Abstract

Partnering across health clinics and community organisations, while worthwhile for improving health and well‐being, is challenging and time consuming. Even partnerships that have essential elements for success in place face inevitable challenges. To better understand how cross‐organisational partnerships work in practice, this paper examines collaborations between six primary care clinics and community‐based organisations in the United States that were part of an initiative to address late‐life depression using an enhanced collaborative care model (Archstone Foundation Care Partners Project). As part of an evaluation of the Care Partners Project, 54 key informant interviews and 10 focus groups were conducted from 2015 to 2017. Additionally, more than 80 project‐related documents were reviewed. Qualitative thematic analysis was used to code the transcripts and identify prominent themes in the data. Examining clinic and community organisation partnerships in practice highlighted their inherent complexity. The partnerships were fluid and constantly evolving, shaped by a multiplicity of perspectives and values, and vulnerable to unpredictability. Care Partners sites negotiated the complexity of their partnerships drawing upon three main strategies: adaptation (allowing for flexibility and rapid change); integration (providing opportunities for multi‐level partnerships within and across organisations) and cultivation (fostering a commitment to the partnership and its value). These strategies provided opportunities for Care Partners collaborators to work with the inherent complexity of partnering. Intentionally acknowledging and embracing such complexity rather than trying to reduce or avoid it, may allow clinic and community collaborators to strengthen and sustain their partnerships.

Keywords: collaborative care, depression, evaluating complex interventions, multi‐sector collaborations, older adults, qualitative research

What is known about this topic

Call for primary care clinics to partner with community‐based organisations (CBOs).

A number of essential factors of successful partnerships have been identified.

Even with these essential factors in place, cross‐organisational partnerships often struggle.

What this paper adds

Examining primary care clinic and CBO partnerships in practice highlights their inherent, often unacknowledged, complexity.

We highlight three strategies clinics and CBOs relied upon to negotiate complexity—adaptation, integration and cultivation.

Our results suggest partnering organisations should acknowledge complexity and develop strategies to work with the unpredictability and fluidity inherent to cross‐organisational partnerships.

1. INTRODUCTION

Partnership has become increasingly relevant in the delivery of healthcare services over the last few decades, and millions of dollars have been invested in collaborative approaches to address complex health issues in the United States and other countries (Dickinson & Glasby, 2010; Lasker, Weiss, & Miller, 2001; Mervyn, Amoo, & Malby, 2019; Radermacher, Karunarathna, Grace, & Feldman, 2011; Romm & Ajayi, 2017; San Martín‐Rodríguez, Beaulieu, D’Amour, & Ferrada‐Videla, 2005). A 2012 report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM), for instance, calls for enhanced collaboration among public, private, healthcare and non‐healthcare sectors as a means to improve chronic disease prevention and treatment. More recent reports from the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the IOM) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine specifically recommend collaboration between social service agencies and medical care clinics to serve socially at‐risk and high‐need patients, 55% of whom are age 65 or older (Long et al., 2017; NASEM, 2019). Other studies have echoed recommendations for cross‐sector collaboration, calling for more collaboration between primary care clinics and social service agencies or community‐based organisations (CBOs) to address social determinants of health (e.g. economic stability, education, community and physical environment, food security and nutrition, social supports), which have traditionally been considered outside the purview of the medical system (Leutz, 1999; Miranda et al., 2013; Predmore, Hatef, & Weiner, 2019; Warburton, Everingham, Cuthill, & Bartlett, 2008).

Since 2011, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in the United States has been critical in driving collaboration between medical providers and healthcare organisations to better coordinate services through the establishment of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) (Bailit, Tobey, Maxwell, & Bateman, 2015). Some ACOs have expanded the focus on medical care coordination to include services that address social and behavioural issues. These approaches have shown promising early results lending support to the value and viability of partnerships between healthcare providers and CBOs (Bailit et al., 2015; Maxwell, Barron, Bourgoin, & Tobey, 2016). Despite some healthcare organisations and systems moving in this direction, service delivery models that integrate medical, social and other services remain relatively uncommon.

Clinic and social service agency partnerships have a number of assumed benefits, including more innovative and systemic solutions to complex health issues, stronger alignment and more efficient use of resources, and improved quality and coordination of patient care (Brinkerhoff, 2002; Lasker et al., 2001; Marek, Brock, & Salva, 2015). Although these partnerships have potential benefits, many dissolve within 1 year of their outset, and even those that do last longer often struggle through the planning and implementation stages of collaborative interventions (Dickinson & Glasby, 2010; Lasker et al., 2001; Marek, Brock, & Savla, 2015). One challenge is partnerships require individuals and organisations to change the ways they have traditionally worked, and this shift is not only time consuming and resource intensive, but can be met with resistance at the individual or organisational level (Lasker et al., 2001). Additional challenges to partnerships, especially those which require changes in workflows or added staff responsibilities, can include issues of turf and territoriality, inadequate resources to support collaborative efforts, and lack of buy‐in from key stakeholders (Casado et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2006; Lester et al., 2007; Walshe, Caress, Chew‐Graham, & Todd, 2007; Weiner & Alexander, 1998).

Considering the mounting importance and yet challenging nature of collaboration, researchers have identified characteristics or protective factors that can support strong partnerships. Among the identified factors are a history of collaboration, mutual trust and respect, shared ownership of the partnership and its outcomes, and strong leadership (Cobb, Haisman‐Smith, & Jordan‐Daus, 2017; Jones & Barry, 2011; Mattessich & Monsey, 1992; Warburton et al., 2008; Weiss, Anderson, & Lasker, 2002). Many of these factors overlap with tenets of multi‐sector collaborations and community‐based participatory research (Bromley et al., 2018; Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel, & Minkler, 2018). While a list of factors can aid our understanding of foundational elements of partnership, the focus on a set of distinct and seemingly static characteristics can obscure the ways partnerships actually unfold in practice. Partnerships rarely occur in linear, predictable or independent ways. Rather, they consist of individuals interdependently navigating stated and unstated rules and expectations within a larger system. These characteristics suggest cross‐organisational partnerships may be best understood through the lens of complexity (Braithwaite, Churruca, Long, Ellis, & Herkes, et al., 2018; Williams & Hummelbrunner 2010).

Complex relationships or activities can be identified by their non‐linear, emergent and fluid nature. They are also shaped by contextual rules, inter‐relationships and often amorphous boundaries (Plsek & Greenhalgh, 2001; Williams & van't Hof, 2016; Zimmerman, Lindberg, & Plsek, 1998). As researchers in this area suggest, complex activities are unique from difficult or complicated activities. Complicated situations may require significant levels of knowledge, skill and resources to address, but there are predictable steps to resolve challenges. In contrast, complex activities do not necessarily require special expertise or technical acumen, but they are inherently unpredictable and difficult to control. For example, launching a rocket is complicated, whereas raising a child is complex (Glouberman & Zimmerman, 2002; Patton, 2011; Westley, Zimmerman, & Patton, 2006).

In this paper, we use the lens of complexity to better understand the challenges and opportunities of partnering work. Drawing upon data from an evaluation of primary care clinic and CBO partnerships, we examine three qualities of partnering which highlight their fluid, emergent and unpredictable nature. We also explore three approaches the clinic‐CBO partnerships employed to navigate the complexities they faced.

2. METHODS

2.1. Background on the Care Partners Project

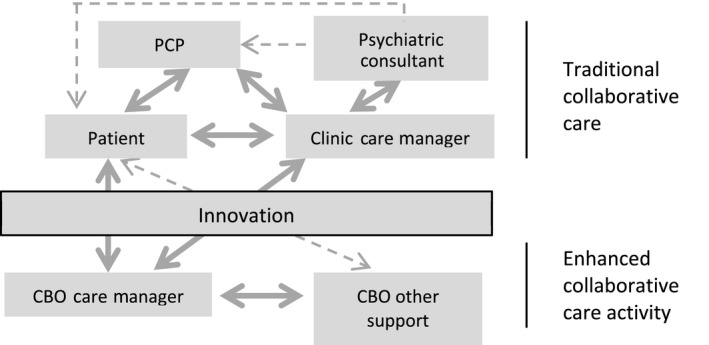

To explore the dynamics of partnerships in practice, we examined the Archstone Foundation Care Partners Project, a multi‐site initiative of clinic‐CBO partnerships in the United States. The 3‐year initiative, which began in 2015, funded six primary care clinic‐CBO partnerships, or what we will refer to as sites, to implement an enhanced collaborative care program. In the program, primary care providers (PCPs), supported by care managers and psychiatric consultants, work with partners in community organisations to address late‐life depression. The general model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model of enhanced collaborative care with the addition of the community‐based organisation (CBO). Clinic Care Manager: Provides evidenced‐based depression treatment to patients such as behavioral activation. CBO Care Manager: Offers support services to the patient, which may include housing and social service support. Also, may provide depression treatment to patients. Primary Care Provider (PCP): Works with clinic care manager to assess, monitor, and treat patient’s depression. Treatment may include medication management. Psychiatric Consultant: Communicates with the clinic and CBO care managers (through regular meetings) and PCP (often through the care manager or medical records) to provide diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations including medication management

The program was designed at each site to incorporate key elements of depression care, including tasks such as depression screening and diagnosis, recruitment of eligible patients, patient and family education, care management, delivery of evidenced‐based behavioural interventions, medication management, referral to specialty services, and follow‐up with patients. In a traditional collaborative care model, many of these tasks are carried out in the primary care setting by care manager(s) and PCPs with support from a psychiatric consultant (Unützer et al., 2002). In the Care Partners Project, this traditional model was enhanced through the addition of CBO care managers and support staff, who shared tasks and accountability around depression care. Depending on the partnership agreement, CBO care managers had a variety of roles and functions, including providing case management to address unmet needs and meeting with older adults in the community.

The primary care clinics included academic primary care centres and Federally Qualified Health Centres serving low‐income populations. CBOs offered a range of services to older adults including health education, free lunches, social opportunities, psychotherapy and case management. Collaborative care training and development at each site was supported by practice coaches and researchers from the AIMS (Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions) Center at the University of Washington. The partnering sites were located throughout California, United States. Some of the sites had previously established partnerships, although none had collaborated around depression care specifically.

2.2. Data collection

Qualitative data were collected as part of an evaluation of the Care Partners Project through interviews, focus groups, and document analysis. Fifty‐four key informant interviews were conducted in 2016 and 2017. Four to five key informants such as care managers, administrators and PCPs were purposively sampled from each site based on their active involvement in the planning or delivery of the Care Partners Project. Seventeen key informants (eight care managers, six administrators, three PCPs) were interviewed in both time periods, whereas 20 individuals (nine care managers, six administrators, five PCPs) were interviewed only one time because they were not involved in the project for both years. Key informants were recruited through an email. All individuals who were asked agreed to be interviewed. Interviews were conducted by the evaluation team (PhD‐ and MD‐level researchers with experience in qualitative methods) using a semi‐structured interview guide. The guide included questions about participants’ roles on the project, their experiences partnering with others, and Care Partners successes and challenges. The 45‐ to 60‐min interviews were conducted by phone, digitally recorded and professionally transcribed.

In addition to interviews, 10 focus groups with Care Partners leadership, clinicians and staff were held at 3 time points from 2015 to 2017. Focus groups lasted approximately 60–90 min and included questions about the planning and delivery of the intervention, experiences of partnering with another organisation, and organisational changes that occurred as a result of the initiative. Focus group participants were divided by their role in the Care Partners Project.

A third data collection approach was a review of over 80 Care Partners documents collected over the course of the initiative (2015–2017). The documents included initial grant proposals, quarterly and annual progress reports submitted by the sites, and notes from calls with the AIMS Center, which provided coaching and technical assistance for the sites. The Institutional Review Boards of the evaluation and technical assistance teams’ institutions determined the evaluation of the initiative was quality improvement and thus, exempt from human subjects review. However, we followed human subject protocol and obtained verbal consent for interviews and focus groups.

2.3. Data analysis

The evaluation team used the qualitative analytic approach of thematic analysis to code the transcripts and identify prominent themes (Bernard & Ryan, 2010; Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007). QSR International's NVivo 11 (released 2015), a qualitative data analysis software program, was used to organise and code the data. Since the data sources varied and the amount of data collected was large, several stages of analyses were undertaken. First, four coders from the evaluation team reviewed the data broadly to identify initial codes. Some of the codes were determined a priori based on past work in this area. Other codes emerged from the analysis process. Throughout the process, the evaluation team wrote analytic memos and continuously discussed and reviewed the data to expand, refine and validate initial codes (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014; Saldaña, 2016).

The first round of coding led to the development of a matrix which provided an overview of each partnership and its characteristics (Miles et al., 2014). For the second stage of analysis, the evaluation team used the matrix to identify connections between codes and find patterns in the data. This process led to the identification of prominent themes, including those which are described in this paper. Throughout the analysis process, to increase and assure the reliability and validity of the codes and themes, the evaluation team shared and discussed key findings with the technical assistance team.

3. FINDINGS

3.1. Complexity of cross‐organisational partnerships

The development of partnerships in the Care Partners Project was, as expected, challenging. Implementing many elements of the intervention required individual‐level coordination as well as changes to the broader organisations. Incorporating a partner organisation into depression care workflows meant taking on new or expanded roles and responsibilities for some individuals. For example, some CBO care managers were tasked with assessing patients’ depression through a standardised screening tool, which was often a new function for them. Resource and information sharing also complicated the new collaborations. A CBO participant, for instance, reflected on the challenges of gaining read and write access to the electronic medical record:

[I]t took a lot of effort for [the care manager] to have access to the medical record. All the IT [information technology] issues were complicated and it took having two organizations working together to resolve those issues. And not only the IT issue, but the authorization issue, the confidentiality issue. (Site 1)

Although these aspects of partnering proved complicated, partnering sites were able to resolve workflow and data‐sharing issues by establishing memorandums of understanding and using the care management registry created by the AIMS Center for program communication and tracking.

Overlaying these complicated tasks, we found the broader activity of partnering—how it was understood and acted upon—was complex. Viewed within a framework of complexity (adapted from Williams & van't Hof, 2016), Care Partners collaborations were fluid and constantly evolving, shaped by a multiplicity of perspectives and values, and vulnerable to unpredictability. This section describes these characteristics of complexity and how they presented in practice.

3.1.1. Fluid partnership boundaries

On the surface, the boundaries in the Care Partners Project—who the partners were and who was involved—appeared clear. At each Care Partners site, the program involved administrators, care managers, lead PCPs, psychiatric consultants, community health workers and social workers. At a broader level, the partnerships relied on significant decision‐makers such as organisational leadership who oversaw policy, resources and staffing.

In addition, the intervention often required involvement of individuals who were outside the bounds of the core partnership but who played critical roles in the delivery of depression care. For example, some partnerships relied on medical assistants, PCPs other than the lead provider, and mental health providers to help identify, recruit or engage patients in the intervention. However, these individuals were not involved in decision‐making and often unaware of the ways their day‐to‐day work connected to the broader initiative. A care manager commented on the challenges of adding additional partners to the intervention:

Coming on, I expected it to be a very smooth – a very smooth process… I was surprised to see how difficult it was to get everyone on board. Whether it be providers, other staff, even the patients… And the barriers that came into play as we were going along. So, that was a big surprise to me, actually. (Site 2)

This reliance on staff with ancillary roles within the program, while potentially helpful, contributed to the complexity of carrying out the partnered intervention, as these actors varied widely in their levels of buy‐in, awareness and engagement, and understanding of the need for or value of a new approach.

Also involved in the initiative were technical assistance staff, the funder and evaluators who supported the program. These outside partners assisted sites and suggested adaptations to improve care delivery. They also influenced the relationship dynamics and interactions between clinic and CBO partners, even though they were on the periphery of the cross‐organisational partnerships.

In practice, the very idea of partnership and who was a partner was amorphous and fluid as individuals’ involvement varied. The changing dynamic of individuals involved affected Care Partners planning, communication, decision‐making and the overall progress of the intervention.

3.1.2. Multiple perspectives

Beyond the fluidity of boundaries and uncertainty around the respective roles of central and peripheral partners, a related factor contributing to the complexity of clinic‐CBO partnerships was the multitude of perspectives, values and cultures individual actors and the organisations brought to the partnerships. Even when individuals knew they were in a partnership, they viewed their partnership activities through their particular discipline‐based lens. For example, PCPs at some sites were balancing the intervention with other programs within their organisations and did not always understand the value offered by their clinic's partnership with a CBO, leading to reluctance to prioritise the program, particularly considering their already limited time with patients. This more limited level of engagement in and perceived value of the intervention was counter to others who had a more central role on the project, such as care managers who at most sites had been hired specifically to carry out the Care Partners Project. A PCP champion commented on the varying levels of value the transition to collaborative care with a CBO partner held for PCPs in their organisation:

[The care manager] is excellent, and…having her engage with patients is really helpful. But aside from that…we have excellent psychiatric services on site. And there’s reticence among the providers to stray from that. (Site 2)

The perspective through which individuals saw the intervention also was influenced by the distinct organisational cultures of the Care Partners sites. Differences in organisational culture affected the pace, style and priorities of the partnering organisations. For instance, in a focus group of clinic administrators, one participant commented:

To sum it up, it’s just two different cultures. We’re in a medical setting where things are really fast‐paced. And people respond really quickly, things get done. And with the collaborating thing that we’re working with, things are a little bit more relaxed. They actually serve their seniors [meals], so everyone’s mingling and they’re not in front of their computers… It’s a very different culture and [we’re] coming to that realization, being okay with that flexibility. (Site 3)

Cultural differences between partnering agencies surfaced in a variety of ways, through organisational bureaucracy as well as underlying values of cross‐sector collaboration and depression care. For example, an administrator from a small CBO commented on the challenges of collaborating with a larger, more bureaucratic organisation:

We are a community‐based organization. We do things different than a clinic does… [the clinic] is too big and they have a lot of protocols they have to follow. So, it takes time. Takes process. They have to go through one, two, three, four, five [steps]… that was the challenge. (Site 4)

Although most sites were eventually able to find common ground, the variety of perspectives and organisational cultures that made up the partnerships led to conflicting foci, values and views of the intervention among the partners.

3.1.3. Unpredictability of partnering

Partnering for Care Partners sites was also complex because of the unpredictability of individual and organisational relationships and turnover. While the partnerships were created at the leadership or organisational level, in practice the intervention occurs not between organisations but rather is developed through individual relationships, such as those between care managers, clinicians and administrators. In many cases these relationships contributed to strong collaborations with mutual trust and respect between partners. Even with established trust, however, the partnerships were vulnerable to the unpredictability inherent to interpersonal interactions. At times, seemingly minor misunderstandings or changes in structure created disruptions in workflow and communication between partners. For example, a CBO care manger discussed the disruption of their referral process when they provided clarification of patient eligibility criteria to providers at the partnering clinic:

[Receiving referrals from the clinic] was difficult. Sometimes, we’d get referrals for clients who had needs that we weren’t able to serve because of either language or mental capacity. And so then we’d have to come back and say, “Sorry, we actually can’t serve this client” and that would usually slow down referrals for a little while. (Site 5)

Staff turnover also highlighted the vulnerability of partnerships throughout Care Partners program implementation and delivery. A clinic administrator described how turnover added uncertainty to their partnership with the CBO:

We had some turnover. And… that’s always interesting and can sink a project. If you have a key member of a team who moves onto other activities, you never know when new personalities and people come in part way through a project, whether they’re actually dedicated to it. (Site 1)

Turnover created instability, which made the partnerships unpredictable in multiple ways—first, changes in staffing interrupted workflows, which in some cases led to neglected tasks or new responsibilities for the remaining partners; second, turnover forced the partners to re‐establish relationships within and across organisations.

3.2. Navigating complexity in partnerships

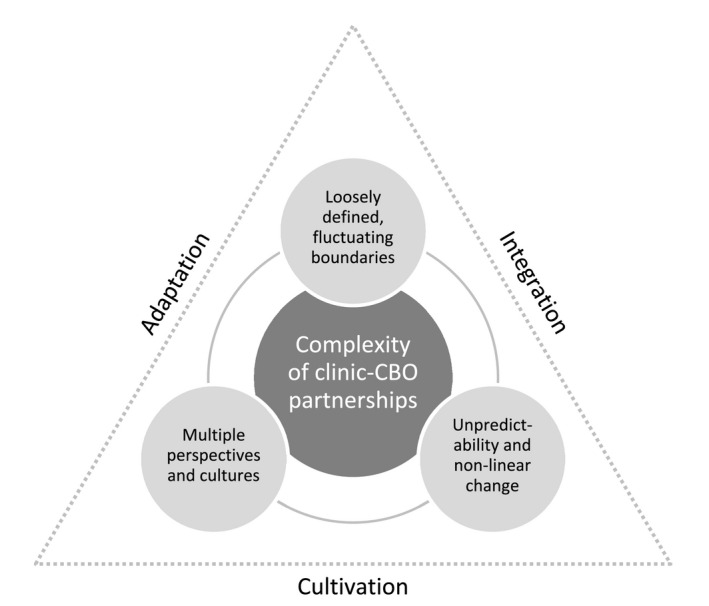

The previous section highlighted the uncertain, amorphous and evolving qualities of cross‐organisational partnering. In this section we examine the strategies Care Partners organisations employed to negotiate the complexity inherent within their partnerships (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram of the relationship between cross‐organisational complexity and navigation strategies

3.2.1. Adaptation

The primary approach Care Partners sites used to manage the complexity they encountered was to adapt the project to changing circumstances. As part of the initiative, sites were encouraged to continuously monitor program outcomes and make real‐time adjustments. Adaptations occurred at multiple levels: sites reorganised partners’ roles, modified intervention activities or renegotiated agreements between organisations. An early adaptation many sites had to make was re‐assigning tasks and expanding the boundaries of their partnership to improve the identification and engagement of patients. For instance, to streamline the recruitment process, some sites initially limited the referral process to a core group of staff, such as a single PCP or care manager. However, over time several sites shifted their approach to more intentionally engage non‐core actors in the intervention. For example, a care manager commented:

So, we had a very slow start. And we tried to figure out, like, what would work best. And what’s working now for us is having our behavioural health team involved. So, not just members of the team that were specifically asked to participate in the [Care Partners] program, but also our case managers, other case managers at [the CBO], having more hands involved, because those patients already have built a relationship with those people… So, having more people involved with getting patients involved with this care has been very, very, very helpful with our delivery of the program here. (Site 2)

Several sites also adapted their partnered approach to depression care to enhance the program's accessibility for patients and their families, for example, by placing increased emphasis on connecting with patients through phone calls and community outreach. One site, which had originally planned for their patients’ family members to receive depression education at the CBO, moved the courses to the clinic because of low attendance. As a care manger explained:

Part of the original game plan was that [the CBO] has all these transportation capabilities and… [could] cart people around to, like, the clinic and bring them into the therapy centre and stuff. But because a lot of our patients don’t live in the official catchment area, they can’t do that. So, we had to figure out how to bring some of those services, what they offer, over directly to the clinic where the patients who are already familiar are coming. So, we ended up moving all the caregiver classes over to the clinic, still delivered by [the CBO], but onsite here. (Site 6)

The ability of sites to adapt to challenges often depended on their willingness to be flexible and persist in the partnership. For example, a CBO care manager described the main lesson of their partnership:

To not give up. Keep trying. If it doesn’t work right one way, try another way. That willingness goes a long way… [I]f there’s willingness on both sides, there’s generally a way to make it work. And there was always willingness, and even at this stage now where there’s some challenges in the transition, I can still feel the willingness. (Site 1)

3.2.2. Integration

A second approach Care Partners sites adopted to navigate partnership complexity was to establish team integration, reflected by shared decision‐making and communication across multiple organisational levels. The degree of integration varied and strong leadership was an important component of it. Most clinics and CBOs were able to create linkages between administrators, care delivery staff and PCPs. In these cases, there was strong integration in which individuals connected not only with their counterpart in the other organisation (e.g. administrator with administrator), but also between positions across both organisations. For instance, one site's integrative approach allowed them to develop a strong foundation of cross‐professional and cross‐site communication, providing opportunities to manage multiple perspectives and unpredictability when it arose.

Conversely, some sites’ teams were partially integrated. These sites had, for example, strong linkages and communication between care managers at the clinic and CBO, but had more limited connections across levels, such as between care managers, administrators and PCPs. For instance, in one site, inconsistent communication between the care managers and PCPs made the identification and recruitment of patients for the intervention challenging. Under partial integration, partnering organisations’ abilities to develop new ideas, make change, and incorporate divergent views (i.e. to negotiate complexity) were hindered. Sites with partial integration were also more susceptible to disruptions caused by turnover as the lack of knowledge exchange made it difficult for others to quickly step into new roles or responsibilities.

3.2.3. Cultivation

Sites also negotiated the complexity of partnering by cultivating a unique Care Partners identity. The partnerships, especially early in the implementation, were loosely defined and not well integrated in either the broader clinic or CBO workflows. For the majority of sites, this situation led to inconsistent engagement and communication challenges. Thus, an initial task was to develop a specific identity for the program and promote its value to both core and non‐core actors as well as patients. Cultivation of a program identity was especially important since the intervention at all sites was relatively small‐scale and competing with other organisational priorities.

Sites engaged in activities that cultivated a project identity, such as creating a project vision statement and participating in regular team meetings. Commenting on the role of meetings in bringing cohesion to the partnership, a CBO administrator said:

I think that we have gotten to know each other more on a personal level and can put names to faces…. It's definitely made things better and I think that we learn more about what they do and they learn more about what we do. So, even outside of the project, there's more referrals to things. (Site 5)

Proximity of the partnering organisations also helped sites cultivate a partnered identity and established opportunities for warm handoffs. For example, one site provided clinic office space for the care manager from the CBO. Two other sites had the CBO care managers come to the clinic regularly after seeing the need for a stronger program identity. A CBO care manger explained the rationale:

We said, gee, we really like the idea of having someone from one of the organizations be present at the other organization, at least one day a week…. So, that people could have contact with [the CBO], like, put a face on the organization, as opposed to having people over there [at the clinic] just say, ‘Oh, you need to contact somebody from [the CBO]’. (Site 2)

In terms of negotiating complexity, cultivating a strong, distinct Care Partners identity allowed sites to articulate their vision and values to a wide range of stakeholders (e.g. patients and non‐core actors).

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings confirm that cross‐organisational partnerships are challenging, although they are challenging in ways previous literature does not fully address. Using ideas from complexity theory as a lens to view partnerships in practice, we identified three qualities which highlight their underlying complexity—fluidity of boundaries, multiplicity of perspectives and values among stakeholders, and unpredictability. We also identified three interdependent strategies organisations used to manage the complexity of their partnerships—adaptation, integration and cultivation.

Our exploration of clinic‐CBO partnerships confirmed the importance of many factors identified in the literature as predictors of effective collaboration. For example, the importance of building trust and respect among partners was reflected in the process of cultivating a shared identity as well as in integrating decision‐making processes across organisational levels (Aarons et al., 2014; Butt, Markle‐Reid, & Browne, 2008; Lester et al., 2007). We also observed the value of strong but shared leadership and consistent involvement of administrators in managing complexity that arose around diverse stakeholder views, turnover and unforeseen disruptions (Brinkerhoff, 2002; Carmola Hauf & Bond, 2012; Douglas, 2009). However, even with careful planning of workflows, seemingly clear delineation of roles and responsibilities, and assumed common understanding of the initiative across partnering organisations, we found cross‐organisational partnerships have some level of inherent uncertainty and unpredictability that can disrupt original plans.

While some studies acknowledge the complexity of partnering, the literature around partnership effectiveness has not thoroughly appreciated the degree of influence complexity may have on the outcomes of a partnered initiative. The common strategy of delineating factors that facilitate partnership success implies a greater level of control over the emergent conditions of partnership than stakeholders may have. In practice, although organisational leaders can control many aspects of how the partnership will progress and what outcomes it will achieve, there will be significant interactional‐ and system‐level happenings outside of their control (Zimmerman et al., 1998). Acknowledging complexity and its potential to impact partnership processes and outcomes, while it does not solve inevitable partnership challenges, may allow organisations and their managers to be more intentional about ways they can address disruptions that arise out of complexity (Patton, 2011).

The approaches Care Partners sites used to negotiate complexity paralleled strategies identified by complexity science and systems researchers who suggest flexible, decentralised or distributed control is more effective than rigid centralised control to address complexity (Plsek & Greenhalgh, 2001; Williams & van't Hof, 2016; Zimmerman et al., 1998). Rather than solving specific challenges related to complexity, they highlight establishing an environment that can nimbly adjust to change. Furthermore, our findings are broadly consistent with emerging models in implementation science, which emphasise systems‐level and complexity‐informed approaches to implementation (Braithwaite et al., 2018; Butt et al., 2008).

For Care Partners sites, the complexity of partnering affected the implementation and delivery of the intervention. For example, some sites struggled initially to balance tasks associated with partnership development and depression care delivery. In this sense complexity may have implications for the development and success of partnered initiatives. However, the extent to which complexity and the ability to tolerate complexity influence the outcomes of a partnership remains unclear. Despite its potential to create challenges in implementation and tension between partners, complexity is not inherently negative. For example, while involving a multitude of stakeholders led to some challenges throughout Care Partners implementation, the project also benefitted from the diverse perspectives and capacities of the range of actors. Our results suggest partnering organisations should aim to manage and skilfully navigate complexity within their partnerships but not try to eliminate it completely. Some level of complexity will inevitably be present in collaborative initiatives, but an awareness of partnership qualities which contribute to complexity and a willingness to build capacities to adjust to it may support partnership effectiveness and sustainability. These findings can help guide recent interest in the United States on healthcare systems taking more of a leadership role in addressing social care needs as they feel pressure from value‐based payment programs to improve quality and reduce costs.

4.1. Limitations

The Care Partners Project focused on clinic‐CBO partnerships implementing an evidence‐based depression program, thus, our findings may not be generalisable to all types of partnerships or programs. Partnerships in other sectors or with different structures may face challenges or complexities different from those which surfaced in the Care Partners Project. Additionally, our goal was to focus on how partnerships unfolded in practice, therefore we did not attempt to evaluate partnerships’ outcomes in this paper.

5. CONCLUSION

Examining the Care Partners Project shows the importance of acknowledging and anticipating the complexity inherent to cross‐organisational partnerships. As partnering expands in the planning and delivery of healthcare services at a community level in the United States and other countries, healthcare leaders and practitioners must continue to expand their ideas and approaches to partnering work, including as necessary reframing their organisational values and operations. As we explore in this paper, partnerships often play out differently in practice than how they are conceptualised. Basic taken‐for‐granted ideas of partnership, for example who is partnering, how partnering is viewed, and how the partnership will evolve, are not as stable or controllable as often assumed. The fluidity and unpredictability of partnerships suggest organisations need to develop capacities to actively engage in and embrace complexity.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported through a grant provided by the Archstone Foundation (14‐04‐71). We thank the Care Partners organisations and their staff for their participation in the research. We also thank Thuc‐Nhi Nguyen for assistance with data collection and analysis, Duyen Tran and Mai Nguyen for research assistance, and Ashley Heald, Mindy Vredevoogd and Katherine James for providing Care Partners technical assistance and research support.

Henderson S, Wagner JL, Gosdin MM, et al. Complexity in partnerships: A qualitative examination of collaborative depression care in primary care clinics and community‐based organisations in California, United States. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28:1199–1208. 10.1111/hsc.12953

REFERENCES

- Aarons, G. A. , Fettes, D. , Hurlburt, M. , Palinkas, L. , Gunderson, L. , Willging, C. , & Chaffin, M. (2014). Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescence for interagency‐collaborative teams to scale‐up evidence‐based practice. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 915–928. 10.1080/15374416.2013.876642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailit, M. , Tobey, R. , Maxwell, J. , & Bateman, C. (2015). The ACO conundrum: Safety‐net hospitals in the era of accountable care. Boston, MA: JSI Research & Training Institute; Retrieved from http://www.bailit-health.com/articles/2015-0504-bhp-jsi-rwjf-aco-conundrum.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H. R. , & Ryan, G. W. (2010). Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, E. H. , Curry, L. A. , & Devers, K. J. (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42, 1758–1772. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, J. , Churruca, K. , Long, J. C. , Ellis, L. A. , & Herkes, J. (2018). When complexity science meets implementation science: A theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Medicine, 16, 63 10.1186/s12916-018-1057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2002). Assessing and improving partnership relationships and outcomes: A proposed framework. Evaluation and Program Planning, 25, 215–231. 10.1016/S0149-7189(02)00017-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, E. , Figueroa, C. , Castillo, E. G. , Kadkhoda, F. , Chung, B. , Miranda, J. , … Kataoka, S. H. (2018). Community partnering for behavioral health equity: Public agency and community leaders' views of its promise and challenge. Ethnicity & Disease, 28(Suppl 2), 397–406. 10.18865/ed.28.S2.397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt, G. , Markle‐Reid, M. , & Browne, G. (2008). Interprofessional partnerships in chronic illness care: A conceptual model for measuring partnership effectiveness. International Journal of Integrated Care, 8, e08 10.5334/ijic.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmola Hauf, A. M. , & Bond, L. A. (2012). Community‐based collaboration in prevention and mental health promotion: Benefiting from and building the resources of partnership. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 4, 41–54. 10.1080/14623730.2002.9721879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casado, B. L. , Quijano, L. M. , Stanley, M. A. , Cully, J. A. , Steinberg, E. H. , & Wilson, N. L. (2008). Healthy IDEAS: Implementation of a depression program through community‐based case management. The Gerontologist, 48, 828–838. 10.1093/geront/48.6.828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, W. , Haisman‐Smith, N. , & Jordan‐Daus, K. (2017). Empowering positive partnerships: A preview of the processes, benefits and challenges of a university and charity social and emotional learning partnership. Teacher Advancement Network Journal, 9, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, H. , & Glasby, J. (2010). Why partnership working doesn’t work. Public Management Review, 12, 811–828. 10.1080/14719037.2010.488861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, A. (2009). Partnership working. London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Glouberman, S. , & Zimmerman, B. (2002). Complicated and complex systems: What would successful Medicare look like? Discussion paper 8. Ottawa, Ontario: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. , Franklin, C. , Butler, B. , Williams, P. , Wells, K. , & Rodriguez, M. A. (2006). The building wellness project: A case history of partnership, power sharing, and compromise. Ethnicity & Disease, 16, 54–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. , & Barry, M. M. (2011). Exploring the relationship between synergy and partnership functioning factors in health promotion partnerships. Health Promotion International, 26, 408–420. 10.1093/heapro/dar002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker, R. D. , Weiss, E. S. , & Miller, R. (2001). Partnership synergy: A practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Millbank Quarterly, 79, 179–205. 10.1111/1468-0009.00203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester, H. , Birchwood, M. , Tait, L. , Shah, S. , England, E. , & Smith, J. O. (2007). Barriers and facilitators to partnership working between early intervention services and the voluntary and community sector. Health and Social Care in the Community, 15, 493–500. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutz, W. N. (1999). Five laws for integrating medical and social services: Lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Milbank Quarterly, 77, 77–110. 10.1111/1468-0009.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, P. , Abrams, M. , Milstein, A. , Anderson, G. , Lewis Apton, K. , Lund Dahlberg, M. , & Whicher, D. (2017). Effective care for high‐need patients: Opportunities for improving outcomes, value, and health. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek, L. I. , Brock, D. P. , & Savla, J. (2015). Evaluating collaboration for effectiveness: Conceptualization and measurement. American Journal of Evaluation, 36, 67–85. 10.1177/1098214014531068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattessich, P. W. , & Monsey, B. R. (1992). Collaboration: What makes it work. A review of the research literature on factors influencing successful collaboration. St. Paul, MN: Amherst H. Wilder Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. , Barron, C. , Bourgoin, A. , & Tobey, R. (2016). The first social ACO: Lessons learned from Commonwealth Care Alliance. Boston, MA: JSI Research & Training Institute; Retrieved from https://www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?xml:id=16450&lxml:id=3. [Google Scholar]

- Mervyn, K. , Amoo, N. , & Malby, R. (2019). Challenges and insights in inter‐organizational collaborative healthcare networks: An empirical case study of a place‐based network. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 27, 875–902. 10.1108/IJOA-05-2018-1415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B. , Huberman, A. M. , & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis (3rd ed .). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, J. , Ong, M. K. , Jones, L. , Chung, B. , Dixon, E. L. , Tang, L. , … Wells, K. B. (2013). Community‐partnered evaluation of depression services for clients of community‐based agencies in under‐resourced communities in LA. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 1279–1287. 10.1007/s11606-013-2480-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . (2019). Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Q. (2011). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Plsek, P. E. , & Greenhalgh, T. (2001). The challenge of complexity in health care. British Medical Journal, 323, 625–628. 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predmore, Z. , Hatef, E. , & Weiner, J. P. (2019). Integrating social and behavioral determinants of health into population health analytics: A conceptual framework and suggested road map. Population Health Management, 22, 488–494. 10.1089/pop.2018.0151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radermacher, H. , Karunarathna, Y. , Grace, N. , & Feldman, S. (2011). Partner or perish? Exploring inter‐organisational partnerships in the multicultural community aged care sector. Health and Social Care in the Community, 19, 550–560. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romm, I. , & Ajayi, T. (2017). “Weaving whole‐person health throughout an accountable care framework: The social ACO”, Health Affairs Blog, January 25. 10.1377/hblog20170125. 058419. [DOI]

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed .). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- San Martín‐Rodríguez, L. , Beaulieu, M. , D’Amour, D. , & Ferrada‐Videla, M. (2005). The determinants of successful collaboration: A review of theoretical and empirical studies. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19, 132–147. 10.1080/13561820500082677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unützer, J. , Katon, W. , Callahan, C. M. , Williams, J. W. Jr , Hunkeler, E. , Harpole, L. , … Langston, C. ; IMPACT Investigators. Improving Mood‐Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment . (2002). Collaborative care management of late‐life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 288, 2836–2845. 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N. , Duran, B. , Oetzel, J. G. , & Minkler, M. (2018). Community‐based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed .). San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe, C. , Caress, A. , Chew‐Graham, C. , & Todd, C. (2007). Evaluating partnership working: Lessons from palliative care. European Journal of Cancer Care, 16, 48–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, J. , Everingham, J. , Cuthill, M. , & Bartlett, H. (2008). Achieving effective collaborations to help communities age well. The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 67, 470–482. 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2008.00603.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. , & Alexander, J. (1998). The challenges of governing public‐private community health partnerships. Health Care Management Review, 23, 39–55. 10.1097/00004010-199804000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, E. S. , Anderson, R. M. , & Lasker, R. D. (2002). Making the most of collaboration: Exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Education & Behavior, 29(6), 683–698. 10.1177/109019802237938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F. , Zimmerman, B. , & Patton, M. Q. (2006). Getting to maybe: How the world is changed. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Random House Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B. , & Hummelbrunner, R. (2010). Systems concepts in action: A practitioner's toolkit. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B. , & van't Hof, S. (2016). Wicked solutions: A systems approach to complex problems (2nd ed.). Lulu. com.

- Zimmerman, B. , Lindberg, C. , & Plsek, P. (1998). Edgeware: Lessons from complexity science for health care leaders. Dallas, TX: VHA Inc. [Google Scholar]