Abstract

Objective

Physical activity may provide a means for the prevention of cardiovascular disease via improving microvascular function. Therefore, this study investigated whether physical activity is associated with skin and retinal microvascular function.

Methods

In The Maastricht Study, a population‐based cohort study enriched with type 2 diabetes (n = 1298, 47.3% women, aged 60.2 ± 8.1 years, 29.5% type 2 diabetes), we studied whether accelerometer‐assessed physical activity and sedentary time associate with skin and retinal microvascular function. Associations were studied by linear regression and adjusted for major cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, we investigated whether associations were stronger in type 2 diabetes.

Results

In individuals with type 2 diabetes, total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity were independently associated with greater heat‐induced skin hyperemia (regression coefficients per hour), respectively, 10 (95% CI: 1; 18) and 36 perfusion units (14; 58). In individuals without type 2 diabetes, total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity were not associated with heat‐induced skin hyperemia. No associations with retinal arteriolar %‐dilation were identified.

Conclusion

Higher levels of total and higher‐intensity physical activity were associated with greater skin microvascular vasodilation in individuals with, but not in those without, type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: cohort studies, diabetes mellitus, type 2, exercise, microcirculation, sedentary behavior

Abbreviations

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- MU

measurement units

- NGM

normal glucose metabolism

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- PU

perfusion units

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

1. INTRODUCTION

Microvascular dysfunction is an important underlying mechanism in common diseases, such as heart failure,1 (lacunar) stroke,2 depression,3 cognitive decline,4 chronic kidney disease,5 and neuropathy,6 which occur in the general population and more frequently in individuals with T2D.7 It is therefore important to identify, in particular modifiable, factors that contribute to the development of microvascular dysfunction, as these can be targeted in preventive strategies.

Physical inactivity may be one such modifiable risk factor, as may sedentary behavior, which refers to activities that do not increase energy expenditure substantially above the resting level, such as sitting, watching television, and using the computer.8

Indeed, low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary time have been shown to be associated with macrovascular diseases9 (eg, stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral arterial disease) and may act through inducing large artery endothelial dysfunction.10, 11 Low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary time have also been shown to be associated with diseases that may be partly or wholly of microvascular origin.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Thus, we hypothesized that low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary time may affect microvascular (endothelial) function. In support, several small (mostly intervention) studies have shown beneficial effects of physical activity,19, 20, 21, 22 and adverse effects of sedentary behavior,19, 23, 24, 25, 26 on microvascular function. However, it is unclear whether daily life habitual physical activity, as compared to exercise programs,20, 22 also beneficially affects microvascular function. Earlier studies were conducted in small numbers of individuals,19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 which limits translation to the general population, or were based on self‐reported measures of physical activity and sedentary behavior27 which are known to be less precise and valid than objective measures.28

Mechanistically, higher levels of physical activity and lower levels of sedentary time are thought to increase nitric oxide bioavailability,29, 30 presumably in conjunction with beneficial effects on low‐grade inflammation,31, 32 both of which may improve microvascular (endothelial) function.33 As hyperglycemia has detrimental effects on nitric oxide bioavailability34 and microvascular (endothelial) function,35 the associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with microvascular (endothelial) function may differ between (ie, may be stronger in) individuals with as compared to those without T2D.

In view of these considerations, we investigated, in a population‐based study with oversampling of individuals with T2D, whether objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior were associated with skin microvascular and retinal arteriolar (endothelial) function. In addition, we examined whether these associations differed between individuals with and without T2D. We chose skin and retina for 2 reasons. First, these sites are easily accessible, enabling direct and reproducible36, 37 assessment of microvascular (endothelial) function, as measured by heat‐induced skin hyperemia and flicker light‐induced retinal arteriolar dilation. Second, skin and retina may differ in their associations with physical activity and sedentary behavior, with skin potentially showing stronger associations. This is because skin is important in disseminating exercise‐produced heat,38 whereas retinal blood flow, in contrast, has been shown to be relatively stable during exercise,39, 40 presumably to maintain visual performance.41

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study population and design

We used data from The Maastricht Study, an observational prospective population‐based cohort study. The rationale and methodology have been described previously.42 In brief, the study focuses on the etiology, pathophysiology, complications, and comorbidities of T2D and is characterized by an extensive phenotyping approach. Eligible for participation were all individuals aged between 40 and 75 years and living in the southern part of the Netherlands. Participants were recruited through mass media campaigns and from the municipal registries and the regional Diabetes Patient Registry via mailings. Recruitment was stratified according to known T2D status, with an oversampling of individuals with T2D, for reasons of efficiency. The present report includes cross‐sectional data from the first 3451 participants, who completed the baseline survey between November 2010 and September 2013. The examinations of each participant were performed within a time window of three months. The study has been approved by the institutional medical ethical committee (NL31329.068.10) and the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sports of the Netherlands (Permit 131088‐105234‐PG). All participants gave written informed consent.

2.2. Assessment of glucose metabolism status

To assess glucose metabolism status, all participants (except those who used insulin) underwent a standardized 2‐h 75 gram OGTT after an overnight fast. For safety reasons, participants with a fasting glucose level above 11.0 mmol/L, as determined by a finger prick, did not undergo the OGTT. For these individuals, fasting glucose level and information about diabetes medication use were used to assess glucose metabolism status. Glucose metabolism status was defined according to the World Health Organization 2006 criteria as NGM, impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance (combined as prediabetes), and T2D. Individuals without type 1 diabetes on glucose‐lowering medication were classified as having T2D.42

2.3. Assessment of microvascular function

All participants were asked to refrain from smoking and drinking caffeine‐containing beverages three hours before the measurement. A light meal (breakfast and (or) lunch), low in fat content, was allowed if taken at least 90 minutes prior to the start of the measurements.

