Abstract

Complete and accurate registration of cancer is needed to provide reliable data on cancer incidence and to investigate aetiology. Such data can be derived from national cancer registries, but also from large population‐based cohort studies. Yet, the concordance and discordance between these two data sources remain unknown. We evaluated completeness and accuracy of cancer registration by studying the concordance between the population‐based Rotterdam Study (RS) and the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) between 1989 and 2012 using the independent case ascertainment method. We compared all incident cancers in participants of the RS (aged ≥45 years) to registered cancers in the NCR in the same persons based on the date of diagnosis and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code. In total, 2,977 unique incident cancers among 2,685 persons were registered. Two hundred eighty‐eight cancers (9.7%) were coded by the RS that were not present in the NCR. These were mostly nonpathology‐confirmed lung and haematological cancers. Furthermore, 116 cancers were coded by the NCR, but not by the RS (3.9%), of which 20.7% were breast cancers. Regarding pathology‐confirmed cancer diagnoses, completeness was >95% in both registries. Eighty per cent of the cancers registered in both registries were coded with the same date of diagnosis and ICD code. Of the remaining cancers, 344 (14.5%) were misclassified with regard to date of diagnosis and 72 (3.0%) with regard to ICD code. Our findings indicate that multiple sources on cancer are complementary and should be combined to ensure reliable data on cancer incidence.

Keywords: epidemiology, cancer registration, cohort studies, accuracy, misclassification

Short abstract

What's new?

While national cancer registries and population‐based cohort studies are the primary sources of data on cancer risk and incidence, the degree to which these data sets are concordant remains unknown. In this investigation, the authors evaluated concordance between the population‐based Rotterdam Study and the Netherlands Cancer Registry. The two data sets were highly concordant for pathology‐confirmed cancers and cancer site. Non‐pathology‐confirmed cancers, however, were under‐registered in the Netherlands Cancer Registry, potentially resulting in underestimation of cancer incidence. The findings highlight the important role that different sources of cancer diagnosis registration serve in providing reliable estimates of cancer incidence.

Abbreviations

- DCIS

ductal carcinoma in situ

- ICD

International Classification of Disease

- IKNL

Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation

- IQR

interquartile range

- LMR

Landelijke Medische Registratie

- NCR

Netherlands Cancer Registry

- PSA

prostate‐specific antigen

- RS

Rotterdam Study

- SD

standard deviation

Introduction

With an estimated number of 3.9 million new diagnoses and 1.9 million deaths from cancer in Europe in 2018, cancer poses a huge burden on societies.1 Optimal cancer registration is not only crucial to provide reliable estimations of incidence and mortality,2 but is also pivotal to better understand risk factors of cancer.3 Extensive quality checks are performed before cancer registry data are accepted in Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, the reference source of data on international cancer incidence.4 However, the number of validation studies of cancer registries is limited.

Methods to assess completeness and accuracy of cancer registries can be classified into two categories, that is, qualitative and quantitative methods.5 Qualitative methods include comparison of the performance of a cancer registry with other registries, such as comparison with historical data or other populations. In contrast to qualitative methods, quantitative methods including independent case ascertainment, flow method, or capture‐recapture methods provide a numerical evaluation of the extent to which all eligible events are registered and are therefore more appealing.

Several studies have compared cancer registries in Europe using quantitative methods.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 In the Netherlands, the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) managed by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) registers cancers nationwide and provides information regarding cancer incidence, prevalence, risk, mortality and survival of cancer.18 Completeness of registration by the NCR has been estimated at 98.7% in 1990 based on cancers registered by general practitioners.6 A second evaluation in 1993 showed completeness of 96.2%.7 However, the potential added value of a large prospective population‐based cohort study to the completeness and accuracy of cancer registration by the national cancer registry has not been evaluated.

Therefore, in our study, we investigated the concordance of cancer registration by the NCR with a large population‐based cohort study, the Rotterdam Study (RS).

Materials and Methods

Setting

Our study is embedded within the RS, an ongoing population‐based cohort study in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, designed to study the occurrence and determinants of age‐related diseases. Besides cancer, the RS focuses on the aetiology, prediction and prognosis of cardiovascular, endocrine, hepatic, neurological, ophthalmologic, psychiatric, dermatological, otolaryngologic, locomotor and respiratory diseases. The RS started in 1990 with 7,983 participants (response of 78%) aged ≥55 years and residing in the district Ommoord, a suburb of Rotterdam. This first subcohort (RS‐I) was extended with a second subcohort (RS‐II) in 2000, consisting of 3,011 participants (response of 67%) and with a third subcohort (RS‐III) in 2006, composed of 3,932 participants aged ≥45 years (response of 65%). The design of the RS has been described in detail.19 In total, the RS comprises 14,926 participants aged ≥45 years at study entry.

The RS has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Erasmus Medical Center and by the board of The Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. A written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Assessment of cancer

The Rotterdam Study

Diagnosis of incident cancer is based on medical records of general practitioners (including hospital discharge letters) and furthermore through linkage with the national hospital discharge registry (Landelijke Medische Registratie [LMR]) hosted by Dutch Hospital Data and histology and cytopathology registries in the region (part of the nationwide network PALGA). Cancer diagnosis is coded independently by two physicians and classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD‐10). In case of discrepancy between sources, consensus is sought through consultation with a physician specialised in internal medicine. Date of diagnosis is based on the pathology date, or—if unavailable—date of hospital admission or hospital discharge letter. Level of uncertainty of diagnosis is established as certain (pathology‐confirmed), probable (e.g., based on imaging features or elevated tumour markers without pathological confirmation) and possible (e.g., based on symptoms and physical examination or suspicion based on imaging features or elevated tumour markers without pathological confirmation). Possible cancers were not included in the current study. Registration of cancer diagnoses is completed up to January 1, 2013.

The Netherlands Cancer Registry

The NCR is a population‐based cancer registry with nationwide coverage since 1989. Cancer diagnoses are notified by the nationwide network and registry of histology and cytopathology (PALGA) and in addition through linkage with the LMR hosted by Dutch Hospital Data. Each cancer is coded by trained registration clerks (internal education of 1 year) according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD‐O‐3) based on information gathered from medical files at the hospital. Date of diagnosis is coded according to international coding rules and mostly based on the date of first pathological confirmation, or—if unavailable—date of first hospital admission. In addition, information about tumour histology, tumour stage and primary treatment was retrieved.

