Abstract

The aim of the study was to quantify sugar profile and rheological behaviour of four Indian honey varieties (Cotton, Coriander, Dalbergia, and Murraya). The effect of temperature (5, 10, 20 and 30 °C) on rheological behaviour of these honey varieties was also studied. Fourteen sugars (three monosaccharides, six disaccharides, four trisaccharides, and one oligosaccharide) were quantified. The concentration of glucose and fructose varied from 33.40–34.06% to 36.86–41.15%, respectively. Result indicated that monosaccharides were the dominant sugars among all the honey samples. Low amounts of turanose, trehalose, melibiose, and raffinose were present in the range of 0.02–0.03%, 0.11–0.26%, 0.09–0.18% and 0.06–0.12%, respectively in the analyzed honey varieties. The rheological behaviour of all four honey varieties was analysed at different temperatures i.e. 5, 10, 20 and 30 °C followed an Arrhenius model. In analysed honey varieties storage modulus (G′) was less than loss modulus (G″) which confirmed the Newtonian behaviour of all honey samples.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-020-04331-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Honey, Sugars, Rheology, Arrhenius model, Newtonian fluid

Introduction

Honey is a sweet liquid produced by the honeybees from honeydew or nectar, which contains more than 90% of the honey solids as carbohydrates (predominating fructose and glucose), enzymes, amino acids, vitamins, organic acids, polyphenols and minerals (Ouchemoukh et al. 2010; Primorac et al. 2011). Physico-chemical properties and composition of honey varied owing to geographical, seasonal, floral source, processing, packaging and storage conditions (Nayik and Nanda 2016). The properties such as hygroscopicity, granulation, viscosity and energy value of honey are due to presence of sugar in the honey (Ouchemoukh et al. 2010). The amount of glucose and fructose are useful to classify unifloral honey. Floral honey obsessed a low concentration of trisaccharides i.e. raffinose and melezitose, whereas this concentration was more in honeydew honey (Bentabol Manzanares et al. 2011). Oligosaccharides are available in honey possessed prebiotic activity which shows an increment in Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria (Sanz et al. 2005). Numerous researchers have reported the sugar profile of various honey varieties (De La Fuente et al. 2011; Nayik et al. 2016). Chromatographic techniques such as GC–MS (Lazaridou et al. 2004) or HPLC (Nayik et al. 2016) have been widely used for analysis of different types of sugar in honey. HPLC or GC is used to identify adulterations in honey, qualitative and quantitative analysis of saccharides (Cotte et al. 2003) and to distinguish it from nectar and honeydew honey (Persano Oddo and Piro 2004).

Rheological behaviour of honey is valuable in handling, intermediate processing, and storage of honey (Nayik et al. 2016). Rheological properties were affected by some factors including chemical composition and the size and quantity of crystals (Juszczak and Fortuna 2006). The honey undergoes a broad range of temperature change in storage and processing, hence, the effect of thermal treatment on the rheology of honey is required to explore (Nayik et al. 2016). Fructose to glucose (F/G) ratio is a characteristic for verification of crystallization rate, which influences the rheological behaviour of honey (Witczak et al. 2011). Most of the researchers reported Newtonian behaviour of honey (Juszczak and Fortuna 2006; Lazaridou et al. 2004; Zaitoun et al. 2001), whereas some varieties exhibited non-Newtonian flow behaviour could be because of existence of few dextran or proteins in the honey (Witczak et al. 2011). Rheological parameters like storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) have been calculated for some honey (Lazaridou et al. 2004; Nayik et al. 2016). Arrhenius, Herschel–Bulkley, and Power law models are helpful to explain the temperature dependence on the rheological behaviour of honey samples (Lazaridou et al. 2004). The rheological properties of various types of Chinese honey were observed by Junzheng and Changying (1998) and revealed that the Newtonian model effectively described a linear relationship among the shear rate and shear stress.

The genuineness of Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), Coriander (Coriandrum sativum), Indian rosewood (Dalbergia sissoo) and curry leaf (Murraya koenigii) honey was recognized by melissopalynology and physicochemical properties, flavonoids content, phenolic content, with trace minerals (Fe, Ni, Cu, Pb, Mn and Cd) of honey were studied (Kamboj et al. 2013a). However, still, the work on sugar profile by HPLC and rheology by Compact Rheometer on honey varieties from the plain region of India has never been investigated earlier. Authors inspired to characterize sugar profile and rheological properties of these four honey varieties. So the present study aimed to characterize four varieties of honey belongs to the plain region of India by sugar profile using HPLC and also by the influence of the change of temperature on the rheological behaviour of honey.

Materials and methods

Honey sample collection

Sixty seven samples of honey from four botanical origins (Murraya koenigii, Coriandrum sativum, Dalbergia sissoo, and Gossypium hirsutum) were collected between September 2009 to October 2013 directly from beekeepers from four main honey producing provinces in India Viz. Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, and Rajasthan. Samples were preserved in glass bottles and stored at a temperature of 4 °C. Melissopalynology confirmed the source of each honey samples and classified as per their floral source by the method depicted by Von der Ohe et al. (2004). The terms used for classification were: predominant pollen (> 45%), secondary pollen (16–45%), important minor pollen (3–15%) and minor pollen (< 3%).

Standards and chemicals for sugar analysis

Fructose, glucose, xylose, isomaltose, maltose, trehalose, turanose, melibiose, raffinose, erlose, sucrose, maltotriose, melezitose, maltotetraose, ultrapure water, and organic solvents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Mumbai, India).

Estimation of different sugars by HPLC: refractive index

All sugars were detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent 1120 Compact LC, USA), using Hi-plex pb, 300 mm × 7.7 mm, 8µ particle size column (Agilent, USA), Refractive Index detector (Agilent, USA) and Agilent EZChrom Elite software. The eluting solvent used was water.

To prepare mobile phase, acetonitrile and water were taken in the ratio of 80:20. Mobile phase was filtered and degassed through vacuum filtration (0.45 µm PTFE membrane filter). Stock solutions of all sugars (10 g/l each) were prepared. A flow rate of 0.6 ml/min was maintained for injection of standard solutions. When most favourable flow conditions achieved, standards were injected to get peak heights and elution times. These peaks were utilized to draw calibration graphs for sugars. 2.5 g of the honey samples were weighed in polypropylene tubes and 10 ml of 60% methanol was mixed. All samples were filtered and degassed through vacuum filtration (0.45 µm PTFE membrane filter). By using similar conditions samples were introduced, and calibration graphs were plotted to obtain the sugars of the honey samples.

Measurement of rheological properties

Samples were heated in the water bath at 50 °C for 1 h to dissolve the crystals of honey and then samples were kept at a temperature of 30 °C to eliminate air bubbles.

Dynamic shear rheological properties

Rheological behaviour of honey samples was evaluated by Modular Compact Rheometer (MCR 302, Anton Paar, Austria) having parallel plate system (50 mm diameter) with an opening of 0.5 mm at 5, 10, 20 and 30 °C. Frequency sweep in the range of 0.63–63 rad/s at 0.5% shear strain was used to find out rheological data. Power law (Eq. 1) was utilized to characterize the behaviour of fluids while it fits very well in the experimental data, as this model is simple and having broad technological applications.

| 1 |

where τ is shear stress (Pa), K is the consistency coefficient (Pa.sn), γ is the shear rate (s−1), and n is the flow behaviour index (dimensionless).

Magnitudes of intercepts (K′ and K″), slopes (n′ and n″) and coefficient of regression (R2) were calculated using the following equations:

| 2 |

| 3 |

where G′ is storage modulus, K′ and n′ is elastic intercept and slope, respectively, ω is angular frequency, G″ is loss modulus, K″ and n″ represent viscous intercept and slope, respectively.

Effect of temperature on rheological properties

Arrhenius model was applied to study the effect of a change in temperature on loss modulus (G″) and viscosity (η), which is as follows:

| 4 |

| 5 |

where Go and ηo values are the constants of G″ and η, respectively; Ea represents activation energy (kJ/mol), R is gas constant (8.314 kJ/mol/K) and T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin.

Statistical analysis

All readings were taken in duplicate and Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was employed to express means (P < 0.05) using Statistica version 7.0 software (StatSoft, Inc., USA).

Results and discussion

Sugar analysis

Fourteen types of sugars were quantified in the present study consisting of three monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, xylose), six disaccharides (maltose, isomaltose, turanose, trehalose, melibiose, sucrose), four trisaccharides (raffinose, erlose, maltotriose, melezitose) and one oligosaccharide (maltotetraose). HPLC chromatogram depicted the retention times as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a, b.

The values of the sugar content are shown in Table 1 and the total sugar content of all honey samples ranged from 79.89 to 85.65%. The obtained values were in agreement with the values depicted by various researchers in floral honey (Bentabol Manzanares et al. 2011; Nayik et al. 2016). Total monosaccharides in all the samples were in the range of 70.57–75.35% (Table 1) which was comparable to the values represented by Nayik et al. (2016). The results revealed that amount of monosaccharides (glucose and fructose) in all the honey samples authenticate the genuineness. Sugars are the major constituent of honey which are mainly based on geographical and floral source also influenced by processing, storage and climatic conditions (Dobre et al. 2012; Escuredo et al. 2014).

Table 1.