Skin blood flow measurements were performed in a climate‐controlled room at 24°C with participants in a supine position. Skin blood flow was measured as described previously by means of a laser Doppler system (Periflux 5000, Perimed,), equipped with a thermostatic laser Doppler probe (PF457) at the dorsal side of the wrist of the left hand. The laser Doppler output was recorded for 25 minutes with a sample rate of 32Hz, which gives semi‐quantitative assessment of skin blood flow expressed in arbitrary PU. Skin blood flow was first recorded unheated for 2 minutes to serve as a baseline. After the 2 minutes of baseline, the temperature of the probe was rapidly and locally increased to 44°C and was then kept constant until the end of the registration. In contrast to earlier work,43 heat‐induced skin hyperemia was expressed not as a percentage of baseline but as perfusion during the 23‐minute heating phase (in PU), because spurious associations between determinants and heat‐induced skin hyperemia expressed as percentage may occur when determinants are associated with baseline skin blood flow (as was the case here; see Supporting Information: Results and Table S3). To investigate associations of heat‐induced skin hyperemia independently of associations with baseline skin blood flow, we adjusted for baseline flow in the regression models (this will not lead to autocorrelation because there was only a weak association between baseline skin blood flow and heat‐induced skin hyperemia).44, 45

For retinal measurements, pupils were dilated with 0.5% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine at least 15 minutes prior to the start of the examination. Retinal arteriolar vasodilation to flicker light exposure was measured by the Dynamic Vessel Analyzer (Imedos). Briefly, a baseline recording of 50 seconds was followed by 40‐second flicker light exposure followed by a 60‐second recovery period. Baseline diameter was calculated as the average diameter size of the 20‐50 seconds recording and was expressed in MU. As determinants were not associated with retinal arteriolar baseline diameter (see Supporting Information: Results and Table S4), flicker light‐induced retinal arteriolar dilation was expressed as a percentage over baseline, based on the average dilation achieved at time points 10 and 40 seconds during the flicker stimulation period. The measurement has extensively been described previously,43 and more details are provided in the Supporting Information.

2.4. Assessment of physical activity and sedentary behavior

Daily activity levels and patterns were measured using the activPAL3TM physical activity monitor (PAL technologies) as has been described previously46 and in the Supporting Information: Methods. Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer for 8 consecutive days, without removing the device at any time. The total amount of physical activity (stepping time) was based on the stepping posture and calculated as the mean time spent stepping during waking time per day, and standing time was not included. The method used to determine waking time has been described elsewhere.46 Higher‐intensity physical activity was defined as hours with a step frequency ≥ 110 steps/min during waking time47, 48; again, standing time was not included. The total amount of sedentary time was based on the sedentary posture (sitting or lying) and calculated as the mean time spent in a sedentary position during waking time per day.46

2.5. Measurement of covariates

A history of CVD, smoking status (never, former, current), alcohol consumption, level of education, occupational status, daily energy intake, mobility limitation, and duration of diabetes were assessed by questionnaire.42 Mobility limitation was obtained from the EuroQol‐5D questionnaire and was defined as having difficulty walking 500 meter or climbing the stairs in the previous week. Energy intake was obtained from a food frequency questionnaire and calculated as the mean energy intake (kcal) per day. Use of antihypertensive, lipid‐modifying, and glucose‐lowering medication was assessed during a medication interview where generic name, dose, and frequency were registered.49 We measured height, weight, waist circumference, office and ambulatory 24‐h blood pressure, plasma glucose levels, serum creatinine, 24‐h urinary albumin excretion (twice), glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and plasma lipid profile as described elsewhere.42 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; in mL/min/1.73m2) was calculated with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CDK‐epi) equation based on both serum creatinine and serum cystatin C.50 The presence of retinopathy was based on fundus photographs taken with an auto fundus camera (Model AFC‐230, Nidek, Gamagori, Japan).

2.6. Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 23.0 (IBM SPSS, IBM Corp). Multivariable linear regression analyses were used to investigate the associations of total physical activity (hour/d), higher‐intensity physical activity (hour/d), and total sedentary time (hour/d) with baseline skin blood flow, baseline retinal arteriolar diameter, heat‐induced skin hyperemia, and flicker light‐induced retinal arteriolar %‐dilation. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, glucose metabolism status, baseline skin blood flow (only for analyses of heat‐induced skin hyperemia), and waking time (to exclude the possibility that estimated effects were influenced by differences in waking hours). Model 2 was additionally adjusted for potential confounders such as body mass index, educational level, mobility limitation, office systolic blood pressure, total‐to‐high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio, triglycerides, smoking status, alcohol consumption, the use of antihypertensive‐ and/or lipid‐modifying medication, and a history of CVD. In model 3a higher‐intensity physical activity was additionally adjusted for total sedentary time. In model 3b, total sedentary time was additionally adjusted for higher‐intensity physical activity. Data were expressed as regression coefficients and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

The Maastricht Study by design oversampled individuals with T2D, and we therefore were able to investigate potential interactions between total physical activity, higher‐intensity physical activity, and total sedentary time with T2D by adding interaction terms to the regression models. In stratified analyses in individuals without T2D, model 1 was additionally adjusted for prediabetes status. To assess whether associations differed by sex or age, interactions between total physical activity, higher‐intensity physical activity, and total sedentary time with sex and age were investigated. In these analyses, interaction terms were the product of total physical activity, higher‐intensity physical activity, or total sedentary time and T2D, sex, or age, respectively.

Collinearity diagnostics (ie, tolerance < 0.10 and/or variance inflation factor > 10) were used to detect multicollinearity between covariates. A P‐value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant except for interaction analyses, where a P interaction < 0.10 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of study population

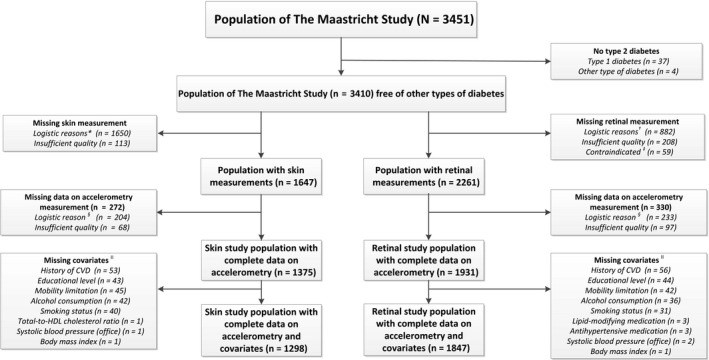

From the initial 3451 participants included, those with other types of diabetes than T2D were excluded (n = 41). Of the remaining 3410 participants, heat‐induced skin hyperemia data were available in 1647. The reasons for missing data were logistical (n = 1650, specified as no laser Doppler equipment available [n = 353], no trained researcher available [n = 264], or technical failure [n = 1033]) or insufficient measurement quality (n = 113). Accelerometry variables were missing in 272 participants, and data on potential confounders were missing in 77 participants. The heat‐induced skin hyperemia study population thus consisted of 1298 participants. Retinal arteriolar reactivity data were available in 2261 participants. The reasons for missing data were logistical (n = 882, specified as no Dynamic Vessel Analyzer equipment available [n = 535], no trained researcher available [n = 227], or no eye drops given for traffic safety reasons [n = 120]), insufficient measurement quality (n = 208), or contraindications (n = 59). Accelerometry variables were missing in 330 participants, particularly due to device availability (n = 233), and data on potential confounders were missing in 84 participants. The retinal arteriolar reactivity study population thus consisted of 1847 participants (Figure 1 shows the flow chart).

