Abstract

Native buckwheat starch was extracted and modified by heat-moisture treatment (HMT) with different treatment time (15, 30 and 45 min) to investigate its effect on physicochemical, morphological, functional properties, starch profile (rapidly digestible starch, RDS; slowly digestible starch, SDS and resistant starch, RS fractions) and expected glycemic index (eGI). Results revealed that with increasing time duration of HMT from 15 to 45 min, amylose content, pasting temperature and thermostability increased substantially whereas swelling power, solubility and viscosity parameters decreased. The SEM micrographs showed that HMT caused fissures in the granule and surface indentation. HMT-45 (starch treated for 45 min) had the lowest RDS content (29.33%) and the highest SDS (51.30%) and RS (8.21%) levels. The decreased hydrolysis rate, high amylose and RS content of HMT-45 resulted in a significant decrease in estimated glycemic index (eGI) values from 51.49% (Native) to 44.16% (HMT-45) thus indicating its role in prevention of non-insulin- dependent diabetes.

Keywords: Buckwheat starch, HMT modification, Pasting property, SEM, eGI

Introduction

Presently, buckwheat starch is being used as an ingredient in development of fat replacer, extruded products, nanocomposite material and as a substrate for preparation of alcoholic beverage. Buckwheat starch can be utilized in innovative food and non-food applications. Buckwheat starch lacks gluten to integrate in food network due to which its use in food products is limited. Native starch usage in food applications is limited due to its intrinsic properties such as insolubility in cold water, lower gelatinization temperature, retrogradation and loss of viscosity after cooking. Therefore, native starches can be successfully substituted by modified starches due to their desirable specific functional properties in processed food industries (Sajilata and Singhal 2005).

Starch modification can be carried out by different methods: physical, chemical or enzymatic to widen its application in food and other industries. However, the physical modification is the most pertinent method as it is chemically safe, economical and highly acceptable among people (Rutenberg and Solarek 1984). One of the methods used for physical modification of native starch is the heat-moisture treatment (HMT) which improves various functional properties of starch and expand their usage (Hoover and Manuel 1996). HMT involves treatment of starch granules at moisture levels lower than 35% (w/w) for 15 min to 16 h and at a temperature range that is below gelatinization temperature but higher than the glass transition temperature (Gunaratne and Hoover 2002).

Previous studies showed that the physicochemical properties and in vitro digestibility of both common and tartary buckwheat starch are significantly changed on application of high hydrostatic pressure (HHP), heat-moisture treatment and annealing treatment (Liu et al. 2015, 2016). Liu et al. (2015) reported that amylose content, slowly digested starch, resistant starch increased and peak viscosity value, swelling power, solubility index, total hydrolysis content of common buckwheat starch declined significantly after HMT modification. Liu et al. (2016) stated that after application of HHP amylose content, pasting temperature and thermostability increases whereas swelling power, hardness and viscosity decreased. With increase in pressure treatment, there was a decreased in-vitro hydrolysis, low RDS and increased SDS and RS fractions. But limited research has been done on buckwheat starch especially with regards to the effect of time of HMT on eGI which can help in the development of products for diabetic people, celiac people and other conventional consumers.

The present study was carried out with the objective of starch isolation from buckwheat and to study the effect of treatment time of HMT on physicochemical, morphological, functional, pasting properties, starch profile (RDS, SDS, RS) and eGI of isolated buckwheat starch. In future, the relevant results can be used to extend the usage of buckwheat starch as a potential food ingredient in food industries.

Materials and methods

Buckwheat groats were procured from local market in Mysuru, Karnataka (India) and dust, dirt was removed before use. All the chemicals and reagents used in the study were of analytical grade. Pullulanase enzyme from Bacillus acidopulyicus (Promozyme 400 L) was purchased from Sigma chemical company, USA. RS assay kit was purchased from Megazyme International Ireland Limited, Ireland. Amyloglucosidase, porcine pancreatic α-amylase, heat stable α-amylase were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore, India.

Isolation of starch

The buckwheat starch was isolated from native groats by the alkaline method using 0.02% NaOH solution with slight modifications (Qian et al. 1998). Defatted flour (petroleum ether extraction) was steeped in NaOH solution for overnight. Mixture was blended, passed through US no. 60 (250 µm) sieve and centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 min. Supernatant and protein layer (brown–yellow color) above the starch layer was discarded. The starch sediment was collected and again suspended in distilled water and centrifuged until no protein layer was visible on the surface. The starch cake was dried overnight at 45 °C, homogenized with laboratory scale grinder, sieved to 250 µm and stored for further analysis.