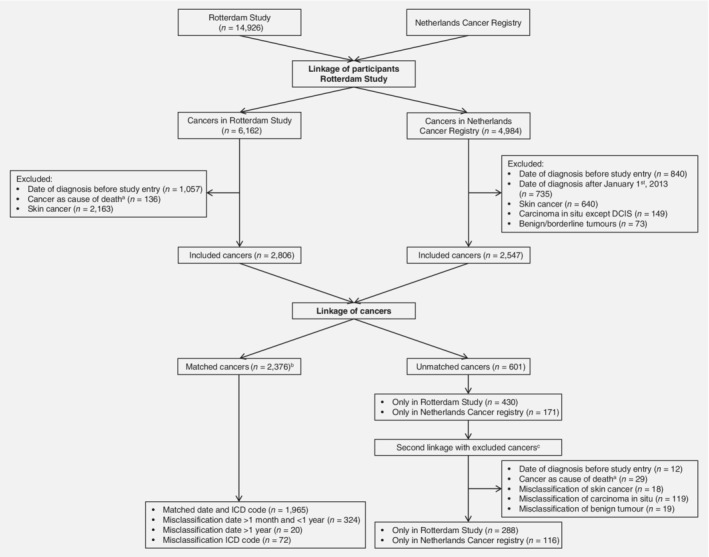

Linkage

All persons from the RS (n = 14,926) were linked with patients in the NCR based on the following characteristics: date of birth, sex, birth name, initials, zip code and—if applicable—date of death. If a participant had multiple zip codes due to moving, historical zip codes were also included. All data were pseudonymised using a double‐pass procedure beforehand. Data exchange took place between secured encrypted data servers. All cancers diagnosed between 1989 and 2012 were included. To make an equal comparison between the two cancer registries, we excluded the following cancers: cancers diagnosed before entry in the RS or after January 1, 2013, cancers solely coded as cause of death, skin cancers (due to different registration methods), benign or borderline tumours and carcinomas in situ other than ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast (Fig. 1). If a cancer was only coded by the RS or the NCR (unmatched cancers), we performed a second linkage with previously excluded cancers (that is for instance, date of diagnosis prior to study entry or cancer solely registered as cause of death). In case of multiple cancers per patient, we included all different cancers.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of matched and unmatched cancers after linkage between the Rotterdam Study and Netherlands Cancer Registry. Abbreviations: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ICD, International Classification of Diseases. aCancer as cause of death corresponds to cancer solely coded as cause of death, without a date of incident cancer diagnosis. bFive cancers were both misclassified with regard to date >1 month and <1 year and with regard to ICD code. Therefore, the number of matched cancers is lower than the total number of cancers in the different misclassification categories. cA second linkage was performed to preclude whether unmatched cancers were present in both databases, but were excluded prior to the linkage of cancers based on the exclusion criteria.

We were interested in (i) the completeness and (ii) the accuracy of both registries. Since we do not know the true number of cancers in the study population, we defined completeness as the proportion of cancers in one registry in relation to the total number of cancers coded by at least one of the registries. Completeness was determined for pathology‐confirmed diagnoses of cancer and nonpathology‐confirmed diagnoses separately, as well as for all cancers combined.

Accuracy of the date of cancer diagnosis and ICD code was investigated for cancers that were present in both registries (matched cancers). We digitally converted the ICD‐O‐3 codes into ICD‐10 codes. These matched cancers were classified into the following categories: matched date of diagnosis (difference in date of diagnosis of 1 month or less) and ICD code, misclassification of date of diagnosis (two categories: difference in date of diagnosis of more than 1 month but less than 1 year and difference of more than 1 year), or misclassification of ICD code (different ICD code and different organ system). An overview of the different ICD‐10 codes used for the categorisation into different organ systems is presented in Supporting Information Table S1.

Unmatched cancers only coded by the RS and cancers misclassified with regard to the date of diagnosis or ICD code were reassessed through evaluation of the patient's original medical files collected by the RS.

Statistical analyses

Differences in patient characteristics were evaluated using an independent t‐test (continuous variables) or a chi‐squared test (categorical variables). Two‐sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS and the ‘UpSetR’ package from R software Version 3.3.2.20

Results

In the same source population, based on 14,926 participants of the RS, 2,806 incident cancers among 2,579 persons were coded by the RS and 2,547 cancers among 2,342 persons were coded by the NCR (Fig. 1). Linkage of the two registries resulted in a total of 2,977 unique cancers among 2,685 persons.

Completeness of registries

After the first linkage, 2,376 cancers among 2,227 persons were coded by both registries. The remaining 601 unmatched cancers were coded solely by one of the two registries, of which 197 cancers could eventually be matched after a second linkage with previously excluded cancers. This resulted in 288 cancers (9.7%) among 284 persons coded solely by the RS, of which 105 cancers (36.5%) were pathology‐confirmed. Furthermore, 116 cancers (3.9%) among 115 persons were coded solely by the NCR, of which 109 cancers (94.0%) were pathology‐confirmed. Taking only cancers after the second linkage into account, the RS had a completeness of 95.8% (2,664 out of 2,780 cancers) and the NCR of 89.6% (2,492 out of 2,780 cancers) of all cancers. Regarding pathology‐confirmed cancers (2,475 cancers), completeness was 95.3% in the RS and 95.2% in the NCR. Completeness of nonpathology‐confirmed cancers (305 cancers) was 97.7% in the RS and 40.0% in the NCR.