Figure 1.

Skin and retinal study population selection. Symbols *=Logistical reasons: no laser Doppler equipment available (n = 353), no trained researcher available (n = 264), and technical failure (n = 1033). †=Logistical reasons: no Dynamic Vessel Analyzer equipment available (n = 535), no trained researcher available (n = 227), and no eye drops given for traffic safety reasons (n = 120). ‡=Contraindicated: history of epilepsy (n = 14), allergy to eye drops (n = 31), and glaucoma or lens implants (n = 14). §=No accelerometer available. ||=Missing values on covariates were not mutually exclusive

General characteristics of skin reactivity study population are shown in Table 1, according to tertiles of total physical activity. This study population had a mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of 60.2 ± 8.1 years, of whom 46.3% were women and 29.5% had T2D (oversampled by design). In addition, when compared to individuals in the lowest tertile of total physical activity, those in the middle and highest tertiles were on average younger, had lower glucose levels, and were less likely to have had a history of CVD (Table 1). The skin study population overlapped for 73% with the retinal study population. Both populations were comparable with regard to age, sex, and cardio‐metabolic risk profile (Table 1). Individuals excluded from the analyses due to missing data on skin or retinal reactivity measurements, accelerometry measurements, or covariates were also highly comparable to individuals included in the study populations with regard to age, sex, and cardio‐metabolic risk profile (Tables S1 and S2).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the skin and retina study populations according to sex‐specific tertiles of total physical activity

| Characteristic | Skin study population | Retinal study population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile 1 of total physical activity (highest) n = 432 | Tertile 2 of total physical activity n = 434 | Tertile 3 of total physical activity (lowest) n = 432 | Tertile 1 of total physical activity (highest) n = 616 | Tertile 2 of total physical activity n = 616 | Tertile 3 of total physical activity (lowest) n = 615 | |

| Range of total physical activity (h/day) in men | 2.21‐4.69 | 1.52‐2.21 | 0.22‐1.52 | 2.25‐4.67 | 1.56‐2.25 | 0.19‐1.56 |

| Range of total physical activity (h/day) in women | 2.27‐5.38 | 1.73‐2.27 | 0.30‐1.73 | 2.33‐5.38 | 1.77‐2.32 | 0.30‐1.77 |

| Age (years) | 59.0 ± 7.5 | 60.4 ± 8.0 | 61.1 ± 8.5 | 58.8 ± 7.7 | 59.5 ± 8.2 | 60.5 ± 8.4 |

| Women | 200 (46.3) | 201 (46.3) | 200 (46.3) | 298 (48.4) | 298 (48.4) | 298 (48.5) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Low | 131 (30.3) | 128 (29.5) | 173 (40.0) | 185 (30.0) | 177 (28.7) | 230 (37.4) |

| Medium | 113 (26.2) | 130 (30.0) | 116 (26.9) | 163 (26.5) | 190 (30.8) | 182 (29.6) |

| High | 188 (43.5) | 176 (40.6) | 143 (33.1) | 268 (43.5) | 249 (40.4) | 203 (33.0) |

| Occupational status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 207 (55.1) | 213 (56.6) | 241 (65.1) | 271 (50.5) | 285 (53.4) | 332 (61.7) |

| Employed | 169 (44.9) | 163 (43.4) | 129 (34.9) | 266 (49.5) | 249 (46.6) | 206 (38.3) |

| Glucose metabolism status | ||||||

| NGM | 277 (64.1) | 244 (56.2) | 178 (41.2) | 413 (67.0) | 369 (59.9) | 274 (44.6) |

| Prediabetes | 73 (16.9) | 83 (19.1) | 60 (13.9) | 93 (15.1) | 106 (17.2) | 87 (14.1) |

| T2D | 82 (19.0) | 107 (24.7) | 194 (44.9) | 110 (17.9) | 141 (22.9) | 254 (41.3) |

| Type 2 diabetes duration (years) | 4.0 [2.5‐7.0] | 5.0 [2.0‐11.0] | 8.0 [3.0‐12.5] | 5.0 [3.0‐9.5] | 5.0 [2.0‐10.0] | 7.0 [3.0‐13.0] |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 3.7 | 26.6 ± 3.8 | 28.4 ± 5.1 | 25.7 ± 3.8 | 26.5 ± 3.9 | 28.3 ± 5.2 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | ||||||

| Men | 97.0 ± 10.0 | 100.4 ± 10.0 | 106.5 ± 13.3 | 96.4 ± 10.0 | 100.3 ± 9.9 | 106.7 ± 13.6 |

| Women | 87.1 ± 10.2 | 88.7 ± 11.5 | 94.1 ± 14.8 | 85.9 ± 10.9 | 88.2 ± 11.2 | 92.8 ± 14.1 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 59 (13.7) | 72 (16.6) | 96 (22.2) | 69 (11.2) | 94 (15.3) | 123 (20.0) |

| Limited mobility | 37 (8.6) | 56 (12.9) | 114 (26.4) | 52 (8.4) | 68 (11.0) | 164 (26.7) |

| Office SBP (mmHg) | 134.1 ± 18.4 | 136.5 ± 17.3 | 137.4 ± 18.9 | 133.8 ± 17.9 | 135.2 ± 18.1 | 135.9 ± 18.1 |

| Office DBP (mmHg) | 76.1 ± 9.3 | 77.3 ± 9.9 | 76.4 ± 9.6 | 75.9 ± 9.9 | 76.9 ± 10.0 | 76.4 ± 9.9 |

| Ambulatory 24‐h SBP (mmHg) | 120.9 ± 11.2 | 120.1 ± 12.1 | 120.0 ± 11.8 | 118.7 ± 11.0 | 118.7 ± 11.5 | 117.7 ± 11.7 |

| Ambulatory 24‐h DBP (mmHg) | 74.7 ± 7.2 | 73.7 ± 7.3 | 74.1 ± 7.5 | 73.3 ± 7.1 | 73.3 ± 7.2 | 72.8 ± 7.2 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never/former/current | 169/227/36 | 140/259/35 | 120/228/84 | 265/304/47 | 211/345/60 | 173/326/116 |

| % (never/former/current) | 39.1/52.5/8.3 | 32.3/59.7/8.1 | 27.8/52.8/19.4 | 43.0/49.4/7.6 | 34.3/56.0/9.7 | 28.1/53.0/18.9 |

