Summary

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection can cause severe bronchiolitis in infants requiring hospitalization, whereas the elderly and immunocompromised are prone to RSV-induced pneumonia. RSV primarily infects lung epithelial cells. Given that no vaccine against RSV is currently available, we tested the ability of the epithelial-barrier protective cytokine interleukin-22 (IL-22) to control RSV production. When used in a therapeutic modality, IL-22 efficiently blunted RSV production from infected human airway and alveolar epithelial cells and IL-22 administration drastically reduced virus titer in the lungs of infected newborn mice. RSV infection resulted in increased expression of LC3B, a key component of the cellular autophagic machinery, and knockdown of LC3B ablated virus production. RSV subverted LC3B with evidence of co-localization and caused a significant reduction in autophagic flux, both reversed by IL-22 treatment. Our findings inform a previously unrecognized anti-viral effect of IL-22 that can be harnessed to prevent RSV-induced severe respiratory disease.

Subject Areas: Immunology, Virology, Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

RSV infection of lung epithelial cells subverts the cellular autophagic machinery

-

•

RSV infection inhibits autophagic flux in infected cells

-

•

IL-22 inhibits RSV production from human lung epithelial cells and in neonatal mice

-

•

IL-22 blocks RSV-LC3B co-localization and restores cellular autophagic flux

Immunology; Virology; Cell Biology

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection can cause severe bronchiolitis in infants, often requiring hospitalization. RSV infection is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in early life worldwide, and the elderly and immunocompromised patients are at high risk for RSV-induced pneumonia (Collins and Graham, 2008; Falsey et al., 2005; Geoghegan et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2007; Mazur et al., 2015; Meissner, 2016; Nair et al., 2010; Openshaw et al., 2017; PrabhuDas et al., 2011; Rezaee et al., 2017). RSV primarily infects lung epithelial cells, which includes both proximal and distal airways as well as alveolar epithelial cells (Bueno et al., 2011; Das et al., 2017; Fonceca et al., 2012; Holtzman et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2007; Liesman et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2008; Openshaw et al., 2017; Schwarze and Mackenzie, 2013). The infection is often characterized by epithelial sloughing, thick mucus secretion, and neutrophil infiltration (Hall, 2001; Liesman et al., 2014; McNamara et al., 2004; Openshaw et al., 2017; Pickles and DeVincenzo, 2015). Currently, no effective vaccine is available against RSV infection, and passive immunoprophylaxis using RSV-specific antibodies is expensive and only used in high-risk subjects (Abarca et al., 2009; Rezaee et al., 2017; Smart et al., 2010). Therefore, alternative strategies are needed to defend against this common pathogen.

Interleukin-22 (IL-22), a cytokine belonging to the IL-10 family, is produced by γδ T cells, T helper (Th) 17 cells, NKT cells, and innate lymphoid cells (ILC2, ILC3) (Sonnenberg et al., 2011). IL-22 primarily acts on non-hematopoietic epithelial and stromal cells and plays a critical role in protecting mucosal epithelial-barrier functions and promoting tissue regeneration along with host defense against various pathogens (Aujla et al., 2008; Brand et al., 2006; Dudakov et al., 2015; Pociask et al., 2013; Sugimoto et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2019). Indeed, the protective role of IL-22 in bacterial and fungal infections is well documented (Aujla et al., 2008; Sugimoto et al., 2008), although its function in the context of viral infections is not uniformly beneficial.

IL-22 has been shown to regulate rotavirus infection in synergy with IL-18 (Zhang et al., 2014) or interferon (IFN)-λ (Hernandez et al., 2015). IL-22 plays a protective role during murine cytomegalovirus infection by coordinating anti-viral neutrophil infiltration into the infected tissue via induction of neutrophil-recruiting CXCL1 (Stacey et al., 2014). Loss of IL-22-producing CD4+ T cells during chronic HIV infection has been associated with increased damage to the gut epithelium associated with increased microbial translocation (Kim et al., 2012). In addition to restricting viral replication, IL-22 has been reported to provide protection against virus-induced pathology in reducing tissue damage and inflammation (Feng et al., 2012; Guabiraba et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2014; Ivanov et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2013; Pellegrini et al., 2011; Pociask et al., 2013). However, in certain contexts, IL-22 has been shown to have detrimental effects during virus infection leading to exacerbated pathology, enhanced inflammation, tissue damage, and mortality (Wang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011). Moreover, increased levels of IL-22 in serum samples indicate poor prognosis for patients with HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (Waidmann et al., 2014). Therefore the effect of IL-22 on virus infection may depend on cellular and tissue contexts, as also the specific pathogen.

In a previous study, IL-22-deficient mice were found to exhibit exacerbated lung injury with impaired lung function compared with wild-type mice suggesting that IL-22 plays a protective role and promotes tissue repair in response to influenza infection (Pociask et al., 2013). Taken together, although various studies showed that IL-22 has epithelial-protective effects in mucosal tissue, given that there is limited information about the effect of IL-22 on RSV production in lung epithelial cells or in the lung, we tested the possibility that use of exogenous IL-22 as a treatment modality would limit RSV production, offering a novel approach to restrict this virus for which no vaccine is currently available. Here we show the ability of IL-22 to suppress RSV production in primary human airway epithelial cells (AECs) and in vivo in newborn mice. Our findings establish a previously unrecognized anti-viral effect of IL-22 that restores cellular autophagy.

Results

Interleukin-22 (IL-22) Inhibits RSV Production in Human Airway Epithelial Cells and Mouse Lungs