Heat moisture treatment (HMT)

Buckwheat starch at 15% moisture level was equilibrated at 4 °C for 24 h. Starch was then placed in sealed glass tubes, autoclaved at 121 °C for 15, 30 and 45 min, referred as HMT-15, HMT-30 and HMT-45 respectively with slight modifications (Hormdok and Noomhorn 2007). Starches were removed from glass tubes after HMT, dried at 40 °C and then ground.

Physico-chemical properties of starches

Proximate composition of starch samples was determined according to AOAC methods (2012). Amylose content was determined following method described by Sowbhagya and Bhattacharya (1979).

Functional properties

Water binding capacity of the starch samples were determined by the method of Medcalf and Gilles (1965). Starch swelling power and solubility were determined by a method described by Subramanian et al. (1994).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the starch granules was studied using Scanning Electron Microscope (Shimadzu SSX-550). Samples were suspended in acetone (1%) followed by spreading on the surface of the stub and dried in an oven at 32 °C for 24 h. The samples were coated with gold layer and were observed under an acceleration voltage of 15 kV, at magnification of 3000X.

Pasting properties

The pasting properties of native and modified starch were determined by a Rapid Visco Analyser (RVA-4, Newport Scientific, Australia) using a Standard Analysis Profile. Sample of 3.0 g (14% wet basis) was weighed in the RVA canister and 25 mL of distilled water was added to it. The sample was held at 50 °C for 1 min, heated to 95 °C in 7.5 min, held at 95 °C for 5 min and then cooled to 50 °C in 7.5 min. Pasting temperature, peak, breakdown, final and setback viscosity were recorded.

In vitro starch kinetics

The amount of starch fractions based on digestibility was calculated by using the method of Englyst et al. (1992) with minor modifications. The rapidly digestible starch (RDS) was defined as the starch fraction that was hydrolyzed within 20 min incubation and resistant starch (RS) was defined as the fraction that remained unhydrolyzed after 180 min incubation.

The in vitro starch digestion kinetics and expected glycemic index (eGI) was calculated in accordance with the procedure followed by Goni et al. (1997). A first order kinetic equation [C = C∞ (1 − e−kt)] was applied to describe the kinetics of starch hydrolysis, where C, C∞ and k are the hydrolysis degree at each time, the maximum hydrolysis extent after 180 min and the kinetic constant respectively. The hydrolysis index (HI) was calculated as the percentage ratio between the area under the hydrolysis curve (0–3 h) of starch samples and the area under curve of white bread (control).

The eGI was calculated using the equation proposed by Goni et al. (1997): eGI = (0.549 × HI) + 39.71.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicates as Mean ± SD. Tukey’s test at 5% significant level was used to compare means using ANOVA (SPSS, 2002).

Results and discussion

Chemical composition of buckwheat starch

The chemical composition of native and modified buckwheat starch is presented in Table 1. The moisture content of native starch was 12.55% and in the range of 7.31–7.86% for modified starches. With an increase in treatment time of HMT, moisture content in modified starches increases from 7.31 (HMT-15) to 7.86 (HMT-45) which may be due to severe changes in granular structure of starch, more thermostable structure and less loss of water molecules in HMT-45 comparatively. HMT starches had lower moisture content than native starch due to changes in starch granular structure resulting in easy loss of free water molecules (Liu et al. 2015). There was reduction in protein, fat, ash and total starch content of Hmt starches as compared to native starch but there was no significant difference among the values. Liu et al. (2015) also stated that HMT did not affect fat content but there was a significant decrease in protein, ash and total starch content. The reduction in protein content was perhaps due to the association between protein and starch molecules (e.g., via hydrogen, covalent, and ionic bonds) (Adebowale et al. 2009). HMT may have resulted in interactions between lipid and amylose, which limited fat mobility and reduced fat content from 0.17% (Native) to 0.15% (HMT-45). The formation of fat–starch complexes during HMT was responsible for the reduction in total starch content (Liu et al. 2015).

Table 1.

Physico-chemical and functional properties

| Parameters | Native starch | HMT-15 | HMT-30 | HMT-45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 12.55 ± 0.02d | 7.31 ± 0.12a | 7.56 ± 0.05b | 7.86 ± 0.04c |

| Ash (%) | 0.51 ± 0.03a | 0.49 ± 0.02a | 0.47 ± 0.03a | 0.48 ± 0.02a |

| Protein | 0.42 ± 0.01a | 0.41 ± 0.01a | 0.41 ± 0.02a | 0.40 ± 0.01a |

| Fat | 0.165 ± 0.01a | 0.152 ± 0.01a | 0.158 ± 0.01a | 0.149 ± 0.01a |

| Total starch (%) | 89.11 ± 0.16a | 88.94 ± 0.24a | 89.12 ± 0.14a | 88.84 ± 0.28a |

| Total amylose content (%) | 28.05 ± 0.23a | 32.72 ± 0.15b | 33.21 ± 0.16b | 33.73 ± 0.21c |

| Water binding capacity (%) | 138.24 ± 0.21a | 214.67 ± 0.19b | 292.42 ± 0.14c | 344.74 ± 0.18d |

*Values are mean ± SD (n = 3)

*Values with different superscripts in rows differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05)

Amylose content

The amylose content affects physicochemical properties of starches significantly (p ≤ 0.05). Increase in HMT treatment time resulted in increased apparent amylose content of starch from 28.65% (Native) to 33.21% (HMT-45) (Table 1). A similar increase in amylose content was observed in indica rice (Qingjie et al. 2013), maize and potato starch (Miyoshi 2002).

This increase in amylose content was positively correlated with treatment time of HMT which may be due to interaction between amylose–amylopectin and amylose–lipid resulting in limited amylose leaching (Oh et al. 2008). The HMT-stimulated degradation of exterior linear chains amylopectin or interaction between starch chains within the amorphous area of the granule might be another reason for the increase in amylose content (Miyoshi 2002).

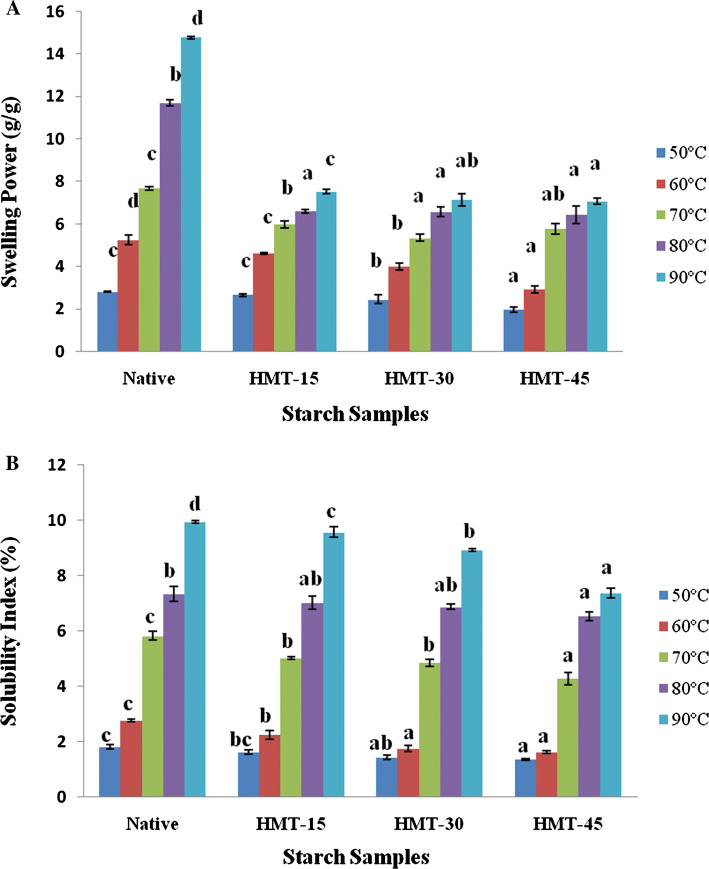

Swelling power and starch solubility index

The swelling power (SP) and solubility index (SI) of native and HMT treated starch are presented in Fig. 1. The interaction between starch chains within the amorphous and crystalline domains can be assessed by SP and SI (Singh et al. 2004). SP and SI values of the native starch were higher than those of the HMT starch at each assay temperature which may be due to structural changes within the starch granule after heat treatment (Leach et al. 1959). With the increment of the assay temperature (50–90 °C), SP and SI of the native and HMT starches were raised correspondingly (Fig. 1) which might be due to weakening of intragranular binding forces and thereby less restricted swelling.

Fig. 1.

