Abstract

Background

Traditional 2-stage breast reconstruction involves placement of a textured-surface tissue expander (TTE). Recent studies have demonstrated textured surface devices have higher propensity for bacterial contamination and biofilm formation.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of smooth surface tissue expanders (STE) in immediate breast reconstruction.

Methods

The authors retrospectively reviewed consecutive women who underwent STE breast reconstruction from 2016 to 2017 at 3 institutions. Indications and outcomes were evaluated.

Results

A total 112 patients underwent STE reconstruction (75 subpectoral, 37 prepectoral placement), receiving 173 devices and monitored for a mean follow-up of 14.1 months. Demographics of patients included average age of 53 years and average BMI of 27.2 kg/m2, and 18.6% received postmastectomy radiation therapy. Overall complication rates were 15.6% and included mastectomy skin flap necrosis (10.4%), seroma (5.2%), expander malposition (2.9%), and infection requiring intravenous antibiotic therapy (3.5%). Six (3.5%) unplanned reoperations with explantation were reported for 3 infections and 3 patients requesting change of plan with no reconstruction.

Conclusions

STEs represent a safe and efficacious alternative to TTE breast reconstruction with at least equitable outcomes. Technique modification including tab fixation, strict pocket control, postoperative bra support, and suture choice may contribute to observed favorable outcomes and are reviewed. Early results for infection control and explantation rate are encouraging and warrant comparative evaluation for potential superiority over TTEs in a prospective randomized trial.

Level of Evidence: 4

Postmastectomy tissue expansion for breast reconstruction was first pioneered by Radovan in the late 1970s.1 Early reports of immediate tissue expander-assisted reconstructions emphasized the importance of these devices for maintaining the anatomic boundaries of the breast such as the inframammary fold and axillary line during expansion, allowing for improved symmetry overall compared with delayed reconstructions.2 Tissue expander-based reconstruction now has wide acceptance, currently comprising nearly 65% of all breast reconstructions.3,4 Immediate tissue expander reconstruction is deemed reliable, cost effective, and versatile with regard to patient applicability.5-7 Additional advantages of tissue expander staged reconstruction include shorter operative length, faster recovery, and minimization of donor site morbidity.8

Tissue expansion utilizes mechanical stress to stimulate new skin proliferation.9 The process of breast reconstruction with tissue expansion has reported high complication rates between 19% and 48%.10-13 Numerous studies describe complications associated with tissue expanders, including expander displacement, deflation, pain with expansion, hematoma, infection, and compression deformity of the chest wall.14,15

Textured-surface tissue expanders (TTE) were proposed as an alternative to smooth tissue expanders to help mitigate problems of malposition and are the current standard in breast reconstruction.16,17 In the 1990s Francel et al reported a 7.4% to 14% minor complication (infection, skin necrosis, seroma, hematoma) rate using smooth tissue expanders, significantly higher than the complication rate observed in multiple studies using textured tissue expanders.14,18,19 Recent data have shown inconsistencies in complication rates between the 2 groups. In a cumulative meta-analysis, Liu et al reported no difference in results between textured and smooth prostheses, although this did not hold true after enlargement of sample size.20 In a Cochrane review, textured prostheses were associated with worse outcomes than smooth prostheses, although the difference was not statistically significant.21

Since the inception of TTEs in the 1980s, there have been no outcomes studies on smooth surface tissue expanders (STE) for breast reconstruction. The purpose of this article is to provide safety and efficacy data for STE and determine whether they provide a reasonable alternative to textured devices.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed a prospectively maintained database of consecutive patients who underwent STE breast reconstruction from March 2016 to December 2017 at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston Methodist Hospital, and Boca Raton Plastic Surgery performed by 4 surgeons. Demographic information, comorbidities, perioperative data, operative data, and complications were collected for comparison. The primary outcomes evaluated were seroma (clinically appreciable fluid collection requiring drainage), infection (cellulitis requiring antibiotic treatment), delayed wound healing (incision opening greater than 5 mm), mastectomy skin flap necrosis (MSFN, including sloughing, desquamation, and/or full-thickness loss requiring bedside or operative debridement), and malposition defined as device movement adequately significant to require surgical correction at time of exchange. Postoperatively, drains were maintained until the output was <20 to 30 mL/24 h. Intravenous perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis was given to all patients.