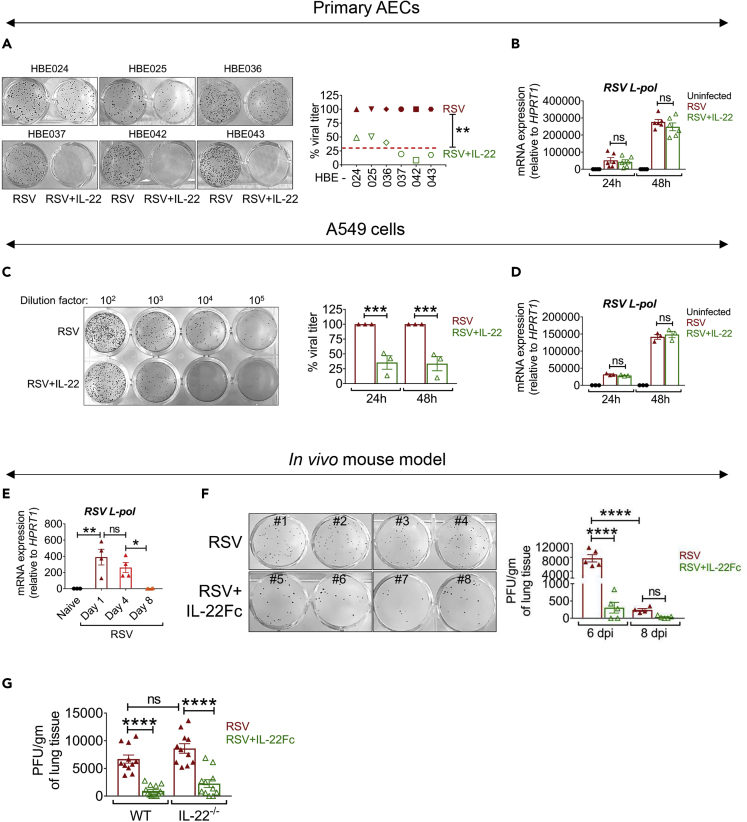

To study the effect of IL-22 on virus production, primary human AECs established in air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures were infected with RSV line 19 strain (denoted here as RSV) (Lukacs et al., 2006) and treated with or without recombinant human IL-22 (rhIL-22; denoted here as IL-22). We observed a 50%–80% reduction in viral plaque formation 48 h after IL-22-treatment of ALI cultures established from six independent subjects (Figure 1A). We next asked whether IL-22 impacted the life cycle of the virus early after infection. As expression of the L-polymerase gene of RSV was similar in both the IL-22-treated and IL-22-untreated groups at 24 and 48 h after RSV infection (Figure 1B), IL-22 did not appear to inhibit the ability of RSV to initiate early events required for its replication. IL-22 functions through a heterodimeric transmembrane receptor complex, which includes IL-22RA1 and IL-10RB (Kotenko et al., 2001). The expression of the IL-22RA1 chain has been associated with IL-22 activity on the target cell (Jones et al., 2008; Wolk et al., 2010). We observed that steady-state mRNA levels of both IL22RA1 and IL10RB were similar across the different primary AECs and remained unaltered after RSV infection or IL-22 treatment at different time points (Figure S1A) suggesting that the expression of the receptor subunits was similar in the established AECs. Similar to investigations of the effect of IL-22 on virus production in primary AECs, we also studied the effect of IL-22 on other RSV-infected epithelial cell lines, including A549. In line with the data derived from primary AECs, RSV viral load decreased after IL-22 treatment of A549 (Figure 1C) cells, with the cells showing unaltered RSV L-polymerase mRNA expression (Figure 1D). At the same time, expression of the IL-22 receptor subunits did not change after RSV infection or IL-22 treatment of A549 cells as observed in the case of primary AECs (Figure S1B).

Figure 1.

IL-22 Inhibits RSV Production in Human Airway Epithelial Cells and Mouse Lungs

(A) Representative viral plaques (left) generated from RSV-infected primary AECs from six independent subjects. At 2 h after infection with RSV (MOI of 1), the cells were treated with rh IL-22 (50 ng/mL) or left untreated and virus was detected by plaque assay using NY3.2 STAT1−/− fibroblast cells. Percent viral titer (right) shown for the six independent primary AEC samples. The red line represents average viral titer in response to IL-22. Viral load with RSV alone considered as 100%. ∗∗p < 0.01.

(B) RSV-L polymerase expression in primary AECs of the human subjects measured by quantitative RT-PCR at 24 and 48 h after RSV infection ± IL-22 treatment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of six independent subjects. ns, non-significant.

(C) Representative viral plaques (left) generated from A549 cells infected with RSV ± IL-22 at 24 h p.i., detected by plaque assay using NY3.2 STAT1−/− fibroblast cells. Infection and IL-22 treatment was as described for primary AECs. Quantitation shown in percentages (right), where viral titer for RSV alone is considered as 100% for each individual experiment at each time point. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) RSV-L polymerase expression in A549 cells measured by quantitative RT-PCR at 24 and 48 h after RSV infection ± IL-22 treatment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ns, non-significant.

(E) RSV-L polymerase expression in total lungs of neonatal mice measured by quantitative RT-PCR on days 1, 4, and 8 after RSV infection. Representative data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, n = 3–4 mice per group per experiment. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ns, non-significant.

(F) Representative viral plaques (left) and quantitated viral load (right) in total lungs of 5-day-old neonatal mice. Infected pups were treated i.p. with 5 μg IL-22Fc fusion protein on day 3 p.i. The lungs were harvested on days 6 and 8 p.i. to assay viral load by plaque assay using Vero cells. Representative data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, n = 4–5 mice per group per experiment. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, non-significant.

(G) Quantitative viral load in the lungs of 5-day-old neonatal mice (wild-type and IL-22−/−). Infected pups were treated i.p. with 5 μg IL-22Fc fusion protein on day 3 p.i. The lungs were harvested on day 6 p.i. to assay viral load by plaque assay using Vero cells. Data shown are mean ± SEM pooled from 3 independent experiments, n = 3–5 mice per group per experiment. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, non-significant.

For statistical analysis, groups were compared using Mann-Whitney test (A) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test (B–G). See Figures S1 and S2.

The cytokine IL-17A can regulate IL-22 function through common downstream pathways (Sonnenberg et al., 2010). Therefore, we examined whether IL-17A rendered a similar anti-viral response against RSV in A549 cells. Interestingly, unlike IL-22, IL-17A was unable to suppress virus production in A549 cells. However, IL-22 and IL-17A co-treatment suppressed viral production by approximately 60%, similar to IL-22 treatment alone (Figure S1C), showing that the anti-viral response by IL-22 against RSV is unaltered by, and independent of, the IL-17A response. We also asked whether the effect of IL-22 in suppressing RSV production was broadly applicable to various RSV strains. We thus examined the effect of IL-22 against infection by RSV 2-20, a more virulent and pathogenic strain than RSV Line-19 (Stokes et al., 2013), and found that IL-22 treatment also significantly suppressed RSV 2-20 virus production in both primary AECs and A549 cells (Figures S1D and S1E), providing further evidence to support that IL-22 inhibits RSV production independent of viral strain and virulence.

Having found this effect of IL-22 on RSV infection of AECs occurs in in vitro settings, we next examined whether IL-22 treatment could decrease RSV production in vivo by treating neonatal RSV-infected mice intraperitoneally (i.p.) with human IL-22Fc fusion protein. The half-life of IL-22Fc in mice is about 107 h (Figure S2A). Also, as expected, whereas treatment with human IL-22Fc did not augment endogenous mouse Il22 expression, it promoted expression of its target gene, Reg3g (Zheng et al., 2008), in the small intestine of the mice demonstrating an expected functional outcome of IL-22Fc treatment (Figures S2B and S2C). IgG used as a control did not induce this effect (Figure S2B). As shown in Figure 1E, the time course of RSV L-polymerase gene expression in mouse lungs showed continued increase until day 4 post-infection (p.i.) with decrease thereafter until day 8, most likely due to gradual viral clearance. Also, our immunostaining data suggested that the peak of the viral titer is reached within 4–6 days after infection (not shown). Taking these observations into consideration, i.p. IL-22Fc treatment was initiated on day 3 p.i. and the viral load was assayed twice on days 6 and 8 after infection. As control IgG did not display effects similar to IL-22 (Figure S2B), we used PBS as a control in these experiments. As shown in Figure 1F, IL-22Fc treatment significantly decreased RSV titer in the lungs of the newborn mice on day 6 p.i. and it also did not render a delayed peak of viral load due to the treatment as suggested from the viral titer on day 8 p.i. We also examined the impact of IL-22Fc on viral infection in the absence of endogenous IL-22 using IL-22−/− mice. The results showed similar viral load in RSV-infected wild-type and IL-22−/− mice and also similar response to IL-22Fc treatment in the two groups (Figure 1G). These data suggest that endogenous IL-22 does not play a role in limiting virus production but that IL-22 can be used as a treatment modality to reduce viral load. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest a potential anti-viral role of IL-22 in the context of RSV infection both in vitro and in vivo.

