Abstract

Background

The glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonist liraglutide may be beneficial in the regression of diabetic cardiomyopathy. South Asian ethnic groups in particular are at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Purpose

To assess the effects of liraglutide on left ventricular (LV) diastolic and systolic function in South Asian type 2 diabetes patients.

Study Type

Prospective, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial.

Population

Forty‐seven type 2 diabetes patients of South Asian ancestry living in the Netherlands, with or without ischemic heart disease, who were randomly assigned to 26‐week treatment with liraglutide (1.8 mg/day) or placebo.

Field Strength/Sequence

3T (balanced steady‐state free precession cine MRI, 2D and 4D velocity‐encoded MRI, 1H‐MRS, T1 mapping).

Assessment

Primary endpoints were changes in LV diastolic function (early deceleration peak [Edec], ratio of early and late peak filling rate [E/A], estimated LV filling pressure [E/Ea]) and LV systolic function (ejection fraction). Secondary endpoints were changes in aortic stiffness (aortic pulse wave velocity [PWV]), myocardial steatosis (myocardial triglyceride content), and diffuse fibrosis (extracellular volume [ECV]).

Statistical Tests

Data were analyzed according to intention‐to‐treat. Between‐group differences were reported as mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) and were assessed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

Results

Liraglutide (n = 22) compared with placebo (n = 25) did not change Edec (+0.2 mL/s2 × 10‐3 (–0.3;0.6)), E/A (–0.09 (–0.23;0.05)), E/Ea (+0.1 (–1.2;1.3)) and ejection fraction (0% (–3;2)), but decreased stroke volume (–9 mL (–14;–5)) and increased heart rate (+10 bpm (4;15)). Aortic PWV (+0.5 m/s (–0.6;1.6)), myocardial triglyceride content (+0.21% (–0.09;0.51)), and ECV (–0.2% (–1.4;1.0)) were unaltered.

Data Conclusion

Liraglutide did not affect LV diastolic and systolic function, aortic stiffness, myocardial triglyceride content, or extracellular volume in Dutch South Asian type 2 diabetes patients with or without coronary artery disease.

Level of Evidence: 1

Technical Efficacy Stage: 4

J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020;51:1679–1688.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, type 2; glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor; liraglutide; ventricular function, left; diabetic cardiomyopathies

TYPE 2 DIABETES is associated with a 2–5‐fold increased risk of heart failure.1 Diabetic cardiomyopathy, which is characterized by left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction, may eventually progress to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.1 A potential antihyperglycemic agent with cardioprotective effects is the glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonist liraglutide.2

Recently, the LEADER trial demonstrated a reduced total cardiovascular mortality as a result of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk, presumably because of a lower risk of ischemic events.3 Similar reductions in cardiovascular mortality have been reported in response to treatment with the GLP‐1 receptor agonists semaglutide and dulaglutide.4 However, it is largely unknown whether liraglutide in the management of type 2 diabetes is advantageous for heart function in asymptomatic diastolic dysfunction.2 It is conceivable that the favorable metabolic impact of liraglutide on lipid profiles and inflammatory markers,5 in addition to the natriuretic and vasodilatory actions,6, 7 has indirect beneficial effects on diastolic function. Liraglutide has been assumed to exert direct actions on the myocardium that may amend myocardial metabolism, although preclinical and clinical studies have not been conclusive.2 The effects of liraglutide on diastolic function may be mediated by regression of type 2 diabetes‐related myocardial steatosis, diffuse fibrosis, and aortic stiffening.1, 8 Notably, clinical studies have consistently reported an increase in heart rate in individuals using liraglutide.2, 5, 9 In this regard, the actual effect of liraglutide on heart function, taking into account the wide range of cardiovascular actions, is uncertain.

South Asian ethnic groups in particular are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.10 South Asians appear to have a strong genetic predisposition for insulin resistance, while differences in lifestyle factors seem to have a smaller role in the increased risk of type 2 diabetes as compared with other ethnic groups.11 The impaired insulin sensitivity in South Asians has been related to the relatively high total body fat percentage and high fat storage in the visceral compartments.12 In addition, adipocytes may be dysfunctional, as reflected by the increased release of free fatty acids, adipokines, and proinflammatory cytokines among South Asian individuals.13, 14 Previously, it has been demonstrated that hyperglycemia is more detrimental for cardiac function in South Asians than in Europeans.15 As the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, but also the impact of type 2 diabetes on cardiac function appears to be different, the cardiometabolic effects of liraglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes may be more pronounced in South Asians compared with individuals of other ethnicities.

In this study we aimed to assess the effects of 26‐week liraglutide treatment among South Asian type 2 diabetes patients on LV diastolic and systolic function and, secondary, myocardial steatosis and diffuse fibrosis. We used cardiovascular magnetic resonance, as this imaging modality enables the measurement of LV diastolic and systolic function and aortic stiffness16, 17 and also the assessment of myocardial tissue characteristics.18, 19

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study was a 26‐week double‐blind, randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02660047).20 Written informed consent was obtained prior to inclusion. The study complied with the revised Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects.

Patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the Leiden University Medical Centre (Leiden, the Netherlands), local hospitals, and general practices in Leiden and The Hague, and by advertisements in local newspapers. Individuals aged 18–75 years of South Asian ancestral origin with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin, sulfonylurea derivatives, and/or insulin for at least 3 months in stable dose were eligible for participation. South Asian descent was defined as both biological parents and their ancestors being South Asian (ie, South Asian Surinamese, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or Sri Lankan origin). Inclusion criteria were: body mass index (BMI) ≥23 kg/m2; HbA1c ≥6.5 and <11.0% (≥47.5 and <96.5 mmol/mol); estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >30 mL/min/1.73 m2; blood pressure <180/110 mmHg. Main exclusion criteria were: use of GLP‐1 receptor agonists; dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors, or thiazolidinediones within the past 6 months; heart failure, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III‐IV; acute coronary or cerebrovascular accident in the preceding 30 days; pancreatitis or medullary thyroid carcinoma; gastric bypass surgery; pregnant or lactating women; any contraindication for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Due to the insufficient number of eligible patients, several criteria were adjusted (initial inclusion criteria: age 18–70 years; HbA1c ≥7.0 and <10.0% (≥53 and <86 mmol/mol); eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2; blood pressure <150/85 mmHg; no history of cardiovascular disease).

Randomization, Blinding, and Intervention

Patients were randomized to once‐daily subcutaneous injections of liraglutide (Victoza, Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) or placebo added to standard care during 26 weeks (randomization with block size 4, with 1:1 stratification for sex and insulin use). A randomization code list was generated by the institutional research pharmacist. If necessary to prevent hypoglycemia, the concomitant glucose‐lowering medication was adjusted at study entry. Starting dose of the trial medication was 0.6 mg/day, which was increased every 7 days up to 1.8 mg/day. The dose was reduced upon poor tolerance. Investigators and patients were blinded to treatment allocation. Furthermore, the MRI data were stripped of any information on the participant's identity and measurement date.

Study Procedures

Study days at baseline and after 26 weeks consisted of clinical measurements and MRI. Baseline and follow‐up measurements were both scheduled either in the morning or evening. Patients were asked to fast overnight or for 6 hours, when measurements were in the morning or evening, respectively. To prevent hypoglycemia during fasting, the insulin dose was adjusted and other antidiabetic medications were temporarily discontinued. Patients were instructed to adhere to their usual diet and physical activity. During the trial, patients received a weekly telephone call for glycemic control based on their self‐monitored blood glucose levels. At week 4 and 12, routine blood tests and clinical measurements were performed. Glycemic control and blood pressure management was according to the current guidelines.21, 22 Patients were asked for adverse events once a week. Study drug pens were collected during the trial as a surrogate marker of compliance.

MRI Protocol

MRI scans were acquired with a 3T MR scanner (Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands). For contrast‐enhanced MRI, 0.15 mmol gadoterate meglumine (0.5 mmol/mL Dotarem; Guerbet, Villepinte, France) per kilogram of body weight was administered intravenously. LV systolic and diastolic function parameters were assessed by short‐axis and 4‐chamber cine balanced steady‐state free precession (bSSFP) and whole‐heart gradient‐echo 4D velocity‐encoded MRI, with retrospective ECG (electrocardiography) gating. To determine aortic stiffness, the aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV) was calculated from a scout view of the aorta and two 2D velocity‐encoded scans at the ascending and abdominal aorta. Myocardial steatosis was quantified as the myocardial triglyceride content, examined by proton‐magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H‐MRS) in the mid‐ventricular septum and expressed as the amplitude of triglyceride methylene divided by the amplitude of unsuppressed water, multiplied by 100%. Myocardial diffuse fibrosis was assessed using native and postcontrast modified Look–Locker inversion (MOLLI) recovery T1 mapping. Native T1 and the extracellular volume (ECV) were measured in the mid‐ventricular septum. To identify ischemic scarring, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) MRI was acquired. If septal delayed enhancement was present, myocardial triglyceride content data were excluded and diffuse fibrosis was measured outside the region with scar. LGE‐MRI was assessed visually by a radiologist (H.J.L.) and clinical investigator (E.H.M.P.) with 25 and 4 years of experience in cardiovascular MRI, respectively. A detailed description of the MRI protocol is provided as Supplementary Material.

Study Endpoints

Primary endpoints were LV diastolic function (peak deceleration slope of the transmitral early peak filling rate [Edec], ratio of transmitral early and late peak filling rate [E/A], early peak diastolic mitral septal tissue velocity [Ea], estimated LV filling pressure [E/Ea]) and LV systolic function (ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output, cardiac index, peak ejection rate). Secondary endpoints included myocardial triglyceride content, ECV, aortic PWV, LV dimensions, and clinical parameters (heart rate, blood pressure, body weight, and HbA1c).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v. 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY), according to intention‐to‐treat. Within‐group differences from baseline to 26 weeks are reported as means ± SD. Between‐group differences for liraglutide vs. placebo were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the baseline values as covariate to reduce within‐ and between‐group variability and are reported as means (95% CI). Statistical tests were 2‐sided and P < 0.05 was considered significant. The power calculation is described in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

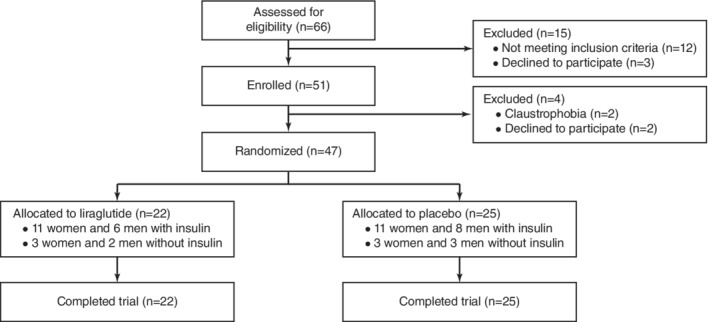

Patients were recruited between July 16, 2015, and December 6, 2017. A total of 47 patients were randomized to liraglutide (n = 22) or placebo (n = 25) (Fig. 1). Between October 7, 2015, and March 9, 2018, all participants completed the trial. There were no clinically relevant differences between the treatment groups regarding demographics and clinical, laboratory, and MRI parameters (Table 1). The total study population (40% men) had a mean (SD) age of 55 ± 10 years, a diabetes duration of 18 ± 10 years, and HbA1c of 8.4 ± 1.0% (68 ± 11 mmol/mol), while 77% of the patients were using insulin.

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Liraglutide (n = 22) | Placebo (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ||

| Age, years | 55 (11) | 55 (9) |

| Men, no. | 8 (36%) | 11 (44%) |

| Diabetes duration, years | 19 (10) | 17 (10) |

| Diabetes complications, no. | 15 (68%) | 16 (64%) |

| Coronary artery disease, no. | ||

| Nonsignificant coronary artery stenosis | 4 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 2 (9%) | 3 (12%) |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 1 (5%) | 2 (8%) |

| Smoking, no. | ||

| Currently | 2 (9%) | 5 (20%) |

| Previously | 6 (27%) | 0 (0%) |

| Never | 14 (64%) | 20 (80%) |

| Medication | ||

| Metformin, no. | 22 (100%) | 23 (92%) |

| Sulfonylurea derivatives, no. | 3 (14%) | 5 (20%) |

| Insulin, no. | 17 (77%) | 19 (76%) |

| Metformin dose, g/day | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) |

| Insulin dose, units/day | 77 (34) | 67 (30) |

| Lipid‐lowering drugs, no. | 17 (77%) | 20 (80%) |

| Antihypertensive drugs, no. | 16 (73%) | 18 (72%) |

| Beta‐blockers, no. | 8 (36%) | 9 (36%) |

| Diuretics, no. | 9 (41%) | 8 (32%) |

| ACE‐inhibitors, no. | 6 (27%) | 7 (28%) |

| Angiotensin II receptor‐blockers, no. | 7 (32%) | 9 (36%) |

| Calcium‐antagonists, no. | 2 (9%) | 5 (20%) |

| Clinical parameters | ||

| Weight, kg | 82 (11) | 78 (12) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.4 (3.8) | 28.6 (4.0) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 104 (8) | 98 (10) |

| Waist‐hip ratio | 1.00 (0.07) | 0.95 (0.09) |

| Heart rate, bpm | 73 (13) | 77 (11) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 149 (25) | 141 (18) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 85 (11) | 85 (10) |

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| HbA1c, % | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.6 (1.1) |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 65 (10) | 70 (12) |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.6 (0.9) | 2.1 (1.8) |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.5 (1.1) |

| HDL‐cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.3) |

| LDL‐cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.2 (1.0) |

| LV diastolic function | ||

| Edec, mL/s2 x10‐3 | –2.5 (1.3) | –2.7 (1.2) |

| E, mL/s | 305 (99) | 328 (118) |

| A, mL/s | 316 (75) | 306 (58) |

| E/A | 0.99 (0.31) | 1.11 (0.43) |

| E, cm/s | 34 (9) | 37 (9) |

| Ea, cm/s | 5.3 (2.1) | 5.7 (1.9) |

| E/Ea | 7.4 (3.9) | 7.4 (3.3) |

| LV systolic function | ||

| Stroke volume, mL | 70 (12) | 67 (15) |

| Ejection fraction, % | 56 (8) | 57 (7) |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 4.7 (0.9) | 4.7 (1.1) |

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2 | 2.4 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.4) |

| Peak ejection rate, mL/s | 338 (82) | 345 (84) |

| LV structure | ||

| End‐diastolic volume, mL | 128 (25) | 120 (36) |

| End‐systolic volume, mL | 57 (21) | 53 (24) |

| Mass, g | 98 (22) | 96 (24) |

| Aortic stiffness | ||

| Aortic pulse wave velocity, m/s | 8.8 (2.4) | 8.3 (2.4) |

| Myocardial tissue characteristics | ||

| Myocardial triglyceride content, % | 0.92 (0.43) | 1.00 (0.58) |

| Native T1 relaxation time, msec | 1264 (45) | 1254 (33) |

| Extracellular volume, % | 25.9 (3.1) | 27.0 (2.6) |

Data are presented as mean (SD) or number (%). Diabetes complications: retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy or macrovascular complications. A: late transmitral peak filling rate; E: early transmitral peak filling rate; Ea: early peak diastolic mitral septal tissue velocity; E/Ea: estimation of LV filling pressure; Edec: early deceleration peak.

Drug Compliance and Clinical Parameters

Study drug compliance was high (95 ± 8% and 99 ± 5% for liraglutide and placebo treatment, respectively) and the dose could be titrated up to 1.8 mg/day in most patients (in 86% and 96% of the patients treated with liraglutide and placebo, respectively). For glycemic control, in some patients in the placebo group concomitant medication was started (metformin [n = 1] or sulfonylurea derivates [n = 3]) or the insulin dose was adjusted (1 ± 23 and –11 ± 34 units/day in the placebo and liraglutide group, respectively). For blood pressure management, in some patients in the placebo and liraglutide group antihypertensive mediation was started or the dose was elevated (n = 5 vs. n = 3) or the dose was reduced (n = 1 vs. n = 2).

In both the liraglutide and placebo group there was a decrease (mean ± SD) after 26 weeks in HbA1c (–0.8 ± 1.0 vs. –0.6 ± 0.8%; –9 ± 11 vs. –7 ± 9 mmol/mol) and systolic blood pressure (–14 ± 18 vs. –7 ± 15 mmHg), but not in diastolic blood pressure (–3 ± 11 vs. –3 ± 9 mmHg). However, between‐group differences for liraglutide vs. placebo in HbA1c (–0.4% [95% CI: –0.9 to 0.2]; –4 mmol/mol [95% CI: –10 to 2], P = 0.16) and systolic blood pressure (–3 mmHg [95% CI: –9 to 3, P = 0.36]) were nonsignificant. Liraglutide compared with placebo decreased body weight (–3.9 ± 3.6 vs. –0.6 ± 2.2 kg; between‐group difference: –3.5 kg [95% CI: –5.3 to –1.8, P < 0.001]) and increased heart rate (9 ± 11 vs. –2 ± 8 bpm; between‐group difference: 10 bpm [95% CI: 4 to 15, P = 0.001]).

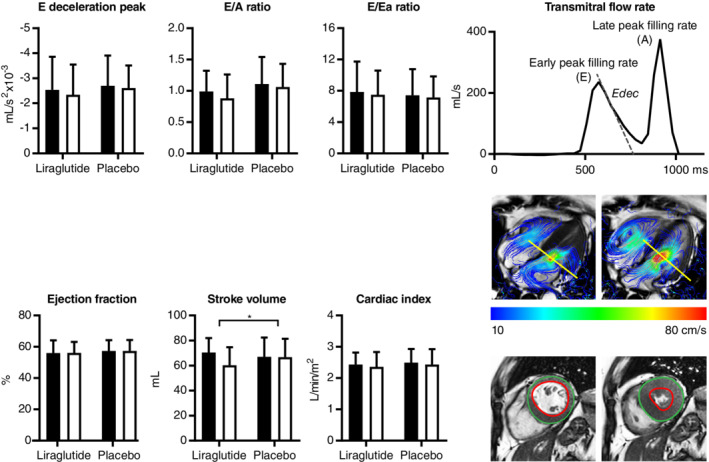

LV Function, Aortic Stiffness, and Myocardial Tissue Characteristics

LV diastolic function parameters were unaltered by liraglutide. Also, LV systolic function was unaffected upon liraglutide, as the ejection fraction and peak ejection rate were unchanged and, despite the decreased stroke volume, cardiac output and cardiac index were preserved (Table 2, Fig. 2). The decrease in stroke volume was in parallel with the reductions in end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volume, which persisted when adjusting for body surface area. Whereas liraglutide significantly reduced end‐diastolic volume, the decrease in LV mass was not significant. Also, liraglutide did not change aortic stiffness, myocardial triglyceride content, or diffuse fibrosis. A total of six patients had delayed enhancement at baseline, but in only one patient was the ventricular septum involved. In all patients, the extent of delayed enhancement was unchanged at follow‐up. Details on missing values are provided as Supplementary Material.

Table 2.

Study Endpoints: Mean Change Over 26 Weeks

| Mean change (SD) from 0 to 26 weeks | Mean change (95% CI) from 0 to 26 weeks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liraglutide (n = 22) | Placebo (n = 25) | (Liraglutide vs. Placebo) | P value | |

| Primary | ||||

| LV diastolic function | ||||

| Edec, mL/s2 x10‐3 | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.2 (–0.3 to 0.6) | 0.46 |

| E, mL/s | –36 (84) | –18 (55) | –24 (–60 to 12) | 0.18 |

| A, mL/s | 17 (77) | –2 (45) | 18 (–21 to 56) | 0.35 |

| E/A | –0.11 (0.24) | –0.05 (0.24) | –0.09 (–0.23 to 0.05) | 0.21 |

| E, cm/s | –2 (7) | –1 (7) | –2 (–6 to 1) | 0.20 |

| Ea, cm/s | –0.1 (1.1) | –0.1 (1.1) | –0.1 (–0.7 to 0.5) | 0.73 |

| E/Ea | –0.4 (2.4) | –0.3 (2.6) | 0.1 (–1.2 to 1.3) | 0.89 |

| LV systolic function | ||||

| Ejection fraction, % | 0 (5) | 0 (3) | 0 (–3 to 2) | 0.86 |

| Stroke volume, mL | –10 (9) | 0 (7) | –9 (–14 to –5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | –0.2 (0.5) | –0.1 (0.5) | –0.1 (–0.4 to 0.2) | 0.44 |

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2 | –0.1 (0.3) | –0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 (–0.2 to 0.1) | 0.87 |

| Peak ejection rate, mL/s | –9 (60) | –7 (45) | –3 (–34 to 27) | 0.83 |

| Secondary | ||||

| LV structure | ||||

| Mass, g | –4 (9) | 0 (7) | –4 (–9 to 0) | 0.07 |

| End‐diastolic volume, mL | –19 (13) | –1 (11) | –17 (–24 to –10) | <0.001 |

| End‐systolic volume, mL | –9 (9) | –1 (7) | –7 (–11 to –3) | 0.001 |

| Aortic stiffness | ||||

| Aortic pulse wave velocity, m/s | 0.2 (2.1) | –0.2 (1.7) | 0.5 (–0.6 to 1.6) | 0.35 |

| Myocardial tissue characteristics | ||||

| Myocardial triglyceride content, % | 0.14 (0.47) | –0.09 (0.56) | 0.21 (–0.09 to 0.51) | 0.16 |

| Native T1 relaxation time, msec | –6 (36) | 6 (26) | –7 (–21 to 7) | 0.35 |

| Extracellular volume, % | 0.5 (2.6) | 0.4 (1.3) | –0.2 (–1.4 to 1.0) | 0.76 |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Liraglutide does not alter left ventricular (LV) diastolic and systolic function in South Asian type 2 diabetes patients with or without coronary artery disease and without advanced heart failure. LV diastolic and systolic outcome measures (mean ± SD) before (black bars) and after (white bars) treatment with liraglutide and placebo are presented. An example of a transmitral flow rate curve, 4D velocity‐encoded, and short‐axis cine magnetic resonance image is provided for illustration. E/A: ratio of transmitral early and late peak filling rate; E/Ea: estimation of LV filling pressure; Ea: early peak diastolic mitral septal tissue velocity; Edec: early deceleration peak.

Adverse Events

There was one serious adverse event in the placebo group (admission for acute coronary syndrome symptoms without requiring further treatment). More patients with treatment with liraglutide compared with placebo had complaints of nausea (73% vs. 40%) and vomiting (27% vs. 8%). There were no cases of severe hypoglycemia.

Discussion

In this double‐blind, randomized controlled trial in type 2 diabetes patients of South Asian descent living in the Netherlands, with or without coronary artery disease, 26‐week treatment with 1.8 mg/day liraglutide had no effect on LV diastolic and systolic function, aortic stiffness, myocardial triglyceride content, or extracellular volume as compared with placebo when added to standard care. Our results imply that liraglutide does not amend cardiovascular remodeling in diabetic cardiomyopathy in a Dutch South Asian type 2 diabetes population including patients with preexisting ischemic heart disease, at least not upon a treatment period of 26 weeks.

Mechanisms

Whether liraglutide exerts direct actions on the ventricles, such as enhancement of coronary blood flow and myocardial glucose uptake, has been debated.2 The GLP‐1 receptor has been demonstrated to be present on the sinoatrial node and atrial cardiomyocytes,23 but its function as well as its presence on ventricular cardiomyocytes and blood vessels in humans is still uncertain. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the cardioprotective effects of native GLP‐1 as described in earlier studies may be related to actions of degradation products of GLP‐1, which are not produced by GLP‐1 analogs.2 We hypothesized that liraglutide may reverse diabetic cardiomyopathy, partly as a result of its indirect cardiovascular actions.5, 6, 7 However, based on our findings, at least large immediate effects on LV function in South Asian type 2 diabetes patients can be excluded.

The reductions in LV end‐diastolic volume and stroke volume in our study were not explained by liraglutide‐induced body weight loss. It is conceivable that the decreased end‐diastolic volume and stroke volume were related to the increased heart rate and consequent reduced ventricular filling time. Notably, the elevation in heart rate in our study was relatively large compared with other trials with the same dose and of similar duration.2, 5, 9 Proposed mechanisms for the heart rate acceleration upon treatment with GLP‐1 receptor agonists include enhancement of the sympathetic activity24 and inhibition of the cardiac vagal neurons25 as well as direct sinoatrial node stimulation.9 Our study population included patients with prevalent coronary artery disease. It has been suggested that individuals with preexisting cardiac disease may be more susceptible to heart rate acceleration upon GLP‐1 receptor agonists.2 Furthermore, South Asians may have an altered balance in the autonomic nervous system,26 which may have contributed to the profound heart rate elevation by liraglutide treatment in our study population.

Previous Studies

Only a few previous studies, including two open‐label randomized controlled trials27, 28 and one small double‐blind randomized controlled trial,29 assessed the effect of liraglutide on diastolic function in type 2 diabetes, during an intervention period of 4–6 months. One study demonstrated an improvement in myocardial relaxation in response to liraglutide, with amelioration of aortic stiffening,28 whereas others reported no improvement of diastolic function.27, 29 Large trials on the impact of liraglutide on systolic function have been previously performed in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, where no effect was reported.30, 31 Regarding the impact of GLP‐1 receptor agonists on myocardial tissue characteristics, most research has been limited to preclinical studies. In animal models of type 2 diabetes, liraglutide has been shown to reduce cardiac fibrosis,32 possibly by inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway via activation of the AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) system.33, 34 Activation of AMPK, which acts as a regulator of cellular energy status, has also been proposed as the underlying mechanism for improved cardiac function in type 2 diabetes after liraglutide, as observed in preclinical research.33 Furthermore, GLP‐1 receptor agonists have been shown to relieve the intramyocardial lipid deposition in diabetic mice, in association with ameliorated levels of plasma cholesterol.35 However, attenuation of myocardial steatosis by treatment with GLP‐1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes has not been confirmed in human studies.36

In a recent double‐blind randomized controlled trial on the effect of liraglutide on cardiac function in European type 2 diabetes patients,37 liraglutide decreased the LV filling pressure, presumably through natriuresis and vasorelaxation, whereas myocardial relaxation was unaltered. Apart from ethnicity, the present South Asian cohort was distinct from this European study group regarding sex (40% vs. 59% men), diabetes duration (18 ± 10 vs. 11 ± 7 years), insulin use (77% vs. 65%), and ischemic heart disease (17% vs. 0%). As there have been no large‐scale clinical studies, it remains unknown whether certain patient characteristics have a modifying role in the cardiovascular actions of liraglutide.

Strengths and Limitations

The most important strengths of the present study are related to its double‐blind, randomized controlled design, the absence of dropouts, and high study drug compliance. Liraglutide was added to standard care, mimicking the real‐world setting. There are some limitations that need to be addressed. This trial comprised South Asian individuals living in a high‐income country and included predominantly South Asian Surinamese, who originate from the northern part of India. Extrapolation of our results to other South Asian ethnic groups should be performed with caution. Furthermore, we did not use echocardiography, which is the routine clinical approach for evaluating diastolic function. Nonetheless, MRI is widely used in clinical studies for the assessment of diastolic function and, importantly, it has been validated with echocardiography.38 It has to be noted that in individuals with high heart rate (>100 bpm), early and late diastolic filling cannot be separated. As a consequence, two participants in the liraglutide group had missing data for diastolic function at follow‐up, which might have introduced bias. The LV diastolic function parameters in our study population, as well as aortic pulse wave velocity, were approximately one standard deviation from the mean in healthy individuals.39 However, in contrast to the clear impairments in LV diastolic function, the myocardial triglyceride content was 0.92–1.00% in this type 2 diabetes cohort, whereas the values in healthy controls are ~0.58% and 0.84% among Europeans and South Asians, respectively.39 The type 2 diabetes patients in the present study did not demonstrate abnormalities in myocardial extracellular volume, possibly as a result of angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which may relieve fibrotic remodeling.39 Hence, we cannot exclude a beneficial effect of liraglutide on extracellular volume in type 2 diabetes patients with marked cardiac fibrosis. Also, we cannot preclude cardiovascular benefits after prolonged (>26 weeks) therapy with liraglutide. Nevertheless, in animal studies, improved myocardial function has been reported already after brief (1 week) treatment with liraglutide.33

Implications

In our study, liraglutide did not enhance heart function and may therefore have no specific role in the prevention of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in South Asian type 2 diabetes patients. In contrast, recent studies have indicated that the sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and dapagliflozin have a benefit on the incidence of heart failure,4 potentially because of direct improvement of myocardial relaxation in addition to diuretic effects.40 Conversely, the previously reported reduced cardiovascular mortality rate in response to liraglutide among patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk is probably primarily related to slowed progression of atherosclerosis.3, 41 Following the results from recent cardiovascular outcome trials,3, 4 SGLT2 inhibitors have been recommended as part of type 2 diabetes management among individuals with coexisting heart failure or at risk of heart failure, and either GLP‐1 receptor agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors should be considered in type 2 diabetes patients with established atherosclerotic disease and no specific concerns of heart failure.22 Our study did not demonstrate regression of LV diastolic dysfunction in response to liraglutide. Nonetheless, because of its presumed antiatherosclerotic actions, GLP‐1 receptor agonists remain worth considering, especially in South Asian type 2 diabetes patients, given their disadvantageous cardiometabolic profile and high risk of ischemic heart disease.10

In conclusion, in this 26‐week double‐blind randomized placebo‐controlled trial in Dutch South Asian type 2 diabetes patients with or without coronary artery disease, liraglutide had no effect on LV diastolic and systolic function, nor on aortic stiffness, myocardial triglyceride content, or extracellular volume. A previous study reported a reduced LV filling pressure after liraglutide therapy in a European cohort of type 2 diabetes patients without ischemic heart disease, who were predominantly men, with a shorter diabetes duration, and less use of insulin as compared with the South Asian type 2 diabetes patients in the present study.37 Further research should reveal whether the cardiovascular impact of liraglutide might be dependent on patient characteristics such as sex, ethnicity, diabetes duration, comedication, or history of ischemic heart disease.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting information

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating patients. We thank all physicians and nurses from Haaglanden Medical Centre (The Hague, the Netherlands) for inviting eligible patients, and P.J. van den Boogaard for support in MRI acquisition and B. Ladan‐Eygenraam for assistance in the clinical data collection.

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

Contract grant sponsor: Cardio Vascular Imaging Group (CVIG), Leiden University Medical Centre (Leiden, the Netherlands); Contract grant sponsor: Roba Metals B.V. IJsselstein (Utrecht, the Netherlands); Contract grant sponsor: Novo Nordisk A/S (Bagsvaerd, Denmark), which also provided the trial medication. Novo Nordisk had no role in the trial design, data collection, or analysis or reporting of the results.

References

- 1. Marwick TH, Ritchie R, Shaw JE, Kaye D. Implications of underlying mechanisms for the recognition and management of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drucker DJ. The cardiovascular biology of glucagon‐like peptide‐1. Cell Metab 2016;24:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown‐Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016;375:311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. Comparison of the effects of glucagon‐like peptide receptor agonists and sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for prevention of major adverse cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2019;139:2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dalsgaard NB, Vilsboll T, Knop FK. Effects of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists on cardiovascular risk factors: A narrative review of head‐to‐head comparisons. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20:508–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lovshin JA, Barnie A, DeAlmeida A, Logan A, Zinman B, Drucker DJ. Liraglutide promotes natriuresis but does not increase circulating levels of atrial natriuretic peptide in hypertensive subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koska J, Sands M, Burciu C, et al. Exenatide protects against glucose‐ and lipid‐induced endothelial dysfunction: evidence for direct vasodilation effect of GLP‐1 receptor agonists in humans. Diabetes 2015;64:2624–2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gulsin GS, Swarbrick DJ, Hunt WH, et al. Relation of aortic stiffness to left ventricular remodeling in younger adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2018;67:1395–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakatani Y, Kawabe A, Matsumura M, et al. Effects of GLP‐1 receptor agonists on heart rate and the autonomic nervous system using Holter electrocardiography and power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. Diabetes Care 2016;39:e22–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tillin T, Hughes AD, Mayet J, et al. The relationship between metabolic risk factors and incident cardiovascular disease in Europeans, South Asians, and African Caribbeans: SABRE (Southall and Brent Revisited) — A prospective population‐based study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1777–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bakker LE, Sleddering MA, Schoones JW, Meinders AE, Jazet IM. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes in South Asians. Eur J Endocrinol 2013;169:R99–R114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Banerji MA, Faridi N, Atluri R, Chaiken RL, Lebovitz HE. Body composition, visceral fat, leptin, and insulin resistance in Asian Indian men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abate N, Chandalia M, Snell PG, Grundy SM. Adipose tissue metabolites and insulin resistance in nondiabetic Asian Indian men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2750–2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forouhi NG, Sattar N, McKeigue PM. Relation of C‐reactive protein to body fat distribution and features of the metabolic syndrome in Europeans and South Asians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25:1327–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park CM, Tillin T, March K, et al. Hyperglycemia has a greater impact on left ventricle function in South Asians than in Europeans. Diabetes Care 2014;37:1124–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brandts A, Bertini M, van Dijk EJ, et al. Left ventricular diastolic function assessment from three‐dimensional three‐directional velocity‐encoded MRI with retrospective valve tracking. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011;33:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grotenhuis HB, Westenberg JJ, Steendijk P, et al. Validation and reproducibility of aortic pulse wave velocity as assessed with velocity‐encoded MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;30:521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Meer RW, Doornbos J, Kozerke S, et al. Metabolic imaging of myocardial triglyceride content: Reproducibility of 1H MR spectroscopy with respiratory navigator gating in volunteers. Radiology 2007;245:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diao KY, Yang ZG, Xu HY, et al. Histologic validation of myocardial fibrosis measured by T1 mapping: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2016;18:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Eyk HJ, Paiman EHM, Bizino MB, et al. A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomised trial to assess the effect of liraglutide on ectopic fat accumulation in South Asian type 2 diabetes patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2019;18:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. American Diabetes A . 6. Glycemic targets: Standards of medical care in diabetes–2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42(Suppl 1):S61–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Diabetes A . 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: Standards of medical care in diabetes–2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42(Suppl 1):S103–S123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baggio LL, Yusta B, Mulvihill EE, et al. GLP‐1 receptor expression within the human heart. Endocrinology 2018;159:1570–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamamoto H, Lee CE, Marcus JN, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor stimulation increases blood pressure and heart rate and activates autonomic regulatory neurons. J Clin Invest 2002;110:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Griffioen KJ, Wan R, Okun E, et al. GLP‐1 receptor stimulation depresses heart rate variability and inhibits neurotransmission to cardiac vagal neurons. Cardiovasc Res 2011;89:72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bathula R, Francis DP, Hughes A, Chaturvedi N. Ethnic differences in heart rate: Can these be explained by conventional cardiovascular risk factors? Clin Auton Res 2008;18:90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nystrom T, Padro Santos I, Hedberg F, et al. Effects on subclinical heart failure in type 2 diabetic subjects on liraglutide treatment vs. Glimepiride both in combination with metformin: A randomized open parallel‐group study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lambadiari V, Pavlidis G, Kousathana F, et al. Effects of 6‐month treatment with the glucagon like peptide‐1 analogue liraglutide on arterial stiffness, left ventricular myocardial deformation and oxidative stress in subjects with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018;17:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jorgensen PG, Jensen MT, Mensberg P, et al. Effect of exercise combined with glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist treatment on cardiac function: A randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:1040–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jorsal A, Kistorp C, Holmager P, et al. Effect of liraglutide, a glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue, on left ventricular function in stable chronic heart failure patients with and without diabetes (LIVE)—A multicentre, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Margulies KB, Hernandez AF, Redfield MM, et al. Effects of liraglutide on clinical stability among patients with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:500–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhao T, Chen H, Xu F, et al. Liraglutide alleviates cardiac fibrosis through inhibiting P4halpha‐1 expression in STZ‐induced diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2019;51:293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Noyan‐Ashraf MH, Shikatani EA, Schuiki I, et al. A glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analog reverses the molecular pathology and cardiac dysfunction of a mouse model of obesity. Circulation 2013;127:74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ji Y, Zhao Z, Cai T, Yang P, Cheng M. Liraglutide alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy by blocking CHOP‐triggered apoptosis via the inhibition of the IRE‐alpha pathway. Mol Med Rep 2014;9:1254–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Monji A, Mitsui T, Bando YK, Aoyama M, Shigeta T, Murohara T. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor activation reverses cardiac remodeling via normalizing cardiac steatosis and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013;305:H295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dutour A, Abdesselam I, Ancel P, et al. Exenatide decreases liver fat content and epicardial adipose tissue in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes: A prospective randomized clinical trial using magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Diabetes Obes Metab 2016;18:882–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bizino MB, Jazet IM, Westenberg JJM, et al. Effect of liraglutide on cardiac function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Randomized placebo‐controlled trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2019;18:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buss SJ, Krautz B, Schnackenburg B, et al. Classification of diastolic function with phase‐contrast cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: Validation with echocardiography and age‐related reference values. Clin Res Cardiol 2014;103:441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paiman EHM, van Eyk HJ, Bizino MB, et al. Phenotyping diabetic cardiomyopathy in Europeans and South Asians. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2019;18:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pabel S, Wagner S, Bollenberg H, et al. Empagliflozin directly improves diastolic function in human heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:1690–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rakipovski G, Rolin B, Nohr J, et al. The GLP‐1 analogs liraglutide and semaglutide reduce atherosclerosis in ApoE(‐/‐) and LDLr(‐/‐) mice by a mechanism that includes inflammatory pathways. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2018;3:844–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting information