Summary

Background

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) exhibit aberrant activation of the hedgehog pathway. Sonidegib is a hedgehog pathway inhibitor approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCC (laBCC) and metastatic BCC (mBCC) based on primary results of the BOLT study [Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 (sonidegib) Treatment].

Objectives

This is the final 42‐month analysis of the BOLT study, evaluating the efficacy and safety of sonidegib.

Methods

Adults with no prior hedgehog pathway inhibitor therapy were randomized in a 1 : 2 ratio to sonidegib 200 mg or 800 mg once daily. Treatment continued for up to 42 months or until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, death, study termination or withdrawal of consent. The primary efficacy end point was the objective response rate (ORR) by central review, assessed at baseline; weeks 5, 9 and 17; then subsequently every 8 or 12 weeks during years 1 or 2, respectively. Safety end points included adverse event monitoring and reporting.

Results

The study enrolled 230 patients, 79 and 151 in the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively, of whom 8% and 3.3% remained on treatment by the 42‐month cutoff, respectively. The ORRs by central review were 56% [95% confidence interval (CI) 43–68] for laBCC and 8% (95% CI 0·2–36) for mBCC in the 200‐mg group and 46·1% (95% CI 37·2–55·1) for laBCC and 17% (95% CI 5–39) for mBCC in the 800‐mg group. No new safety concerns emerged.

Conclusions

Sonidegib demonstrated sustained efficacy and a manageable safety profile. The final BOLT results support sonidegib as a viable treatment option for laBCC and mBCC.

What's already known about this topic?

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is usually treatable with surgery or radiation therapy, but there are limited treatment options for patients with advanced BCC.

Sonidegib, a hedgehog pathway inhibitor approved for the treatment of advanced BCC, demonstrated clinically relevant efficacy and manageable safety in prior analyses of the phase II randomized, double‐blind BOLT study [Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 (sonidegib) Treatment].

What does this study add?

This final 42‐month analysis of BOLT is the longest follow‐up available for a hedgehog pathway inhibitor.

Clinically relevant efficacy results were sustained from prior analyses, with objective response rates by central review of the approved 200‐mg daily dose of 56% in locally advanced BCC and 8% in metastatic BCC.

No new safety concerns were raised.

The results confirmed sonidegib as a viable long‐term treatment option for patients with advanced BCC.

Short abstract

Linked Comment: Fife. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182:1322–1323.

The incidence of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is increasing worldwide by approximately 1% annually.1, 2 For nonadvanced BCC, primary treatment options include surgical excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, cryotherapy and radiation therapy.3 In a subset of cases, BCCs can become excessively invasive or destructive; these are known as advanced BCCs and are defined as BCCs in which current treatment modalities are contraindicated, potentially because of clinical or patient‐driven factors.4, 5 Complex cases of BCC include locally advanced BCC (laBCC)—in which significant tissue invasion of the tumour can result in considerable deformity and surgical excision is unacceptable—and metastatic BCC (mBCC), whose prognosis is poor, with high morbidity and mortality.5 Inhibition of the hedgehog signalling pathway is among the few treatment options available for patients with advanced BCC.

The hedgehog pathway is a key regulator of cell growth and differentiation during embryonic development but is mostly silenced in adults, with only limited activity in some processes, including hair growth and maintenance of taste.6, 7, 8 BCCs have been found to carry mutations resulting in aberrant activation of hedgehog signalling, primarily in the human homologue of Drosophila patched (PTCH1).6, 9, 10, 11 Mutations in the human homologues of smoothened (SMO) and suppressor of fused (SUFU) have also been found.9, 10, 11

Sonidegib (Odomzo®; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; Cranbury, NJ, U.S.A.) is a hedgehog pathway inhibitor (HPI) selectively targeting smoothened, which is approved in the U.S.A., European Union, Switzerland and Australia for the treatment of adult patients with laBCC that has recurred following surgery or radiation therapy, or those who are not candidates for surgery or radiation therapy.12, 13, 14, 15 In Switzerland and Australia, sonidegib is also approved for the treatment of mBCC.14, 15