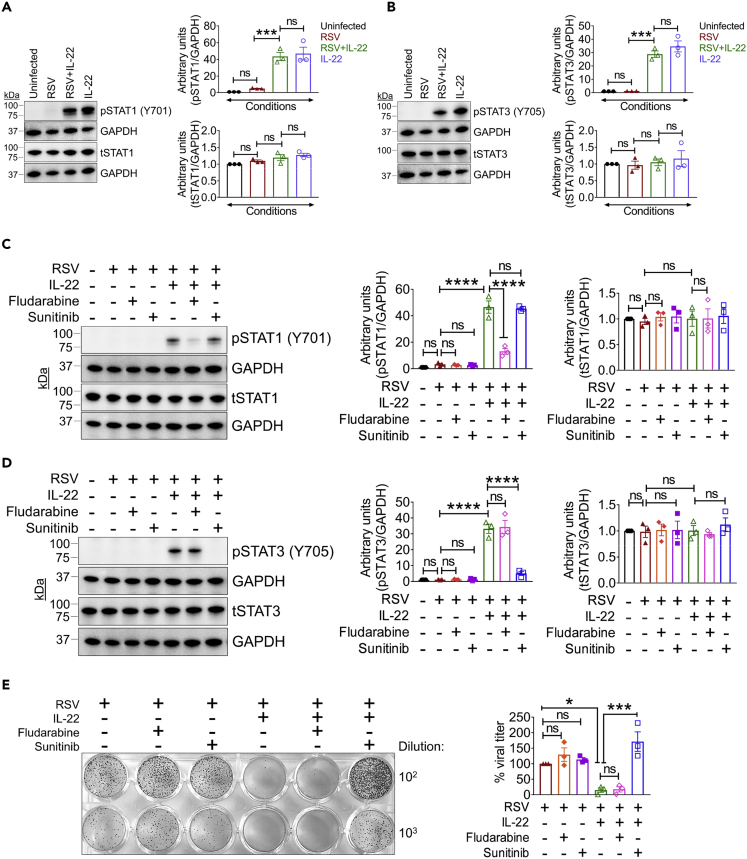

IL-22 Prevents RSV Production through STAT3 Activation

Downstream of IL-22 signaling, IL-22 primarily activates STAT3 (Baturcam et al., 2019; Edsbacker et al., 2019; Gimeno Brias et al., 2016; Mahony et al., 2017; Wolk et al., 2010) with STAT1 involvement in certain instances (Lejeune et al., 2002). To determine which of these pathways is involved in the inhibition of virus production by IL-22, we examined STAT1 and STAT3 activation status in the IL-22-treated A549 cells and observed that IL-22 triggered phosphorylation of both STAT1 and STAT3 to similar degrees (Figures 2A and 2B). To next determine which STAT pathway was necessary for the inhibitory effect of IL-22 on RSV production, we treated RSV-infected cells with the STAT1- and STAT3-specific inhibitors fludarabine and sunitinib, respectively (Figures 2C and 2D), in the presence or absence of IL-22. Blockade of STAT1 with fludarabine had no effect on the anti-viral effect of IL-22, whereas blocking STAT3 activation with sunitinib reversed the inhibitory effects of IL-22 (Figure 2E). Also, both inhibitors were ineffective in the absence of IL-22 (Figure 2E). These results collectively suggested that IL-22 suppresses RSV production through a downstream mechanism mediated by STAT3 activation.

Figure 2.

IL-22 Inhibits RSV Production through STAT3 Activation, Independent of Downstream Interferon Signaling

(A and B) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantitation (right) of (A) phospho-STAT1 (pSTAT1) and total-STAT1 (tSTAT1) and (B) phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3) and total-STAT3 (tSTAT3) in A549 cells after RSV infection and 15 min post IL-22 treatment to detect STAT activation. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ns, non-significant.

(C and D) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantitation (right) of (C) pSTAT1 and tSTAT1 and (D) pSTAT3 and tSTAT3 in A549 cells infected with RSV ± IL-22 and treated with or without fludarabine or sunitinib at 15 min post IL-22 treatment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, non-significant.

(E) Representative viral plaques (left) generated from A549 cells infected with RSV ± IL-22 and treated with/without STAT inhibitors, fludarabine, or sunitinib at 24 h p.i. As described in legend to Figure 1, IL-22 was added 2 h after infection of cells. Quantitation shown in percentages (right), where viral titer for RSV alone considered as 100% for each individual experiment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ns, non-significant.

For statistical analysis, groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test (A–E).

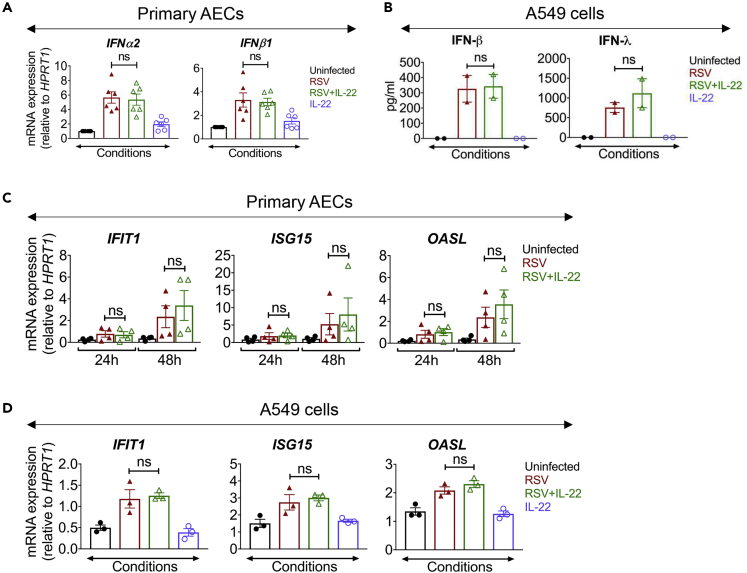

IL-22 Regulates RSV Production without Altering Expression of Type I and Type III Interferons

Type I IFNs play a crucial role in host defense against viruses and upregulate several IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) that play important roles in eliminating the virus from infected cells (Baturcam et al., 2019; Edsbacker et al., 2019; Mahony et al., 2017). In addition, type III IFNs (IFN-λ) have been also implicated in anti-viral host defense (Kotenko, 2011). Activation of both STAT1 and STAT3 has been demonstrated in target cells in response to type I and III IFNs (Chung et al., 1997; Kotenko, 2011; van Boxel-Dezaire et al., 2006; Yang et al., 1996). We, therefore, examined whether the anti-viral effects of IL-22 are mediated by increased expression of ISGs in the AECs. Surprisingly, we observed that IL-22 did not alter the gene expression of type I IFNs (IFN-α2 and IFN-β1) in six different primary AECs after 24 h of RSV infection (Figure 3A). We also observed that the release of both IFN-β and IFN-λ from RSV-infected A549 cells remained unaltered after IL-22 treatment (Figure 3B). We did not detect any IFNs in the culture medium collected from the basolateral surface of primary AECs. In addition, IL-22 did not cause any change in the expression of different ISGs (IFIT1, ISG15, and OASL) in the RSV-infected primary AECs as well as in A549 cells at 24 h after infection (Figures 3C and 3D). Taken together, these data showed that IL-22 inhibits RSV production in epithelial cells that is dependent on STAT3 activation, but it does not result in increased type I or type III IFN production.

Figure 3.

IL-22 Treatment Does Not Alter Expression of Type I and Type III Interferons in RSV-Infected Epithelial Cells

(A) mRNA expression of IFNα2 (left) and IFNβ1 (right) in primary AECs of the human subjects measured by quantitative RT-PCR at 24 h after RSV infection ± IL-22 treatment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 6 independent subjects. ns, non-significant.

(B) Protein expression corresponding to IFN-β (left) and IFN-λ (right) in A549 cells infected with RSV ± IL-22, detected by ELISA at 24 h p.i. Data shown are mean ± SEM from 2 independent experiments. ns, non-significant.

(C and D) mRNA expressions of ISGs (IFIT1, ISG15, and OASL) in (C) primary AECs and (D) A549 cells measured by quantitative RT-PCR at the given time points p.i. Data shown are mean ± SEM of (C) 4 independent subjects and (D) 3 independent experiments. ns, non-significant.

For statistical analysis, groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test (A–D). See Figure S3.

