Abstract

Surimi gels containing β-glucan stabilized virgin coconut oil (VCO) were subjected to simulated gastrointestinal digestion and the resulting digest was analyzed for nutraceutical properties. β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion (βG-V-N) remarkably improved antioxidant activities of the surimi digest. When epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) was added in nanoemulsion, the surimi digest showed the highest antioxidant activities. Antidiabetic activity of the digest was also improved by the addition of βG-V-N comprising EGCG. Nevertheless, the addition of βG-V-N lowered ACE inhibitory activity of surimi digest. The surimi digest from the gel added with βG-V-N possessed an inhibitory effect on five cancer cell lines including HEK (Human embryonic kidney 293 cells), MCF-7 (breast cancer cell line), U87 (human glioma), HeLa (human cervical cancer), and IMR-32 (human neuroblastoma), regardless of EGCG or α-tocopherol incorporated. This study demonstrated that surimi gel supplemented with βG-V-N in the presence of EGCG exhibited nutraceutical potential and could be used as a functional food.

Keywords: Surimi gel, Nanoemulsion, β-Glucan, Antioxidant, Nutraceutical property

Introduction

Surimi rich in myofibrillar proteins can form gel when subjected to hydro-thermal processing. It is highly nutritious with delicacy, mainly due to the elastic texture. Physical and textural properties of surimi gels have been improved with the addition of different ingredients or additives. Addition of virgin coconut oil (VCO) at 5% level has resulted in whiter gel without any deleterious effect on gel properties (Gani and Benjakul 2019). Surimi gel properties were modified by the addition of various vegetable oils including peanut, rapeseed, soybean, and corn oils (Shi et al. 2014). Incorporation of gellan in both powder and suspension forms increased water holding capacity, hardness, whiteness and breaking force of surimi gel when the gellan amounts were augmented (Petcharat and Benjakul 2018). In addition, the improvement of surimi gel quality could be achieved by incorporating some ingredients such as egg white proteins (Zhou et al. 2019). Microbial transglutaminase (MTGase) has been widely employed to strengthen the gel, especially from surimi with low setting phenomenon (Chanarat et al. 2012). Furthermore, the use of MTGase could increase the gelling property of Indian mackerel fish protein isolate more effectively than mince and surimi (Chanarat and Benjakul 2013).

VCO is generally obtained from coconut milk, meat or residue in which any chemical refining, bleaching or deodorization is omitted. Production can be done at low temperature. VCO contains natural vitamin E and lauric acid, which resists to oxidation and has incredible health benifits (Senphan and Benjakul 2017). VCO is considered as a functional oil due to its several biological activities involving antiviral and antimicrobial activities (Rohman and Che Man 2011). Recently, β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion (βG-V-N) has been added as a functional ingredient and was able to augment the textural properties, whiteness and acceptability of surimi gel (Gani and Benjakul 2019). Nanoemulsion addition yielded the gel with better properties than the direct incorporation of VCO. β-glucan is reported to help treatment and management of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, hyperlipidemia and cancer. The health benefits of β-glucan are fundamentally due to its fermentability and formation of high viscosity solutions in the intestines (Bozbulut and Sanlier 2019). β-glucan is regarded as biological response modifier due to its ability to modulate immune system (Shah et al. 2015). Recently, Sinthusamran and Benjakul (2018) reported the increased antioxidant activity of fish gelatin gels incorporated with β-glucan in the simulated gastrointestinal tract model.

Peptides in protein hydrolysate from various sources have been proven to possess a wide range of bioactivities. Ko et al. (2016) isolated two angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from pepsin hydrolysates of flounder fish muscle. Ramadhan et al. (2017) identified five novel antidiabetic peptides from Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) protein hydrolysate. Stability of bioactive peptides during gastrointestinal transit is an important parameter governing bioactivity of peptides. In vitro digestion models have been used to mimic the digestion process and are used to study the digestibility and release behaviour of food components under simulated gastrointestinal conditions (Hur et al. 2011; Sae-leaw et al., 2016). Gastrointestinal proteinases could modify the peptides passing through the gastrointestinal tract, thus altering bioactive properties including antioxidant properties (Sae-leaw et al. 2016; Khantaphant et al. 2011). Gamez et al. (2015) reported that simulated gastric digestion reduced IgE reactivity of shrimp proteins and hence digestion could reduce shrimp allergenicity while maintaining the immunogenicity. Antioxidative peptides may be released by the action of pancreatin toward hydrolysates from seabass skin during digestion, leading to the generation of more potent bioactive peptides (Senphan and Benjakul 2014). Generation of bioactive peptides during simulated gastrointestinal digestion could reflect the spectrum of bioactivities of the surimi digest including antioxidant properties, antidiabetic properties, antihypertensive properties and anticancer properties, etc.

Due to high content of proteins in surimi, peptides or free amino acids after digestion have been documented to have a variety of bioactivities. These peptides have shown broad spectrum of bioactivities including immunomodulatory (Chalamaiah et al. 2018). As an ideal food matrix for supporting high quality protein, the gastrointestinal digestion of surimi gel is imperative for development of surimi based products with enhanced nutraceutical value and regulated release of nutrients in the gastric tract (Fang et al. 2019). Anticancer activity has been documented in hydrolysates as well as peptides derived from a variety of food proteins (Chalamaiah et al. 2018). Flounder surimi digest (FSD) exhibited ACE inhibitory activity after an in vitro gastric model (Oh et al. 2019). Similarly, Wang et al. (2014) found an increase in degree of hydrolysis in gelatin from 0.17 to 26.08%, while the DPPH radical scavenging rate increased from 1.20 to 44.76% under simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Although surimi gel containing β-glucan stabilized VCO was developed, no information on nutraceutical properties has been reported, particularly in the conjunction of antioxidant incorporation.