A phase I dose escalation study of sonidegib in 103 patients with advanced solid tumours, including 16 with BCC, found 800 mg to be the maximum tolerated once‐daily dose.16 The median times to reach maximum plasma concentration after administration were 2 h and 4 h for patients receiving 200 mg and 800 mg once daily, respectively. Plasma exposure after single‐dose administration increased proportionally with doses ≤ 400 mg once daily and less than proportionally for doses > 400 mg once daily.16

Approval of sonidegib was based on results of the pivotal phase II BOLT trial [Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 (sonidegib) Treatment; NCT01327053], which examined the efficacy and safety of sonidegib in patients with laBCC and mBCC.17, 18 At the 6‐month analysis, treatment with sonidegib 200 mg daily demonstrated objective response rates (ORRs) by central review of 43% in patients with laBCC and 15% in patients with mBCC.17 Subsequent analyses at 12, 18 and 30 months demonstrated sustained efficacy, with ORRs by central review of 56–58% in laBCC and 8% in mBCC.19, 20 Here we report results from the final 42‐month analysis of the BOLT study, representing the longest follow‐up data available from a clinical trial evaluating an HPI.

Patients and methods

Study design

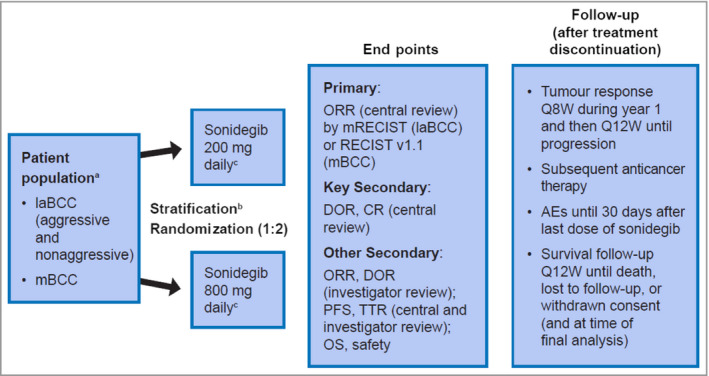

This was a randomized, double‐blind, adaptive phase II clinical study conducted in 58 centres across 12 countries, whose design has been previously reported in detail17 and is summarized in Figure 1. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and an independent ethics committee or institutional review board for each centre approved the study protocol and all amendments. All patients provided informed consent before undergoing any study‐specific procedures.

Figure 1.

Design of the BOLT study – Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 (sonidegib) Treatment. aPatients previously treated with sonidegib or other hedgehog pathway inhibitors were excluded. bStratification was based on stage, disease histology for patients with laBCC (nonaggressive vs. aggressive) and geographical region. cTreatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, death, study termination or withdrawal of consent. AE, adverse event; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CR, complete response; DOR, duration of response; laBCC, locally advanced BCC; mBCC, metastatic BCC; mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; Q8W, every 8 weeks; Q12W, every 12 weeks; TTR, time to tumour response.

Patients age 18 years or older were eligible to enrol if they had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of laBCC not amenable to radiation therapy, curative surgery or other local therapies, or a histologically confirmed diagnosis of mBCC. A World Health Organization performance status ≤ 2 was required for enrolment. Exclusion criteria included major surgery within 4 weeks of initiation of study medication, previous treatment with systemic sonidegib or other HPIs, or other antineoplastic therapy concurrently or within 4 weeks of starting study treatment. Any toxicity from prior therapy could not exceed grade 1.

Enrolled patients were randomized in a 1 : 2 ratio to receive sonidegib 200 mg or 800 mg once daily, approximately 2 h after a light breakfast and without any food intake for 1 h after study drug administration. Randomization was stratified according to disease stage (laBCC or mBCC), histological subtype (aggressive or nonaggressive) for patients with laBCC, and geographical region. BCCs with mixed histological features were assigned a subtype according to their most aggressive component. Patients continued to receive study treatment until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, death, study termination or withdrawal of consent.

Patients, investigators and site staff were masked to dose allocations from randomization until the primary analysis. Masking was maintained through identical packaging, labelling, appearance, odour and dosing schedules for both doses of sonidegib.

Assessments

The primary end point was the ORR by central review, evaluated using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1·1 for patients with mBCC and modified RECIST (mRECIST) for patients with laBCC. Standard RECIST criteria are inadequate for evaluation of laBCC tumour response, especially in the event of post‐treatment morphological changes, such as ulceration, cyst formation, and scarification or fibrosis formation. Thus mRECIST was developed to capture laBCC tumour response adequately using magnetic resonance imaging, colour photography and histology of multiple biopsy samples.17 For patients with mBCC, evaluation was performed using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans, as well as colour clinical photography where appropriate. Tumour assessments were performed at baseline (≤ 21 days prior to start of study treatment); at weeks 5, 9 and 17; then subsequently every 8 weeks during the first year and every 12 weeks during the second year (± 3 days for all postbaseline visits).

Key secondary efficacy end points were complete response rate and duration of response (DOR) per central review. Other secondary efficacy end points included ORR and DOR per local investigator review, progression‐free survival and time to tumour response per central and investigator review, and overall survival.

Key safety assessments included adverse events (AEs), which were monitored throughout the study, reported using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 19·0, and graded for toxicity using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4·03. Additional safety assessments included regular monitoring of haematology, serum chemistry and electrocardiograms, and routine monitoring of vital signs and physical condition. Creatine kinase (CK) was measured prior to starting treatment or within 72 h of the first dose, as well as every week during the first 2 months, and every 4 weeks thereafter while on study treatment.

Statistical analyses

The intent‐to‐treat population included all randomized patients and was used for all efficacy assessments. The safety population included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug and was used for all safety assessments.

Point estimates and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for ORRs and complete response rate. An observed ORR by central review of 30% or higher in either study arm was required for the study to meet its primary end point, and a lower 95% CI limit of 20% or higher was considered clinically meaningful. DOR, progression‐free survival and overall survival were estimated using Kaplan–Meier methodology. Progression‐free survival and overall survival (where estimable) also were summarized using the median and 95% CI. Time to tumour response was summarized using mean, median and SD. Disease control rate (DCR) was calculated as the sum of complete response, partial response and stable disease rates.

Results

Patient disposition, demographics and baseline characteristics

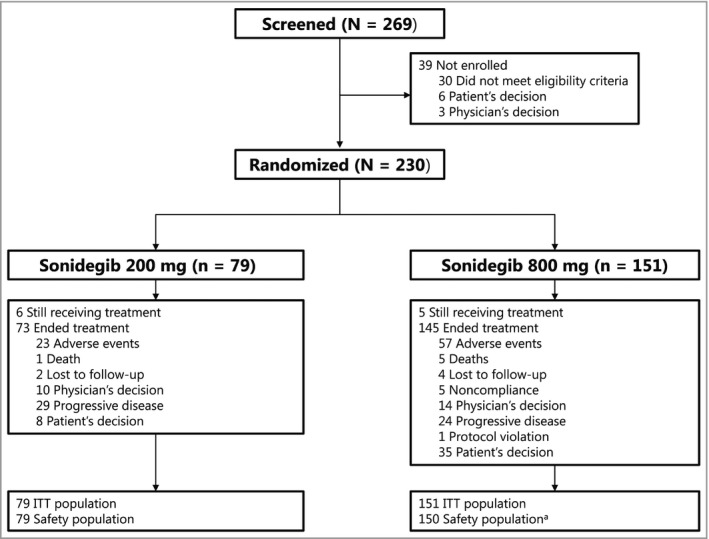

The study enrolled 230 patients, with 79 randomized to sonidegib 200 mg and 151 randomized to sonidegib 800 mg. The intent‐to‐treat population included 194 patients with laBCC (66 receiving 200 mg, 128 receiving 800 mg) and 36 with mBCC (13 receiving 200 mg, 23 receiving 800 mg). At the time of study completion, 11 patients (4·8%) remained on study treatment: six (8%) and five (3·3%) in the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively (Fig. 2). The most common reasons for discontinuation were AEs, seen in 23 (29%) and 57 (37·7%) patients, and progressive disease, seen in 29 (37%) and 24 (15·9%) patients in the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively. Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics were as previously summarized.17 Briefly, the median ages were 67 and 65 years for the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively; patients were predominantly male (61% and 63·6% for the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively); and patients mostly had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance statuses of 0 (63% and 62·9% in the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively) (Table S1; see Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. aOne patient randomized to sonidegib 800 mg did not receive treatment. ITT, intent to treat.