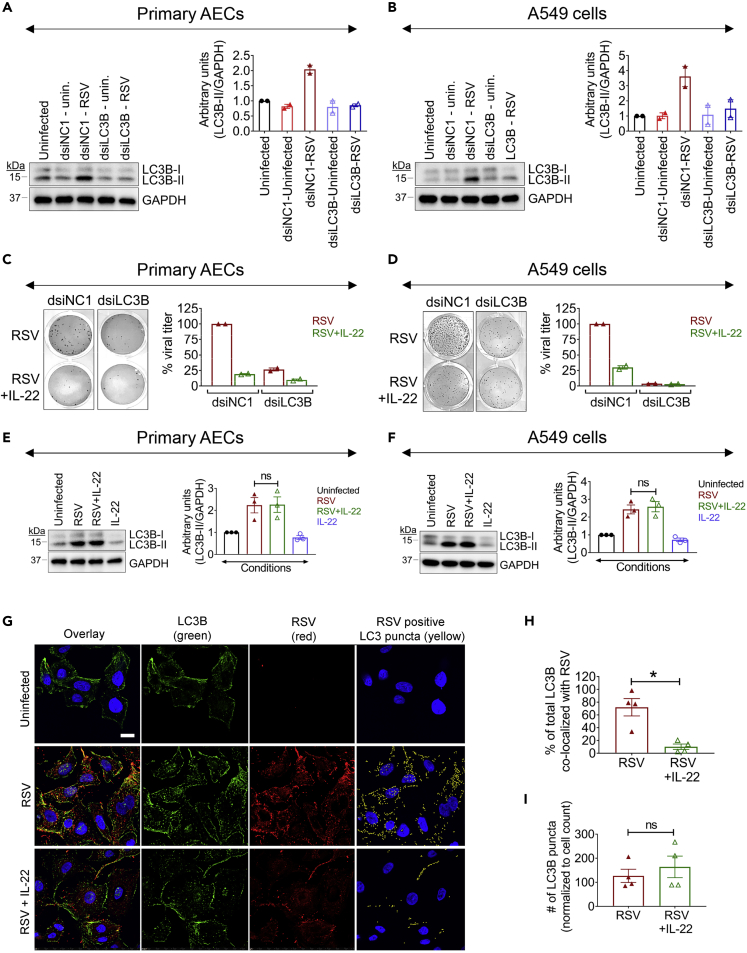

RSV Infection Upregulates LC3B Expression and Then Hijacks the Autophagic Machinery by Co-localizing with LC3B Facilitating Virus Production

We next considered an alternate STAT3-mediated pathway downstream of IL-22 that could play a role in suppressing viral infection, which was cellular autophagy, a strategy that cells use in times of stress to recycle otherwise unusable cellular parts and that has been also shown to promote antiviral immunity. Indeed, viruses are known to subvert or hijack components of the autophagic machinery for their own survival benefit (Beale et al., 2014; Corona et al., 2018; Jackson, 2015; Munz, 2014; Robinson et al., 2018). To determine whether RSV infection could impact cellular autophagy, we studied the expression of a key protein associated with the autophagic machinery in RSV-infected cells. During autophagy, a cytosolic form of the microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3B (LC3B-I) is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine to form a lipidated LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (LC3B-II), which then associates with autophagosomal membranes and is considered a universal marker for the onset of autophagy (Mizushima et al., 2010). Upon RSV infection of both primary AECs and A549 cells, we observed a significant increase in LC3B-II expression (Figures S3A and S3B) showing that RSV infection could indeed have an effect on the cellular autophagic machinery.

To determine whether and how LC3B expression might be functionally influencing RSV infection of the epithelial cells, we knocked down LC3B expression by transfecting both primary AECs and A549 cells with dicer-substrate short interfering RNA (dsiRNA) against LC3B (dsiLC3B) or with a non-target negative control (NC) small interfering RNA (dsiNC1) (see Transparent Methods). We effectively knocked down LC3B, as we observed an impressive increase in cellular LC3B-II levels at 48 h after RSV infection in control dsiNC1-transfected primary AECs or A549 cells, but not in cells transfected with dsiLC3B (Figures 4A and 4B). Importantly, this loss of LC3B also severely hampered RSV production (Figures 4C and 4D), suggesting that RSV requires the autophagic machinery for productive infection. This decreased viral load from the LC3B knocked down cells was also similar to IL-22-treated cells at 48 h after infection (Figures 4C and 4D), further correlating suppression of RSV infection by IL-22 with the autophagic pathway.

Figure 4.

IL-22 Blocks Co-localization of RSV and LC3B

(A and B) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantitation (right) for LC3B expression in dsiLC3B-transfected (A) primary AECs and (B) A549 cells after RSV infection. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments.

(C and D) Representative viral plaques (left) and quantitated viral titer (right) in dsiLC3B-transfected (C) primary AECs and (D) A549 cells after RSV infection and treated with/without IL-22. Percent viral titer for RSV-infected dsiNC1 control considered as 100% for each individual experiment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments.

(E and F) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantitation (right) for LC3B expression in (E) primary AECs and (F) A549 cells after RSV ± IL-22 treatment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ns, non-significant.

(G) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining of RSV (red), LC3B (green), and nuclei (blue) in A549 cells after RSV ± IL-22 treatment along with uninfected cells. The yellow spots (rightmost panel) show the LC3B puncta that are co-positive for RSV. Images were taken at 60× magnification, 1.4 numerical aperture. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(H) Co-localization was assessed by determining the degree of overlap on a per pixel basis. RSV and LC3 emissions were first segmented based on intensity to generate a binary mask. Co-localization was determined using a binary “having” statement to identify LC3-positive puncta containing RSV. It was found that 72.1% of the total LC3 area was co-localized with RSV in the RSV-infected cells, whereas only 10.2% was co-localized with RSV in the RSV + IL-22-treated group.

(I) Number of LC3B puncta normalized to the cell count in RSV and RSV ± IL-22-treated groups.

Representative data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ns, non-significant.

For statistical analysis, groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test (A–F) and Mann-Whitney test (G–I).

We next explored how RSV regulated the autophagic process through LC3B, and whether IL-22 might influence this process. We did not observe a significant difference in LC3B-II expression after IL-22 treatment in infected primary AECs and A549 cells (Figures 4E and 4F). Given that viruses have been shown to subvert LC3B for their propagation in infected cells (Corona et al., 2018; Jackson, 2015; Munz, 2014; Robinson et al., 2018), we next explored the possibility that RSV might associate with LC3B, which was compromised by IL-22. Confocal microscopy revealed that RSV particles indeed co-localized with LC3B in infected A549 cells and IL-22 treatment interfered with this process (Figure 4G); IL-22 was found to reduce RSV-LC3B co-localization by almost 7-fold (Figures 4G and 4H). It was found that 72.1% of the total LC3 area was co-localized with RSV in the RSV-infected cells, whereas only 10.2% was co-localized with RSV in the RSV + IL22-treated group (Figure 4H). Moreover, this imaging approach also showed a marked reduction in RSV signal in the presence of IL-22 in the infected cells, whereas the LC3B signal was largely maintained (Figure 4I), as also observed by immunoblotting (Figures 4E and 4F). Taken together, the data showed that IL-22 treatment does not suppress RSV-mediated increase in LC3B expression. Rather, IL-22 has the ability to disrupt LC3B-virus association.