The in vitro antioxidant, antidiabetic, hypertensive and anticancer properties of the digest from surimi gels added with βG-V-N in the absence or presence of selected antioxidants were evaluated.

Materials and methods

Materials, chemicals and cell lines

Frozen sardine surimi (AA) grade, VCO and β-glucan (70% purity) were purchased from Pacific Fish Processing Co., Ltd. (Songkhla, Thailand), Posture Trading, Ltd. (Pathumthani, Thailand) and Hangzhou Asure Biotech Co, Ltd. (Hangzhou, China), respectively. All other chemicals used for analysis were procured from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Five cancer cell lines HEK (Human embryonic kidney 293 cells), MCF-7 (breast cancer cell line), U87 (human glioma), HeLa (human cervical cancer), and IMR-32 (human neuroblastoma) were obtained from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India.

Preparation of β-glucan-stabilized VCO nanoemulsion (βG-V-N) containing antioxidants

βG-V-N was prepared with the aid of ultrasonication as detailed by Gani and Benjakul (2019). Firstly 5% VCO (based on total surimi paste) and 5% β-glucan solutions (based on surimi dry weight) were prepared. EGCG or α-tocopherol were dissolved in water and VCO respectively, to obtain the level of 0.2% each, based on protein content in surimi. All the mixtures were homogenized for 5 min at 11,000 rpm. This was followed by ultrasonication for 5 min at 60% amplitude as tailored by Gani and Benjakul (2019).

Preparation of surimi gel containing VCO nanoemulsion

Frozen surimi was thawed until core temperature reached 0–2 °C. After thawing, surimi block was reduced to small pieces and it was minced in a Moulinex Masterchef 350 mixer (Paris, France) for 1 min. To surimi paste, 2.5% salt was added and mixed for another 1 min. For the samples containing βG-V-N without or with antioxidants, the prepared nanoemulsions were incorporated into paste to possess the final VCO, β-glucan and antioxidant levels of 5, 5 and 0.2% based on surimi paste, dry matter and protein content of surimi, respectively. The paste was mixed again for 1 min. The control was also prepared without addition of βG-V-N.

The pastes were filled and sealed in polyvinylidene casing (25 mm in diameter). Gel setting was done at 40 °C and 90 °C for 30 min and 20 min, respectively using a water bath (Memmert, Schwabach, Germany). Subsequently gels were subjected to cooling using iced water. The gel samples were kept at 4 °C for 24 h before analysis.

Simulated gastrointestinal tract digestion

Simulated gastrointestinal tract model system (GIMS) was adopted as detailed by Sinthusamran and Benjakul (2018) with some modifications. Surimi gels were immersed in liquid nitrogen followed by pulverizing in a mixer to produce a fine powder. The sample (10 g) was taken and homogenized with 100 mL of phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2 (8 g L−1 NaCl, 1.91 g L−1 Na2HPO4, 0.38 g L−1 KH2PO4). To mimic the oral conditions, 200 mg of α-amylase was added into the solution (pH = 7.2). The mixture was preheated for 5 min to 37 °C with continuous shaking (shaking waterbath). Subsequently pH of solution was adjusted to 2 using 1 M HCl, followed by addition of 400 mg pepsin into the solution. The mixture was further incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with continuous shaking. Thereafter, 1 M NaOH was added to raise pH to 5.3 followed by addition of 200 mg pancreatin and 67 mg bile salt. Subsequently, pH of the mixture was raised to 7.5 using 1 M NaOH and the mixture was incubated at the same temperature for 3 h with continuous shaking. The enzyme reaction was terminated by placing the sample in boiling water at 100 °C for total 10 min. The digest was centrifuged at 12000×g for 10 min and the supernatant was obtained and kept at − 40 °C for analysis. The digest from control surimi gel was referred to as ‘C’. The digest from surimi gel added with βG-V-N was named ‘Dig-N’ while those added with βG-V-N with EGCG and α-tocopherol were termed ‘Dig-N-EG’ and ‘Dig-N-TC’, respectively.

Determination of antioxidant activities

DPPH radical scavenging activity (DRSA)

The procedure of Maqsood and Benjakul (2010) was followed for DRSA. The calibration curve of Trolox (0–600 μM) was used for estimation.

ABTS radical-scavenging activity (ARSA)

The protocol of Sinthusamran and Benjakul (2018) was adopted for ARSA. The calibration curve of Trolox (0–600 μM) was used for estimation.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

FRAP was determined as tailored by Maqsood and Benjakul (2010) with minor modification. The calibration curve of Trolox (0–60 μM) was prepared.

Reducing power (RP)

RP was determined by the procedure of Sinthusamran and Benjakul (2018). Trolox (0–60 μM) was used for standard curve.

Ferrous chelating activity (FCA)

FCA was estimated as tailored by Khantaphant et al. (2011). The standard curve of EDTA ranging from 0 to 60 μM was used.