Efficacy outcomes per central review

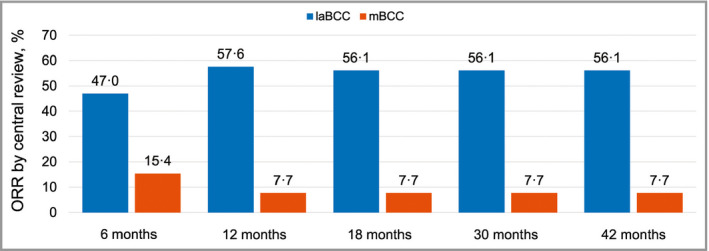

The study continued to meet its primary end point, and the previously observed clinically relevant ORRs per central review for both the 200‐mg and 800‐mg treatment arms were sustained at 42 months (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The ORRs per central review for laBCC and mBCC combined were 48% (95% CI 37–60) and 41·7% (95% CI 33·8–50·0) for the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively. Higher ORRs (95% CI) were observed for patients with laBCC [56% (43–68) and 46·1% (37·2–55·1) for the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively] than for patients with mBCC [8% (0·2–36) and 17% (5–39) for the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively].

Table 1.

Efficacy outcomes per central review at 42 months

| laBCC | mBCC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 mg (n = 66) | 800 mg (n = 128) | 200 mg (n = 13) | 800 mg (n = 23) | |

| ORR, % (95% CI) | 56 (43–68) | 46·1 (37·2–55·1) | 8 (0·2–36) | 17 (5–39) |

| CR, % (95%, CI) | 5 (0·9–13) | 1·6 (0·2–5·5) | 0 (0–25) | 0 (0–15) |

| DCR, % | 91 | 82·0 | 92 | 91 |

| DOR, median, months (95% CI) | 26·1 (NE) | 23·3 (12·2–29·6) | 24·0 (NE) | NE (NE) |

| PFS, median, months (95% CI) | 22·1 (NE) | 24·9 (19·2–33·4) | 13·1 (5·6–33·1) | 11·1 (7·3–16·6) |

| TTR, median, months (95% CI) | 4·0 (3·8–5·6) | 3·8 (3·7–5·5) | 9·2 (NE) | 1·0 (1·0–2·1) |

The results are for the intent‐to‐treat population. BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; DOR, duration of response; laBCC, locally advanced BCC; mBCC, metastatic BCC; NE, not estimable; ORR, objective response rate; PFS, progression‐free survival; TTR, time to tumour response.

Figure 3.

Objective response rates by central review across all BOLT (Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 Treatment) analyses in patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg daily.17, 19, 20 Results are for the intent‐to‐treat population. BCC, basal cell carcinoma; laBCC, locally advanced BCC; mBCC, metastatic BCC; ORR, objective response rate.

For the approved 200‐mg dose, the DCR exceeded 90% both in patients with laBCC and in those with mBCC (91% and 92%, respectively). For the 800‐mg dose, the DCR was 82·0% in patients with laBCC and 91% in patients with mBCC.

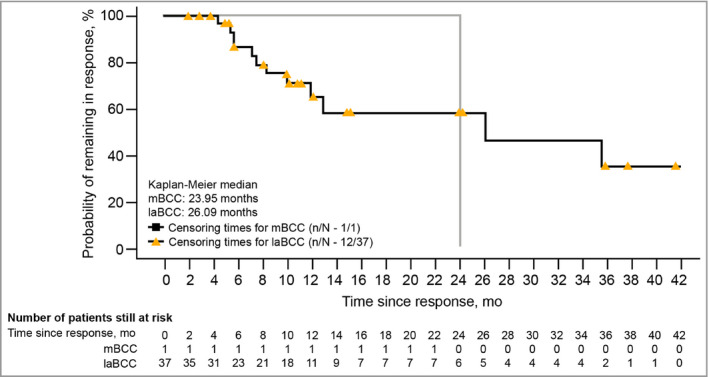

The median DOR for responders to the 200‐mg dose with laBCC was 26·1 months (95% CI not estimable; Table 1 and Fig. 4). Responses lasting 6 months or longer were seen in 23 of 37 responders with laBCC receiving sonidegib 200 mg (Fig. 5). There was one long‐term responder with mBCC in the 200‐mg group, whose DOR was 24·0 months (Fig. 4). For the 800‐mg arm, the median DOR was 23·3 months (95% CI 12·2–29·6) in patients with laBCC. For patients with mBCC, the median DOR in the 800‐mg arm was not estimable due to censoring of three of four responders.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier plots of duration of response per central review in patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg daily (responders only). BCC, basal cell carcinoma; laBCC, locally advanced BCC; mBCC, metastatic BCC; mo, months.

Figure 5.

Duration of response by central review in patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma receiving sonidegib 200 mg. Results are for the intent‐to‐treat population. CI, confidence interval.

Safety

The median durations of exposure to sonidegib were 11·0 months and 6·6 months for the 200‐mg and 800‐mg arms, respectively. Overall, 54 (68%), 34 (43%) and 19 (24%) patients were exposed to sonidegib 200 mg for ≥ 8, ≥ 12 and ≥ 20 months, respectively, whereas 65 (43·3%), 46 (30·7%) and 23 (15·3%) patients were exposed to sonidegib 800 mg for ≥ 8, ≥ 12 and ≥ 20 months, respectively.

Most AEs were manageable and reversible with dose interruptions or reductions. AEs in the 200‐mg group were primarily grade 1 or 2, with grade 3–4 AEs reported in 34 (43%) and 96 (64·0%) patients in the sonidegib 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively. Grade 3–4 AEs related to treatment were reported in 25 (32%) and 65 (43·3%) patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg and 800 mg, respectively. Grade 3–4 AEs led to discontinuation in 11 (14%) and 22 (14·7%) patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg and 800 mg, respectively. Serious AEs related to treatment were reported in four (5%) and 26 (17·3%) patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg and 800 mg, respectively. One (1%) and seven (4·7%) deaths occurred within 30 days of study treatment for the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively; none were suspected to be related to the study drug. The incidence of AEs in the approved 200‐mg group was similar to that observed in previous BOLT analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse events reported with sonidegib 200 mg across all BOLT analyses (n = 79)

| 6 months17 | 12 months19 | 18 months20 | 30 months20 | 42 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All AEs | 75 (95) | 77 (98) | 77 (98) | 77 (98) | 77 (98) |

| Grade 3–4 AEs | 24 (30) | 30 (38) | 31 (39) | 34 (43) | 34 (43) |

| All treatment‐related AEs | 68 (86) | 70 (89) | 70 (89) | 70 (89) | 70 (89) |

| Grade 3–4 AEs | 18 (23) | 22 (28) | 23 (29) | 24 (30) | 25 (32) |

| SAEs | 11 (14) | 13 (17) | 14 (18) | 16 (20) | 16 (20) |

| Treatment‐related SAEs | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 4 (5) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 17 (22) | 22 (28) | 24 (30) | 24 (30) | 24 (30) |

| AEs requiring dose interruption and/or reduction | 25 (32) | 30 (38) | 31 (39) | 34 (43) | 34 (43) |

The data are presented as n (%). Results are for the safety population. AE, adverse event; BOLT, Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 (sonidegib) Treatment; SAE, serious AE.

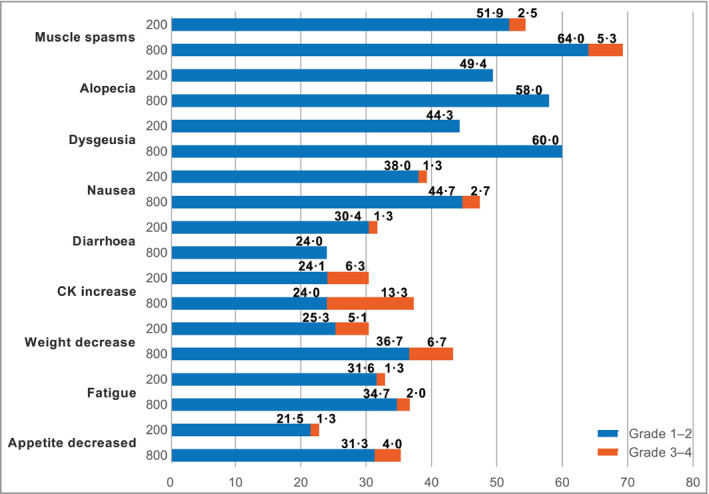

Overall, the most common AE by preferred term was muscle spasms, reported in 43 (54%) and 104 (69·3%) patients in the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively (Fig. 6). Alopecia was grade ≤ 2, reported in 39 (49%) and 87 (58·0%) patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg and 800 mg, respectively. The most common grade 3–4 AEs were elevated CK and elevated lipase (five patients, 6% each) in the 200‐mg group, and elevated CK (20 patients, 13·3%) in the 800‐mg group. The most common serious AEs were pneumonia (two patients, 3%) and elevated CK (six patients, 4·0%) in the 200‐mg and 800‐mg groups, respectively.

Figure 6.

Adverse events in ≥ 20% of patients treated with sonidegib 200 mg and 800 mg daily CK, creatine kinase.

In the 200‐mg arm, the AEs that most frequently led to treatment discontinuation were muscle spasms (four patients, 5%); asthenia, dysgeusia and nausea (three patients, 4% each); and fatigue, weight loss and decreased appetite (two patients, 3% each). The AEs that most frequently led to discontinuation in the 800‐mg arm included muscle spasms (12 patients, 8·0%), alopecia and weight loss (nine patients, 6·0% each), decreased appetite and dysgeusia (seven patients, 4·7% each), nausea (six patients, 4·0%), fatigue (four patients, 2·7%), dehydration and elevated CK (three patients, 2·0% each).

The most common AEs necessitating dose interruption in the 200‐mg arm included elevated CK, nausea and vomiting (five patients, 6% each); diarrhoea and elevated lipase (four patients, 5% each); and dysgeusia, fatigue and urinary tract infection (three patients, 4% each). In the 800‐mg arm, the most common AEs necessitating dose interruption or reduction included muscle spasms (28 patients, 18·7%), nausea (19 patients, 12·7%), elevated CK (18 patients, 12·0%) and dysgeusia and vomiting (12 patients, 8·0% each).

Discussion

In this final 42‐month analysis of the primary efficacy and safety results of the BOLT study, the clinical efficacy of sonidegib in patients with advanced BCC remained robust and consistent with earlier analyses. Sonidegib demonstrated sustained clinically relevant ORRs in laBCC per central review for both the 200‐mg and 800‐mg daily arms. Compared with results from the primary analysis at 6 months, the ORR for patients with laBCC was higher and similar to analyses performed at 12, 18 and 30 months (Fig. 3).17, 19, 20 Sustained response was confirmed, with a median DOR exceeding 2 years. ORR values were higher for patients with laBCC compared with mBCC, potentially due to the locations of the metastatic lesions (which could pose a challenge to accurate response assessment), the heterogeneity and aggressiveness of metastatic disease, and the extent of tumour burden. Of note, the DCR exceeded 90% in the 200‐mg group for both the laBCC and mBCC patient cohorts, indicative of treatment benefit in laBCC as well as mBCC.

The primary reasons for treatment discontinuation were consistent with previous analyses.17, 19, 20 The proportion of patients who discontinued study treatment because of AEs or patient's decision was higher in the 800‐mg group than in the 200‐mg group, whereas discontinuations due to disease progression were more frequent in the 200‐mg group. This could potentially be attributed to patients in the 200‐mg group being more likely to remain on treatment for longer periods until the time of disease progression.

Reported AEs were consistent with the known safety profile of sonidegib, with no new or late‐onset safety concerns emerging at 42 months. The safety and tolerability profiles of sonidegib 200 mg continued to be more favourable than those for sonidegib 800 mg, with lower overall incidences in each AE category. AEs in the 200‐mg group continued to be primarily grade 1 or 2, and most AEs were manageable and reversible with dose interruptions, with no overall impact on efficacy.

Vismodegib (Erivedge®, Genentech, San Francisco, CA), an HPI, is approved for the treatment of adults with mBCC or with laBCC that has recurred following surgery, or patients who are not candidates for surgery or radiation.21 In the phase II, single‐arm ERIVANCE BCC study, 71 patients with laBCC and 33 patients with mBCC were enrolled to receive 150 mg vismodegib once daily.22, 23 Final analysis at 39 months reported ORRs by investigator review of 60% (95% CI 47–72) and 49% (95% CI 31–66) in laBCC and mBCC, respectively.22 The most common AEs (percentage of patients) for the entire duration of the study included muscle spasms (71%), alopecia (66%) and dysgeusia (56%).22 Overall, 21% and 28% of patients discontinued the study due to AEs and disease progression, respectively.22 The single‐arm, open‐label multicentre STEVIE trial, which evaluated vismodegib 150 mg once daily in 1215 patients with laBCC or mBCC for a median treatment duration of 8·6 months (range 0–44), demonstrated similar safety results to ERIVANCE and the present study.24

Despite the demonstrated efficacy of sonidegib, study limitations include the small sample size of patients with mBCC, with 13 and 23 patients in the 200‐mg and 800‐mg arms, respectively. Together with the low number of responders in the mBCC cohort this made the estimation of DOR challenging. Additionally, the efficacy of sonidegib in patients with recurrent disease following prior therapy with an HPI is unknown, as these patients were excluded from the study.20 Another limitation is the tendency of patients with advanced BCC receiving an HPI to discontinue treatment due to low‐grade AEs that cause significant discomfort.19 Real‐world treatment plans with sonidegib should include management of AEs associated with HPI therapy, as well as patient education and intermittent therapy, which may also facilitate increased treatment duration, and therefore improve patient benefit. Results from the phase II MIKIE trial evaluating two intermittent dosing schedules of vismodegib in 229 patients with multiple BCCs support the feasibility of such therapeutic plans in this patient population.25

Overall, the 42‐month analysis of BOLT confirmed the durable efficacy of sonidegib for the management of laBCC and mBCC, with the approved 200‐mg dose continuing to demonstrate a better benefit‐to‐risk profile than the 800‐mg dose. No new safety concerns were discovered. Sonidegib continues to represent a viable treatment option for patients with advanced BCC.

Supporting information

Table S1 Demographics and baseline disease characteristics.

Conflicts of interest. R.D. receives grants and personal fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. A.G. has participated on advisory boards for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Regeneron and Sanofi; received honoraria from Novartis; and received travel support from Astellas, Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. R.G. serves as a consultant to Almirall, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Inc., Takeda and 4SC; has received travel grants and honoraria for lectures from Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; and has received research funding from Amgen, Johnson & Johnson, Merck Serono, Novartis and Pfizer. J.T.L. receives personal fees from Novartis and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. K.D.L. has received research funding paid to the institution from Novartis. A.L.S.C. is a primary investigator for, received a research grant or funding paid to the institution from, participated in an advisory board for, and received honoraria from Novartis. P.C. has no conflicts to disclose. L.D. participated in an advisory board for and received honoraria from Novartis. M.K. is a primary investigator for, participated in an advisory board for, and received honoraria from Roche Pharma, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Janssen. R.K. participated in an advisory board for and received honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Genentech. C.L. acted as a speaker for, participated in an advisory board for and received honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Roche, Novartis and Merck Sharp & Dohme. R.P. has participated on an advisory board and received honoraria from Astex, Roche, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Vertex, Bayer, Pierre Fabre, Novartis and Clovis Oncology. H.J.S. is a principal investigator for Novartis and received honoraria from Novartis paid to the institution. A.J.S. acted as a speaker for, participated in an advisory board for and received honoraria from Roche; participated in an advisory board for, received honoraria from, is a primary investigator for and received research funding from Novartis; acted as a speaker for, received honoraria from, is a primary investigator for and received a research grant from LEO Pharma; acted as a member of a steering committee and is primary investigator for Regeneron; and participated in an advisory board for Sanofi Genzyme. U.T. acted as an advisor for and received honoraria from Hofmann‐La Roche, participated in an advisory board for and received honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme, and acted as a speaker for and received honoraria from Novartis. N.S. is an employee of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. and receives honoraria from Galderma, LEO Pharma, Pierre Fabre, Novartis and Roche; consulting fees from Galderma, LEO Pharma, Pierre Fabre, Novartis and Roche; patents, royalties or other intellectual property from Genentech/F. Hoffmann‐La Roche, Ltd; and travel, accommodations or expenses from Galderma, LEO Pharma and Roche. M.R.M. has participated on advisory boards for and received honoraria from Genentech, Novartis, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Funding sources This study was sponsored and funded by Novartis, who was involved in the study design, data collection and data analysis. Writing and editorial support for manuscript preparation were provided by Ginny Feltzin, PhD, of AlphaBioCom, LLC, funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Princeton, NJ, U.S.A. All authors met the International Council of Medical Journal Editors criteria and received neither honoraria nor payment for authorship.

Conflicts of interest statements can be found in the Appendix.

References

- 1. Asgari MM, Moffet HH, Ray GT, Quesenberry CP. Trends in basal cell carcinoma incidence and identification of high‐risk subgroups, 1998–2012. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151:976–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xiang F, Lucas R, Hales S, Neale R. Incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer in relation to ambient UV radiation in white populations, 1978–2012: empirical relationships. JAMA Dermatol 2014; 150:1063–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B et al Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78:540–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amici JM, Battistella M, Beylot‐Barry M et al Defining and recognising locally advanced basal cell carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol 2015; 25:586–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lear JT, Corner C, Dziewulski P et al Challenges and new horizons in the management of advanced basal cell carcinoma: a UK perspective. Br J Cancer 2014; 111:1476–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scales SJ, de Sauvage FJ. Mechanisms of Hedgehog pathway activation in cancer and implications for therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2009; 30:303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mistretta CM, Kumari A. Tongue and taste organ biology and function: homeostasis maintained by hedgehog signaling. Annu Rev Physiol 2017; 79:335–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abe Y, Tanaka N. Roles of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in epidermal and hair follicle development, homeostasis, and cancer. J Dev Biol 2017; 5:E12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gailani MR, Stahle‐Backdahl M, Leffell DJ et al The role of the human homologue of Drosophila patched in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Nat Genet 1996; 14:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Knobbe CB et al Somatic mutations in the PTCH, SMOH, SUFUH and TP53 genes in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Weber RG et al Missense mutations in SMOH in sporadic basal cell carcinomas of the skin and primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer Res 1998; 58:1798–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Odomzo (sonidegib capsules) [full prescribing information]. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Cranbury, NJ, U.S.A., 2017.

- 13. European Medicines Agency . Summary of Product Characteristics, Odomzo. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/odomzo-epar-product-information_en.pdf (last accessed 14 October 2019).

- 14. ODDB . Odomzo 200mg. Swissmedic registration 65065. Available at: http://epilepsie-medikament.ch/en/gcc/show/reg/65065 (last accessed 15 October 2019).

- 15. Australian Government Department of Health . Odomzo. Sonidegib 200mg capsule. Available at: https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2017-PI-02511-1&d=2018030216114622483&d=201910141016933 (last accessed 14 October 2019).

- 16. Rodon J, Tawbi HA, Thomas AL et al A phase I, multicenter, open‐label, first‐in‐human, dose‐escalation study of the oral smoothened inhibitor sonidegib (LDE225) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20:1900–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Migden MR, Guminski A, Gutzmer R et al Treatment with two different doses of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BOLT): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:716–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Casey D, Demko S, Shord S et al FDA approval summary: sonidegib for locally advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23:2377–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dummer R, Guminski A, Gutzmer R et al The 12‐month analysis from Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 Treatment (BOLT): a phase II, randomized, double‐blind study of sonidegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75:113–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lear JT, Migden MR, Lewis KD et al Long‐term efficacy and safety of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced and metastatic basal cell carcinoma: 30‐month analysis of the randomized phase 2 BOLT study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32:372–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erivedge (vismodegib capsules) [full prescribing information]. Genentech, San Francisco, CA, U.S.A., 2019.

- 22. Sekulic A, Migden MR, Basset‐Seguin N et al Long‐term safety and efficacy of vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: final update of the pivotal ERIVANCE BCC study. BMC Cancer 2017; 17:332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE et al Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal‐cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Basset‐Seguin N, Hauschild A, Kunstfeld R et al Vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: primary analysis of STEVIE, an international, open‐label trial. Eur J Cancer 2017; 86:334–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dreno B, Kunstfeld R, Hauschild A et al Two intermittent vismodegib dosing regimens in patients with multiple basal‐cell carcinomas (MIKIE): a randomised, regimen‐controlled, double‐blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18:404–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Demographics and baseline disease characteristics.