RSV Inhibits Autophagy by Blocking Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion, whereas IL-22 Promotes Cellular Autophagy in a STAT3-Dependent Manner

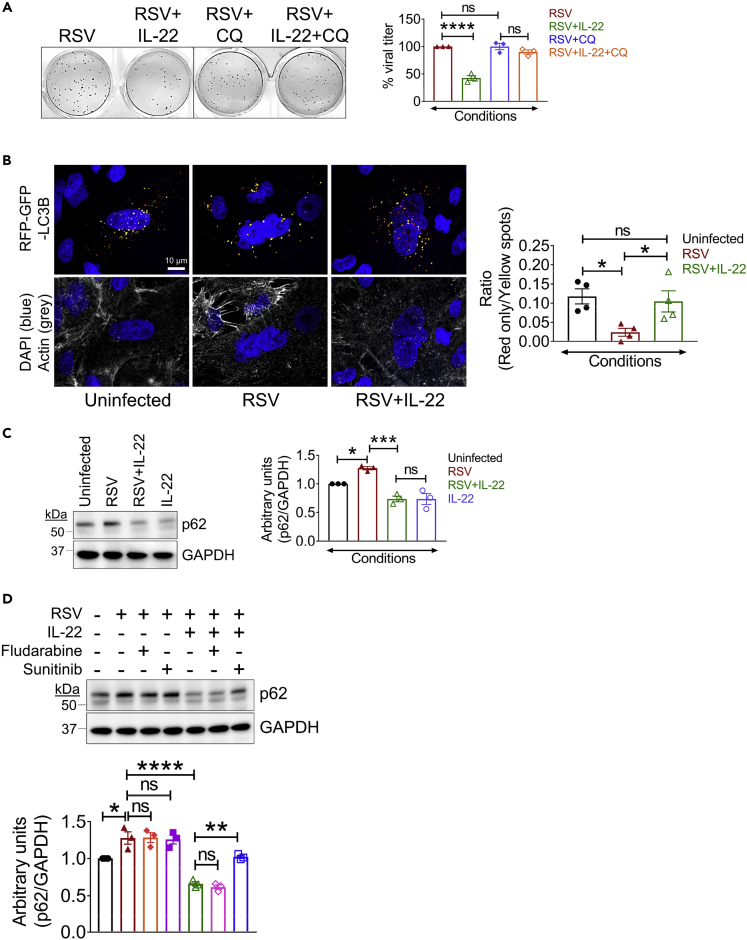

To determine whether active autophagy was required for productive infection, we pre-treated A549 cells with an autophagic inhibitor, chloroquine (CQ), which raises lysosomal pH and inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion (Mauthe et al., 2018), and then infected the cells with RSV. Comparing RSV-infected cells with RSV + CQ cells, we observed that blocking the process of autophagy with CQ did not impair viral production in any way (Figure 5A), suggesting that LC3B-II rather than the process of autophagy was important for virus production. We did, however, observe that CQ ablated IL-22-mediated suppression of RSV production (Figure 5A), showing that the ability of IL-22 to inhibit RSV production relies on maintenance of active cellular autophagy.

Figure 5.

IL-22 Promotes Cellular Autophagy in a STAT3-Dependent Manner

(A) Representative viral plaques (left) and quantitated percent viral titer (right) in RSV-infected A549 cells with/without IL-22 and/or chloroquine treatment. Percent viral titer for RSV alone considered as 100% for each individual experiment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, non-significant.

(B) Representative images (left) of A549 cells transduced with tandem sensor RFP-GFP-LC3B baculoviral particles showing immunofluorescent autophagosomes (yellow puncta) and autolysosomes (red puncta) in the indicated treatment groups. Images taken at 60× magnification. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantitation (right) performed using spot detection to identify puncta. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ns, non-significant.

(C) Representative immunoblot (left) and quantitation (right) of p62 expression in A549 cells after RSV ± IL-22 treatment. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ns, non-significant.

(D) Representative immunoblot (top) and quantitation (bottom) of p62 expression in A549 cells infected with RSV ± IL-22 and treated with or without fludarabine or sunitinib. Data shown are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, non-significant.

For statistical analysis, groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test (A–D).

We further studied the impact of RSV on cellular autophagy and the effect of IL-22 on this process by monitoring the intracellular residence of LC3B. At the early stages of cellular autophagy, LC3B-II is recruited to autophagosomal membranes, triggering the onset of autophagy. Later, LC3B-II resides in autolysosomes formed by the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes, causing degradation of intra-autophagosomal components (Mizushima et al., 2010). To determine whether RSV inhibited this process, we transduced A549 cells with a pH-sensitive tandem RFP-GFP-LC3B plasmid vector that monitors the formation of autolysosomes from autophagosomes. The acidic pH of autolysosomes causes selective degradation of the acid-sensitive GFP, but not RFP, and thus autophagosomes can be identified by yellow puncta (combined GFP + RFP signal), whereas autolysosomes can be identified by red puncta (RFP signal only). We transduced A549 cells with RFP-GFP-LC3B for 24 h, infected them with RSV, and followed with IL-22 treatment. To monitor baseline autophagic activity, a fraction of the transduced cells was not exposed to either RSV or IL-22. Compared with the uninfected condition, we observed that both RSV- and RSV + IL-22-treated cells had increased syncytia (multinucleated cells), a signature morphology for RSV infection, as visualized by nuclear staining (Figure 5B). Quantitation based on spot identification of yellow and red puncta revealed a significant decrease in autolysosome formation in RSV-infected cells compared with that in uninfected cells. Importantly, IL-22 treatment after RSV infection restored the basal level of autolysosomes and hence cellular autophagy in the infected cells (Figure 5B), showing that IL-22 can prevent RSV-mediated block in the formation of autolysosomes, which is essential to maintain cellular autophagy.

Taken together, the data showed that RSV infection initially triggers autophagosome formation but then subsequently blocks autophagosome fusion with lysosomes to prevent the formation of autolysosomes, which can be detrimental for viral survival. IL-22 can release viral control of autophagosomes and restore cellular autophagy. Although the imaging studies showed an increase in autolysosome formation in the presence of IL-22 in RSV-infected cells, it did not prove restoration of functional autophagy. We, therefore, assessed autophagic flux, which is a better index of autophagic activity (Klionsky et al., 2016). The expression level of p62 (also called sequestosome 1 [SQSTM1]), a substrate degraded during active autophagy, is an accepted measure of autophagic flux in a cell (Bjorkoy et al., 2009). p62 levels were examined by immunoblotting in the context of RSV infection in the presence or absence of IL-22. We observed that the level of p62 was significantly lower in RSV-infected A549 cells treated with IL-22 when compared with that in infected cells that were left untreated (Figure 5C). Thus, IL-22 did indeed restore autophagic flux in RSV-infected cells with concomitant reduction in RSV production, as shown in Figures 1A and 1C. Moreover, this IL-22-mediated promotion of autophagic flux (reduction in p62 levels) was blocked by sunitinib treatment (Figure 5D), which was consistent with the requirement for STAT3 activation in inhibition of RSV production, as depicted in Figure 2E.