Activities of DRSA, ARSA, FRAP and RP were expressed as μmol Trolox equivalent (TE)/g sample. Activity of FCA was reported as μmol EDTA equivalents (EE)/g sample.

Antidiabetic activity

α-Glucosidase inhibition assay (GIA)

GIA was estimated as detailed by Ahmad et al. (2019) with minor modification. Sample (50 μL) was added to 4 mM 4-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (pNPG) (25 μL), prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 and 50 μL of α-glucosidase enzyme solution (0.2 U/mL) from yeast and mixed in 96 well plate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and the absorbance was read at 405 nm. The inhibition percentage was calculated as shown below:

where A: Control, B:Control Blank, C:Reaction, D:Reaction blank.

Antihypertensive activity

ACE inhibitory activity (ACE-IA)

ACE-IA was examined as tailored by Chalamaiah et al. (2015) with a slight modification. Sample (50 μL) was mixed with ACE solution (50 μL, 50 mU/mL). This mixture was pre-incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Subsequently 100 μL of substrate (8.3 mM Hip-His-Leu in 50 mM sodium borate buffer containing 0.3 M NaCl, pH 8.3) was added. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. For the control, distilled water was used instead of sample. The enzymatic reaction was terminated using 500 μL of 1 M HCl. Ethyl acetate (1.5 mL) was used to extract hippuric acid. This was followed by centrifugation (3000×g for 10 min) and evaporation of 1 mL upper layer to dryness at 80 °C. Hippuric acid was dissolved with 1 mL of distilled water and absorbance was read at 228 nm. The ACE-IA was calculated using the following formula:

Antiproliferative assay

Anticancer activity was examined by the method detailed by Chalamaiah et al. (2015) with some modifications. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) added with 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic was used to maintain the cells. Humidified incubator (37 °C and 5% CO2 level) was used to grow the cells.

After achieving desired confluency, 200 μL of cell suspension was seeded in 96-well plate, followed by incubation for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator. The media were carefully removed. Wells were then replenished with fresh media (150 μL) and sample (150 μL). Incubation was done at 37 °C for another 24 h in a humidified CO2 incubator. For control wells, no sample was added. After incubation, the contents of the wells were carefully removed and 20 μL of tetrazolium dye [MTT 3- (4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (5 mg/mL in DMSO) was added to each well in dark. The 96-well plate was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h in CO2 incubator. The precipitates formed were dissolved by adding DMSO (150 μL) and shaking for 15 min. The absorbance of 96-well plate was read at 590 nm and % inhibition was estimated as follows:

Statistical analysis

Completely randomized design was used for the whole experiment. Three different lots of samples were used to run the experiments. The data was subjected to Analysis of Variance and the Duncan’s multiple range was used for mean comparison (Steel and Torrie 1980). Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 11.0 for windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software was adopted for statistical analysis of the data.

Results and discussion

Simulated gastrointestinal digestion is used as it is rapid, safe, inexpensive and without ethical constraints unlike in vivo methods. During recent time, it has been used to evaluate the bioavailability as well as bioactivity of proteins (Wang et al. 2014). Simulated digestion of surimi gel is expected to release the bioactive peptides with nutraceutical properties.

Antioxidative activities of the digest of surimi gels added without and with βG-V-N and antioxidants from GIMs

DRSA

DRSA of the digests of all the samples were in the range of 401–600 μM Trolox equivalent/g sample (Fig. 1a). Surimi gels containing βG-V-N without or with added antioxidants (α-tocopherol or EGCG) exhibited higher scavenging ability, than the control (p < 0.05). The highest activity was attained for Dig-N-EG sample (p < 0.05). Therefore, in addition to the peptides generated during digestion in GIMs, βG-V-N as well as EGCG remarkably contribute towards DPPH scavenging ability of the digest. The result revealed that the surimi digests most likely contained peptides, which were electron donors and terminated the radical chain reaction. Ultrasonic treatment during the preparation of βG-V-N plausibly degraded the β-glucan to expose functional groups, especially –COOH, >C=O, resulting in the increase in the activity. Hussain et al. (2018) found that increase in DRSA of γ-irradiated β-glucan due to the creation of new functional groups as a consequence of radiation degradation. García-Moreno et al. (2014) reported DRSA of sardine and horse mackerel protein hydrolysates with varying EC50 values (0.91–1.78 mg protein/mL). Similarly, sardinelle (Sardinelle aurita) hydrolysate had 53.76% scavenging activity towards DPPH at 2 mg/mL (Bougatef et al. 2010). β-glucan itself also had antioxidant activity. Shah et al. (2017) documented that oat β-glucan showed higher DRSA than barley β-glucan. The radical scavenging ability of β-glucan was linked to the hydrogen atoms in its structure, which could be donated to free radicals (Shah et al. 2015). EGCG was reported to show DRSA in duck egg hydrolysate (Quan and Benjakul 2019), while α-tocopherol has been known to be a lipid soluble antioxidant (Palozza and Krinsky 1992). The higher degree of hydroxylation in EGCG was most likely linked to its capability of scavenging free radicals (Maqsood and Benjakul, 2010). Therefore, the combined effect of peptides, β-glucan and added antioxidants, either EGCG or α-tocopherol contributed to the increased DRSA of the digest.

Fig. 1.

DPPH radical scavenging activity (a), ABTS radical scavenging activity (b), metal chelating activity (c), reducing power (d) and FRAP (e) of digest of surimi gel added without and with β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion in the presence and absence of EGCG or α-tocopherol. C, control surimi gel; Dig-N, surimi gel added with β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion; Dig-N-EG, surimi gel added with β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion containing epigallocatechin gallate; Dig-N-TC, surimi gel added with β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion containing α-tocopherol. Bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences (p < 0.05)

ABTS radical-scavenging activity (ARSA)

ARTS of the digest from surimi gel incorporated without and with βG-V-N without and with antioxidants is shown in Fig. 1b. ARTS was increased in Dig-N sample, compared with C sample (p < 0.05). Nevertheless, Dig-N-EG sample had the highest ARSA (p < 0.05). No difference in ARSA was found between Dig-N sample and Dig-N-TC sample. The activity ranged from 190 to 245 μM Trolox equivalent/g sample. The tendency of antioxidants to donate hydrogen atom to ABTS and convert it to a non-radical measures its ARSA (Sinthusamran and Benjakul 2018). The seabass skin gelatin hydrolysates prepared using protease showed the increase in ARSA when subjected to simulated gastrointestinal digestion (Senphan and Benjakul 2014). The antioxidative activity of surimi gel was augmented in the gastrointestinal tract by the addition of βG-V-N containing antioxidants. Pancreatin (mixture of amylase, lipase and protease) might cleave β-glucan (Sinthusamran and Benjakul 2018). However, the role of ultrasonication in cleavage and production of small molecular weight β-glucan fragments could not be ruled out. Low molecular weight products produced from β-glucan could also be partially responsible for the increased ARSA (Hussain et al. 2018). Both EGCG and α-tocopherol also contributed to ARSA. Among all the samples, Dig-N-EG sample showed the highest ARSA after digestion.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

FRAP of digest from surimi gel containing βG-V-N in the absence or presence of antioxidants is depicted in Fig. 1c. FRAP measures the ability of sample to reduce TPTZ-Fe(III) complex to TPTZ-Fe(II) complex (Senphan and Benjakul 2014). Dig-N sample had higher FRAP, compared to C sample (without nanoemulsion) (p < 0.05). However, the FRAP of both Dig-N-EG and Dig-N-TC were higher, compared with Dig-N sample (p < 0.05). Generally the FRAP value of surimi digests gradually augmented as βG-V-N was added (p < 0.05) and ranged from 9.8 to 32.5 μM Trolox equivalent/g sample (Fig. 1c). The reducing ability is attributed to the presence of reducing sugars and hydrogen donating ability of β-glucan fragment induced by ultrasound (Hussain et al. 2018). Sinthusamran and Benjakul (2018) also reported that the addition of β-glucan up to 20% level augmented FRAP of the resulting digest in simulated gastrointestinal model. Among all samples, Dig-N-EG sample had the highest FRAP (p < 0.05). The increase in FRAP indicated that the surimi digest added with nanoemulsion and antioxidant, particularly EGCG was able to render an electron to stabilize free radicals, leading to prevention or suppression of propagation (Senphan and Benjakul 2014).

Reducing power (RP)

The reduction of Fe(III) complex to Fe(II) complex was used to evaluate the reductive ability of digest from surimi gel added without or with βG-V-N in the presence and absence of antioxidants (Fig. 1d). Generally, Dig-N sample had the increased reducing power of the surimi digests (p < 0.05), compared to the C sample. However, the antioxidant added samples showed stronger RP of digest than the Dig-N (p < 0.05). No difference was found between Dig-N-EG and Dig-N-TC samples (p > 0.05). The tendency of an antioxidant to provide an electron or hydrogen to free radicals is assessed by its reducing power (Bougatef et al. 2010). Sinthusamran and Benjakul (2018) reported the increase in RP of fish gelatin-β-glucan gels subjected to simulated digestion model system with increasing levels of β-glucan in the gel. Gradual increase in RP was found for the digests with progression in simulated digestion from mouth phase to duodenum phase (Sinthusamran and Benjakul 2018). In addition to the peptides generated during simulated gastrointestinal digestion having antioxidative properties (Senphan and Benjakul 2014), oligosaccharides and/or small molecular weight components from β-glucan resulted in the antioxidative property of surimi digests (Sinthusamran and Benjakul 2018). Shah et al. (2017) found a dose dependent increase in RP of barley and oats β-glucan (p < 0.05) up to 100 mg/mL concentration. However, RP of oats β-glucan was higher than that of barley at all the levels tested (p < 0.05). Ovissipour et al. (2013) reported RP in the range of 3.3–7.6 (μM TE/g protein) for anchovy sprat hydrolysates produced by various enzymes. Both EGCG and α-tocopherol drastically contributed to the enhanced RP of the digest. Thus, the combination of βG-V-N with antioxidant resulted in the digest with enhanced RP. Similar results were found for FRAP and RP (Fig. 4c, d). Both of these assays use different Fe-binding ligands, however the ability of antioxidant to reduce Fe3+ complex to Fe2+ complex can be examined (Sinthusamran and Benjakul 2018).

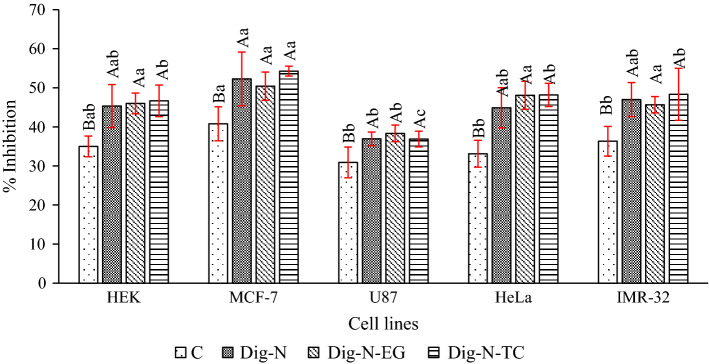

Fig. 4.

Antiproliferative activity of digest of surimi gel added without and with β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion in the presence and absence of EGCG or α-tocopherol. HEK: Human embryonic kidney 293 cells; MCF-7: breast cancer cell line; U87: human glioma; HeLa: human cervical cancer; and IMR-32: human neuroblastoma. Bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Different uppercase letters on the bars within same cell line indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Different lowercase letters on the bars within same digest indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Key: For caption, see Fig. 1

Metal-chelating activity (MCA)

MCA of digest from surimi gel added without and with βG-V-N alone or in combination with antioxidants is depicted in Fig. 1e. Dig-N-EG sample exhibited the highest MCA (p < 0.05). However, no difference was attained in MCA between Dig-N and Dig-N-TC samples (p > 0.05). The control sample (without nanoemulsion) showed the lowest ability to chelate metal ions. MCA ranged from 2.69 ± 0.17 to 3.70 ± 0.23 (μM EE/g sample). Senphan and Benjakul (2014) found the increased MCA of hydrolysate (40% DH) produced from seabass skin, in the duodenal condition after being ingested in simulated gastrointestinal model system (SGMs). Khantaphant et al. (2011) found that enhanced antioxidative activity of flavourzyme protein hydrolysate produced from brownstripe red snapper, after SGMs. Transition metals ions like Cu2+ and Fe2+ catalyze the generation of reactive oxygen species which induces lipid peroxidation. Therefore, the capacity of peptides to bind the transition metals could inhibit oxidation (Stohs and Bagchi 1995). García-Moreno et al. (2014) reported EC50 values of 0.32 mg protein/mL for ferrous-chelating activity of hydrolysates from sardine and small-spotted catshark. The availability of effective metal chelating sites in hydrolysates more likely corresponds to its metal binding capacity (Ovissipour et al. 2013).

β-glucan–Fe2+complexes, might also increase MCA of the digest. Hussain et al. (2018) and Shah et al. (2015) also found an increase in MCA of γ-irradiated (15 kGy) oat ß-d glucan by 20% when tested at 1000 µg/mL and 45% increase in chelating ability of barley β-glucan upon irradiation treatment of 8 kGy, respectively. EGCG has been known to be able to chelate metal ions due to its adjacent trihydroxy structure, in which electrons are donated by oxygen atoms to form bonds with the metal ions (Zhong et al. 2012). EGCG has been reported to chelate metal ions like zinc, copper, iron, which are reported to be linked with various biological activities (Liu et al. 2017). Therefore, addition of βC-V-N with EGCG remarkably improved MCA of the digest.

α-Glucosidase inhibition assay (GIA)

GIA of different surimi digests is depicted in Fig. 2. C sample had the lowest GIA, compared to others (p < 0.05). C sample showed less than 10% inhibition towards α-glucosidase, however Dig-N sample showed remarkable α-glucosidase inhibition (up to 35%). Peptides generated after digestion might contribute to inhibition of α-glucosidase. Matsui et al. (1999) isolated two α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides from sardine muscle hydrolysate prepared using alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis. The peptides were identified as Try-Tyr-Pro-Leu (IC50 = 3.7 mM) and Val-Trp (IC50 = 22.6 mM). The possible mechanism of inhibition was that peptides possibly interacted via hydrophobic bonds at the active site of enzyme.

Fig. 2.

α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of digest of surimi gel added without and with β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion in the presence and absence of EGCG or α-tocopherol. Bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Key: For caption, see Fig. 1

Apart from peptides, Hussain et al. (2018) reported GIA of oats β-glucan which was increased by gamma irradiation. Kardono et al. (2013) isolated crude β-glucan from silver ear mushroom at 50 ppm having GIA with IC50 value of 41.61%. Dig-N-EC and Dig-N-TC showed high inhibition towards α-glucosidase. Xu et al. (2019) demonstrated that the GIA of EGCG (IC50 = 19.5 µM) was higher than that of acarbose (IC50 = 278.7 µM). The inhibition was reversible and non-competitive. EGCG binding sites were in proximity to the active site of α-glucosidase as revealed by molecular docking. The inhibitory activity of EGCG possibly attributed to galloyl group bonding at the 3 position of catechins and was governed by the number of hydroxyl group on the B ring (Liu et al. 2016). Therefore, the surimi gels added with βG-V-N with antioxidants can generate functional bioactives with promising antidiabetic properties.

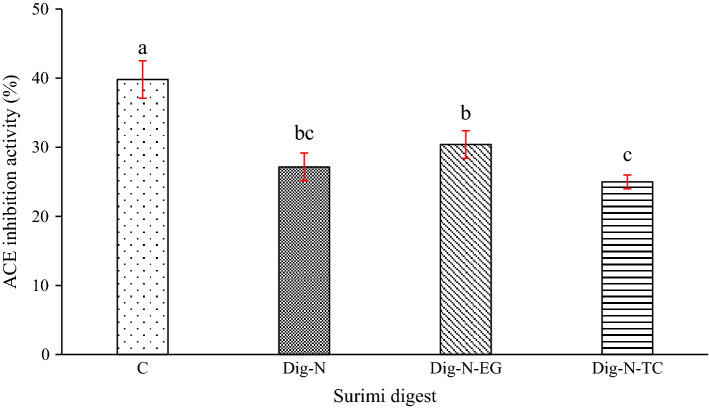

ACE inhibitory activity (ACE-IA)

The digests surimi added without and with antioxidant loaded with βG-V-N were analyzed for ACE-IA as shown in Fig. 3. ACE-IA was in the range of 25–40%. C sample had the highest ACE-IA (p < 0.05), compared to other samples. Dig-N-EG sample showed higher ACE-IA activity than Dig-N-TC sample (p < 0.05). ACE is allosterically inhibited by EGCG, probably through conversion into an electrophilic quinone and subsequent binding to ACE (Liu et al. 2017). EGCG is reported to chelate Zn at the active site of ACE, thus contributing towards ACE-IA (Persson et al. 2006). Generally, βC-V-N decreased the ACE-IA of the surimi digest (Fig. 3). Flounder surimi digest had ACE-IA in a dose dependent manner ranging from 40 to 77% using an in vitro gastric model (Oh et al. 2019). Bioactive peptides from flounder surimi effectively bound to ACE with negative binding energy and negative CDOCKER interaction energy in an in silico docking analysis. ACE converts angiotensin I into angiotensin II (vasoconstrictor) in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and inactivates bradykinin (a potent vasodilator), in the kinin nitric oxide system (KNOS). ACE inhibition leads to lowering blood pressure by reducing vasoconstriction (Neves et al. 2017). The digest from surimi added with βG-V-N had lower activity. β-glucan might interact with ACE inhibitory peptides, thus lowering activity. Therefore, surimi digest had a potential to inhibit ACE, resulting in lowering of high blood pressure.

Fig. 3.

ACE inhibitory activity of digest of surimi gel added without and with β-glucan stabilized VCO nanoemulsion in the presence and absence of EGCG or α-tocopherol. Bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Key: For caption, see Fig. 1

Antiproliferative activity

The in vitro gastrointestinal digests from surimi added without and with antioxidant loaded with βG-V-N were examined for antiproliferative activity against five cancer cell lines including HEK, MCF-7, U87, HeLa, and IMR-32. The samples remarkably inhibited the proliferation of cancer cells, however the C sample showed lower inhibition, than other samples (p < 0.05) for all the cell lines tested. The results indicated that % inhibition ranged from 31 to 54% in all the cell lines (Fig. 4). However, no difference was found in the inhibition ability of surimi digests containing βG-V-N with or without added antioxidants (p > 0.05). MCF-7 cancer cell line was more sensitive to surimi GI digest, resulting in higher % inhibition (41–54%), while U87 was the least sensitive as shown by the lower inhibition (31–38%). This indicated that the sensitivity of cancer cell lines towards surimi digests depended on the cell types. Picot et al. (2006) found that antiproliferative potential of hydrolysates from fish protein was dependent on the cell line investigated. Breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), which is considered highly invasive, was less sensitive to fish protein hydrolysate treatment, compared to MCF-7/6.

The structural characteristics of peptides derived from food including amino acid sequence, composition, overall charge, hydrophobicity, and length regulate their anticancer activity. The interaction between anticancer peptides and the outer leaflets of tumor cell membrane bilayers are enhanced by the presence of hydrophobic amino acids (Chi et al. 2015). The shorter peptides are reported to show stronger anticancer activity due to their higher molecular mobility and diffusivity, thus enhancing interaction with the cancer cell components (Chalamaiah et al. 2018). Chalamaiah et al. (2015) reported that pepsin hydrolysate obtained from rohu egg (roe) showed 65% inhibition of Caco-2 (human colon cancer cell line). Additionally β-glucan also showed antiproliferation of cancer cells. Shah et al. (2015) documented that γ-irradiation treatment of β-glucan resulted in the formation of low molecular weight β-glucan, which had the increased antiproliferative activities against human cancer cell lines (Colo-205, T47D and MCF7). Choromanska et al. (2015) investigated the antitumor activities of low molecular weight β-glucan from oats in two cancer cell lines Me45 and A431. Cancer cell viability was markedly reduced by treatment with low molecular weight β-glucan. With the increasing incubation time and the β-glucan concentration, the cancer cells viability significantly deceased (Choromanska et al. 2015).

Coconut oil contains medium chain saturated fatty acids including lauric acid, capric acid and caprylic acid. Lauric acid (LA) is reported to have anticancer activity. Lauric acid-induced dose-dependent cytotoxicity towards Raw 264.7 (murine macrophages), HCT-15 (human colon cancer), and HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells showing morphological characteristics of apoptosis (Sheela et al. 2019). Lauric acid treatment at 30 and 50 μg/mL was found to downregulate the expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) by 1.33 and 1.58 fold in HCT-15 cells. Downregulation of EGFR might be related to anticancer activity of LA, which resulted in decreased cell viability (Sheela et al. 2019). Lappano et al. (2017) reported that LA promoted formation of stress fibre and upregulate the p21Cip1/WAF1 expression. The former had a crucial role in morphological changes related with apoptotic cell death, while the latter resulted in apoptosis of breast and endometrial cancer cells.

The surimi gel added with βG-V-N provided an effect on antiproliferative potential of the digest and resulted in higher inhibition compared to the control gels. However, the addition of antioxidants had no profound influence on the antiproliferative potential. Therefore, it was postulated that the simulated gastrointestinal digestion of surimi gel resulted in production of bioactive peptides with potential antiproliferative activity, while β-glucan or its fragments also showed the combined impact on antiproliferation activity of digest from surimi gel.

Conclusion

The incorporation of βG-V-N significantly improved the nutraceutical profile of surimi gel when subjected to simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Remarkable improvements in antioxidant, antidiabetic and anticancer activities of the digests were found with the addition of βG-V-N, especially in combination of EGCG. However, ACE-IA was not improved by the addition of βG-V-N. Therefore, incorporation of βG-V-N in conjunction with antioxidant could improve the nutraceutical profile of the surimi gel, in which the functional surimi with improved health benefits could be produced.

Acknowledgements

The first author is thankful to Department of Food Science and Technology, University of Kashmir, India for allowing to use their laboratories. Scholarship given to first author under Thailand’s Education Hub for Southern Region of ASEAN Countries (TEH-AC, 2015) is also acknowledged. Prince of Songkla University (Grant No. AGR6302013N) was acknowledged for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmad M, Mudgil P, Gani A, Hamed F, Masoodi FA, Maqsood S. Nano-encapsulation of catechin in starch nanoparticles: characterization, release behavior and bioactivity retention during simulated in-vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2019;270:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougatef A, Nedjar-Arroume N, Manni L, Ravallec R, Barkia A, Guillochon D, Nasri M. Purification and identification of novel antioxidant peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of sardinelle (Sardinella aurita) by-products proteins. Food Chem. 2010;118:559–565. [Google Scholar]

- Bozbulut R, Sanlier N. Promising effects of β-glucans on glyceamic control in diabetes. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;83:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Chalamaiah M, Jyothirmayi T, Diwan PV, Kumar BD. Antiproliferative, ACE- inhibitory and functional properties of protein hydrolysates from rohu (Labeo rohita) roe (egg) prepared by gastrointestinal proteases. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:8300–8307. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1969-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalamaiah M, Yu W, Wu J. Immunomodulatory and anticancer protein hydrolysates (peptides) from food proteins: a review. Food Chem. 2018;245:205–222. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanarat S, Benjakul S. Impact of transglutaminase on gelling properties of Indian mackerel fish protein isolate. Food Chem. 2013;136:929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanarat S, Benjakul S, H-Kittikun A. Comparative study on protein cross-linking and gel enhancing effect of microbial transglutaminase on surimi from different fish. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:844–852. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi C, Hu F, Wang B, Li T, Ding G. Antioxidant and anticancer peptides from the protein hydrolysate of blood clam (Tegillarca granosa) muscle. J Funct Foods. 2015;15:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Choromanska A, Kulbacka J, Rembialkowska N, Pilat J, Oledzki R, Harasym J, Saczko J. Anticancer properties of low molecular weight oat beta-glucan—an in vitro study. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;80:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang M, Xiong S, Hu Y, Yin T, You J. In vitro pepsin digestion of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) surimi gels after cross-linking by microbial transglutaminase (MTGase) Food Hydrocoll. 2019;95:152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gamez C, Zafra MP, Sanz V, Mazzeo C, Ibanez MD, Sastre J, del Pozo V. Simulated gastrointestinal digestion reduces the allergic reactivity of shrimp extract proteins and tropomyosin. Food Chem. 2015;173:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gani A, Benjakul S. Effect of β-glucan stabilized virgin coconut oil nanoemulsion on properties of croaker surimi gel. J Aquat Food Prod Technol. 2019;28:194–209. [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno PJ, Batista I, Pires C, Bandarra NM, Espejo-Carpio FJ, Guadix A, Guadix EM. Antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates obtained from discarded Mediterranean fish species. Food Res Int. 2014;65:469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Hur SJ, Lim BO, Decker EA, McClements DJ. In vitro human digestion models for food applications. Food Chem. 2011;125:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain PR, Rather SA, Suradkar PP. Structural characterization and evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer and hypoglycemic activity of radiation degraded oat (Avena sativa) β-glucan. Radiat Phys Chem. 2018;144:218–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kardono LBS, Tjahja IP, Artanti N, Manuel J. Isolation, characterization and α- glucosidase inhibitory activity of beta glucan from silver ear mushroom (Tremella fuciformis) J Biol Sci. 2013;13:406–411. [Google Scholar]