Sugar content of different Indian honey types

| Parameters | % of sugars | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton (n = 12) | Coriander (n = 23) | Dalbergia (n = 18) | Murraya (n = 14) | |

| Fructose | 36.98 ± 0.58b | 37.09 ± 0.47b | 41.15 ± 0.04a | 36.86 ± 0.10b |

| Glucose | 33.91 ± 0.19a | 33.94 ± 0.30a | 34.06 ± 1.04a | 33.40 ± 1.03a |

| Xylose | 0.31 ± 0.10a | 0.28 ± 0.03a | 0.14 ± 0.03b | 0.31 ± 0.07a |

| Sucrose | 3.54 ± 0.37a | 3.11 ± 0.24a | 3.41 ± 0.43a | 3.59 ± 0.38a |

| Maltose | 1.44 ± 0.21a | 1.56 ± 0.22a | 1.86 ± 0.13a | 1.54 ± 0.28a |

| Isomaltose | 1.66 ± 0.12b | 1.96 ± 0.17a | 1.54 ± 0.12b | 1.16 ± 0.13c |

| Turanose | 0.03 ± 0.02a | 0.02 ± 0.01a | 0.03 ± 0.01a | 0.03 ± 0.03a |

| Trehalose | 0.18 ± 0.07ab | 0.26 ± 0.08a | 0.16 ± 0.05ac | 0.11 ± 0.05bc |

| Melibiose | 0.09 ± 0.03bc | 0.12 ± 0.04ab | 0.18 ± .04a | 0.12 ± 0.04ac |

| Raffinose | 0.08 ± 0.03a | 0.09 ± 0. 03a | 0.12 ± 0.04a | 0.06 ± 0.02a |

| Erlose | 0.39 ± 0.16a | 0.54 ± 0.07a | 0.69 ± 0.19a | 0.45 ± 0.16a |

| Maltotriose | 1.18 ± 0.04ac | 1.29 ± 0.08a | 1.26 ± 0.07ab | 1.15 ± 0.06bc |

| Melezitose | 0.36 ± 0.05a | 0.39 ± 0.04a | 0.38 ± 0.04a | 0.26 ± 0.05b |

| Maltotetraose | 0.89 ± 0.07a | 0.66 ± 0.15b | 0.67 ± 0.05b | 0.85 ± 0.07a |

| Total monosac. (%) | 71.20 ± 0.28b | 71.31 ± 0.13b | 75.35 ± 0.31a | 70.57 ± 0.19c |

| Total disac. (%) | 6.94 ± 0.17a | 6.94 ± 0.36a | 7.18 ± 0.21b | 6.55 ± 0.09a |

| Total trisac. (%) | 2.01 ± 0.15a | 2.31 ± 0.18a | 2.45 ± 0.09a | 1.92 ± 0.23a |

| Total Sugars (%) | 81.04 ± 0.09b | 81.31 ± 0.21b | 85.65 ± 0.17a | 79.89 ± 0.25c |

| Total Reducing Sugars (%) | 75.60 ± 0.28b | 76.26 ± 0.28b | 80.22 ± 0.28a | 74.57 ± 0.28b |

| Total Non-reducing Sugars (%) | 5.44 ± 0.28a | 5.05 ± 0.28b | 5.43 ± 0.28a | 5.32 ± 0.28ab |

| F + G (%) | 70.89 | 71.03 | 75.21 | 70.26 |

| F/G ratio | 1.09 ± 0.08a | 1.09 ± 0.03a | 1.21 ± 0.12a | 1.10 ± 0.07a |

Results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviations. Means in a row with same superscripts (a, b, c, d) are not significantly different (P < 0.05)

Monosaccharides

The mean fructose content was maximum in Dalbergia honey (41.15%) followed by Coriander honey (37.09%), Cotton honey (36.98%) and Murraya honey (36.86%). Dalbergia honey was statistically different (P < 0.05) among all the honey sources. These results were comparable with the work of various investigators for Spanish and Indian unifloral honey (Nozal et al. 2005; De La Fuente et al. 2011; Nayik et al. 2016), but a higher range of fructose in acacia honey (41.3–43.30%) and black locust honey (39.70–49.10%) was reported by Primorac et al. (2011) and Escuredo et al. (2014), respectively. Mean concentration of fructose was 31.50% in Coriander honey from Iran (Khalafi et al. 2016) which was less than reported value. The concentration of fructose was in close comparison with the values reported by Senyuva et al. (2009) i.e. 37.80% fructose in Cotton honey from Turkey.

The glucose concentration of analyzed honey samples was found in the range of 33.40–34.06%, resulting in 3–6% lowers than the fructose content and the values coincided with the result revealed by Escuredo et al. (2014). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were studied in identified sugar between all honey types. Persano Oddo and Piro (2004) reported that European honey possessed glucose content in the range of 23.9–40.5% and these values were consistent with the present study. Moreover, work on a variety of Australian honey was done by Sopade et al. (2004), and they revealed that fructose and glucose content varied from 31.0% to 44.9% and 23.9% to 33.0%, respectively. Honey with more than 30% glucose content showed rapid crystallization which may be due to the lesser water solubility of glucose.

Combined level of glucose and fructose were present in the range of 70.26–75.21% (Table 1) by the highest range in Dalbergia and lowest range in Murraya honey. Values found under the present study were comparable for various honey varieties as revealed by various researchers (Bentabol Manzanares et al. 2011; Primorac et al. 2011; Escuredo et al. 2014; Nayik et al. 2016). While recorded values in the present study were more than the values reported by Senyuva et al. (2009) and Khalafi et al. (2016) in Coriander honey (60.60%) from Iran and in Cotton honey (67.30%) from Turkey, respectively.

Xylose is a rare reducing sugar available among honey. The xylose content found in Cotton, Coriander, Dalbergia and Murraya honey ranged between 0.14% and 0.31% which were comparable with results reported by Nayik et al. (2016) in various high altitude Indian honey. The reported values in the present study were lower than Croatians unifloral honey (0.10–0.70%) as revealed by Primorac et al. (2011). The reason possibly owing to various geographical and climatic conditions.

Disaccharides

The total disaccharide in all honey varieties varied from 6.55 to 7.18% as shown in Table 1, which was quite similar to values (2.70–8.57%) described by Ouchemoukh et al. (2010) in various Algerian honey. Coriander honey had lowest sucrose content (3.11%) whereas Murraya honey had highest (3.59%) these values were higher than the values reported by other workers (Rybak-Chmielewska et al. 2013; Nayik et al. 2016). All analyzed honey types contained sucrose content less than the prescribed limit, i.e. 5% (Codex Alimentarius 2001), which indicated that these honey were ripened. The concentration of sucrose varies with the degree of maturity and source of nectar (Kamboj et al. 2013b). The maltose percentage varied from 1.44% to 1.86% among the four varieties of honey and the results were consistent with Juszczak et al. (2009). Senyuva et al. (2009) reported low maltose content (< 0.6%) in Cotton honey from Turkey. In Spanish honey, a wide range of maltose 2.33–7.00% was reported by Bentabol Manzanares et al. (2011).

The isomaltose concentrations in honey samples under the present study were found in the range of 1.16–1.96% and Coriander honey is significantly (P < 0.05) different among all other varieties. These findings were consistent with the value represented by Nozal et al. (2005) and Bentabol Manzanares et al. (2011) for Spanish honey. Nayik et al. (2016), reported less amount (0.13–0.92%) whereas Rybak-Chmielewska et al. (2013) reported a higher value of this disaccharide in their study. Very low concentrations of turanose (0.02–0.03%) were observed in the present work. Results were in close comparison as reported by various other workers (Ouchemoukh et al. 2010; Bentabol Manzanares et al. 2011). Concentrations of trehalose were determined in the range of 0.11–0.26% in the present work and Coriander honey is significantly different (P < 0.05) from Murraya honey. Nozal et al. (2005) in French lavender, spike lavender, and thyme honey depicted similar results. Rybak-Chmielewska et al. (2013) found a high concentration of trehalose content (0.6–4.9%) in Polish honey. Melibiose content was found in the range of 0.09–0.18% (Table 1); Cotte et al. (2003) reported melibiose content of honey (Lavender, Acacia, and Chestnut) obtained from France as 0.05%, 0.14% and 0.30%, respectively.

Trisaccharides and oligosaccharide

The total trisaccharides concentration in different honey samples ranged between 1.92% and 2.45% is shown in Table 1, which was in agreement with Cotte et al. (2003). Raffinose varied in analyzed honey varieties from 0.06% to 0.12%. The concentration of raffinose in this study was comparable to 0.01–0.16% in Algerian honey (Ouchemoukh et al. 2010), 0.02–0.08% in Spanish honey (De La Fuente et al. 2011) and 0.04–0.10% in Indian honey (Nayik et al. 2016). Erlose varied from 0.39% to 0.69%, which was highest in Dalbergia honey and lowest in Cotton honey. These results were in agreement with the values revealed by other researchers (Nozal et al. 2005; Ouchemoukh et al. 2010).

The mean values of maltotriose varied from 1.15% to 1.29%. These observed values were slightly higher than those recorded by Nayik et al. (2016) in Indian honey. Melezitose was used as an indicator to differentiate between honeydew and floral honey (De La Fuente et al. 2011). The average concentration of melezitose was recorded from 0.26–0.39% in the four varieties of honey samples which coincided with the values described by Szczesna et al. (2011) for floral honey. The low melezitose content is an indication of blossom honey and the same results have been shown under the present study. Rybak-Chmielewska et al. (2013) reported the high value of melezitose (6.57%) in Spanish honeydew honey and (3.2%) in Polish honeydew honey samples described a specific marker for such honey. Dobre et al. (2012) also reported higher melezitose content in honeydew honey from Romania. In contrast, Escuredo et al. (2013) reported the low value of melezitose in honeydew honey. In the present study, the concentration of maltotetraose was quantified as 0.66–0.89% which was comparable with the values recorded by Nayik et al. (2016) for Indian honey.

Total reducing sugars were in the range of 74.57–80.22%. These values were higher than those reported by Nayik et al. (2016). In present investigation, the highest concentration of total reducing sugars was detected in Dalbergia honey followed by Coriander, Cotton and Murraya honey. Total non-reducing sugars were quantified in the range of 5.05–5.44%, which were found in higher concentration in Cotton honey and lowest in Coriander honey. These results were consistent with Hedysarum honey from Algeria (Ouchemoukh et al. 2010).

Crystallization ratio

The ratio of fructose to glucose (F/G) was utilized to discriminate between honeydew and floral honey (Dobre et al. 2012). F/G ratio is also considerable parameter used to predict crystallization potential of honey (Laos et al. 2011). In the present study various honey viz. Coriander, Cotton, Murraya and Dalbergia had F/G ratio as 1.09, 1.09, 1.10 and 1.21, respectively, which were in close agreement with the values reported by different scientists (Nozal et al. 2005; Primorac et al. 2011; Szczesna et al. 2011). F/G ratio reported in lime, rape, and sunflower honey was found as 1.17, 1.13 and 1.02, respectively (Escuredo et al. 2014) and these values coincide with the present findings. F/G ratio of Dalbergia (1.21) was similar as found in most of the honey samples reported by various investigators (Cotte et al. 2003; Bentabol Manzanares et al. 2011; Dobre et al. 2012). F/G ratio of 1.14 or less would be a sign of faster crystallization. Consequently, three varieties (Cotton, Coriander, and Murraya) of honey crystallize faster than Dalbergia honey in the present study. The tendency of crystallization is slower with F/G values above 1.3 (Dobre et al. 2012).

Rheological measurements

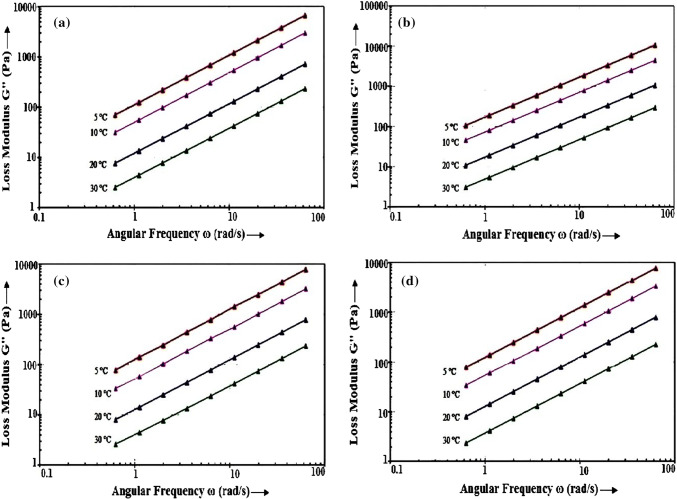

Dynamic frequency sweep experiments were performed to measure rheological behaviour viz. loss modulus (G″) and storage modulus (G′) of four honey varieties (n = 67) of Cotton, Coriander, Dalbergia and Murraya at an angular frequency ranging from 0.63 to 63 rad/s and their dependence on angular frequency. It was analyzed from the data that loss modulus (G″) was higher as well as considerable in comparison to storage modulus (G′) which indicated that four honey types exhibited viscous behaviour. Various researchers furthermore described the dominance of viscous behaviour in different types of honey (Juszczak and Fortuna 2006; Witczak et al. 2011; Nayik et al. 2016). In the present investigation, rheological parameters G′ and G″ increased by increasing angular frequency in all honey types. The frequency dependent magnitude obtained for G″ implies viscous behaviour of honey while value of G′ implies its elastic behaviour. The G″ values could be used to predict the viscous behaviour of honey (Witczak et al. 2011).

Figure 1a–d depicts loss modulus (G″) as a function of angular frequency at 5, 10, 20 and 30 °C. As G″ is more informative and G″ > G′ revealed the viscous behaviour of honey samples, so in this investigation, effect of temperature on the rheological properties of honey was considered by G″ parameter only. In this study, difference in G′ and G″ among four varieties of analyzed honey was found, the reason possibly owing to differences in pollen spectra, moisture content and sugar composition (Lazaridou et al. 2004). The values for G″ ranging from 227.4 Pa in curry leave honey at 30 °C to 10,553 Pa in Coriander honey at 5 °C whereas, G′ varied from 0.012 Pa in Cotton honey at 30 °C to 163.47 Pa in Coriander honey at 5 °C. The descending order of loss modulus (G″) of four honey samples is revealed in Supplementary Fig. 2, i.e., Coriander honey followed by Murraya honey, Dalbergia honey and Cotton honey.

Fig. 1.

a–d Loss modulus (G″) versus angular frequency (ω) for honey samples of a Cotton, b Coriander, c Dalbergia and d Murraya at various temperatures (5, 10, 20 and 30 °C)

The viscosity of honey is strongly affected by moisture content and chemical composition, further the results may also differ owing to natural variations viz. season, geographical area and source of honey (Zaitoun et al. 2001; Lazaridou et al. 2004; Juszczak and Fortuna 2006). The data achieved for storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) at 5, 10, 20 and 30 °C were subjected to linear regression.

The magnitudes of intercepts (K), slopes (n) and the coefficient of regression (R2) for Power law equations are shown in Table 2. The rheological data found from Power law equations shows that honey exhibited Newtonian behaviour as magnitudes of K″ (3.70–169.25) are greater than K′ (0.02–1.96) and flow behaviour index of honey n″ = 0.99–1. with high dependence (n′ = 0.01–1.55, n″ = 0.99–1) on frequency. Similar results were reported by Nayik et al. (2016) in Indian honey. The viscosity was independent of angular frequency or shear rate, which verified the Newtonian behaviour of honey as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3a–d. These results were comparable with various researchers from other corners of the World (Abu-Jdayil et al. 2002; Lazaridou et al. 2004; Juszczak and Fortuna 2006; Ahmed et al. 2007; Wei et al. 2010; Witczak et al. 2011; Saxena et al. 2014).

Table 2.

Slopes and intercepts of storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) versus angular frequency (ω) of different honey varieties

| Honey | Temperature (oC) | G′ | G″ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n′ | K′ | R2 | n″ | K″ | R2 | ||

| Cotton | 5 | 1.17 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 111.06 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 1.05 | 0.59 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 49.51 | 0.99 | |

| 20 | 0.90 | 0.25 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 11.94 | 0.99 | |

| 30 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.99 | 3.89 | 0.99 | |

| Coriander | 5 | 1.55 | 0.27 | 0.99 | 1 | 169.25 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 1.48 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 72.11 | 0.99 | |

| 20 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 1 | 17.06 | 0.99 | |

| 30 | 1.24 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 4.79 | 0.99 | |

| Dalbergia | 5 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.81 | 1 | 124.75 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 0.66 | 1.96 | 0.86 | 1 | 50.59 | 0.99 | |

| 20 | 0.19 | 0.79 | 0.19 | 1 | 12.47 | 0.99 | |

| 30 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 3.77 | 0.99 | |

| Murraya | 5 | 1.34 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 1 | 124.71 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 1.29 | 0.15 | 0.99 | 1 | 53.24 | 0.99 | |

| 20 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 1 | 12.68 | 0.99 | |

| 30 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 3.70 | 0.99 | |

Where n′ and K′ are elastic slope and intercept, respectively and K″ and n″ are viscous slope and intercept, respectively

The viscosity of four honey samples as a function of temperature is presented in Table 3. The viscosity of all honey samples decreases with increasing temperature (Supplementary Fig. 4) because intermolecular forces decreased with increase in temperature, i.e., with an increase in kinetic energy molecules become more movable (Patil and Muskan 2009). The viscosity of honey samples varied from 3.89 Pa.s at 30 °C in Murraya honey to 185.13 Pa.s at 0 °C in Coriander honey. These findings were consistent with the values recorded by Juszczak and Fortuna (2006) for Polish honey and Nayik et al. (2016) for Indian honey. Costa et al. (2013) reported that viscosity of Brazilian honey ranged from 0.19 to 6.65 Pa.s. In Chinese honey viscosity ranged from 0.3 to 6.3 Pa.s (Junzheng and Changying 1998) at 20 °C, but this range was less than Jordanian honey, i.e., 12.18–30 Pa.s (Abu-Jdayil et al. 2002) at 25 °C. Because of the existence of large crystals of glucose in honey, low deformation stress is observed while shear is applied. Consecutively, to recognize the flow characteristics of honey at a molecular and structural level during the rheological characterization fructose, glucose and F/G ratio are mainly significant factors which should be considered (Dobre et al. 2012).

Table 3.

Viscosity of different honey as a function of temperature

| Honey | Temperature (oC) | Viscosity (Pa.s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cotton | 5 | 121.02 |

| 10 | 57.41 | |

| 20 | 13.86 | |

| 30 | 4.17 | |

| Coriander | 5 | 185.13 |

| 10 | 84.94 | |

| 20 | 18.99 | |

| 30 | 5.21 | |

| Dalbergia | 5 | 135.88 |

| 10 | 62.54 | |

| 20 | 14.39 | |

| 30 | 4.162 | |

| Murraya | 5 | 133.88 |

| 10 | 64.03 | |

| 20 | 14.72 | |

| 30 | 3.89 |

Effect of temperature on viscosity (η) and loss modulus (G″) of honey

The Arrhenius equation illustrated the effect of temperature on viscosity and loss modulus of honey. The activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponent factor (η0) of the Arrhenius equation was calculated from the slope and intercept of the straight line, respectively by least square regression. The effect of temperature on viscosity via Arrhenius equation was depicted and the activation energy of studied honey samples varied from 94.51 kJ/mol in Cotton honey to 100.19 kJ/mol in Coriander honey (Table 4). Activation energy is a sign of the sensitivity of viscosity towards high temperature. Higher activation energy indicated that these parameters of honey are more responsive to temperature variation.

Table 4.

Temperature dependency of rheological parameters

| Honey samples | Viscosity (μ) | Loss modulus (G″) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ea (kJ/mol) | ηo (mPa.s) | R2 | Ea (kJ/mol) | Go (mPa.s) | R2 | |

| Cotton | 94.51 | 2.06 × 10−16 | 0.99 | 94.27 | 1.23 × 10−14 | 0.99 |

| Coriander | 100.19 | 2.72 × 10−17 | 0.99 | 99.66 | 1.88 × 10−15 | 0.99 |

| Dalbergia | 97.80 | 5.56 × 10−17 | 0.99 | 97.47 | 1.99 × 10−16 | 0.99 |

| Murraya | 99.31 | 2.94 × 10−17 | 0.99 | 98.56 | 2.22 × 10−15 | 0.99 |

The activation energy was highest in Coriander honey (99.66 kJ/mol) followed by Murraya (98.56 kJ/mol), Dalbergia (97.47 kJ/mol) and Cotton (94.27 kJ/mol) honey as shown in Table 4. These results depicted that Cotton honey has lowest activation energy; as a result, it is least sensitive, while Coriander honey has highest activation energy consequently this honey is most sensitive to temperature amongst studied honey varieties. Comparable results were also recorded for Greek honey (Lazaridou et al. 2004), Polish honey (Juszczak and Fortuna 2006) and Indian honey (Nayik et al. 2016). Al-Malah et al. (2001) reported that the material constant (pre-exponent) characterizes viscosity at a temperature approaching infinity. Figure 2 depicts a linear correlation of ln(η) versus (1/T) achieved from the Arrhenius equation and well fitted to experimental data. The Arrhenius model explained the akin effect of temperature on loss modulus (G″).

Fig. 2.

Arrhenius model fit for different types of unifloral honey

Conclusion

The sugar profile of all analyzed honey samples indicated that all honey varieties have reducing sugars, chiefly glucose and fructose in a major amount and little quantities of disaccharides and trisaccharides. Fructose and glucose were in the range of 36.86–41.15% and 33.40–34.06%, respectively. Low amounts of turanose, trehalose, melibiose, and raffinose were present in the range of 0.02–0.03%, 0.11–0.26%, 0.09–0.18% and 0.06–0.12%, respectively. All analyzed honey varieties confirmed Newtonian behaviour (G″ > G′) at 5, 10, 20 and 30 °C. The results furthermore depicted that honey with the highest activation energy is more sensitive to a temperature gradient.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to local beekeepers of Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, and Rajasthan (India) for providing honey samples.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abu-Jdayil B, Ghzawi A, Al-Malah KIM, Zaitoun S. Heat effect on rheology of light and dark-coloured honey. J Food Eng. 2002;51:33–38. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(01)00034-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed J, Prabhu S, Raghavan G, Ngadi M. Physico-chemical, rheological, calorimetric and dielectric behaviour of selected Indian honey. J Food Eng. 2007;79:1207–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.04.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Malah KIM, Abu-Jdayil B, Zaitoun S, Al-Majeed Ghzawi A. Application of WLF and Arrhenius kinetics to rheology of selected dark-colored honey. J Food Eng. 2001;24:341–357. [Google Scholar]

- Bentabol Manzanares A, Hernandez Garcia Z, Rodriguez Galdon B, Rodriguez Rodriguez E, Diaz Romero C. Differentiation of blossom and honeydew honeys using multivariate analysis on the physicochemical parameters and sugar composition. Food Chem. 2011;126:664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission (2001) Revised standards for honey. Codex Standard 12-1981. Rev 1 (1987), Rev 2 (2001), Rome, FAO, 2001

- Costa PA, Moraes ICF, Bittante AMQB, Sobral PJA, Gomide CA, Carrer CC. Physical properties of honeys produced in the Northeast of Brazil. Int J Food Stud. 2013;2:118–125. doi: 10.7455/ijfs/2.1.2013.a9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotte JF, Casabianca H, Chardon S, Lheritier J, Grenier-Loustalot MF. Application of carbohydrate analysis to verify honey authenticity. J Chromatogr A. 2003;1021:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente E, Ruiz-Matute AI, Valencia-Barrera RM, Sanz J, Martinez-Castro I. Carbohydrate composition of Spanish unifloral honeys. Food Chem. 2011;129:1483–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.05.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobre I, Georgescu LA, Alexe P, Escuredo O, Seijo MC. Rheological behaviour of different honey types from Romania. Food Res Int. 2012;49:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escuredo O, Miguez M, Fernandez-Gonzalez M, Seijo MC. Nutritional value and antioxidant activity of honeys produced in a European Atlantic area. Food Chem. 2013;138:851–856. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escuredo O, Dobre I, Fernandez-Gonzalez M, Seijo MC. Contribution of botanical origin and sugar composition of honeys on the crystallisation phenomenon. Food Chem. 2014;149:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junzheng P, Changying J. General rheological model for natural honeys in China. J Food Eng. 1998;36:165–168. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(98)00050-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juszczak L, Fortuna T. Rheology of selected polish honeys. J Food Eng. 2006;75:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.03.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juszczak L, Socha R, Roznowski J, Fortuna T, Nalepka K. Physicochemical properties and quality parameters of herb honeys. Food Chem. 2009;113:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj R, Bera MB, Nanda V. Evaluation of physico-chemical properties, trace metal content and antioxidant activity of Indian honeys. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2013;48:578–587. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.12002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj R, Bera MB, Nanda V. Chemometric classification of Northern India unifloral honey. Acta Aliment Hung. 2013;42:540–551. doi: 10.1556/AAlim.42.2013.4.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalafi R, Goli SAH, Isfahani MB. Characterization and classification of several monofloral Iranian honeys based on physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity. Int J Food Prop. 2016;19:1065–1079. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2015.1055360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laos K, Kirs E, Pall R, Martverk K. The crystallisation behaviour of Estonian honeys. Agron Res. 2011;9:427–432. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridou A, Biliaderis CG, Bacandritsos N, Sabatini AG. Composition, thermal and rheological behaviour of selected Greek honeys. J Food Eng. 2004;64:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2003.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nayik GA, Nanda V. A Chemometric approach to evaluate the phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity and mineral content of unifloral honey types from Kashmir, India. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2016;74:504–513. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nayik GA, Dar BN, Nanda V. Physico-chemical, rheological and sugar profile of different unifloral honeys from Kashmir valley of India. Arab J Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nozal MJ, Bernal JL, Toribio L, Alamo M, Diego JC. The use of carbohydrate profiles and chemometrics in the characterisation of natural honeys of identical geographical origin. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:3095–3100. doi: 10.1021/jf0489724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchemoukh S, Schweitzer P, Bachir Bey M, Djoudad-Kadji H, Louaileche H. HPLC sugar profiles of Algerian honeys. Food Chem. 2010;121:561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.12.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil U, Muskan K. Essentials of biotechnology. New Delhi: International Publishing House; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Persano Oddo L, Piro R. Main European unifloral honeys: descriptive sheets. Apidologie. 2004;35:38–81. doi: 10.1051/apido:2004049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Primorac L, Flanjak I, Kenjeric D, Bubalo D, Topolnjak Z. Specific rotation and carbohydrate profile of croatian unifloral honeys. Czech J Food Sci. 2011;29:515–519. doi: 10.17221/164/2010-CJFS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak-Chmielewska H, Szczesna T, Was E, Jaskiewicz K, Teper D. Characteristics of Polish unifloral honeys IV honeydew honey, mainly Abies alba L. J Apic Sci. 2013;57:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz ML, Polemis N, Morales V, Corzo N, Drakoularakou A, Gibson GR, et al. In vitro investigation into the potential prebiotic activity of honey oligosaccharides. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:2914–2921. doi: 10.1021/jf0500684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Panicker L, Gautam S. Rheology of Indian honey: effect of temperature and gamma radiation. Int J Food Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/935129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senyuva HZ, Gilbert J, Silici S, Charlton A, Dal C, Gurel N, Cimen D. Profiling Turkish honeys to determine authenticity usingphysical and chemical characteristics. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:3911–3919. doi: 10.1021/jf900039s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopade PA, Halley PJ, D’Arcy BR, Bhandari B, Caffin N. Dynamic and steady-state rheology of Australian honeys at subzero temperatures. J Food Process Eng. 2004;27:284–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4530.2004.00468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szczesna T, Rybak-Chmielewska H, Was E, Kachaniuk K, Teper D. Characteristics of Polish unifloral honeys. I. Rape honey (Brassica napus L. var. Oleifera Metzger) J Apic Sci. 2011;55:111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Von der Ohe W, Persano Oddo L, Piana ML, Morlot M, Martin P. Harmonized methods of melissopalynology. Apidologie. 2004;35:S18–S25. doi: 10.1051/apido:2004050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Wang J, Wang Y. Classification of monofloral honeys from different floral origins and geographical origins based on rheometer. J Food Eng. 2010;96:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witczak M, Juszczak L, Gałkowska D. Non-Newtonian behaviour of heather honey. J Food Eng. 2011;104:532–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitoun S, Ghzawi AA, Al-Malah KIM, Abu-Jdayil B. Rheological properties of selected light coloured Jordanian honey. Int J Food Prop. 2001;4:139–148. doi: 10.1081/JFP-100002192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.