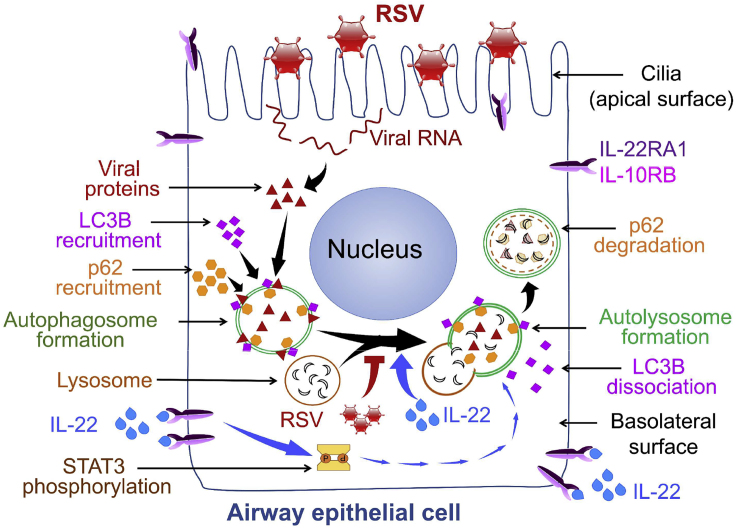

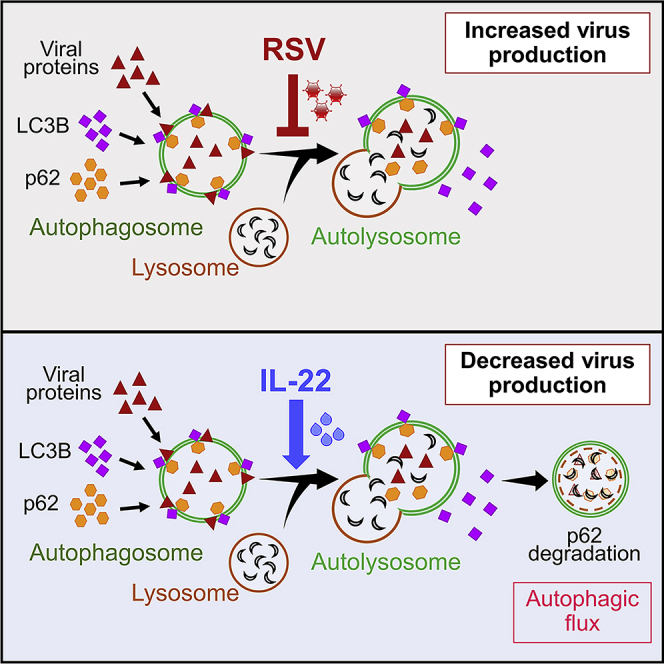

Discussion

The protective role of IL-22 in maintaining epithelial barrier integrity in the lung and the gut and in the induction of epithelial innate immunity in response to different pathogens is well established (Aujla et al., 2008; Aujla and Kolls, 2009; Sonnenberg et al., 2011). By demonstrating the ability of IL-22 to support cellular autophagy, our study provides a new insight into host defense functions of IL-22. We offer the following working model (Figure 6): RSV infection of lung epithelial cells first initiates the formation of autophagosomes in the epithelial cells but then blocks continuation/completion of the autophagic pathway by inhibiting autophagosome fusion with lysosomes through association with LC3B-II thereby preventing the formation of autolysosomes. This block at the autophagosome stage presumably provides a “safe space” in which to allow the virus to replicate and prevents the viral destruction that would normally occur in the acidic environment of the autolysosomes. IL-22 treatment, however, can prevent this blockade with restoration of autophagic flux, the net result being lower virus production.

Figure 6.

Schematic of Working Model

Autophagy is important in multiple biological processes and plays a central role in cell survival during nutrient deprivation and infections (Boya et al., 2013; Deretic and Levine, 2009; Moreau et al., 2010). The process of autophagy involves sequestration of cytosolic cargo, including damaged organelles, in autophagosomes that fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes in which the engulfed constituents undergo degradation and are released back for reuse by the cell. Recent studies show that this process provides antiviral immunity by causing degradation of viral proteins in infected cells (Jackson, 2015; Lennemann and Coyne, 2015). Antiviral effects of IL-22 have been previously appreciated, whereas the ability of IL-22 to reduce virus production from infected cells by promoting cellular autophagy has not been described heretofore. IL-22 was recently shown to be well tolerated in a Phase I clinical trial positioning the agent well for further trials to test efficacy in the control of inflammatory diseases (Tang et al., 2019). Our findings suggest IL-22 as a therapeutic option in limiting RSV-induced illness in vulnerable populations because no effective vaccine against RSV is currently available.

Viruses are known to utilize autophagosomes as a replication niche (Jackson, 2015). Several viruses, especially picornaviruses, have been shown to hijack the cellular autophagic machinery for stabilization of its proteins and/or for viral replication (Beale et al., 2014; Corona et al., 2018; Jackson, 2015; Munz, 2014; Robinson et al., 2018). Recently, another report associated RSV with autophagy in HEp-2 epithelial cells in which RSV replication was promoted by autophagy-mediated inhibition of apoptosis through an ROS-AMPK signaling axis (Li et al., 2018). We speculate that RSV inhibits macroautophagy rather than microautophagy or chaperone-mediated autophagy pathway (Parzych and Klionsky, 2014). One question that remains to be answered in further studies is precisely how RSV subverts LC3B to block autophagosome-lysosome fusion.

Our data suggest that the LC3B protein is co-opted for virus production, and during this process cellular autophagy is reduced in the infected cells as evident from increased levels of p62 in the cells. Also, blocking autophagy by CQ did not affect virus production showing that the process of autophagy per se is not required for virus production. Rather, promotion of autophagy by IL-22 is actually detrimental for virus production. However, it is important to note that we did not find any evidence of increased type I IFN or type III IFN production or increase in expression of ISGs in the infected cells in the presence of IL-22. In RSV-infected macrophages, autophagy-mediated increase in transforming growth factor-β production was shown to promote type I IFN production to limit virus production (Pokharel et al., 2016). In a different study, infection of LC3b–/– mice by RSV caused worse pathology and increased viral transcripts in the lungs (Reed et al., 2015). As the viral titer in the lungs was not reported, it is unknown whether the increased inflammation and pathology were due to increased viral load, as suggested by our study. It is also possible that lack of LC3B did not cause productive infection but that accumulation of viral proteins in the absence of autophagy induced a pro-inflammatory response in the infected lungs. Taken in aggregate, functional autophagy supported by IL-22 confers host-protection.

Our observations bring to the fore another beneficial effect of IL-22 on host cells in addition to maintenance of barrier function and induction of defensins (Aujla et al., 2008; Aujla and Kolls, 2009; Sonnenberg et al., 2011). It is interesting that promotion of autophagy was dependent on STAT3, although IL-22 treatment activated both STAT1 and STAT3 in the AECs. This differs from the anti-viral role of IL-22 against rotavirus infection in the gut that is dependent on STAT1 activation and IFN-λ, a Type III IFN (Hernandez et al., 2015). The mechanism by which IL-22-activated STAT3 promotes autophagy, whether involving nuclear or mitochondrial functions, remains to be determined in future studies. Taken together, these findings emphasize that the mechanisms underlying the protective effects of IL-22 are context and pathogen specific. As published by us previously, RSV infection in early life causes dysfunction of regulatory T cells and increases the risk for asthma in later life (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2012). Limiting virus load with IL-22 may achieve the dual benefit of both stemming severity of illness in early life and reducing the risk for asthma in later life.

Limitations of the Study

Our study demonstrates an anti-viral role of IL-22 that limits viral yield from infected airway and alveolar epithelial cells in culture and also in the lungs of newborn mice. Although we show that the anti-viral effect of IL-22 involves blockade of hijacking of the cellular autophagic machinery by RSV, the underlying mechanism remains to be elucidated. Also, the precise role of STAT3 in mediating the anti-viral effect of IL-22 needs further study.

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Prabir Ray (rayp@pitt.edu).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

All data are included in the published article and the Supplemental Information files and any additional information will be available from the lead contact upon request.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Morgan Jessup for assistance with confocal microscopy, Drs. Stokes Peebles and Martin Moore for sharing the RSV strains, Dr. J.E. Durbin for providing NY3.2 STAT1−/− cells, and Dr. Sreejata Raychaudhuri for performing pilot immunoblotting experiments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AI100012, HL122307, and HL114453 (to P.R.) and HL113956, AI106684, and AI048927 (to A. R.).

Author Contributions

P.R. conceptualized the study. S.D., P.R., and A.R. designed the experiments. S.D., M.G., J.C., S.H., and J.Z. performed the experiments. S.D., C.S.C., M.R., P.R., and A.R. analyzed the data. M.M.M., J.M.P., J.K.K., J.W., and S.E.W. provided samples, reagents, and technical support. S.D., P.R., and A.R. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101256.