Persons with matched cancer diagnoses were significantly younger at baseline and at first cancer diagnosis than those coded solely by the RS (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively) or by the NCR (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively, Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of persons with matched and unmatched cancers in the Rotterdam Study and the Netherlands Cancer Registry

| Persons with unmatched cancers (n = 397) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Persons with matched cancers (n = 2,227) | Rotterdam study (n = 284) | Netherlands Cancer Registry (n = 115) |

| Age at study entry, years, median (IQR) | 65.1 (11.5) | 71.5 (13.0) | 69.0 (11.8) |

| Sex, women, n (%) | 1,081 (48.5) | 151 (53.2) | 61 (53.0) |

| Education, n (%)1 | |||

| Primary | 395 (17.7) | 69 (24.3) | 22 (19.1) |

| Lower | 897 (40.3) | 104 (36.6) | 43 (37.4) |

| Further | 647 (29.1) | 89 (31.3) | 33 (28.7) |

| Higher | 261 (11.7) | 19 (6.9) | 15 (13.0) |

| Age at first cancer diagnosis, years, n (%) | |||

| 45–65 | 355 (15.9) | 16 (5.6) | 10 (8.7) |

| 65–75 | 856 (38.4) | 50 (17.6) | 27 (23.5) |

| 75–85 | 794 (35.7) | 126 (44.4) | 51 (44.3) |

| >85 | 222 (10.0) | 92 (32.4) | 27 (23.4) |

| Mean (SD) | 74.0 (8.5) | 80.5 (8.6) | 78.2 (9.1) |

Persons in Rotterdam Study or Netherlands Cancer Registry do not sum up to total number of persons with unmatched cancers since some persons with unmatched cancers overlap. Numbers of education are shown without imputation and therefore do not sum up to 100%.

Education levels were assessed during home interviews according to the following categories: primary: primary education, lower: lower/intermediate general education/lower vocational education, intermediate: intermediate vocational education/higher general education or higher: higher vocational education/university.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Cancer sites that were most frequently registered by both registries were gastric and oesophagus (93.4% of all these cancers were included in both registries), head and neck (91.0%) and male genital organs (90.0%, Table 2). Lung and mesothelioma was the most common cancer site among cancers coded solely by the RS (20.5% of all cancer cases solely coded by the RS). Haematological cancer represented the second most frequent diagnosis that was coded solely by the RS (16.0%), of which chronic lymphocytic leukaemia was the most common diagnosis (39.1%). The distribution of different cancer sites among cancers coded solely by the NCR was comparable to the distribution among the matched cancers, with breast as the most frequently diagnosed cancer site (20.7%). One‐third of all cancers solely coded by the NCR were second primary cancers of the same cancer site, with the highest numbers for breast (75.0%) and colon cancers (56.3%).

Table 2.

Overview of cancer sites according to matched and unmatched cancers

| Unmatched cancers (n = 404) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer site | Matched cancers (n = 2,376) | Rotterdam Study (n = 288) | Netherlands Cancer Registry (n = 116) |

| Head and neck | 71 (91.0) | 4 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) |

| Oesophagus and gastric | 141 (93.4) | 5 (3.3) | 5 (3.3) |

| Colorectal | 393 (89.1) | 30 (6.8) | 18 (4.1) |

| Hepato‐Pancreato‐Biliary | 121 (81.2) | 26 (17.4) | 2 (1.3) |

| Lung and mesothelioma | 351 (82.4) | 59 (13.8) | 16 (3.8) |

| Bone and soft tissue | 15 (71.4) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (19.0) |