Swelling Power (a) and solubility index (b) of starches. *Values with different superscripts at each temperature differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05)

Amylose is contemplated as a diluent and primary amylopectin starch fraction is responsible for swelling power (Hoover 2001). After HMT, the SP of buckwheat starches decreased from 14.75% (Native) to 7.07% (HMT-45) (Fig. 1). Decreasing SP with HMT may be due to rearrangement of molecular chains resulting in restricted water absorption within starch matrix, disruption in crystallite, amylose–lipid interaction (Tester and Morrison 1990), alteration of starch crystallinity and increased interaction between amylose–amylopectin chains (Zavareze and Dias 2011). Due to less amylose leaching in HMT starches, amylose content increases thereby decreasing amylopectin content resulting in less SP. The similar decrease in SP for HMT treated potato, cassava, taro (Gunaratne and Hoover 2002) and rice starches (Hormdok and Noomhorn 2007) has been reported previously.

The amylose which dissociates and diffuses out of the starch granule during swelling results in starch solubility. After HMT, SI also decreased from 9.94 (Native) to 7.37 (HMT-45) g/g at 90 °C (Fig. 1). The decrease of SI during HMT could be due to internal rearrangement of the bonds and higher interactions between amylose and amylopectin molecules, formation of amylose- lipid complexes or highly ordered amylopectin molecules forming a more stable structure, impeding amylose to leach out from the granules (Zavareze and Dias 2011). Similar results were reported in yam and potato starches (Gunaratne and Hoover 2002) and rice starch (Zavareze and Dias 2011).

Water absorption capacity

Water absorption capacity of native and HMT-modified buckwheat starch samples are shown in Table 1. With increasing time for HMT treatment, the WAC increased from 138.24% (Native starch) to 344.74% (HMT-45). Therefore, hydrothermally modified starch will find important applications in food products as thickeners and confectioneries. This result might be attributed to improved hydrophilic tendency of the starch molecules due to disruption of hydrogen bonds between the amorphous and crystalline regions and expansion of the amorphous region during HMT (Adebowale et al. 2009). Similar results were reported by Adebowale et al. (2009) for African yam beans starch and Lorenz and Kulp (1982) in cereals and two tuber starches.

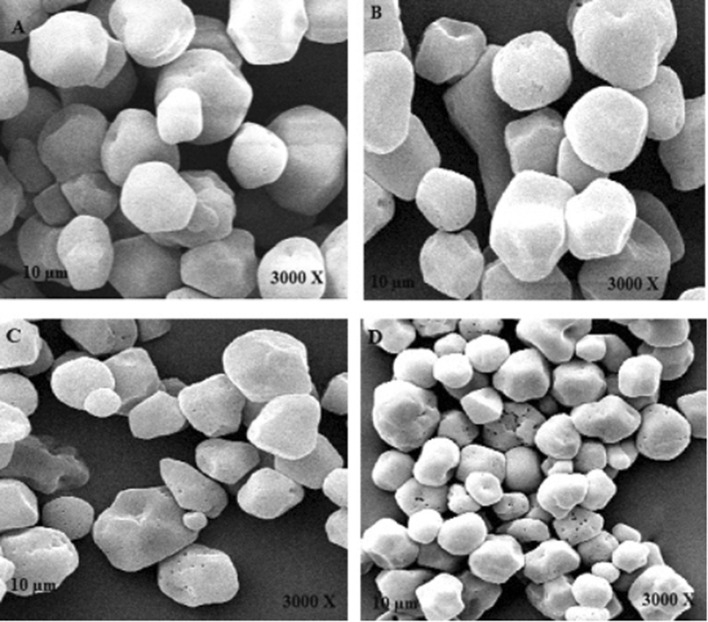

Morphology of starch granules

The morphological characteristics of the starch granules were studied using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Fig. 2). Buckwheat starches micrographs showed the presence of round, polygonal or spherical granules with smooth surface.

Fig. 2.

The scanning electronic micrographs of buckwheat starch: a native starch, b HMT-15, c HMT-30, d HMT-45

The HMT-modified samples had some cavities or fissures on the surface of starch sample. This result was in accordance with the morphological results of HMT treated sorghum and canna starches (Sun et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2010). HMT increased the mobility of starch chains and helical structures due to thermal changes leading to major structural changes in starch granules (BeMiller and Huber 2015).

Granule morphology, size and surface properties plays major role in many food and non-food based utilizations of starch. Fissures in the granule and surface indentation were observed in modified starches which became more pronounced with the increase in treatment time of HMT due to the recombination of amylose and amylopectin chains resulting in compact amorphous regions. Adebowale et al. (2009) and Khunae et al. (2007) also reported insignificant effect in morphology of African yam bean and rice starches after hydrothermal treatment respectively.

Pasting properties

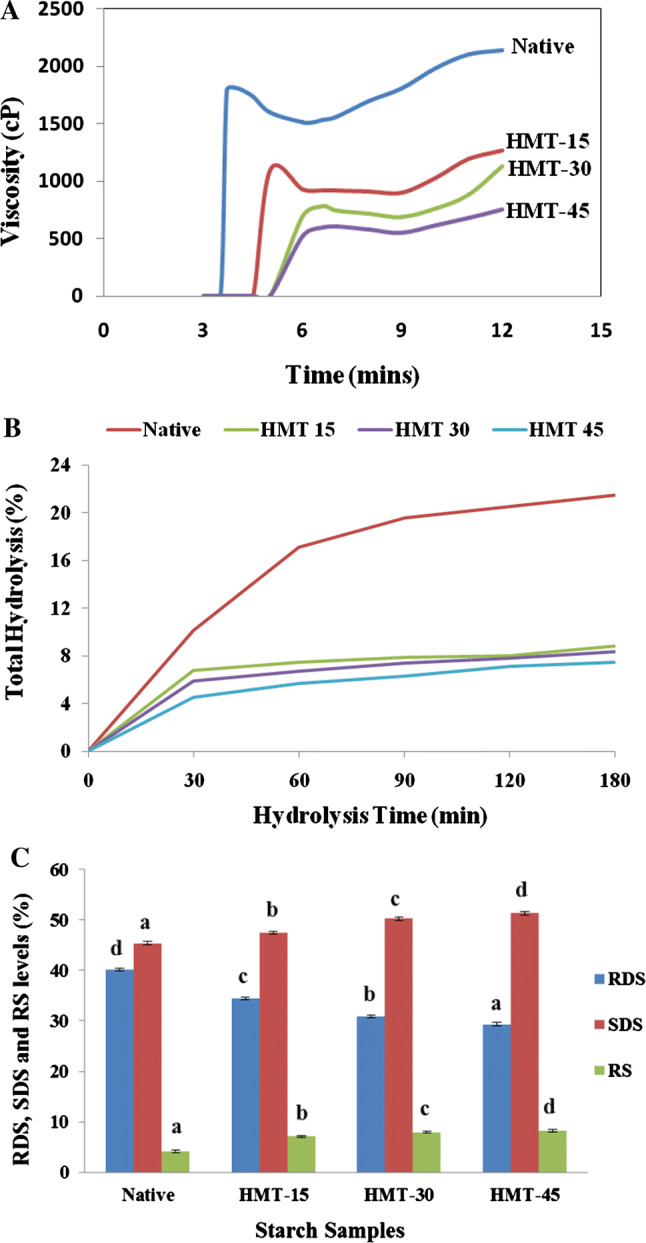

Viscosity of starch is a vital factor for its applicable usage in development of food products with desired consistency. The starch pasting profiles obtained from an RVA could reflect the physico-chemical changes and molecular events occurring in starch during the heating cycle (Majzoobi et al. 2017). Figure 3a represents the RVA curves describing the viscoamylo-behaviour of the starches.

Fig. 3.

The Pasting viscosity profiles (a), in vitro hydrolysis (b) and the RDS, SDS and RS levels (c) of native and HMT-modified buckwheat starch samples. *Bars bearing different letter within same starch fractions are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05)

The pasting temperature of all modified starches increased compared to native starch and the HMT-45 recorded the highest value (84.10 °C) (Table 2). Similar results were reported by Sun et al. (2014) and Jiranuntakul et al. (2011). HMT increased the pasting temperature of buckwheat starch which suggests that a higher heating temperature is required for structural breakdown and paste formation due to strong forces and cross-links within starch granule (Zavareze and Dias 2011). HMT starches with higher pasting temperature correspond to increased gelatinisation temperatures, increased crystallinity, resistance towards swelling and a thermostable structure.

Table 2.

Effect of HMT on pasting properties

| Parameters | Native starch | HMT-15 | HMT-30 | HMT-45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV (RVU) | 1810.15 ± 1.33d | 1095.51 ± 0.41c | 985.25 ± 0.32b | 606.5 ± 0.29a |

| BD (RVU) | 298.32 ± 0.21d | 254.76 ± 0.22c | 38.76 ± 0.22b | 28.5 ± 0.26a |

| FV (RVU) | 2135.02 ± 0.22d | 1269.99 ± 0.45c | 1129.74 ± 0.21b | 749.25 ± 0.15a |

| SB (RVU) | 743.5 ± 0.16d | 399 ± 0.38c | 380.25 ± 0.31b | 171.75 ± 0.35a |

| Pasting temperature (°C) | 71.95 ± 0.15a | 79.85 ± 0.23b | 83.85 ± 0.26c | 84.1 ± 0.17c |

PV, peak viscosity; BD, breakdown viscosity; FV, final viscosity; SB, setback viscosity; PT, pasting temperature

Values are mean ± SD (n = 3)

Values with different superscripts in rows differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05)

On the other hand, increasing HMT time progressively reduced the peak (PV), breakdown (BD), final (FV) and setback (SB) viscosity of HMT samples. The low PV, BD, FV and SV of HMT starches correlate well with their low swelling power in water thereby decreasing amylose leaching to increase the viscosity. The low viscosity of the starches obtained after modification is beneficial for some food applications including soft candy manufacture, weaning foods and other liquid food products (Snow and O’Dea 1981; Hoover 2001).

The highest peak viscosity can be related with its higher swelling power which promotes the hydration of amorphous lamellae. Peak viscosity of native starch was found 1810.15 cP which reduced to a minimum of 606.5 cP (HMT-45) after modification. Rungarun and Athapol (2007) reported that after HMT, decrease in PV is mainly due to the reduced granular swelling of starch and increased molecular binding forces in the starch chains as observed in sweet potato (Tsakama et al. 2011).

Breakdown viscosity is the measure of stability of the cooked starch to disintegrate. The decreased BV of HMT-45 starch indicates the increased stability of starch towards heat and mechanical stress (Palma-Rodriguez et al. 2012; Zavareze and Dias 2011) required in canned foods. Induced decrease in BD may be caused by the low content of leached amylose from rigid and restricted swollen starch granules (Liu et al. 2015).

The reduction in setback (measure of syneresis of starch upon cooling of the cooked starch pastes) viscosity was observed from 743.5 to 171.75 cP (HMT-45). Low SB has an importance for application in confectionery and bakery products, frozen or cold storage foods.

Irrespective of starch’s origin, HMT promotes a decrease in swelling power and amylose leaching and an increase in thermal stability (Zavareze and Dias 2011).

In vitro starch profile

The hydrolysis curves of native and HMT-modified buckwheat starch are presented in Fig. 3b. The levels of RDS, SDS and RS are showed in Fig. 3c. Total hydrolysis increased with prolonged digestion time (0–3 h) in all starch samples. The degree of hydrolysis in HMT-modified samples decreased with increasing treatment time. Following HMT treatment, RDS content decreased considerably, while SDS and RS levels increased. Increase in SDS might be due to the interactions between buckwheat starch and protein or lipids during HMT (Chung et al. 2009). The increase in RS content of HMT-modified buckwheat starch may be due to strong amylose–amylose and amylose–amylopectin interactions. HMT-45 had the lowest RDS content (29.33%) and the highest SDS (51.30%) and RS (8.21%) levels. Higher SDS and RS fractions are relevant to the glycemic index and prevent non-insulin-dependent diabetes (Jenkins et al. 1988). Therefore, HMT-modified buckwheat starch has greater potential in the prevention of chronic diseases as compared with native starch.

Hydrolysis rate ranged from 10 to 30% for buckwheat starch. Digestion kinetics analysis help to better understand the digestibility of substances and physiological characteristics of the gastrointestinal tract, thereby effectively evaluating the nutritional value of different foods. Up to 60 min, hydrolysis rate of the buckwheat starches increased rapidly. After 90 min of hydrolysis, digestibility of the buckwheat starches gradually reached a plateau, indicating that there was a certain amount of amylose starch.

However, at this time, hydrolysis rate of modified starch were still significantly lower than that of native starches (p ≤ 0.05). High levels of RS in modified starch could increase the quality of chyme, promote proliferation of beneficial bacteria and increase the production of short-chain fatty acids in the colon.

HMT reduced the hydrolysis of buckwheat starch and improved the potential health benefits to prevent chronic diseases by lowering RDS content and increasing SDS and RS content.

Hydrolysis kinetics and estimated glycemic index

The in vitro digestion results including equilibrium concentrations (C∞), kinetic constants (k), hydrolysis index (HI), and estimated glycemic index (eGI) are listed in Table 3. The C∞ values of modified starch (8.91–10.79 mmol/l) were lower than those of the unmodified (20.98 mmol/l) starch. The kinetic constants (k), which reflected the rate of hydrolysis, were significantly higher in native starch (0.025 min−1) than the modified starches (0.019–0.023 min−1). It indicates that the modified starches are less susceptible to the digestive enzymes and slowly hydrolyzed than the granular native starches.

