Summary

Background

Both vedolizumab and ustekinumab can be considered for the treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD) when anti‐TNF treatment fails. However, head‐to‐head trials are currently not available or planned.

Aim

To compare vedolizumab and ustekinumab in Crohn´s disease patients in a prospective registry specifically developed for comparative studies with correction for confounders.

Methods

Crohn´s disease patients, who failed anti‐TNF treatment and started vedolizumab or ustekinumab in standard care as second‐line biological, were identified in the observational prospective Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis Registry. Corticosteroid‐free clinical remission (Harvey Bradshaw Index ≤4), biochemical remission (C‐reactive protein ≤5 mg/L and fecal calprotectin ≤250 µg/g), combined corticosteroid‐free clinical and biochemical remission, and safety outcomes were compared after 52 weeks of treatment. To adjust for confounding and selection bias, we used multiple logistic regression and propensity score matching.

Results

In total, 128 vedolizumab‐ and 85 ustekinumab‐treated patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. After adjusting for confounders, ustekinumab‐treated patients were more likely to achieve corticosteroid‐free clinical remission (odds ratio [OR]: 2.58, 95% CI: 1.36‐4.90, P = 0.004), biochemical remission (OR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.10‐4.96, P = 0.027), and combined corticosteroid‐free clinical and biochemical remission (OR: 2.74, 95% CI: 1.23‐6.09, P = 0.014), while safety outcomes (infections: OR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.63‐2.54, P = 0.517; adverse events: OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 0.62‐2.81, P = 0.464; hospitalisations: OR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.32‐1.39, P = 0.282) were comparable between the two groups. The propensity score matched cohort with sensitivity analyses showed comparable results.

Conclusions

Ustekinumab was associated with superior effectiveness outcomes when compared to vedolizumab, while safety outcomes were comparable after 52 weeks of treatment in CD patients who have failed anti‐TNF treatment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic intermittent disease of the gastrointestinal tract with a heterogeneous presentation and treatment response. Anti‐TNF agents are currently considered a first‐line biological treatment after failure of immunosuppressive therapy for moderate to severe disease with cumulative exposure rates exceeding 40% after 5 years of disease duration in population‐based cohorts. 1 , 2 However, up to two‐thirds of CD patients discontinue anti‐TNF‐treatment over time due to primary or secondary nonresponse or adverse effects. 3 , 4 New treatment options with different mechanisms of action, such as vedolizumab and ustekinumab, are currently available for patients who fail anti‐TNF treatment. 5 , 6 Vedolizumab is a monoclonal antibody inhibiting the interaction between the α4β7 integrin and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule‐1 (MAdCAM‐1) resulting in the blocking of lymphocyte homing to the inflamed gut tissue. 5 Ustekinumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting the p40 subunit of interleukin (IL)‐12 and IL‐23 thereby interfering with the IL‐12‐ and IL‐23‐mediated signal transduction. 6 Although both treatment options are effective for induction and maintenance of remission in CD patients, it is unclear how these two biologicals should be positioned after anti‐TNF failure.

The efficacy of vedolizumab and ustekinumab has been studied in randomised placebo controlled trials. Almost half of the patients included in these phase 3 registration trials were anti‐TNF naïve, 5 , 6 while observational cohort studies have shown that 85%‐100% of patients receiving vedolizumab and ustekinumab in daily practice are anti‐TNF exposed. 7 , 8 For CD, therapeutic efficacy of biologicals tends to be substantially lower when patients have failed prior biological treatment. 6 , 9 Furthermore, approximately one‐third of CD patients in standard care are eligible for phase 3 clinical trials, which is mainly due to strict in‐ and exclusion criteria. 10 As a result, data from phase 3 trials cannot easily be extrapolated to daily clinical practice.

The limited external validity of phase 3 trials in addition to the complicated and varying study designs with re‐randomisation of responders after the induction phase, confer reduced value to findings obtained with any indirect comparison of vedolizumab vs ustekinumab by network meta‐analyses. Moreover, no head‐to‐head trials comparing vedolizumab vs ustekinumab in anti‐TNF refractory CD patients are available or planned.

When randomised trials are not available, quasi‐experimental designs in prospective cohorts yield the best available evidence to approximate a causal treatment effect. 11 In this setting, it is important to select patients naïve to the selected therapies with an equal chance to receive either treatment. Second, the same outcomes must be measured at fixed timepoints. Third, both patient cohorts must have a comparable chance to obtain the selected outcome (eg the same disease activity at baseline, comparable phenotype and case‐mix variables). For this purpose, we developed the ‘Initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC) Registry’, designed to compare the effectiveness and safety of different treatments by adopting an uniform follow‐up protocol for all therapies and using statistical techniques in order to limit selection bias and confounding. 11 , 12

The aim of this study was to assess the comparative effectiveness of vedolizumab and ustekinumab in CD patients who failed anti‐TNF treatment in a real‐life setting using multiple logistic regression models with correction for confounders and propensity score matching.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

The ICC Registry was developed to determine the effectiveness, safety and usage of newly registered treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), as previously described. 12 , 13 Briefly, patients who initiated specified therapies in 15 hospitals in the Netherlands were followed for 2 years with a pre‐defined follow‐up schedule of out‐patient visits designed to closely follow regular care. The registered visits are prospectively scheduled at initiation of therapy (baseline) and at week 12, 24, 52 and 104 or until the medication is discontinued. For uniformity and comparative purposes, timepoints and outcomes are identical for all registered treatments. Data collection is carried out using an electronic case report form. In the Netherlands, both vedolizumab and ustekinumab may be prescribed without restrictions before and after anti‐TNF failure in CD patients.

2.2. Participants

Patients ≥16 years of age with an established IBD diagnosis starting vedolizumab or ustekinumab in regular care at the participating centres were eligible for the ICC Registry. There were no exclusion criteria for the Registry. Subsequently, we selected patients for the current study with the following inclusion criteria at baseline: (a) both clinical (Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) >4) and objective disease activity as evidenced by a C‐reactive protein (CRP) concentration >5 mg/L and/or faecal calprotectin level >250 µg/g and/or endoscopic and/or radiologic signs of disease activity (global assessment), (b) prior anti‐TNF failure, (c) no prior exposure to vedolizumab and/or ustekinumab, and (d) a follow‐up duration of at least 52 weeks prior to the analysis. Patients received intravenous (IV) treatment with vedolizumab with an induction regimen of 300 mg at week 0, 2 and 6, according to label. In case of insufficient response, an additional vedolizumab infusion could be administered at week 10, which was done at the discretion of the treating physician. Maintenance treatment consisted of 300 mg vedolizumab infusions every 8 weeks. Ustekinumab treatment was initiated with a weight‐based IV infusion at baseline according to label (260 mg < 55 kg, 390 mg between 55 kg and 85 kg, 520 mg > 85 kg). The first subcutaneous (SC) 90 mg induction dose was administered at week 8 followed by a subsequent maintenance SC dose of 90 mg every 8‐12 weeks. Interval shortening was permitted for both treatments at the discretion of the treating physician.