- Khantaphant S, Benjakul S, Kishimura H. Antioxidative and ACE inhibitory activities of protein hydrolysates from the muscle of brownstripe red snapper prepared using pyloric caeca and commercial proteases. Process Biochem. 2011;46:318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Ko J-Y, Kang N, Lee J-H, Kim J-S, Kim W-S, Park S-J, Kim Y-T, Jeona Y-J. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from an enzymatic hydrolysate of flounder fish (Paralichthys olivaceus) muscle as a potent anti-hypertensive agent. Process Biochem. 2016;51:535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Lappano R, Sebastiani A, Cirillo F, Rigiracciolo DC, Galli GR, Curcio R, Malaguarnera R, Belfiore A, Cappello AR, Maggiolini M. The lauric acid-activated signalling prompts apoptosis in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017;3:17063. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yu Z, Zhu H, Zhang W, Chen Y. In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of isolated fractions from water extract of Qingzhuan dark tea. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:e378. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1361-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Nakashima S, Nakamura T, Munemasa S, Murata Y, Nakamura Y. (–)–Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits human angiotensin-converting enzyme activity through an autoxidation-dependent mechanism. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2017;31:e21932. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood S, Benjakul S. Comparative studies of four different phenolic compounds on in vitro antioxidative activity and the preventive effect on lipid oxidation of fish oil emulsion and fish mince. Food Chem. 2010;119:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Oki T, Osajima Y. Isolation and identification of peptidic α-Glucosidase inhibitors derived from Sardine muscle hydrolyzate. Z Naturforsch C Biol Sci. 1999;54:259–263. doi: 10.1515/znc-1999-3-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves AC, Harnedy PA, O’Keeffe MB, FitzGerald RJ. Bioactive peptides from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) with angiotensin converting enzyme and dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitory, and antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2017;218:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J-Y, Kim E-A, Lee H, Kim H-S, Lee J-S, Jeon Y-J. Antihypertensive effect of surimi prepared from olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) by angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity and characterization of ACE inhibitory peptides. Process Biochem. 2019;80:164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ovissipour M, Rasco B, Shiroodi SG, Modanlow M, Gholami S, Nemati M. Antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates from whole anchovy sprat (Clupeonella engrauliformis) prepared using endogenous enzymes and commercial proteases. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93:1718–1726. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palozza P, Krinsky NI. β-Carotene and α-tocopherol are synergistic antioxidants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;297:184–187. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90658-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson IAL, Josefsson M, Persson K, Andersson RGG. Tea flavanols inhibit angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and increase nitric oxide production in human endothelial cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58:1139–1144. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.8.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petcharat T, Benjakul S. Effect of gellan incorporation on gel properties of bigeye snapper surimi. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;77:746–753. [Google Scholar]

- Picot L, Bordenave S, Didelot S, Fruitier-Arnaudin I, Sannier F, Thorkelsson G, Berge JP, Guerard F, Chabeaud A, Piot JM. Antiproliferative activity of fish protein hydrolysates on human breast cancer cell lines. Process Biochem. 2006;41:1217–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Quan TH, Benjakul S. Duck egg albumen hydrolysate-epigallocatechin gallate conjugates: antioxidant, emulsifying properties and their use in fish oil emulsion. Colloids Surf A. 2019;579:e123711. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhan AH, Nawas T, Zhang X, Pembe WM, Xia W, Xu Y. Purification and identification of a novel antidiabetic peptide from Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) protein hydrolysate against α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Int J Food Prop. 2017;20:S3360–S3372. [Google Scholar]

- Rohman A, Che Man YB. The use of Fourier transform mid infrared (FT-MIR) spectroscopy for detection and quantification of adulteration in virgin coconut oil. Food Chem. 2011;129:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sae-leaw T, O’Callaghan YC, Benjakul S, O’Brien NM. Antioxidant activities and selected characteristics of gelatin hydrolysates from seabass (Lates calcarifer) skin as affected by production processes. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53:197–208. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senphan T, Benjakul S. Antioxidative activities of hydrolysates from seabass skin prepared using protease. J Funct Foods. 2014;6:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Senphan T, Benjakul S. Comparative study on virgin coconut oil extraction using protease from hepatopancreas of pacific white shrimp and alcalase. J Food Process Preserv. 2017;41:e12771. [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Ahmad M, Ashwar BA, Gani A, Masoodi FA, Wani IA, Wani SM, Gani A. Effect of γ-irradiation on structure and nutraceutical potential of β-D-glucan from barley (Hordeum vulgare) Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:1168–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Gani A, Masoodi FA, Wani SM, Ashwar BA. Structural, rheological and nutraceutical potential of β-glucan from barley and oat. Bioact Carbohydr Diet Fibre. 2017;10:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sheela DL, Narayanankutty A, Nazeem PA, Raghavamenon AC, Muthangaparambi SR. Lauric acid induce cell death in colon cancer cells mediated by the epidermal growth factor receptor downregulation: an in silico and in vitro study. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2019;38:753–761. doi: 10.1177/0960327119839185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Wang X, Chang T, Wang C, Yang H, Cui M. Effects of vegetable oils on gel properties of surimi gels. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2014;57:586–593. [Google Scholar]

- Sinthusamran S, Benjakul S. Physical, rheological and antioxidant properties of gelatin gel as affected by the incorporation of β-glucan. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;79:409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Steel RGD, Torrie JH. Principles and procedures of statistics. A biometrical approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18:321–336. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Liang Q, Chen Q, Xu J, Shi Z, Wang Z, Liu Y, Ma H. Hydrolysis kinetics and radical-scavenging activity of gelatin under simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2014;163:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Li W, Chen Z, Guo Q, Wang C, Santhanam RK, Chen H. Inhibitory effect of Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate on α-glucosidase and its hypoglycemic effect via targeting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;125:605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Ma C-M, Shahidi F. Antioxidant and antiviral activities of lipophilic epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) derivatives. J Funct Foods. 2012;4:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Chen T, Lin H, Chen H, Liu J, Lyu F, Ding Y. Physicochemical properties and microstructure of surimi treated with egg white modified by tea polyphenols. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;90:82–89. [Google Scholar]