| Alcohol consumption (high) | 142 (32.9) | 113 (26.0) | 95 (22.0) | 182 (29.5) | 145 (23.5) | 135 (22.0) |

| Energy intake (kcal/day) | 2221.3 ± 586.1 | 2193.8 ± 560.8 | 2101.3 ± 586.6 | 2245.9 ± 619.1 | 2155.3 ± 566.6 | 2083.0 ± 571.4 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.8 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 2.0 |

| 2‐h postload glucose (mmol/L) | 7.3 ± 4.0 | 7.9 ± 4.2 | 9.2 ± 4.7 | 7.1 ± 3.7 | 7.6 ± 4.0 | 8.9 ± 4.6 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 6.1 ± 1.1 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 39.5 ± 6.9 | 40.7 ± 8.3 | 44.1 ± 12.2 | 38.7 ± 8.0 | 39.5 ± 8.1 | 43.1 ± 11.5 |

| Total‐to‐HDL cholesterol ratio | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 1.2 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 5.1 ± 1.2 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.1 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.9 |

| Antihypertensive medication use | 137 (31.7) | 176 (40.6) | 239 (55.3) | 175 (28.4) | 233 (37.8) | 307 (49.9) |

| Lipid‐modifying medication use | 132 (30.6) | 161 (37.1) | 219 (50.7) | 172 (27.9) | 205 (33.3) | 275 (44.7) |

| Diabetes medication use | ||||||

| Any type | 54 (12.5) | 87 (20.0) | 163 (37.7) | 79 (12.8) | 102 (16.6) | 210 (34.1) |

| Insulin | 6 (1.4) | 19 (4.4) | 59 (13.7) | 18 (2.9) | 20 (3.2) | 69 (11.1) |

| Oral glucose‐lowering medication | 52 (12.0) | 84 (19.4) | 149 (34.5) | 72 (11.7) | 97 (15.7) | 196 (31.9) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 91.2 ± 13.4 | 88.1 ± 14.1 | 85.2 ± 15.8 | 91.1 ± 13.0 | 89.0 ± 14.4 | 85.0 ± 15.4 |

| eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 | 7 (1.6) | 15 (3.5) | 28 (6.6) | 7 (1.1) | 26 (4.2) | 44 (7.2) |

| (Micro)albuminuriaa | 26 (6.1) | 26 (6.0) | 59 (13.8) | 42 (6.9) | 34 (5.6) | 77 (12.4) |

| Retinopathy | 3 (0.8) | 4 (1.0) | 10 (2.6) | 5 (0.8) | 6 (1.0) | 14 (2.3) |

| Baseline skin blood flow before heating (PU)c | 11.9 ± 7.2 | 10.5 ± 5.7 | 10.8 ± 6.3 | 12.0 ± 7.3 | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 10.6 ± 5.5 |

| Skin hyperemic response (%)c | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 1077.2 ± 731.2 | 1219.5 ± 804.7 | 1083.5 ± 763.6 | 1064.5 ± 743.2 | 1204.7 ± 771.1 | 1118.8 ± 799.0 |

| Median [interquartile range] | 960.6 [570.8‐1462.3] | 1074.0 [636.8‐1630.1] | 910.5 [575.4‐1407.2] | 960.6 [557.8‐1416.5] | 1052.1 [642.7‐1606.4] | 979.0 [585.0‐1464.3] |

| Skin hyperemia during heating (PU)c | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 114.8 ± 58.0 | 116.3 ± 59.0 | 106.3 ± 54.8 | 114.2 ± 58.7 | 115.0 ± 57.5 | 108.8 ± 57.8 |

| Median [interquartile range] | 107.6 [74.9‐140.6] | 103.3 [75.2‐149.8] | 97.0 [68.3‐131.2] | 108.1 [73.6‐138.5] | 102.3 [73.8‐148.0] | 98.7 [70.0‐133.0] |

| Baseline arteriolar diameter before flicker light exposure (MU)b | 116.3 ± 16.6 | 115.3 ± 16.8 | 116.2 ± 16.0 | 115.6 ± 15.8 | 114.6 ± 16.0 | 115.5 ± 15.2 |

| Arteriolar average dilation (%)b | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.2 ± 3.0 | 3.0 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 2.8 | 3.2 ± 2.9 | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 3.0 ± 2.7 |

| Median [interquartile range] | 2.7 [1.0‐5.2] | 2.6 [0.9‐4.7] | 2.4 [0.8‐4.4] | 2.8 [1.0‐5.1] | 2.8 [0.9‐5.1] | 2.6 [0.9‐4.8] |

| Arteriolar diameter during flicker light exposure (MU)b | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 119.9 ± 16.8 | 118.7 ± 16.8 | 119.5 ± 16.1 | 119.2 ± 15.9 | 118.1 ± 16.0 | 118.9 ± 15.4 |

| Median [interquartile range] | 119.5 [107.9‐129.4] | 118.0 [105.9‐128.3] | 119.4 [107.9‐129.4] | 118.3 [107.9‐129.2] | 118.2 [107.3‐127.9] | 119.0 [108.1‐128.8] |

| Accelerometry variables | ||||||

| Valid worn days | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 1.2 |

| Waking time (h/day) | 16.0 ± 0.8 | 15.7 ± 0.9 | 15.4 ± 1.0 | 15.9 ± 0.8 | 15.8 ± 0.9 | 15.5 ± 1.0 |

| Total physical activity (h/day) | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| Higher‐intensity physical activity (h/day) | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| Sedentary time (h/day) | 8.5 ± 1.4 | 9.5 ± 1.5 | 10.6 ± 1.4 | 8.3 ± 1.4 | 9.4 ± 1.4 | 10.5 ± 1.5 |

Data are reported as mean ± SD, median [interquartile range], or number (percentages %) as appropriate.

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

(Micro)albuminuria was defined as a urinary albumin excretion of >30 mg per 24 hours.

In the skin study population, flicker light‐induced retinal arteriolar reactivity measures were available in n = 952.

In the retinal study population, heat‐induced skin hyperemia measures were available in n = 952.