2.3. Outcomes and definitions

The primary outcome of this study was the proportion of patients in corticosteroid‐free clinical remission (ie HBI ≤4) at week 52. Secondary effectiveness outcomes included: biochemical remission (defined as a CRP serum concentration ≤5 mg/L and a faecal calprotectin level ≤250 µg/g), combined corticosteroid‐free clinical and biochemical remission, vedolizumab and ustekinumab interval shortening, and discontinuation rate. Reason for discontinuation of both treatments was based on the discretion of the treating physician and categorised as follows: lack of initial response, loss of response, adverse events, malignancy, pregnancy or at request of the patient. The reported safety outcomes included the number of medication‐related adverse events, infections and disease‐related hospitalisations per 100 patient years. Adverse events were classified as possibly or probably related. Adverse events requiring discontinuation of treatment were classified separately. Infections were classified as mild (no antibiotics or antiviral medication necessary), moderate (oral antibiotics or antiviral medication required) or severe (hospitalisation and/or IV administrated antibiotics or anti‐viral medication).

Follow‐up time was determined based on the date of the initial IV infusion with vedolizumab or ustekinumab until the last visit used in the analysis. Patients who discontinued treatment were considered treatment failures and were classified as nonresponders in determining the effectiveness outcomes. Only patients who discontinued treatment because of pregnancy were considered censored cases at time points after treatment discontinuation. When patients changed hospital to continue treatment, the information of the subsequent visits would be collected through contact with the respective patient and their new treatment facility. Patients who stopped going to the hospital to receive their infusions or SC injections were recorded as discontinued at request of patient, were considered treatment failures and imputed as nonresponders in the subsequent visits.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Since there was no random assignment to receive either vedolizumab or ustekinumab, two different methods to reduce the effect of treatment‐selection bias and confounders were used to analyse the data. First, we used multiple logistic regression models with correction for confounders. Second, we used propensity scores to create a cohort of matched patients with equal distribution of baseline variables.

The multiple regression analysis to assess the treatment effect on corticosteroid‐free clinical remission at week 52 was corrected for potential confounders a priori agreed upon, and were defined based on an assumed association on either the clinical outcomes or disease severity. The variables included: current smoker, disease duration, complicated disease (stricturing or penetrating behaviour), prior CD‐related surgery, number of prior anti‐TNF treatments, HBI at baseline, and biochemical disease activity at baseline. To further optimise our model we added each baseline variable separately to the regression model. Confounders that had a relevant impact on the association, defined as >10% difference of the odds ratio (OR) for the main independent factor (medicine), were identified. Through this method, corticosteroid use at baseline was found to have a relevant impact on the association. This variable was initially not used for the primary analysis due to the clinicians preference to start corticosteroids in combination with vedolizumab because of the longer induction period and not accurately reflecting severe disease activity at baseline, in contrast with the reason to start concomitant corticosteroids with ustekinumab. We did use corticosteroid use at baseline in our sensitivity analysis. For the safety analysis we used variables associated with infections or adverse events: gender, age, disease duration, concomitant medication, follow‐up duration, and clinical and biochemical disease activity.

For the sensitivity analyses, we created a cohort of vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients with evenly distributed baseline variables through propensity score matching. A propensity score is the conditional probability of receiving either vedolizumab or ustekinumab, given the observed co‐variates. The propensity scores were obtained using a nonparsimonious logistic regression model based on the selected variables. The region of common support was assessed by examining the graph of propensity scores of the treatments. The matching was done on a one‐to‐one, nearest neighbour (calliper: 0.2 of the SD of the logit of the propensity score) basis without replacement. The resulting matched pairs were used in the subsequent analyses to assess the comparative effectiveness.

The confounders for the propensity score matching were also discussed and agreed upon before the data analysis. Given the possibility to adjust for more baseline variables when using propensity score matching when the occurrence of treatment is more common than the outcome, 14 we added variables resulting in: disease duration, location and behaviour, current smoker, prior IBD surgery, number of prior anti‐TNF therapies, HBI at baseline, biochemical disease activity at baseline, corticosteroid and immunosuppressant use at baseline.

All analyses were based on an intention‐to‐treat basis. Descriptive variables were expressed as means with SDs (±) or as medians with an interquartile range (IQR). Differences in baseline characteristics between vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients were assessed using the Mann‐Whitney U test or chi‐squared test. The McNemar test was used for the propensity score matched cohort to compare the paired proportions. 15 Statistical analyses were performed with spss statistics version 24 and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05, based on two‐sided testing.

2.5. Ethical consideration

The study was reviewed and approved by the Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects at the Radboudumc (Institutional Review Board: 4076).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