Table 3.

In vitro kinetic parameters for native and modified buckwheat starches

| Sample | C∞ (mmol·l−1) | K (min−1) | Calculated HI | eGI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native | 20.98c | 0.025c | 21.46c | 51.49c |

| HMT-15 | 10.79b | 0.023b | 10.71b | 45.59b |

| HMT-30 | 10.32b | 0.023b | 10.24b | 44.33ab |

| HMT-45 | 8.91a | 0.019a | 8.11a | 44.16a |

*Values with different superscript in each column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

*C∞ and k were determined by equation C = C∞ (1 − e−kt)

The hydrolysis index (HI), another parameter related to digestibility, is used for the estimation of the glycemic index (GI). The HI of the starch samples ranged between 8.11 and 21.46. The estimated glycemic index (eGI) based on the HI ranged between 44.16 and 51.49. HMT-45 starch showed 44.16 eGI value which can be used as an ingredient in low GI food formulations. Consequently, the glycemic index, which represents the overall contribution in increasing the blood glucose level, could be decreased by heat moisture treatment of starch.

Conclusion

HMT did not show significant changes in the starch morphology. However, HMT treatment contributed to starch granules with higher amylose content, less smooth surfaces, less swelling power, less solubility index, increased water absorption capacity and higher thermostability as well as pasting temperature. Pasting properties revealed that HMT modified starches were stable during continued heating and shearing which is desirable in buckwheat food products such as noodles, soup and dumplings. Low peak viscosity also makes modified starch suitable to be used in development of soups, weaning foods and other liquid products. The time of HMT process appeared to be critical since it affects the physicochemical, functional and starch digestibility of the modified starch. Increasing the processing time to 45 min resulted in a series of changes from starch granules to starch molecules inside the granules. HMT-45 resulted in increased amylose, RDS and RS levels of starch. Consequently, HMT-45 resulted in a significant decrease in eGI values thus indicating its role in prevention of diabetes and development of low glycemic index food products. HMT can be considered as an effective modification method that is able to improve the stability of starch and thus can be used as a food ingredient in development of low glycemic index foods.

Acknowledgements

The author, Charu Goel acknowledge Department of Science and Technology (DST), Ministry of Science and Technology, India, for awarding doctoral fellowship under the INSPIRE fellowship programme. The authors sincerely thank Director, DFRL for providing all the necessary facilities for carrying out the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adebowale KO, Henle T, Schwarzenbolz U, Doert T. Modification and properties of African yam bean (Sphenostylis stenocarpa Hochst. Ex A. Rich.) Harms starch I: heat moisture treatments and annealing. Food Hydrocoll. 2009;23:1947–1957. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC (2012) Official methods of analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington

- BeMiller JN, Huber KC. Physical modification of food starch functionalities. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2015;6:19–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022814-015552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Liu Q, Hoover R. Impact of annealing and heat-moisture treatment on rapidly digestible, slowly digestible and resistant starch levels in native and gelatinized corn, pea and lentil starches. Carbohydr Polym. 2009;75:436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Englyst HN, Kingman SM, Cummings JH. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992;46:33–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goni I, Garcia-Alonso A, Saura-Calixto F. A starch hydrolysis procedure to estimate glycemic index. Nutr Res. 1997;17:427–437. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(97)00010-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaratne A, Hoover R. Effect of heat-moisture treatment on the structure and physicochemical properties of tuber and root starches. Carbohydr Polym. 2002;49:425–437. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(01)00354-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover R. Composition, molecular structure and physicochemical properties of tuber and root starches—a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2001;45:253–267. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(00)00260-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover R, Manuel H. Effect of heat- moisture treatment on structure and physicochemical properties of legume starches. Food Res Int. 1996;29:731–750. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(97)86873-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hormdok R, Noomhorn A. Hydrothermal treatment of rice starch for improvement of rice noodle quality. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2007;40:1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2006.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins D, Wolever T, Buckley G, Lam K, Giudici S, Kalmusky J. Low glycemic index starchy foods in the diabetic diet. Amer J Clin Nutr. 1988;48(2):248–254. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiranuntakul W, Puttanlek C, Rungsardthong V, Puncha-arnon S, Uttapap D. Microstructural and physicochemical properties of heat-moisture treated waxy and normal starches. J Food Engg. 2011;104:246–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khunae P, Tran T, Sirivongpaisal P. Effect of heat-moisture treatment on structural and thermal properties of rice starches differing in amylose content. Starch–Starke. 2007;59:593–599. doi: 10.1002/star.200700618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leach HW, Mccowen LD, Sohoch TJ. Structure of the starch granule I. Swelling and solubility pattern of various starches. Cereal Chem. 1959;36:534–544. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Guo X, Li W, Wang X, Lv M, Peng Q, Wang M. Changes in physicochemical properties and in vitro digestibility of common buckwheat starch by heat-moisture treatment and annealing. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;132:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Guo X, Li Y, Li H, Fan H, Wang M. In vitro digestibility and changes in physicochemical and textural properties of tartary buckwheat starch under high hydrostatic pressure. J Food Engg. 2016;189:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K, Kulp K. Cereal and root starch modification by heat moisture treatment. I. Physicochemical properties. Starch/Starke. 1982;34:50–54. doi: 10.1002/star.19820340205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majzoobi M, Roushan F, Kadivar M, Farahnaky A, Seifzadeh N. Effects of heat-moisture treatment on physicochemical properties of wheat starch. Iran Agric Res. 2017;36:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Medcalf DG, Gilles KA. Wheat starch. I. Comparison of physicochemical properties. Cereal Chem. 1965;42:558–568. [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi E. Effects of heat-moisture treatment and lipids on gelatinization and retrogradation of maize and potato starches. Cereal Chem. 2002;79:72–77. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2002.79.1.72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HE, Hemar Y, Anema SG, Wong M, Pinder DN. Effect of high-pressure treatment on normal rice and waxy rice starch-in-water suspensions. Carbohydr Polym. 2008;73(2):332–343. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2007.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Rodriguez HM, Agama-Acevedo E, Mendez-Montealvo G, Gonzalez-Soto RA, Vernon-Carter EJ, Bello-Pérez LA. Effect of acid treatment on the physicochemical and structural characteristics of starches from different botanical sources. Starch–Starke. 2012;64:115–125. doi: 10.1002/star.201100081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Rayas-Duarte P, Grant L. Partial characterization of buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) starch. Cereal Chem. 1998;75:365–373. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.1998.75.3.365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qingjie S, Tao W, Liu X, Yunxia Z. The effect of heat moisture treatment on physicochemical properties of early indica rice. Food Chem. 2013;141:853–857. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rungarun H, Athapol N. Hydrothermal treatments of rice starch for improvement of rice noodle quality. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2007;40:1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2006.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutenberg MW, Solarek D. Starch derivatives: production and uses. In: Whistler RL, BeMiller JN, Paschall EF, editors. Starch: chemistry and technology. London: Academic Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sajilata MG, Singhal RS. Specialty starches for snack foods. Carbohydr Polym. 2005;59:131–151. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2004.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Sandhu KS, Kaur M. Characterization of starches separated from Indian chickpea (Cicer arietinum) cultivars. J Food Engg. 2004;63:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2003.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snow P, O’Dea K. Factor affecting the rate of hydrolysis of starch in food. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;43:2721–2727. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.12.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowbhagya CM, Bhattacharya KR. Simplified determination of amylose in milled rice. Starch–Starke. 1979;31:159–163. doi: 10.1002/star.19790310506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V, Hoseney RC, Bramel-Cox P. Shear thinning properties of sorghum and corn starches. Cereal Chem. 1994;71:272–275. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Han Z, Wang L, Xiong L. Physicochemical differences between sorghum starch and sorghum flour modified by heat-moisture treatment. Food Chem. 2014;145:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.08.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester RF, Morrison WR. Swelling and gelatinization of cereal starches. I. Effects of amylopectin, amylase and lipids. Cereal Chem. 1990;67:551–557. [Google Scholar]

- Tsakama M, Mwangwela AM, Manani TA, Mahungu NM. Effect of heat moisture treatment on physicochemical and pasting properties of starch extracted from eleven sweet potato varieties. Int J Agric Sci Soil Sci. 2011;1:254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Zavareze EDR, Dias ARG. Impact of heat-moisture treatment and annealing in starches: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;83:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.08.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Chen F, Liu F, Wang Z. Study on structural changes of microwave heat-moisture treated resistant Canna edulis Ker starch during digestion in vitro. Food Hydrocoll. 2010;24:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]