3.2. Associations of total and higher‐intensity physical activity with skin hyperemia and retinal arteriolar dilation

In adjusted analyses, total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity were not significantly associated with heat‐induced skin hyperemia (Table 2). However, the associations between total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity with heat‐induced skin hyperemia differed between individuals without and with T2D (P interactions < 0.10, Table 2). In individuals without T2D, total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity were not significantly associated with heat‐induced skin hyperemia. In contrast, in individuals with T2D, total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity were directly associated with heat‐induced skin hyperemia (regression coefficients per hour increase were 10 PU (95% CI: 1; 18, P = .026) and 36 PU (14; 58, P = .002), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable‐adjusted associations of total physical activity, higher‐intensity physical activity, and total sedentary time with heat‐induced skin hyperemia in the total skin study population and stratified according to T2D status

| Heat‐induced skin hyperemia (PU) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3a | Model 3b | Pinteraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | ||

| Total skin study population (n = 1298) | |||||

| Total physical activity (h/day) | 2 (−3; 7) | 1 (−4; 6) | — | — | — |

| Higher‐intensity physical activity (h/day) | 6 (−5; 17) | 3 (−9; 14) | 4 (−8; 16) | — | — |

| Total sedentary time (h/day) | 0 (−2; 2) | 1 (−1; 3) | — | 1 (−1; 3) | — |

| Without T2D (n = 915) | |||||

| Total physical activity (h/day) | −2 (−8; 4) | −3 (−9; 3) | — | — | — |

| Higher‐intensity physical activity (h/day) | −3 (−16; 10) | −6 (−20; 7) | −3 (−17; 11) | — | — |

| Total sedentary time (h/day) | 2 (−1; 4) | 2 (−1; 5) | — | 2 (−1; 5) | — |

| With T2D (n = 383) | |||||

| Total physical activity (h/day) | 11 (4; 19) | 10 (1; 18) | — | — | 0.018 |

| Higher‐intensity physical activity (h/day) | 40 (20; 61) | 38 (16; 60) | 36 (14; 58) | — | 0.001 |

| Total sedentary time (h/day) | −3 (−6; −0) | −2 (−6; 1) | — | −1 (−5; 2) | 0.068 |

Regression results are presented as unstandardized coefficients (B) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Boldface indicates statistical significance (P < .05).

P interaction (with T2D) was based on model 2.

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, glucose metabolism status (for “total skin study population” only), waking time, and baseline skin blood flow. For analyses in individuals without T2D, model 1 is also adjusted for prediabetes status.

Model 2: additionally adjusted for educational level, body mass index, mobility limitation, office systolic blood pressure, total‐to‐HDL cholesterol ratio, triglycerides, antihypertensive and lipid‐modifying medication, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and a history of CVD.

Model 3a: additionally adjusted for sedentary time.

Model 3b: additionally adjusted for higher‐intensity physical activity.

In adjusted analyses, total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity were not significantly associated with flicker light‐induced retinal arteriolar %‐dilation (Table 3). In addition, the associations between total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity with retinal arteriolar %‐dilation did not differ significantly between individuals without and with T2D (P interactions > 0.10, Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable‐adjusted associations of total physical activity, higher‐intensity physical activity, and total sedentary time with retinal arteriolar %‐dilation

| Retinal arteriolar dilation (%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3a | Model 3b | P interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95%CI) | B (95%CI) | B (95%CI) | B (95%CI) | ||

| Total physical activity (hour/d) | −0.04 (−0.24; 0.15) | −0.09 (−0.30; 0.11) | — | — | 0.814 |

| Higher‐intensity physical activity (hour/d) | −0.16 (−0.60; 0.27) | −0.24 (−0.69; 0.22) | −0.24 (−0.71; 0.23) | — | 0.226 |

| Total sedentary time (hour/d) | 0.01 (−0.09; 0.08) | 0.01 (−0.08; 0.10) | — | −0.00 (−0.09; 0.09) | 0.806 |

Regression results are presented as unstandardized coefficients (B) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

Boldface indicates statistical significance (P < .05).

Pinteraction (with T2D) was based on model 2.

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, glucose metabolism status, and waking time.

Model 2: additionally adjusted for educational level, body mass index, mobility limitation, office systolic blood pressure, total‐to‐HDL cholesterol ratio, triglycerides, antihypertensive and lipid‐modifying medication, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and a history of CVD.

Model 3a: additionally adjusted for sedentary time.

Model 3b: additionally adjusted for higher‐intensity physical activity.

3.3. Associations of sedentary behavior with skin hyperemia and retinal arteriolar dilation

In adjusted analyses, total sedentary time was not associated with heat‐induced skin hyperemia (Table 2). Although associations between total sedentary time and heat‐induced skin hyperemia differed statistically between individuals without and with T2D (P interaction < 0.10), stratified analyses in individuals without and with T2D did not show significant associations between total sedentary time and heat‐induced skin hyperemia (Table 2).

In adjusted analyses, total sedentary time was not significantly associated with flicker light‐induced retinal arteriolar %‐dilation (Table 3). In addition, the association between total sedentary time and retinal arteriolar %‐dilation did not differ significantly between individuals without and with T2D (Pinteraction > 0.10, Table 3).

3.4. Additional analyses

As associations of total physical activity and higher‐intensity physical activity with heat‐induced skin hyperemia were stronger in individuals with as compared to those without T2D, we further explored interactions between continuous measures of glycemia (ie, HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, and 2‐h postload glucose) and total and higher‐intensity physical activity. Statistically significant interactions were found between 2‐h postload glucose and total physical activity, and between HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, and 2‐h postload glucose and higher‐intensity physical activity (all P interactions < 0.10; data not shown). In individuals with prediabetes, regression coefficients of the associations of total and higher‐intensity physical activity with skin hyperemia were numerically in between those of individuals without and with T2D (Table S5).

Qualitatively similar associations of total physical activity, higher‐intensity physical activity, and total sedentary time with skin hyperemia and retinal arteriolar %‐dilation were observed in a range of additional analyses: first, when heat‐induced increase in skin blood flow (in PU) from skin baseline or flicker light‐induced increase (in MU) in retinal arteriolar diameter from baseline were used as outcomes (data not shown); second, when substituting office systolic blood pressure for 24‐h ambulatory systolic blood pressure (data not shown, for skin and retinal analyses, 24‐h ambulatory blood pressure was available in n = 1151 individuals (n = 812 without and n = 339 with T2D) and n = 1632 (n = 1180 without and n = 452 with T2D) respectively); third, after additional adjustment for daily caloric intake (data not shown, for skin and retinal analyses, daily caloric intake was available in n = 1219 individuals (n = 863 without and n = 356 with T2D) and n = 1755 (n = 1276 without and n = 479 with T2D) respectively) or occupational status (data not shown, for skin and retinal analyses, occupational status was available in n = 1122 individuals (n = 807 without and n = 315 with T2D) and n = 1609 (n = 1178 without and n = 431 with T2D) respectively); fourth, after additional adjustment for eGFR, urinary albumin excretion, and the presence of retinopathy (data not shown, for skin and retinal analyses, data on these additional covariates were available in n = 1163 individuals (n = 809 without and n = 354 with T2D) and n = 1774 (n = 1288 without and n = 486 with T2D) respectively); fifth, when antihypertensive medication was further specified into renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system (RAAS)‐inhibiting (with or without other types of antihypertensives) and non‐RAAS‐inhibiting antihypertensives only (data not shown; RAAS‐inhibiting antihypertensives included angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme, angiotensin receptor blockers, and renin blockers); sixth, after additional adjustment for time of the day or month of the year when the skin and retinal measurements were done (to adjust for possible diurnal or seasonal influences; data not shown); and seventh, associations of total physical activity, higher‐intensity physical activity, and total sedentary time with skin hyperemia and retinal arteriolar %‐dilation did not differ between women and men or by age (all Pinteractions > 0.10). Last, collinearity diagnostics revealed no problematic multicollinearity in any of the analyses (ie, all tolerance values ≥ 0.10 and variance inflation factors ≤ 10).

4. DISCUSSION

In this population‐based study, we tested the hypothesis that habitually low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary time (objectively quantified with an accelerometer) can affect microvascular endothelial function. There were three novel findings. First, higher levels of total and higher‐intensity physical activity were independently associated with greater skin microvascular vasodilation in individuals with, but not in those without, T2D. Second, and in contrast to our hypothesis, sedentary time was not associated with skin microvascular function. Third, physical activity and sedentary behavior were not statistically significantly associated with retinal microvascular function. These findings suggest that increasing habitual daily physical activity should be investigated as a means to improving microvascular function in T2D, with the ultimate goal of reducing risk of heart failure,1 (lacunar) stroke,2 depression,3 cognitive decline,4 retinopathy,6 chronic kidney disease,5 and neuropathy.6

Both heat‐induced skin hyperemia and flicker light‐induced retinal arteriolar dilation are likely a reflection of microvascular endothelial function, as they both rely on nitric oxide bioavailability,51, 52 possibly in conjunction 53with vascular smooth muscle cell function,54, 55 and/or neuronal function.56, 57 Mechanistically, higher levels of physical activity and lower levels of sedentary time are thought to increase nitric oxide bioavailability.29, 30 On the one hand, physical activity is thought to induce microvascular laminar shear stress and thereby stimulate the synthesis of nitric oxide by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS).58 On the other hand, physical activity is thought to inhibit eNOS uncoupling via reduction of oxidative stress by improvement of insulin sensitivity.58

The associations of higher levels of total and higher‐intensity physical activity with greater heat‐induced skin hyperemia in individuals with T2D are in agreement with findings from priorhuman and animal research.53, 59, 60 As in individuals with T2D insulin sensitivity is thought to be worse, a likely explanation for stronger associations in T2D is that in T2D physical activity improves nitric oxide bioavailability via both stimulation of eNOS and inhibition of eNOS uncoupling.58 Alternatively, as in individuals NGM insulin sensitivity is not reduced, the effect of physical activity on nitric oxide bioavailability may be less strong because under normal glycemic circumstances physical activity is thought to mostly improve nitric oxide bioavailability via stimulation of eNOS.58

The absence of an association between higher levels of habitual total and higher‐intensity physical activity and greater skin microvascular function in individuals without T2D contrasts with earlier studies which showed beneficial effects of (chronic) intensive exercise on skin microvascular function in healthy individuals.61 A possible explanation is that in individuals without T2D, physical activity‐induced improvement in skin microvascular function is observed only at higher intensities and longer duration of physical activity than those in our study.20, 61

The absence of an inverse association between higher levels of habitual total sedentary time and skin microvascular function contrasts with earlier studies with uninterrupted sedentary time protocols.19, 25, 26 Mechanistically, sedentary behavior is thought to reduce shear stress, leading to less nitric oxide synthesis and reduced endothelium‐dependent vasodilation.29 Insufficient duration of total sedentary time (mean ± SD: 9.5 ± 1.7 hour/d; range: 2.5 to 15.9 hour/d) is unlikely to explain the absence of an inverse association between sedentary behavior and microvascular function. A likelier explanation is that frequent transient interruptions of sedentary behavior by standing and/or walking can restore sedentary behavior‐induced microvascular dysfunction,19, 25 presumably via changes in shear stress.62 Indeed, a higher number of such interruptions, which in our study population occurred on average ~ 4 times per sedentary hour, have been shown to be associated with reduced cardiovascular mortality.63

Autoregulation of retinal blood flow can explain why physical activity and sedentary behavior were not associated with retinal microvascular function.39, 40, 64 During physical activity, constriction of small retinal arterioles increases retinal vascular resistance in proportion to the increase in ocular perfusion pressure40 to stabilize retinal perfusion,39, 40 presumably to maintain visual acuity.41 Our finding of a numerically lower baseline retinal arteriolar diameter with increased levels of higher‐intensity physical activity (Table S4) is consistent with this interpretation. Whether chronic habitual sedentary behavior alters ocular blood flow is currently unknown, but unlikely, as retinal autoregulation has been shown to preserve stable retinal perfusion during transient sedentary time at different postures (eg, sitting and lying).64

Strengths of our study include its size and population‐based design; the use of a waterproof‐attached accelerometer, which has resulted in improved wear time compliance,65 and measures which are more precise and valid than when self‐reported28; the extensive assessment of, and adjustment for, potential confounders; the use of two independent methods to directly assess microvascular function in different microvascular beds; and the broad array of additional analyses, which all gave consistent results.

Our study had some limitations. First, the data were cross‐sectional. Therefore, we cannot exclude reverse causality, that is, that microvascular dysfunction leads to suboptimal delivery of oxygen and nutrients to tissues (eg, muscle) on demand and therefore may hamper physical activity. Second, total and higher‐intensity physical activity and total sedentary time were measured during one week, which may not truly reflect habitual behavior. However, with an average wear time of 6.2 days in our study, compliance to the 8‐day wear time protocol was good, and sufficient to reliably estimate habitual sedentary behavior and close to optimal wear time for estimation of habitual physical activity.66 Third, higher‐intensity physical activity was based on step frequency, which is less precise than acceleration‐based determination. However, we used a cutoff point of > 110 steps/minute for higher‐intensity physical activity, which roughly equals a metabolic equivalent of task (MET) score of ≥ 3.0 (which indicates moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity activity).47 Last, although we adjusted for many potential confounders, we cannot fully exclude residual confounding by variables not included in these analyses (eg, dietary habits).