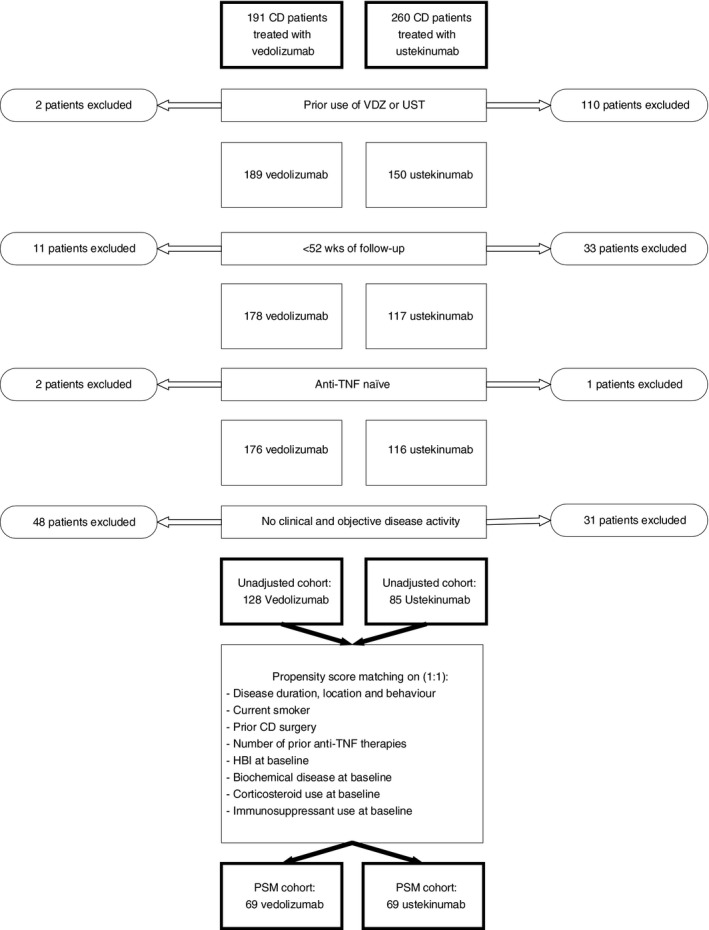

A total of 191 vedolizumab‐ and 260 ustekinumab‐treated CD patients were enrolled in the ICC Registry. We identified 128 vedolizumab‐ and 85 ustekinumab‐treated patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria of our study (Figure1).

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart of Crohn’s disease patients treated with either vedolizumab or ustekinumab who are included in the current study. CD, Crohn’s disease; VDZ, vedolizumab; UST, ustekinumab; anti‐TNF, anti tumour necrosis factor; PSM, propensity score matched

Baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The 128 vedolizumab‐ and 85 ustekinumab‐treated CD patients who failed prior anti‐TNF treatment were followed for 104 (IQR: 104‐104) and 53 (52‐104) weeks, respectively. Differences between vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients were observed in the rate of prior intestinal surgery (vedolizumab: 49.2% vs ustekinumab: 64.7%, P = 0.03), and concomitant medication (immunosuppressants [thiopurines and methotrexate] and corticosteroids) use at baseline (P < 0.01), as outlined in Table 1. All other variables were not significantly different, including clinical and biochemical disease activity parameters.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Crohn’s disease patients initiating vedolizumab or ustekinumab treatment

| Baseline characteristics | Vedolizumab (n = 128) | Ustekinumab (n = 85) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age a , median (IQR) | 36.6 (26.9‐50.8) | 38.7 (28.5‐52.1) | 0.468 |

| Gender—male, N (%) | 44 (34.4) | 34 (40.0) | 0.404 |

| Current smoker, N (%) | 32 (25.0) | 21 (24.7) | 0.961 |

| Disease duration in years, Median (IQR) | 11.0 (6.4‐18.1) | 15.3 (8.4‐21.9) | 0.077 |

| Follow‐up duration in weeks, median (IQR) | 104.0 (104.0‐104.0) | 53.1 (52.0‐104.0) | <0.001 |

| Disease location b , a , N (%) | 0.829 | ||

| Ileum | 39 (30.5) | 29 (34.1) | |

| Colon | 41 (32.0) | 27 (31.8) | |

| Ileocolonic | 48 (37.5) | 29 (34.1) | |

| Upper GI involvement, N (%) | 15 (11.7) | 5 (5.9) | 0.153 |

| Disease behavior b , a , N (%) | 0.131 | ||

| Inflammatory disease | 76 (59.4) | 37 (43.5) | |

| Stricturing disease | 32 (25.0) | 28 (32.9) | |

| Penetrating disease | 19 (14.8) | 18 (21.2) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.8) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Peri‐anal disease b , a , N (%) | 20 (16.3) | 9 (10.6) | 0.256 |

| Prior intestinal resections, N (%) | 65 (49.2) | 55 (64.7) | 0.026 |

| Prior peri‐anal interventions, N (%) | 27 (21.1) | 19 (22.4) | 0.209 |

| Prior anti‐TNF therapy exposure, N (%) | 0.309 | ||

| ≥1 | 128 (100) | 85 (100) | |

| ≥2 | 102 (79.7) | 59 (69.4) | |

| Disease activity—baseline Median (IQR) | 0.985 | ||

| Harvey Bradshaw Index, Median (IQR) | 9 (6‐12) | 10 (5‐12) | |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 8 (4‐21) | 9 (3‐21) | 0.845 |

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g | 881 (359‐1800) | 554 (215‐1528) | 0.227 |

| Concomitant medication a , N (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Corticosteroids | 40 (31.3) | 10 (11.8) | |

| Immunosuppressants | 24 (18.8) | 20 (23.5) | |

| Both corticosteroids and immunosuppressants | 20 (15.6) | 7 (8.2) | |

Abbreviations: anti‐TNF, anti tumour necrosis factor, IQR, interquartile rage; N, number of.

At baseline.

At maximum extent of disease.

To create the sensitivity cohort, we applied propensity scores in order to match patients. The baseline variables used to match included: disease duration, location and behaviour, current smoker, prior IBD‐related surgery, number of prior anti‐TNF therapies, HBI at baseline, biochemical disease activity at baseline, corticosteroid and immunosuppressant use at baseline. This cohort consisted of 69 vedolizumab‐treated and 69 ustekinumab‐treated patients with no significant differences regarding baseline variables (Table 2). The median HBI, CRP and faecal calprotectin in this cohort for vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients was: 8 (IQR: 6‐12) vs 10 (IQR: 7‐12), P = 0.178, 7 (IQR: 3‐19) vs 9 (IQR: 3‐21), P = 0.821, and 661 (IQR: 356‐1504) vs 610 (IQR: 288‐1800), P = 0.853, respectively.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of propensity score matched cohort of Crohn’s disease patients initiating vedolizumab or ustekinumab treatment

| Baseline characteristics | Vedolizumab (n = 69) | Ustekinumab (n = 69) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age b , a , median (IQR) | 36.3 (26.0‐51.4) | 38.4 (27.6‐50.2) | 0.662 |

| Gender—male, N (%) | 24 (34.8) | 23 (33.3) | 0.857 |

| Current smoker, N (%) | 15 (21.7) | 17 (24.6) | 0.687 |

| Disease duration in years, Median (IQR) | 11.0 (6.8‐18.6) | 13.4 (7.3‐23.5) | 0.392 |

| Disease location b , a , N (%) | 0.920 | ||

| Ileum | 21 (30.4) | 23 (33.3) | |

| Colon | 21 (30.4) | 21 (30.4) | |

| Ileocolonic | 27 (39.1) | 25 (36.2) | |

| Upper GI involvement | 6 (8.7) | 4 (5.8) | 0.511 |

| Disease behaviour b , a , N (%) | 0.996 | ||

| Inflammatory disease | 33 (47.8) | 33 (47.8) | |

| Stricturing disease | 20 (29.0) | 21 (30.4) | |

| Penetrating disease | 15 (21.7) | 14 (20.3) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Peri‐anal disease b , a , N (%) | 14 (20.6) | 6 (8.7) | 0.093 |

| Prior intestinal resections, N (%) | 41 (59.4) | 43 (62.3) | 0.727 |

| Prior perianal interventions, N (%) | 18 (26.1) | 11 (15.9) | 0.141 |

| Prior anti‐TNF therapy exposure, N (%) | 0.713 | ||

| ≥1 | 69 (100) | 69 (100) | |

| ≥2 | 47 (68.1) | 49 (71.0) | |

| Disease activity—baseline, Median (IQR) | |||

| Harvey Bradshaw Index | 8 (6‐12) | 10 (7‐12) | 0.178 |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 7 (3‐19) | 9 (3‐21) | 0.821 |