Technique Variations

Immediately following mastectomy, tissue expanders were placed in either a prepectoral or partially subpectoral pocket with an acellular dermal matrix support at the surgeon’s discretion (Figure 1). STEs were partially filled with either saline or air at the time of surgery, and air was exchanged to saline at 2 weeks postoperatively. Drains were liberally utilized, consisting of two 10 or 15 French drains placed in the subcutaneous space. At least one and in most cases all suture tabs were fixated to the pectoralis fascia and chest wall using either 3-0 PDS (3 surgeons) or 3-0 Prolene suture (1 surgeon). Intraoperative tissue expander fill was at the discretion of the surgeon, and the amount was the maximal amount of tissue expander fill intraoperatively without placing undue tension on the skin closure. Precise acellular dermal matrix (ADM) pocket control was felt to be an important factor among all surgeons, all patients received postoperative surgical bra support, and patients were instructed to limit activity for 4 weeks.

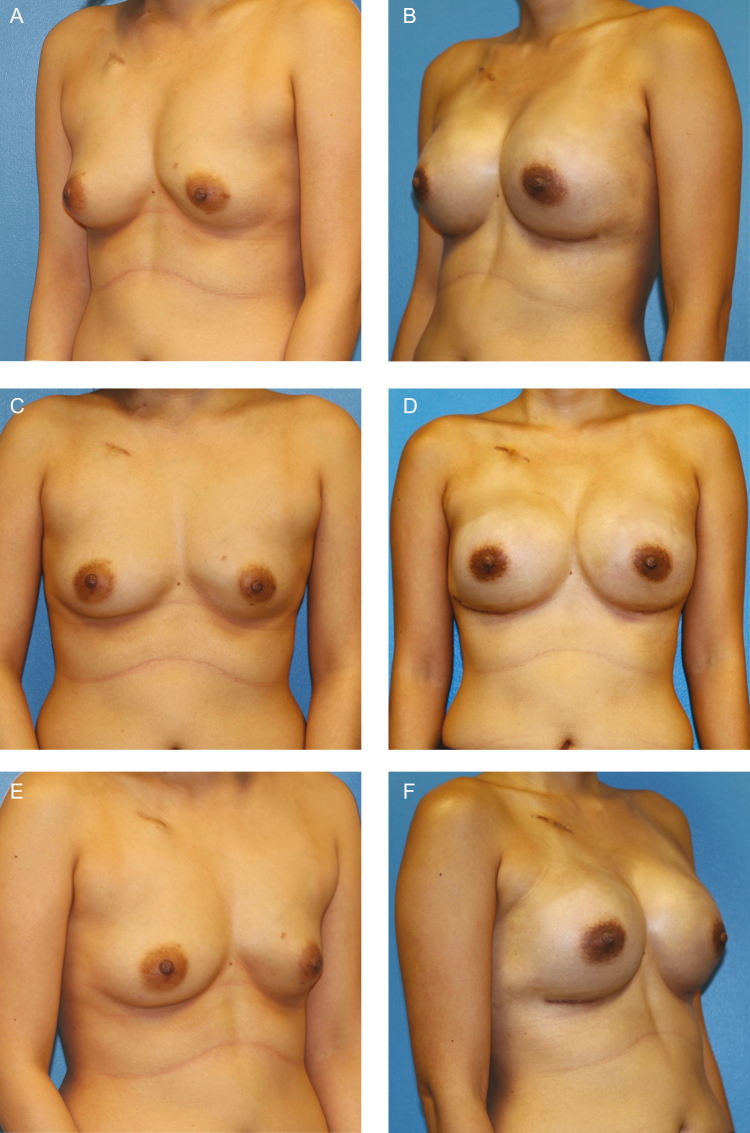

Figure 1.