Supplemental Information

References

- Abarca K., Jung E., Fernandez P., Zhao L., Harris B., Connor E.M., Losonsky G.A. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity of motavizumab, a humanized, enhanced-potency monoclonal antibody for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection in at-risk children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2009;28:267–272. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818ffd03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aujla S.J., Chan Y.R., Zheng M., Fei M., Askew D.J., Pociask D.A., Reinhart T.A., McAllister F., Edeal J., Gaus K. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat. Med. 2008;14:275–281. doi: 10.1038/nm1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aujla S.J., Kolls J.K. IL-22: a critical mediator in mucosal host defense. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2009;87:451–454. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baturcam E., Vollmer S., Schluter H., Maciewicz R.A., Kurian N., Vaarala O., Ludwig S., Cunoosamy D.M. MEK inhibition drives anti-viral defence in RV but not RSV challenged human airway epithelial cells through AKT/p70S6K/4E-BP1 signalling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019;17:78. doi: 10.1186/s12964-019-0378-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale R., Wise H., Stuart A., Ravenhill B.J., Digard P., Randow F. A LC3-interacting motif in the influenza A virus M2 protein is required to subvert autophagy and maintain virion stability. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkoy G., Lamark T., Pankiv S., Overvatn A., Brech A., Johansen T. Monitoring autophagic degradation of p62/SQSTM1. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:181–197. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P., Reggiori F., Codogno P. Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:713–720. doi: 10.1038/ncb2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand S., Beigel F., Olszak T., Zitzmann K., Eichhorst S.T., Otte J.M., Diepolder H., Marquardt A., Jagla W., Popp A. IL-22 is increased in active Crohn's disease and promotes proinflammatory gene expression and intestinal epithelial cell migration. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G827–G838. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00513.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno S.M., Gonzalez P.A., Riedel C.A., Carreno L.J., Vasquez A.E., Kalergis A.M. Local cytokine response upon respiratory syncytial virus infection. Immunol. Lett. 2011;136:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C.D., Liao J., Liu B., Rao X., Jay P., Berta P., Shuai K. Specific inhibition of Stat3 signal transduction by PIAS3. Science. 1997;278:1803–1805. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5344.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P.L., Graham B.S. Viral and host factors in human respiratory syncytial virus pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2008;82:2040–2055. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01625-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona A.K., Saulsbery H.M., Corona Velazquez A.F., Jackson W.T. Enteroviruses remodel autophagic trafficking through regulation of host SNARE proteins to promote virus replication and cell exit. Cell Rep. 2018;22:3304–3314. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Raundhal M., Chen J., Oriss T.B., Huff R., Williams J.V., Ray A., Ray P. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of newborn CX3CR1-deficient mice induces a pathogenic pulmonary innate immune response. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e94605. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.94605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V., Levine B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:527–549. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudakov J.A., Hanash A.M., van den Brink M.R. Interleukin-22: immunobiology and pathology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015;33:747–785. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edsbacker E., Serviss J.T., Kolosenko I., Palm-Apergi C., De Milito A., Tamm K.P. STAT3 is activated in multicellular spheroids of colon carcinoma cells and mediates expression of IRF9 and interferon stimulated genes. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:536. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37294-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsey A.R., Hennessey P.A., Formica M.A., Cox C., Walsh E.E. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1749–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D., Kong X., Weng H., Park O., Wang H., Dooley S., Gershwin M.E., Gao B. Interleukin-22 promotes proliferation of liver stem/progenitor cells in mice and patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:188–198.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonceca A.M., Flanagan B.F., Trinick R., Smyth R.L., McNamara P.S. Primary airway epithelial cultures from children are highly permissive to respiratory syncytial virus infection. Thorax. 2012;67:42–48. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan S., Erviti A., Caballero M.T., Vallone F., Zanone S.M., Losada J.V., Bianchi A., Acosta P.L., Talarico L.B., Ferretti A. Mortality due to respiratory syncytial virus. Burden and risk factors. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017;195:96–103. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0658OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno Brias S., Stack G., Stacey M.A., Redwood A.J., Humphreys I.R. The role of IL-22 in viral infections: paradigms and paradoxes. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:211. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guabiraba R., Besnard A.G., Marques R.E., Maillet I., Fagundes C.T., Conceicao T.M., Rust N.M., Charreau S., Paris I., Lecron J.C. IL-22 modulates IL-17A production and controls inflammation and tissue damage in experimental dengue infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013;43:1529–1544. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Wu W., Cen Z., Li X., Kong Q., Zhou Q. IL-22-producing Th22 cells play a protective role in CVB3-induced chronic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy by inhibiting myocardial fibrosis. Virol. J. 2014;11:230. doi: 10.1186/s12985-014-0230-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.B. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1917–1928. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez P.P., Mahlakoiv T., Yang I., Schwierzeck V., Nguyen N., Guendel F., Gronke K., Ryffel B., Hoelscher C., Dumoutier L. Interferon-lambda and interleukin 22 act synergistically for the induction of interferon-stimulated genes and control of rotavirus infection. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:698–707. doi: 10.1038/ni.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman M.J., Patel D.A., Zhang Y., Patel A.C. Host epithelial-viral interactions as cause and cure for asthma. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov S., Renneson J., Fontaine J., Barthelemy A., Paget C., Fernandez E.M., Blanc F., De Trez C., Van Maele L., Dumoutier L. Interleukin-22 reduces lung inflammation during influenza A virus infection and protects against secondary bacterial infection. J. Virol. 2013;87:6911–6924. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02943-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson W.T. Viruses and the autophagy pathway. Virology. 2015;479-480:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.E., Gonzales R.A., Olson S.J., Wright P.F., Graham B.S. The histopathology of fatal untreated human respiratory syncytial virus infection. Mod. Pathol. 2007;20:108–119. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C., Logsdon N.J., Walter M.R. Structure of IL-22 bound to its high-affinity IL-22R1 chain. Structure. 2008;16:1333–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.J., Nazli A., Rojas O.L., Chege D., Alidina Z., Huibner S., Mujib S., Benko E., Kovacs C., Shin L.Y. A role for mucosal IL-22 production and Th22 cells in HIV-associated mucosal immunopathogenesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:670–680. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D.J., Abdelmohsen K., Abe A., Abedin M.J., Abeliovich H., Acevedo Arozena A., Adachi H., Adams C.M., Adams P.D., Adeli K. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition) Autophagy. 2016;12:1–222. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotenko S.V. IFN-lambdas. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotenko S.V., Izotova L.S., Mirochnitchenko O.V., Esterova E., Dickensheets H., Donnelly R.P., Pestka S. Identification of the functional interleukin-22 (IL-22) receptor complex: the IL-10R2 chain (IL-10Rbeta ) is a common chain of both the IL-10 and IL-22 (IL-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor, IL-TIF) receptor complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2725–2732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy N., Khare A., Oriss T.B., Raundhal M., Morse C., Yarlagadda M., Wenzel S.E., Moore M.L., Peebles R.S., Jr., Ray A. Early infection with respiratory syncytial virus impairs regulatory T cell function and increases susceptibility to allergic asthma. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1525–1530. doi: 10.1038/nm.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Thakar M.S., Ouyang W., Malarkannan S. IL-22 from conventional NK cells is epithelial regenerative and inflammation protective during influenza infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:69–82. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune D., Dumoutier L., Constantinescu S., Kruijer W., Schuringa J.J., Renauld J.C. Interleukin-22 (IL-22) activates the JAK/STAT, ERK, JNK, and p38 MAP kinase pathways in a rat hepatoma cell line. Pathways that are shared with and distinct from IL-10. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33676–33682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennemann N.J., Coyne C.B. Catch me if you can: the link between autophagy and viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004685. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Li J., Zeng R., Yang J., Liu J., Zhang Z., Song X., Yao Z., Ma C., Li W. Respiratory syncytial virus replication is promoted by autophagy-mediated inhibition of apoptosis. J. Virol. 2018;92:e02193-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02193-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesman R.M., Buchholz U.J., Luongo C.L., Yang L., Proia A.D., DeVincenzo J.P., Collins P.L., Pickles R.J. RSV-encoded NS2 promotes epithelial cell shedding and distal airway obstruction. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:2219–2233. doi: 10.1172/JCI72948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs N.W., Moore M.L., Rudd B.D., Berlin A.A., Collins R.D., Olson S.J., Ho S.B., Peebles R.S., Jr. Differential immune responses and pulmonary pathophysiology are induced by two different strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:977–986. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony R., Gargan S., Roberts K.L., Bourke N., Keating S.E., Bowie A.G., O'Farrelly C., Stevenson N.J. A novel anti-viral role for STAT3 in IFN-alpha signalling responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017;74:1755–1764. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2435-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauthe M., Orhon I., Rocchi C., Zhou X., Luhr M., Hijlkema K.J., Coppes R.P., Engedal N., Mari M., Reggiori F. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 2018;14:1435–1455. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1474314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur N.I., Martinon-Torres F., Baraldi E., Fauroux B., Greenough A., Heikkinen T., Manzoni P., Mejias A., Nair H., Papadopoulos N.G. Lower respiratory tract infection caused by respiratory syncytial virus: current management and new therapeutics. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015;3:888–900. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P.S., Flanagan B.F., Baldwin L.M., Newland P., Hart C.A., Smyth R.L. Interleukin 9 production in the lungs of infants with severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Lancet. 2004;363:1031–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15838-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner H.C. More on viral bronchiolitis in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1607283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E.C., Barber J., Tripp R.A. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) attachment and nonstructural proteins modify the type I interferon response associated with suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins and IFN-stimulated gene-15 (ISG15) Virol. J. 2008;5:116. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau K., Luo S., Rubinsztein D.C. Cytoprotective roles for autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz C. Influenza A virus lures autophagic protein LC3 to budding sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:130–131. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair H., Nokes D.J., Gessner B.D., Dherani M., Madhi S.A., Singleton R.J., O'Brien K.L., Roca A., Wright P.F., Bruce N. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw P.J.M., Chiu C., Culley F.J., Johansson C. Protective and harmful immunity to RSV infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017;35:501–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parzych K.R., Klionsky D.J. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:460–473. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini M., Calzascia T., Toe J.G., Preston S.P., Lin A.E., Elford A.R., Shahinian A., Lang P.A., Lang K.S., Morre M. IL-7 engages multiple mechanisms to overcome chronic viral infection and limit organ pathology. Cell. 2011;144:601–613. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles R.J., DeVincenzo J.P. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its propensity for causing bronchiolitis. J. Pathol. 2015;235:266–276. doi: 10.1002/path.4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pociask D.A., Scheller E.V., Mandalapu S., McHugh K.J., Enelow R.I., Fattman C.L., Kolls J.K., Alcorn J.F. IL-22 is essential for lung epithelial repair following influenza infection. Am. J. Pathol. 2013;182:1286–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel S.M., Shil N.K., Bose S. Autophagy, TGF-beta, and SMAD-2/3 signaling regulates interferon-beta response in respiratory syncytial virus infected macrophages. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2016;6:174. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PrabhuDas M., Adkins B., Gans H., King C., Levy O., Ramilo O., Siegrist C.A. Challenges in infant immunity: implications for responses to infection and vaccines. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:189–194. doi: 10.1038/ni0311-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed M., Morris S.H., Owczarczyk A.B., Lukacs N.W. Deficiency of autophagy protein Map1-LC3b mediates IL-17-dependent lung pathology during respiratory viral infection via ER stress-associated IL-1. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:1118–1130. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaee F., Linfield D.T., Harford T.J., Piedimonte G. Ongoing developments in RSV prophylaxis: a clinician's analysis. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017;24:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M., Schor S., Barouch-Bentov R., Einav S. Viral journeys on the intracellular highways. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018;75:3693–3714. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2882-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze J., Mackenzie K.J. Republished: novel insights into immune and inflammatory responses to respiratory viruses. Postgrad. Med. J. 2013;89:516–518. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-202291rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart K.A., Paes B.A., Lanctot K.L. Changing costs and the impact on RSV prophylaxis. J. Med. Econ. 2010;13:705–708. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.535577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg G.F., Fouser L.A., Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:383–390. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg G.F., Nair M.G., Kirn T.J., Zaph C., Fouser L.A., Artis D. Pathological versus protective functions of IL-22 in airway inflammation are regulated by IL-17A. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1293–1305. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey M.A., Marsden M., Pham N.T., Clare S., Dolton G., Stack G., Jones E., Klenerman P., Gallimore A.M., Taylor P.R. Neutrophils recruited by IL-22 in peripheral tissues function as TRAIL-dependent antiviral effectors against MCMV. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes K.L., Currier M.G., Sakamoto K., Lee S., Collins P.L., Plemper R.K., Moore M.L. The respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein and neutrophils mediate the airway mucin response to pathogenic respiratory syncytial virus infection. J. Virol. 2013;87:10070–10082. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01347-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K., Ogawa A., Mizoguchi E., Shimomura Y., Andoh A., Bhan A.K., Blumberg R.S., Xavier R.J., Mizoguchi A. IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:534–544. doi: 10.1172/JCI33194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K.Y., Lickliter J., Huang Z.H., Xian Z.S., Chen H.Y., Huang C., Xiao C., Wang Y.P., Tan Y., Xu L.F. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and biomarkers of F-652, a recombinant human interleukin-22 dimer, in healthy subjects. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2019;16:473–482. doi: 10.1038/s41423-018-0029-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boxel-Dezaire A.H., Rani M.R., Stark G.R. Complex modulation of cell type-specific signaling in response to type I interferons. Immunity. 2006;25:361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waidmann O., Kronenberger B., Scheiermann P., Koberle V., Muhl H., Piiper A. Interleukin-22 serum levels are a negative prognostic indicator in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;59:1207. doi: 10.1002/hep.26528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Bai F., Zenewicz L.A., Dai J., Gate D., Cheng G., Yang L., Qian F., Yuan X., Montgomery R.R. IL-22 signaling contributes to West Nile encephalitis pathogenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk K., Witte E., Witte K., Warszawska K., Sabat R. Biology of interleukin-22. Semin. Immunopathol. 2010;32:17–31. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.Q., Liu Y., Zhang B., Liu H., Shao D.D., Liu J.B., Wang X., Zhou L.N., Hu W.H., Ho W.Z. IL-22 suppresses HSV-2 replication in human cervical epithelial cells. Cytokine. 2019;123:154776. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.H., Shi W., Basu L., Murti A., Constantinescu S.N., Blatt L., Croze E., Mullersman J.E., Pfeffer L.M. Direct association of STAT3 with the IFNAR-1 chain of the human type I interferon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8057–8061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Chassaing B., Shi Z., Uchiyama R., Zhang Z., Denning T.L., Crawford S.E., Pruijssers A.J., Iskarpatyoti J.A., Estes M.K. Viral infection. Prevention and cure of rotavirus infection via TLR5/NLRC4-mediated production of IL-22 and IL-18. Science. 2014;346:861–865. doi: 10.1126/science.1256999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cobleigh M.A., Lian J.Q., Huang C.X., Booth C.J., Bai X.F., Robek M.D. A proinflammatory role for interleukin-22 in the immune response to hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1897–1906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Valdez P.A., Danilenko D.M., Hu Y., Sa S.M., Gong Q., Abbas A.R., Modrusan Z., Ghilardi N., de Sauvage F.J. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat. Med. 2008;14:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the published article and the Supplemental Information files and any additional information will be available from the lead contact upon request.