evaluated in terms of efficacy and safety in several preclinical and clinical trials for the treatment of malignant gliomas. However, their therapeutic utility in GBM appears to be limited due to several challenges.

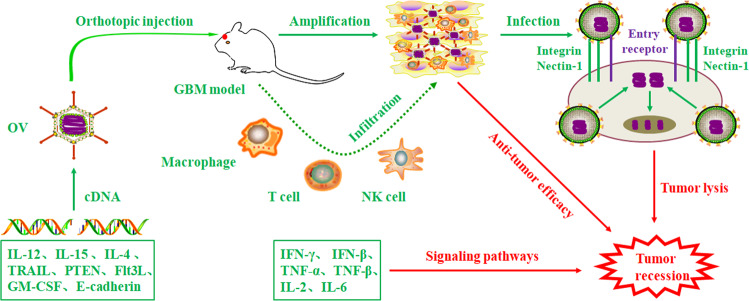

This review provides a summary of ongoing studies on engineered oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes for the treatment of malignant gliomas, as shown in Table 1. The therapeutic patterns of oncolytic viruses with immunomodulatory transgenes for glioblastoma treatment are particularly illuminated in Fig. 1. The oncolytic virus can be genetically engineered to express immune cytokines and to augment immune responses by enhancing immune cell infiltration and stimulating subsequent cascade immune networks. As such, these modified oncolytic viruses can be exploited and serve therapeutic advantages against gliomas.

Table 1.

A summary of currently open studies that utilize oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes against malignant gliomas.

| Immunomodulatory transgenes | Virus types | Delivery, Combination | Genetic alteration | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-15 | ADV | Intratumoral, CTL cells | E2F-1 promoter replaced E1A promoter | 27 |

| IL-12 | HSV | Intratumoral, anti-CTLA-4/PD-1 | Deletions of γ34.5 and α47, LacZ insertion | 29 |

| IL-4 |

HSV-1 HSV-1 |

Intratumoral, single agent Intratumoral, single agent |

Deletion of γ134.5, α27-tk insertion Deletion of γ134.5, α27-tk insertion |

30,33 |

| TRAIL | ADV | Subcutaneous, single agent | H5CmTERT promoter, Rb mutation | 36 |

| Anti-PD-1 | HSV-1 | Intratumoral, single agent | Deletions of γ34.5, LacZ insertion | 57 |

|

OX40L GM-CSF PTEN |

ADV VV ADV |

Intratumoral, anti-PD-L1 Subcutaneous, rapamycin Intratumoral, single agent |

Deletion of E1A gene, RGD-4C insertion LacZ insertion Deletions of El, E3 regions, and IX gene |

59,61,64 |

| P53 | ADV | Intratumoral, single agent | E1 deletion | 66 |

|

E-cad Flt3L |

HSV HSV-1 |

Intratumoral, single agent Intratumoral, single agent |

CDH1 gene insertion Deletions of γ134.5, LacZ insertion |

69,73 |

Fig. 1. Studies of oncolytic viruses expressing immunomodulatory transgene for GBM treatment.

Oncolytic viruses can be transduced to deliver antitumor agents, such as TRAIL, interleukins (IL-12, IL-4, and IL-15), immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1 antibody), immune-enhancing stimulators (OX40L and GM-CSF), tumor suppressors (PTEN and P53), E-cad and Flt3L, and are systemically administered to GBM sites. Afterward, OVs bind to certain receptors to infect and enter tumor cells, resulting in tumor lysis. OVs that are armed with immune factors can enhance antiglioma efficacy by recruiting immune cells, which include T cells, NK cells, and macrophages, to the GBM sites. These activated immune cells can secrete certain antitumor cytokines, including IFN-γ, IFN-β, TNF-α, TNF-β, IL-2, and IL-6, which ultimately induce tumor cell apoptosis by specific signaling pathways. In summary, OVs expressing immunomodulatory transgenes effectively lead to tumor recession by the combination of virotherapy and immunotherapy.

Oncolytic viruses that express IL-12

IL-12 is a heterodimeric protein that plays a pivotal role in linking the innate and adaptive immune systems. Previous data have demonstrated that IL-12 is a cytokine with potent antitumor properties. It is produced by antigen-presenting cells, including B lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and monocytes. It serves to augment the cytolytic activities of NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes and enables the development of a TH-1-type immune response30,37,38. In addition, the antiangiogenic properties of IL-12 have been identified and characterized39–41, which may represent a second potential mechanism for its antitumor activity. In recent years, researchers found that oncolytic viruses that express IL-12 could powerfully produce an antiglioma immune response in a glioma-bearing model29,31. Thus, the potential mechanisms of IL-12-mediated antitumor activity depend not only on the activation of the innate and adaptive effector immune systems but also on the inhibition of angiogenesis.

Based on the antitumor activity and antiangiogenic properties of IL-12, genes that express IL-12 have been inserted into the engineered oncolytic virus genome. In 2013, many studies reported that a genetically engineered oncolytic herpes simplex virus, when armed with the immunomodulatory cytokine interleukin 12, significantly enhanced the survival of tumor-bearing mice and effectively inhibited tumor growth42–46. Moreover, the safety and efficacy of the oncolytic virus were evaluated, and some strides were made in a clinical study. In 2017, Saha et al. found that the combination of an oncolytic HSV that expresses IL-12 with immune checkpoint inhibitors, including anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies, could potently eradicate glioma cells and extend the survival of glioma-bearing mouse models29. This combination provides new insight into glioma therapy. In brief, previous data and preclinical safety studies of another oncolytic HSV that expresses IL-12 also provide a compelling rationale for the clinical translation of IL-12-armed oncolytic HSVs for the treatment of patients with malignant gliomas.

Oncolytic viruses that express TRAIL

One novel strategy for tumor treatment is to induce apoptosis of tumor cells. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily and can induce apoptosis of tumor cells through activation of the TNF/CD95L axis and spare the majority of nonmalignant cells47. TRAIL is a strong therapeutic candidate for the treatment of glioblastoma because TRAIL can potently induce tumor-specific apoptosis48. With a deeper understanding of glioma therapy, TRAIL is widely used to exploit new therapeutic strategies. Most recent data have shown more potent antitumor efficacy of oncolytic viruses that encode TRAIL than of oncolytic viruses without TRAIL expression in xenograft models of subcutaneous and orthotopic glioblastoma, specifically through superior induction of apoptosis and the promotion of extensive viral distribution in tumor tissues35,36,49. Based on the properties of TRAIL-induced apoptosis of tumor cells, oncolytic viruses that express TRAIL could provide interesting approaches for glioma treatment.

Oncolytic viruses that express IL-15

IL-15, which is a part of the 4a-helix bundle cytokine family, is a crucial factor in immune regulation and primarily comes into play through the activation of NK cells. It is a receptor complex that consists of three subunits: a unique a-chain, a b-chain (shared with IL-2), and a common g-chain. As a novel molecular agent, IL-15 is used in tumor research and shows powerful antitumor immune responses through the stimulation of natural killer cells50–52. In 2017, Rivera et al. found that IL-15 could decrease the migration, invasion, and proliferation of tumor cells and inhibit angiogenesis53. Moreover, oncolytic viruses that express IL-15 significantly lyse tumor cells and reduce the tumor volume by activating natural killer (NK) cells, CD8+ T cells, and other immune cells27,28,54. Furthermore, our research team found that the destruction capacity of oncolytic adenovirus armed with IL-15 on tumor cells was stronger than that of the control virus (data not shown). Thus, the above evidence indicates that oncolytic virus-encoded IL-15 generates antitumor efficacy by activating innate and adaptive effector immune mechanisms, as well as by inhibiting angiogenic activity. This opens a new therapeutic direction for patients with malignant gliomas. However, due to limited research on oncolytic viruses encoding IL-15 for glioma treatment, further studies are necessary.

Oncolytic viruses that express immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoints, especially PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4, are immunosuppressive molecules that are upregulated in the GBM microenvironment29. Immune checkpoint blockers can regulate different inhibitory pathways on immune cells, overcome the immunosuppressive microenvironment, and further promote antitumor immunity through distinct and nonredundant immune evasion mechanisms55. Previous studies have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy with immune checkpoint inhibitors in orthotopic glioma-bearing models29. Moreover, Lukas et al. demonstrated the safety and efficacy of an immune checkpoint blocker (anti-PD-L1 antibody) in patients with recurrent GBM in a clinical trial56. In recent research, Passaro et al. confirmed that oHSV-1 encoding an anti-PD-1 antibody showed potent and durable antitumor immune responses after intratumoral administration and improved survival in preclinical GBM models57. Thus, OVs armed with immune checkpoint inhibitors may be a promising strategy for GBM patients in the future.

Oncolytic viruses that express immune stimulators

OX40 ligand (OX40L) is an immune costimulator that binds the unique costimulator OX40 on T cells58, which makes it a good option for OV therapy to increase activation of T cells, which further recognize antigens on tumor cells infected with the virus. Its mechanism is due to tumor-specific immunity, and this modality is more tumor-specific than immune checkpoint blockade. Previously, an oncolytic adenovirus expressing the immune costimulator OX40L exhibited superior tumor-specific activation of lymphocytes and proliferation of CD8+ T cells specific to tumor-associated antigens, resulting in cancer-specific immunity59. In addition, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is also a potent inducer of tumor-specific, long-lasting antitumor immunity in both animal models and human clinical trials9. Prior work demonstrated that oncolytic viruses expressing GM-CSF produced stronger antitumor immune responses in human solid tumors than oncolytic viruses not expressing GM-CSF60. Recent studies have investigated the efficacy and safety of oncolytic viruses encoding GM-CSF and their potentially enhanced immune activity in glioma-bearing models61,62. This tumor-specific strategy will be beneficial and efficacious for glioma patients in the future.

Oncolytic viruses that express tumor suppressors

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is recognized as a candidate tumor suppressor gene based on the presence of inactivating mutations in several tumors63. Given its deletion and mutation in tumors, some studies have transfected the PTEN gene into glioma cells, and the expression of exogenous PTEN impeded the growth of glioma via augmentation of the immune response. Previous research revealed that recombinant adenovirus armed with the PTEN gene was able to inhibit the proliferation and tumorigenicity of glioma cells64. In addition, P53 is also a tumor suppressor gene involved in several aspects of cell cycle control and suppression of transformation. P53-armed virus significantly decreased tumor volume and prolonged the survival of mice compared with control virus in GBM models65,66. A recombinant adenovirus expressing p53 in glioma cells led to biological effects of the newly expressed p53 protein, which induced apoptosis to produce rapid and generalized death of human glioma cells67. Therefore, using recombinant viruses for the delivery of tumor suppressor genes into glioma cells is a promising, rational, and effective approach to treat glioma based on the transfer of genes.

Oncolytic viruses that express E-cadherin

E-cadherin (E-cad) is a calcium-dependent cell–cell adhesion molecule that cooperates with nectin-1 in the formation of cell–cell adherent junctions. E-cad binding to the receptor KLRG1 protects E-cad-expressing cells from being lysed by NK cells. Overexpression of E-cad on virus-infected cells may directly facilitate cell-to-cell infection, which is the dominant method of intratumoral viral spread68. Recent studies have shown that oncolytic herpes viruses expressing E-cadherin inhibit the clearance of NK cells to enhance viral spread and cause tumor regression, and oHSVs encoding E-cad remarkably prolongs the survival rate in GBM-bearing mouse models69. This suggests that E-cad can be added as a module to oncolytic viruses to improve therapeutic efficacy in GBM.

Oncolytic viruses that express Flt3L

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) stimulates maturation and proliferation of DCs and NK cells. Flt3L protein could retard tumor progression and decrease the number of tumor metastases70. In 2006, Curtin et al. investigated an adenoviral vector expressing Flt3L (AdFlt3L) that induced a specific increase in the levels of IFN-α secreted by DCs in the brain71. Moreover, AdFlt3L prominently suppressed glioma growth and improved survival when tumors were treated within 3 days of implantation in an intracranial glioma model by creating an inflammatory environment72. In addition, Barnard et al. found that oHSVs expressing Flt3L significantly extended life expectancy in glioma-bearing mice73. This is a novel approach in which virus-mediated expression of Flt3L leads to either eradication of the tumor or significant extension of the life span of animals.