This patient is a 44-year old woman with left breast invasive ductal carcinoma requiring neoadjuvant chemotherapy, shown (A, C, E) preoperatively and (B, D, F) 1 year postoperatively following exchange to smooth round silicone implants (Inspira SRX 420 cc). (G) Intraoperative appearance of nipple-sparing mastectomy skin flaps and a smooth tissue expander (Artoura 300 cc) (H) with ADM wrap technique for prepectoral placement are demonstrated. (I) Tissue expander was filled with air intraoperatively, which was exchanged to saline at 1 week. Intraoperative view is shown at 3 months following complete expansion prior to exchange.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses were performed in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The timing of complication occurrence between cohorts was compared by means of a 2-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and statistical significance was defined as P < .05. This study was approved and carried out under the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center.

RESULTS

One hundred-twelve patients underwent STE reconstruction divided into 75 (67%) subpectoral and 37 (33%) prepectoral tissue expander placements. Patients received 173 tissue expander devices and were monitored for a mean follow-up of 14.1 months (range, 6-27 months) (Figures 2 and 3). The type of tissue expander employed was 56.3% Artoura Smooth Tissue Expander (Mentor Worldwide LLC, Johnson & Johnson, Irvine, CA) and 43.7% AlloX2 Smooth Tissue Expander with incorporated drainage system (Sientra Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). The average patient age was 53.1 years (range, 28-73 years), average BMI was 27.2 kg/m2 (range, 18.4-43.1 kg/m2), and 18.6% received postmastectomy radiation therapy (Table 1). The type of ADM used was divided: 8% (n = 7) of patients received Flex HD Pliable (Muskuloskeletal Transplant Foundation, Inc., Edison, NJ) and 92% (n = 80) utilized Alloderm RTU Thick (LifeCell Corporation, Bridgewater, NJ). ADM was used in 77.7% (n = 87) of cases overall, and type of mesh used was analyzed against primary outcomes and found to have no influence. Both drains were removed by an average of 16.4 days (range, 4-40 days). Average expander total volume size was 442 mL (range, 300-750 mL). Average intraoperative initial fill volume was 218 mL (range, 0-400 mL) or approximately 49.3% of the tissue expander total volume. Initial expansion was performed on average at 8 days postoperatively (range, 4-19 days). On average, patients received 2.6 expansions (range, 0-4 expansions) 1 week apart, and average time to full expansion was 26 days postoperatively (range, 0-44 days).

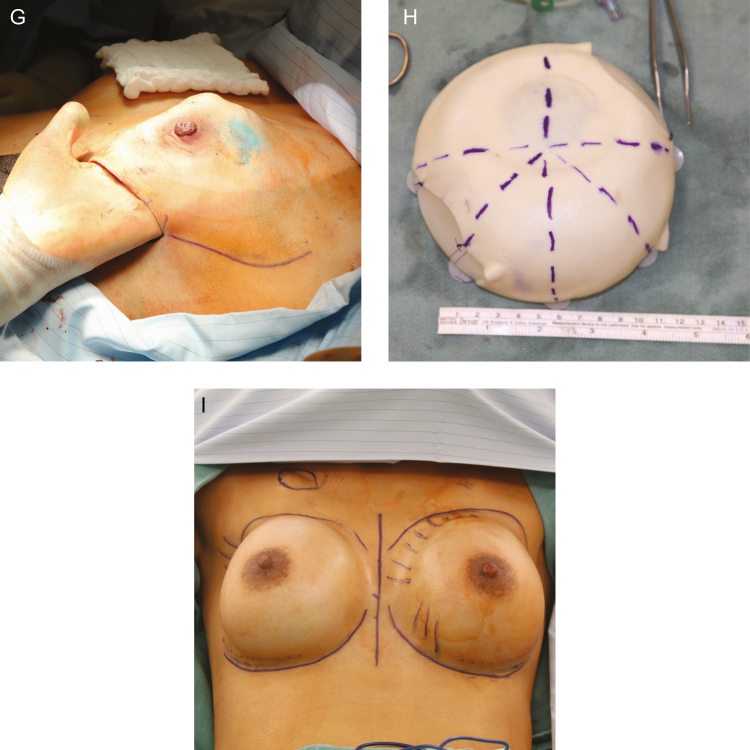

Figure 2.