| Breast | 366 (89.5) | 19 (4.6) | 24 (5.9) |

| Female genital organs | 101 (87.8) | 10 (8.7) | 4 (3.5) |

| Male genital organs | 380 (90.0) | 27 (6.4) | 15 (3.6) |

| Unitary tract | 176 (80.7) | 28 (12.8) | 14 (6.4) |

| Central nervous system | 19 (73.1) | 7 (26.9) | 0 |

| Haematological | 165 (76.7) | 46 (21.4) | 4 (1.9) |

| Other | 21 (67.7) | 4 (12.9) | 6 (19.4) |

| Unknown primary origin | 56 (71.8) | 21 (26.9) | 1 (1.3) |

Numbers are displayed in the total number of cancer site (percentage per row).

Accuracy of registries

One thousand nine hundred sixty‐five cancers out of 2,376 matched cancers (82.7%) were coded with the same date of diagnosis and ICD code by both registries. Most frequent correctly classified cancer sites were colorectal (91.9% of all colorectal cancers), breast (88.3%) and oesophagus and gastric (87.9%). The remaining cancers were misclassified with regard to the date of diagnosis (344 cancers [14.5%]) or ICD code (72 cancers [3.0%]).

Misclassification of date was further divided into a difference in date of diagnosis more than 1 month and less than 1 year (324 cancers), and more than 1 year (20 cancers, Table 3). Male genital cancer with prostate cancer as most frequent cancer was the most common cancer site among cancers with a difference in date of diagnosis of more than 1 month (24.4%) and the second among cancers misclassified for more than 1 year (25.0%), after haematological malignancies (40.0%). Date of diagnosis was more often accurately registered by the NCR than by the RS based on evaluation of the original medical files (Supporting Information Table S2).

Table 3.

Overview of cancer sites according to correctly classified and misclassified cancers

| Misclassified cancers (n = 411)1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer site | Correctly classified cancers (n = 1,965) | Date of diagnosis (n = 344) | ICD code (n = 72) | |

| More than 1 month (n = 324)2 | More than 1 year (n = 20) | |||

| Head and neck | 52 (73.2) | 19 (26.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Oesophagus and gastric | 124 (87.9) | 13 (9.2) | 0 | 4 (2.8) |

| Colorectal | 361 (91.9) | 25 (6.4) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.5) |

| Hepato‐Pancreato‐Biliary | 88 (72.1) | 24 (19.7) | 1 (0.8) | 9 (7.4) |

| Lung and mesothelioma | 291 (82.2) | 41 (11.6) | 2 (0.6) | 20 (5.6) |

| Bone and soft tissue | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Breast | 323 (88.3) | 37 (10.1) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) |

| Female genital organs | 89 (88.1) | 9 (8.9) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Male genital organs | 296 (77.9) | 79 (20.9) | 5 (1.3) | 0 |

| Unitary tract | 136 (76.8) | 38 (21.5) | 0 | 3 (1.7) |

| Central nervous system | 15 (78.9) | 3 (15.8) | 0 | 1 (5.3) |

| Haematological | 130 (78.8) | 27 (16.4) | 8 (4.8) | 0 |

| Other | 10 (47.6) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 10 (47.6) |

| Unknown primary origin | 40 (71.4) | 3 (5.4) | 0 | 13 (23.2) |

Numbers are displayed in total number per cancer site (percentage per row). Cancers misclassified with regard to ICD code are classified according to the different cancer groups based on the ICD code of the Rotterdam Study.

Five cancers were both misclassified with regard to date >1 month and <1 year and with regard to ICD code. Therefore, the number of misclassified cancers is lower than the total number of cancers in the different misclassification categories.

Difference in date of diagnosis more than 1 month and less than 1 year.

Abbreviation: ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Misclassification regarding ICD code was less common, with 72 cancers (3.0%) classified as misclassification of ICD code and organ system (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Most differences in ICD code were found for lung cancers or cancers coded as tumour of unknown primary origin (Supporting Information Fig. S1).

Discussion

In our study, we investigated the concordance of cancers in a prospective population‐based cohort study, the RS, with the NCR. There was a high concordance with regard to pathology‐confirmed cancers (>95%), but the RS registered a higher number of nonpathology‐confirmed cancers. Furthermore, there was a high accuracy with regarding cancer site, but the accuracy with regard to the date of diagnosis was lower in the RS than in the NCR. These findings can help to identify the reasons for inaccurate cancer registration and emphasise that cancer registration by national cancer registries may complement population‐based cohort studies and vice versa.

Completeness varying between 90 and 100% is considered as acceptable to estimate optimal cancer incidence, provided that there are no large differences regarding cancer site or age at cancer diagnosis between registered and unregistered cancers.3 Completeness of pathology‐confirmed cancers was comparable between the RS and the NCR, but we found that the number of nonpathology‐confirmed cancers, with lung and haematological cancers, in particular, were underreported in the NCR. This can be explained by the use of different sources of cancer registration, with the RS having access to the medical records of general practitioners in addition to notification of cancer diagnoses through the pathology database. Regarding the cancers missed by the RS, we observed that one‐third of these cancers were second primary cancers. It is often not well documented in discharge letters whether a second tumour is a recurrent cancer, metastasis or second primary cancer, in contrast to the documentation in medical files in hospitals to which the NCR has access. Although under‐registration of second primary cancers within the same organ will not affect cancer statistics, because these cancers are not included in cancer incidence and survival estimations,21 it may impact aetiological research questions.

Furthermore, we found that cancers coded by solely one registry occurred often in older persons, which has been observed in previous studies as well.2, 6, 22 This observation can be explained because, compared to younger patients, pathological confirmation through biopsies can be limited in elderly patients due to poor clinical condition and prognosis.23, 24, 25 Harms caused by histological tissue acquisition for pathological confirmation without consequences for cancer treatment may outweigh the benefit of knowing the diagnosis in these patients. Furthermore, older patients are less often referred to the hospital and are more likely to be treated (in nursing homes) by their general practitioner.26 Such cancers will remain unnoticed in the NCR, because there is no linkage with general practitioners.

Although the RS had a higher degree of completeness of nonpathology‐confirmed cancers, the accuracy of calendar date of cancer diagnosis was lower compared to the NCR. The RS aims to register the date of cancer diagnosis based on the date of biopsy (solid cancers) or laboratory assessment (haematological cancers). However, this information is not always documented in the hospital discharge letters and other medical files obtained from general practitioners. If the date of pathological confirmation is unavailable, a proxy is taken based on the date of hospital admission or the date of the medical letter. Most discrepancies regarding date of diagnosis were found for male genital organ cancer, mostly represented by prostate cancer, and haematological cancer. Prostate cancer is frequently detected by elevated prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) levels. Since the long‐term benefit of invasive treatment for prostate cancer is questionable,27 treatment options such as watchful waiting and active surveillance are often applied for indolent localised prostate cancer. Monitoring of patients by measuring PSA levels limits the need for pathological confirmation of the cancer in contrast to cancer at other sites. Pathology can be obtained in case of cancer progression, which may occur months after the initial clinical diagnosis. The dates across these different clinical stages are not always accurately documented in medical letters, resulting in misclassification of the date of first diagnosis. Differences in the date of diagnosis of haematological cancers were explained by the different diagnostic examinations on which the date of diagnosis was based (peripheral blood vs. bone marrow biopsy).

In addition, we showed that few of the registered cancers were misclassified with regard to ICD code. We considered cancers with a different ICD code within the same organ system as correctly classified, because part of the misclassification is due to different coding rules. These different coding rules also explain the misclassified cancers with the ICD code for ‘tumour of primary origin’, with the RS being more lenient in coding cancers according to the most probably primary origin. Moreover, cancer diagnoses in the RS are coded independently by two physicians, whereas cancers in the NCR are coded by one trained registration clerk, which could affect the accuracy of registered cancers as well.28

The main strength of our study is the independent case ascertainment method used to study the concordance between a large population‐based cohort study and the nationwide cancer registry. Although the flow method may outperform the independent case ascertainment by having the advantage of measuring completeness during the registration process,5 it does not appropriately describe the data when cancer registration begins with a delay, and is therefore not used in the NCR. Data on cancer diagnoses was collected independently, partly from different sources and with different aims, that is, determining statistics on cancer incidence, prevalence and survival by the NCR while investigating aetiology by the RS. Although these aims are different, optimal cancer registration is fundamental for both purposes. However, it should be noted that the current study is conducted within persons aged ≥45 years and that these findings may differ among a younger population. Furthermore, we cannot rule out that cancers without pathological confirmation are actually benign. However, we classified cancers based on all available medical information, thereby limiting the number of false‐positive diagnoses.

Based on our findings, we have identified the main limitations of both registries, which opens avenues for improvements. Date of diagnosis was misclassified in 11.8% in the RS. Since this information is not always documented in the medical files, we can improve the accuracy by standardised linkage with the NCR. Regarding the NCR, it is of the utmost importance to investigate the reason why some pathology‐confirmed cancers are not captured. Therefore, continuous improvement of registration quality is necessary, especially regarding cancers in elderly and at specific cancer sites such as pancreas, lung and haematological cancers. In addition, many nonpathology‐confirmed cancers were not registered by the NCR. Cancer diagnoses in the NCR are primarily notified by the pathology laboratories and the national hospital discharge registry. However, outpatients are included in the national hospital discharge registry as of 2015, which is expected to improve notification of nonpathology‐confirmed cancers to the NCR. This effect is mainly visible in lung cancer, for which the proportion of nonpathology‐confirmed cancers increased from 8% in 1989–2012 (the inclusion period of our study) to 13% in 2015–2017. Since this misclassification could result in an underestimation of cancer incidence, inclusion of these clinically diagnosed cancers may provide more accurate cancer statistics. However, cancers diagnosed by general practitioners or nursing home physicians without further diagnostics that include pathology or referral to a hospital are still not be captured by the NCR.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that linkage of different cancer registries is needed to improve registration by identifying the reasons of inaccurate cancer registration. Cancer registration by national cancer registries may complement cancer registration by population‐based cohort studies and vice versa. Combination of different sources is needed to provide reliable data on cancer incidence.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all Rotterdam Study participants and staff for their time and commitment to the study. This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number NKI‐20157737). The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University Rotterdam; the Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw); the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE); the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports; the European Commission (DG XII); and the Municipality of Rotterdam. The funding source had no role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report or decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Data availability

Data can be obtained upon request. Requests should be directed toward the management team of the Rotterdam Study (secretariat.epi@erasmusmc.nl), which has a protocol for approving data requests. Because of restrictions based on privacy regulations and informed consent of the participants, data cannot be made freely available in a public repository. The Rotterdam Study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC (registration number MEC 02.1015) and by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (Population Screening Act WBO, license number 1071272‐159521‐PG). The Rotterdam Study has been entered into the Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR; www.trialregister.nl) and into the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp/network/primary/en/) under shared catalogue number NTR6831.

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer 2018;103:356–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fest J, Ruiter R, van Rooij FJ, et al. Underestimation of pancreatic cancer in the national cancer registry ‐ reconsidering the incidence and survival rates. Eur J Cancer 2017;72:186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parkin DM. The evolution of the population‐based cancer registry. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:603–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bray F, Colombet M, Mery L, et al. Cancer incidence in five continents, vol. XI Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zanetti R, Schmidtmann I, Sacchetto L, et al. Completeness and timeliness: cancer registries could/should improve their performance. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1091–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berkel J. General practitioners and completeness of cancer registry. J Epidemiol Community Health 1990;44:121–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schouten LJ, Hoppener P, van den Brandt PA, et al. Completeness of cancer registration in Limburg, The Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol 1993;22:369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moller H, Richards S, Hanchett N, et al. Completeness of case ascertainment and survival time error in English cancer registries: impact on 1‐year survival estimates. Br J Cancer 2011;105:170–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brewster DH, Stockton DL. Ascertainment of breast cancer by the Scottish cancer registry: an assessment based on comparison with five independent breast cancer trials databases. Breast 2008;17:104–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Larsen IK, Smastuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. Data quality at the cancer registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1218–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leinonen MK, Miettinen J, Heikkinen S, et al. Quality measures of the population‐based Finnish cancer registry indicate sound data quality for solid malignant tumours. Eur J Cancer 2017;77:31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorez M, Bordoni A, Bouchardy C, et al. Evaluation of completeness of case ascertainment in Swiss cancer registration. Joining forces for better cancer registration in Europe. Eur J Cancer Prev 2017;26:S139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paapsi K, Magi M, Mikkel S, et al. The impact of under‐reporting of cases on the estimates of childhood cancer incidence and survival in Estonia. Joining forces for better cancer registration in Europe. Eur J Cancer Prev 2017;26:S147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sigurdardottir LG, Jonasson JG, Stefansdottir S, et al. Data quality at the Icelandic cancer registry: comparability, validity, timeliness and completeness. Acta Oncol 2012;51:880–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Brien K, Comber H, Sharp L. Completeness of case ascertainment at the Irish National Cancer Registry. Ir J Med Sci 2014;183:219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Londero SC, Mathiesen JS, Krogdahl A, et al. Completeness and validity in a national clinical thyroid cancer database: DATHYRCA. Cancer Epidemiol 2014;38:633–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dimitrova N, Parkin DM. Data quality at the Bulgarian National Cancer Registry: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Cancer Epidemiol 2015;39:405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. GACvd S, Coebergh JWW, Schouten LJ, et al. Cancer incidence in The Netherlands in 1989 and 1990: first results of the nationwide Netherlands cancer registry. Eur J Cancer 1995;31:1822–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ikram MA, Brusselle GGO, Murad SD, et al. The Rotterdam study: 2018 update on objectives, design and main results. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:807–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lex A, Gehlenborg N, Strobelt H, et al. UpSet: visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 2014;20:1983–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Working Group Report . International rules for multiple primary cancers (ICD‐0 third edition). Eur J Cancer Prev 2005;14:307–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stotter A, Bright N, Silcocks PB, et al. Effect of improved data collection on breast cancer incidence and survival: reconciliation of a registry with a clinical database. BMJ 2000;321:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qiu M, Qiu H, Jin Y, et al. Pathologic diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the United States: its status and prognostic value. J Cancer 2016;7:694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Rijke JM, Schouten LJ, Schouten HC, et al. Age‐specific differences in the diagnostics and treatment of cancer patients aged 50 years and older in the province of Limburg, The Netherlands. Ann Oncol 1996;7:677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Turner NJ, Haward RA, Mulley GP, et al. Cancer in old age—is it inadequately investigated and treated? BMJ 1999;319:309–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamaker ME, Hamelinck VC, van Munster BC, et al. Nonreferral of nursing home patients with suspected breast cancer. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:464–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bill‐Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;370:932–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schouten LJ, Jager JJ, van den Brandt PA. Quality of cancer registry data: a comparison of data provided by clinicians with those of registration personnel. Br J Cancer 1993;68:974–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained upon request. Requests should be directed toward the management team of the Rotterdam Study (secretariat.epi@erasmusmc.nl), which has a protocol for approving data requests. Because of restrictions based on privacy regulations and informed consent of the participants, data cannot be made freely available in a public repository. The Rotterdam Study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC (registration number MEC 02.1015) and by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (Population Screening Act WBO, license number 1071272‐159521‐PG). The Rotterdam Study has been entered into the Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR; www.trialregister.nl) and into the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp/network/primary/en/) under shared catalogue number NTR6831.