Potential pitfalls

Although oncolytic viruses that are armed with immunomodulatory transgenes for malignant glioma treatment have become increasingly popular, all oncolytic virus-based therapies, like other therapies, appear to be limited in their effectiveness. For example, the host responds to the oncolytic virus by inducing intratumoral infiltration of macrophages that can engulf the virus, limiting the potential of this therapeutic strategy. Some previous studies on the therapeutic effects of oncolytic viruses encoding immunomodulatory transgenes for malignant glioma treatment revealed potential pitfalls.

Tumor microenvironment

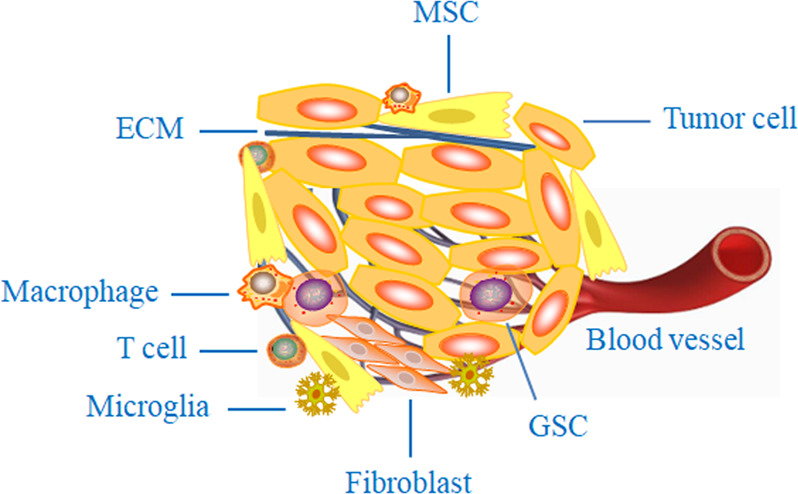

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is increasingly recognized as an important determinant of tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. A thorough understanding of the properties and functions of the TME is required to obtain a complete understanding of brain tumor biology and treatment. Generally, the tumor microenvironment consists of tumor cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, tumor stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), the extracellular matrix, and microglia, as well as cytokines and chemokines that are secreted by tumor and stromal cells74–78, as shown in Fig. 2. Previous work has shown that the TME can be improved and remodeled by external agents and factors, including spleen tyrosine kinase, salidroside, microvesicles, exosomes, and irradiation79–83. Over many decades, research groups have shown that oncolytic viruses can modulate changes in the TME and further generate antitumor immunity84–87. However, the regulatory mechanism of oncolytic viruses remains unclear, and adverse consequences of TME alteration have been gradually explored and reported.

Fig. 2. Diagram of the tumor microenvironment.

The composition of the TME is extremely complex, mainly consisting of tumor cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, GSCs, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), TAMs, the extracellular matrix (ECM), and microglia, as well as cytokines and chemokines. The TME is recognized as an important determinant of tumor progression and therapeutic resistance.

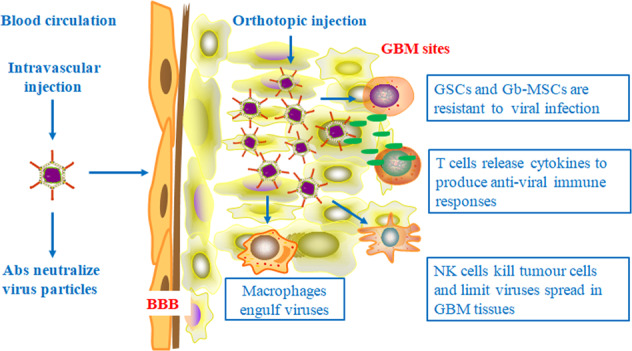

It is also important to seek understanding of how oncolytic viruses are affected by the TME in terms of differences between the TME and the natural milieu of the viruses. With a further understanding of the TME, researchers have demonstrated that immune infiltrating cells in the GBM microenvironment not only attack exogenous viruses but also restrict their spread to tumor cells and surrounding sites88–92, which may be a pitfall of immunomodulatory therapy, as shown in Fig. 3. TAMs are one of the major components in the TME. Although the shift from the protumor M2 (TAM2) to the antitumor M1 (TAM1) phenotype can obviously augment antiglioma effects93,94, macrophages can engulf and eliminate virus particles, which results in a significant reduction in virus titer in tumor sites. Recent studies have demonstrated that TAMs and microglia can limit the replication and spread of oncolytic viruses88,89. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are known to act as major immunosuppressive cells within the GBM microenvironment. MDSCs induce B cell-mediated immunosuppression, perhaps inhibiting the effective response to oncolytic viruses armed with immunomodulatory transgenes95. In addition, the blood–brain barrier (BBB) limits the delivery of viral vectors, greatly compromising their oncolytic efficacy25. Moreover, related investigations have shown that GSCs and glioma-associated mesenchymal stem cells (Gb-MSCs) in the TME are likely to generate resistance to oncolytic virus therapy78,87,96. Therefore, the number of effective viruses that arrive at the targeted sites will be greatly reduced. In 2017, Pulluri et al. reported that TME changes could generate resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic melanoma97, which indicates the possibility of cytotoxic properties in the glioma microenvironment. Last, these data raise controversial issues regarding the association between the TME and oncolytic viruses in terms of benefits or harm for efficacy. Thus far, there has not been a conclusive finding98. The previously mentioned pitfalls must be seriously considered, and potential mechanisms need to be further exploited. These data strongly suggest that the tumor microenvironment does pose potential safety hazards in terms of oncolytic virotherapy for malignant gliomas.

Fig. 3. Schematic summarizing the events and factors that are related to the limited effectiveness and spread of oncolytic viruses in GBM treatment.

Oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes are administered to the host by systemic vascular delivery or orthotopic injection. Systemic injection of OVs can be neutralized by Abs and blocked by the blood–brain barrier, and the OVs administered by orthotopic injection are engulfed and destroyed by activated immune cells, limiting viral spread in GBM tissues. In addition, GSCs and Gb-MSCs in the tumor microenvironment may be resistant to viral infection, which decreases therapeutic efficacy.

Do oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes support or suppress tumor angiogenesis?

Angiogenesis, the process by which new blood vessels develop from the preexisting vascular endothelium, plays a crucial role in solid tumor recurrence and progression. Hence, antitumor vascular therapy has also become a popular approach for malignant gliomas. However, it is worth mentioning that there is no definite conclusion on whether oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes support or suppress tumor angiogenesis. These confusing issues are interesting for researchers and the basis of several promising studies. In 2012, Sahin et al. found that oncolytic viral therapy with the oncolytic virus HF10 contributed to tumor angiogenesis and thus supported tumor growth; further, this may possibly have been due to the inflammatory response that was induced by viral infection and viral proteins that were expressed during viral replication99. The mechanisms that underlie enhanced angiogenesis are not precisely known, but preclinical data regarding herpetic stromal keratitis in wild-type HSV-1 infection revealed that angiogenesis may be induced by paracrine effects that result from the release of VP22 or CpG motifs in the HSV-1 DNA, which are required for viral replication100,101. However, previous studies demonstrated that oncolytic viruses could disrupt tumor vascular endothelial cells and inhibit angiogenesis by directly infecting and killing vascular endothelial cells102–104. Moreover, our research team found that the tube segment lengths of HUVECs treated with oncolytic adenovirus were significantly shorter than those of the controls. The potential mechanism may involve the oncolytic virus inhibiting tumor angiogenesis by targeting VEGF104. In addition, researchers have also reported that TRAIL significantly enhanced the angiogenic activity and migration ability of human microvascular endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo105,106. Additional data suggest that TRAIL primarily inhibits angiogenesis by inducing vascular endothelial apoptosis, which leads to vessel recession107–110. Moreover, IL-15 and IL-12 could significantly decrease the number of blood vessels, which generates antiangiogenic effects39–41,53. Nevertheless, there is apparently no definitive conclusion for whether oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes support or suppress tumor angiogenesis.

To avoid further confusion, these pitfalls must be thoroughly studied and resolved. With potential breakthroughs, a new era will begin for patients with malignant gliomas. Oncolytic virus-encoded immune cytokines have shown different abilities to promote or suppress tumor angiogenesis under different conditions. If these oncolytic viruses expressing immunomodulatory transgenes were investigated as glioma treatments, the effects of their support or suppression of the angiogenic potential of gliomas should also be considered.

The immune system combats exogenous viruses

Genetically engineered oncolytic viruses that are injected into the host can stimulate the immune system, generating a dual curative effect, which includes virus treatment and gene therapy. Research has shown that immune regulatory factors, including IL-4, IL-15, and IL-12, can enhance the activity of macrophages and neutrophils, contribute to the production and activation of natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells, and regulate cytokine production and memory T-cell survival and proliferation29,33,54. Thus, these complex elements could largely induce the apoptosis and lysis of tumor cells. Despite generating antitumor effects, the immune system also attacks the virus, which results in limited potency and expansion. This may explain why viruses cannot reach and kill distant tumors effectively.

Previous studies revealed that intravascularly injected viruses could be neutralized and eliminated by antibodies in the host111–113, as shown in Fig. 3. To overcome these hurdles, researchers have used careful orthotopic injection for malignant gliomas. However, activated macrophages and microglia engulf virus particles and limit their spread25,88,89. In 2015, Kober et al. found that microglia and astrocytes that were recruited in the TME preferentially cleared viral particles by immediate uptake after delivery, thus not allowing efficient viral infection114. As such, the efficacy and safety of genetically engineered oncolytic viruses must be guaranteed before wide application in clinical practice.

Tumor heterogeneity

Tumor heterogeneity is one of the most common characteristics of malignant tumors that contributes to tumor progression and recurrence115. Data from multiple studies demonstrate that higher levels of intratumoral heterogeneity predispose patients to inferior responses to anticancer therapies116. Heterogeneity provides a novel understanding of therapeutic resistance; thus, an accurate assessment of tumor heterogeneity is necessary to develop effective therapies.

It is well known that intertumoral and intratumoral heterogeneity persist in GBM, which is complicated due to the diverse tumor cell origins that are shown in glioma-bearing models and clinical tumor specimens117. Previous studies using single-cell analysis have identified the great heterogeneity in different GBM subtypes and emphasized the clinical significance of GBM heterogeneity118,119. The TME and location of the tumor can influence intratumoral heterogeneity, while different molecular subtypes, such as the proneural and classical mesenchymal subtypes, influence intertumoral heterogeneity. In 2014, Reardon et al. revealed that tumor heterogeneity significantly influenced the outcomes of patients with glioblastoma115. Tumor heterogeneity makes tumors highly resistant to different therapeutic strategies, which results in decreased efficacy116,120–122. One possible mechanism of resistance involves the heterogeneous expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in GBM123. This poses a substantial challenge for the effective use of EGFR-targeted therapies. In addition, our research team has repeatedly found that the sensitivity of different glioma cell lines to genetically engineered oncolytic adenoviruses is discrepant in research (data not shown), which suggests powerful treatment challenges for patients with malignant gliomas. Therefore, designing targeted therapies based on a range of molecular profiles can be a more effective strategy for eradicating treatment resistance, recurrence, and metastasis. Despite harvesting remarkable results in clinical trials, the therapeutic effects of oncolytic viruses on different types of malignant gliomas may be incredibly diverse. These data provide researchers with different insights into clinical treatment. Thus, a better understanding of glioblastoma heterogeneity is crucial for promoting therapeutic efficacy.

Future perspectives

Oncolytic virotherapy is a promising approach in which viruses are genetically modified to selectively replicate in tumor cells. Furthermore, the efficiency and safety of these viruses have been demonstrated in preclinical and clinical studies. Due to the previously mentioned obstacles, the spread and concentration of oncolytic viruses in the TME are restricted. To overcome such obstacles, a better understanding of the TME and better designed strategies for improved therapeutic efficacy should be pursued in research on oncolytic viruses for malignant glioma treatment. Oncolytic viruses encoding immunomodulatory transgene therapy for malignant gliomas may become a popular approach that is widely used for clinical practice in the future. Furthermore, the immune checkpoint molecule known as PD-1 has become a research hot spot in tumor research. For cancers with an immunologically ‘cold’ TME (e.g., GBM), immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy alone has not yet been successful124–127. However, one related study verified that the effect of oncolytic virus immunotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 antibody in glioblastoma was significantly better than that of oncolytic virus immunotherapy alone29,125. Thus, this combination should be translated to the clinic and tested against other immunosuppressive cancers.

The current approach for oncolytic virus administration mainly includes direct intratumoral injections and systemic vascular delivery. Stereotactic injections or resection bed inoculation are the most commonly studied and simplest methods for introducing viral vectors into high-grade gliomas. This approach has the advantage of bypassing the BBB and introduces a high concentration of viruses directly into the tumor tissues. However, it is limited by multiple factors in the host and only delivers a single dose. Currently, stem cell-based therapy for gliomas has emerged as a promising novel strategy. Given their inherent tumor-tropic migratory properties, stem cells can serve as vehicles for the delivery of therapeutic efficacy128. In 2008, Sonabend et al. reported that administration in MSCs enabled oncolytic virus delivery to distant glioma cells and that this delivery significantly enhanced the infection and apoptosis of tumor cells compared to injection alone, revealing a therapeutic advantage129. Moreover, in prior investigations, MSCs carrying oncolytic viruses were injected into the carotid artery of mice, and these cells migrated to tumor sites, which resulted in inhibited glioma growth and improved survival of glioma-bearing animals130–132. Since then, many studies using neural stem cells loaded with oncolytic adenoviruses have demonstrated extended delivery of the oncolytic virus and prolonged survival of glioma-bearing animals that were treated with the stem cell-mediated oncolytic virotherapy133–135. The given data reveal that stem cell vectors could improve the outcomes of oncolytic virotherapy for glioma treatment. With ongoing exploration of trans-differentiation techniques, the barrier of sourcing could be overcome. The advantages of combining stem cell vehicles with oncolytic virus-encoding immunomodulatory transgene therapy for patients with malignant gliomas may be a greater area of focus in the next few decades.

Conclusions

Genetically engineered oncolytic virus therapy for malignant gliomas has recently been an increasing focus of research. Oncolytic viruses that express immunomodulatory transgenes generate antitumor effects via oncolytic and immunotherapy effects. Despite the numerous oncolytic virus-related studies that have produced great strides in the field of glioma treatment, serious obstacles remain. Moreover, side effects that are caused by virotherapy in clinical trials exist. It remains uncertain whether oncolytic viruses, once appropriately modified, can be used to treat different types of gliomas. These issues need to be further explored and explained in future studies. In conclusion, using oncolytic viruses that are armed with immunomodulatory transgenes for malignant glioma treatment is still in its early stages, and a better understanding of the biological consequences of this therapy is required before its wide use in treating patients with malignant gliomas.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 8167100153) that was granted to Fu-sheng Liu.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by T. Kaufmann

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Qing Zhang, Email: qingm_zhang@hotmail.com.

Fusheng Liu, Email: liufusheng@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhang Q, et al. Current status and potential challenges of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for malignant gliomas. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:228. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0977-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matteoni S, et al. The influence of patient sex on clinical approaches to malignant glioma. Cancer Lett. 2020;468:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahangiri A, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery in glioblastoma: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. J. Neurosurg. 2017;126:191–200. doi: 10.3171/2016.1.JNS151591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stupp R, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballman KV, et al. The relationship between six-month progression-free survival and 12-month overall survival end points for phase II trials in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:29–38. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansouri A, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status testing to guide therapy for glioblastoma: refining the approach based on emerging evidence and current challenges. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21:167–178. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nestic, D. et al. αvβ3 integrin is required for efficient infection of epithelial cells with human adenovirus type 26. J. Virol.93, e01474-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Wirtz, L., Mockel, M. & Knebel-Morsdorf, D. Invasion of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 into murine dermis: the role of nectin-1 and herpesvirus entry mediator as cellular receptors during aging. J. Virol.94, e02046-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Fukuhara H, Ino Y, Todo T. Oncolytic virus therapy: a new era of cancer treatment at dawn. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1373–1379. doi: 10.1111/cas.13027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aghi M, Chou TC, Suling K, Breakefield XO, Chiocca EA. Multimodal cancer treatment mediated by a replicating oncolytic virus that delivers the oxazaphosphorine/rat cytochrome P450 2B1 and ganciclovir/herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene therapies. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3861–3865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda K, et al. Oncolytic virus therapy of multiple tumors in the brain requires suppression of innate and elicited antiviral responses. Nat. Med. 1999;5:881–887. doi: 10.1038/11320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haseley A, Alvarez-Breckenridge C, Chaudhury AR, Kaur B. Advances in oncolytic virus therapy for glioma. Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 2009;4:1–13. doi: 10.2174/157488909787002573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassel WA, Murray DR. A ten-year follow-up on stage II malignant melanoma patients treated postsurgically with Newcastle disease virus oncolysate. Med Oncol. Tumor Pharmacother. 1992;9:169–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02987752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foreman PM, Friedman GK, Cassady KA, Markert JM. Oncolytic virotherapy for the treatment of malignant glioma. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:333–344. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0516-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andtbacka RH, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:2780–2788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloughesy TF, et al. Durable complete responses in some recurrent high-grade glioma patients treated with Toca 511 + Toca FC. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:1383–1392. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desjardins A, et al. Recurrent glioblastoma treated with recombinant poliovirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:150–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang FF, et al. Phase I study of DNX-2401 (Delta-24-RGD) oncolytic adenovirus: replication and immunotherapeutic effects in recurrent malignant glioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:1419–1427. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.8219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu G, et al. Glioma stem cells targeted by oncolytic virus carrying endostatin-angiostatin fusion gene and the expression of its exogenous gene in vitro. Brain Res. 2011;1390:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman GK, Cassady KA, Beierle EA, Markert JM, Gillespie GY. Targeting pediatric cancer stem cells with oncolytic virotherapy. Pediatr. Res. 2012;71:500–510. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang G, et al. Enhanced antitumor efficacy of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus expressing an endostatin-angiostatin fusion gene in human glioblastoma stem cell xenografts. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan, W. et al. A hybrid nanovector of suicide gene engineered lentivirus coated with bioreducible polyaminoglycosides for enhancing therapeutic efficacy against glioma. Adv. Funct. Mater.29, 1–12 (2019).

- 23.Liu S, Song W, Liu F, Zhang J, Zhu S. Antitumor efficacy of VP22-CD/5-FC suicide gene system mediated by lentivirus in a murine uveal melanoma model. Exp. Eye Res. 2018;172:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moesta AK, et al. Local delivery of oncoVEX(mGM-CSF) generates systemic antitumor immune responses enhanced by cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:6190–6202. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martikainen, M. & Essand, M. Virus-based immunotherapy of glioblastoma. Cancers11, 1–16 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Yan, Y. et al. Inhibition of breast cancer cells by targeting E2F-1 gene and expressing IL15 oncolytic adenovirus. Biosci. Rep.39, 1–10 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yan Y, et al. Combined therapy with CTL cells and oncolytic adenovirus expressing IL-15-induced enhanced antitumor activity. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:4535–4543. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenson KB, Barra NG, Davies E, Ashkar AA, Lichty BD. Expressing human interleukin-15 from oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus improves survival in a murine metastatic colon adenocarcinoma model through the enhancement of anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;19:238–246. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2011.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saha D, Martuza RL, Rabkin SD. Macrophage polarization contributes to glioblastoma eradication by combination immunovirotherapy and immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:253–267, e255. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel DM, et al. Design of a phase I clinical trial to evaluate M032, a genetically engineered HSV-1 expressing IL-12, in patients with recurrent/progressive glioblastoma multiforme, anaplastic astrocytoma, or gliosarcoma. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 2016;27:69–78. doi: 10.1089/humc.2016.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker JN, et al. Engineered herpes simplex virus expressing IL-12 in the treatment of experimental murine brain tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:2208–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040557897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellums EK, et al. Increased efficacy of an interleukin-12-secreting herpes simplex virus in a syngeneic intracranial murine glioma model. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:213–224. doi: 10.1215/S1152851705000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andreansky S, et al. Treatment of intracranial gliomas in immunocompetent mice using herpes simplex viruses that express murine interleukins. Gene Ther. 1998;5:121–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post DE, et al. Targeted cancer gene therapy using a hypoxia inducible factor dependent oncolytic adenovirus armed with interleukin-4. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6872–6881. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wohlfahrt ME, Beard BC, Lieber A, Kiem HP. A capsid-modified, conditionally replicating oncolytic adenovirus vector expressing TRAIL Leads to enhanced cancer cell killing in human glioblastoma models. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8783–8790. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh E, Hong J, Kwon OJ, Yun CO. A hypoxia- and telomerase-responsive oncolytic adenovirus expressing secretable trimeric TRAIL triggers tumour-specific apoptosis and promotes viral dispersion in TRAIL-resistant glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1420. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19300-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Etxeberria, I. et al. Intratumor adoptive transfer of IL-12 mRNA transiently engineered antitumor CD8(+) T cells. Cancer Cell36, 613–629 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Gao P, Ding Q, Wu Z, Jiang H, Fang Z. Therapeutic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells producing IL-12 in a mouse xenograft model of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2010;290:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S, et al. IL-12 suppresses the expression of ocular immunoinflammatory lesions by effects on angiogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;71:469–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morini M, et al. Prevention of angiogenesis by naked DNA IL-12 gene transfer: angioprevention by immunogene therapy. Gene Ther. 2004;11:284–291. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strasly M, et al. IL-12 inhibition of endothelial cell functions and angiogenesis depends on lymphocyte-endothelial cell cross-talk. J. Immunol. 2001;166:3890–3899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ning J, Wakimoto H, Rabkin SD. Immunovirotherapy for glioblastoma. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:175–176. doi: 10.4161/cc.27039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitley RJ, Markert JM. Viral therapy of glioblastoma multiforme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:11672–11673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310253110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheema TA, et al. Multifaceted oncolytic virus therapy for glioblastoma in an immunocompetent cancer stem cell model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12006–12011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307935110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang W, et al. Combination of oncolytic herpes simplex viruses armed with angiostatin and IL-12 enhances antitumor efficacy in human glioblastoma models. Neoplasia. 2013;15:591–599. doi: 10.1593/neo.13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Passer BJ, et al. Combination of vinblastine and oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector expressing IL-12 therapy increases antitumor and antiangiogenic effects in prostate cancer models. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:17–24. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2012.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang XJ, et al. TRAIL-engineered bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: TRAIL expression and cytotoxic effects on C6 glioma cells. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:729–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim CY, et al. Cancer gene therapy using a novel secretable trimeric TRAIL. Gene Ther. 2006;13:330–338. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Mao Q, Wang D, Zhang W, Xia H. A fiber chimeric CRAd vector Ad5/11-D24 double-armed with TRAIL and arresten for enhanced glioblastoma therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2012;23:589–596. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fehniger TA, Cooper MA, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: immunotherapy for cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:169–183. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi H, et al. Role of trans-cellular IL-15 presentation in the activation of NK cell-mediated killing, which leads to enhanced tumor immunosurveillance. Blood. 2005;105:721–727. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rohena-Rivera K, et al. IL-15 regulates migration, invasion, angiogenesis and genes associated with lipid metabolism and inflammation in prostate cancer. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kowalsky SJ, et al. Superagonist IL-15-armed oncolytic virus elicits potent antitumor immunity and therapy that are enhanced with PD-1 blockade. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:2476–2486. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curran MA, Montalvo W, Yagita H, Allison JP. PD-1 and CTLA-4 combination blockade expands infiltrating T cells and reduces regulatory T and myeloid cells within B16 melanoma tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4275–4280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915174107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lukas RV, et al. Clinical activity and safety of atezolizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2018;140:317–328. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-2955-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Passaro C, et al. Arming an oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 with a single-chain fragment variable antibody against PD-1 for experimental glioblastoma therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:290–299. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao S, Zhu Y, Chen L. Advances in targeting cell surface signalling molecules for immune modulation. Nat. Rev. Drug Disco. 2013;12:130–146. doi: 10.1038/nrd3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang H, et al. Oncolytic adenovirus and tumor-targeting immune modulatory therapy improve autologous cancer vaccination. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3894–3907. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lei N, et al. An oncolytic adenovirus expressing granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor shows improved specificity and efficacy for treating human solid tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:33–43. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lun X, et al. Efficacy and safety/toxicity study of recombinant vaccinia virus JX-594 in two immunocompetent animal models of glioma. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1927–1936. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herrlinger U, et al. Helper virus-free herpes simplex virus type 1 amplicon vectors for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-enhanced vaccination therapy for experimental glioma. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000;11:1429–1438. doi: 10.1089/10430340050057503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teng DH, et al. MMAC1/PTEN mutations in primary tumor specimens and tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5221–5225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheney IW, et al. Suppression of tumorigenicity of glioblastoma cells by adenovirus-mediated MMAC1/PTEN gene transfer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2331–2334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fan X, et al. Overexpression of p53 delivered using recombinant NDV induces apoptosis in glioma cells by regulating the apoptotic signaling pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018;15:4522–4530. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kock H, et al. Adenovirus-mediated p53 gene transfer suppresses growth of human glioblastoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Cancer. 1996;67:808–815. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960917)67:6<808::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gomez-Manzano C, et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of the p53 gene produces rapid and generalized death of human glioma cells via apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:694–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwartzkopff S, et al. Tumor-associated E-cadherin mutations affect binding to the killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 in humans. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1022–1029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu, B. et al. An oncolytic herpesvirus expressing E-cadherin improves survival in mouse models of glioblastoma. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 45–54 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Shaw, S. G., Maung, A. A., Steptoe, R. J., Thomson, A. W. & Vujanovic, N. L. Expansion of functional NK cells in multiple tissue compartments of mice treated with Flt3-ligand: implications for anti-cancer and anti-viral therapy. J. Immunol.161, 2817–2824 (1998). [PubMed]