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g | 661 (356‐1504) | 610 (288‐1800) | 0.853 |

| Concomitant medication b , N (%) | 0.505 | ||

| Corticosteroids | 14 (20.3) | 10 (14.5) | |

| Immunosuppressants | 18 (26.1) | 14 (20.3) | |

| Both corticosteroids and immunosuppressants | 4 (5.8) | 7 (10.1) | |

Patients were matched for: disease duration, location and behaviour, current smoker, prior Crohn’s diease surgery, number of prior anti‐TNF therapies, HBI at baseline, biochemical disease activity at baseline, corticosteroid and immunosuppressant use at baseline.

Abbreviations: anti‐TNF, anti tumour necrosis factor, IQR, interquartile rage; HBI, Harvey Bradshaw Index; N, number of.

At baseline.

At maximum extent of disease.

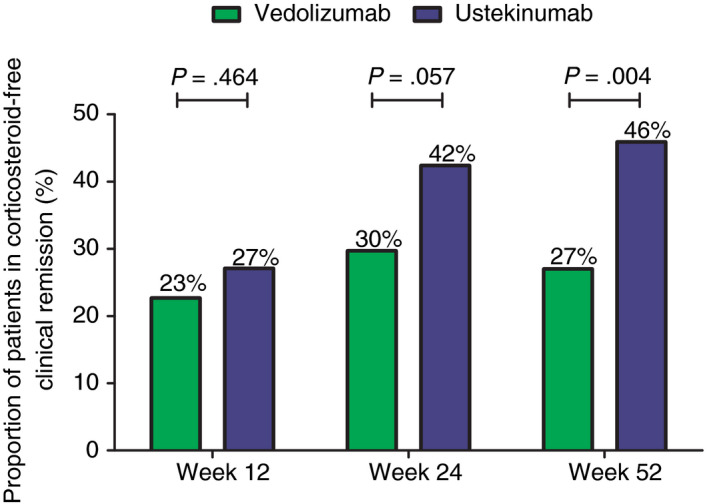

3.2. Corticosteroid‐free clinical remission

Unadjusted corticosteroid‐free clinical remission rates in vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients at week 12, 24 and 52 were: 22.7% (n = 29/128) vs 27.1% (n = 23/85) (P = 0.464), 29.7% (n = 38/128) vs 42.4% (n = 36/85) (P = 0.057), and 26.8% (n = 34/127) vs 45.9% (n = 39/85) (P = 0.004), respectively (Figure 2). The unadjusted OR of achieving corticosteroid‐free clinical remission at week 52 was 2.31 (95% CI: 1.29‐4.14, P = 0.004) when treated with ustekinumab compared to vedolizumab. After using multiple logistic regression, the adjusted OR was 2.58 (95% CI: 1.36‐4.90, P = 0.004) in favour of ustekinumab. When corticosteroid use at baseline was added to this model, the OR changed to 2.31 (95% CI: 1.20‐4.47, P = 0.013). There were no baseline characteristics distinguishing patients who achieved corticosteroid‐free clinical remission with either vedolizumab or ustekinumab.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted proportion of Crohn’s disease patients achieving corticosteroid‐free clinical remission (HBI ≤4). HBI, Harvey Bradshaw Index

Corticosteroid‐free clinical remission rates in the propensity score matched cohort in vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients at week 12, 24, and 52 were: 29.0% vs 20.3% (P = 0.327), 30.4% vs 42.0% (P = 0.215), and 29.0% vs 46.4% (P = 0.043), respectively.

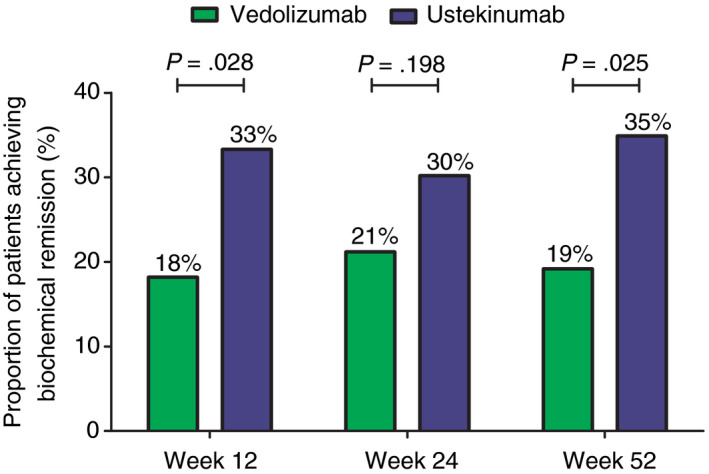

3.3. Biochemical remission

Unadjusted biochemical remission rates in vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients at week 12, 24 and 52 were: 18.2% vs 33.3% (P = 0.028), 21.2% vs 30.2% (P = 0.198), and 19.2% vs 34.9% (P = 0.025), respectively (Figure 3). The OR of achieving biochemical remission at week 52 in the unadjusted analysis was 2.26 (95% CI: 1.10‐4.64, P = 0.027) in favour of ustekinumab. The adjusted OR was 2.34 (95% CI: 1.10‐4.96, P = 0.027) in favour of ustekinumab. When corticosteroid use at baseline was added to this model, the OR changed to 2.66 (95% CI: 1.20‐5.89, P = 0.013).

Figure 3.

Unadjusted proportion of Crohn’s disease patients achieving biochemical remission (CRP ≤5 mg/L and faecal calprotectin ≤250 µg/g). CRP, C‐reactive protein

Biochemical remission rates in the propensity score matched cohort in vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients at week 12, 24 and 52 were: 18.9% vs 40.5% (P = 0.096), 21.6% vs 40.5% (P = 0.210), and 13.2% vs 42.1% (P = 0.013), respectively.

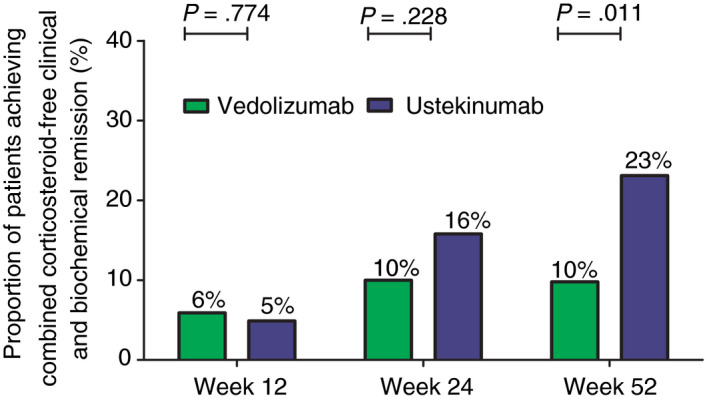

3.4. Combined corticosteroid‐free clinical and biochemical remission

Unadjusted combined corticosteroid‐free clinical and biochemical remission rates in vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients at week 12, 24 and 52 were: 5.9% vs 4.9% (P = 0.774), 10.0% vs 15.8% (P = 0.228), and 9.8% vs 23.1% (P = 0.011), respectively. The OR of achieving combined clinical and biochemical remission after 52 weeks of treatment in the unadjusted analysis was 2.75 (95% CI: 1.24‐6.09, P = 0.013) in favour of ustekinumab. We could not correct for all confounding factors because this combined endpoint was achieved in a limited number of patients, hence we only corrected for HBI at baseline and smoking. When correcting for these variables, the OR was 2.74 (95% CI: 1.23‐6.09, P = 0.014) in favour of ustekinumab.

A significantly higher combined clinical and biochemical remission rate at week 52 was found in vedolizumab‐ vs ustekinumab‐treated patients in the propensity score matched cohort, whereas no significant differences were found at week 12 or week 24 (week 12: vedolizumab: 5.2% vs ustekinumab: 5.2% [P = 1.000], week 24: 7.3% vs 21.8% [P = 0.077], week 52: 10.2% vs 27.1% [P = 0.031], respectively).

3.5. Interval shortening

Of the 128 vedolizumab‐treated patients, 50.8% (n = 65/128) received an extra week 10 infusion. During maintenance therapy, 24.2% (n = 31/128) received interval shortening (to every 6 weeks or less) after a median treatment duration of 30.0 weeks (IQR: 14.0‐46.0). Of these patients, 35.5% (n = 11/31) obtained corticosteroid‐free clinical remission at week 52.

Of the 85 ustekinumab‐treated patients, 51.8% (n = 44/85) received maintenance treatment with SC injections at an 8‐weekly interval (Q8W) or less (one patient Q4W, and one patient Q6W). During follow‐up, 28.2% (n = 24/85) received interval shortening (from Q12W to Q8W or any interval less than Q8W). Of these patients, 62.5% (n = 15/24) achieved corticosteroid‐free clinical remission at week 52.

In the propensity score matched cohort, 44.9% (n = 31/69) of vedolizumab‐treated patients received an additional week 10 infusion and 27.5% (n = 19/69) received interval shortening during follow‐up. Of the ustekinumab‐treated patients, 55.1% (n = 38/69) received maintenance treatment with SC injections at an Q8W interval or less (one patient Q4W) and 29.0% (n = 20/69) received interval shortening after the first SC injection.

3.6. Safety

The 128 vedolizumab‐ and 85 ustekinumab‐treated patients received treatment for a total of 140.9 and 85.0 patient‐years, respectively (Table 3). During follow‐up, the number of adverse events requiring treatment discontinuation, severe infections and hospitalisations for vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated patients was: 7 (5.0 per 100 patient years) vs 2 (2.4 per 100 patient years), 3 (2.1 per 100 patient years) vs 5 (5.9 per 100 patient years), and 36 (25.6 per 100 patient years) vs 17 (20.0 per 100 patient years), respectively (Table 3). The total number of all adverse events (possibly‐ and probably‐related and reasons for treatment discontinuation) and infections (mild, moderate and severe) was: 40 (28.4 per 100 patient years) vs 32 (37.7 per 100 patient years) and 52 (36.9 per 100 patient years) vs 39 (45.9 per 100 patient years), respectively. When corrected for gender, age, disease duration, concomitant medication (immunomodulators and corticosteroids) use, follow‐up duration, and clinical and biochemical disease activity, there were no significant differences in infection rate (OR: 1.26, 95%CI: 0.63‐2.54, P = 0.517), adverse events (OR: 1.33, 95%CI: 0.62‐2.81, P = 0.464) or hospitalisations (OR: 0.67, 95%CI: 0.32‐1.39, P = 0.282) between vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab treated patients.

Table 3.

Adverse events

| Vedolizumab: 140.86 y | Ustekinumab: 84.99 y | |

|---|---|---|

| Possibly related | 27 (19.2 per 100 patient y) | 27 (31.8 per 100 patient y) |

| Cutaneous lesions | 7 | 7 |

| Infusion related | 6 | — |

| Arthralgia | 4 | 3 |

| Gastrointestinal | — | 4 |

| Respiratory | 1 | 1 |

| Fatigue | 1 | — |

| Headache | 2 | 8 |

| Cardiac event | 1 | — |

| Itch | 1 | — |

| Psychiatric | 1 | — |

| Vascular | — | 2 |

| Muscle strain | — | 1 |

| Severe hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia | — | 1 |

| Vertigo | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | — |

| Probably related | 6 (4.3 per 100 patient y) | 3 (3.5 per 100 patient y) |

| Infusion related | 4 | — |

| Cutaneous lesions | 1 | 2 |

| Headache | — | 1 |

| Dizziness | 1 | |

| Adverse event requiring discontinuation | 7 (5.0 per 100 patient y) | 2 (2.4 per 100 patient y) |

| Infusion related | 2 | — |

| Arthralgia | 3 | 1 |

| Nervous system | 1 | — |

| Recurrent infections | 1 | 1 |

| Mild infections | 30 (21.3 per 100 patient y) | 19 (22.4 per 100 patient y) |

| Upper respiratory | 12 | 6 |

| Flu‐like syndrome | 6 | 5 |

| Gastrointestinal | 5 | 3 |

| Fever (no focus) | 3 | — |

| Cutaneous lesions | 1 | — |

| Herpes zoster | 1 | — |

| Soft tissue | 1 | 3 |

| Cold sore | 1 | 2 |

| Moderate infections | 19 (13.5 per 100 patient y) | 15 (17.6 per 100 patient y) |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 | — |