This large population‐based study, with postured‐based accelerometry data, showed that higher levels of total and higher‐intensity physical activity were independently associated with greater skin microvascular vasodilation in individuals with, but not in those without, T2D. This is consistent with beneficial effects of physical activity on nitric oxide bioavailability, which are likely more prominent in individuals with hyperglycemia. These findings suggest that increasing habitual daily physical activity should be investigated as a means to improving microvascular function in T2D, with the ultimate goal of reducing risk of heart failure,1 (lacunar) stroke,2 depression,3 cognitive decline,4 chronic kidney disease,5 and neuropathy.6

5. PERSPECTIVE

In this large population‐based study, with postured‐based accelerometry data, higher levels of total and higher‐intensity physical activity were independently associated with greater skin microvascular vasodilation in individuals with T2D. However, physical activity was not associated with retinal microvascular dilatation response. Habitual daily physical activity should be investigated as a means to improving microvascular function in T2D, with the ultimate goal of reducing risk of heart failure, (lacunar) stroke, depression, cognitive decline, chronic kidney disease, and neuropathy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

BMS and FCTH contributed to conception and design, participated in acquisition of data, analyzed and interpreted data, drafted the manuscript (with CDAS), revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. BMS and FCTH also are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. TJMB, JSAGS, AAK, CJHvd.K., RMAH, AK, HHCMS, MCJMv.D., SJPME, JDvd.B., PCD, and NCS contributed to conception and design, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. AJHMH, MTS, and CDAS contributed to conception and design, contributed to analyses and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge ZIO foundation (Vereniging Regionale HuisartsenZorg Heuvelland) for their contribution to The Maastricht Study. The researchers are indebted to the participants for their willingness to participate in the study.

Sörensen BM, van der Heide FCT, Houben AJHM, et al. Higher levels of daily physical activity are associated with better skin microvascular function in type 2 diabetes—The Maastricht Study. Microcirculation. 2020;27:e12611 10.1111/micc.12611

Ben M. Sörensen and Frank CT van der Heide contributed equally to this work.

Funding information

This study was supported by the European Regional Development Fund via OP‐Zuid, the Province of Limburg, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs (grant 31O.041), Stichting De Weijerhorst (Maastricht, the Netherlands), the Pearl String Initiative Diabetes (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), the Cardiovascular Center (CVC, Maastricht, the Netherlands), CARIM School for Cardiovascular Diseases (Maastricht, the Netherlands), CAPHRI School for Public Health and Primary Care (Maastricht, the Netherlands), NUTRIM School for Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism (Maastricht, the Netherlands), Stichting Annadal (Maastricht, the Netherlands), Health Foundation Limburg (Maastricht, the Netherlands), Perimed (Järfälla, Sweden), Diabetesfonds (Amersfoort, The Netherlands) (grant 2016.22.1878), and Oogfonds (Utrecht, The Netherlands) and by unrestricted grants from Janssen‐Cilag BV (Tilburg, the Netherlands), Novo Nordisk Farma BV (Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands), and Sanofi‐Aventis Netherlands BV (Gouda, the Netherlands).