The intraoperative appearance of a smooth tissue expander with tab fixation and ADM inferolateral sling coverage. (A) Intraoperative appearance of the scar capsule of the smooth tissue expander is demonstrated (B) at 3 months at time of exchange to permanent implant.

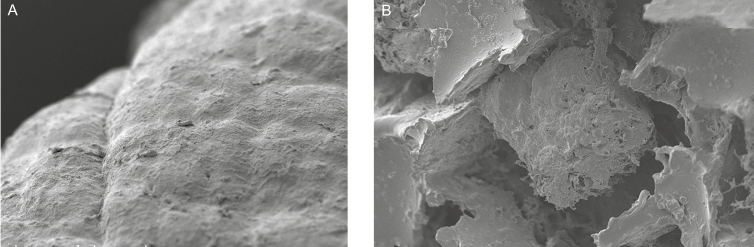

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrographs demonstrating a scar capsule surface from (A, x200 magnification) a smooth tissue expander patient and (B, x200 magnification) a scar capsule surface from a textured-surface tissue expander patient.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic no. | (%)* |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 112 |

| Bilateral reconstruction | 61 (54.5) |

| Unilateral reconstruction | 51 (45.5) |

| No. of tissue expanders | 173 |

| Mean age, y | 53.1 ± 9.5 (range, 28-73) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.2 ± 5.2 (range, 18.4-43.1) |

| BMI | |

| Underweight <20 | 4 (3.6) |

| Normal weight 20-25 | 33 (29.5) |

| Overweight 26-30 | 35 (31.3) |

| Obese class I 31-35 | 29 (25.9) |

| Obese class II 35-40 | 6 (5.4) |

| Obese class III >40 | 5 (4.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 83 (74.1) |

| Hispanic | 14 (12.5) |

| African American | 9 (8.0) |

| Asian/Arabic | 6 (5.4) |

| Smoker | |

| Never | 80 (71.4) |

| Former | 22 (19.6) |

| Active | 10 (8.9) |

| Comorbidity | 25 (22.3) |

| Hypertension | 16 (14.3) |

| Diabetes | 8 (7.1) |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 (1.8) |

| Adjuvant therapy | |

| Preoperative radiotherapy | 5 (4.5) |

| Postoperative radiotherapy | 21 (18.6) |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 32 (28.6) |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 30 (26.8) |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy | 82 (73.2) |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | 16 (14.3) |

| Histologic type | |

| Prophylactic | 19 (17.0) |

| In situ | 17 (15.2) |

| Invasive | 76 (67.9) |

| Histologic class | |

| Ductal | 83 (74.1) |

| Lobular | 6 (5.4) |

| Ductal and lobular | 4 (3.6) |

Although this was not intended as a comparative study, to determine safety and efficacy, a historical control cohort of TTEs was included for review. At a single institution, 957 consecutive patients received 1376 tissue expanders from 2004 to 2014. Patient demographics were comparable to the STE cohort and outcomes are reported in Table 2. Due to the inherent limitations in data acquisition of a historical cohort, data should not be used for any claims of superiority that would require a prospective comparative trial.

Table 2.

Patient Outcomes of Smooth Surface Tissue Expanders

| Characteristic | Smooth surface tissue expanders (n = 173 breasts) | Textured-surface tissue expanders (n = 1376 breasts) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complication | 27 (15.6) | 359 (26.1) | 0.0021 |

| Dehiscence | 4 (2.3) | 55 (4.0) | 0.3971 |

| Hematoma | 0 | 25 (1.8) | 0.1022 |

| Infection | 6 (3.5) | 108 (7.8) | 0.0429 |

| MSFN | 18 (10.4) | 207 (15.0) | 0.1096 |

| Expander malposition | 5 (2.9) | NR | |

| Seroma | 9 (5.2) | 97 (7.0) | 0.427 |

| Explantation | 6 (3.5) | 119 (8.6) | 0.0169 |

MSFN, mastectomy skin flap necrosis; NR, not recorded.

The overall complication rate was 15.6% (n = 27) and included MSFN (10.4%, n = 18), seroma (5.2%, n = 9), expander malposition (2.9%, n = 5), and infection requiring intravenous antibiotic therapy (3.5%, n = 6) (Table 2). Overall complication rates between subpectoral (16.3%) and prepectoral (14.1%) tissue expander (TE) placement were comparable. Of the 6 infections, 2 were salvaged with hospital readmission and intravenous antibiotic according to an institutional red breast protocol.22 One device was salvaged by both intravenous antibiotic administration and percutaneous administration of antibiotic by an integrated drain of the tissue expander (Figure 4). Six (3.5%) patients required unplanned reoperation with explantation. Indication for explantation included 3 (50%) infections and 3 (50%) of the patients requesting change of plan with no reconstruction. Of the 9 (5.2%) seromas, all occurred after the removal of drains. Five seromas occurred with the Mentor Artoura device; of these, 3 required percutaneous aspiration under ultrasound guidance, and 2 seromas were drained at time of exchange to final implant. Four seromas occurred with the Sientra AlloX2 device, and of these, all 4 were drained through the integrated drainage port of the expander. Of the 5 (2.9%) expander malpositions, 4 occurred in the subpectoral plane and 1 occurred in the prepectoral plane. All malpositions were corrected with a combination of capsulectomy and capsulorrhaphy and resulted in no further complications. No devices were found to be ruptured at time of exchange.

Figure 4.

Infection in a smooth tissue expander. This 37-year-old female presented with a gene mutation, for which she desired bilateral prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomies. (A) She underwent immediate breast reconstruction with subpectoral Sientra AlloX2 smooth tissue expanders with Alloderm RTU sling. (B) Two weeks postoperatively, she presented with right breast cellulitis and swelling accompanied with pain, generalized fatigue, and low-grade fever. She was admitted for IV Vancomycin and Cefepime. An integrated drainage port of her tissue expander was used to aspirate a small amount of fluid that later yielded methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Her cellulitis resolved with 48 hours of therapy and she was treated with injection of 20 cc of Vancomycin into her peri prosthetic space via integrated tissue expander drainage port. This was repeated 5 times over the following 2 weeks. Three weeks following her admission to the hospital, her tissue expanders were exchanged for permanent silicone implants, and capsule culture taken at time of exchange was negative for methicillin-resistant S. aureus. (C) She remains without complications at 1 year from last surgery.

DISCUSSION

Tissue expansion is commonly used in breast reconstruction despite reported high overall complication rates.10 The textured surface was designed in the late 1980s to promote tissue ingrowth in an attempt to avoid malposition and disrupt linear fibrosis associated with capsular contracture around traditional smooth-surfaced devices.23 In 1998, Spear et al presented findings of a 7-year investigation evaluating textured tissue expansion, concluding that textured implants carry a relatively lower risk of complication and further propelling the trend towards use of textured implants.19 Our investigation represents the largest outcomes study of smooth surface tissue expanders to determine the safety and efficacy of these devices.

We identified an overall complication rate of 15.6% with the use of smooth surface tissue expanders in a heterogenous patient population. The most common complication was MSFN, which occurred in 10.4% of patients. The rate of MSFN can be a consequence of patient comorbidities such as smoking, obesity, and diabetes, flap devascularization during mastectomy, thermal injury, and skin compromise from overly aggressive intraoperative expansion of a device. Skin necrosis after breast reconstruction with TE may lead to infection or scar contracture, prevent expansion, compromise esthetic outcome, or necessitate removal of the TE. Additionally, MSFN may delay adjuvant therapy and cause significant distress to the patient.24 Previous studies report an incidence of minor skin flap necrosis, full-thickness flap necrosis, and epidermolysis complications in the range of 1.3% to 20%, in line with the findings of this study.25-29

Infection represents one of the most problematic complications of expander-based breast reconstruction, often leading to the most devastating result: loss of the tissue expander.30 While surgical site infections are low in most types of breast surgery, implant-based reconstructions have infection rates as high as 29%,31 often occurring during the expansion phase.32,33 Infection ranges from cellulitis to deep space infection and can cause significant morbidity in addition to greatly increasing healthcare-related costs.29 In our study, 3.5% of patients had surgical site infections necessitating use of IV antibiotics and of these, one-half (1.7%) ultimately required an explantation from the infection. In a study of 1119 prosthetic breast reconstructions, Khavanin and colleagues reported textured implants were associated with higher infection rates than smooth implants (6.1% vs 2.3%; P = 0.002).34 Textured surfaces are independent predictors for infection risk, which may be attributable to the potential for greater bacterial adherence and subsequent biofilm formation on higher surface area devices.35 Within this study, rates of both infection and explantation were low, and this finding merits further investigation to determine if smooth tissue expanders offer superior characteristics to their textured counterparts.

Preoperative radiation therapy was given in 4.5% of patients and postmastectomy radiation in 18.2%. Radiation therapy is an independent risk factor for complications following TE-based reconstruction. Krueger and Cordeiro both reported an increased incidence of complications in irradiated patients.36,37 Additionally, when specifically looking at infection in tissue expanders, radiation has been identified as a risk factor.31 From observations made within this study, radiation delivery did not appear to adversely affect the smooth tissue expander or capsule formation differently when compared to textured tissue expanders. Although the forces of a constricting tissue envelope might be expected to preferentially shift a smooth device, these forces were likely counterbalanced by chest wall fixation with suture tabs.

The effect of a smooth vs textured surface has potential significance for capsule formation, inflammatory mediators, and biocompatibility of a tissue expander. Webb and colleagues demonstrated the propensity for textured surface devices to release particulate shedding and surface debris.38 Textured surface expanders had a different capsular composite than the smooth surface expanders caused by the shed debris. Copeland showed that capsules of textured surfaces have large fragments of silicone in intracellular spaces, vacuolated histiocytes, exuberant reactive synovial metaplasia, and foreign body granulomas in contrast to smooth surface devices.39 The long-term effect and inflammatory significance of wear debris remain the subject of ongoing research. Additionally, device wrapping with acellular dermal matrix during breast reconstruction likely minimizes any benefits of surface texturing and therefore may justify avoiding any associated risks.

Several ways to decrease risk and improve outcomes with TE-based reconstruction have been proposed, including use of ADM and suture tabs. ADM provides increased strength, promotes rapid vascular ingrowth, and serves as a scaffold for new tissue formation.40 ADM has been reported to improve aesthetic outcomes by providing better control of the mastectomy space, optimizing implant positioning; allow for increased intraoperative expansion; and prevent superior migration of the implant.41 Additional potential benefits include reduction of postoperative pain and decreased operative time.42 We have trended towards increased use of ADM because in our practice we find the benefits are broad with a minor increase in complications such as seroma and infection. Potential drawbacks include high cost, which may be outweighed by favorable outcomes.43,44 Use of tabbed tissue expanders improves breast symmetry and minimizes malposition in TE-based breast reconstruction compared with nontabbed TEs.45,46

The current study has several limitations, including the shortcomings inherent to a retrospective design. The sample size may not be sufficient to capture rare events. For example, the decreased rate of MSFN was likely not related to the surface characteristics of the expander but may have been related to changes in management of other risk factors identified, such as a practice shift to filling expanders with air in the immediate postoperative period to decrease skin tension. The significantly lower rate of infection observed with STEs could be related to lower bacterial colonization to the smooth surface or to other technique changes happening concurrently such as lower MSFN. This study was intended to report the safety and efficacy of STE in immediate breast reconstruction, and any determination of superiority over historical controls of TTE is not possible and should not be claimed.

CONCLUSIONS

There was no increased rate of complications with STEs in our cohort compared to previously published reports and our institutional experience with textured expanders. STEs are an acceptable and possibly beneficial alternative for immediate 2-stage breast reconstruction. Technique modification including tab fixation, precise ADM pocket control, postoperative bra support, and suture choice may contribute to observed favorable outcomes. Early results for infection control and explantation warrant comparative evaluation prospective trials.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

Data analyses were supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI Grant P30 CA016672).

REFERENCES

- 1. Radovan C. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy using the temporary expander. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(2):195-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Radovan C. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy using the temporary expander. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(2):195-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bertozzi N, Pesce M, Santi P, Raposio E. Tissue expansion for breast reconstruction: methods and techniques. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;21:34-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fischer JP, Nelson JA, Au A, Tuggle CT III, Serletti JM, Wu LC. Complications and morbidity following breast reconstruction-a review of 16,063 cases from the 2005-2010 NSQIP datasets. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48(2):104-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baschnagel AM, Shah C, Wilkinson JB, Dekhne N, Arthur DW, Vicini FA. Failure rate and cosmesis of immediate tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction after postmastectomy irradiation. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12(6):428-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCarthy CM, Mehrara BJ, Riedel E, et al. Predicting complications following expander/implant breast reconstruction: an outcomes analysis based on preoperative clinical risk. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(6):1886-1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cordeiro PG, McCarthy CM. A single surgeon’s 12-year experience with tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction: part I. A prospective analysis of early complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(4):825e831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaikh-Naidu N, Preminger BA, Rogers K, Messina P, Gayle LB. Determinants of aesthetic satisfaction following TRAM and implant breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(5):465-470; discussion 470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elshahat A. Management of burn deformities using tissue expanders: a retrospective comparative analysis between tissue expansion in limb and non-limb sites. Burns. 2011;37(3):490-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smolle C, Tuca A, Wurzer P, et al. Complications in tissue expansion: a logistic regression analysis for risk factors. Burns. 2017;S0305-4179(16)30335-30337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Handschel J, Schultz S, Depprich RA, et al. Tissue expanders for soft tissue reconstruction in the head and neck area-requirements and limitations. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(2):573-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fochtmann A, Keck M, Mittlböck M, Rath T. Tissue expansion for correction of scars due to burn and other causes: a retrospective comparative study of various complications. Burns. 2013;39(5):984-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Casanova D, Bali D, Bardot J, Legre R, Magalon G. Tissue expansion of the lower limb: complications in a cohort of 103 cases. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54(4):310-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maxwell GP, Falcone PA. Eighty-four consecutive breast reconstructions using a textured silicone tissue expander. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89(6):1022-1034; discussion 1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Slavin SA, Colen SR. Sixty consecutive breast reconstructions with the inflatable expander: a critical appraisal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86(5):910-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nava MB, Catanuto G, Pennati A, et al. Expander-implants breast reconstruction. In Neligan PEC, ed. Plastic Surgery. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Ltd.; 2013:336-369. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spear SL, Pelletiere CV. Immediate breast reconstruction in two stages using textured, integrated-valve tissue expanders and breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):2098-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Francel TJ, Ryan JJ, Manson PN. Breast reconstruction utilizing implants: a local experience and comparison of three techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92(5):786-794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spear SL, Majidian A. Immediate breast reconstruction in two stages using textured, integrated-valve tissue expanders and breast implants: a retrospective review of 171 consecutive breast reconstructions from 1989 to 1996. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(1):53-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu X, Zhou L, Pan F, Gao Y, Yuan X, Fan D. Comparison of the postoperative incidence rate of capsular contracture among different breast implants: a cumulative meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rocco N, Rispoli C, Moja L, et al. Different types of implants for reconstructive breast surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD010895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viola GM, Selber JC, Crosby M, et al. Salvaging the infected breast tissue expander: a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(6):e732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O’Shaughnessy K. Evolution and update on current devices for prosthetic breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2015;4(2):97-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gorai K, Inoue K, Saegusa N, et al. Prediction of skin necrosis after mastectomy for breast cancer using indocyanine green angiography imaging. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5(4):e1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pinsolle V, Grinfeder C, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Faucher A. Complications analysis of 266 immediate breast reconstructions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(10):1017-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zienowicz RJ, Karacaoglu E. Implant-based breast reconstruction with allograft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(2):373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Margulies AG, Hochberg J, Kepple J, Henry-Tillman RS, Westbrook K, Klimberg VS. Total skin-sparing mastectomy without preservation of the nipple-areola complex. Am J Surg. 2005;190(6):907-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salzberg CA. Nonexpansive immediate breast reconstruction using human acellular tissue matrix graft (AlloDerm). Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(1):1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crespo LD, Eberlein TJ, O’Connor N, Hergrueter CA, Pribaz JJ, Eriksson E. Postmastectomy complications in breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;32(5):452-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klein GM, Phillips BT, Dagum AB, Bui DT, Khan SU. Infectious loss of tissue expanders in breast reconstruction: are we treating the right organisms?Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(2):149-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Francis SH, Ruberg RL, Stevenson KB, et al. Independent risk factors for infection in tissue expander breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(6):1790-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kato H, Nakagami G, Iwahira Y, et al. Risk factors and risk scoring tool for infection during tissue expansion in tissue expander and implant breast reconstruction. Breast J. 2013;19(6):618-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hvilsom GB, Friis S, Frederiksen K, et al. The clinical course of immediate breast implant reconstruction after breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(7):1045-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khavanin N, Clemens MW, Pusic AL, et al. Shaped versus round implants in breast reconstruction: a multi-institutional comparison of surgical and patient-reported outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(5):1063-1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jacombs A, Tahir S, Hu H, et al. In vitro and in vivo investigation of the influence of implant surface on the formation of bacterial biofilm in mammary implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(4):471e-480e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krueger EA, Wilkins EG, Strawderman M, et al. Complications and patient satisfaction following expander/implant breast reconstruction with and without radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49(3):713-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL, Disa JJ, McCormick B, VanZee K. Irradiation after immediate tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction: outcomes, complications, aesthetic results, and satisfaction among 156 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(3):877-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Webb LH, Aime VL, Do A, Mossman K, Mahabir RC. Textured breast implants: a closer look at the surface debris under the microscope. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2017;25(3):179-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Copeland M, Choi M, Bleiweiss IJ. Silicone breakdown and capsular synovial metaplasia in textured-wall saline breast prostheses. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94(5):628-633; discussion 634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. JoAnna Nguyen T, Carey JN, Wong AK. Use of human acellular dermal matrix in implant- based breast reconstruction: evaluating the evidence. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(12):1553-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nahabedian MY. Acellular dermal matrices in primary breast reconstruction: principles, concepts, and indications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(5 Suppl 2):44S-53S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ho G, Nguyen TJ, Shahabi A, Hwang BH, Chan LS, Wong AK. A systematic review and meta-analysis of complications associated with acellular dermal matrix-assisted breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68(4):346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hartzell TL, Taghinia AH, Chang J, Lin SJ, Slavin SA. The use of human acellular dermal matrix for the correction of secondary deformities after breast augmentation: results and costs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1711-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ibrahim AM, Koolen PG, Ashraf AA, et al. Acellular dermal matrix in reconstructive breast surgery: survey of current practice among plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3(4):e381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Khavanin N, Gust MJ, Grant DW, Nguyen KT, Kim JY. Tabbed tissue expanders improve breast symmetry scores in breast reconstruction. Arch Plast Surg. 2014;41(1):57-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gust MJ, Nguyen KT, Hirsch EM, et al. Use of the tabbed expander in latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2013;47(2):126-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]