| Upper respiratory | 6 | 3 |

| Other | 1 | — |

| Urinary tract | 2 | 4 |

| Cutaneous lesions | 1 | 2 |

| Herpes zoster | 1 | — |

| Pneumonia | — | 5 |

| Fever (no focus) | 1 | — |

| Jaw/teeth | 1 | — |

| Soft tissue | — | 1 |

| Severe infections | 3 (2.1 per 100 patient y) | 5 (5.9 per 100 patient y) |

| Gastrointestinal | — | 3 |

| Pneumonia | 2 | — |

| Upper respiratory | 1 | — |

| Central catheter | — | 2 |

| Hospitalisation | 36 (25.6 per 100 patient y) | 17 (20.0 per 100 patient y) |

Number and details of adverse events during treatment of Crohn’s disease patients with vedolizumab or ustekinumab. Infections were classified as: mild infections: no antibiotics or antiviral medication; moderate infections: oral antibiotics or antiviral medication; severe infections: hospitalisation or intravenously administrated antibiotics or antiviral medication.

No significant differences were found in the propensity score matched cohort when corrected for follow‐up duration regarding infection rate (OR: 1.13, 95%CI: 0.53‐2.42, P = 0.758), adverse events (OR: 1.32 95% CI 0.52‐3.36, P = 0.556) and hospitalisations (OR: 0.42 95% CI: 0.17‐1.01, P = 0.052).

3.7. Treatment discontinuation

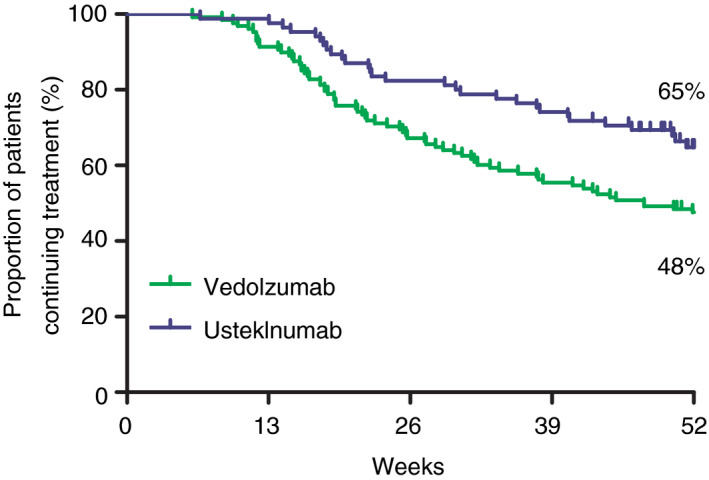

For comparative purposes, only patients discontinuing treatment within 52 weeks of treatment are reported in this paragraph. Treatment discontinuation was observed in 52.3% (n = 67/128) and 34.1% (n = 29/85) of patients in the vedolizumab and ustekinumab cohorts after a median follow‐up duration of 21.6 (IQR: 15.9‐32.1) and 23.7 (IQR: 18.1‐39.1) weeks, respectively (Table 4). The main reason for discontinuation of both treatments was lack of response (vedolizumab: 76.5%, ustekinumab: 86.2%). In the unadjusted analysis, CD patients receiving treatment with ustekinumab had an odds ratio of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.26‐0.81, P = 0.007) to discontinue treatment within 52 weeks when compared to vedolizumab‐treated patients. After correcting for confounders, the adjusted OR was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.25‐0.82, P = 0.009; Figure 4).

Table 4.

Discontinuation within 52 wk of treatment

| Vedolizumab, N = 67 (52.3%) | Ustekinumab, N = 29 (34.1%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration—weeks Median (IQR) | 21.6 (15.9‐32.1) | 23.7 (18.1‐39.1) |

| Reason discontinuation, N (%) | ||

| No response | 52 (76.5) | 25 (86.2) |

| Loss of response | 3 (4.5) | — |

| Adverse events | 4 (6.0) | 2 (6.9) |

| Malignancy | 1 (1.5) | — |

| Pregnancy | 2 (3.0) | — |

| Request patient | 4 (5.9) | 2 (6.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.5) | — |

Reasons for discontinuation vedolizumab‐ or ustekinumab‐treatment in Crohn’s disease patients.

Figure 4.

Unadjusted proportion of Crohn’s disease patients achieving combined corticosteroid‐free clinical and biochemical remission (HBI ≤4, CRP ≤5 mg/L and faecal calprotectin ≤250 µg/g). CRP, C‐reactive protein; HBI, Harvey Bradshaw Index

In the propensity score matched cohort, treatment discontinuation before week 52 occurred in 50.7% vs 29.0% in patients receiving vedolizumab or ustekinumab treatment, respectively (P = 0.009).

4. DISCUSSION

In this nationwide, prospective, comparative effectiveness study, we compared treatment outcomes between vedolizumab and ustekinumab in CD patients with prior failure of anti‐TNF treatment. To this end, we used a registry specifically designed for comparative studies with multiple logistic regression and propensity score matching to adjust for confounding and selection bias. We observed that ustekinumab was associated with superior effectiveness outcomes when compared to vedolizumab for achieving corticosteroid‐free clinical remission (OR: 2.58, 95% CI: 1.36‐4.90, P = 0.004), biochemical remission (OR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.10‐4.96, P = 0.027), the combination of corticosteroid‐free clinical and biochemical remission (OR: 2.74, 95% CI: 1.23‐6.09, P = 0.014), and discontinuation rate (OR: 0.45, 95% CI: 0.25‐0.82, P = 0.009) after 52 weeks (Figure 5) of treatment. The safety outcomes were comparable for both treatments.

Figure 5.

Unadjusted cumulative drug survival of vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated Crohn’s disease patients

The corticosteroid‐free clinical remission rate of vedolizumab (27%)‐ and ustekinumab (46%)‐treated CD patients who failed anti‐TNF in our study is comparable to other real‐life cohorts. Similar to our study, a single‐arm prospective study of vedolizumab‐treated CD patients conducted in the Netherlands and Belgium as well as other observational cohorts showed pooled corticosteroid‐free clinical remission rates of 31% and 32% at 52 weeks, respectively. 7 , 16 To compare the corticosteroid‐free clinical remission rate of ustekinumab‐treated patients is more challenging since there are only two other large reported cohorts (from Belgium and Spain) that followed the registered induction regimen. These two cohorts are characterised by a therapy‐refractory patient population with not only a high percentage of failure of one or more anti‐TNF agents, but also failure of anti‐integrin therapy (68% and 29%, respectively). Compared to our study, the clinical remission rate was lower in the Belgium cohort (week 52: 26%), but higher in the Spanish cohort (week 14: 58%, this cohort week 12: 27%). 17 , 18 When our results are compared to other ustekinumab CD cohorts with different induction regimens, but without prior failure to anti‐integrin therapy, comparable results are found (39% pooled clinical remission rate at week 24 compared to 42% in our study). 8

Both vedolizumab and ustekinumab displayed reassuring safety results. The incidence rate of severe infections, adverse events requiring treatment discontinuation and hospitalisations was relatively low and in line with phase 3 trials and observational studies. 8 , 19 Importantly, when corrected for safety‐related confounders, no significant differences were found between the two treatment groups in terms of safety outcomes.

There are currently no studies available that directly compared vedolizumab‐ and ustekinumab‐treated CD patients. A few studies have indirectly compared these treatments by network meta‐analysis. These studies did not find differences in efficacy or safety outcomes between CD patients receiving vedolizumab or ustekinumab as a second‐line biological in the registration trials. 20 , 21 However, the results of these studies are difficult to interpret, since only responders to induction therapy were enrolled in the maintenance studies supplemented with responders from the open‐label cohorts of which no outcomes are presented. The differences in induction phases and outcomes among the available trials do not allow for a conclusive comparative intention‐to‐treat analysis. A substantial number of cohort studies reported outcomes of CD patients receiving either vedolizumab or ustekinumab but have not compared both treatments. The results of these studies are difficult to compare due to differences in patient populations, methodology and statistical analysis (eg no intention‐to‐treat analysis, Kaplan‐Meier or cox regression survival cohorts).

The positioning of biologicals in IBD patients is an ongoing process and will likely become even more challenging in the nearby future with the arrival of new therapies with additional modes of action. Therefore, strategy and head‐to‐head trials are needed to determine the treatment algorithm beyond the first biological. The VARSITY (comparing vedolizumab vs adalimumab for ulcerative colitis) 22 and SEAVUE (comparing ustekinumab vs adalimumab for CD, NCT03464136) trials represent the first randomised head‐to‐head trials of biologicals in IBD. These studies are an important milestone in IBD research since instead of a placebo, an active comparator is given. Unfortunately, these studies are not primarily focused on patients who have failed anti‐TNF treatment despite the current positioning of vedolizumab and ustekinumab after anti‐TNF failure in CD as shown by observational cohorts. 7 , 8 Our results may aid to the clinical decision‐making process for CD patients after failing anti‐TNF therapy. However, head‐to‐head studies beyond failure of a first biological are needed to guide further treatment in daily practice.

Several strengths of this study allowed us to reliably assess effectiveness outcomes between vedolizumab and ustekinumab after anti‐TNF failure in a large CD cohort in a real‐life setting. All patient visits were scheduled at the same time points using pre‐defined clinical and biochemical outcome measures. Effectiveness and safety outcomes were assessed independently of exclusion criteria of clinical trials and without excluding nonresponders of the induction phase. Furthermore, by selecting patients who are naïve to the designated therapies and by using a follow‐up period of 52 weeks, that is sufficient to reliably assess clinical response, the design did not favour one of the treatment options. A limitation is that we did not use a randomised study design. Hence, it is possible that unknown confounders influenced the results. However, in our analyses we adjusted for important factors widely recognised for being associated with disease severity or a refractory phenotype in CD. Furthermore, there are currently no randomised head‐to‐head trials ongoing or being planned that only include anti‐TNF refractory CD patients. Until these trials will become available, well‐designed observational studies, despite their inherent risk of persisting bias, yield the best available evidence to guide clinical decision making in CD patients following anti‐TNF failure and allows for reproducibility in other cohorts. Dose optimisation was allowed during this study and was used frequently by clinicians for both treatments (vedolizumab week 10: 51%, optimisation: 24%, ustekinumab initiating maintenance treatment Q8W: 52%, optimisation: 28%). Although the impact of dose intensification could not be assessed in this study, it is a reflection of standard care as also shown by other studies (vedolizumab week 10: 64%, optimisation: 59%, ustekinumab Q8W: 71‐100%). 16 , 17 , 23 , 24 Unfortunately, trough levels were not systematically assessed in our study and therefore clinical outcomes could not be correlated with drug levels. Regarding endoscopic assessment, our study design followed regular care. Consequently, endoscopic assessments were performed at the discretion of the treating physician and were therefore not routinely performed at predefined time points. In case endoscopies were available, the main indication was suspected disease activity. As a result, selection bias would be present when reporting this data. A proportion of patients enrolled in the ICC Registry could not be included for this study, mostly due to prior exposure to anti‐integrin or anti‐interleukin treatment. This strategy allowed us to reduce the impact of prior failure to multiple classes of biologicals since the latter is associated with a reduced likelihood of response to the next biological. The objective of our study was to evaluate subsequent therapy after anti‐TNF failure and we therefore believe that although this limitation is present, it does not reduce the external validity of our results for this specific research aim.

In conclusion, this study showed superior effectiveness outcomes associated with ustekinumab compared to vedolizumab in CD patients with prior failure to anti‐TNF treatment, while safety outcomes were comparable. Head‐to‐head studies in CD patients with prior failure to anti‐TNF treatment are needed to confirm these observations. Meanwhile, our results may help guiding clinical decision making after anti‐TNF failure in CD.

AUTHORSHIP

Guarantor of the article: Marieke J. Pierik.

Author contributions: No additional writing assistance was used for this manuscript. VB, CW, GD, AM, ML, NB, BO, FH, MP contributed to the design of the study. All authors collected data, VB, FH and MP analysed the data. VB, FH and MP drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Bjorn Winkens for his assistance in the statistical analyses.

Declaration of personal interests: V.B.C. Biemans has no conflicts of interest to declare. C.J. van der Woude has served on advisory boards and/or received financial compensation from the following companies: MSD, FALK Benelux, Abbott laboratories, Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Takeda, and Ferring during the last 3 years. A.E. van der Meulen‐de Jong has served on advisory boards, or as speaker or consultant for Takeda, Tramedico, AbbVie, and has received grants from Takeda. G. Dijkstra unrestricted research grants from Abbvie, Takeda and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Advisory boards for Mundipharma and Pharmacosmos. Received speakers fees from Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. M. Löwenberg has served as speaker and/or principal investigator for: Abbvie, Celgene, Covidien, Dr. Falk, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen‐Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Protagonist therapeutics, Receptos, Takeda, Tillotts, Tramedico. He has received research grants from AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Achmea healthcare and ZonMW. N.K.H. de Boer has served as a speaker for AbbVie, Takeda and MSD. He has served as consultant and principal investigator for Takeda and TEVA Pharma B.V. He has received (unrestricted) research grants from Dr. Falk and Takeda. B. Oldenburg speaker: Ferring, MSD, Abbvie. Advisory boards: Ferring, MSD, Abbvie, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen. Research Grants: Abbvie, Ferring, Takeda, Pfizer, MSD, dr. Falk. N. Srivastava has no conflict of interest to declare. J.M. Jansen has served on advisory boards, or as speaker or consultant for Abbvie, Amgen, Ferring, Fresenius, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda. A.G.L. Bodelier has served as speaker and/ or participant in advisory board for: Abbvie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Takeda, Vifor Pharma, Mundipharma. R.L. West has participated in advisory board and/or received financial compensation from the following companies: Jansen and Abbvie. A.C. de Vries has participated in advisory board and/or received financial compensation from the following companies: Jansen, Takeda, Abbvie and Tramedico. D.J. de Jong Received consulting fees from Synthon, Pharma, Abbvie, and MSD, and travel fees from Falk Pharma, Takeda, Abbvie, MSD, Ferring, Vifor Pharma, and Cablon Medical. J.J.L. Haans reports personal fees from advisory board for Takeda Nederland B.V., personal fees from advisory board for Lamepro B.V., outside the submitted work. F. Hoentjen has served on advisory boards, or as speaker or consultant for Abbvie, Celgene, Janssen‐Cilag, MSD, Takeda, Celltrion, Teva, Sandoz and Dr Falk , and has received unrestricted grants from Dr Falk, Janssen‐Cilag, Abbvie. M.J. Pierik has served on advisory boards, or as speaker or consultant for Abbvie, Janssen‐Cilag, MSD, Takeda, Ferring, Dr Falk, and Sandoz and has received unrestricted grants from, Janssen‐Cilag, Abbvie and Takeda outside the submitted work.

Appendix 1. The authors’ complete affiliation list

Vince B. C. Biemans, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands; C. Janneke van der Woude, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Gerard Dijkstra, University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; Andrea E. van der Meulen‐de Jong, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands; Mark Löwenberg, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Nanne K. de Boer, Amsterdam University Medical Centre, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam Gastroenterology & Metabolism Research Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Bas Oldenburg, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Nidhi Srivastava, Haaglanden Medisch Centre, the Hague, the Netherlands; Jeroen M. Jansen, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Alexander G. L. Bodelier, Amphia Hospital, Breda, the Netherlands; Rachel L. West, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Annemarie C. de Vries, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Jeoffrey J. L. Haans, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands; Dirk de Jong, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; Frank Hoentjen, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; Marieke J. Pierik, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Biemans VBC, van der Woude CJ, Dijkstra G, et al. Ustekinumab is associated with superior effectiveness outcomes compared to vedolizumab in Crohn’s disease patients with prior failure to anti‐TNF treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:123–134. 10.1111/apt.15745

Frank Hoentjen and Marieke J. Pierik shared authorship.

The authors’ complete list of affiliation are listed in Appendix 1.

The Handling Editor for this article was Professor Roy Pounder, and it was accepted for publication after full peer‐review.

Funding information

No funding has been received for this specific study. Data have been generated as part of routine work of the participating organisations.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jeuring SFG, van den Heuvel TRA, Liu LYL, et al. Improvements in the long‐term outcome of Crohn's disease over the past two decades and the relation to changes in medical management: Results from the population‐based IBDSL cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burisch J, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L for the Epi‐IBD group , et al. Natural disease course of Crohn's disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population‐based inception cohort: an Epi‐IBD study. Gut. 2019;68:423‐433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gisbert JP, Panes J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:760–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Billioud V, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin‐Biroulet L. Loss of response and need for adalimumab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:674–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engel T, Ungar B, Yung DE, et al. Vedolizumab in IBD‐lessons from real‐world experience; a systematic review and pooled analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Engel T, Yung DE, Ma C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of Ustekinumab for Crohn's disease: systematic review and pooled analysis of real‐world evidence. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1232–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease in patients naive to or who have failed tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ha C, Ullman TA, Siegel CA, et al. Patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials do not represent the inflammatory bowel disease patient population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1002–1007; quiz e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brian L, Strom SEK, Hennessy S. Pharmacoepidemiology, 5th edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley‐Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biemans VBC, van der Meulen ‐ de Jong AE, van der Woude CJ, et al. Ustekinumab for Crohn's disease: results of the ICC Registry, a nationwide prospective observational cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(1):33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biemans VBC, van der Woude CJ, Dijkstra G, et al. Vedolizumab for inflammatory bowel disease: Two‐year results of the initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC) Registry, A Nationwide Prospective Observational Cohort Study: ICC Registry ‐ Vedolizumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;107:1189–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin PC. Comparing paired vs non‐paired statistical methods of analyses when making inferences about absolute risk reductions in propensity‐score matched samples. Stat Med. 2011;30:1292–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Löwenberg M, Vermeire S, Mostafavi N, et al. Vedolizumab Induces endoscopic and histologic remission in patients with Crohn's DIsease. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(4):997–1006.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liefferinckx C, Verstockt B, Gils A, et al. Long‐term clinical effectiveness of ustekinumab in patients with Crohn's disease who failed biological therapies: a national cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1401‐1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iborra M, Beltrán B, Fernández‐Clotet A, et al. Real‐world short‐term effectiveness of ustekinumab in 305 patients with Crohn's disease: results from the ENEIDA registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. IM‐UNITI: 3 year efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of ustekinumab treatment of Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;14:23‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pagnini C, Siakavellas SI, Bamias G. Systematic review with network meta‐analysis: efficacy of induction therapy with a second biological agent in anti‐TNF‐experienced Crohn's disease patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:6317057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawalec P, Mocko P. An indirect comparison of ustekinumab and vedolizumab in the therapy of TNF‐failure Crohn's disease patients. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7:101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sands BE, Peyrin‐Biroulet L, Loftus EV, et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate‐to‐severe ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amiot A, Serrero M, Peyrin‐Biroulet L, et al. Three‐year effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multi‐centre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:40–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eberl A, Hallinen T, Af Bjorkesten CG, et al. Ustekinumab for Crohn's disease: a nationwide real‐life cohort study from Finland (FINUSTE). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]