- 71.Curtin JF, et al. Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand recruits plasmacytoid dendritic cells to the brain. J. Immunol. 2006;176:3566–3577. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ali S, et al. Inflammatory and anti-glioma effects of an adenovirus expressing human soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (hsFlt3L): treatment with hsFlt3L inhibits intracranial glioma progression. Mol. Ther. 2004;10:1071–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barnard, Z. et al. Expression of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand by oncolytic herpes simplex virus type I prolongs survival in mice bearing established syngeneic intracranial malignant glioma. Neurosurgery71, 741–748 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Duan J, et al. CD30 ligand deficiency accelerates glioma progression by promoting the formation of tumor immune microenvironment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019;71:350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gutmann DH. Microglia in the tumor microenvironment: taking their TOLL on glioma biology. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:171–173. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Q, et al. Tumor evolution of glioma-intrinsic gene expression subtypes associates with immunological changes in the microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:42–56, e46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xie T, et al. Glioma stem cells reconstruct similar immunoinflammatory microenvironment in different transplant sites and induce malignant transformation of tumor microenvironment cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019;145:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2786-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang Q, et al. CD90 determined two subpopulations of glioma-associated mesenchymal stem cells with different roles in tumour progression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1101. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1140-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mondal A, Kumari Singh D, Panda S, Shiras A. Extracellular vesicles as modulators of tumor microenvironment and disease progression in glioma. Front Oncol. 2017;7:144. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang Y, et al. Effects of salidroside on glioma formation and growth inhibition together with improvement of tumor microenvironment. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2013;25:520–526. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2013.10.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meng X, et al. DNA damage repair alterations modulate M2 polarization of microglia to remodel the tumor microenvironment via the p53-mediated MDK expression in glioma. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moncayo G, et al. SYK inhibition blocks proliferation and migration of glioma cells and modifies the tumor microenvironment. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:621–631. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhou W, Jiang Z, Li X, Xu Y, Shao Z. Cytokines: shifting the balance between glioma cells and tumor microenvironment after irradiation. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015;141:575–589. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1772-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qiao J, et al. Intratumoral oncolytic adenoviral treatment modulates the glioma microenvironment and facilitates systemic tumor-antigen-specific T cell therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1022302. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1022302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kurozumi K, et al. Effect of tumor microenvironment modulation on the efficacy of oncolytic virus therapy. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1768–1781. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Silva N, Atkins H, Kirn DH, Bell JC, Breitbach CJ. Double trouble for tumours: exploiting the tumour microenvironment to enhance anticancer effect of oncolytic viruses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hu Q, et al. Tumor microenvironment and angiogenic blood vessels dual-targeting for enhanced anti-glioma therapy. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:23568–23579. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b08239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fulci G, et al. Depletion of peripheral macrophages and brain microglia increases brain tumor titers of oncolytic viruses. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9398–9406. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Denton, N. L., Chen, C. Y., Scott, T. R. & Cripe, T. P. Tumor-associated macrophages in oncolytic virotherapy: friend or foe? Biomedicines4, 1–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Haseley A, et al. Extracellular matrix protein CCN1 limits oncolytic efficacy in glioma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1353–1362. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Choi IK, et al. Effect of decorin on overcoming the extracellular matrix barrier for oncolytic virotherapy. Gene Ther. 2010;17:190–201. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dmitrieva N, et al. Chondroitinase ABC I-mediated enhancement of oncolytic virus spread and antitumor efficacy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:1362–1372. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhao P, et al. Dual-targeting biomimetic delivery for anti-glioma activity via remodeling the tumor microenvironment and directing macrophage-mediated immunotherapy. Chem. Sci. 2018;9:2674–2689. doi: 10.1039/c7sc04853j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Levy A, et al. CD38 deficiency in the tumor microenvironment attenuates glioma progression and modulates features of tumor-associated microglia/macrophages. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:1037–1049. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee-Chang C, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressive cells promote B cell-mediated immunosuppression via transfer of PD-L1 in glioblastoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019;7:1928–1943. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Audia A, Conroy S, Glass R, Bhat KPL. The impact of the tumor microenvironment on the properties of glioma stem-like cells. Front Oncol. 2017;7:143. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pulluri B, Kumar A, Shaheen M, Jeter J, Sundararajan S. Tumor microenvironment changes leading to resistance of immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic melanoma and strategies to overcome resistance. Pharm. Res. 2017;123:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stanford MM, Breitbach CJ, Bell JC, McFadden G. Innate immunity, tumor microenvironment and oncolytic virus therapy: friends or foes? Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2008;10:32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sahin TT, et al. Impact of novel oncolytic virus HF10 on cellular components of the tumor microenviroment in patients with recurrent breast cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;19:229–237. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2011.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zheng M, Klinman DM, Gierynska M, Rouse BT. DNA containing CpG motifs induces angiogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8944–8949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132605599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Choudhary A, et al. Suppression of thrombospondin 1 and 2 production by herpes simplex virus 1 infection in cultured keratocytes. Mol. Vis. 2005;11:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yoo JY, et al. Antitumor efficacy of 34.5ENVE: a transcriptionally retargeted and “Vstat120”-expressing oncolytic virus. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:287–297. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Breitbach CJ, et al. Oncolytic vaccinia virus disrupts tumor-associated vasculature in humans. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1265–1275. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hou W, Chen H, Rojas J, Sampath P, Thorne SH. Oncolytic vaccinia virus demonstrates antiangiogenic effects mediated by targeting of VEGF. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;135:1238–1246. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cartland, S. P., Genner, S. W., Zahoor, A. & Kavurma, M. M. Comparative evaluation of TRAIL, FGF-2 and VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17, 1–11 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 106.Di Bartolo, B. A. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) promotes angiogenesis and ischemia-induced neovascularization via NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) and nitric oxide-dependent mechanisms. J. Am. Heart Assoc.4, 1–16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 107.Cantarella G, et al. TRAIL inhibits angiogenesis stimulated by VEGF expression in human glioblastoma cells. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;94:1428–1435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Na HJ, et al. TRAIL negatively regulates VEGF-induced angiogenesis via caspase-8-mediated enzymatic and non-enzymatic functions. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:179–194. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang Y, et al. Combined endostatin and TRAIL gene transfer suppresses human hepatocellular carcinoma growth and angiogenesis in nude mice. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009;8:466–473. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.5.7687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen PL, Easton AS. Evidence that tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) inhibits angiogenesis by inducing vascular endothelial cell apoptosis. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;391:936–941. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ilett EJ, et al. Internalization of oncolytic reovirus by human dendritic cell carriers protects the virus from neutralization. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:2767–2776. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jennings VA, et al. Lymphokine-activated killer and dendritic cell carriage enhances oncolytic reovirus therapy for ovarian cancer by overcoming antibody neutralization in ascites. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;134:1091–1101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mader EK, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell carriers protect oncolytic measles viruses from antibody neutralization in an orthotopic ovarian cancer therapy model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:7246–7255. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kober C, et al. Microglia and astrocytes attenuate the replication of the oncolytic vaccinia virus LIVP 1.1.1 in murine GL261 gliomas by acting as vaccinia virus traps. J. Transl. Med. 2015;13:216. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0586-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reardon DA, Wen PY. Glioma in 2014: unravelling tumour heterogeneity-implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12:69–70. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Parker NR, Khong P, Parkinson JF, Howell VM, Wheeler HR. Molecular heterogeneity in glioblastoma: potential clinical implications. Front Oncol. 2015;5:55. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Abdallah MG, et al. Glioblastoma Multiforme heterogeneity profiling with solid-state micropores. Biomed. Microdevices. 2019;21:79. doi: 10.1007/s10544-019-0416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Patel AP, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014;344:1396–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Akgul, S. et al. Intratumoural heterogeneity underlies distinct therapy responses and treatment resistance in glioblastoma. Cancers11, 1–17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 121.Ryu YJ, et al. Glioma: application of whole-tumor texture analysis of diffusion-weighted imaging for the evaluation of tumor heterogeneity. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Qazi MA, et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity: pathways to treatment resistance and relapse in human glioblastoma. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:1448–1456. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Furnari FB, Cloughesy TF, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. Heterogeneity of epidermal growth factor receptor signalling networks in glioblastoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:302–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Preusser M, Lim M, Hafler DA, Reardon DA, Sampson JH. Prospects of immune checkpoint modulators in the treatment of glioblastoma. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11:504–514. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Saha D, Martuza RL, Rabkin SD. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus immunovirotherapy in combination with immune checkpoint blockade to treat glioblastoma. Immunotherapy. 2018;10:779–786. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sharpe AH, Pauken KE. The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:153–167. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Corsten MF, Shah K. Therapeutic stem-cells for cancer treatment: hopes and hurdles in tactical warfare. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:376–384. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sonabend AM, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively deliver an oncolytic adenovirus to intracranial glioma. Stem Cells. 2008;26:831–841. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Josiah DT, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells as therapeutic delivery vehicles of an oncolytic virus for glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:377–385. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yong RL, et al. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for intravascular delivery of oncolytic adenovirus Delta24-RGD to human gliomas. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8932–8940. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Parker Kerrigan BC, Shimizu Y, Andreeff M, Lang FF. Mesenchymal stromal cells for the delivery of oncolytic viruses in gliomas. Cytotherapy. 2017;19:445–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ahmed AU, et al. Neural stem cell-based cell carriers enhance therapeutic efficacy of an oncolytic adenovirus in an orthotopic mouse model of human glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:1714–1726. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ahmed AU, et al. A preclinical evaluation of neural stem cell-based cell carrier for targeted antiglioma oncolytic virotherapy. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:968–977. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Morshed RA, et al. Analysis of glioblastoma tumor coverage by oncolytic virus-loaded neural stem cells using MRI-based tracking and histological reconstruction. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22:55–61. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2014.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]