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee JF, Barrett‐O'Keefe Z, Garten RS, et al. Evidence of microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart. 2016;102:278‐284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knottnerus IL, Ten Cate H, Lodder J, Kessels F, van Oostenbrugge RJ. Endothelial dysfunction in lacunar stroke: a systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:519‐526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Santos M, Xekardaki A, Kovari E, Gold G, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Microvascular pathology in late‐life depression. J Neurol Sci. 2012;322:46‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De Silva TM, Faraci FM. Microvascular Dysfunction and Cognitive Impairment. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36:241‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zafrani L, Ince C. Microcirculation in Acute and Chronic Kidney Diseases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:1083‐1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gupta A, Bhatnagar S. Vasoregression: A Shared Vascular Pathology Underlying Macrovascular And Microvascular Pathologies? OMICS. 2015;19:733‐753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:405‐412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, et al. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) – Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN. Katzmarzyk PT and Lancet Physical Activity Series Working G. Effect of physical inactivity on major non‐communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219‐229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen SM, Tsai TH, Hang CL, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in young patients with acute ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels. 2011;26:2‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Witte DR, Westerink J, de Koning EJ, van der Graaf Y, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. Is the association between flow‐mediated dilation and cardiovascular risk limited to low‐risk populations? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1987‐1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Young DR, Reynolds K, Sidell M, et al. Effects of physical activity and sedentary time on the risk of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:21‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Willey JZ, Moon YP, Sacco RL, et al. Physical inactivity is a strong risk factor for stroke in the oldest old: Findings from a multi‐ethnic population (the Northern Manhattan Study). Int J Stroke. 2017;12:197‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schuch F, Vancampfort D, Firth J, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:139‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steinberg SI, Sammel MD, Harel BT, et al. Exercise, sedentary pastimes, and cognitive performance in healthy older adults. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30:290‐298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Praidou A, Harris M, Niakas D, Labiris G. Physical activity and its correlation to diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:456‐461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. White SL, Dunstan DW, Polkinghorne KR, Atkins RC, Cass A, Chadban SJ. Physical inactivity and chronic kidney disease in Australian adults: the AusDiab study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;21:104‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singleton JR, Smith AG, Marcus RL. Exercise as Therapy for Diabetic and Prediabetic Neuropathy. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Restaino RM, Holwerda SW, Credeur DP, Fadel PJ, Padilla J. Impact of prolonged sitting on lower and upper limb micro‐ and macrovascular dilator function. Exp Physiol. 2015;100:829‐838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tew GA, George KP, Cable NT, Hodges GJ. Endurance exercise training enhances cutaneous microvascular reactivity in post‐menopausal women. Microvasc Res. 2012;83:223‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roche DM, Rowland TW, Garrard M, Marwood S, Unnithan VB. Skin microvascular reactivity in trained adolescents. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1201‐1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang JS. Effects of exercise training and detraining on cutaneous microvascular function in man: the regulatory role of endothelium‐dependent dilation in skin vasculature. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;93:429‐434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Navasiolava NM, Dignat‐George F, Sabatier F, et al. Enforced physical inactivity increases endothelial microparticle levels in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H248‐H256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vranish JR, Young BE, Kaur J, Patik JC, Padilla J, Fadel PJ. Influence of sex on microvascular and macrovascular responses to prolonged sitting. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H800‐H805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Demiot C, Dignat‐George F, Fortrat JO, et al. WISE 2005: chronic bed rest impairs microcirculatory endothelium in women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3159‐H3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamburg NM, McMackin CJ, Huang AL, et al. Physical inactivity rapidly induces insulin resistance and microvascular dysfunction in healthy volunteers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2650‐2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anuradha S, Dunstan DW, Healy GN, et al. Physical activity, television viewing time, and retinal vascular caliber. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:280‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Downs A, Van Hoomissen J, Lafrenz A, Julka DL. Accelerometer‐measured versus self‐reported physical activity in college students: implications for research and practice. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62:204‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thosar SS, Johnson BD, Johnston JD, Wallace JP. Sitting and endothelial dysfunction: the role of shear stress. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:RA173‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nyberg M, Blackwell JR, Damsgaard R, Jones AM, Hellsten Y, Mortensen SP. Lifelong physical activity prevents an age‐related reduction in arterial and skeletal muscle nitric oxide bioavailability in humans. J Physiol. 2012;590:5361‐5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lambert CP, Wright NR, Finck BN, Villareal DT. Exercise but not diet‐induced weight loss decreases skeletal muscle inflammatory gene expression in frail obese elderly persons. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2008(105):473‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parsons TJ, Sartini C, Welsh P, et al. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Inflammatory and Hemostatic Markers in Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:459‐465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matlung HL, Bakker EN, VanBavel E. Shear stress, reactive oxygen species, and arterial structure and function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1699‐1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamed S, Brenner B, Roguin A. Nitric oxide: a key factor behind the dysfunctionality of endothelial progenitor cells in diabetes mellitus type‐2. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:9‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sorensen BM, Houben A, Berendschot T, et al. Hyperglycemia Is the Main Mediator of Prediabetes‐ and Type 2 Diabetes‐Associated Impairment of Microvascular Function: The Maastricht Study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:e103‐e105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nguyen TT, Kreis AJ, Kawasaki R, et al. Reproducibility of the retinal vascular response to flicker light in Asians. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34:1082‐1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Agarwal SC, Allen J, Murray A, Purcell IF. Comparative reproducibility of dermal microvascular blood flow changes in response to acetylcholine iontophoresis, hyperthermia and reactive hyperaemia. Physiol Meas. 2010;31:1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kenny GP, McGinn R. Restoration of thermoregulation after exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2017(122):933‐944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayashi N, Ikemura T, Someya N. Effects of dynamic exercise and its intensity on ocular blood flow in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:2601‐2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Risner D, Ehrlich R, Kheradiya NS, Siesky B, McCranor L, Harris A. Effects of exercise on intraocular pressure and ocular blood flow: a review. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:429‐436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hayashi N, Someya N, Ikemura T. Effects of hyper‐ and hypocapnea on choroidal and retinal blood flows and the visual acuity. Faseb J. 2010;24. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schram MT, Sep SJ, van der Kallen CJ, et al. The Maastricht Study: an extensive phenotyping study on determinants of type 2 diabetes, its complications and its comorbidities. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:439‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sorensen BM, Houben AJ, Berendschot TT, et al. Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Are Associated With Generalized Microvascular Dysfunction: The Maastricht Study. Circulation. 2016;134:1339‐1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vickers AJ. The use of percentage change from baseline as an outcome in a controlled trial is statistically inefficient: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001;1:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Atkinson G, Batterham AM. The percentage flow‐mediated dilation index: a large‐sample investigation of its appropriateness, potential for bias and causal nexus in vascular medicine. Vasc Med. 2013;18:354‐365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van der Berg JD, Willems PJ, van der Velde JH, et al. Identifying waking time in 24‐h accelerometry data in adults using an automated algorithm. J Sports Sci. 2016;34:1867‐1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tudor‐Locke C, Craig CL, Brown WJ, et al. How many steps/day are enough? For adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:79.21798015 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tudor‐Locke C, Rowe DA. Using cadence to study free‐living ambulatory behaviour. Sports Med. 2012;42:381‐398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tremblay MS, Colley RC, Saunders TJ, Healy GN, Owen N. Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35:725‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martens RJ, Henry RM, Houben AJ, et al. Capillary Rarefaction Associates with Albuminuria: The Maastricht Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3748‐3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kellogg DL Jr, Liu Y, Kosiba IF, O'Donnell D. Role of nitric oxide in the vascular effects of local warming of the skin in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1999(86):1185‐1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dorner GT, Garhofer G, Kiss B, et al. Nitric oxide regulates retinal vascular tone in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H631‐H636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mitranun W, Deerochanawong C, Tanaka H, Suksom D. Continuous vs interval training on glycemic control and macro‐ and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:e69‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Montero D, Pierce GL, Stehouwer CD, Padilla J, Thijssen DH. The impact of age on vascular smooth muscle function in humans. J Hypertens. 2015;33:445‐453; discussion 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lacolley P, Regnault V, Nicoletti A, Li Z, Michel JB. The vascular smooth muscle cell in arterial pathology: a cell that can take on multiple roles. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:194‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Minson CT, Berry LT, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide and neurally mediated regulation of skin blood flow during local heating. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2001(91):1619‐1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Falsini B, Riva CE, Logean E. Flicker‐evoked changes in human optic nerve blood flow: relationship with retinal neural activity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2309‐2316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Meza CA, La Favor JD, Kim DH, Hickner RC. Endothelial Dysfunction: Is There a Hyperglycemia‐Induced Imbalance of NOX and NOS? Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Green DJ, Maiorana A, O'Driscoll G, Taylor R. Effect of exercise training on endothelium‐derived nitric oxide function in humans. J Physiol. 2004;561:1‐25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Machado MV, Martins RL, Borges J, et al. Exercise Training Reverses Structural Microvascular Rarefaction and Improves Endothelium‐Dependent Microvascular Reactivity in Rats with Diabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2016;14:298‐304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lanting SM, Johnson NA, Baker MK, Caterson ID, Chuter VH. The effect of exercise training on cutaneous microvascular reactivity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:170‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tinken TM, Thijssen DH, Hopkins N, et al. Impact of shear rate modulation on vascular function in humans. Hypertension. 2009;54:278‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Diaz KM, Howard VJ, Hutto B, et al. Patterns of Sedentary Behavior and Mortality in U.S. Middle‐Aged and Older Adults: A National Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Feke GT, Pasquale LR. Retinal blood flow response to posture change in glaucoma patients compared with healthy subjects. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:246‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tudor‐Locke C, Barreira TV, Schuna JM Jr, et al. Improving wear time compliance with a 24‐hour waist‐worn accelerometer protocol in the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Barreira TV, Hamilton MT, Craft LL, Gapstur SM, Siddique J, Zderic TW. Intra‐individual and inter‐individual variability in daily sitting time and MVPA. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19:476‐481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials